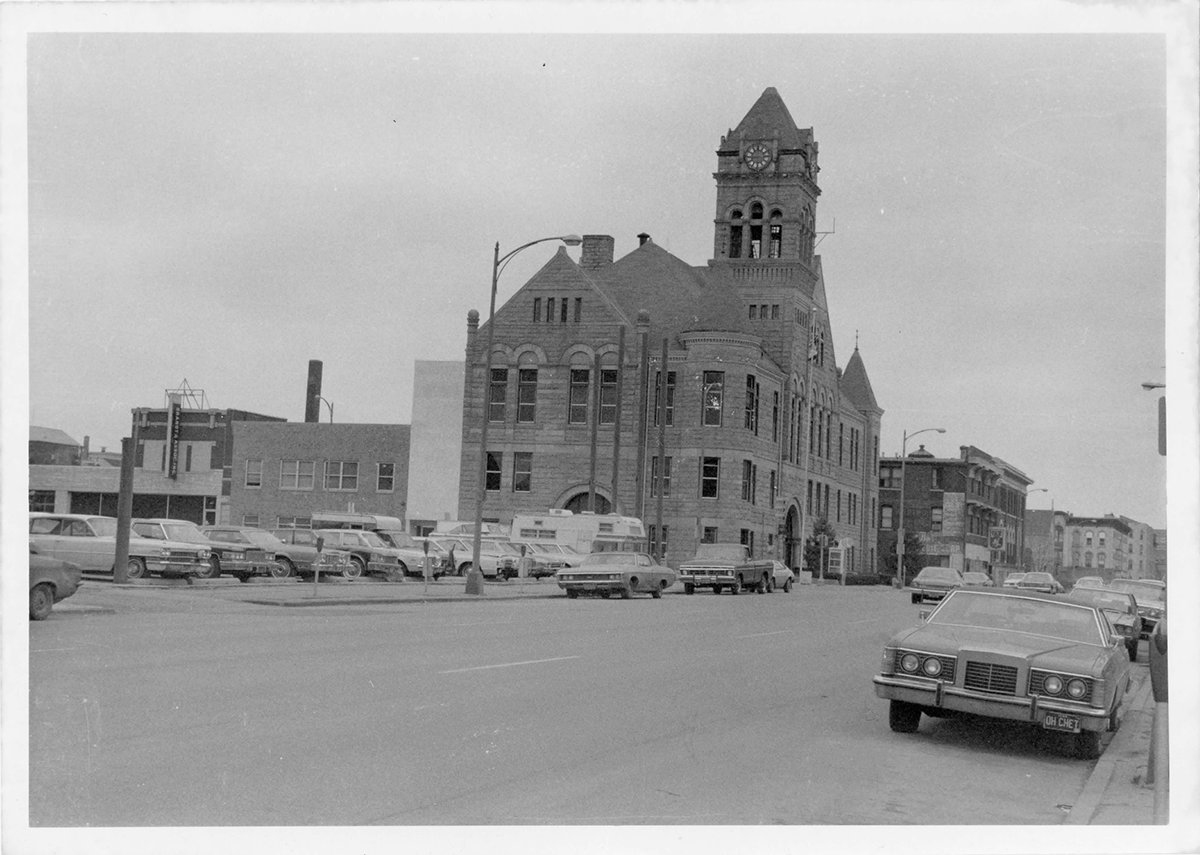

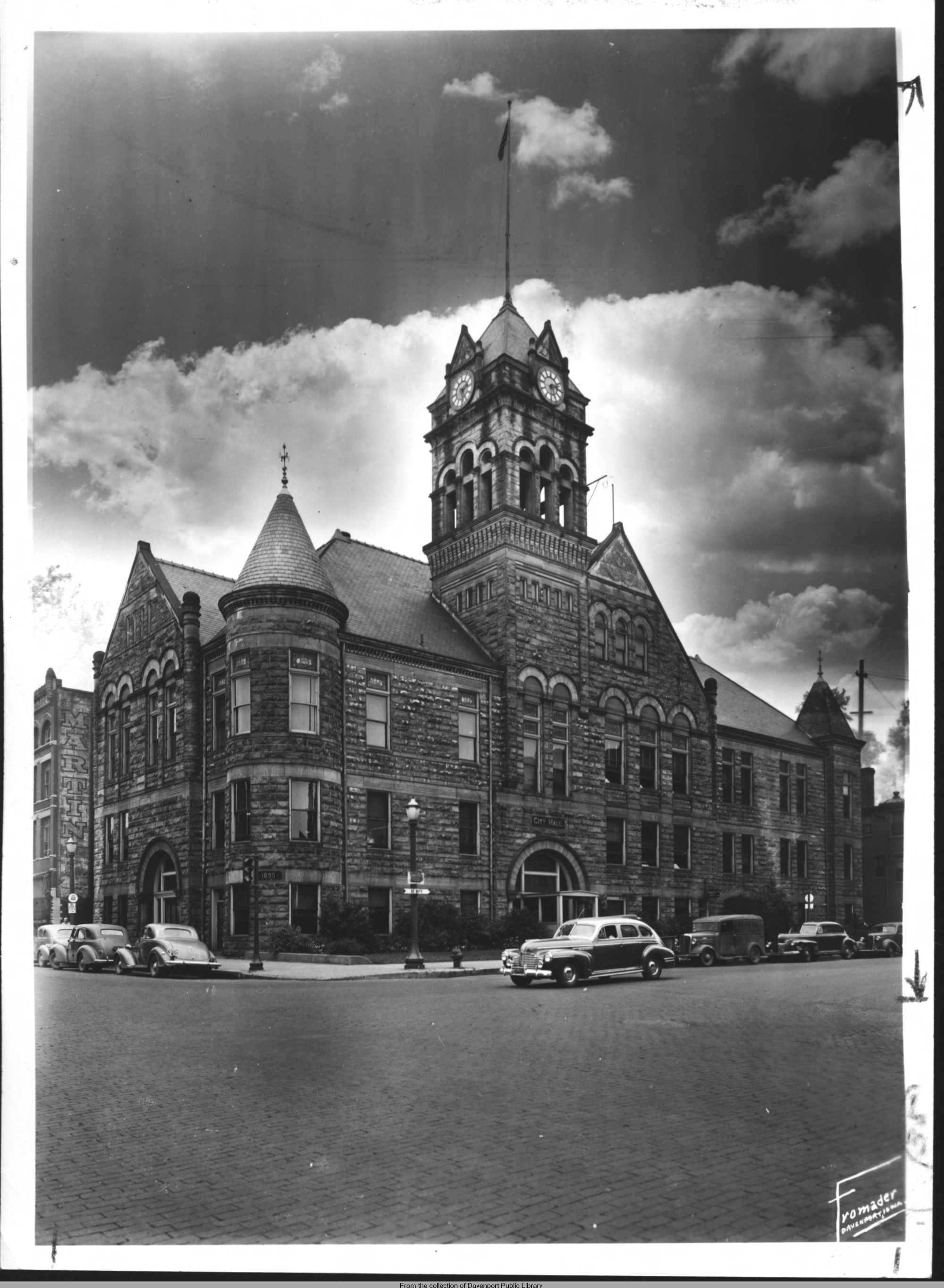

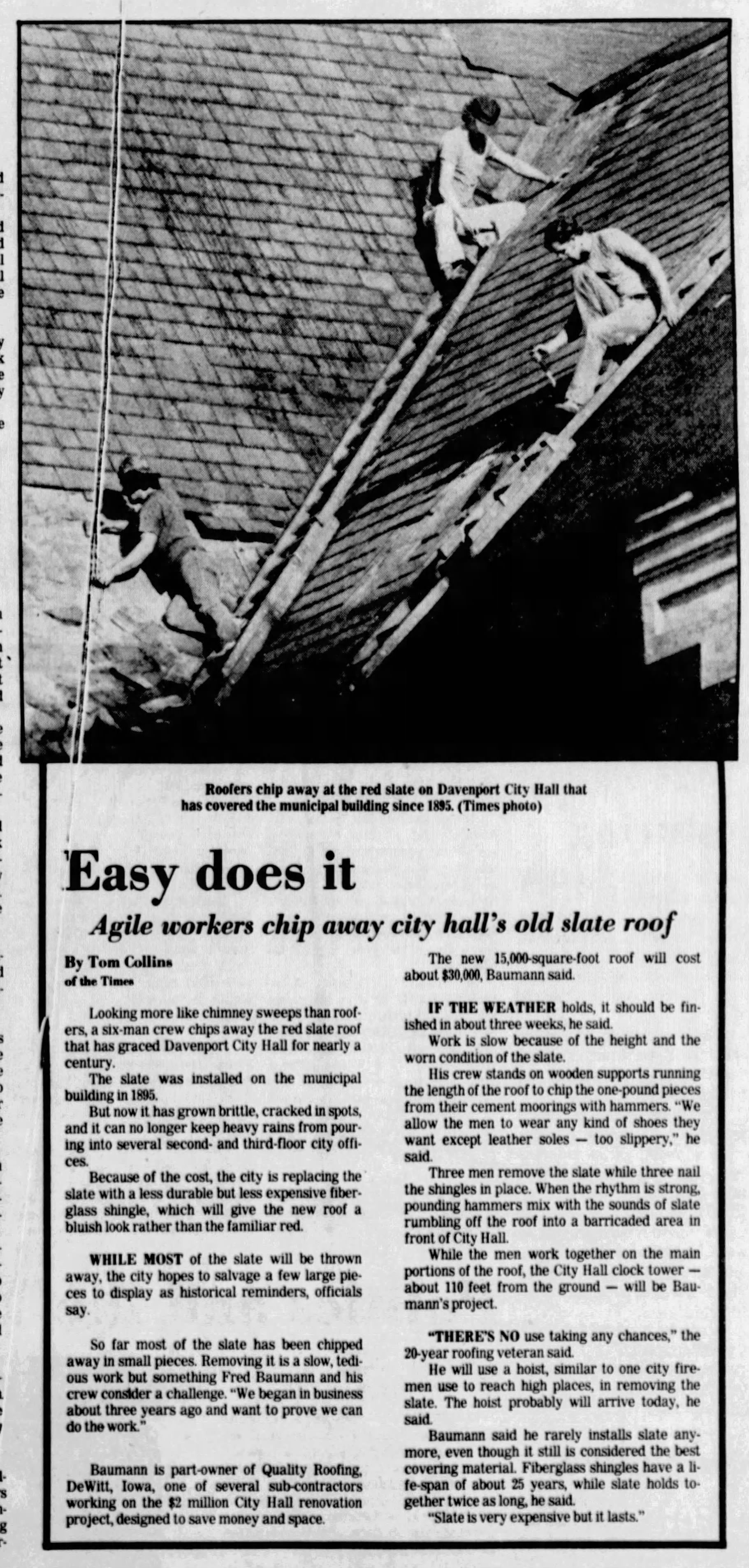

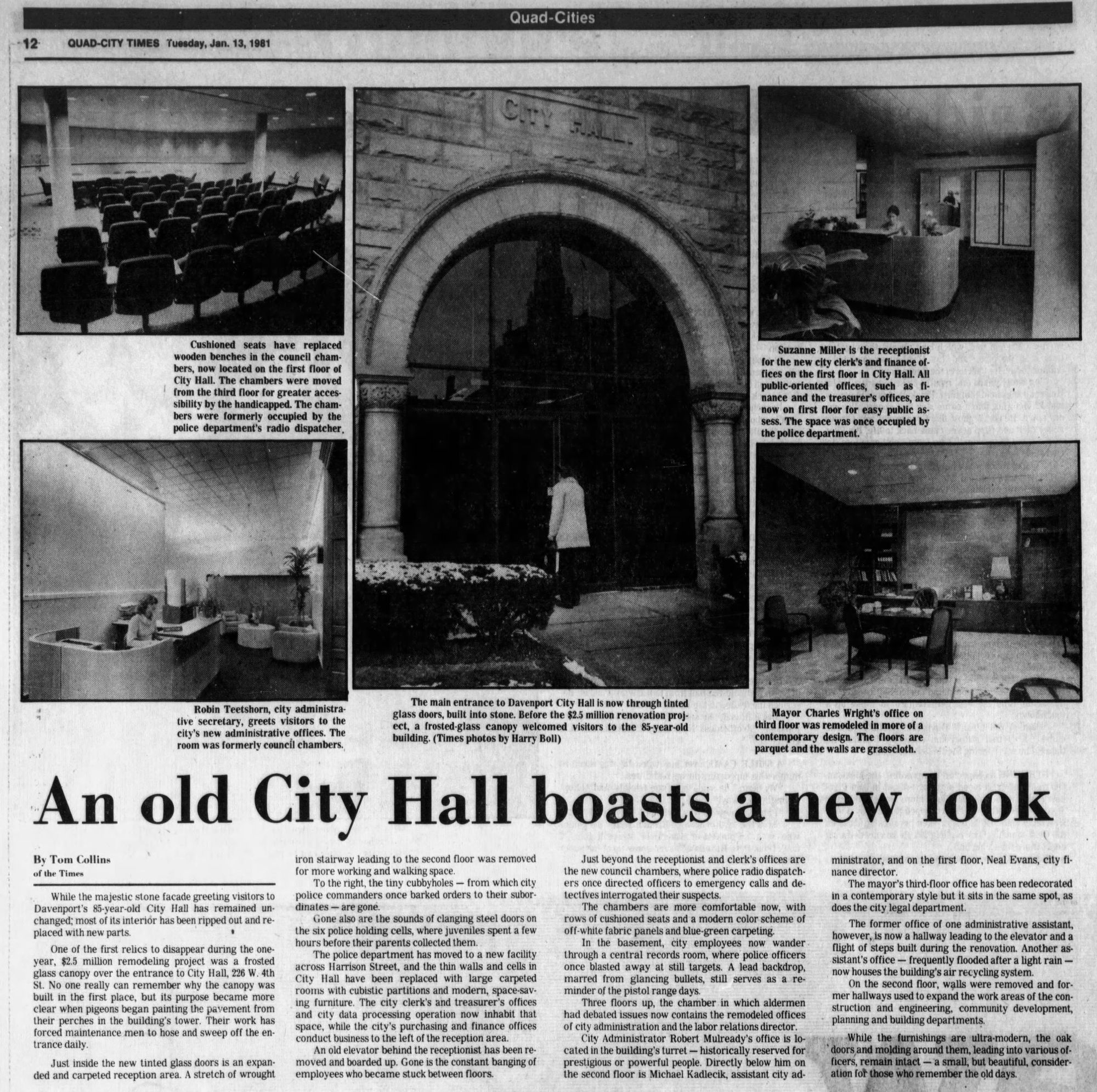

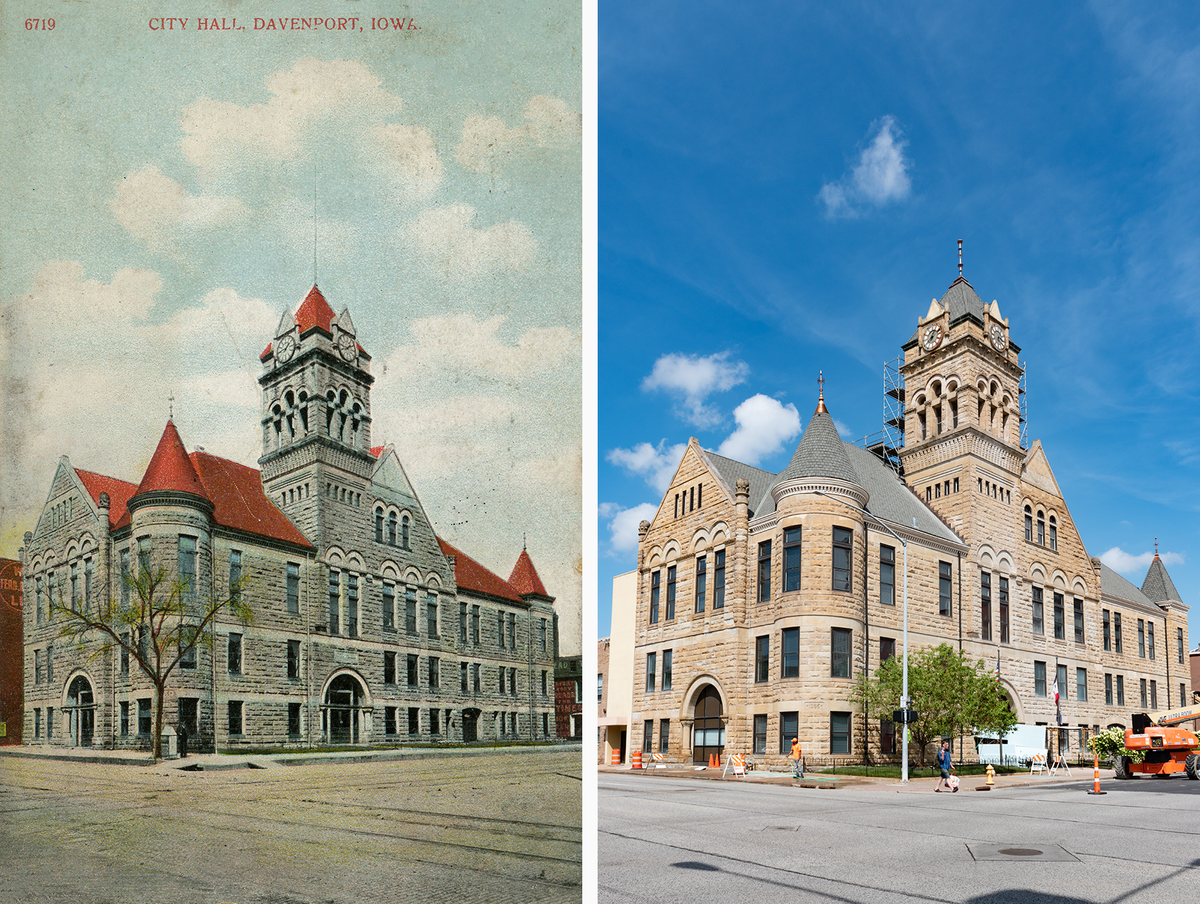

Designed by Iowa architect John W. Ross and completed in 1896, Davenport's Richardsonian Romanesque-style City Hall is one of a handful in the US to host a Socialist administration, after they swept to power in the 1920 municipal elections. Unlike their contemporaries in Milwaukee, the “sewer socialists” who governed the city for decades on the back of their effective public works programs, Davenport’s socialists failed to assemble a durable coalition, descended into infighting, and got killed in the next election. Politically, Davenport City Hall’s next century was more, uh, traditional. Renovated in 1980-1981, the building's red slate roof was replaced with the current grayish-blue shingles - yup, in this case the exuberant colors of the postcard were not the result of a colorist taking liberties, city hall just became more boring.

Like many bustling Midwestern towns in the 1890s, Davenport had outgrown its city hall. Under Mayor Henry Vollmer, in 1893 they kicked off a small competition to design its replacement. In addition to John W. Ross, C.K Howell (Chicago), H.D. Deane (Chicago), a Gustav/Carl Grandt Korn (Rock Island) submitted entries. Ross was kind of the typical hometown hero architect of the period, designing civic stuff, schools, homes, etc. around Davenport - I doubt he was ever going to lose. Out of the losing entries, Howell, who worked for Burnham & Root, crafted an interesting career designing homes in Richmond, Virginia as well as working as the house architect for Keith Circuit theaters across the south.

Construction on Ross’ design began in 1895, and the end result was this classic example of civic Richardsonian Romanesque. Thick masonry walls, sweeping arches, rusticated stonework - a built version of the word “weight”, an embodiment of municipal might. As a solid representation of the style, Davenport City Hall was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982 (and also because this is just the kind of old-timey institutional thing that gets listed).

A little more unique than its architectural style and preservation status is its role as a footnote in socialist history - Davenport is one of the largest US cities to have elected a socialist government, up there with Milwaukee (WI), Bridgeport (CT), Berkeley (CA), and Flint (MI). The Socialist Party of America’s success here after World War I was mostly the result of a cross-pressured German community who had existential issues with the two major parties - a socialism of circumstance rather than a robust mass coalition. More Bernie 2016 than Bernie 2020.

Davenport was one of the most German cities in the US in the 1910s, supporting two German-language newspapers in Der Demokrat and Die Iowa Reform. The Republican Party was mostly out of the question for Davenport’s Germans - the GOP supported Iowa’s thriving temperance movement and aggressively pursued prohibition of alcohol. Then, the Democratic Party joined the anti-German hysteria after the U.S. entry into World War I. A phenomenon across the US, things were particularly bad in Iowa - in 1918 the state’s Republican governor William L. Harding issued the Babel Proclamation, which prohibited the public use of all languages other than English (xenophobic, flagrantly unconstitutional, and just deeply shitty, it was repealed after six months).

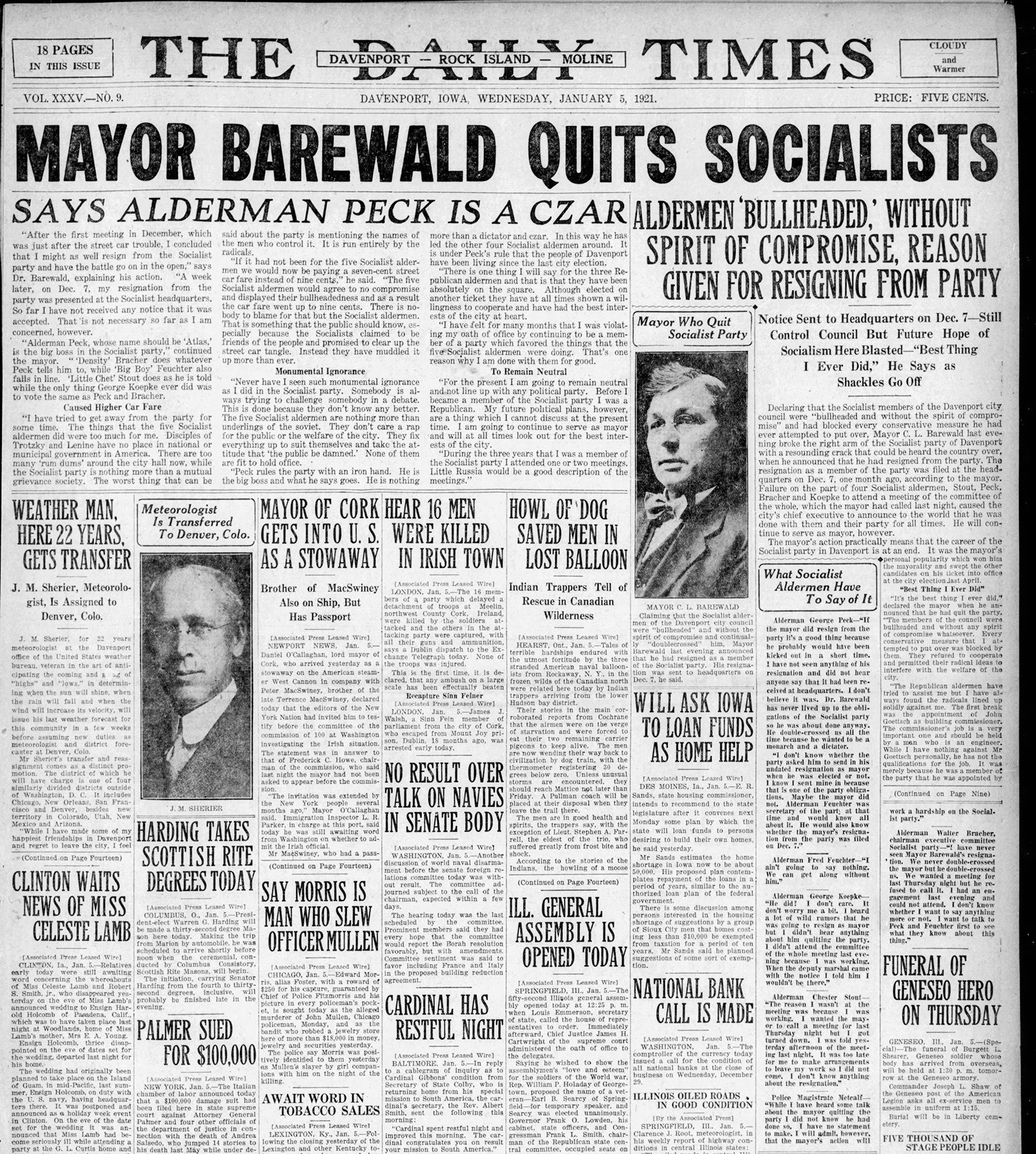

Royally pissed off and politically homeless, Davenport’s Germans voted en masse for the Socialist Party, who had made real political progress nationally with Victor Berger in Congress and Eugene V. Debs winning nearly a million votes for president from a prison cell in 1920. Running on free textbooks in schools, increased teacher pay, and removing military training from the education system, Davenport’s socialists romped to victory in 1920. They won the mayoralty, elected five of eight seats on the city council, and took every office except for City Treasurer. Their surnames help tell the story of their support: Mayor Barewald, Alderman Feuchter, Alderman Bracher, Alderman Koepke, etc.

Led by Mayor Barewald and by George Peck in the city council, they initiated a large public works program that included building sewers (of course), a public pool, and street paving…but things went off the rails pretty quickly. Barewald, a German-American and former Republican, was a pretty clear example of socialism of circumstance - he resigned from the party within nine months. Unhappy with infighting and a refusal to compromise with the Republicans on the city council, in his resignation letter he said, “every Socialist local is a mutual grievance society”. The regional press and the elite organizations of Davenport ate that shit up - after leaving the party, Barewald entered a rotary club luncheon to a standing ovation.

City government was kind of shitshow after that. There was a bugging scandal (it appears that the Socialist aldermen had bugged the mayor’s office), two of the elected city officers were charged with misuse of public funds, and infighting paralyzed the city council. Handed a political opening by a bizarre confluence of events - prohibition, xenophobia, and world war don’t often come along all at once - Davenport’s socialists fumbled it badly. In 1922, hoping to capitalize on women voters after the ratifcation of the 19th Amendment, the Socialists chose Lucy Claussen as their mayoral candidate, the first woman to run for mayor of Davenport. Didn't help much. All of Davenport's socialists but one - weirdly, the Socialist Police Magistrate - lost in 1922. As Councilman Fred Feuchter put it, “we had the power and we lost it.”

Production Files

Further Reading:

- A fascinating journal article on the Davenport Socialists of 1920 by William H. Cumberland.

Member discussion: