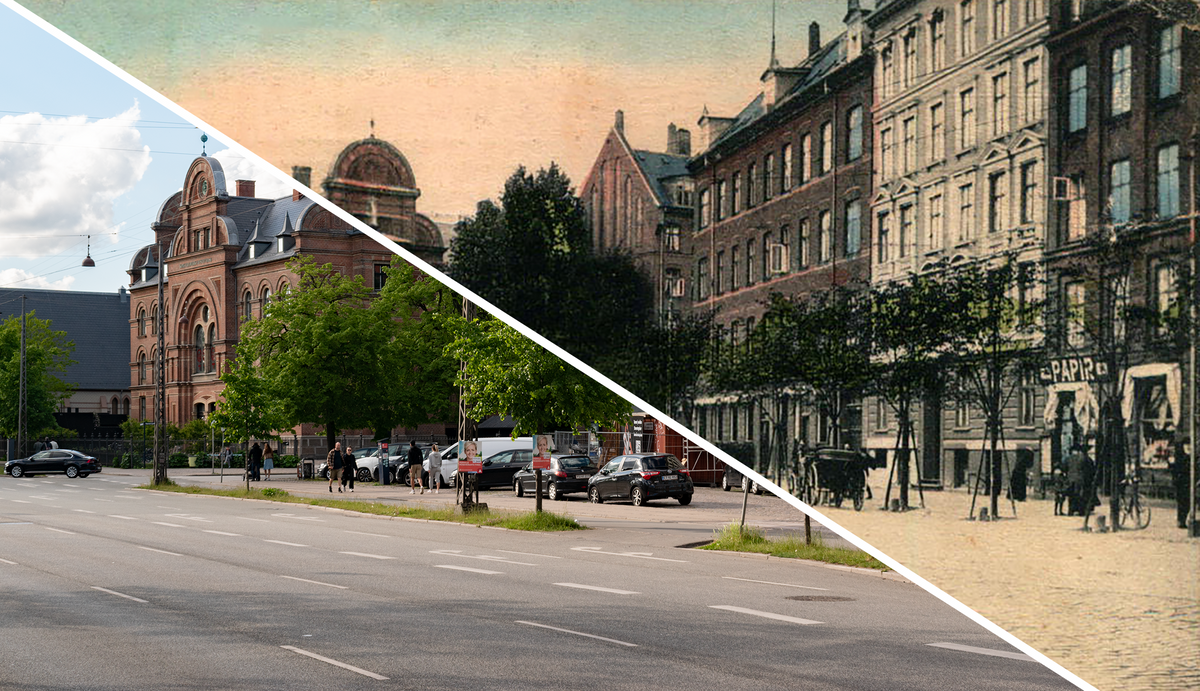

Gyldenløvesgade has changed remarkably little in the last 115 years or so–but that lack of visible change obscures a pretty wild story. That brick Neo-Renaissance building on the left with the eyecatching gables? Super interesting, it turns out.

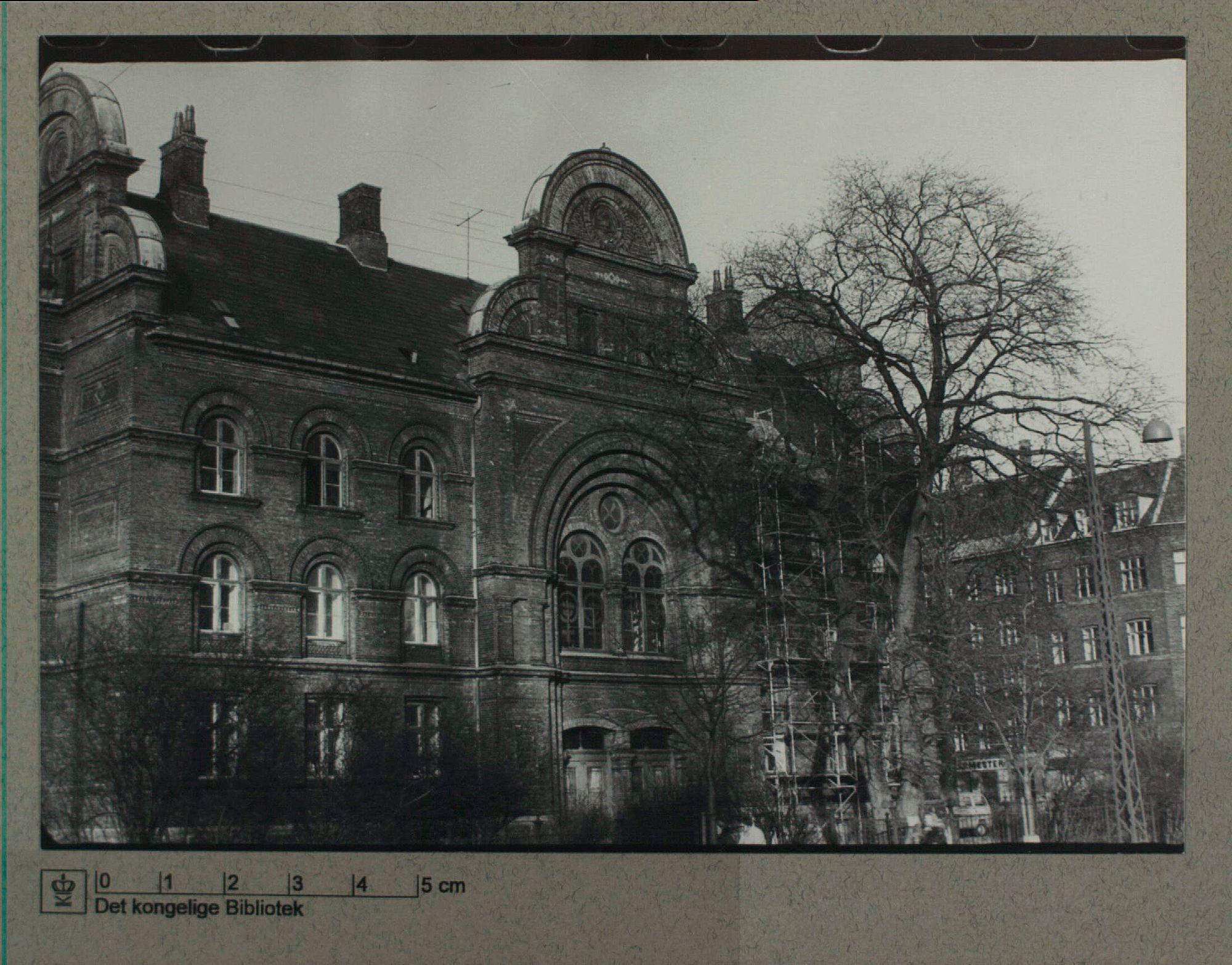

Built in 1875, it was home to the Kong Frederik den Syvendes Stiftelse for fattige Fruentimmer af Arbejdsklassen, a foundation endowed by Louise Rasmussen, Countess Danner, to house impoverished single women over the age of 40. By the 1970s, though, the generous Danish welfare state had mostly solved that particular problem. As the foundation wound itself down, the building was sold to a private company who intended to demolish it for a new office building. Determined to save Dannerhuset and maintain it as a refuge for women, grassroots activists pulled every lever imaginable, culminating in 300 women taking over the building in an audacious occupation in 1979. Direct action gets the goods–Dannerhuset was saved. Reimagined as a crisis center and shelter for women facing violence (and their children), a renovated Dannerhuset reopened in 1981. Now a professionalized international NGO, today Danner works to eliminate violence against women and children, and the building itself remains a shelter for up to 18 women and 18 kids.

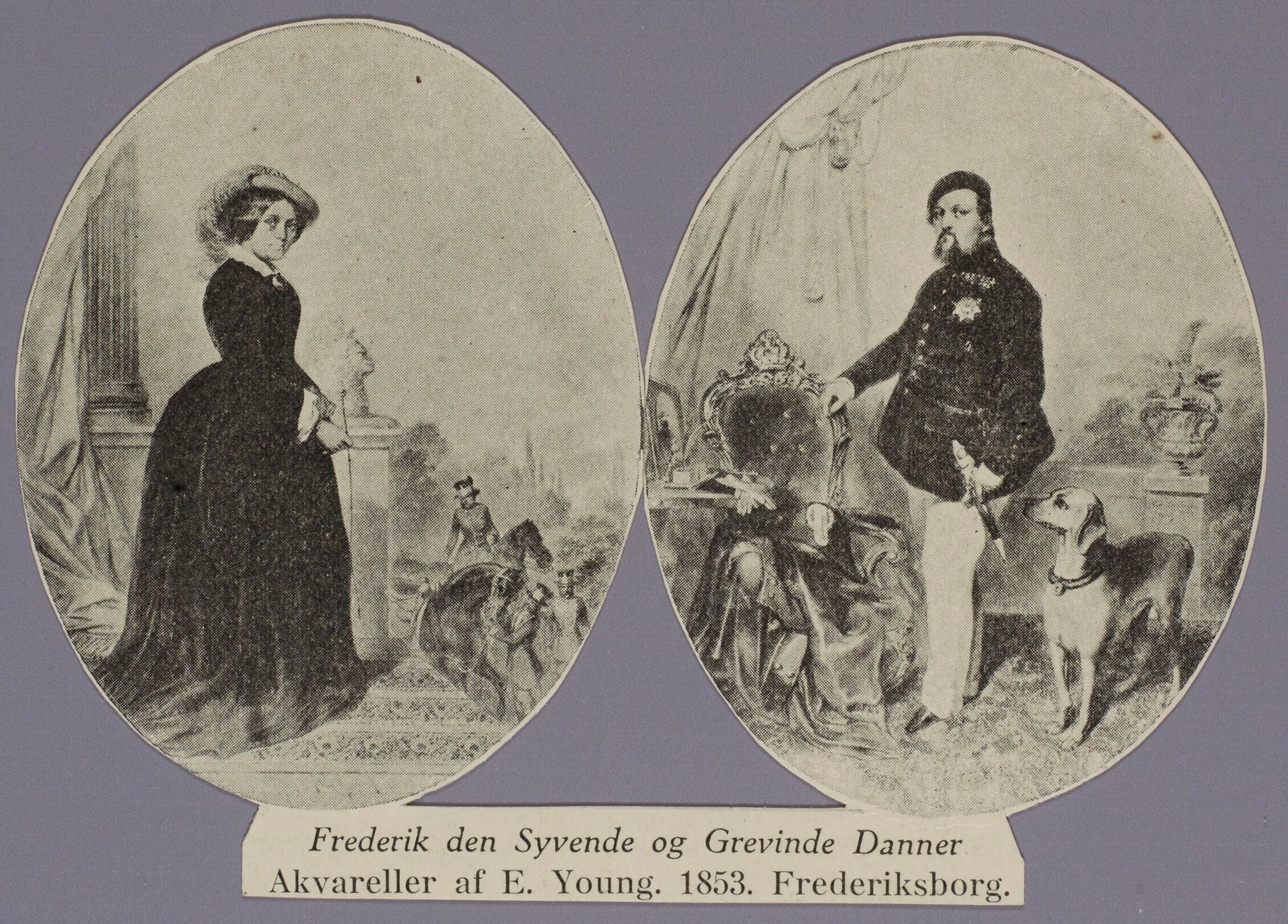

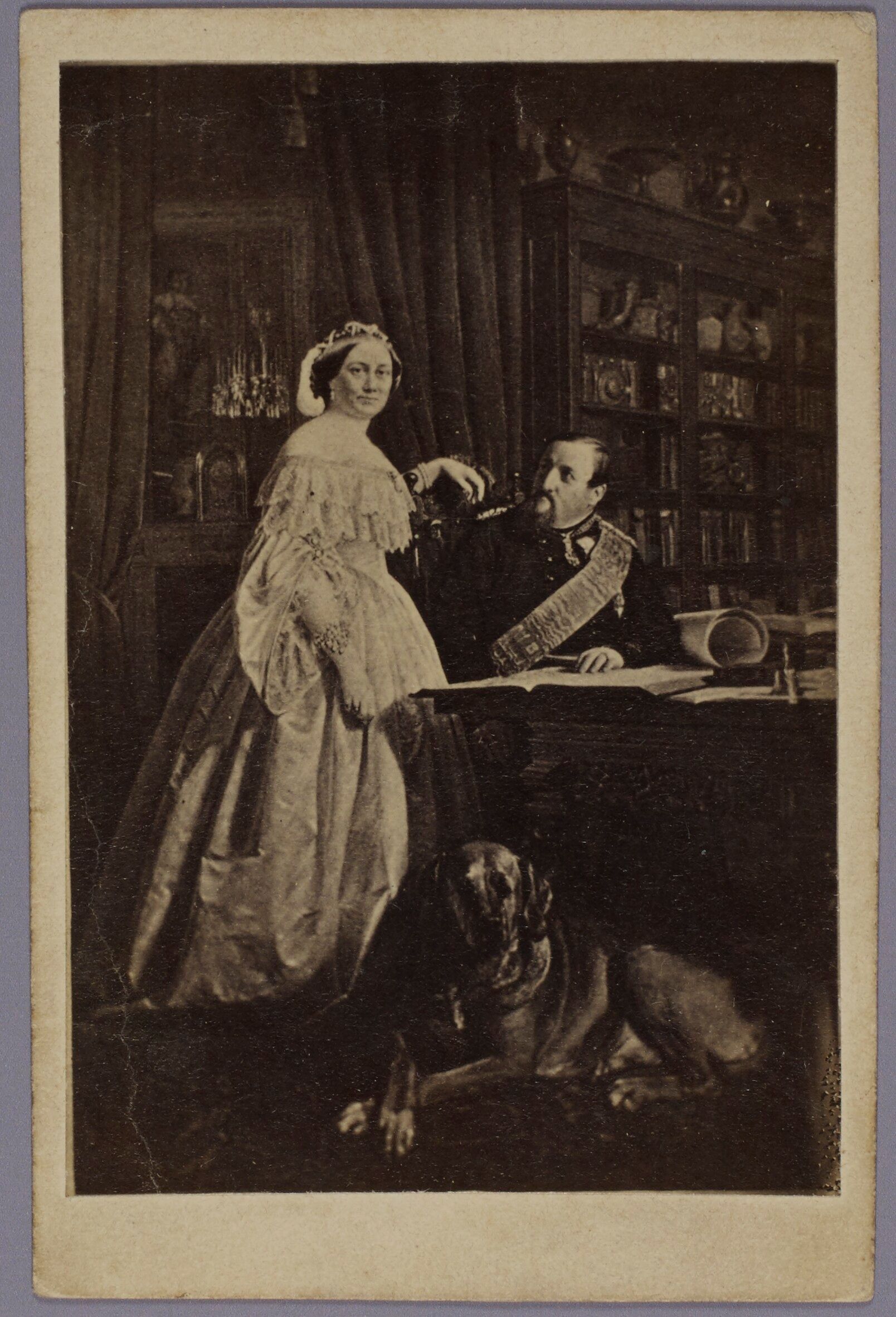

Louise Rasmussen, Countess Danner, was both a force and a scandal in mid-1800s Denmark. The illegitimate daughter of a poor maid, she’d rise to become the third wife of King Frederik VII–a momentous decision that threw the succession of the Danish throne into turmoil, as he’d never fathered a child. They met through Carl Berling, publisher of Copenhagen newspaper Berlingske, who’d met Rasmussen as she trained as a ballet dancer at the Royal Theater. Berling was close with Crown Prince Frederik (very close–they may have been lovers), and he also fathered a child with Rasmussen. Frederik was charming, unstable, and an alcoholic, but Rasmussen was apparently a steadying influence on him. So after two failed marriages and King Frederik’s signing of the Danish constitution–which turned the country into a constitutional monarchy–he was finally allowed to marry Rasmussen, who was granted the title Countess Danner. Danish high society never accepted Countess Danner, who they considered an upjumped gold-digger, but she, King Frederik, and her great love Carl Berling settled into a pleasantly eccentric equilibrium in the 1850s after he moved into Amalienborg with them (...plus Berling’s wife).

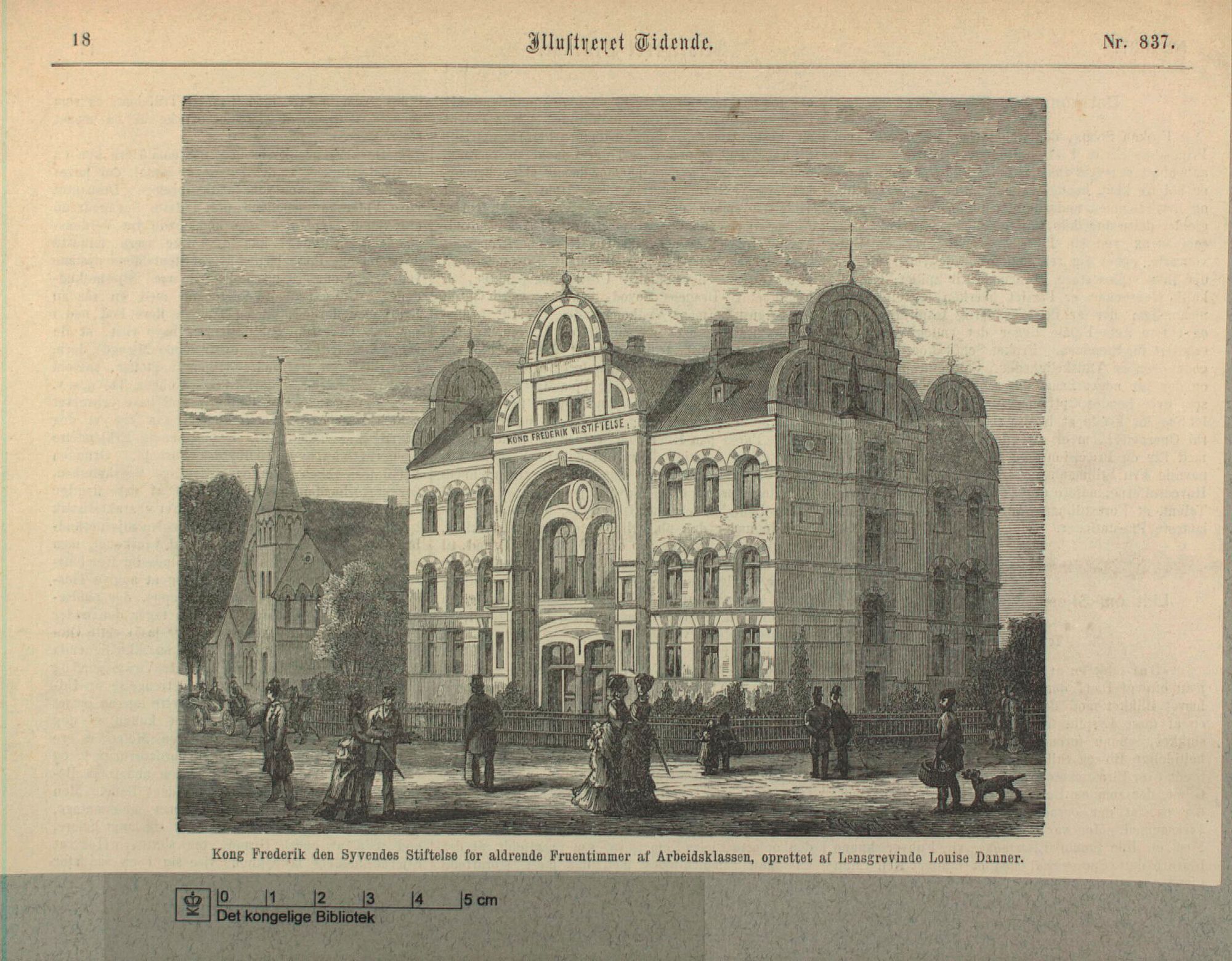

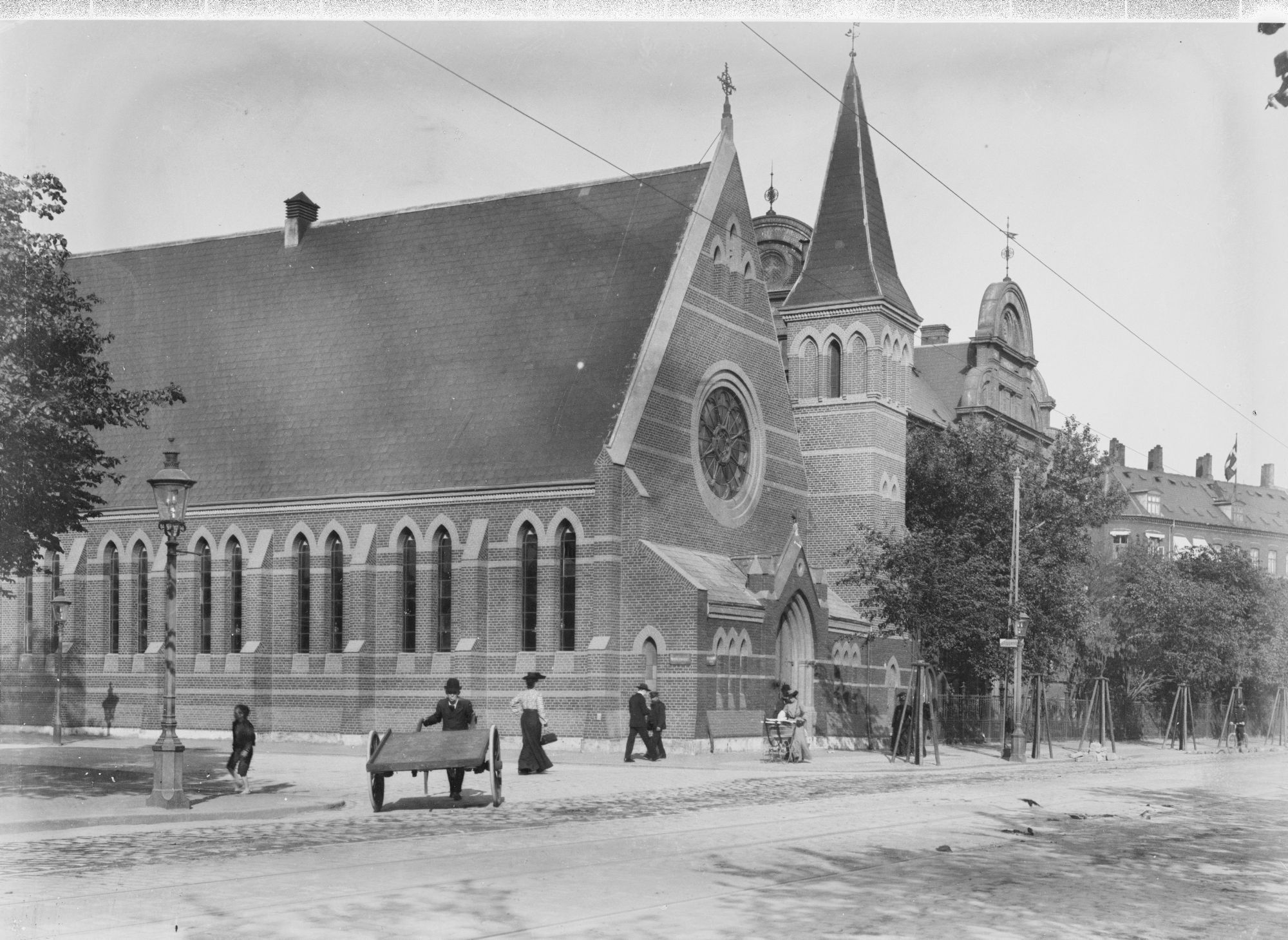

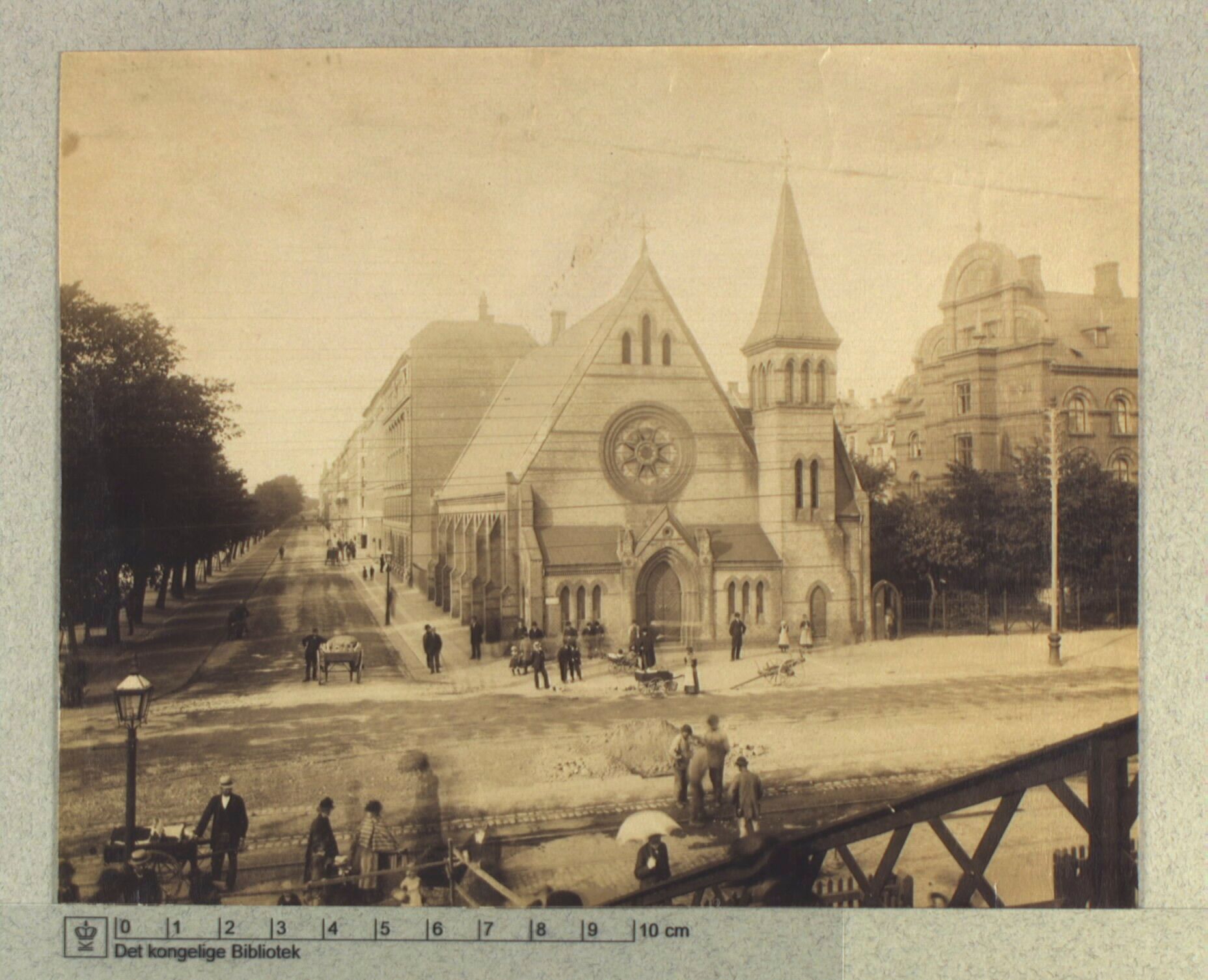

King Frederik VII, never in great health, died at the age of 55 in 1863, and Countess Danner retired to a quiet life in the countryside. In her husband’s honor–but clearly aimed at an issue close to her own heart–she founded Frederik den Syvendes Stiftelse for fattige Fruentimmer af Arbejdsklassen, which would provide housing for poor single women over 40. She hired her husband’s favored architect, Theodor Zeltner, to design the building. Zeltner, who managed construction at Christiansborg for Frederik VII, mainly did historicist renovation work on royal properties like Moltkes Palæ and Jægerspris Slot (although he did design Hylleholt Kirke in Faxe). Countess Danner and King Frederik clearly had an unusual relationship, but it strikes me as a mildly poignant symbol of affection that the cornerstone of this building was laid on their anniversary in 1873.

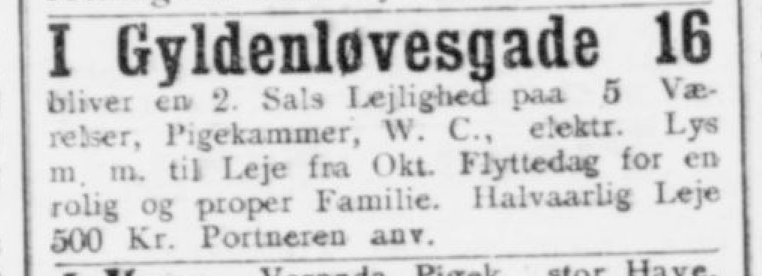

Alas, Countess Danner died in 1874, before her plans for the building came to fruition. Dannerhuset opened in 1875, providing a home for 52 women (although 54 lived there initially–two pairs of sisters shared rooms). Residents didn’t pay rent, but did buy their own food and fuel (for heat). Unlike today’s Dannerhuset, these were not temporary stays. By 1915, a couple hundred women had found free housing here, and it appears that once they arrived, they stayed. The majority of residents in that year were over 70, and the oldest two were 90 and 91–a testament to its success, I’d say.

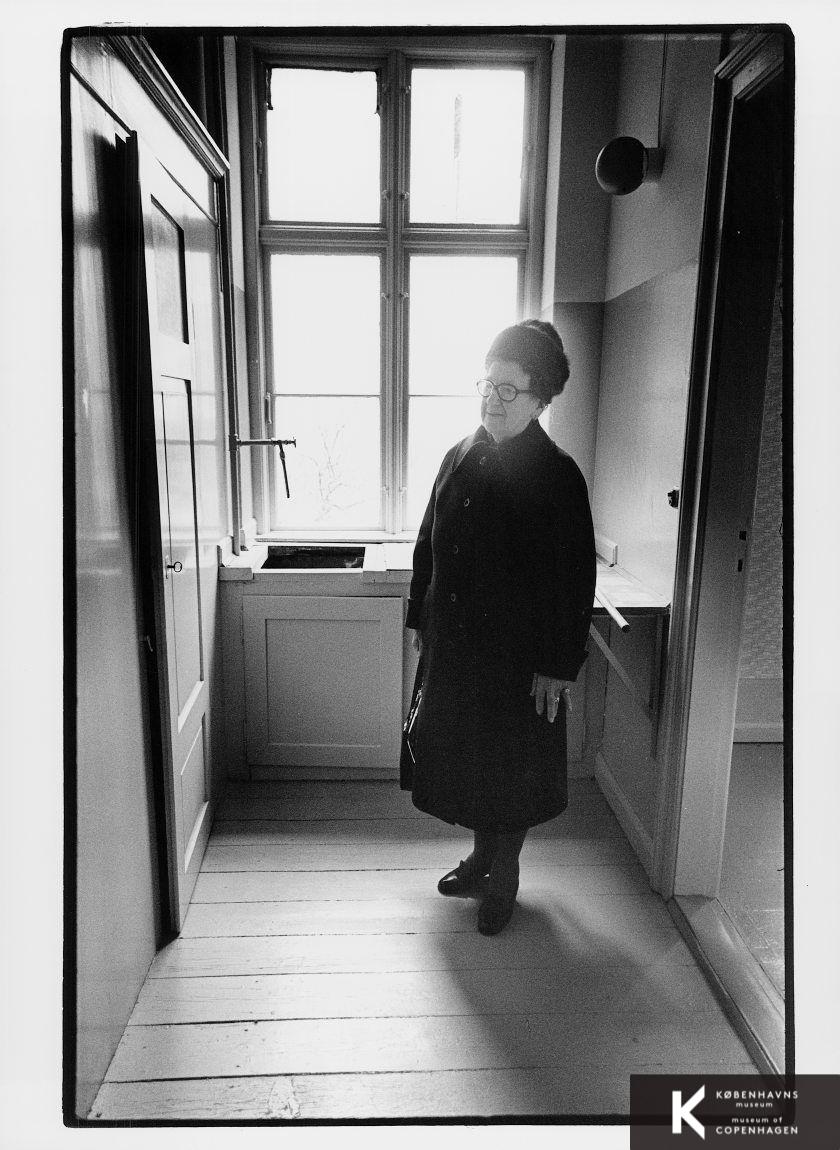

The population the foundation served was pretty narrow, though, and after the Danish government established the modern Danish welfare state in the 1950s and 1960s, the poverty rate among single women over 40 plummeted. Its raison d’etre diminished and the building fell into disrepair. From 54 residents at its opening, by the late 1970s only four women still lived here, and the foundation began to wind itself down. They sold the building to construction company A. Jespersen & Son, who planned to demolish and replace it with a modern office building.

Led by the Danish Women’s Society and the left-wing feminists of the Red Stocking Movement, a grassroots coalition of Danish women launched a multi-pronged campaign to take over the building, save it from demolition, and continue Countess Danner’s legacy. Working every possible avenue, they appealed to the Ministry of Justice, the Municipality of Copenhagen, the Danish Conservation Agency, and other foundations to step in and save Dannerhuset.

The sale of the building to A. Jespersen & Son required sign-off from the Ministry of Justice–an opportunity. To pressure the ministry, build public awareness, and physically prevent demolition, an audacious plan was hatched to occupy the building. On the night of November 2nd, 1979, the four building residents opened the door and 300 women from the Red Stocking Movement streamed in over the course of the night, occupying the building. There’s something poetic about that–Dannerhuset of old quite literally opening the door for Dannerhuset of the future.

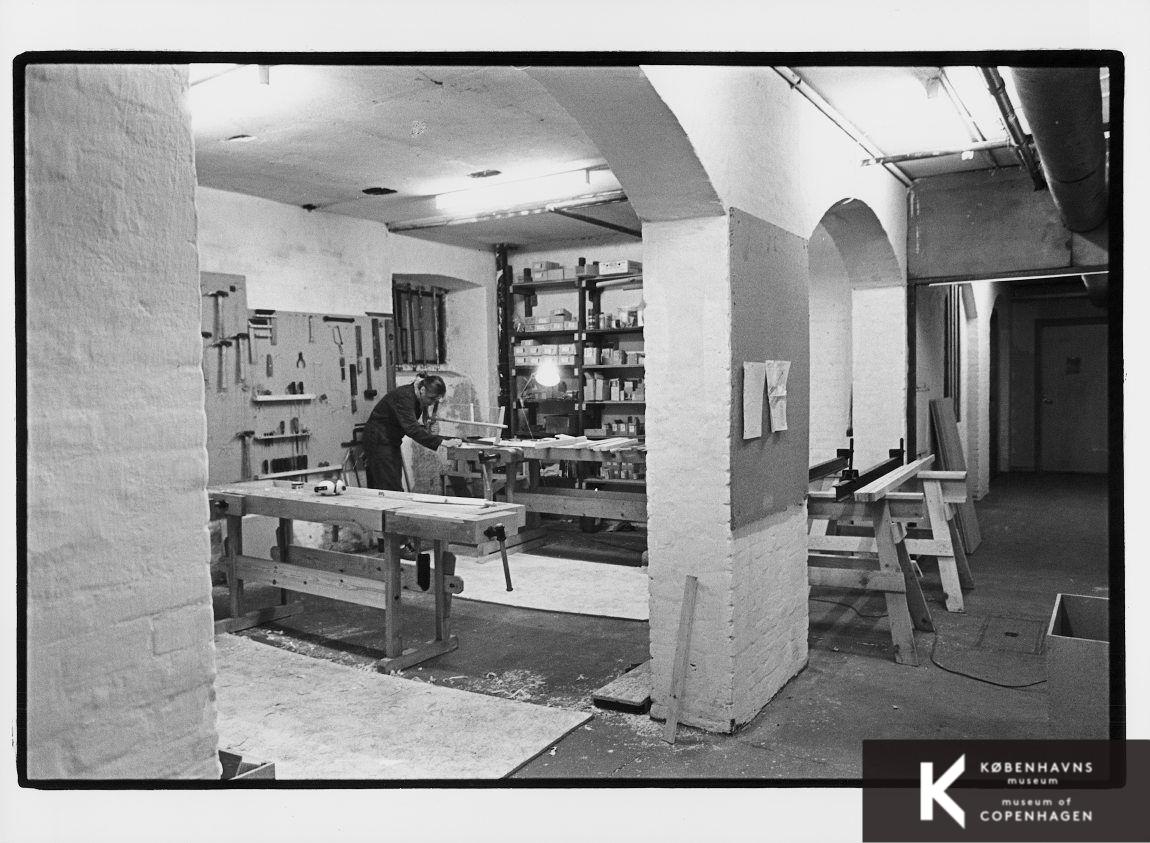

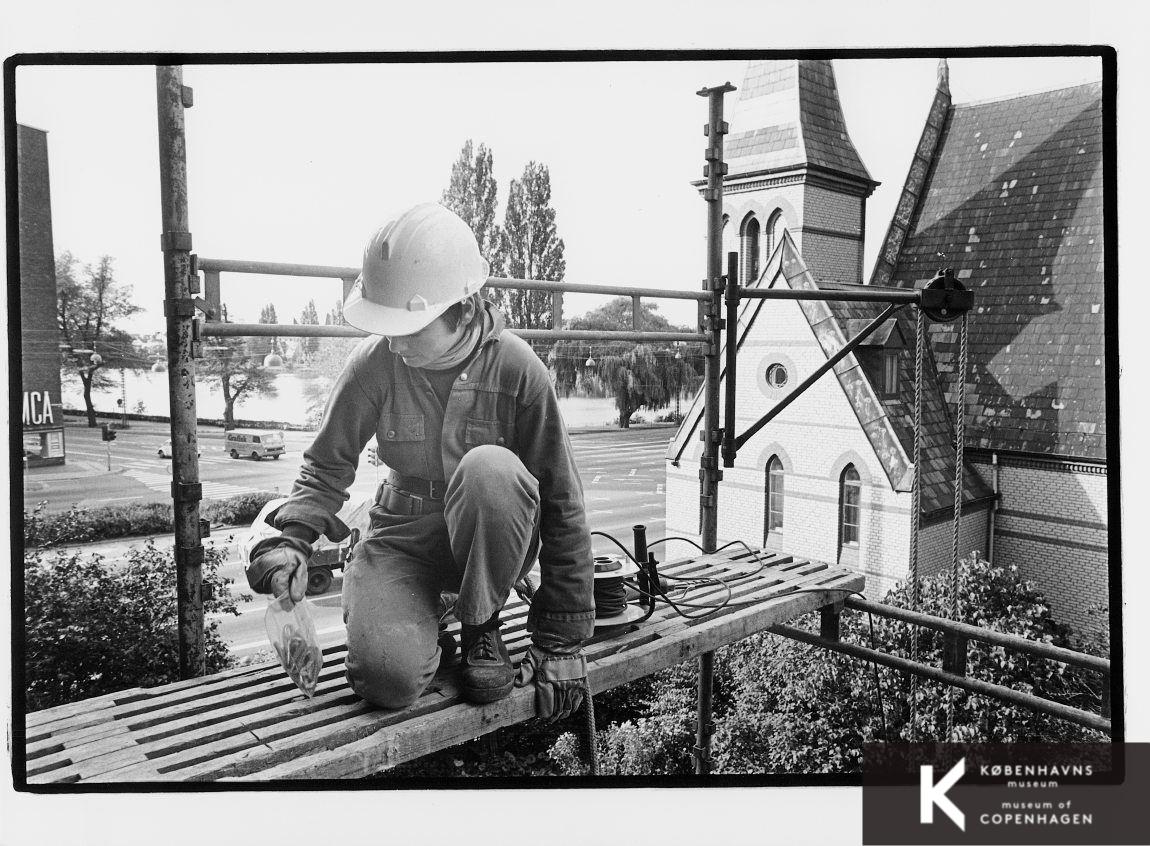

The activists' first success came in December of 1979, when the Danish Conservation Agency listed the building for conservation, killing A. Jespersen & Son’s plan to demolish it. While the building itself was saved, there was still no guarantee it would be maintained as a social refuge for women–they needed to raise the money to buy the building. Galvanized by the success of their occupation and leveraging the public attention that it brought to their cause, a broad-based grassroots fundraising operation quickly pulled together enough money to buy the building. Renovated by an all-women team, a renewed Dannerhuset reopened as a crisis center for women experiencing violence in 1981.

From its beginnings as an all-volunteer grassroots crisis shelter, Danner began to slowly professionalize through the 1990s, then fully in the 2000s, its work growing to include international advocacy on ending violence against women and children. An award-winning renovation from 2008 to 2012 by Varmings Tegnestue retained the history while bringing the building into the future. With space for 18 women and 18 kids, today more than 50 people a year are sheltered at Dannerhuset. It took creativity and direct action, but nearly 150 years later the building is still a refuge for women in Copenhagen.

As for the rest of Gyldenløvesgade, these buildings were built in the 1880s. Origianlly home to a lively and very normal mixed-use of apartments, offices, stores, and cafes, they remain home to a...lively and very normal mixed-use of apartments, offices, stores, and cafes.

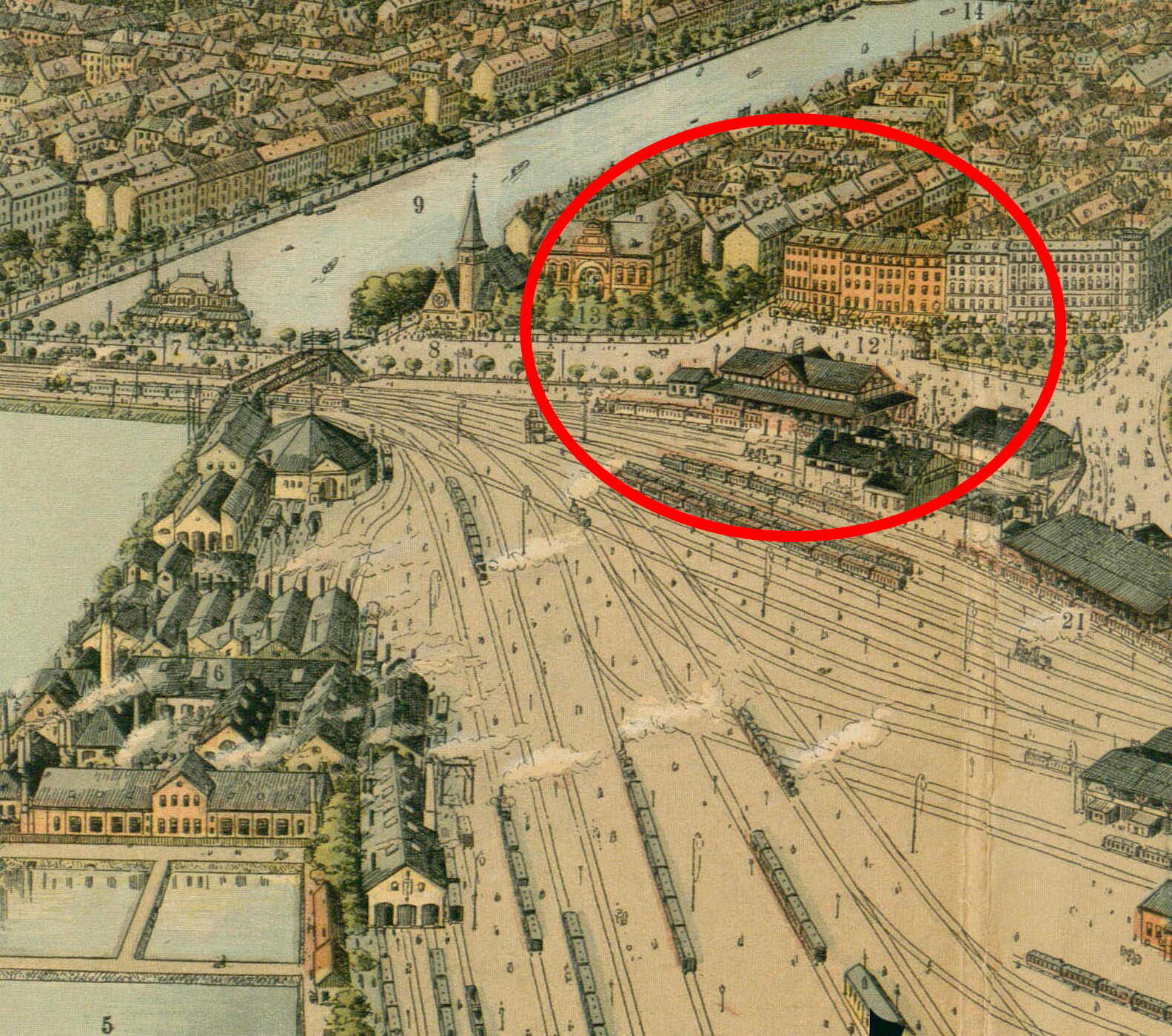

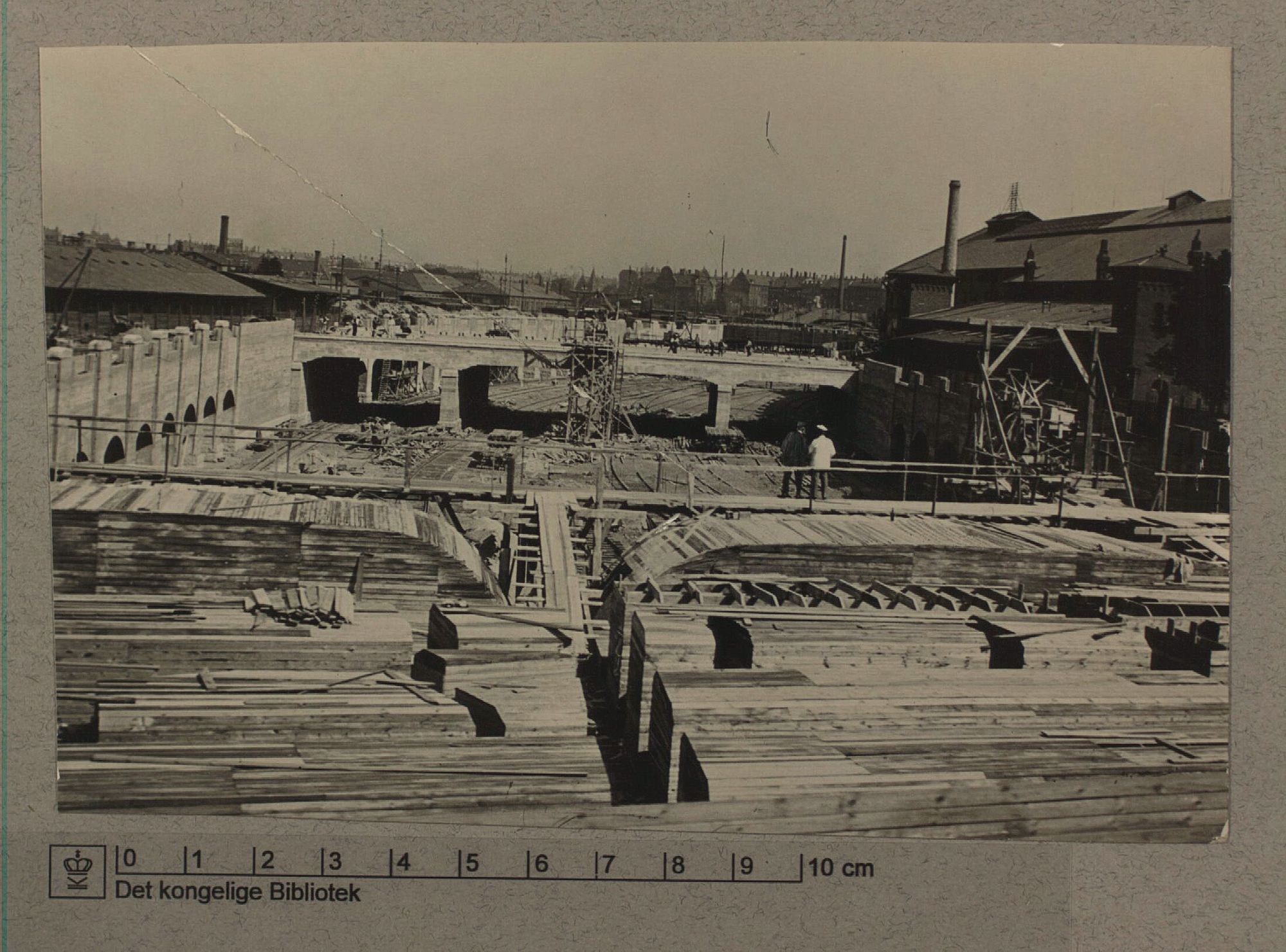

For me, the biggest surprise here is that Gyldenløvesgade's shittiness–it's an ultra-wide car sewer that's unpleasant (by Copenhagen standards) to bike or walk on–predates the automobile. Turns out that this was the original route of the Klampenborg Railway. The second Klampenborg-banegård stood here from 1887 until 1921. Upon the completion of the Boulevard Line in 1917, which connected the Coast Line to Central Station, trains to Klampenborg were rerouted. These tracks, made redundant (at least at the time), were ripped up and the station demolished in 1921.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Danner's history, in their own words

- The conservation listing from Slots- og Kulturstyrelsen

- Some great stuff in this project overview from Varmings Tegnestue, who did the 2010s restoration

- The Realdania overview of the restoration

- On the 1979 occupation: "Da det private blev politisk: 300 kvinder besatte Dannerhuset med soveposer og sang"

- 2010 article on the restoration and professionalization of Danner, "I grevindens ånd"

- 1980 article "The fight over the Countess' House" (PDF)

- A very helpful comprehensive read on Klampenborgbanen and Klampenborg Station

Member discussion: