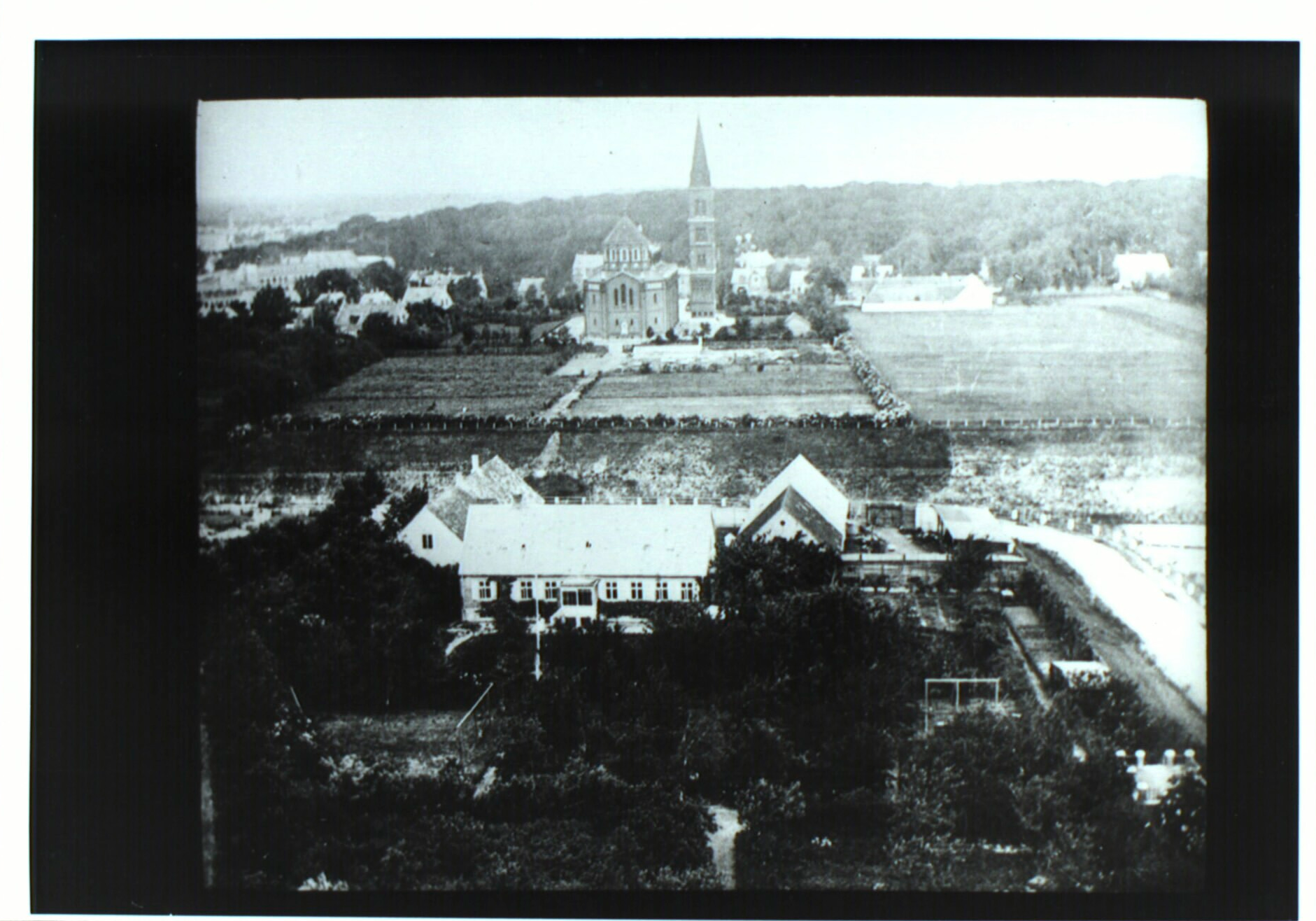

When your rival buys the half-built shell of the massive church across from the royal palace and promises, after 150 years, to finish it…well, if you’re Carl Jacobsen, the brewery tycoon behind Carlsberg, you try to one-up him by picking a site on Copenhagen’s biggest hill and building yourself a wonderfully bonkers church. Designed by Vilhelm Dahlerup, the opulent Jesuskirken might be the least Lutheran-looking church in Denmark. That’s because, well, it sort of is—Jacobsen and Dahlerup cribbed heavily from Catholic churches in Ravenna and Poitiers when designing Jesuskirken. From its conception in the late 1870s through construction in the 1880s and finally completion of the campanile in 1895, the project to build Jesuskirken swung wildly between profligacy and compromise to eventually make that grand vision a reality.

Both an everyday parish church for a working-class part of Copenhagen and a hubristic monument to one of the wealthiest families in Danish history, Jesuskirken is a riot, one of the most unusual churches in Denmark.

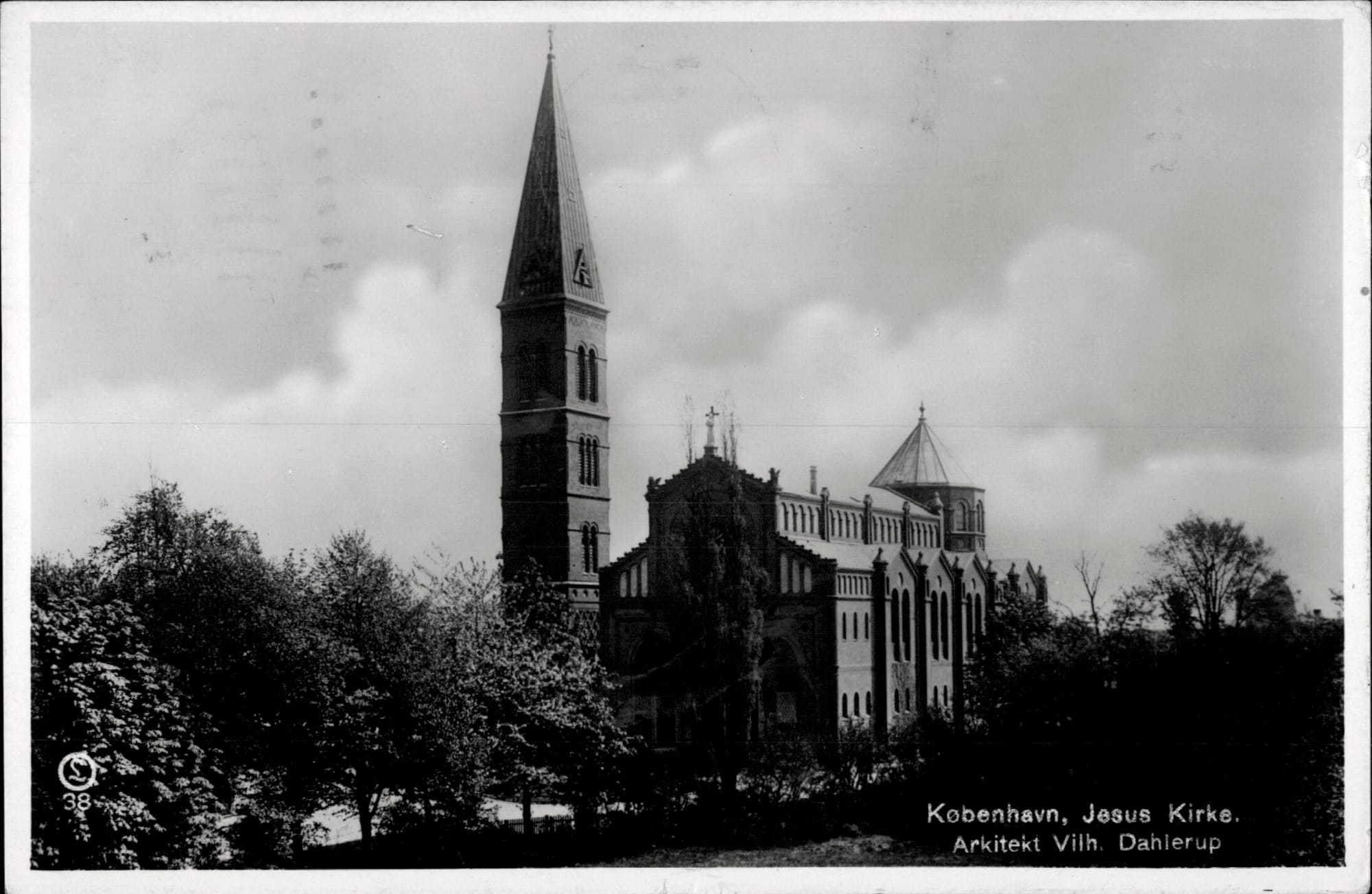

So, what’s changed? Foliage, street signs, street lamps, but virtually nothing substantial. Jesuskirken itself looks incredible. …Well shit, I could’ve tried to match the timing on the clock in the rose window.

J.C. Jacobsen founded Carlsberg in 1847 and named his brewery after his son, Carl, and the fact that it stood on a hill. J.C.’s passion was Danish history and the creation of a Danish nation, so he spent his wealth on the restoration of Frederiksborg Castle and the creation of the Museum of National History there. Carl became a brewer as well—he’d leave the family business after becoming estranged from his father and started a brewery of his own which he called, confusingly, New Carlsberg—but culture might’ve been his true passion. Carl Jacobsen and his wife Ottilia were major patrons of the arts in Copenhagen, later cajoling the government into building a museum, Glyptoteket, for their art and antiquities collection (and partially funding it). They even had a favorite architect, Vilhelm Dahlerup, who designed a bunch of buildings around the New Carlsberg brewery, Søpavillonen, and—at Jacobsen’s urging—Glyptoteket.

There was an even larger church building project going in Copenhagen in the 1870s and 1880s—after more than a century as a half-built ruin, construction had finally resumed on Frederiks Kirke, the massive domed church across from Amalienborg, the royal palace. It was one of the other richest men in Denmark, financier C.F. Tietgen, who led the completion of Frederiks Kirke (...Tietgen’s plan to finish Marmorkirken came in the form of a slightly questionable proto public-private partnership which lead to ministerial impeachments, but did eventually get the church finished). Carl Jacobsen wasn’t even particularly religious, but with a rival plutocrat honored with the opportunity to finish the royal family’s church, there’s a whiff of competitive response in Jacobsen’s late 1870s purchase of this land—highly visible on a hill, next to New Carlsberg brewery—with plans to build a church of his own.

Carl Jacobsen used his inheritance from J.C. to finance construction. He had received his inheritance early from his estranged father but—rich as hell already—didn’t really need it, so he endowed four foundation funds with it, including one to support the building of a church. Jesuskirken also foreshadowed the move Jacobsen would pull with Glyptoteket a bit later—graciously funding the construction of something the public (remember, Jesuskirken was part of the Danish State Church) would need to pay to maintain, while also demanding that the government cede aesthetic and (ideally) administrative control. To the extent he was religious, Carl Jacobsen was a member of the Danish State Church, but he admired Catholic aesthetics and was most interested in the story of Jesus as a man. An idiosyncratic combination.

Dahlerup sketch of Notre-Dame-la-Grande in Poitiers, Tidsskrift for kunstindustri | Early studies, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Sketch, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Sketch, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Campanile sketch, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Sketch from the side, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Cross-sections, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Floor plans, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Hack Kampman sketch, Det Kgl. Bibliotek

Jacobsen had strong ideas about what kind of church he wanted built, inspired by the Basilica of San Vitale and Notre-Dame-la-Grande in Poitiers (again, notice they’re Catholic churches), and hired his architect-of-choice to translate his ideas into something buildable. Trying to reconcile Jesuskirken as a monument to the Jacobsen family, as a functional parish church, and as implicit competition to Marmorkirken, the design process here swung from free-spending exuberance to thrifty retreat to luxurious compromise. You can see that dynamic in the brick and in the tower—initial plans specified munkesten, a bigger style of Danish brick from the Middle Ages, but pivoted to regular brick to cut costs, and the campanile wasn’t built at all first after the project greatly overran its budget.

Working closely with Jacobsen as well as Dahlerup studio architects including Osvald Rosendahl Langballe, Johan Wessel, Ludvig Bottger Rasmussen, and Axel Moller, the end result is a historicist church unlike any other in Denmark. Evoking early Italian and French basilicas, but with a Byzantine flair, Jesuskirken is wildly ornate for a Danish church—put glibly, a Lutheran church with Catholic aesthetics. That rose window with the brewer’s star (the Star of David is also the symbol of brewers) is the largest in Denmark, produced by August Duvier, the Danish answer to Louis Comfort Tiffany. While finishing up work on this one, Dahlerup would begin design work on Glyptoteket.

1889, construction update | 1891 dedication article | 1891 description article | Early 1890s photo, pre-campanile, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Sketch pre-campanile, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1894 article on the construction of the campanile

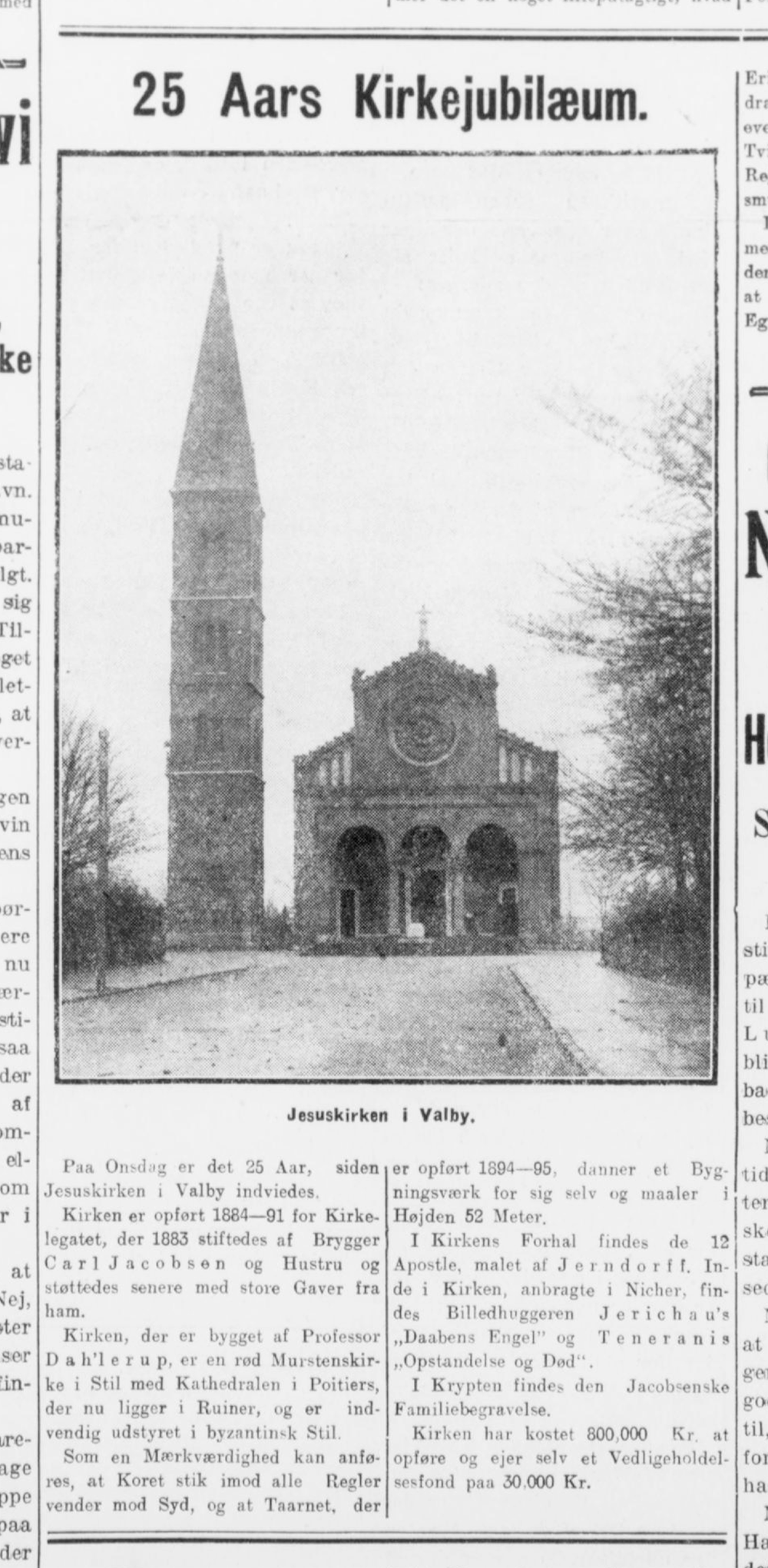

The cornerstone was laid in 1885, and Jesuskirken—finished without the tower—was dedicated in 1891. A testament to Jacobsen’s pull, the Crown Prince of Denmark, Minister of Culture, Minister of the Navy, and Minister of War all attended the dedication. With the campanile missing, the church was described as “incomplete” and “bald” when completed.

Jesuskirken would serve as the eternal resting place for the Jacobsen family—Carl had an ornate mausoleum for the family built in the crypt. Not content with the usual move of claiming the crypt of a parish church for a private family, Carl Jacobsen also wanted to exert his influence on Jesuskirken from the grave—he wanted the right to nominate the priest here, and he wanted that power to be a hereditary one passed down to Jacobsen family members. Again, there might’ve been some jealousy towards C.F. Tietgen here—he had the right to appoint the priests at Marmorkirken during the life of Christian IX. As far as I understand, the law couldn’t allow for that power to be passed down, but Jacobsen did pick Jesuskirken’s first priest, Henry Ussing (whose father happened to sit on the board of directors of the New Carlsberg Foundation).

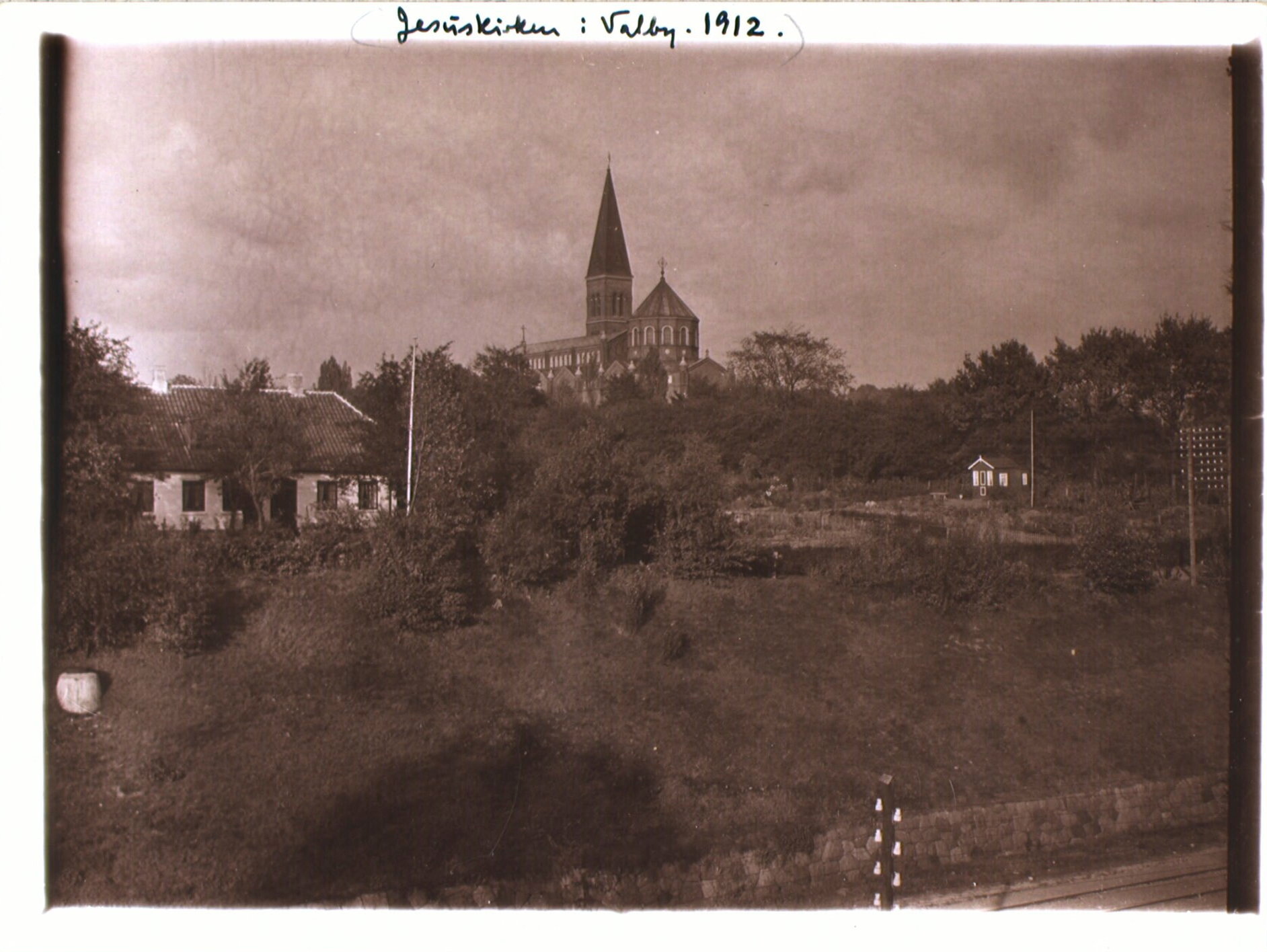

1895, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Undated, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1890s, Anders Vilhelm Christensen, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Undated, Lars Peter Elfelt, Det Kgl Bibliotek | 1900s, Fritz Theodor Benzen, Museum of Copenhagen | Undated, the Museum of Copenhagen (it says 1893, but that's wrong) | 1905, the Museum of Copenhagen | 1906 dated postcard, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1912, Torben Andreas Colding, Det Kgl. Bibliotek

Jesuskirken stood without a tower for a few years, until Jacobsen’s mother stepped in and funded its construction. Named Alftaarnet for Jacobsen’s ten-year-old son Alf who had died in 1890, architect Anton Rosen supervised the construction of the campanile, which was completed in 1895.

Still a functioning church of the Valby parish 135 years after opening, today Jesuskirken is a popular wedding venue for residents of Valby. Jesuskirken holds an open house the first Wednesday of every month from 10:00am to 12:00pm.

25th anniversary article, 1916 | Undated, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Undated with trains, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | Undated, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 1934 postmarked postcard, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 2006, Ib Rasmussen, Wikimedia Commons | Rear, 2006, Ib Rasmussen, Wikimedia Commons

Production Files

Further reading:

- Jesuskirken: en af Danmarks mest usædvanlige kirker gennem 125 år by Erik Udsen

- "From Beer to Bricks to Organ Pipes: Carl Jacobsen and the Jesus Church" by Sverker Jullander

- 75th anniversary booklet

- In Tidsskrift for Kunstindustri, 1895

- Jens Vilhelm Dahlerups liv og virksomhed, 1907

Decades before the Nazis claimed it and ruined it, Carl Jacobsen and Vilhelm Dahlerup were big fans of the swastika—besides Jesuskirken, it also decorates many buildings in the Ny Carlsberg brewing complex.

Undated, Holger Damgaard, Det Kgl. Bibliotek | 2025

Where I took the photo from.

That delightfully creepy statue is Trold, der vejrer kristenblod by Niels Hansen Jacobsen, "troll that smells Christian blood". Carl Jacobsen had it placed in front of Jesuskirken in the early 1900s, but locals found it unsettling and it was moved to the sculpture garden at Jacobsen's other public-private plaything, Glyptoteket. In the early 2000s the parish realized how great it was, so a copy was placed here.

Member discussion: