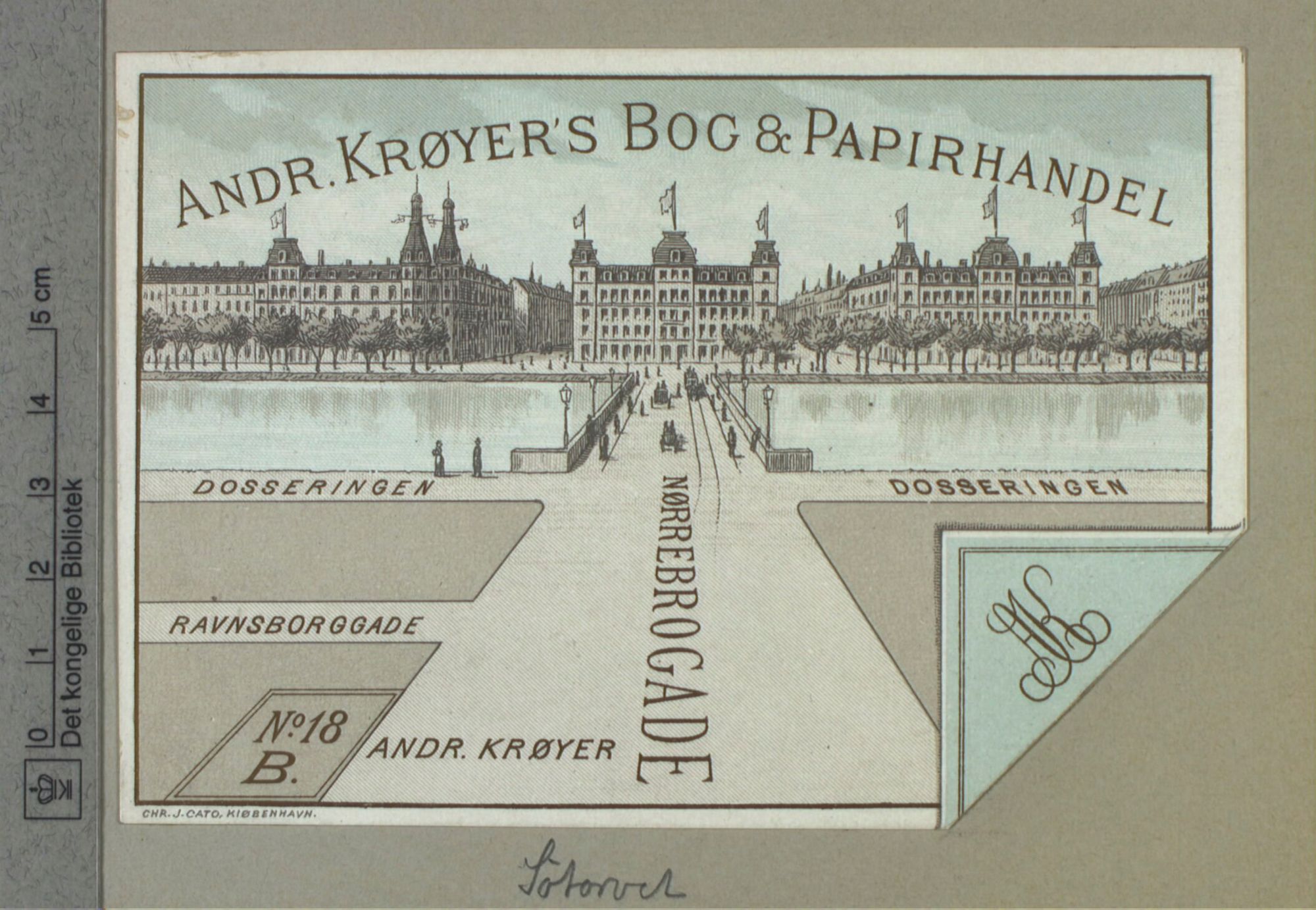

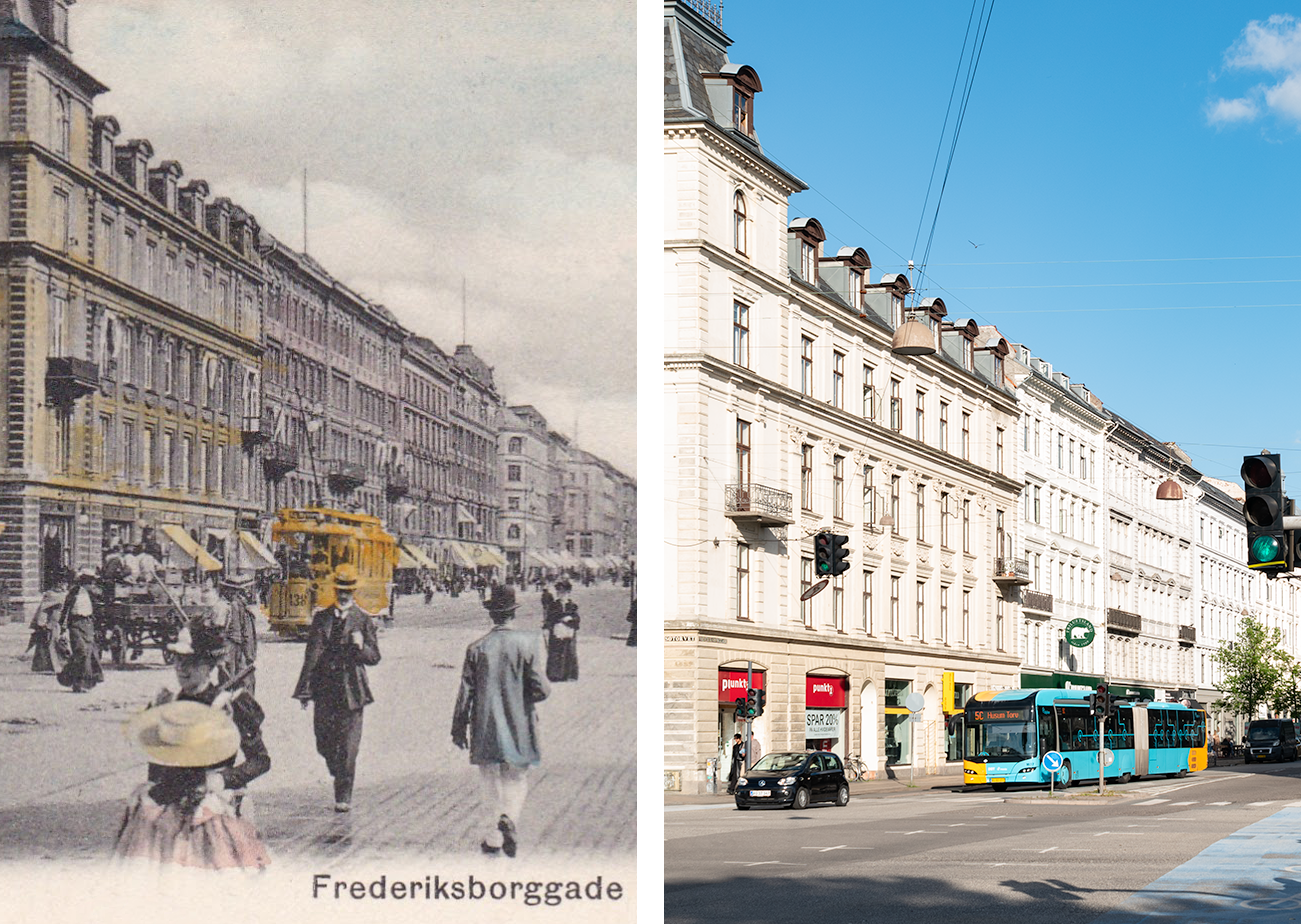

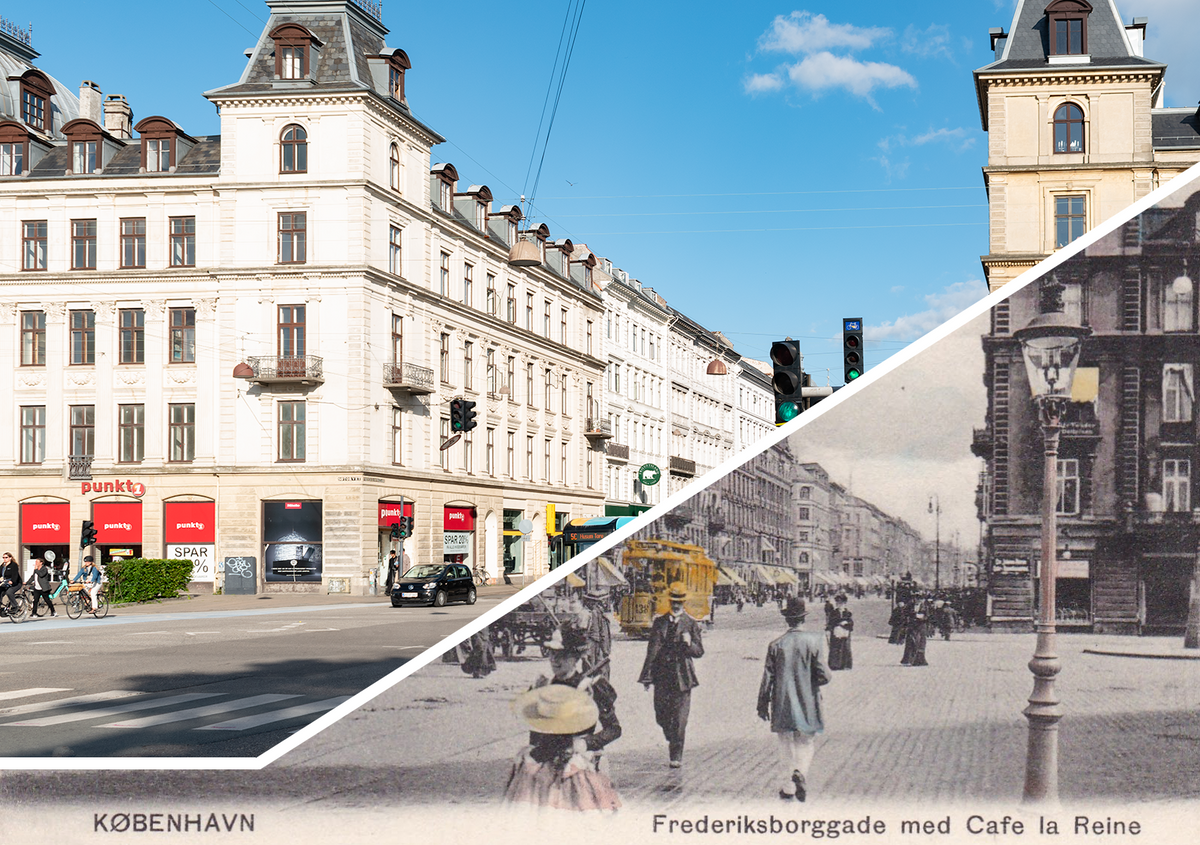

Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s renovation of Paris directly inspired Ferdinand Meldahl’s plans for Søtorvet, a four building development envisioned as a grand new northern gateway to central Copenhagen. Completed in 1875, architects Ferdinand Jensen and Vilhelm Petersen designed Søtorvet under Meldahl’s direction. While the buildings of Søtorvet are remarkably preserved, Line 7 of the Copenhagen tram system was replaced by buses in 1971.

Unlike Haussmann’s Paris, though, this one was built without mass demolitions–once the city fortifications around Copenhagen were decommissioned in the 1860s, a vast frontier of lightly built land opened for development. Søtorvet, developed by the Kjøbenhavnske Byggeselskab joined the new neighborhoods that sprouted outside of old Copenhagen. The Kjøbenhavnske Byggeselskab, politically connected, backed by some of the richest old men in Denmark, and with Ferdinand Meldahl managing their construction projects, also built the Hotel D’Angleterre and the area around Hovedvagtsgade on Kongens Nytorv.

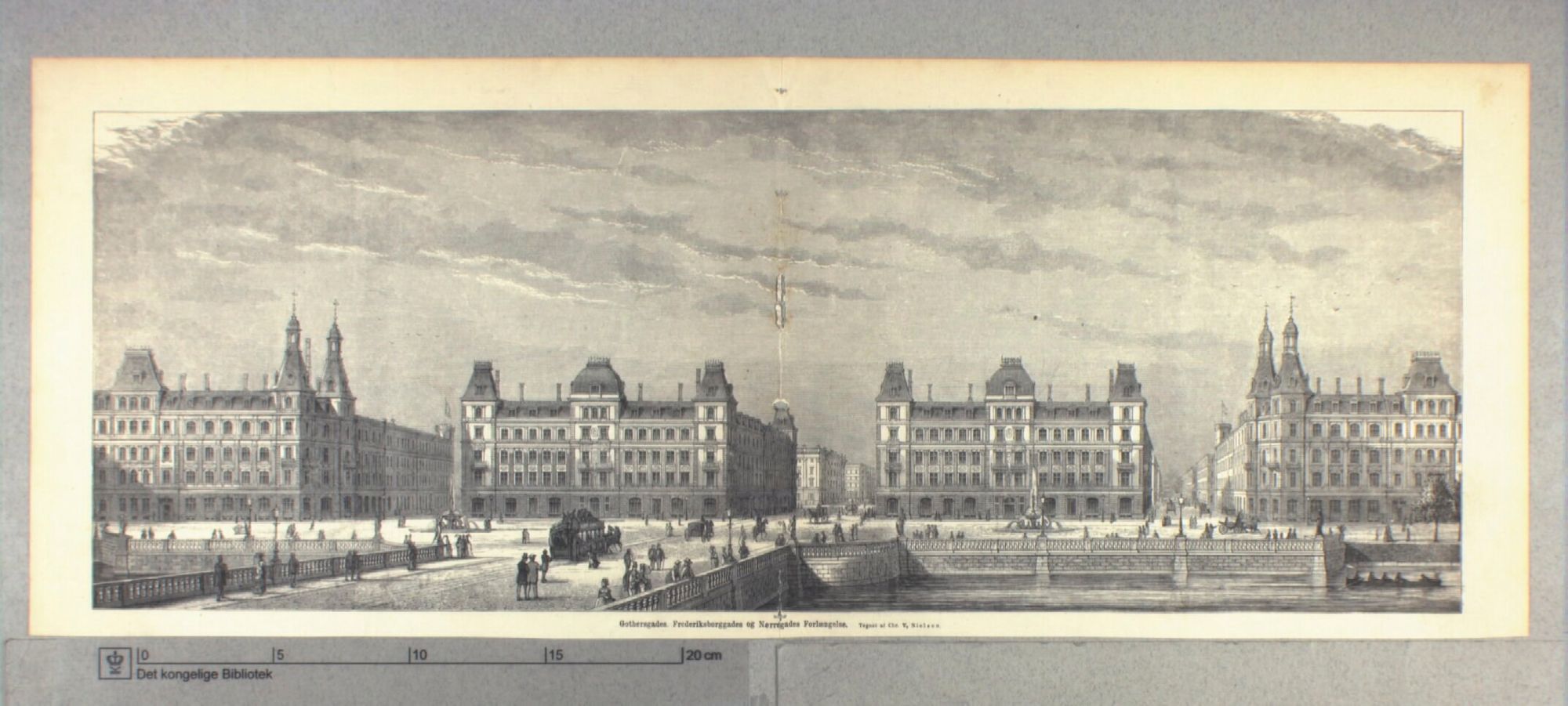

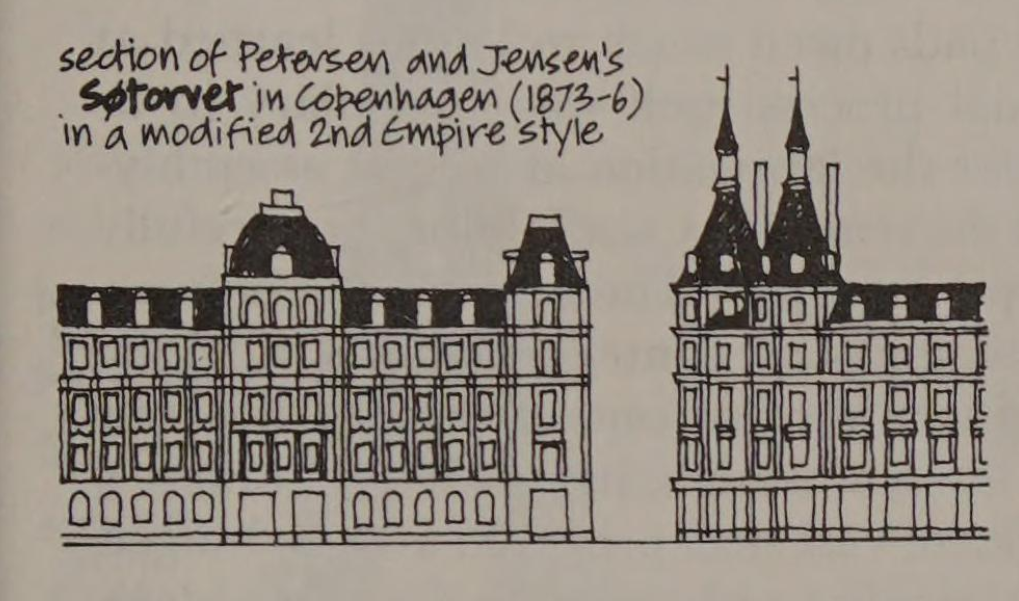

Meldahl, the high priest of architectural conservatism in Denmark in the late 1800s, spent some time in Napoleon III’s France in the 1850s. Søtorvet is clearly loving a historicist ode to that Paris–and so faithful that the building code had to be changed to accommodate the steep mansard roof (I’m not saying the politically-connected developer used their pull to change the building code just for that…but I’m not not saying that either). The two innermost buildings would be twins, flanked by matching outer apartment blocks, split by Frederiksborggade down the center, to create a satisfyingly symmetrical portal to Copenhagen.

While Ferdinand Meldahl set out the broad outlines for the project, it was Ferdinand Vilhelm Jensen and Vilhelm Petersen who actually designed the four neo-renaissance buildings that make up Søtorvet. Neither architect was especially consequential, to be honest. Jensen probably has more work still standing, mostly in the form of pleasantly forgettable apartment blocks–cityscape filler that’s important collectively but unremarkable individually. Vilhelm Petersen’s wikipedia page is pretty funny, describing him as “not particularly outstanding in practical terms” and castigating his “brutal restoration of Brønshøj Kirke” (...and not the good kind of Brutal).

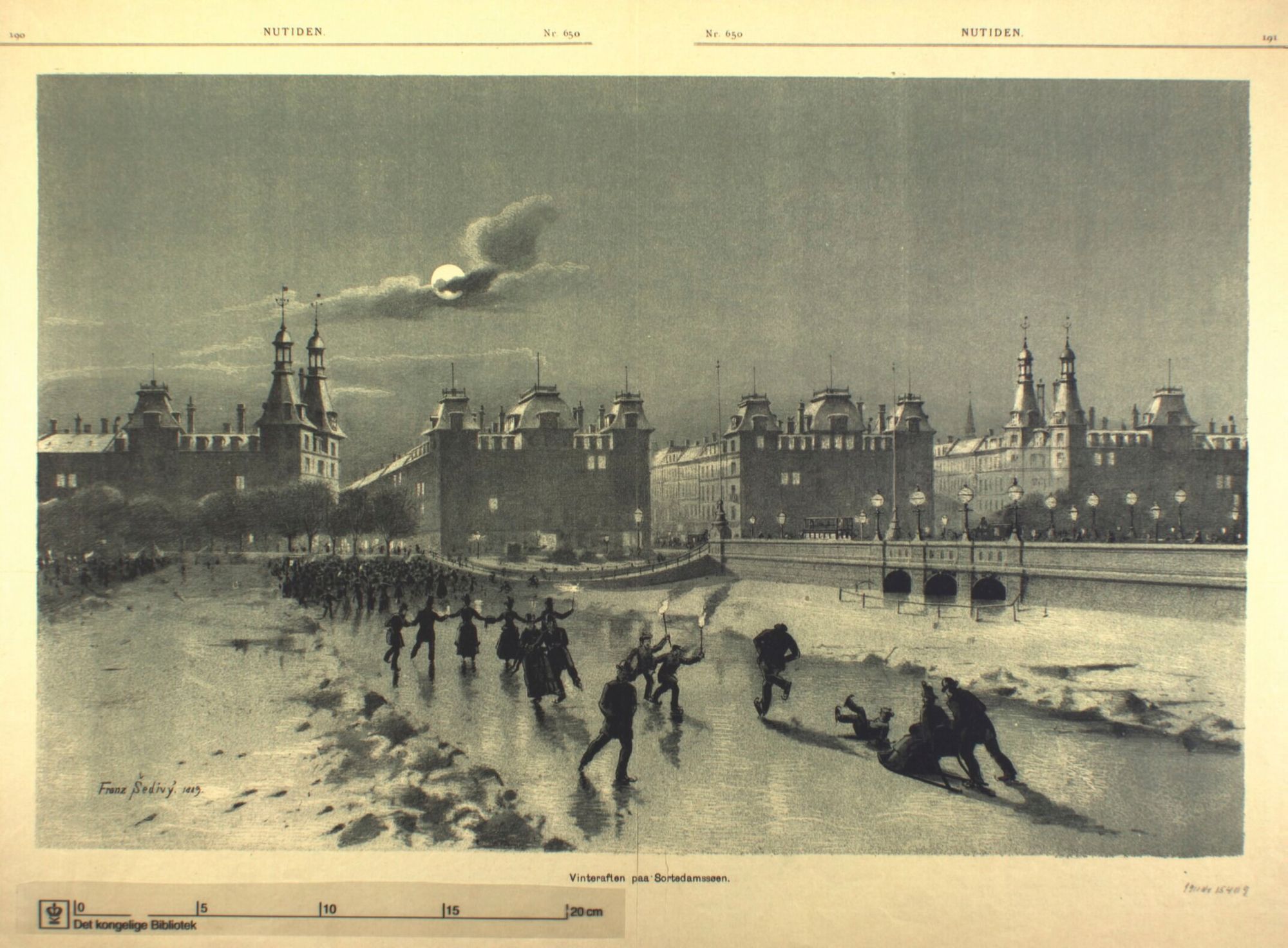

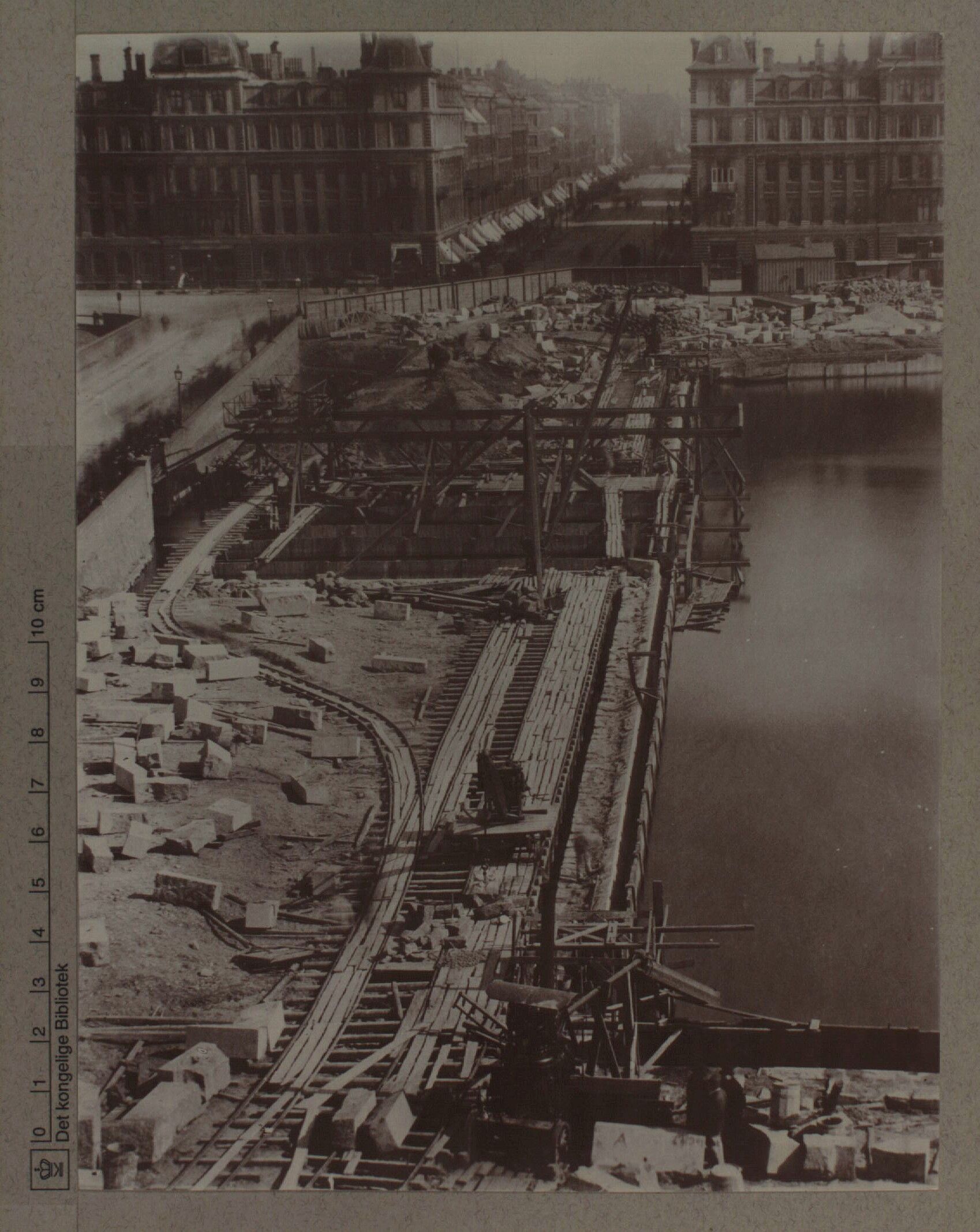

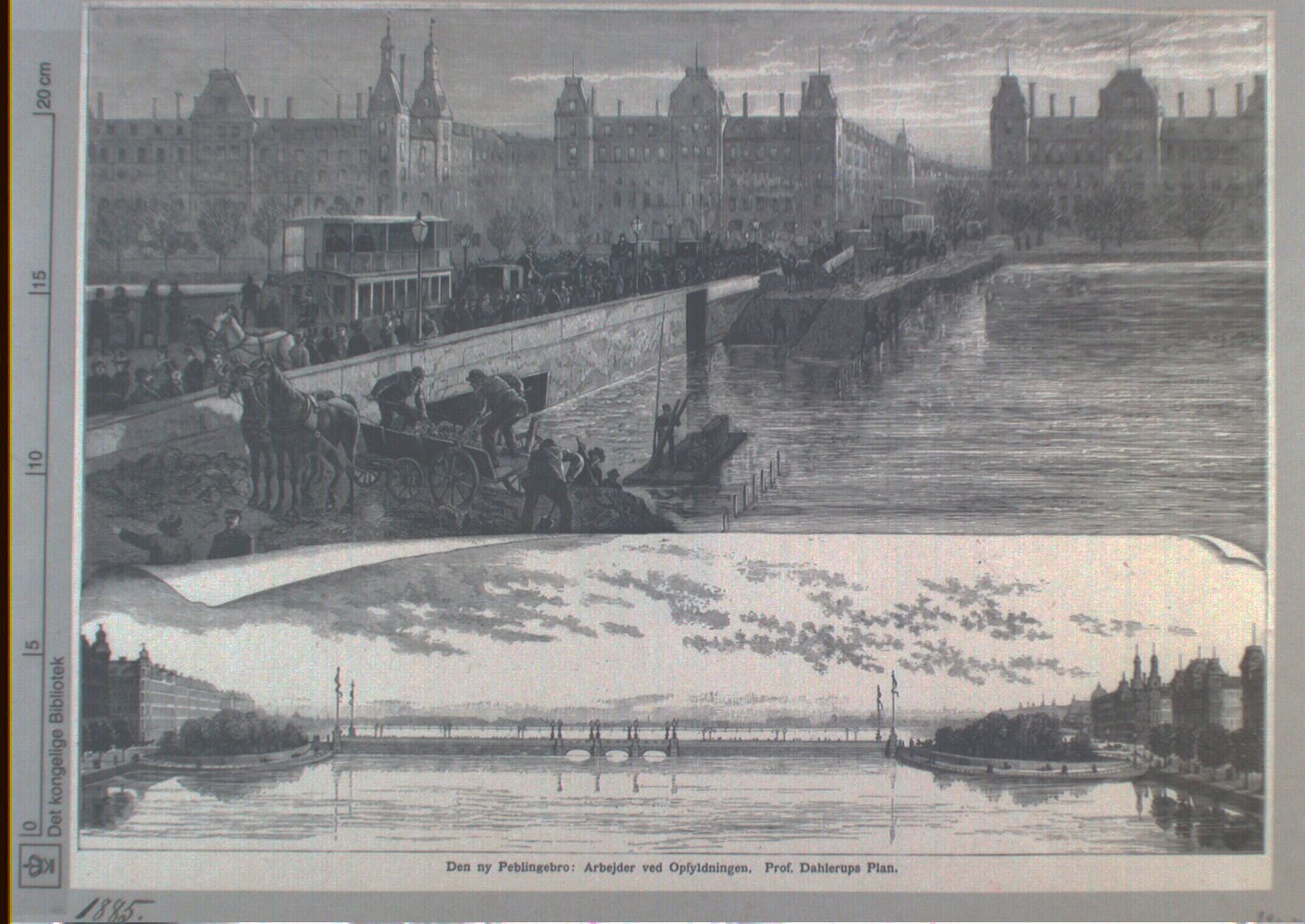

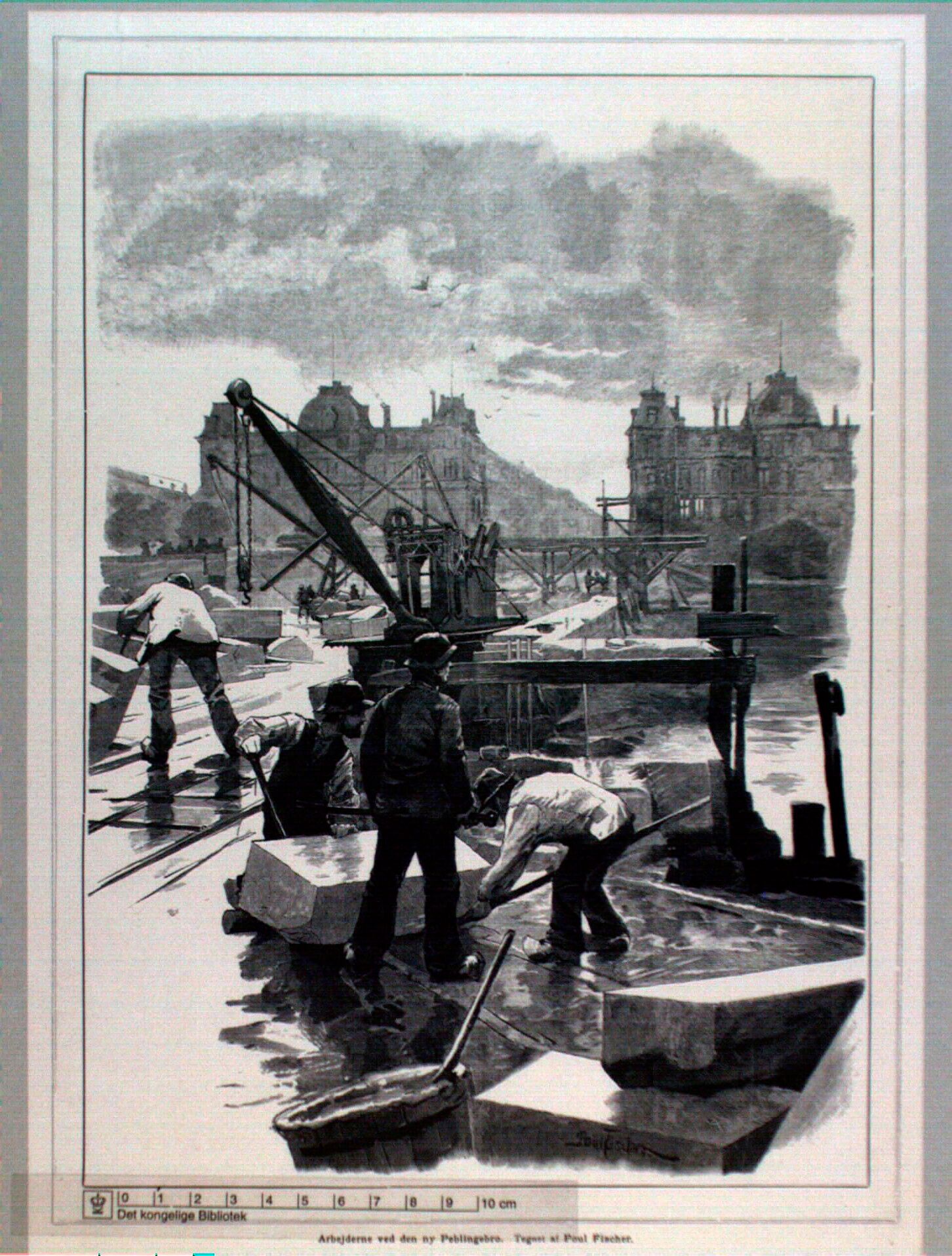

Surprisingly (to me, at least), Søtorvet predates the bridge that makes it such a geometrically-striking entrance into the city–Dronning Louises Bro only opened in 1887. There was a bridge that crossed the lakes here when Søtorvet was built, but the Peblingebro crossed at an angle, which just looks wrong, like someone made a mistake (on second thought, the alignment of the old Peblingebroe looks a bit like the much-maligned Inderhavnsbroen).

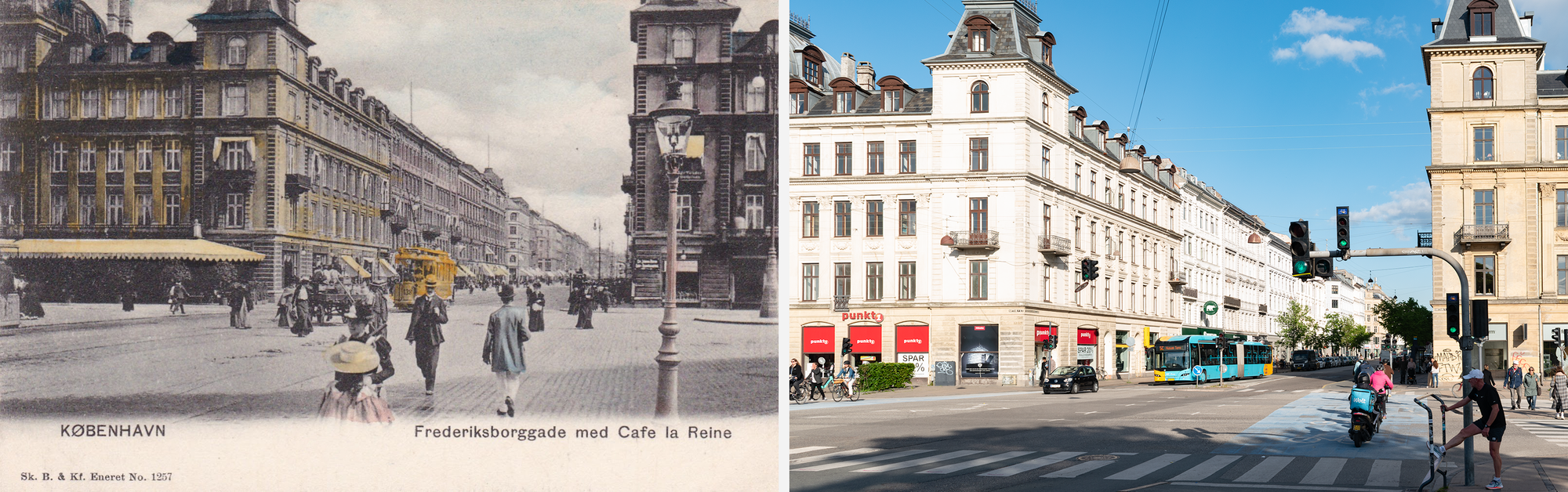

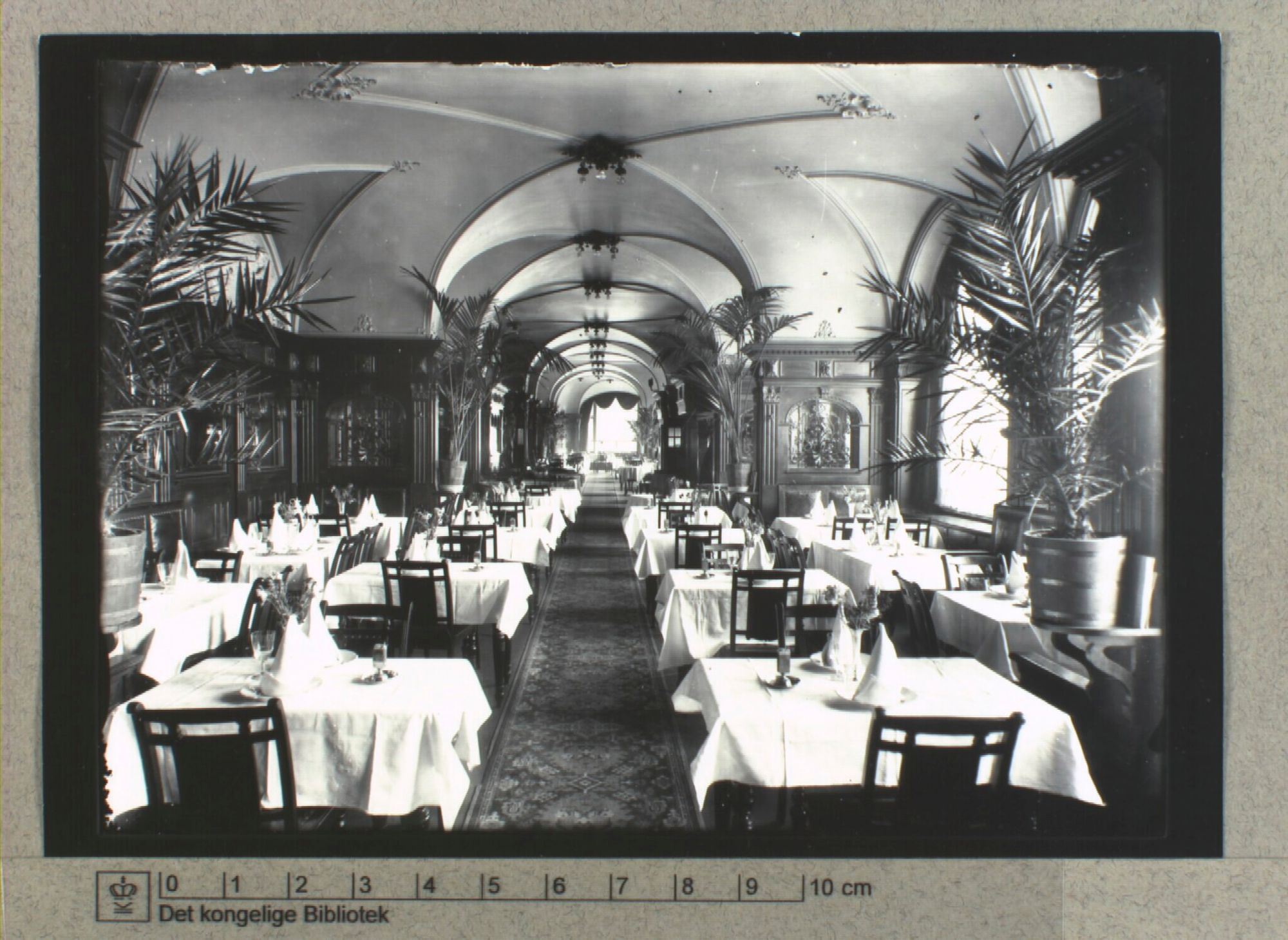

If it were built today, we’d describe Søtorvet as a mixed-use luxury development, with commercial on the ground floor and apartments above. Its most renowned commercial tenant was Café de la Reine, a French-inspired cafe for a French-inspired building. Open from 1901 until 1940, Café de la Reine was popular with a well-off bohemian-adjacent crowd and hosted live music almost every day. Today it’s an appliance store.

The 7 tram is visible in the postcard. Copenhagen doesn’t have streetcars anymore–the 7 was one of the last tram lines, replaced by a bus in 1971–but you’ll soon be able to hop on a tram near Copenhagen. A suburban light rail line running between Lyngby and Ishøj will open in 2025.

The 7 is a decent stand-in for the story of the whole Copenhagen streetcar network. Opened in 1867 as a horse car line, it was converted into an electric streetcar in 1902. Unlike many European cities, Copenhagen tram lines were never separated from car traffic in a serious way–although there was a weird little roundabout here at Søtorvet that let trams drive straight through. The city also underinvested in rolling stock, so for decades the trams were cold, slow, and rickety. They finally bought modern articulated (and heated) trams in 1959, the beloved Duewag Düsseldorf cars, but by that point agency leadership had mentally committed to buses, with conversions beginning in 1962. By ripping up the tram lines, they could add more lanes for cars (god damn it), and as an added bonus buses required less labor to run.

And those new streetcars that Københavns Sporveje bought in the 1960s? 97 of them ended up in Alexandria, Egypt, where they were a workhorse of the fleet into the 2010s.

Production Files

Further reading:

- The conservation listing from the Slots- og Kulturstyrelsen

- A good 2003 article in Berlingske on the building, "The City's Festive Entryway"

- Some cool interior photos from a 2015 restoration by Elgaard – Architecture

- From the building owner, Jeudan

- A Danish bar rediscovered and published the recipe notebook of one of Café de la Reine's bartenders in the 1930s

- Interesting history of the Copenhagen tram system from 1949–1962

- ...and 1962–1972

- "The last tram returned to its depot 50 years ago–was that smart?"

Member discussion: