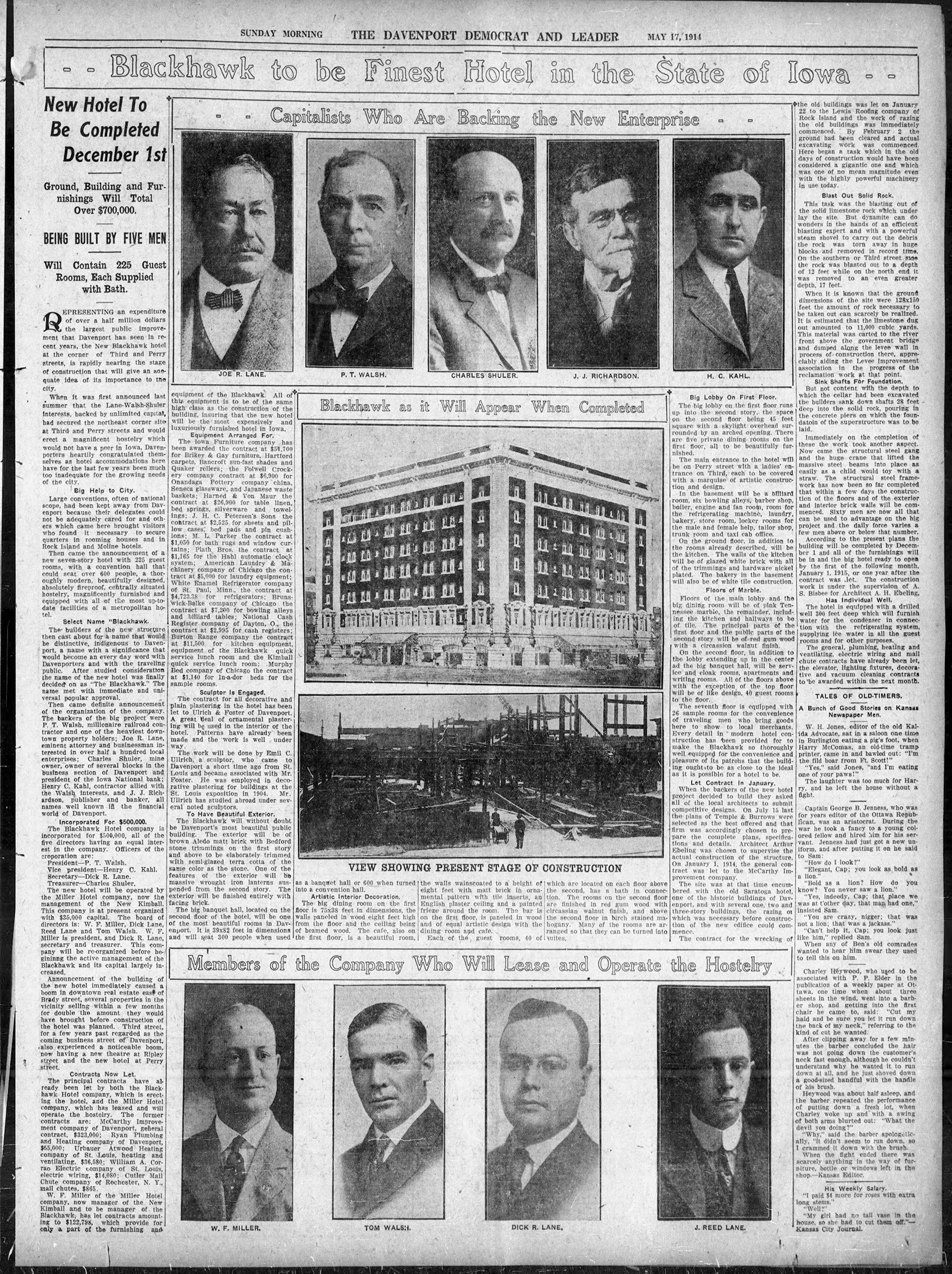

Davenport’s Hotel Blackhawk is part of a typology that, once you notice it, you’ll spot all over the US—enormous luxury hotels built in the 1910s or 1920s, usually by a group of “city father” types who incorporated a hotel company expressly for this purpose, designed in a grandiose revival style by a hometown hero architecture firm and built like a brick shithouse. A statement of power and a profit-making exercise. The ones that survived into the 21st century, like the Blackhawk, have also been a vital seed of revitalization for smaller downtowns–once the boast of a bustling downtown that had arrived, they’re now a key source of energy, prestige, and cultural capital for a downtown coming back.

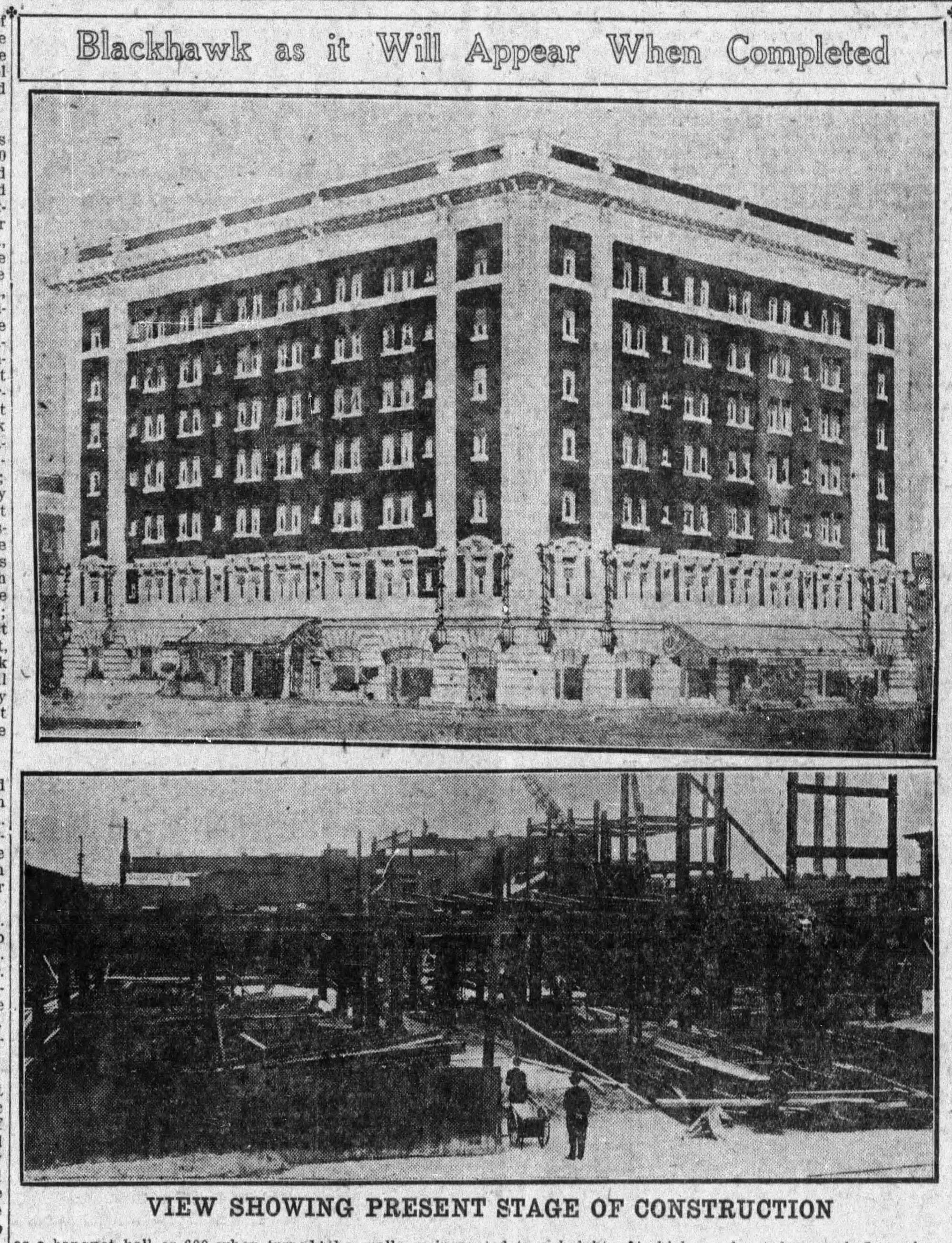

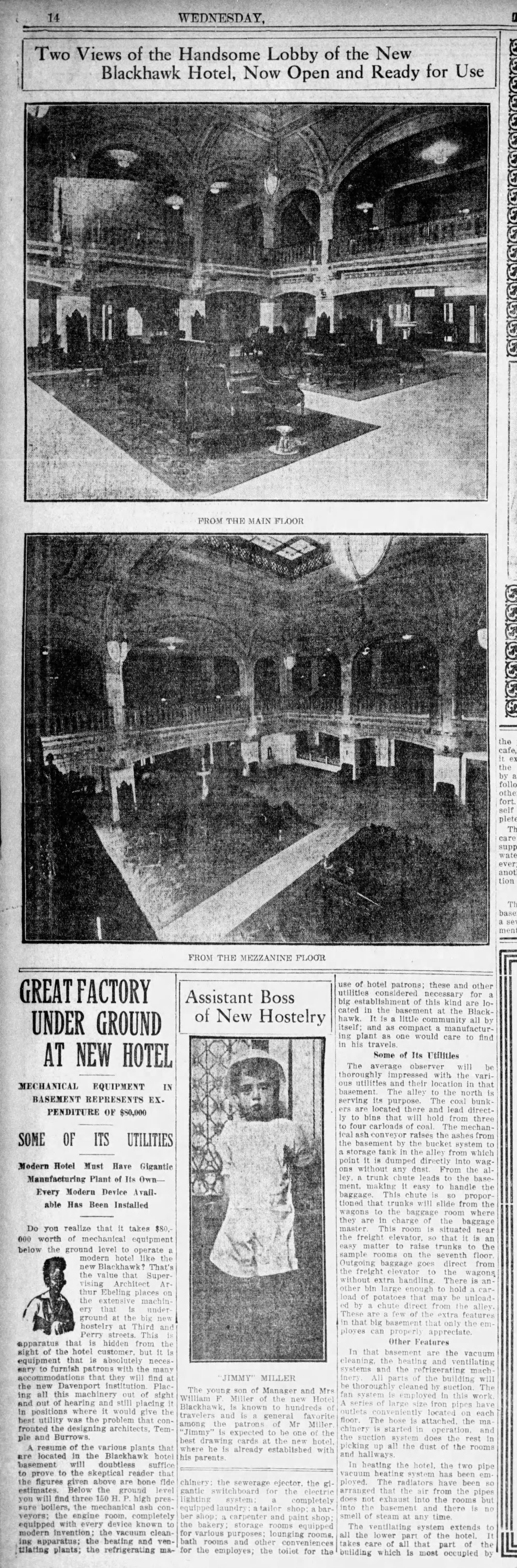

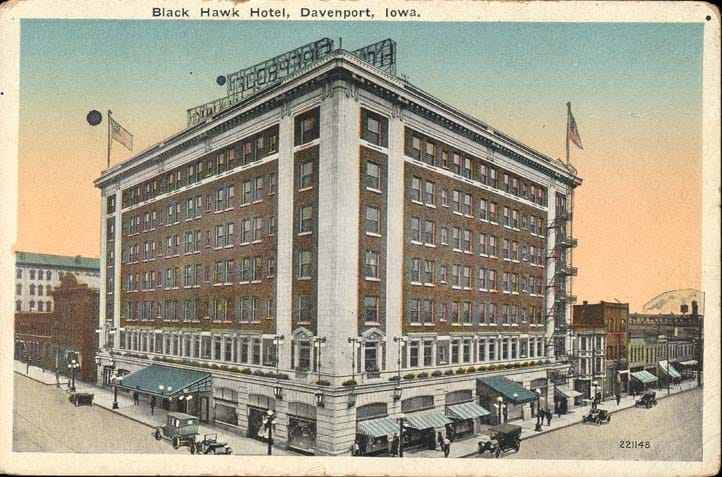

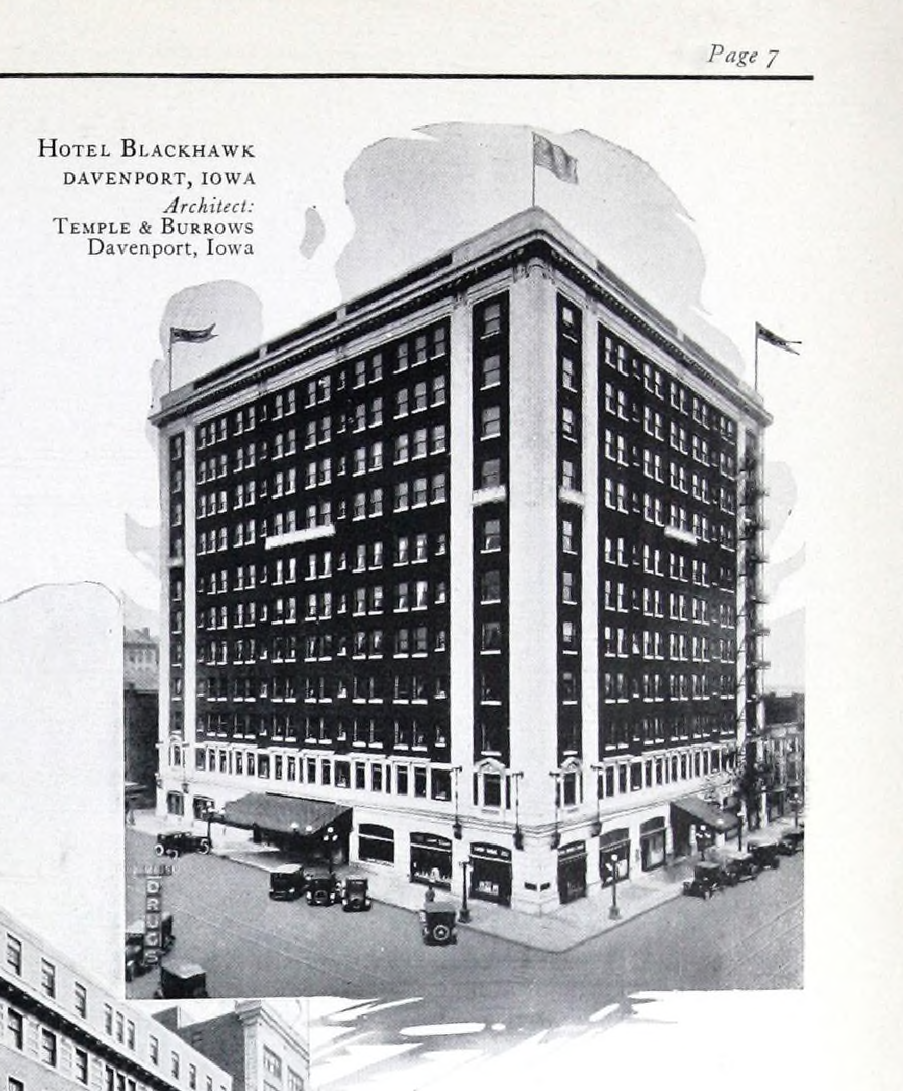

The Blackhawk was a massive 225 room fireproof hotel when it opened in 1915, designed in a vaguely Italian Renaissance revival style by locally-influential Temple & Burrows, and backed by five of Davenport’s wealthiest old white guys, who incorporated the Blackhawk Hotel Company to build a hotel good enough to impress their friends.

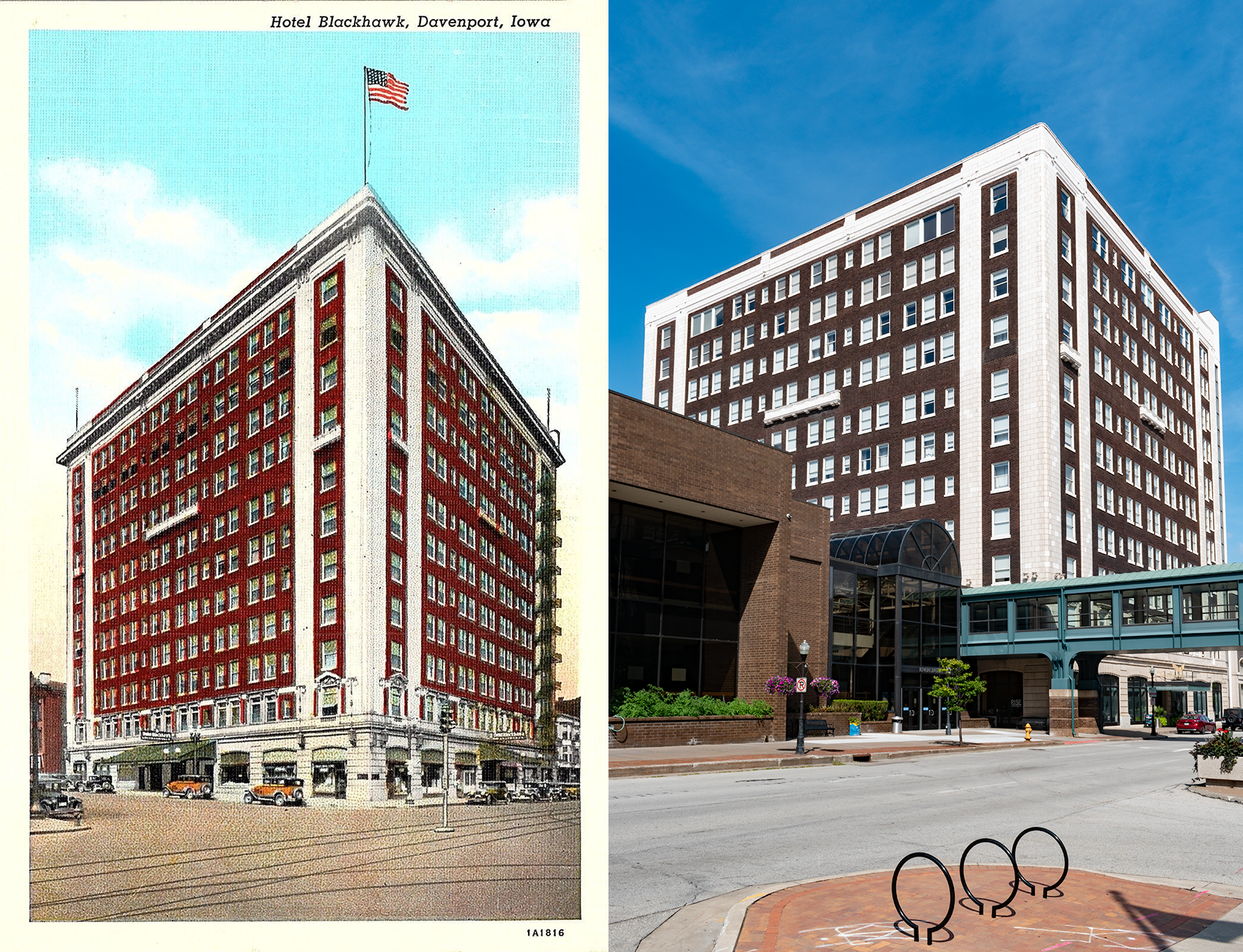

So what’s changed in 108 years?

- The cornice is gone (the cornice is always gone).

- Oddly, it lost only one of those little faux balconies on the 8th floor.

- The obsolete fire escape was disassembled at some point.

- The streetcar tracks were paved over by the 1940s.

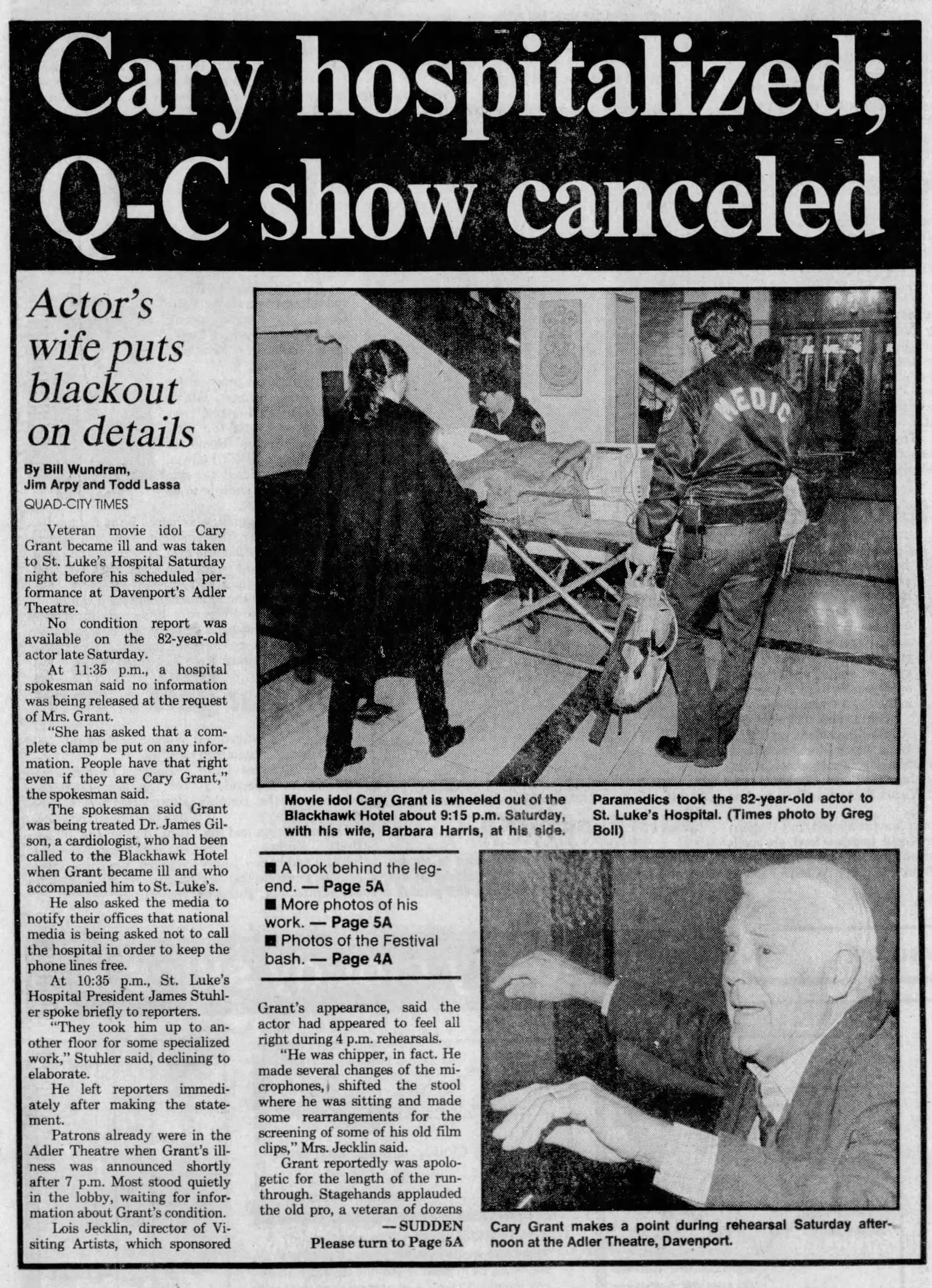

Given how snakebitten the Blackhawk was for much of the last 50 years—bankruptcies, a dead Cary Grant, a failed conversion to senior housing, and an 8th floor meth lab explosion that also caused serious water damage—it’s a victory that the building looks as sharp as it still does. Credit mainly goes to Amy and Amrit Gill, who bought and restored the hotel, reopening it in 2010. The biggest changes are to the neighborhood around it, really. Davenport paved over its streetcar lines in the 1930s, and the RiverCenter convention center—brown brick, dark glass, and skywalks designed by Roman Scholtz—landed in between the Blackhawk and the Adler Theater in 1983, knitting it all together in a deeply 1970s idea of economic development and civic planning.

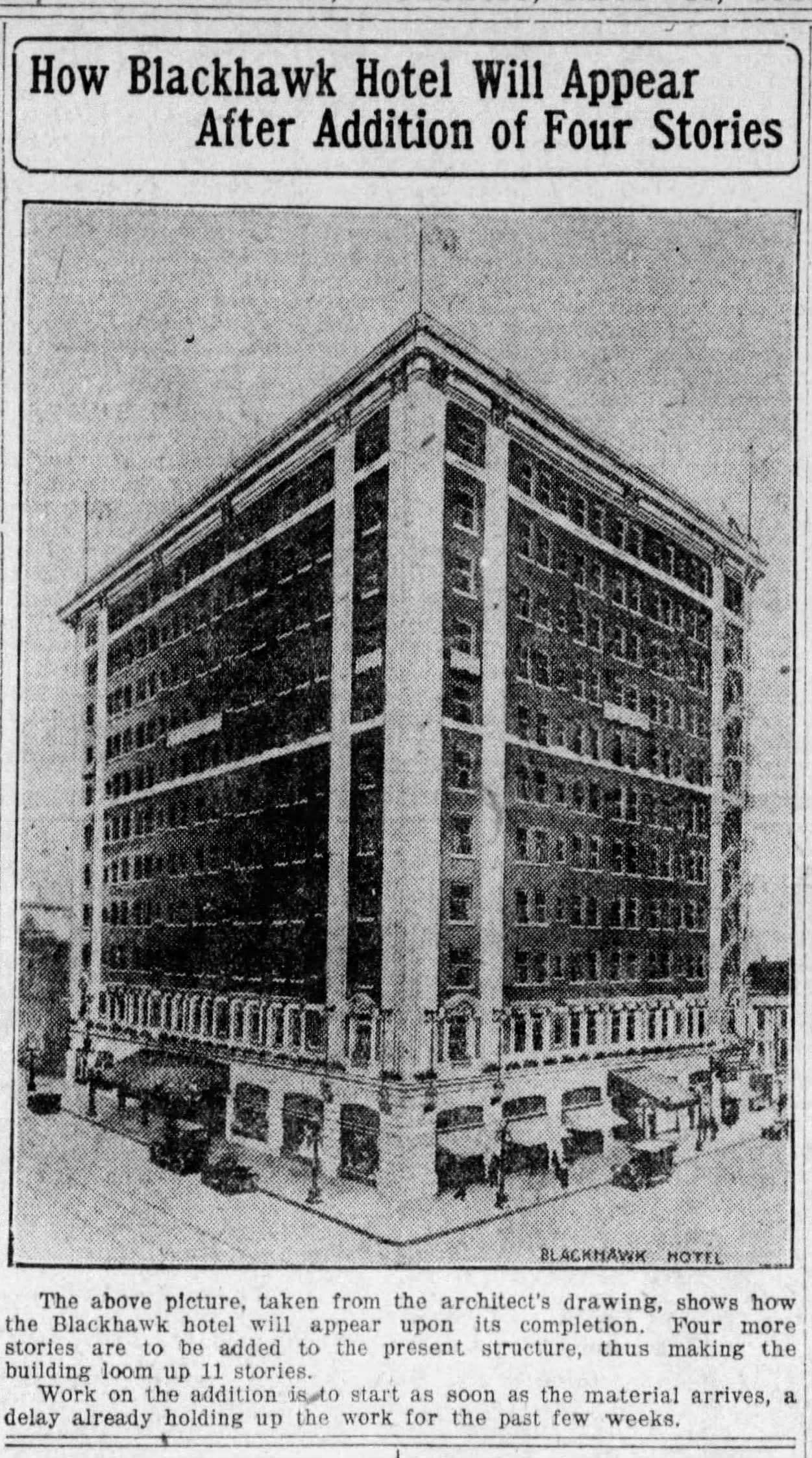

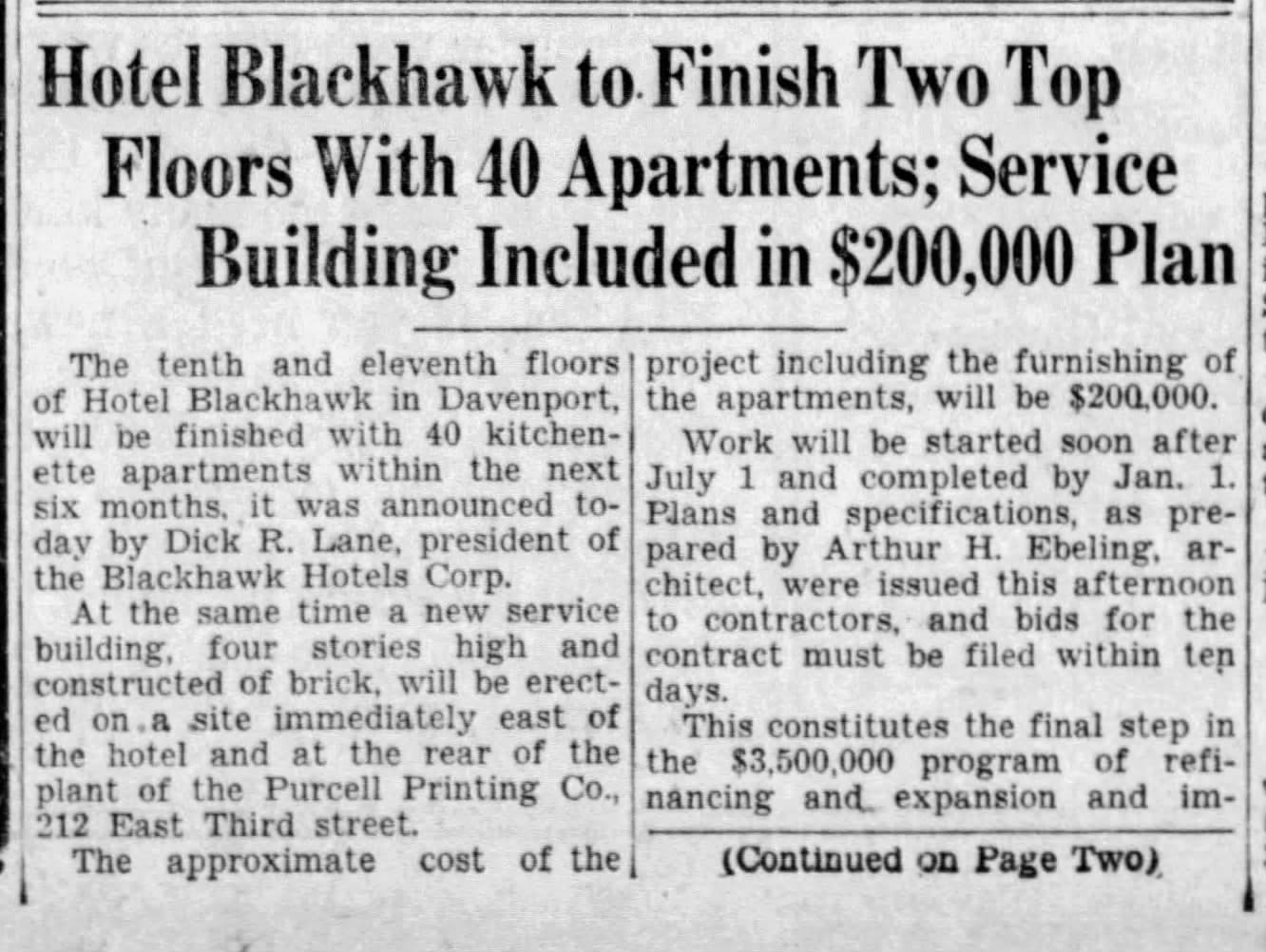

This postcard post-dates one of the biggest changes to the building—a 1920 addition, also designed by Temple & Burrows, added four floors. Two of those were left empty and unfinished until needed, which unfortunately meant until…1929. Can’t imagine that investment turned out well.

Temple & Burrows defined Davenport’s built environment as it grew around the turn of the century—Parke Burrows in particular. Prior to partnering with Seth Temple, he’d worked with Frederick Clausen, and between Temple & Burrows and Clausen & Burrows, Parke Burrows had a hand in a huge chunk of Davenport’s most important civic architecture from 1896 to the 1930s (including St. John’s ME Church). Before joining Burrows, Seth Temple taught architecture at University of Illinois, to students including Walter Burley Griffin. Here, Temple & Burrows worked with Arthur Ebeling as supervising architect.

1914 articles about the construction | 1915 articles about the opening | late 1910s postcard

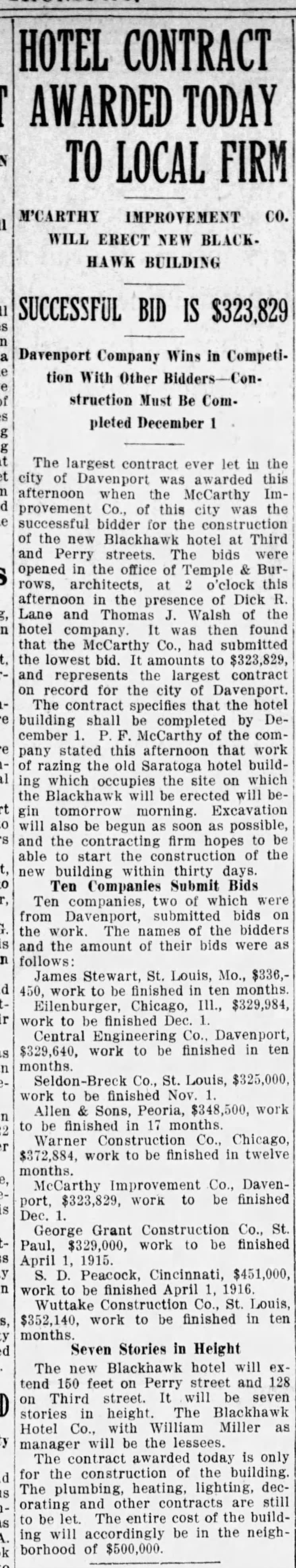

Davenport’s elite came together to form the Blackhawk Hotel Company in 1914—railroad tycoon, a lawyer, a mine owner, a banker, and a publisher. Partially built on the site of the Saratoga Hotel, construction here flew. Demolition of the Saratoga began in January 1914, and the completed (seven-story) Blackhawk opened for business in February 1915. Limestone excavated for the hotel’s foundation ended up on the banks of the Mississippi River, used by the Levee District’s reclamation work. Planned to have 225 guest rooms with a big ass banquet hall, dining room, cafe, barbershop, and a six-land bowling alley, the Blackhawk staked its claim as the best hotel in Davenport, the Tri-Cities, and maybe all of Iowa.

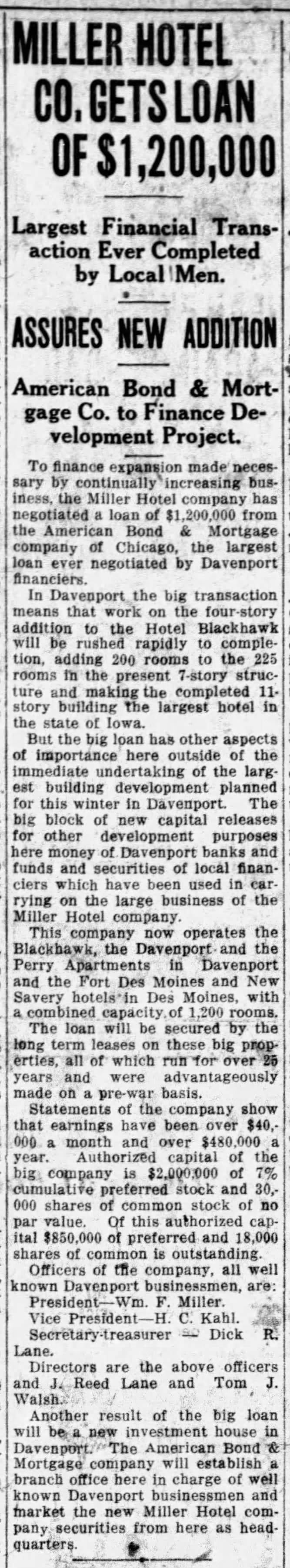

An immediate success, five years after opening the Blackhawk scored “the largest loan ever negotiated by Davenport financiers” to pay for a four-story addition. Besides catering to visitors, the Blackhawk was a residential hotel, providing short, medium, and long-term flexible housing to urban professionals until stigmatization and regulation squeezed them into virtual extinction starting in the 1950s.

1920 articles about the addition | 1925 ad | 1924, David D. Palmer Health Sciences Library of Palmer College of Chiropractic, Upper Mississippi Valley Digital Image Archive | 1925, J.B. Hostetler, Davenport Library via the Upper Mississippi Valley Digital Image Archive | 1929 article about finishing the top two floors | 1930, Davenport Library via the Upper Mississippi Valley Digital Image Archive | 1940s, Davenport Library via the Upper Mississippi Valley Digital Image Archive

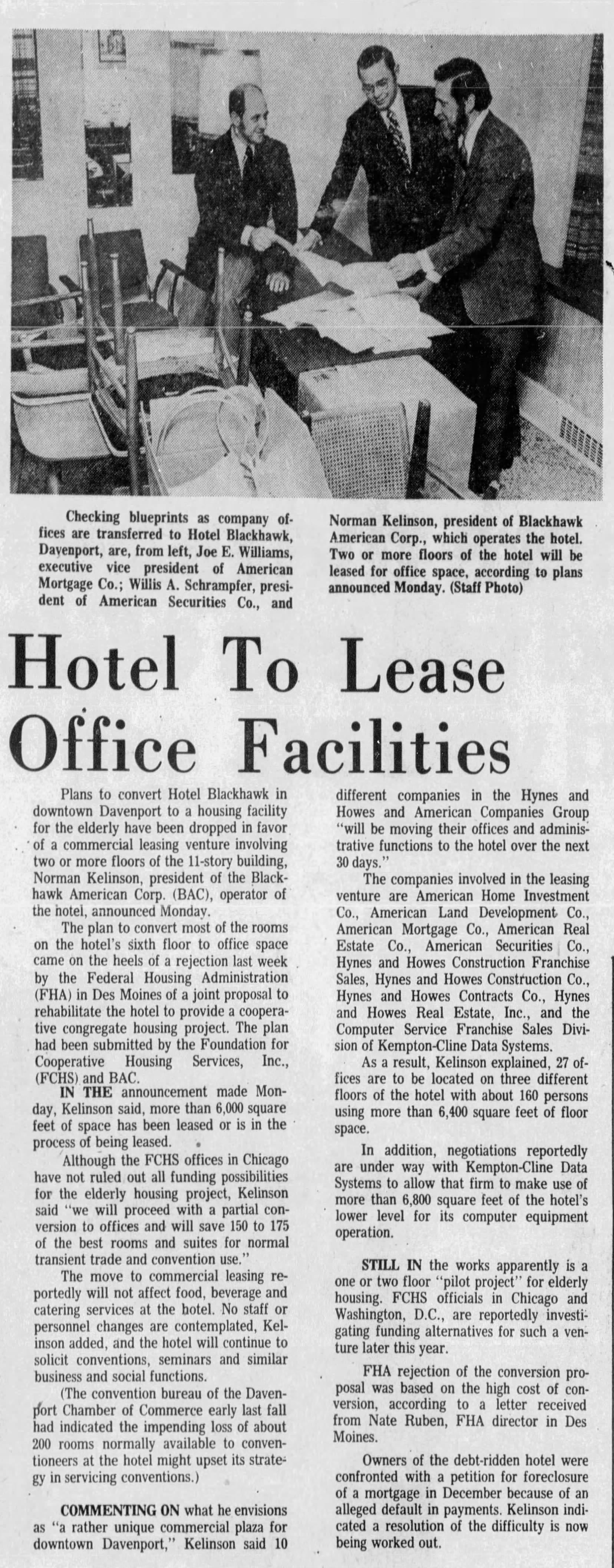

Urban renewal, deindustrialization, and white flight took chunks out of downtown Davenport in the 1960s, and the Blackhawk struggled. In the early 1970s, there were plans to turn the failing hotel into 300 units of affordable, subsidized senior housing, but the plan collapsed when the Federal Housing Administration refused to finance the loan. Instead, the bankrupt hotel was closed from 1974 until 1979.

A reopened Blackhawk anchored the early 1980s Superblock development that created a convention center in downtown Davenport, RiverCenter, and connected the hotel to the Adler Theater. In 1982 the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

1960s | 1967, Iowa Women's Archives | 1971, senior housing plan | 1972, office lease | 1980, NRHP nomination form | 1986, Cary Grant dies | 1989, develop John Connelly buys the Blackhawk

After the Iowa caucuses landed at the beginning of the primary schedule in the 1970s, the Blackhawk ended up hosting just about every US presidential candidate over the years—name one, they all stayed here. On the entertainment side, actor Cary Grant—in town for a performance at the Adler—actually died while staying at the Blackhawk in 1986.

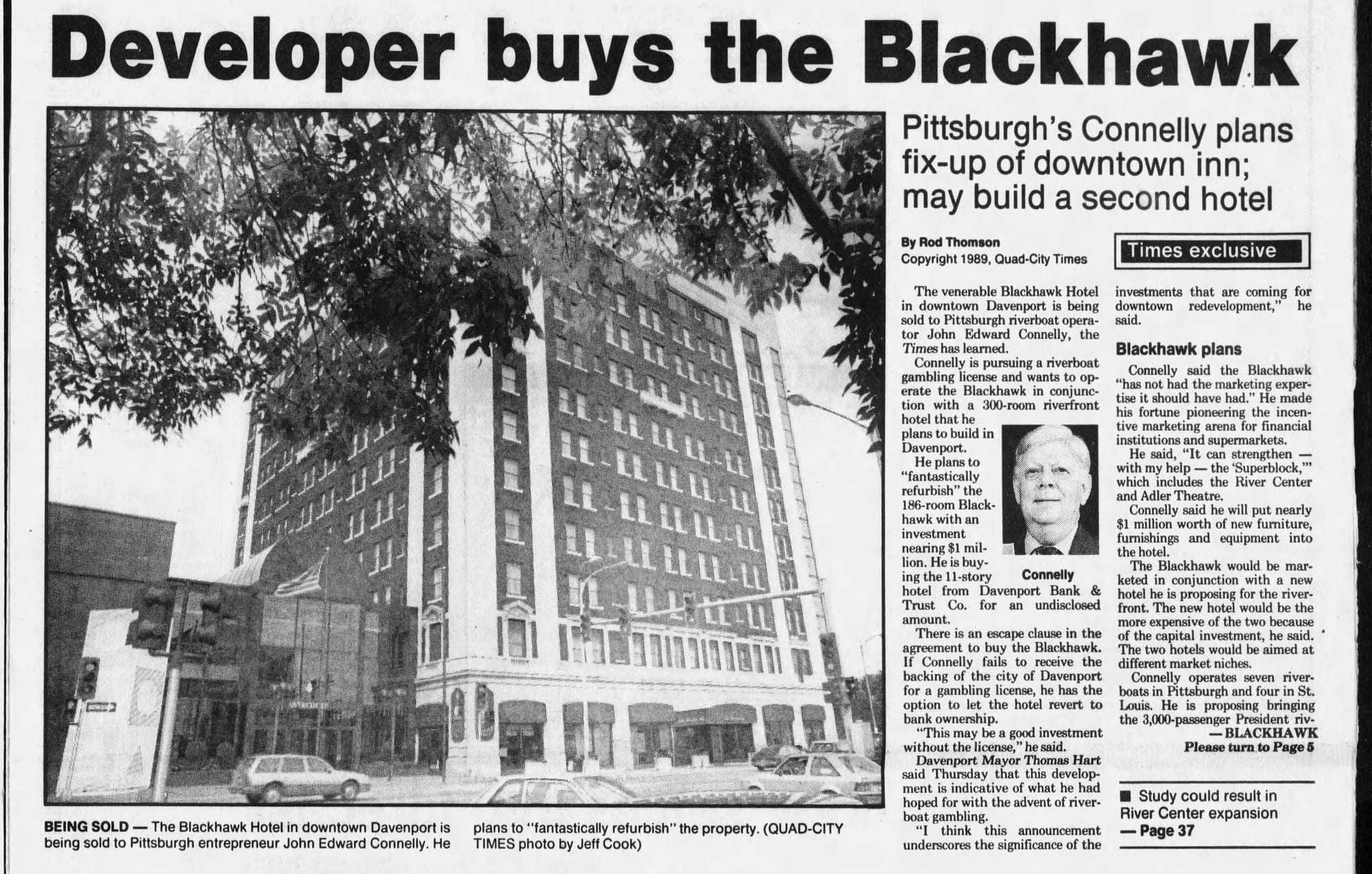

By the late 80s, the onetime 400+ room hotel was down to 186 rooms, as guest expectations around room space grew. The Blackhawk served as the hotel for various riverboat casinos, but by the 2000s the owner had closed its restaurant, cut back on guest services, and emptied the pool—it was struggling.

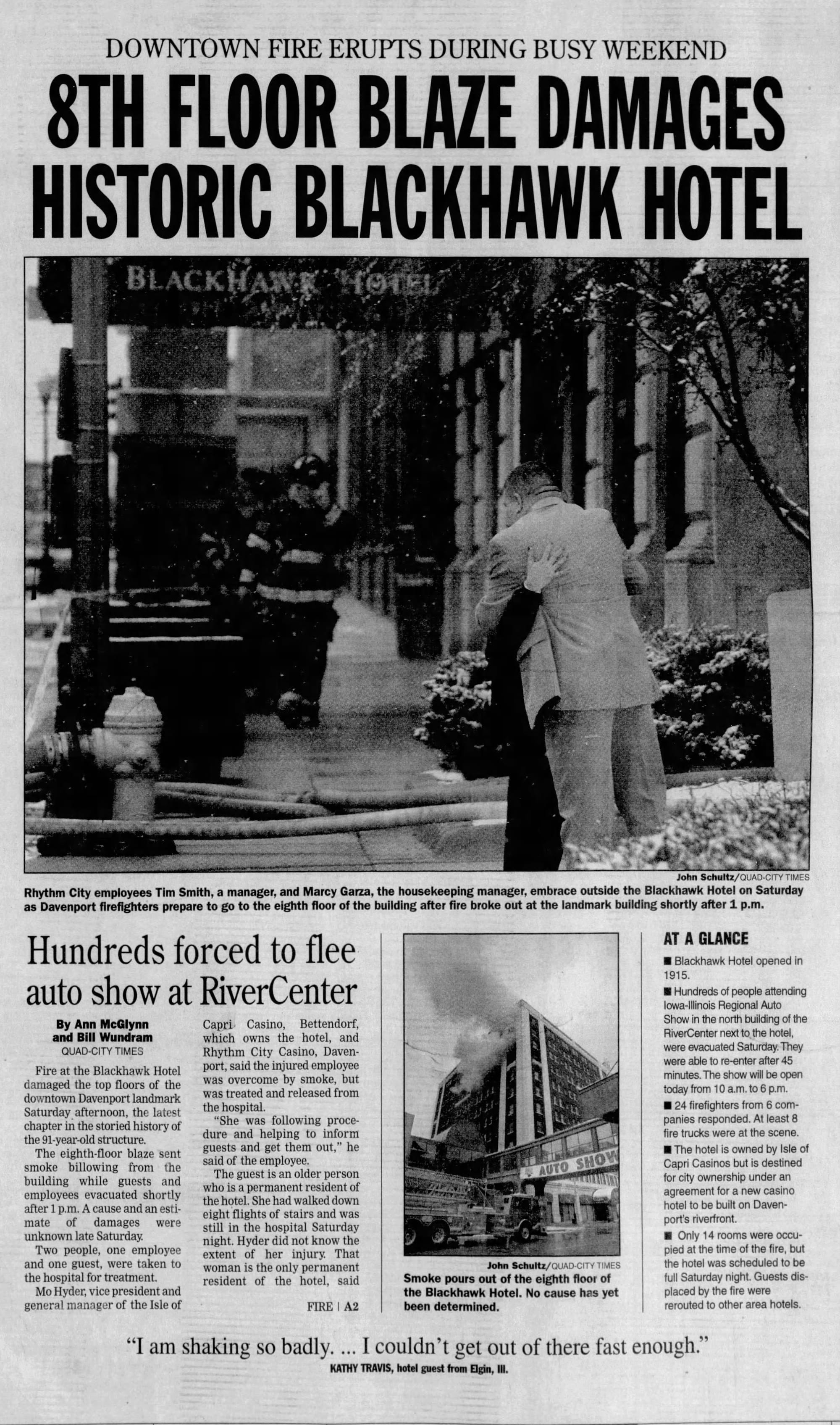

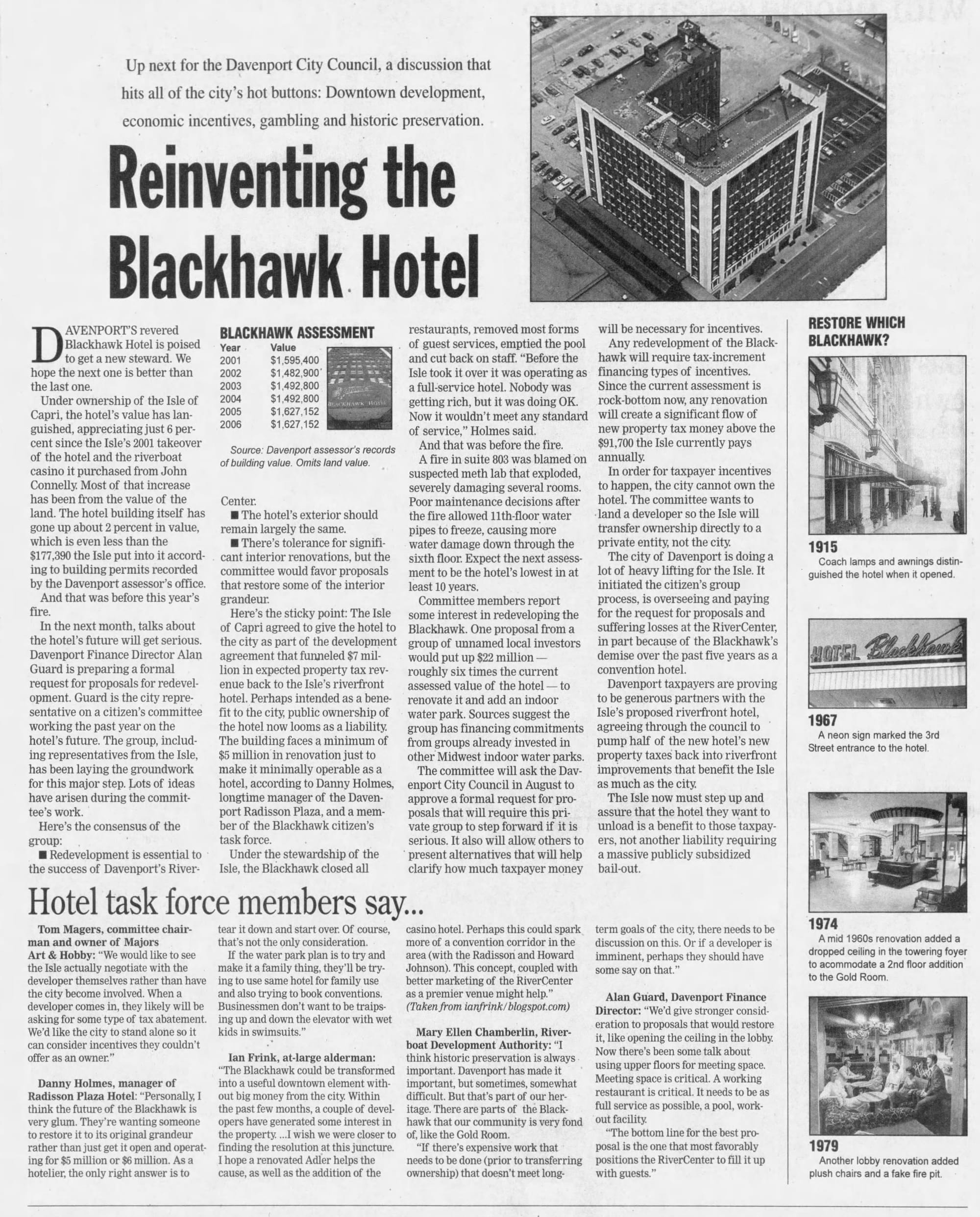

…and then a meth lab blew up in a guest room on the 8th floor. Not great–and that was before the hotel owner botched the maintenance after the fire, which led to burst pipes on the 11th floor and severe water damage all the way down. The damage shuttered the hotel, and owner Isle of Capri lacked the money and the interest to restore and reopen it—the Blackhawk was a lifeless hulk in Davenport’s downtown.

2006 articles on the fire and the effort to restore it afterwards | 2018, Wikimedia Commons | 2023

In a complicated deal facilitated by the city, hotel owner Isle of Capri ultimately transferred ownership to Restoration St. Louis for $10. That company, run by Amy and Amrit Gill, would—with the help of $13m in state and local government funding—restore the Hotel Blackhawk.

The Gills succeeded, with the Blackhawk reopening as a 130-room boutique hotel in 2010. Now operated as a Marriott Autograph Collection hotel, the restored Blackhawk provided some of the structure that the 2010s revitalization of Davenport was built on.

Production Files

Further reading:

- NRHP Nomination Form

- In the American Society of Civil Engineers Quad Cities Section newsletter

- Some great photos here

- Iowa Site Inventory Form, 2004

Member discussion: