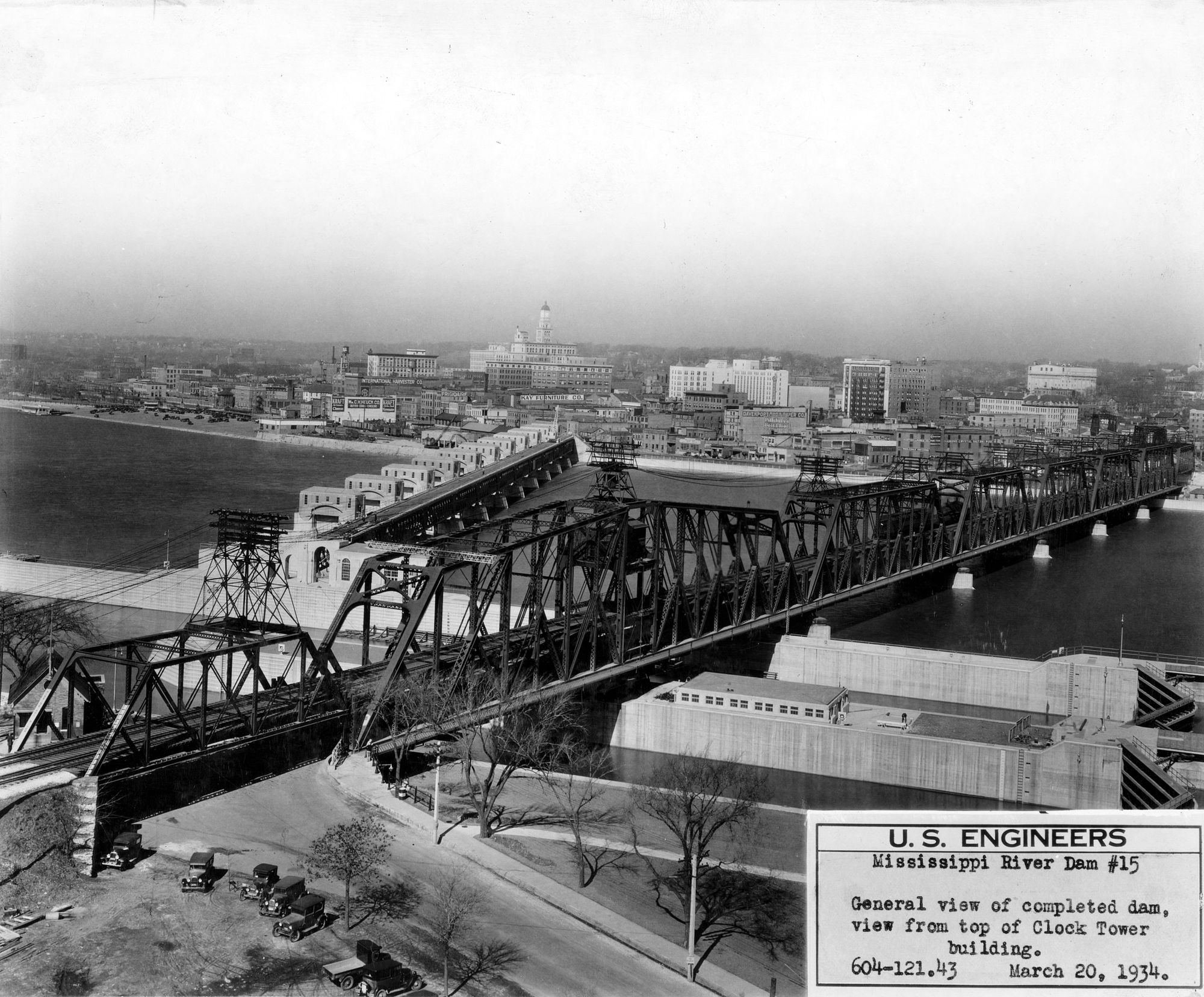

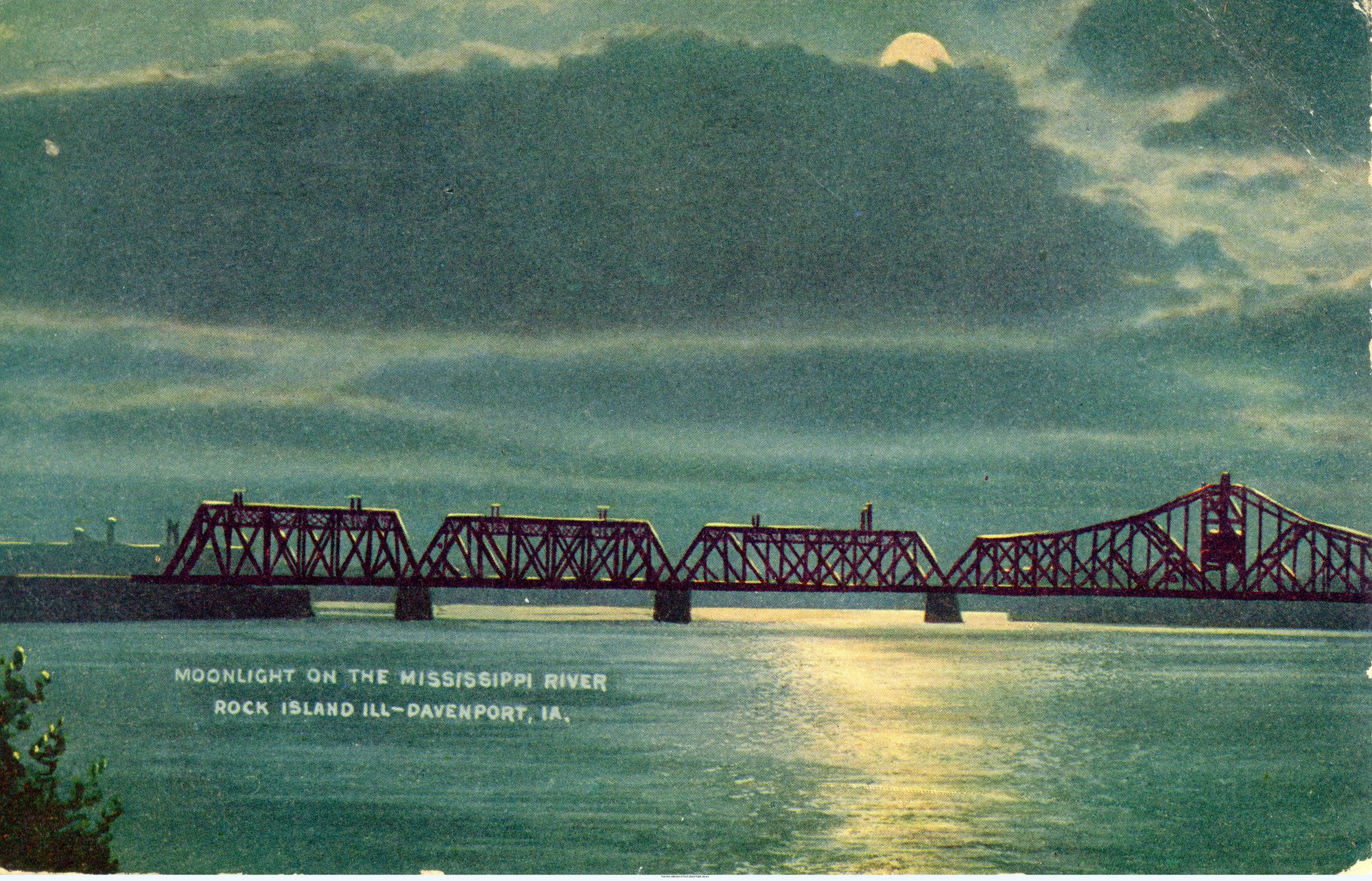

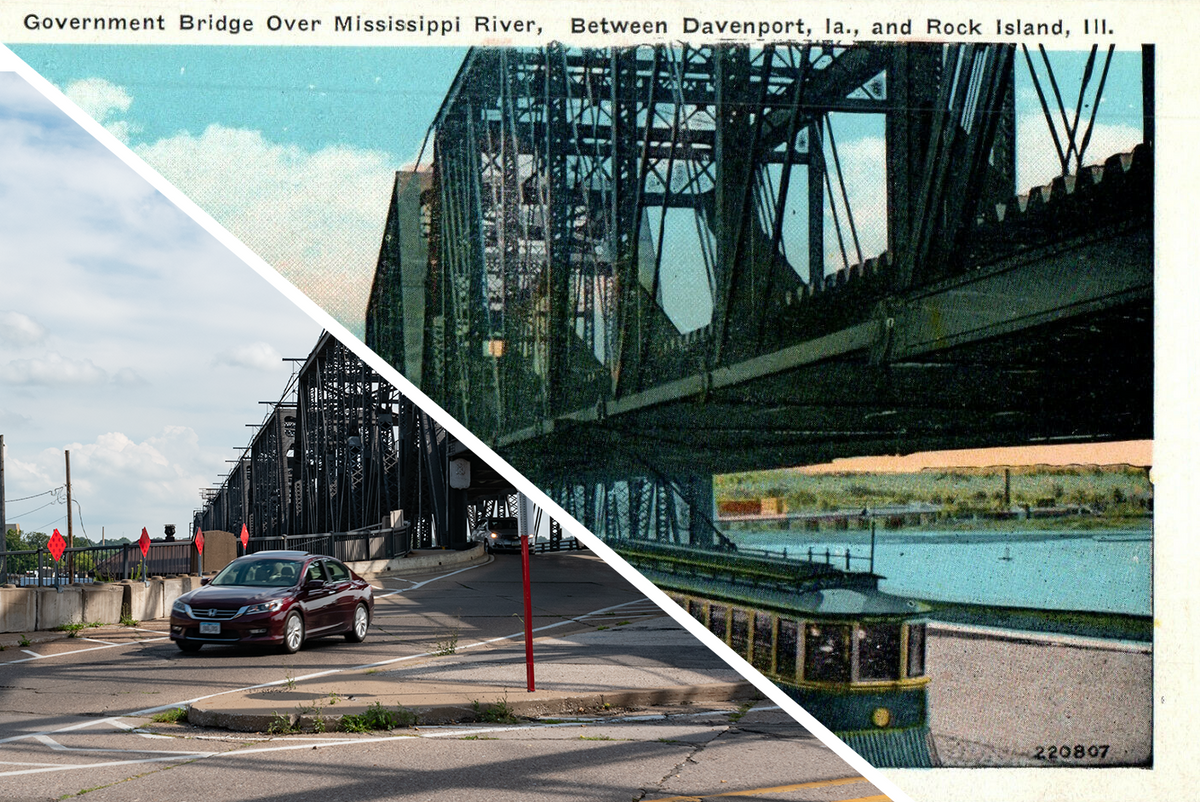

The spiritual heir to the first railroad bridge to cross the Mississippi River, this is actually the fourth bridge connecting Davenport to Rock Island’s Arsenal Island. Completed in 1896, the Government Bridge is a twin-deck steel truss swing bridge with rail above and everyone else below (including the Quad Cities long-gone streetcar system). It was the first major commission for Polish-American bridge builder Ralph Modjeski, who’d become one of the most prolific bridge engineers in the US. His firm, Modjeski & Majors, is still around more than 125 years later…and they’re even hired for the occasional project on the bridge that launched their namesake’s career, most recently in 2019.

First things first: what’s changed? (excuse the slightly different angle–i couldn’t [...ehh, wouldn’t] climb up onto the railroad viaduct)

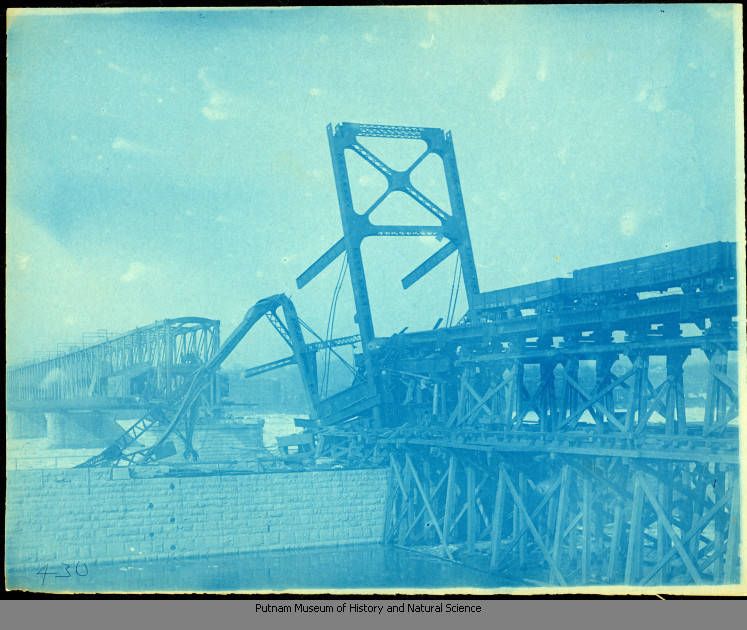

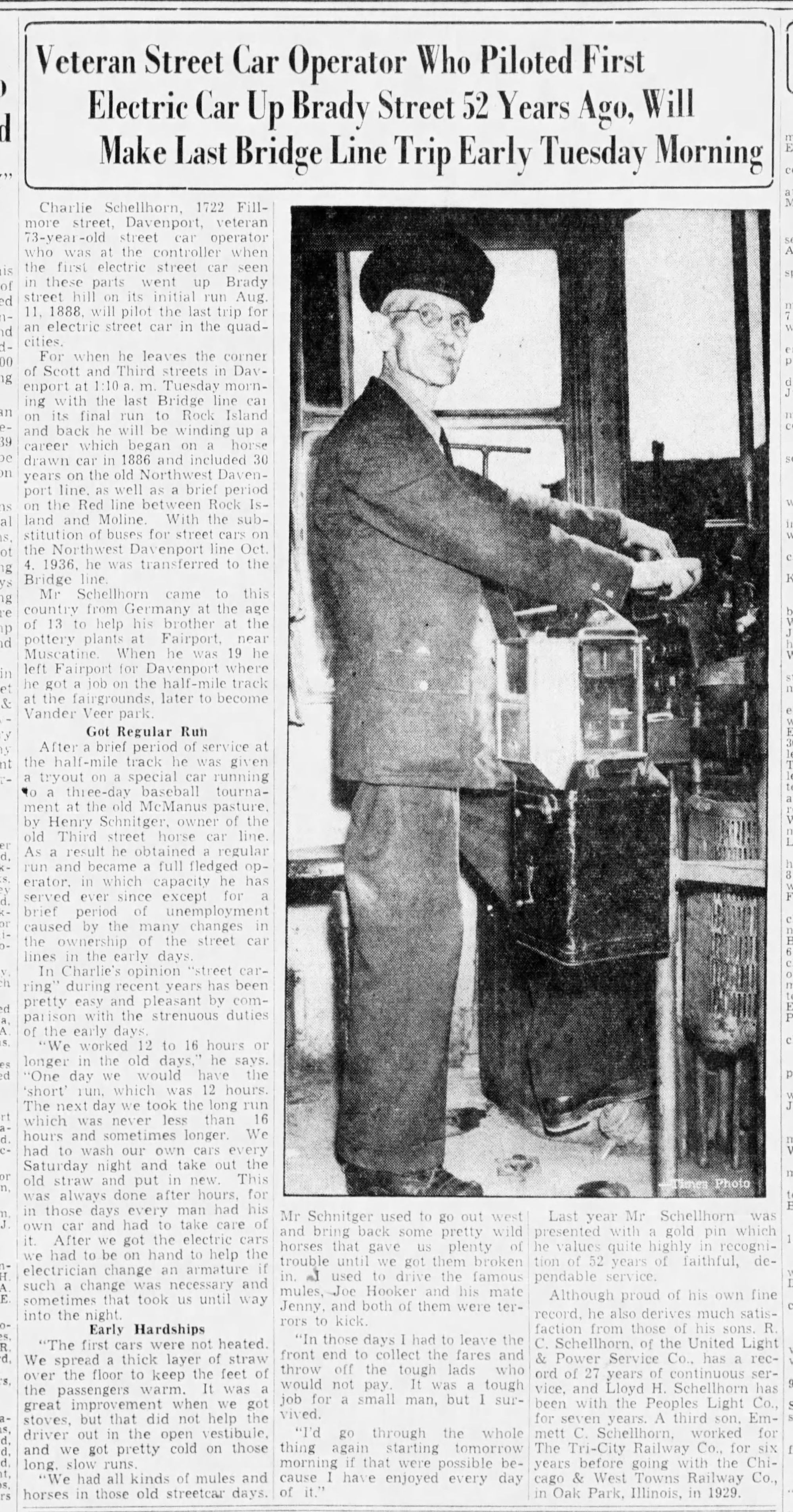

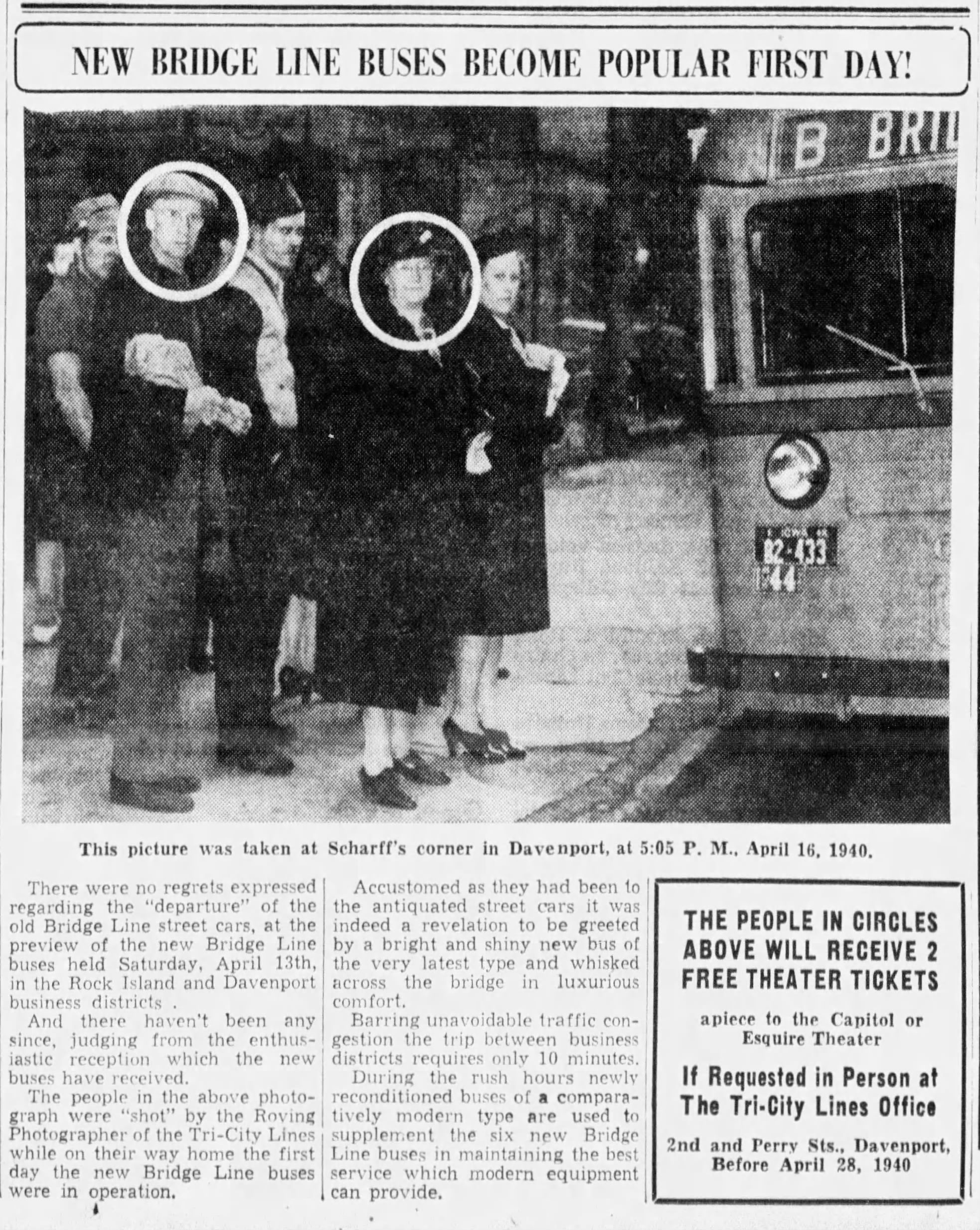

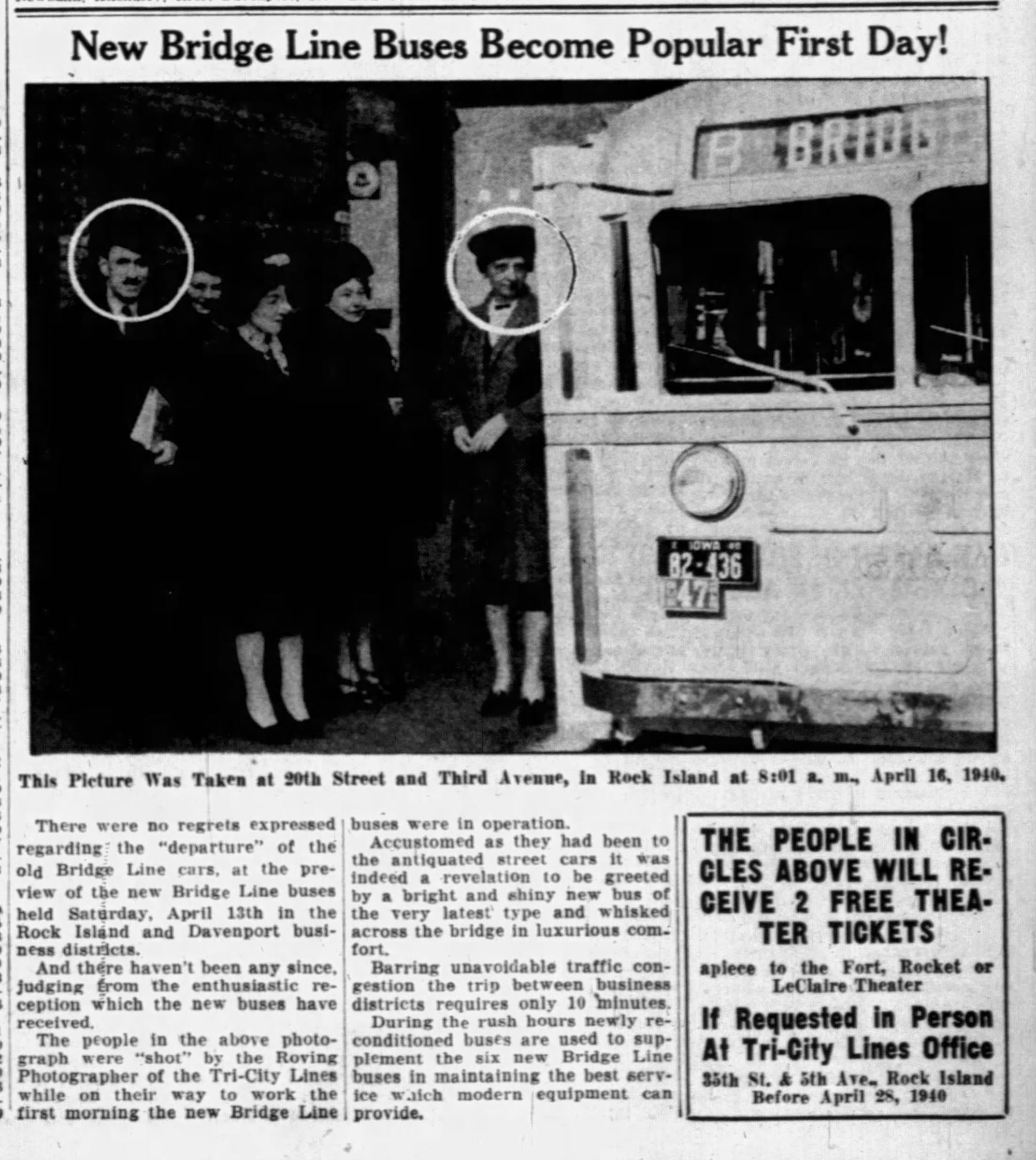

The most obvious one is the streetcar–the Bridge Line was the last Tri-City (...yeah, Tri) Railway Co. streetcar to switch to buses when service ended in April 1940. That little bridgehouse with the red roof is also gone, but otherwise the steel truss superstructure of the bridge is unchanged and the Rock Island Arsenal’s Clocktower Building still looms over the south bank of the Mississippi River (remember, it flows east-west here).

This Government Bridge is the continuation of quite a legacy–in 1856, the Government Bridge’s predecessor first linked the agricultural hinterlands of the Great Plains to Chicago by rail. This reshaped the entire ecology, economy, and landscape of the Midwest, turning it into the industrial agriculture engine feeding the growth of Chicago (read Nature's Metropolis). Once railroads began to crisscross the country, a rail bridge crossing the Mississippi River was inevitable, but still–the first one, in all of the United States, was here, connecting Rock Island, Illinois and Davenport, Iowa.

Well, here…ish–the Government Bridge’s great-great-grandfather (grandbridge?) was located a few hundred yards upriver. Mississippi River shipping, already opposed to the construction of railroad bridges that threatened their market share, argued it was dangerously sited, a navigational hazard. And lo–only a few weeks after the first bridge’s completion in 1856, the steamer Effie Afton struck the bridge, caught fire, and sank. The steamship companies sued to have the bridge removed, but lawyer Abraham Lincoln (yeah, same one) fought them to a successful draw in Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Co. The bridge stayed, and the door remained open for more bridges to cross the Mississippi (the Supreme Court affirmatively decided so in 1862).

Funny thing—the steamship companies were probably correct. Narrow, with a strong current, and oddly angled, this was a poor location for a bridge. Of the 1,667 boats that passed the bridge in 1857, 55 hit it, and it struggled with damage from ice. So they…doubled down, building a reinforced bridge on the same footprint in 1866–the Second Bridge. It wasn’t just inconvenient for river traffic, though–it also split the growing US Army presence on the island in two. Only six years later, pushed by the federal government, the railroad finally gave up on this location. Bridge #3, moved 1500 feet downriver, opened in 1872. Also double-decked, with rail above and everyone else below, the third bridge was very much the model for today’s Government Bridge.

…with one major issue–the rail line was single-tracked! Skyrocketing rail traffic (which was also growing heavier and heavier) and the continuing need to swing open for river traffic soon turned the third bridge into a major bottleneck, so in 1895 the federal government authorized the construction of a fourth bridge here.

A joint venture between the US Army and the Chicago, Pacific & Rock Island Railroad, they hired engineer Ralph Modjeski to build the new Government Bridge. Born in Poland, raised in the US, and educated in France, Modjeski was the son of Helena Modjeska, one of the greatest actors in Polish history (man, math and drama–get you a family that can do both). Helena’s son would leverage his success here into a long, influential career designing steel truss and–later–suspension bridges across the US. There are still a bunch of Modjeski-designed steel truss bridges that cross the Mississippi River, but his most famous commission is probably the massive Benjamin Franklin Bridge in Philadelphia. He also consulted on the Ambassador Bridge in Detroit, the Manhattan Bridge in New York, and the Bay Bridge in San Francisco.

The fourth Government Bridge had three requirements: better handle the frequency and weight of freight rail operations, maintain efficient and safe passage for river traffic, and enable street access from Davenport to the Rock Island Arsenal, which by the 1890s had become a major manufacturer of weapons and military equipment for the US Army.

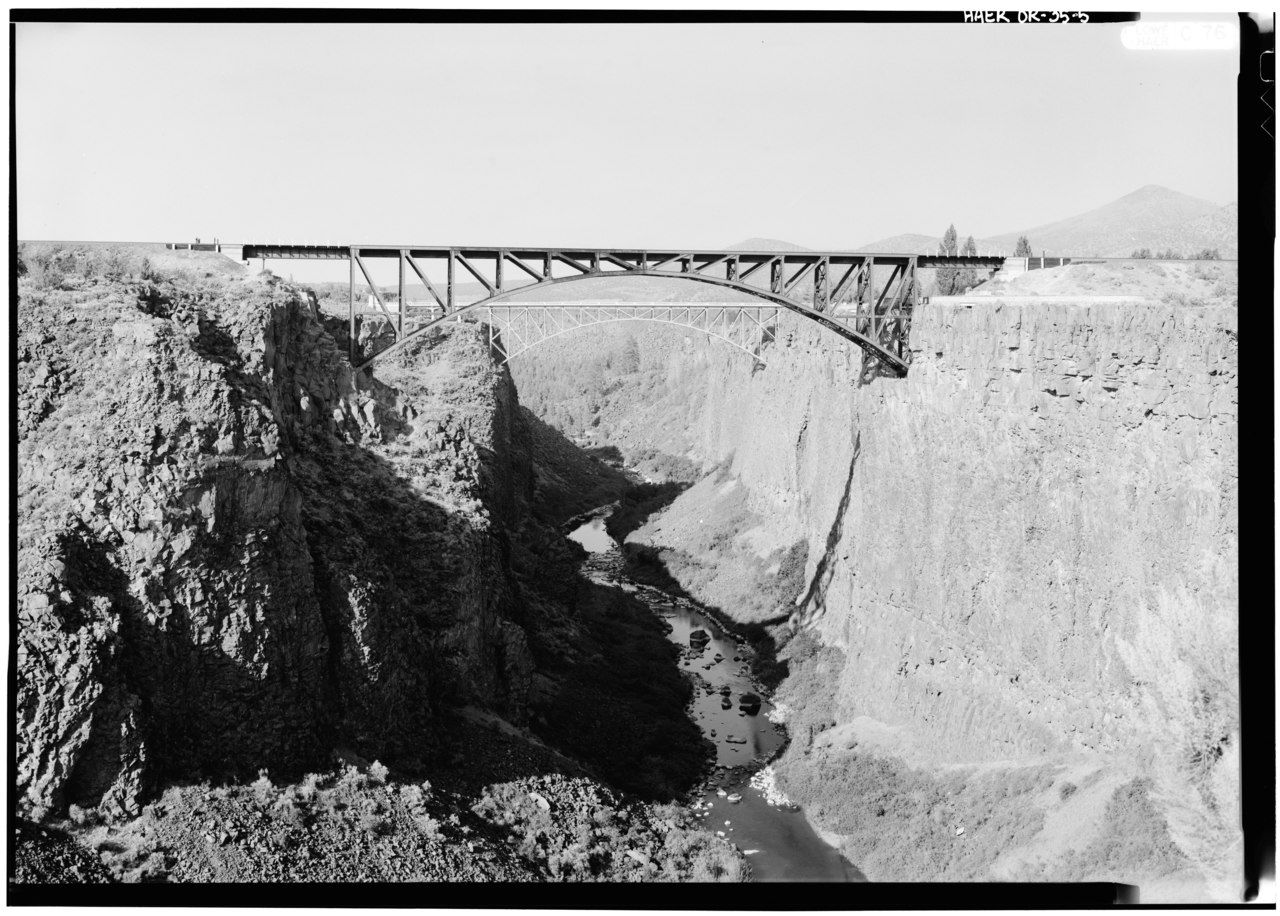

To meet those objectives, the Government Bridge was simultaneously over-engineered and thrifty. To save time, money, and limit disruption, the new bridge was built upon the piers of the third bridge. It’s also one of the only swing bridges in the world that can rotate 360 degrees in either direction, ostensibly to help deal with changes in wind (the swing span once ended up freewheeling after an accident, and it rotated a full 15 times before it was stopped by its own gravity). The superstructure is so robust that a 2019 fatigue study– performed, incredibly, by the same firm who built the bridge, Modjeski & Masters–found that the bridge had only used a small portion of its serviceable life. Gotta appreciate an unnecessarily brawny late 1800s bridge.

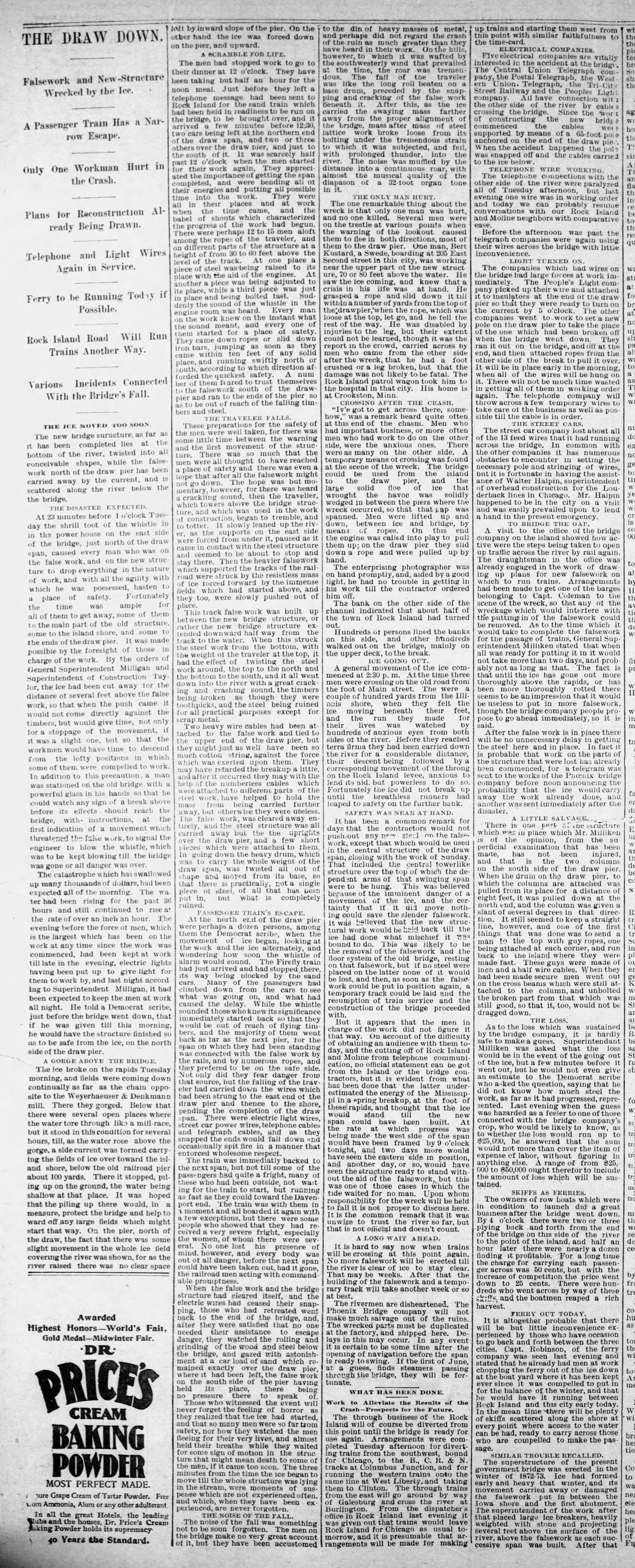

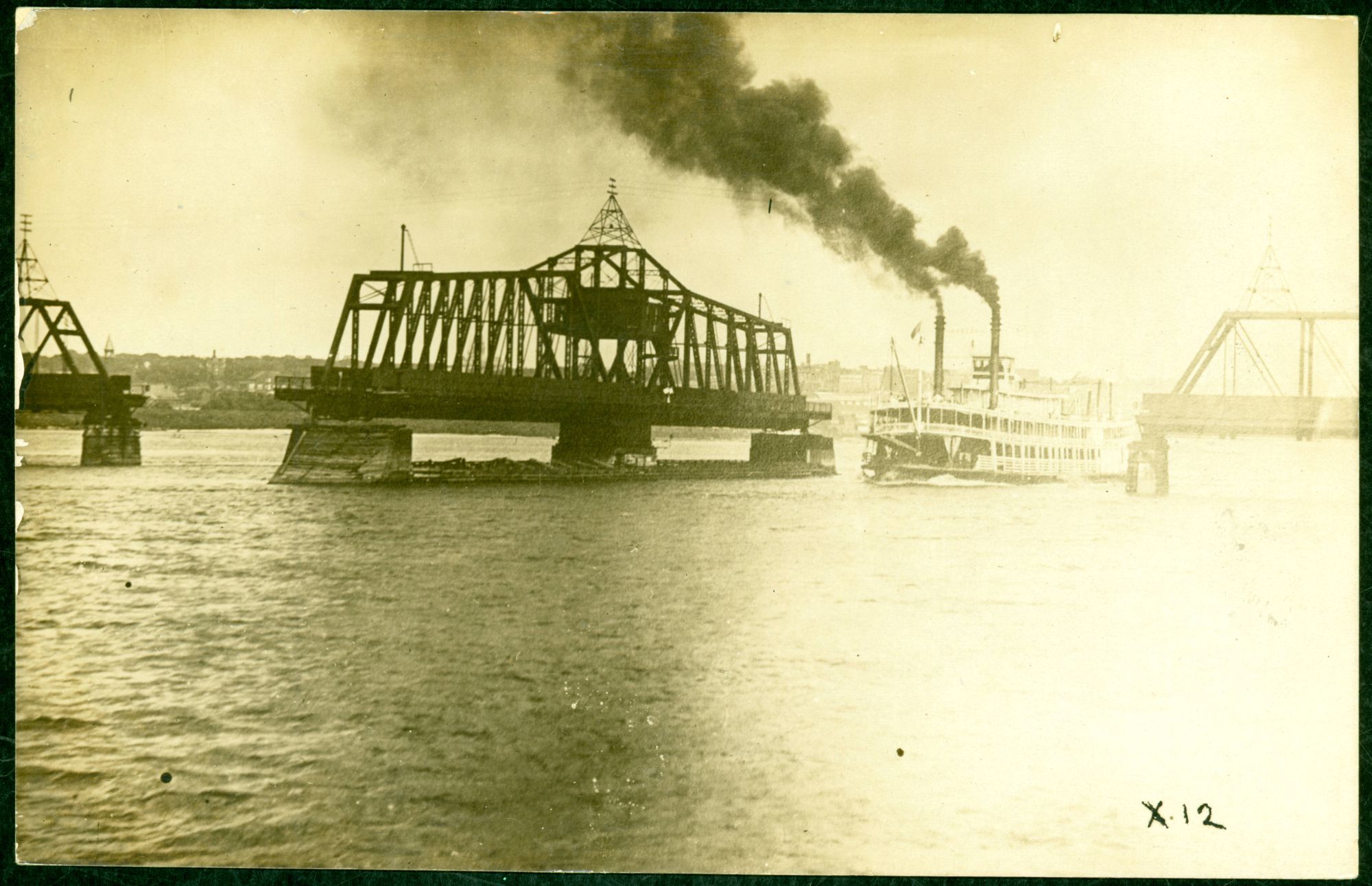

Construction didn't exactly go to plan. Satisfying both rail and river traffic required threading a needle: to avoid disrupting shipping, they limited construction to the winter months when the river was closed to traffic, and for rail’s sake, they replaced one span at a time. Unfortunately, there were delays in the delivery of steel, so in late February 1896 the swing span and its railroad track was still held up by falsework–no biggie, so long as the river stayed frozen (spoiler, it didn’t). Workers raced to finish the installation of the steel swing span as temperatures rose, but they didn’t make it. Melting ice floes traveled down the river, and the resulting ice jam destroyed the falsework, sending the steel span into the Mississippi. Remarkably, it only disrupted rail traffic for a month and they fished out the steel before the river reopened to shipping traffic.

Shortly after it opened, in 1898, an average of 5,000 people a day crossed the bridge via streetcar (190 streetcar trips), horse-drawn vehicles (about 1,200 teams), and by foot (more than 3,200). By 1949, with the widespread adoption of cars and the junking of the streetcar, those numbers were quite different. 17,300 cars and 55 trains crossed the bridge per day, which also opened three times a day on average.

Quick aside on the streetcar–of course, like most Midwestern urban areas, the Quad Cities used to have a robust streetcar system. And yeah, apparently the Quad Cities used to be known as the Tri-Cities–the area was renamed the Quad Cities in the 1960s, when they decided East Moline was big enough to count (...and of course, with Bettendorf, there are now five Quad Cities). Streetcars from the Tri-City Railway Co. first crossed the third Government Bridge in 1888. The Tri-City Lines swapped out most of their streetcars for buses in 1936, with the Bridge Line streetcar surviving until April, 1940.

Back to the Government Bridge itself–the span we have today hasn’t changed too much since then. The piers it stands on were encased in concrete in the early 1920s and the nearby construction of Lock and Dam 15 in the 1930s raised the mean water level under the bridge by 16 feet. Modjeski and Masters have performed a few rehab and restoration projects on it, most notably in the 1950s and the 2010s. But the bridge mostly just continues to…bridge. Still owned by the US Army, after the bankruptcy of the Rock Island Line the track is now leased by the Class II Iowa Interstate Railroad. Only the upriver track is currently in use, but roughly 4-6 trains a day still cross the bridge, and the swing span opens a few thousand times per year to accommodate shipping traffic. The Government Bridge is also included as a contributing structure in the NRHP-listed Rock Island Arsenal National Historic District.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Nature's Metropolis by William Cronon

- From the historic bridge community: Historic Bridges, John A. Weeks III, John Marvig

- A timeline and an update on their latest work on the bridge, from the firm that built the bridge, Modjeski & Masters

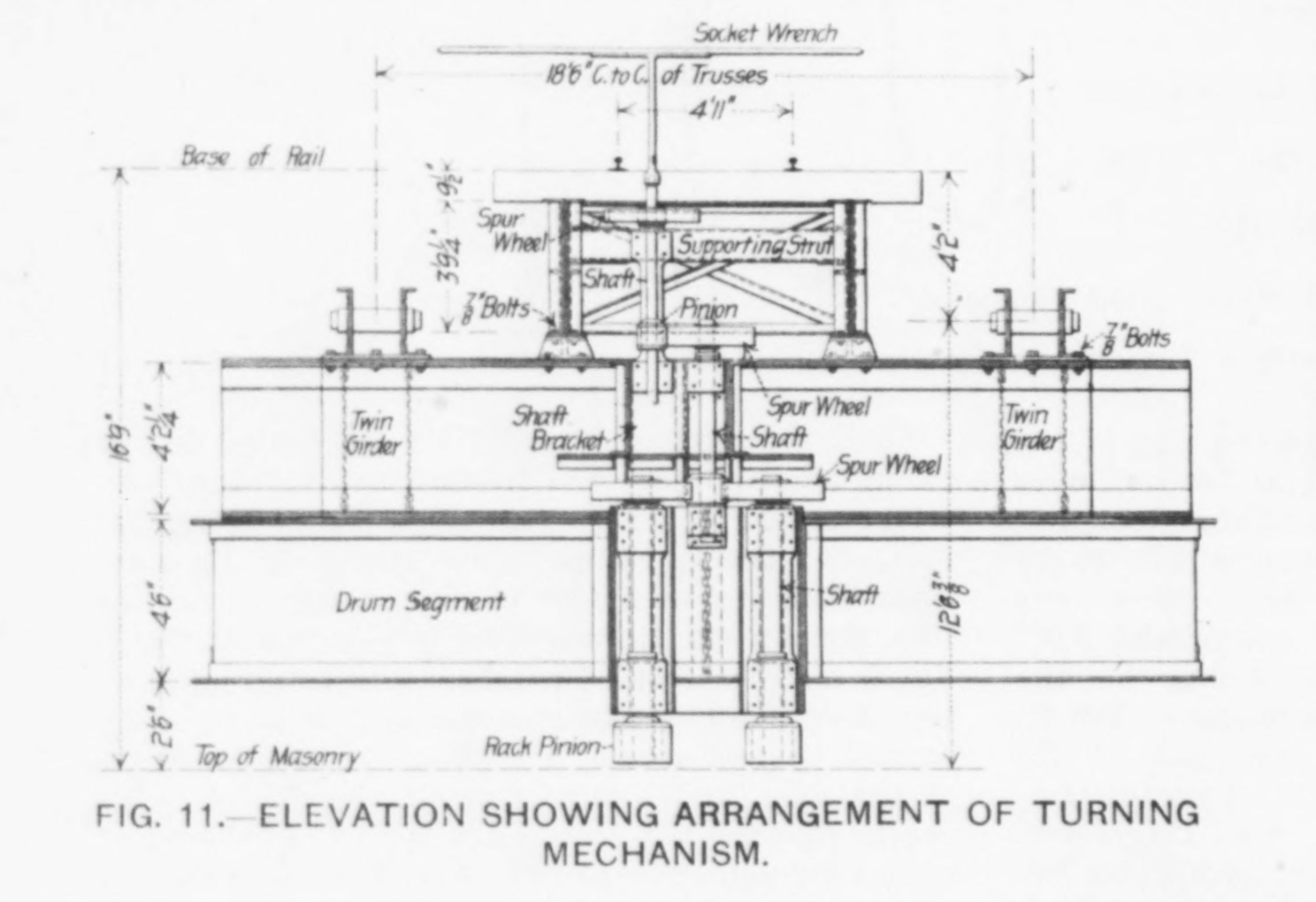

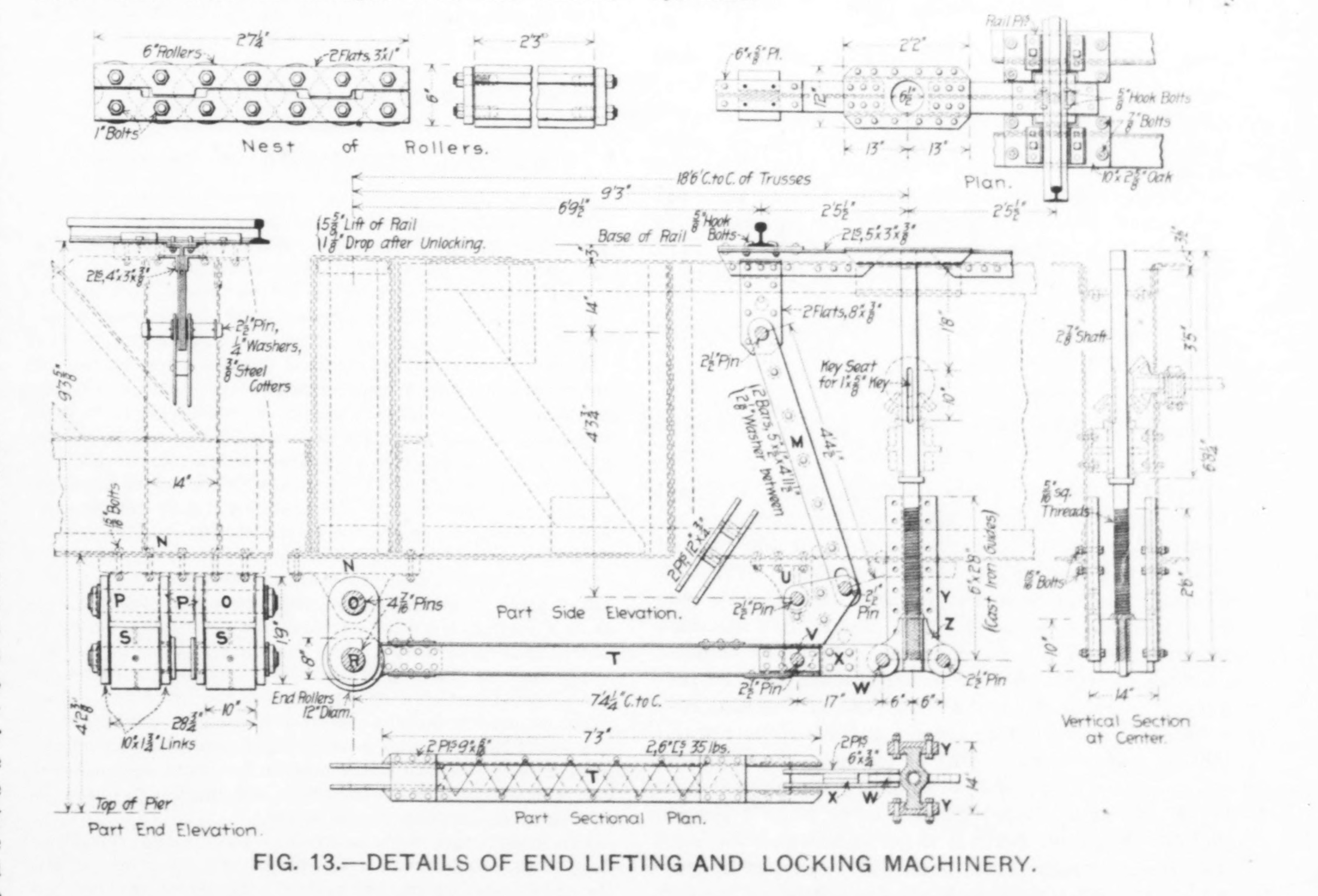

- A real in-the-weeds engineering look at the bridge from 1900

- "One Hundred Years of the Rock Island Government Bridge" in the Journal of Bridge Engineering, 1997

- A very long bio on Ralph Modjeski from 1944

- A blog post from the always-excellent Rock Island Preservation Society

- A look at all four bridges from the US Army Corps of Engineers

- More on the Quad Cities former streetcar system: the Davenport Public Library, Hicks Car Works, and the Great Electric Streetcar Company and Other Stories, by James F. Lardner

Member discussion: