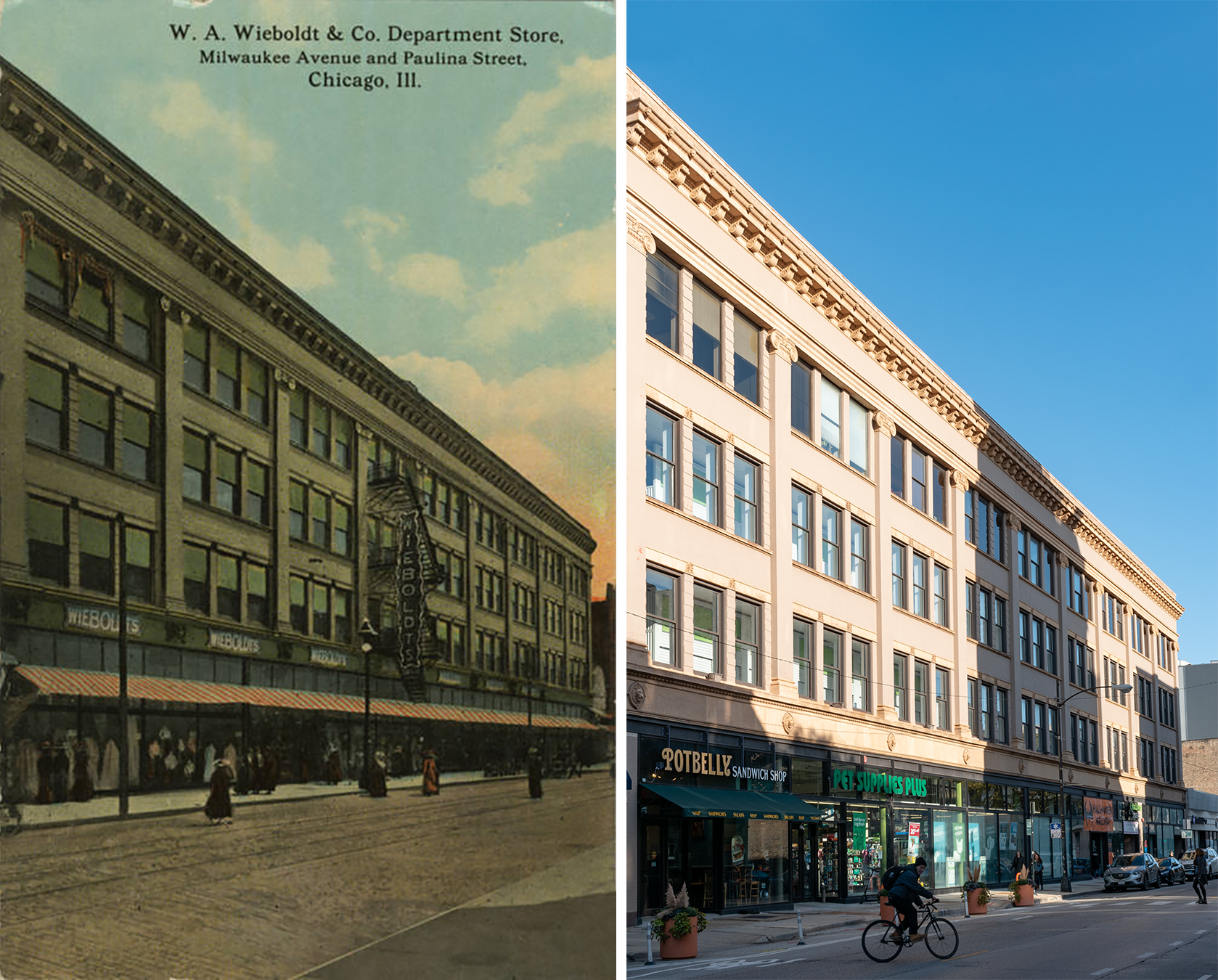

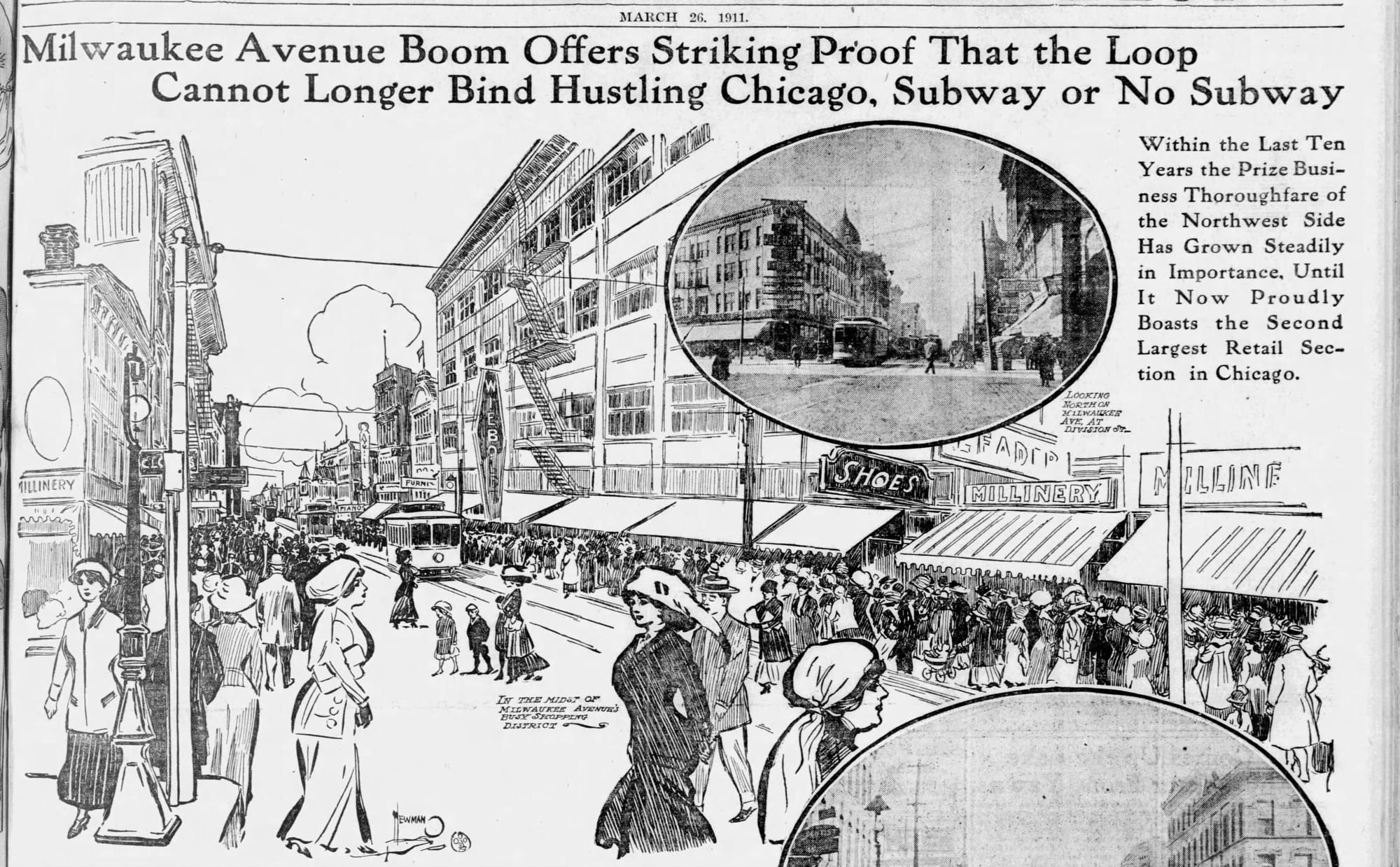

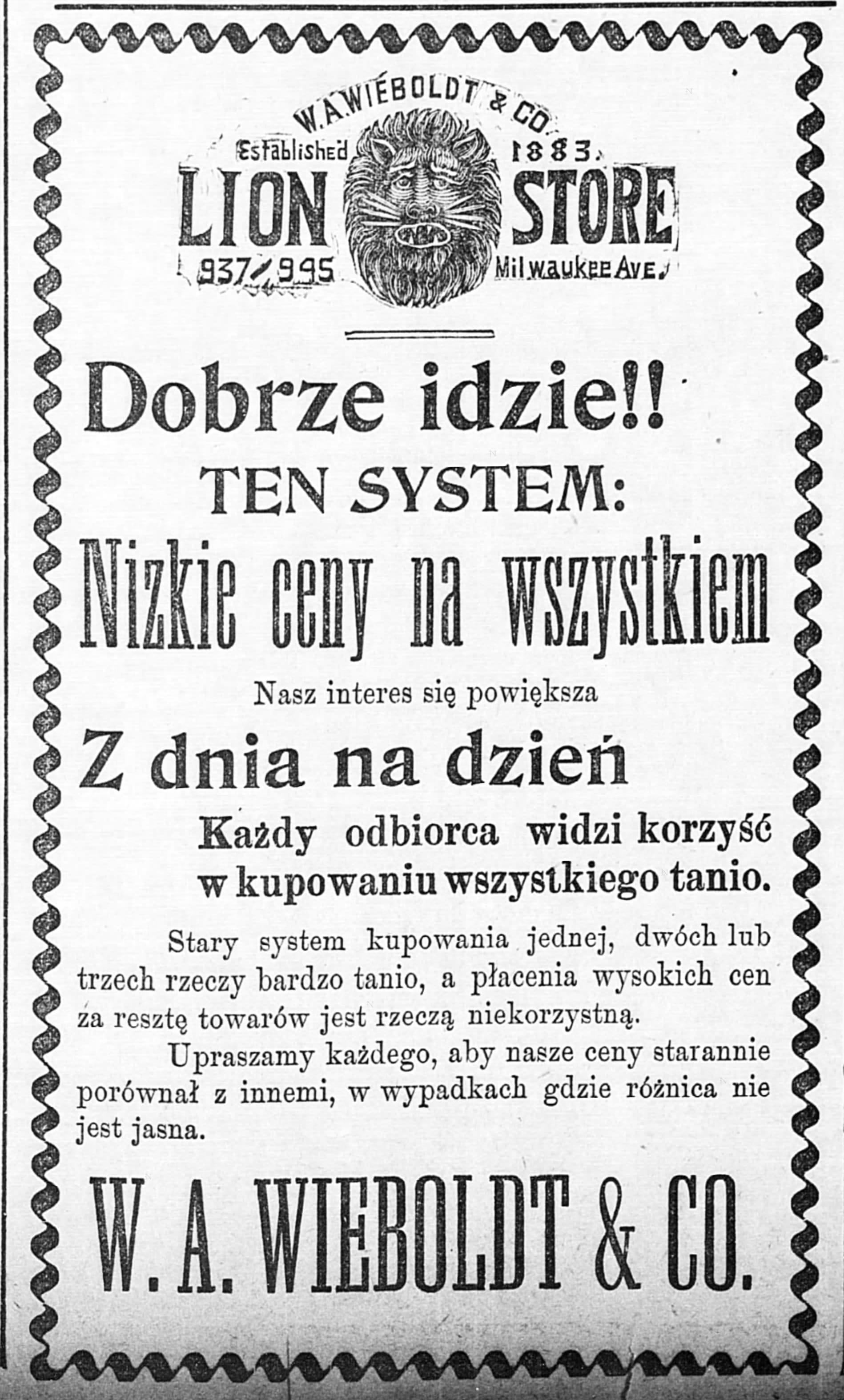

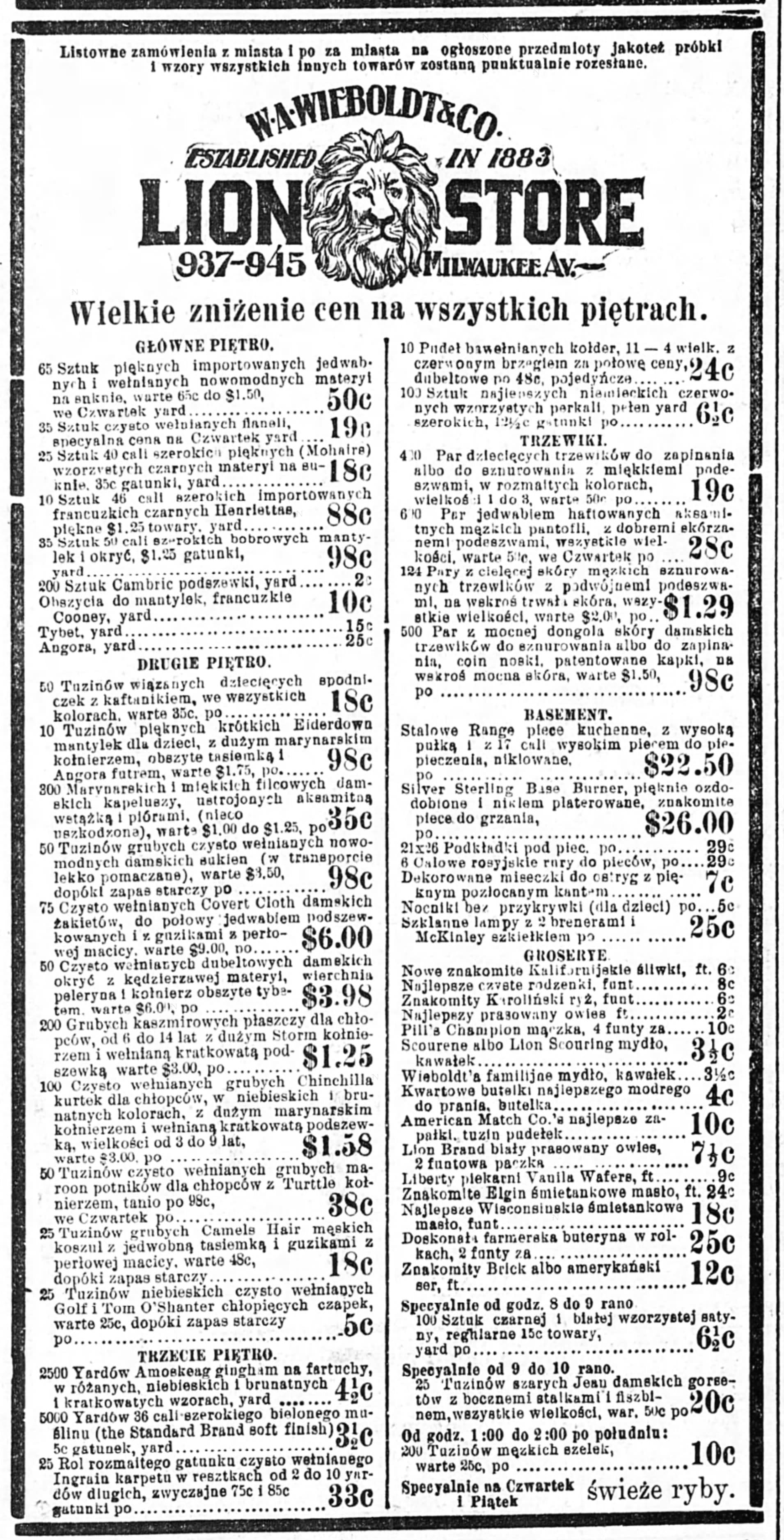

From burning rubble and the buying power of the German and Polish working classes, William A. Wieboldt built a department store empire out of this location on Chicago’s Milwaukee Avenue. Known as the Lion Store, Wieboldt’s first shop at this site burned down in November 1897. By Christmas he’d bought the land, less than six months later Wieboldt's new Lion Store (designed by architect R.C. Berlin) opened, and within five years the department store had doubled in size. Rather than compete with the big boys downtown, W.A. Wieboldt focused on serving customers in their own language and in their own neighborhoods, and over a century that approach grew the company into a 15 store chain.

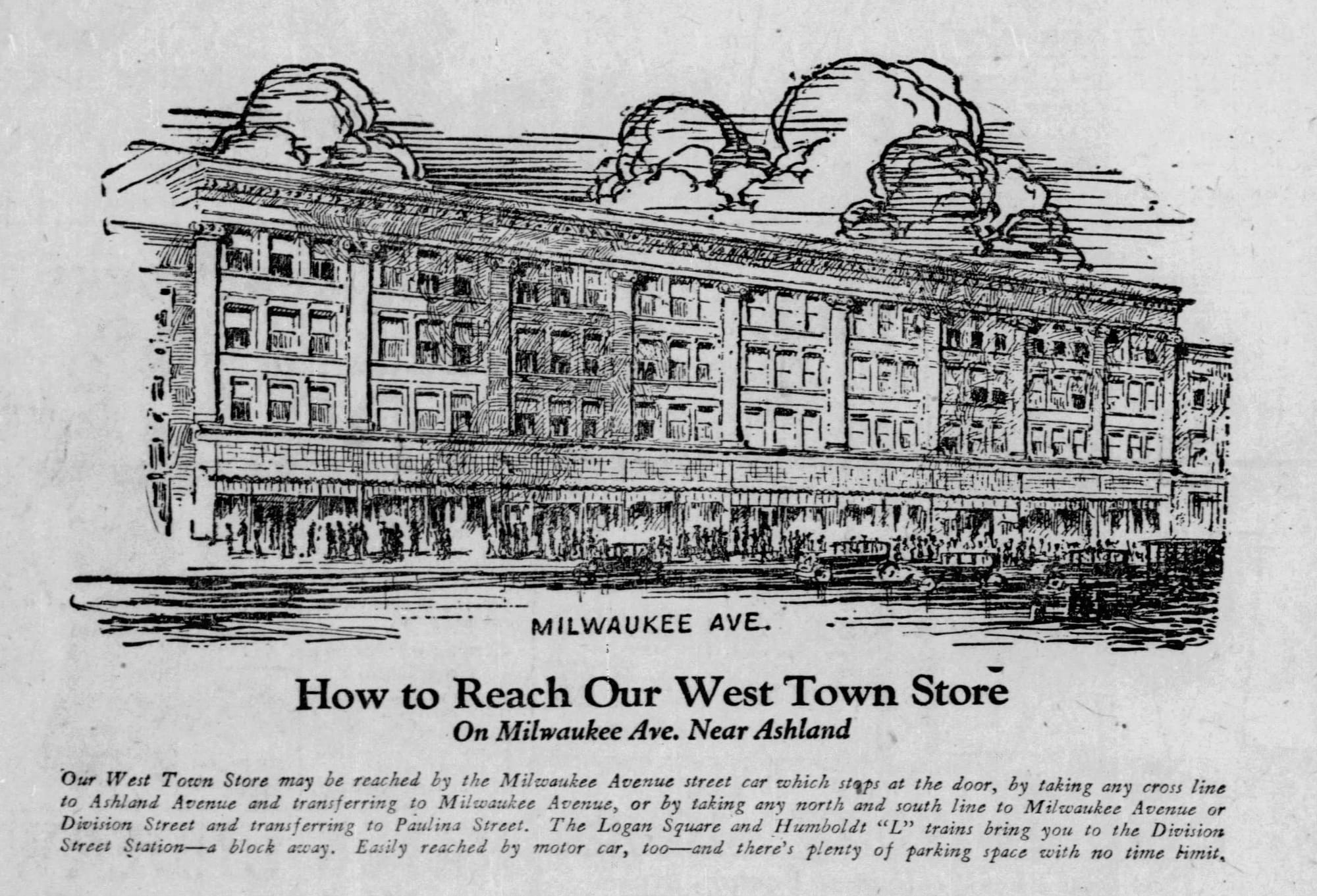

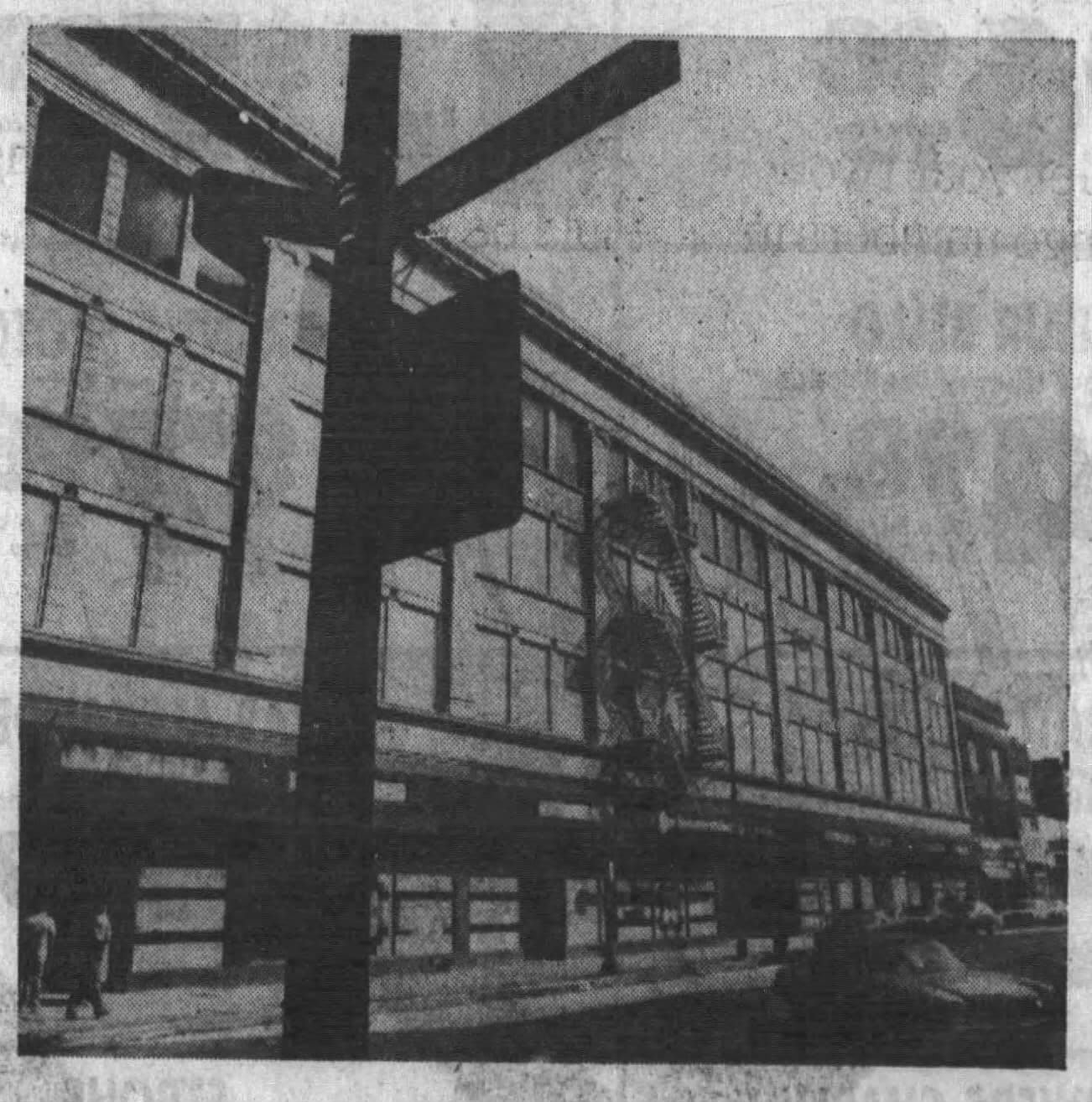

With the company stumbling into the 70s, Wieboldt’s shuttered this location in 1975. The vacant building became wrapped up in a braindead urban renewal project—West Town Center—that demolished most of its surroundings for a parking lot and forced hundreds people from their homes, all subsidized with millions of dollars of federal money and Cook County tax breaks. Despite shoveling public money and parking spaces at a “problem” that likely would’ve solved itself within a decade or two, today the old Wieboldt’s store is home to some random retail and self-storage space—not exactly an inspiring use of the building.

So, what’s changed?

- A 1911 addition added two window bays worth of width to the southeast end of the building (there are seven banks of windows in the postcard, nine in the photo).

- RIP Milwaukee Avenue streetcar.

- Removal of the hanging sign and the fire escape.

- The building was once red (...but tbh I'm not 100% sure it was actually red when this postcard was published).

Less than a decade after arriving in Chicago from Germany, William A. Wieboldt opened his first shop in 1883 on Grand Avenue (in a building that—remarkably—is still there). Two years later, Wieboldt moved his store to the intersection of Milwaukee and Paulina—but initially across the street, on the northwest corner.

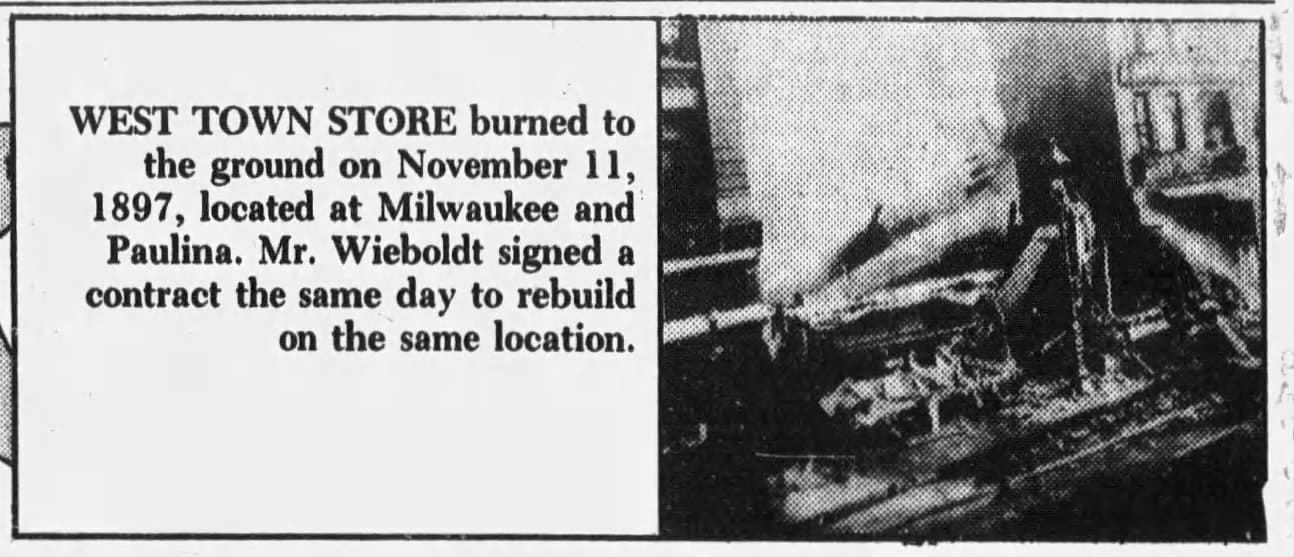

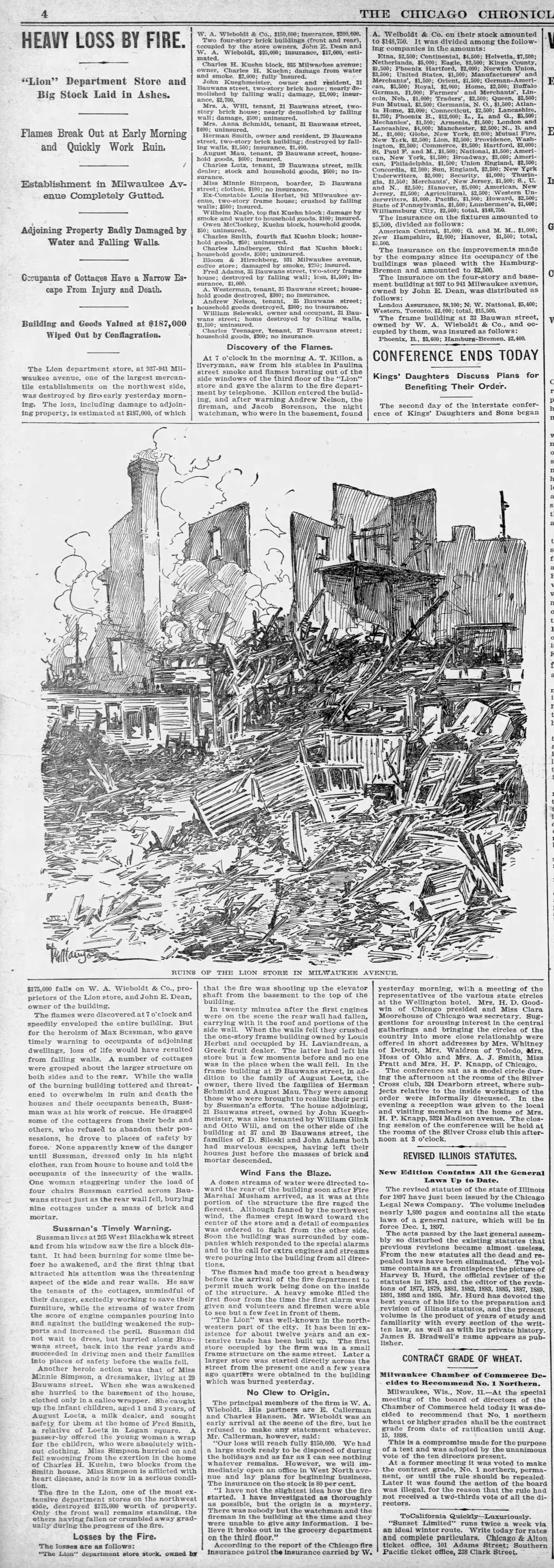

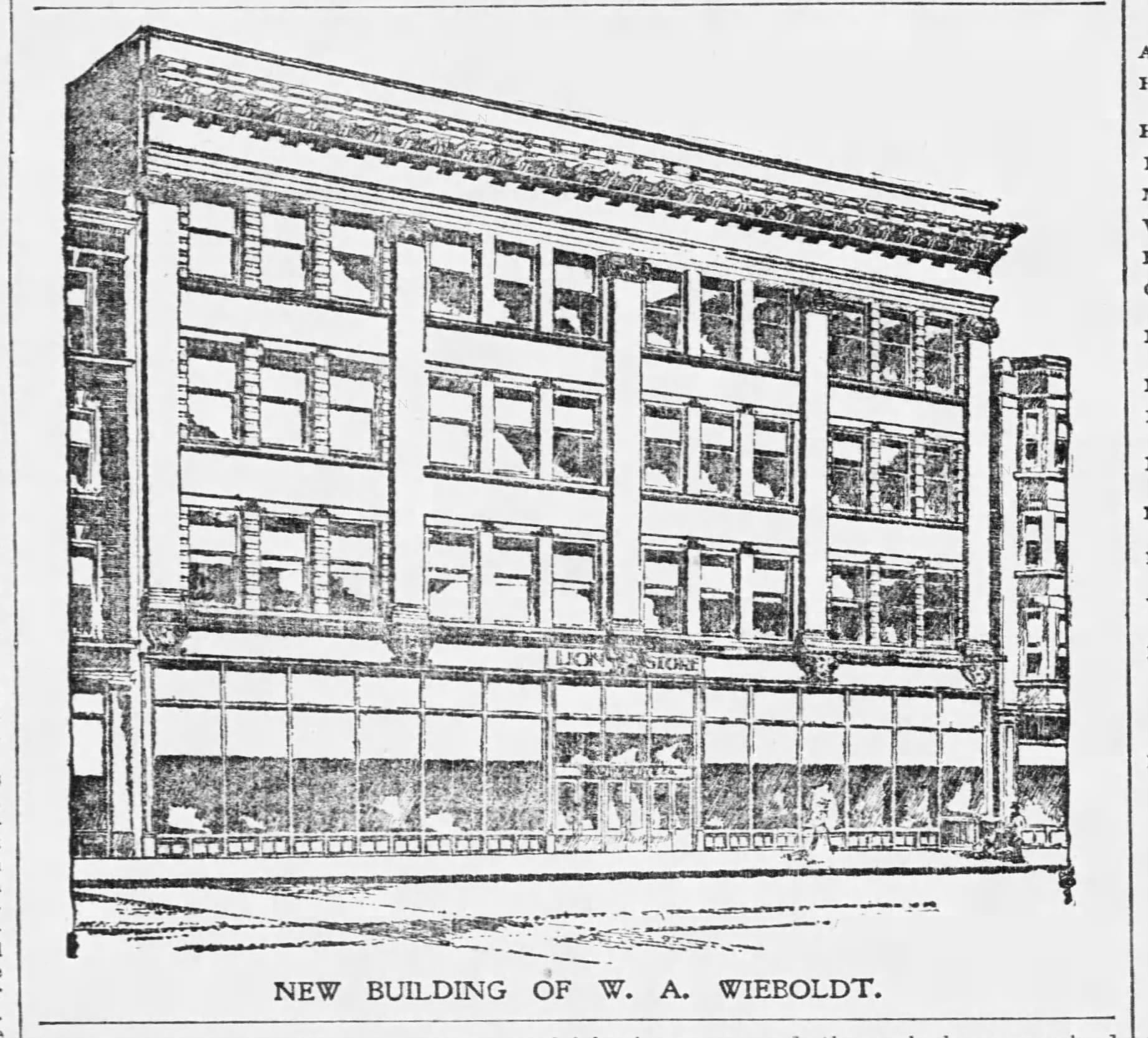

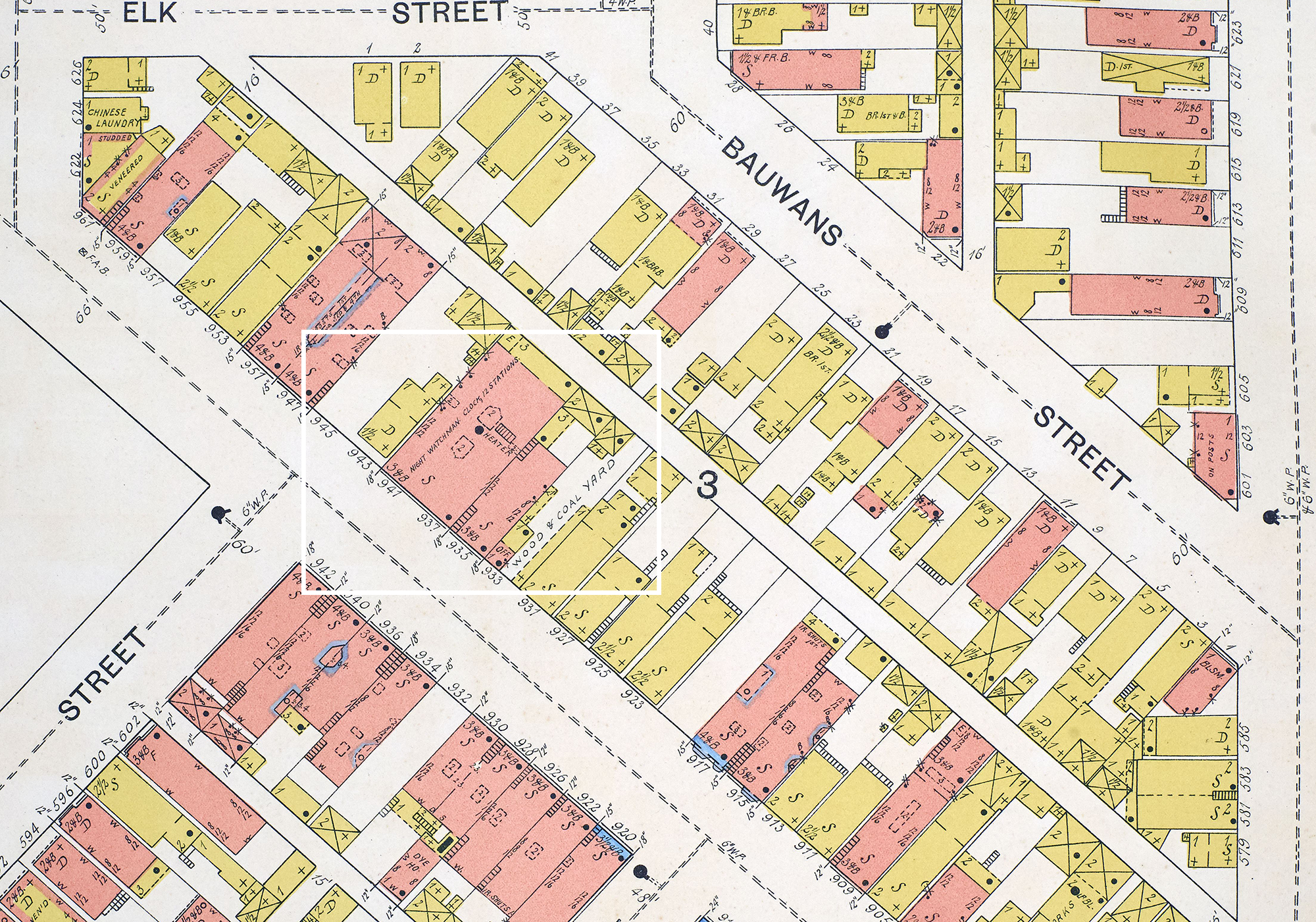

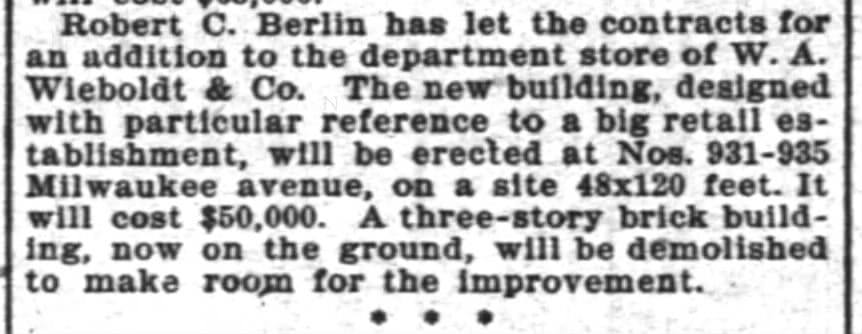

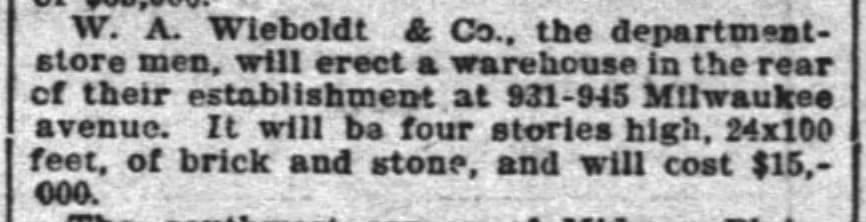

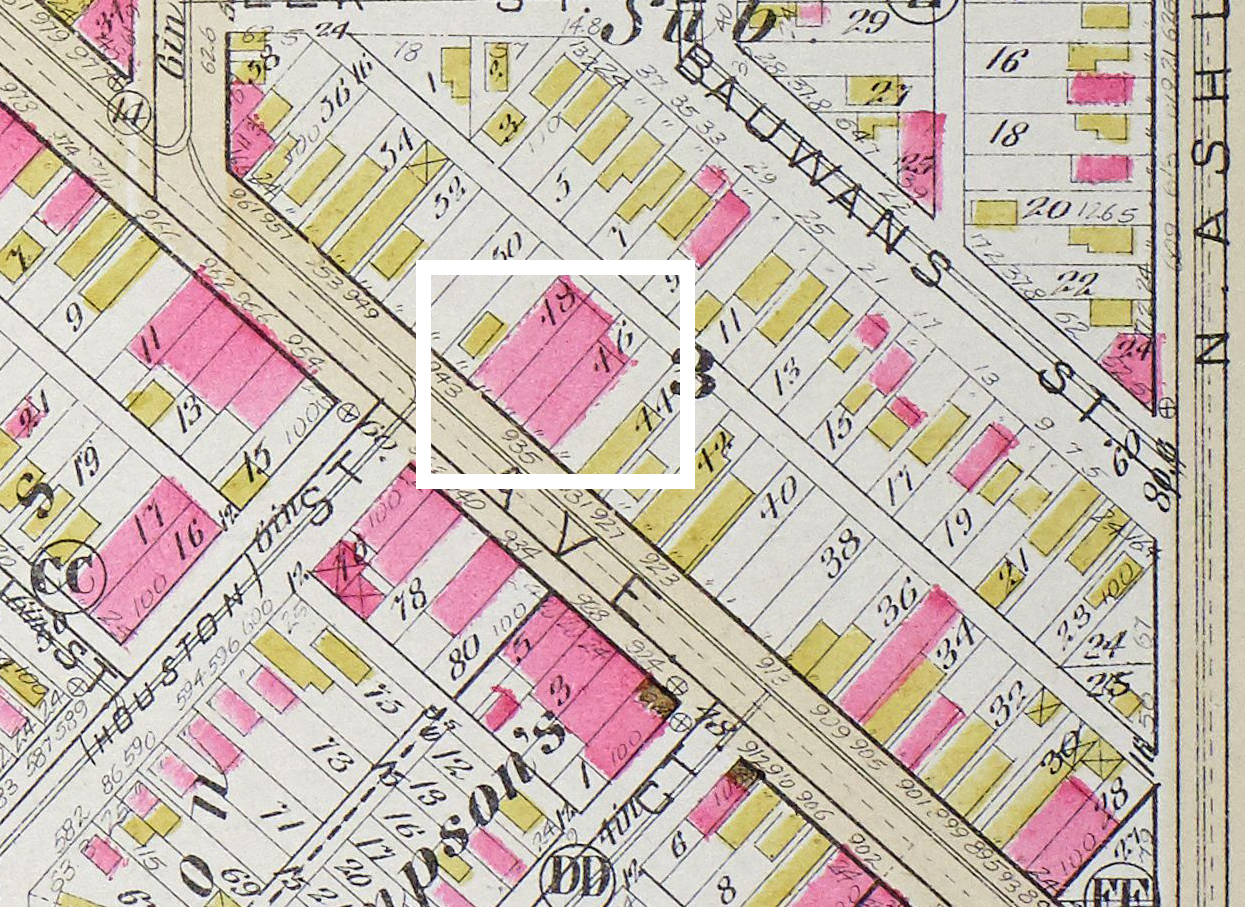

After renting space in a building on this site in 1887, Wieboldt’s Lion Store grew into a bustling neighborhood destination, but disaster soon struck. The Lion Store burned on November 11th, 1897, with flying embers and collapsing walls destroying many of the surrounding worker cottages and wood frame homes on Bauwans Street. Wieboldt’s losses from the fire exceeded their insured value, but the store must have been raking it in—W.A. Wieboldt turned around and bought the land under the burned store, hired architect Robert C. Berlin to design him a new one, and opened the rebuilt Lion Store within six months.

First store location, 1832 W. Grand, 1960 Shareholders Report, the Internet Archive | 1832 W. Grand, 2019 Google Streetview | Photo of the burned Lion Store, 1897 (in the Chicago Tribune in 1986) | 1897 articles about the fire in the Chicago Chronicle, the Inter Ocean, and Dziennik Chicagoski | 1898 articles about the new building | 1953 Henry Crown Wieboldt fire story

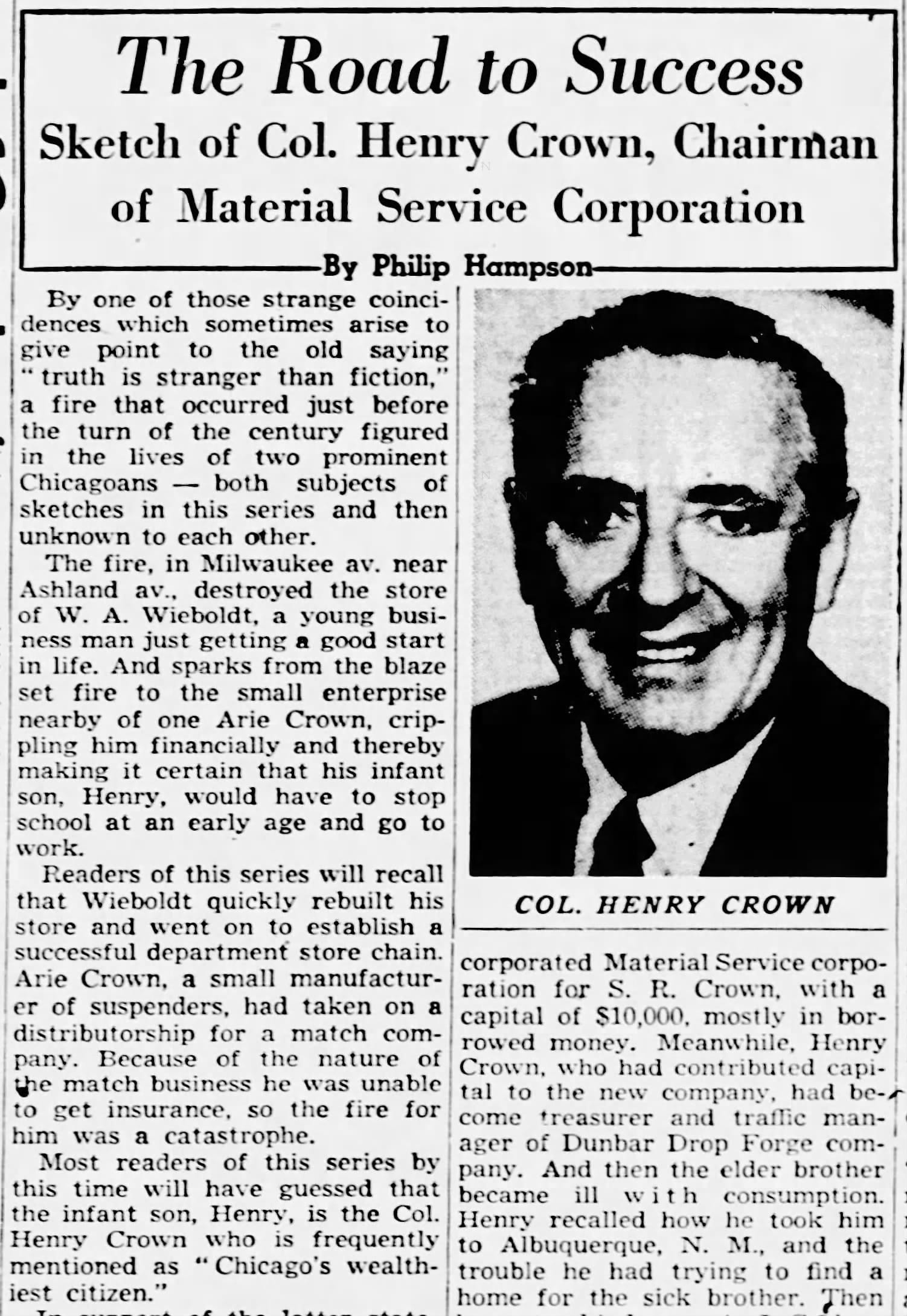

(the fire that destroyed the Lion Store also played a role in the mythology of another, even wealthier Chicago family—the Crowns, building material tycoons turned billionaire defense contractors. According to the family story, the 1897 fire destroyed match dealer Arie Crown’s entire [uninsured] stock, knocking the family back down the economic ladder and forcing young Henry—who’d go on to build the family fortune—out of school and into the workforce at a young age. [the newspapers don’t mention any Crowns or Krinskys in their list of losses, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it didn’t happen—they could’ve been so small potatoes it wasn’t worth mentioning.])

Chicago was the fastest growing city in North America at the turn of the century, powered by immigrants building homes and lives in neighborhoods like Wicker Park, and Wieboldt’s parlayed their patronage into two major additions in the rebuilt store’s first five years. The first, an identical four-story addition to the southeast, doubled the department store’s size. The second, a hulking warehouse at the back, kept the whole thing stocked. A third one, in 1911, added the southeasternmost section of the building—superficially identical, that section is actually reinforced concrete construction rather than masonry.

1892 fire insurance map | 1901 and 1902 articles about the additions | 1911 streetscape sketch | 1914 Sanborn Fire Insurance map | 1920s | 1926 ad | Lions on the facade, 2025

Robert C. Berlin—William A. Wieboldt’s personal and professional architect of choice—designed the original department store as well as the additions. Berlin’s firm was one of those productively lucky right place, right time firms that helped build Chicago into a metropolis in the 1890s and 1900s. Berlin was born in Illinois, but trained in Germany and Switzerland—as two North Side Germans, it’s easy to imagine Berlin and Wieboldt running in the same social circles. Besides this department store, Wieboldt also tapped his compatriot to design his home in Lakeview (extant) and the Division Street Y.M.C.A., which Wieboldt helped finance with its largest donation. In this case, the end result was vaguely Chicago School and utilitarian, a textbook neighborhood commercial building. With its predecessor already known as the Lion Store, Berlin's firm decorated the facade with ornamental lions.

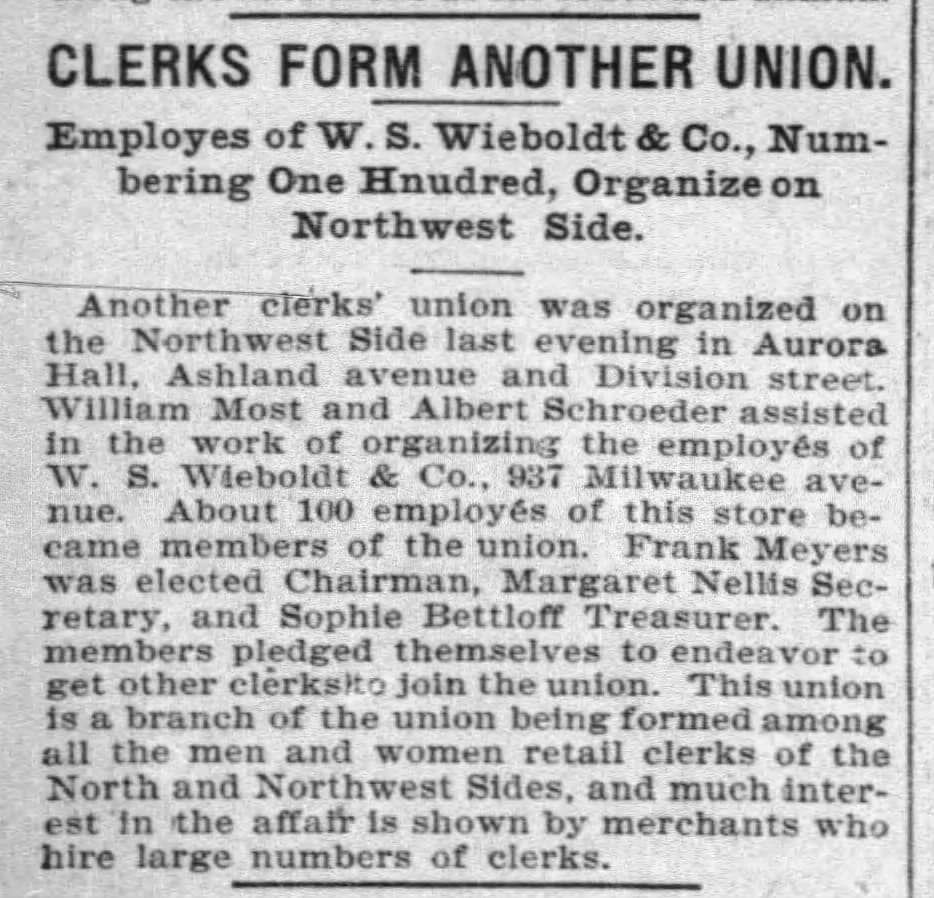

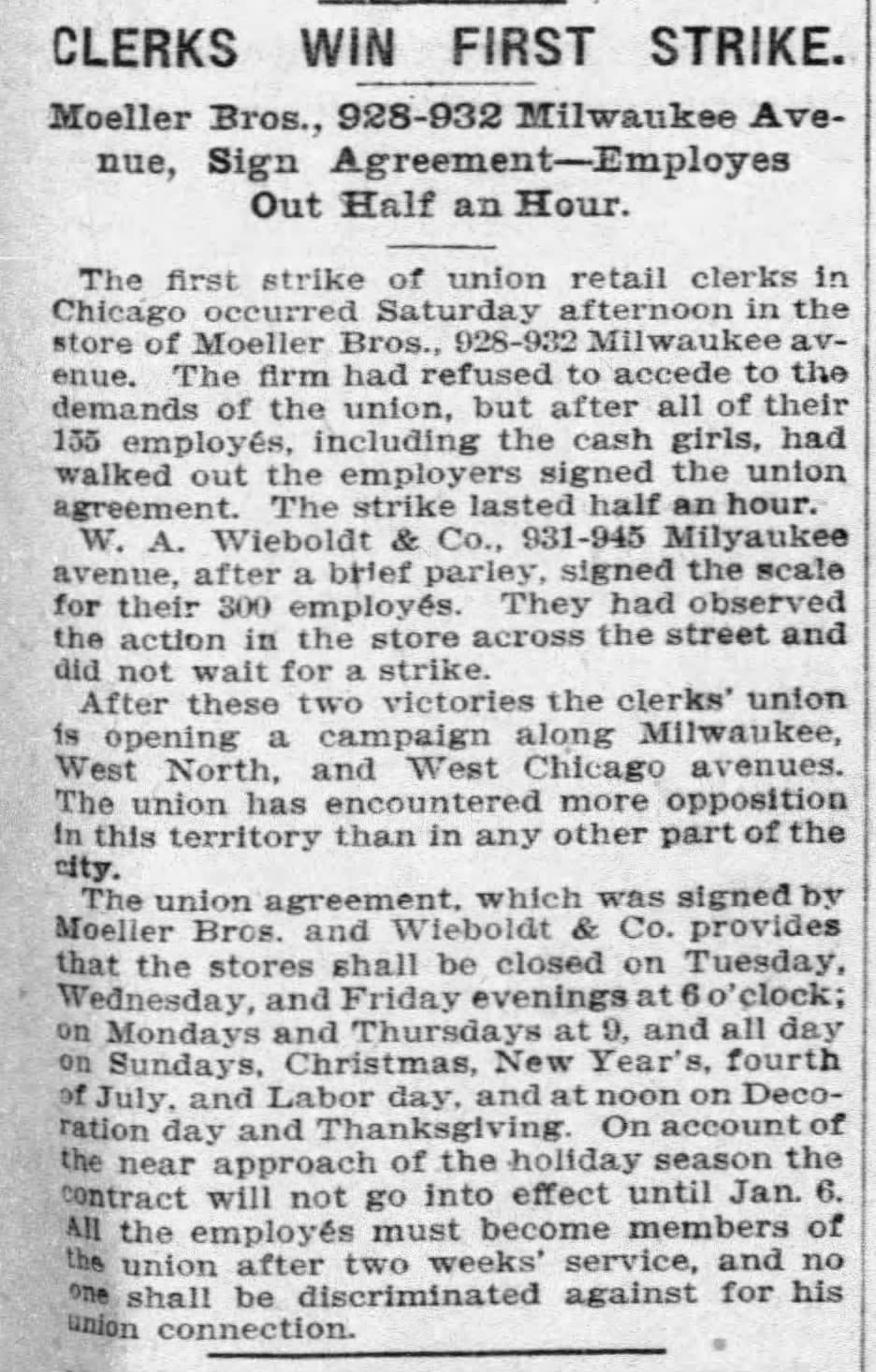

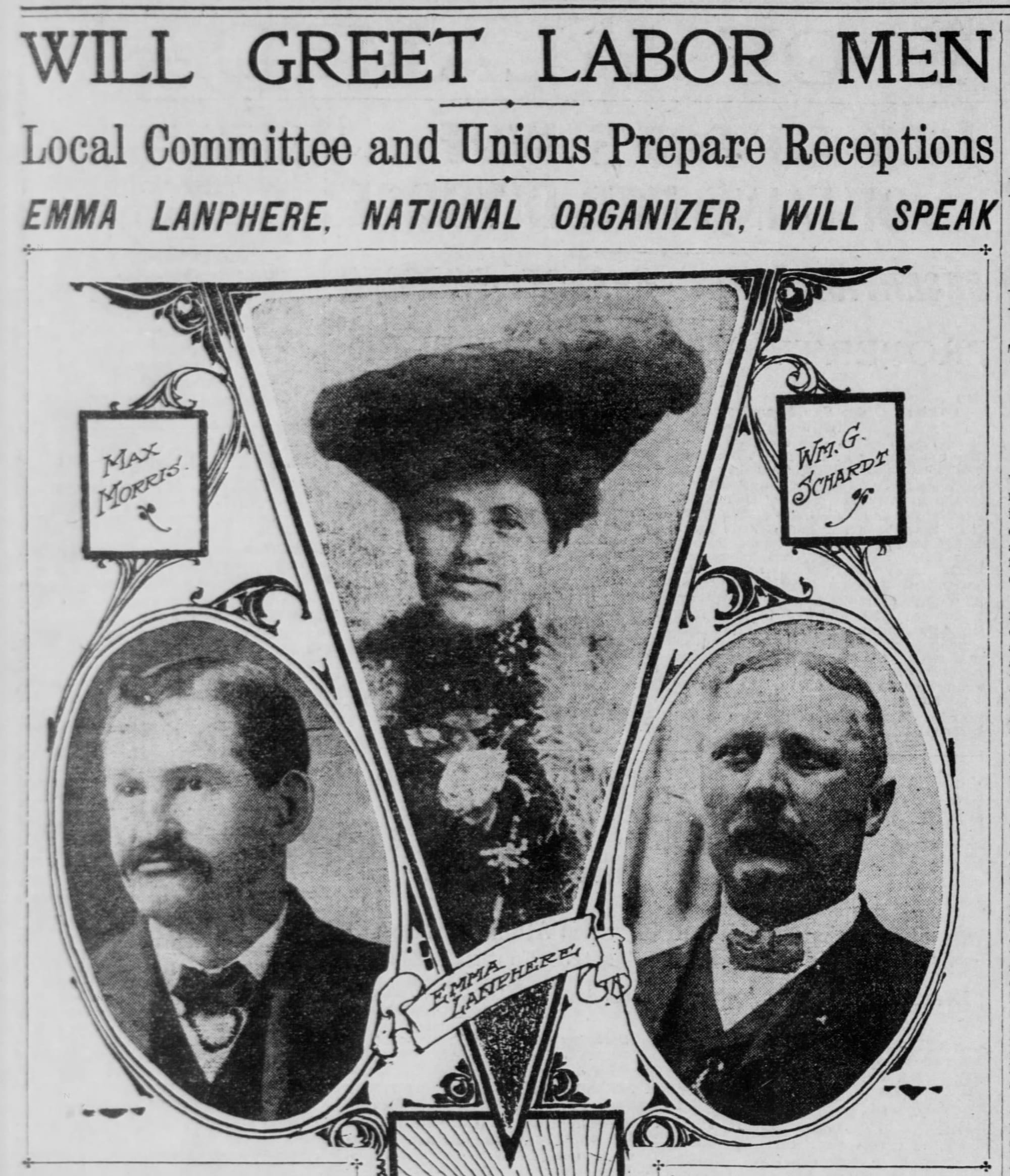

A growing retail empire with a powerful boss in a Chicago with a deep, bold, and highly organized labor movement—it will not surprise you to hear that there was conflict between workers and management here, in particular a months-long strike lead by Retail Clerks' National Protective Association organizer Emma Lanphere in 1904. Wieboldt’s had actually signed an initial contract with the union in 1902 without a strike after the union struck the Moeller Bros. department store across the street. With the RCNPA growing from 16,000 to 60,000 members between 1900 and 1904, for the next contract the union came back asking for better working conditions, fewer working hours, and a day of rest on Sundays. Wieboldt’s refused. The ensuing strike from Lanphere and the clerks union included boycotts, organizing at churches, and—most powerfully—sympathy strikes, with aligned teamsters refusing to deliver to the department store (labor movement solidarity sufficiently threatened the power of rich assholes that the federal government outlawed sympathy strikes in 1947 with the Taft-Hartley Act).

Union forms, 1901 | Wieboldt's signs a contract with the union, 1902 | 1904 articles about the retail clerks' strikes lead by Emma Lanphere

(I can’t figure out how the strike ended—it doesn’t look like it made the news—which makes me think everyone involved ended up unhappy. The RCNPA still exists, sorta—its successor, the Retail Clerks International Union, merged with Amalgamated Meat Cutters in 1979 to form the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union.)

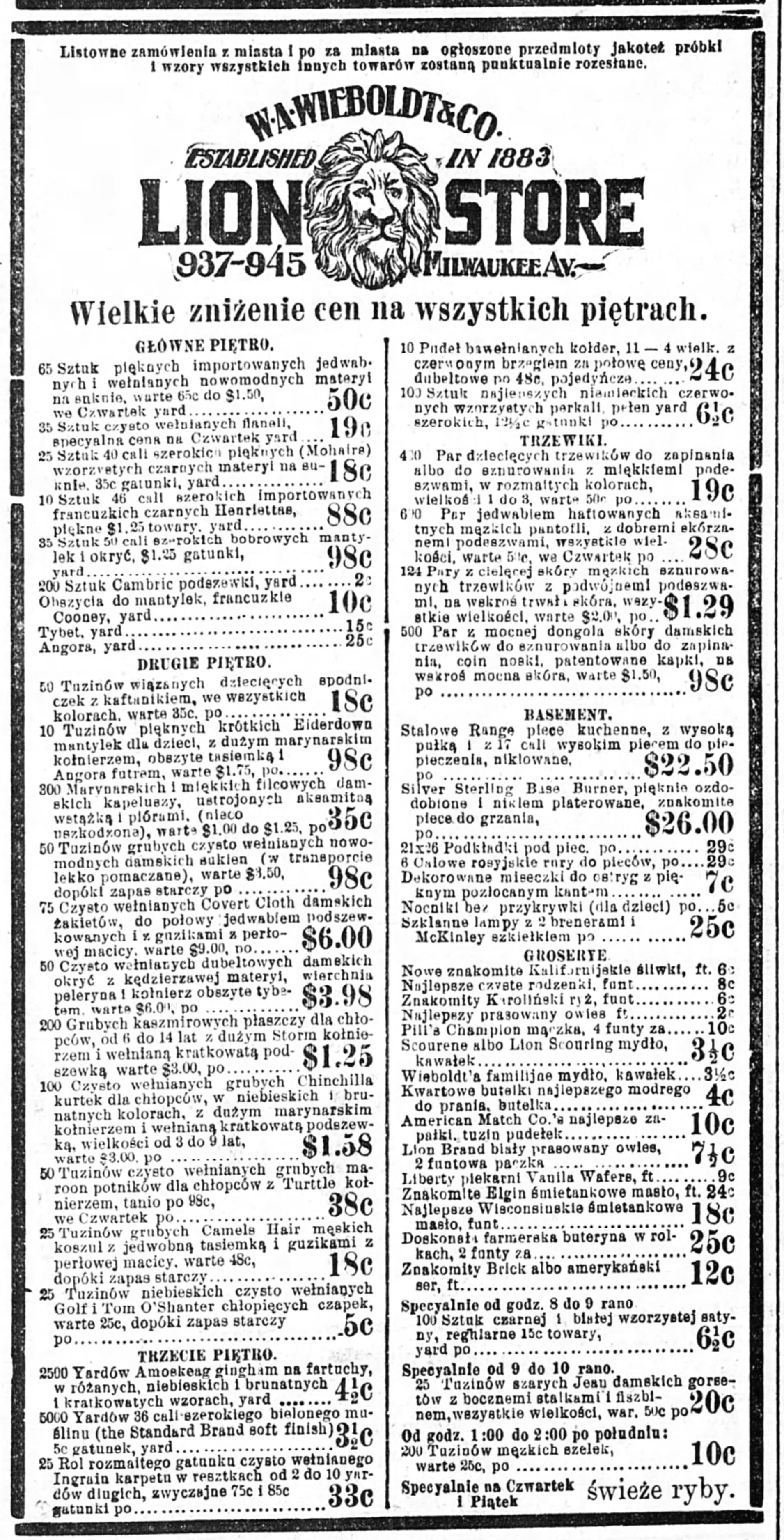

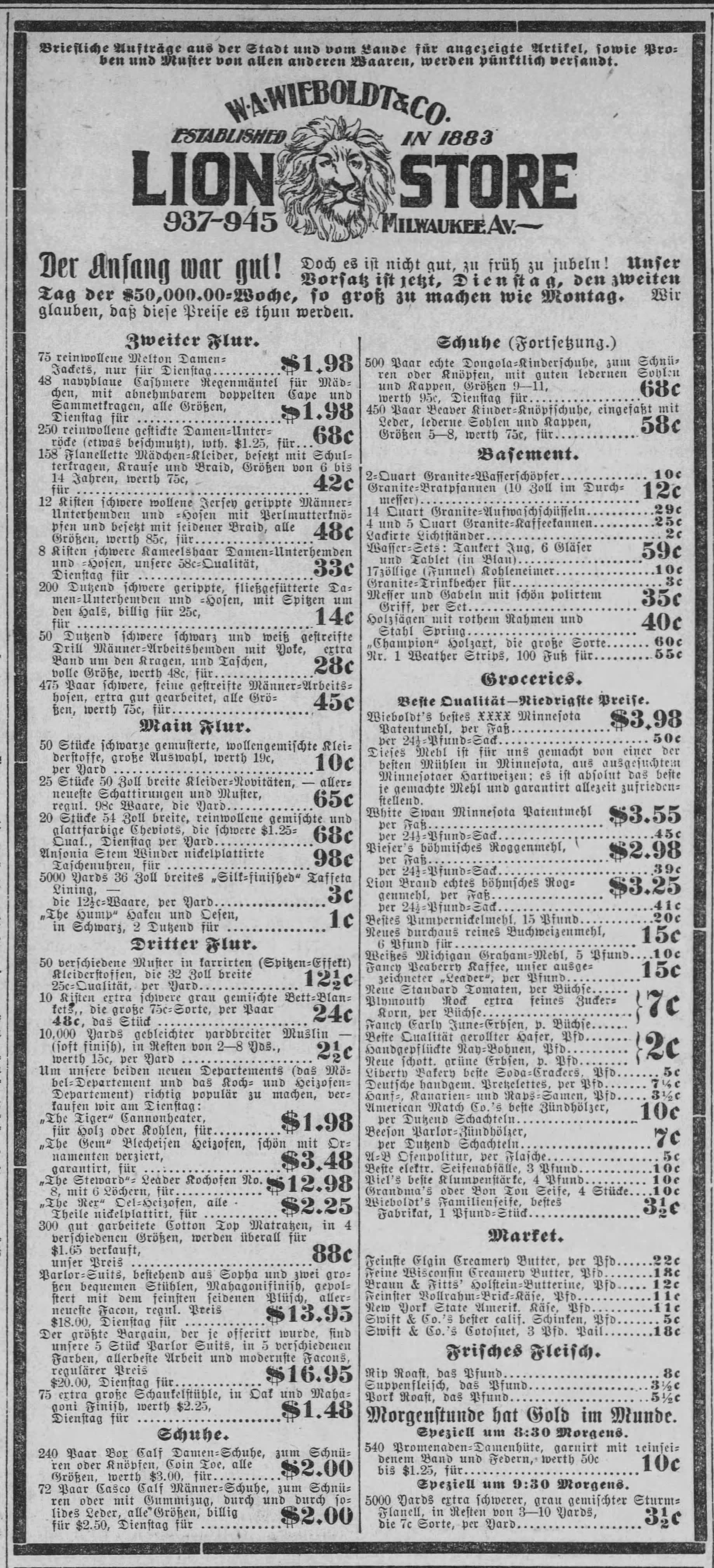

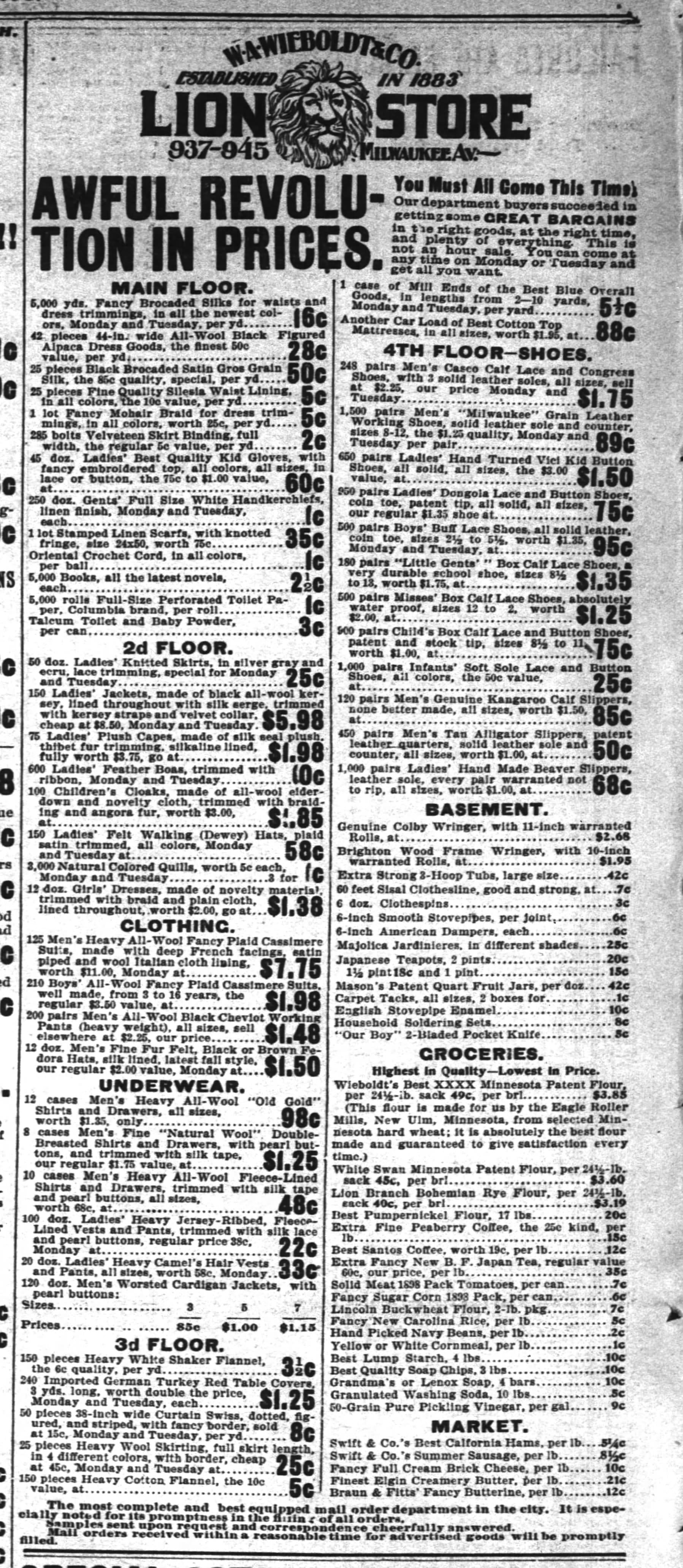

Selling clothing and furniture, with a bakery and a grocery store, Wieboldt’s employed more than 700 people in this department store at its peak. Wieboldt’s thrived as the neighborhood department store for the Northwest Side’s Polish and German communities, serving them in their own languages. By 1952, the multilingual, multi-ethnic department store of Chicago’s white working class had expanded into a six store chain.

1898 Lion Store ads in Polish, German, and English | 1899 Polish-language ad | 1898 German-language ad | 1904 and 1905 help wanted ads for German and Polish speakers

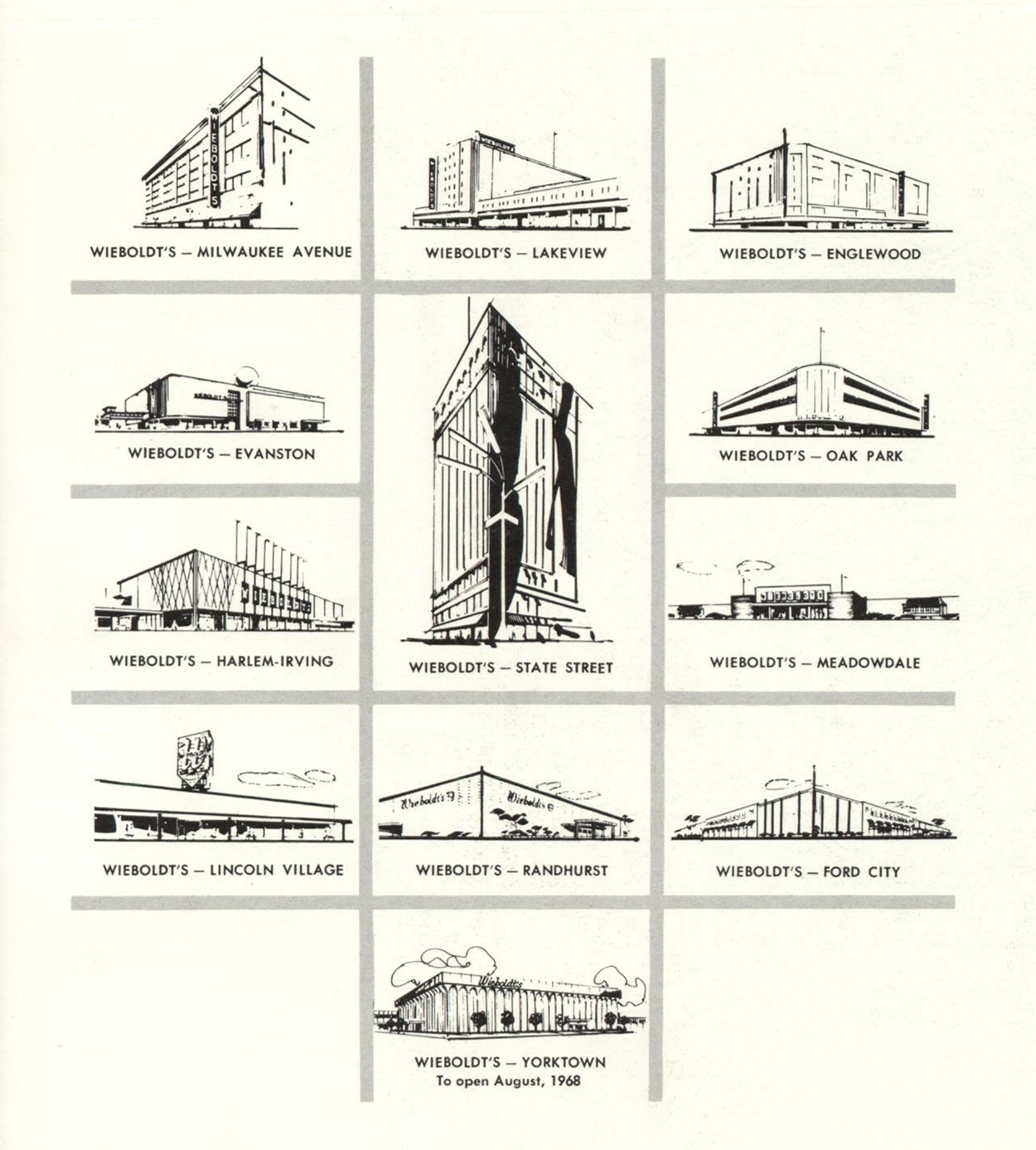

White flight, urban renewal, and changing shopping habits broke Wieboldt’s original business model by the 1960s, and the company tried to outrun those trends by expanding to the suburbs and—more shockingly—into the Loop (they acquired Mandel Bros. department store on State Street).

(...it didn’t work)

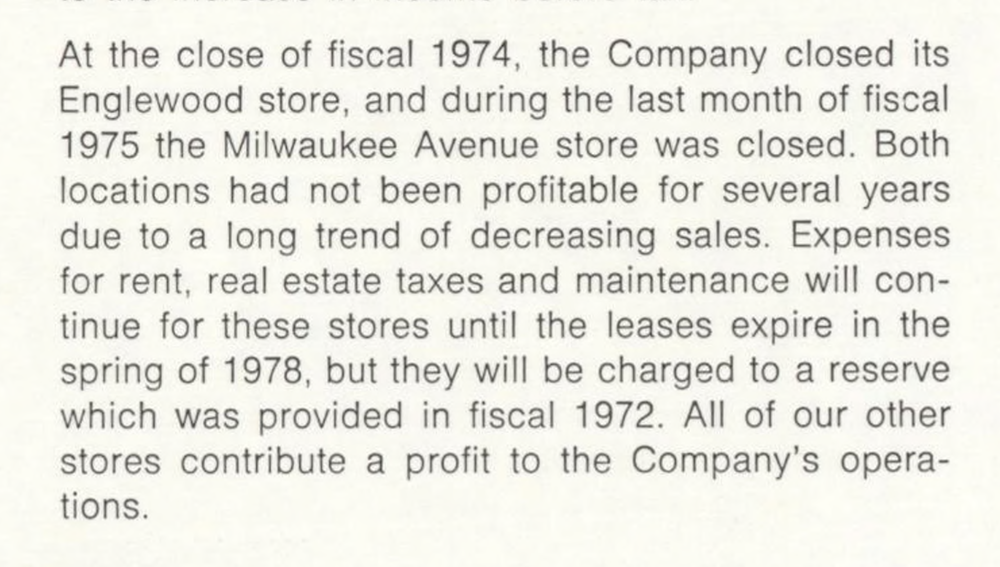

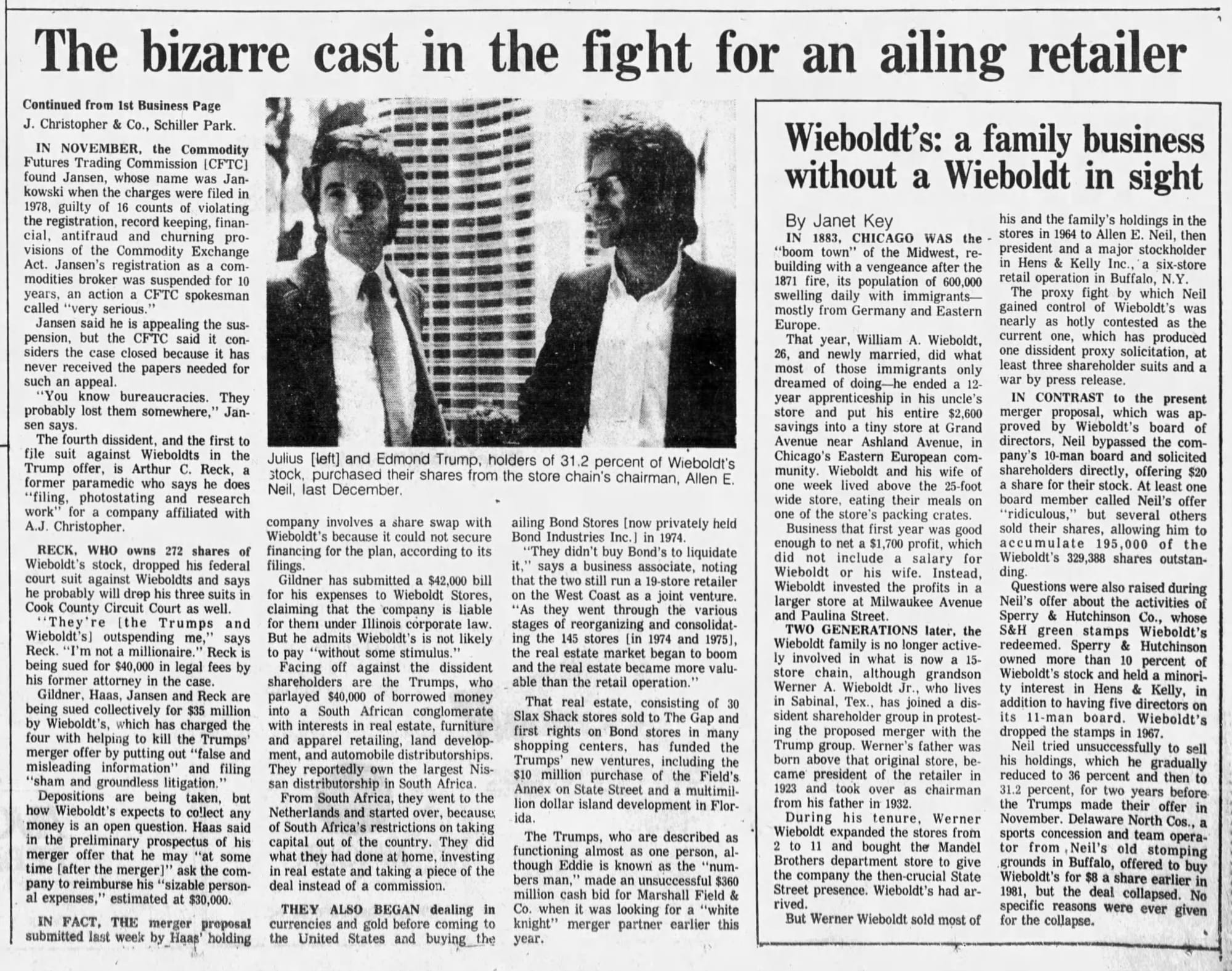

The Wieboldt family cashed out in 1964, selling to Allen Neil, the head of Buffalo-based department store chain Hens & Kelly. The mother store that birthed a local department store empire, Wieboldt’s closed this location in 1975 (a year earlier, the company had closed their Englewood store—the effect of urban renewal and disinvestment wasn’t subtle). While this store had closed, Wieboldt’s muddled on into the mid-1980s—the company had 15 locations as late as 1982.

A struggling department store in the 1980s, any guesses what killed it?

1953, James S. Parker Collection, University of Illinois at Chicago Library | Locations, 1967 Shareholders Report | 1975 Shareholders Report, Wieboldt's closes on Milwaukee | 1982 battle for control of Wieboldt's | 1985 articles about the buyout | 1987 articles about the bankruptcy and liquidation of Wieboldt's

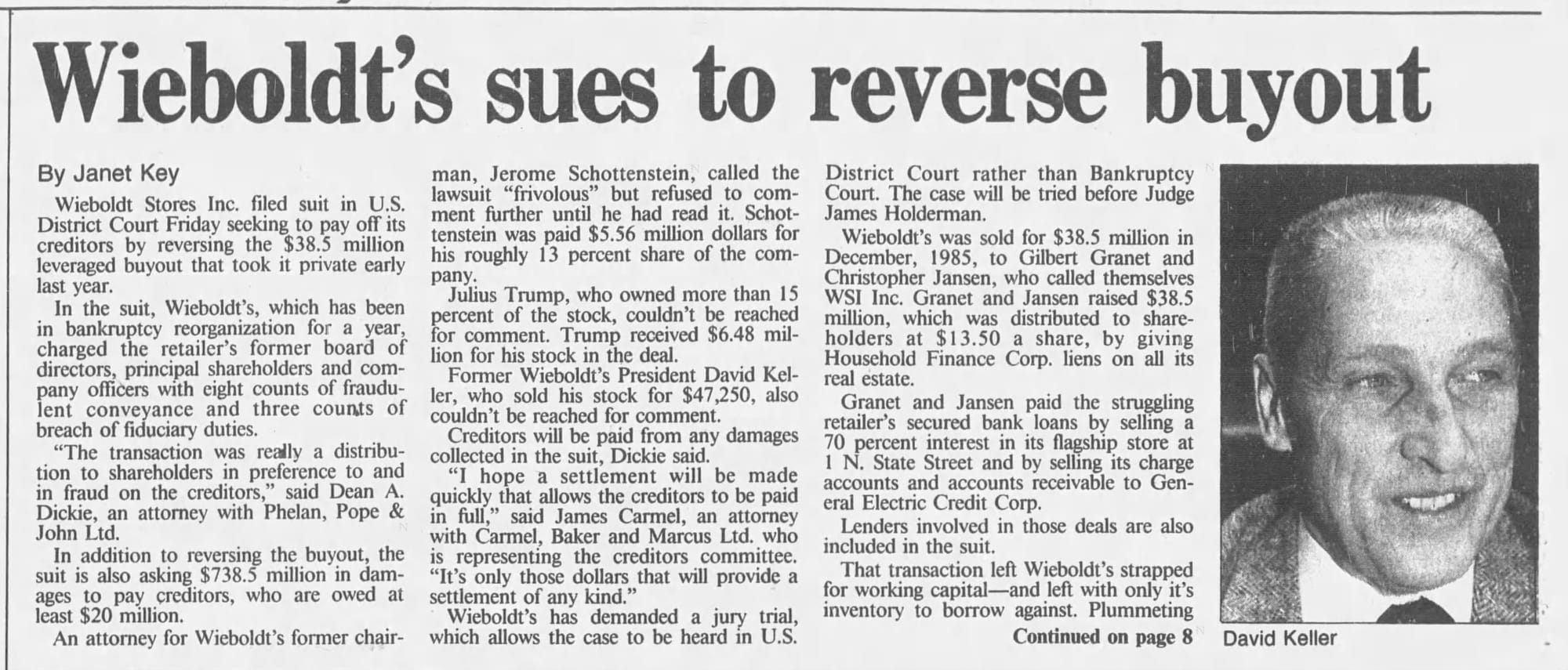

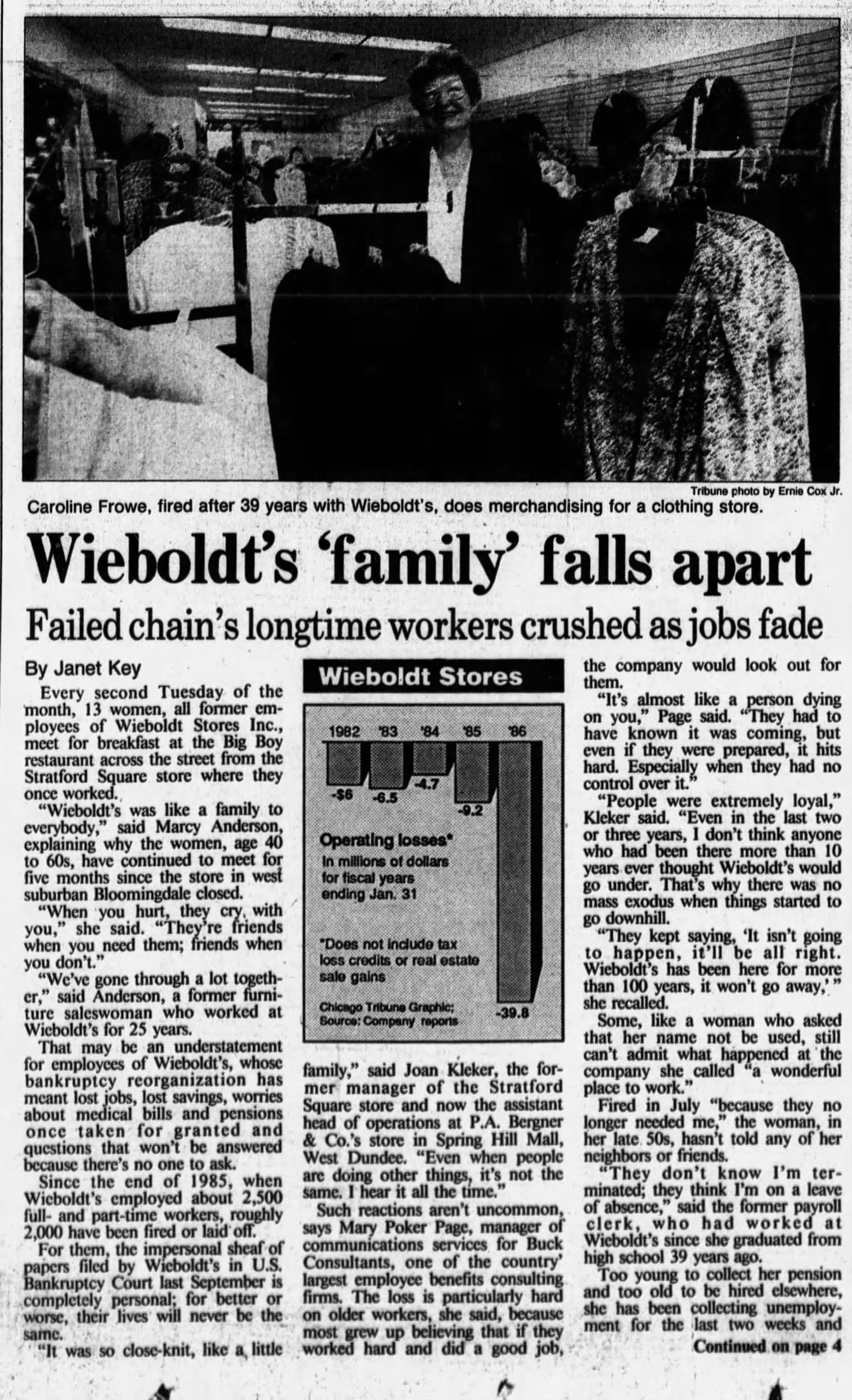

…a leveraged buyout, of course. In 1985 Baytree Investors—Gilbert Granet, Bernard M. Krakower, and Christopher A. Jansen—took out a shitload of debt to buy Wieboldt’s and then immediately dumped that debt back onto the company. Shockingly, throwing millions of dollars of debt onto the balance sheet of a declining department store chain wasn’t helpful, and by 1987 Wieboldt’s had declared bankruptcy and was in liquidation. A fraud lawsuit in connection with the LBO was settled just before going to trial in 1991 (but one of the Baytree Investors, Chris Jansen, would later end up in prison for tax fraud). It’s hard to look at the state of department stores today and say that Wieboldt’s would still be around if not for the leveraged buyout, but the LBO certainly hastened the collapse of a local institution that still employed thousands of people in 1987.

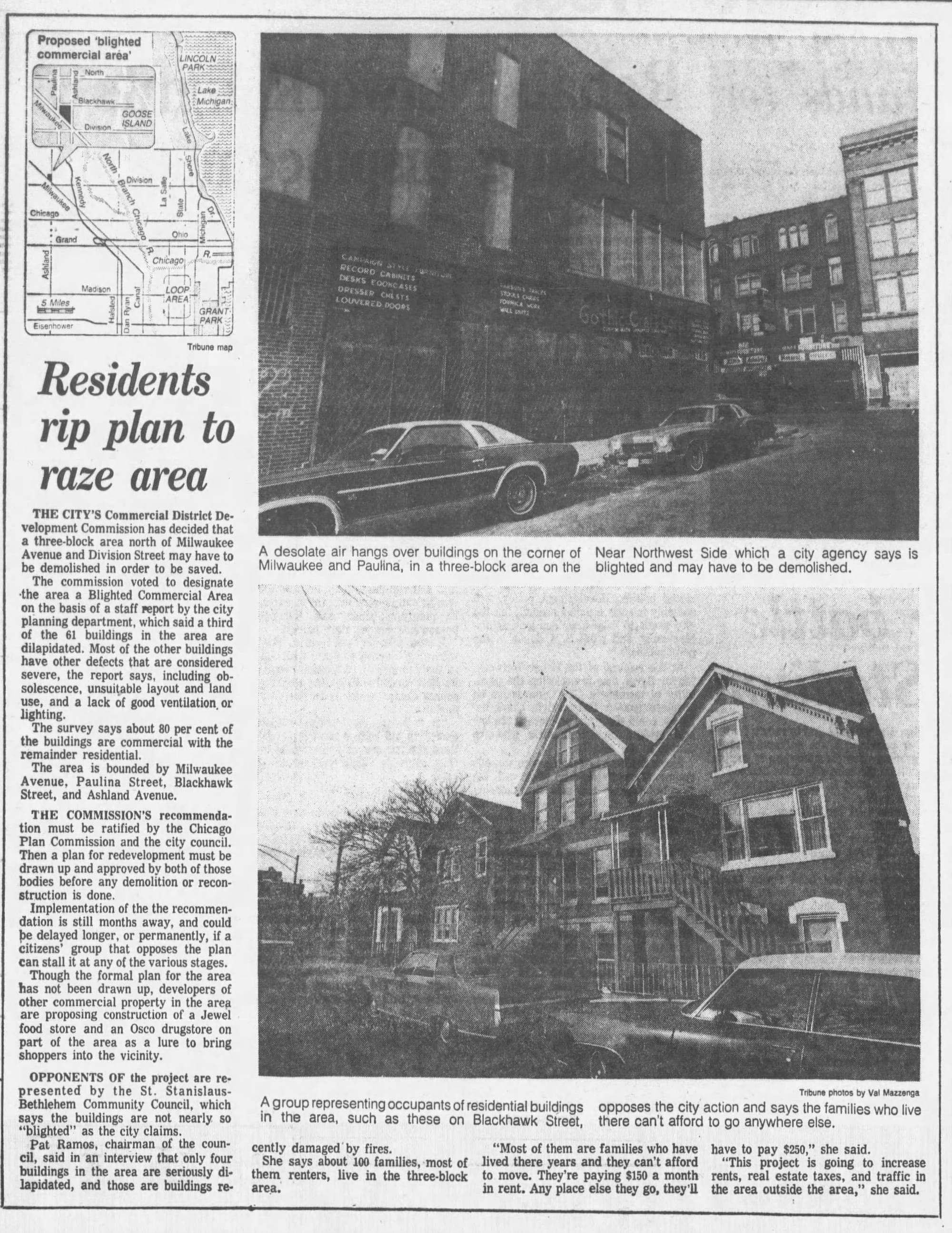

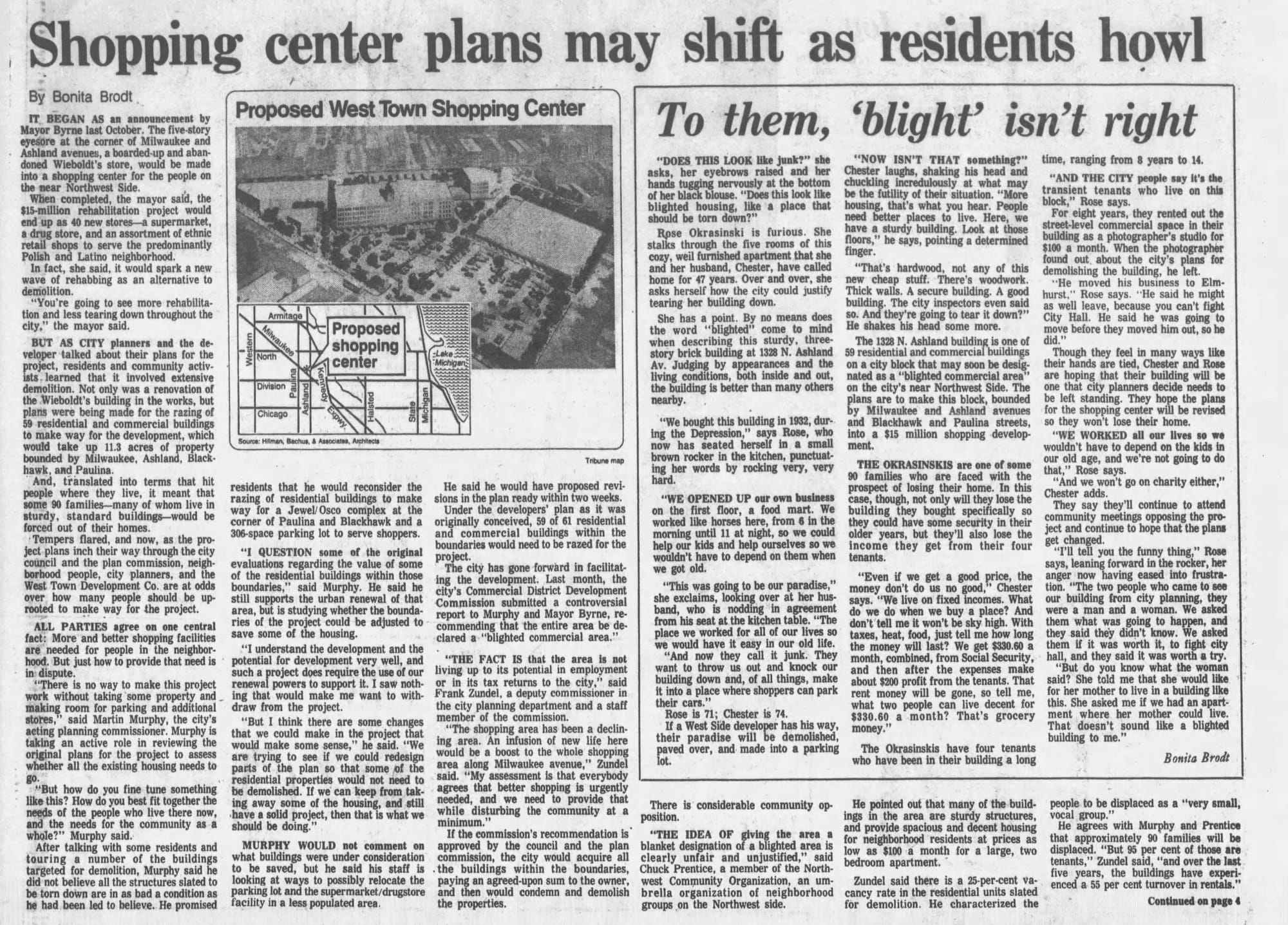

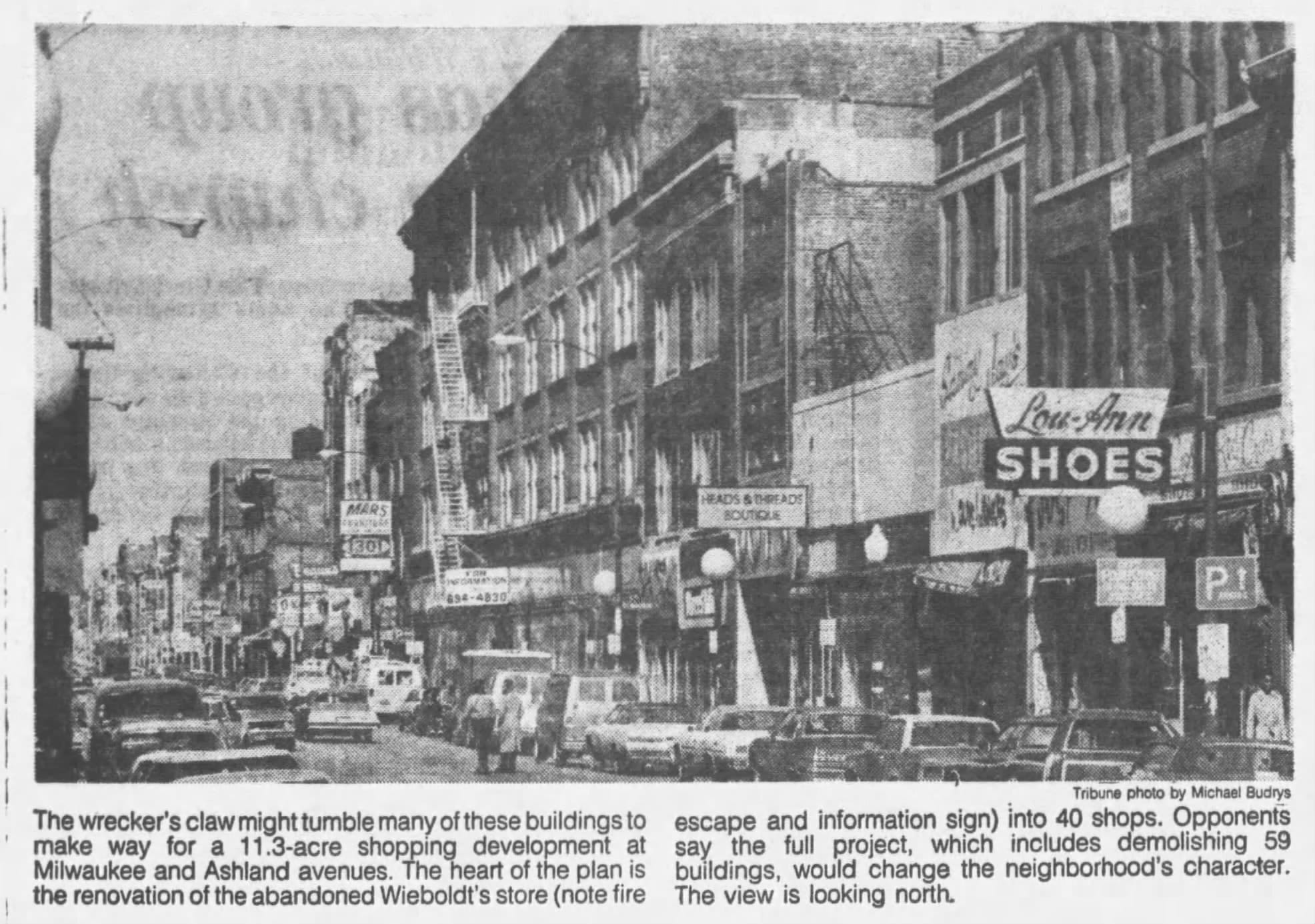

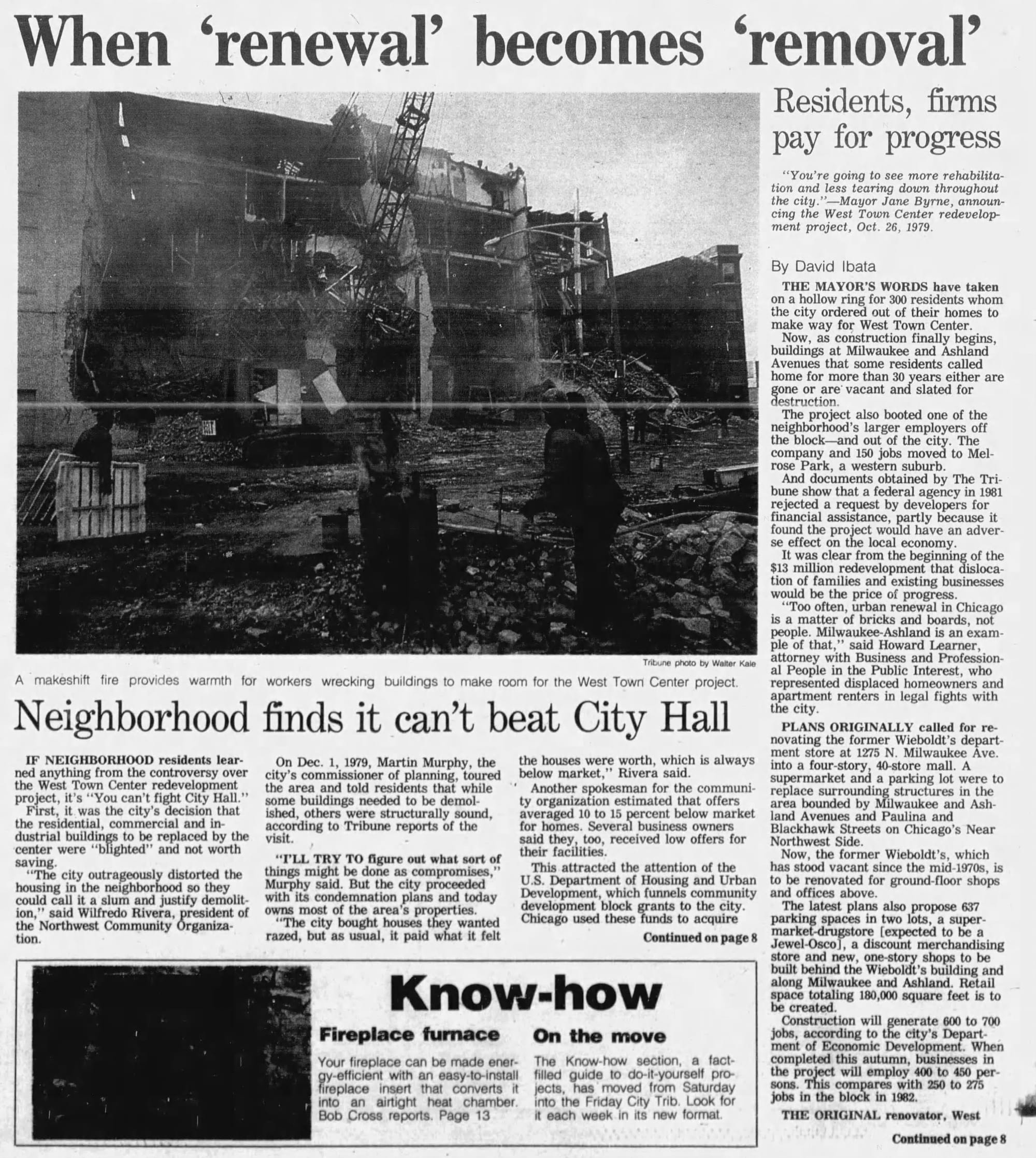

Wieboldt’s closure turned the building into a giant lifeless void on Milwaukee Avenue, and in response capital and government turned to their favorite mid-century tool—urban renewal. Flush with $3.7m ($17m today) in funding from the Department of Housing & Urban Development to condemn, acquire, and clear the site, a developer embarked on a $15m project to build “West Town Center”, renovating the empty Wieboldt’s building into a 40 store indoor mall, surrounded by hundreds of parking spaces and with a new, single-story shopping center. To pave the way for the development, the City of Chicago condemned 59 residential and commercial properties in the block bounded by Milwaukee, Paulina, Blackhawk, and Ashland.

1979 to 1983 articles about the urban renewal scheme that cleared the area around Wieboldt's and renovated the vacant department store

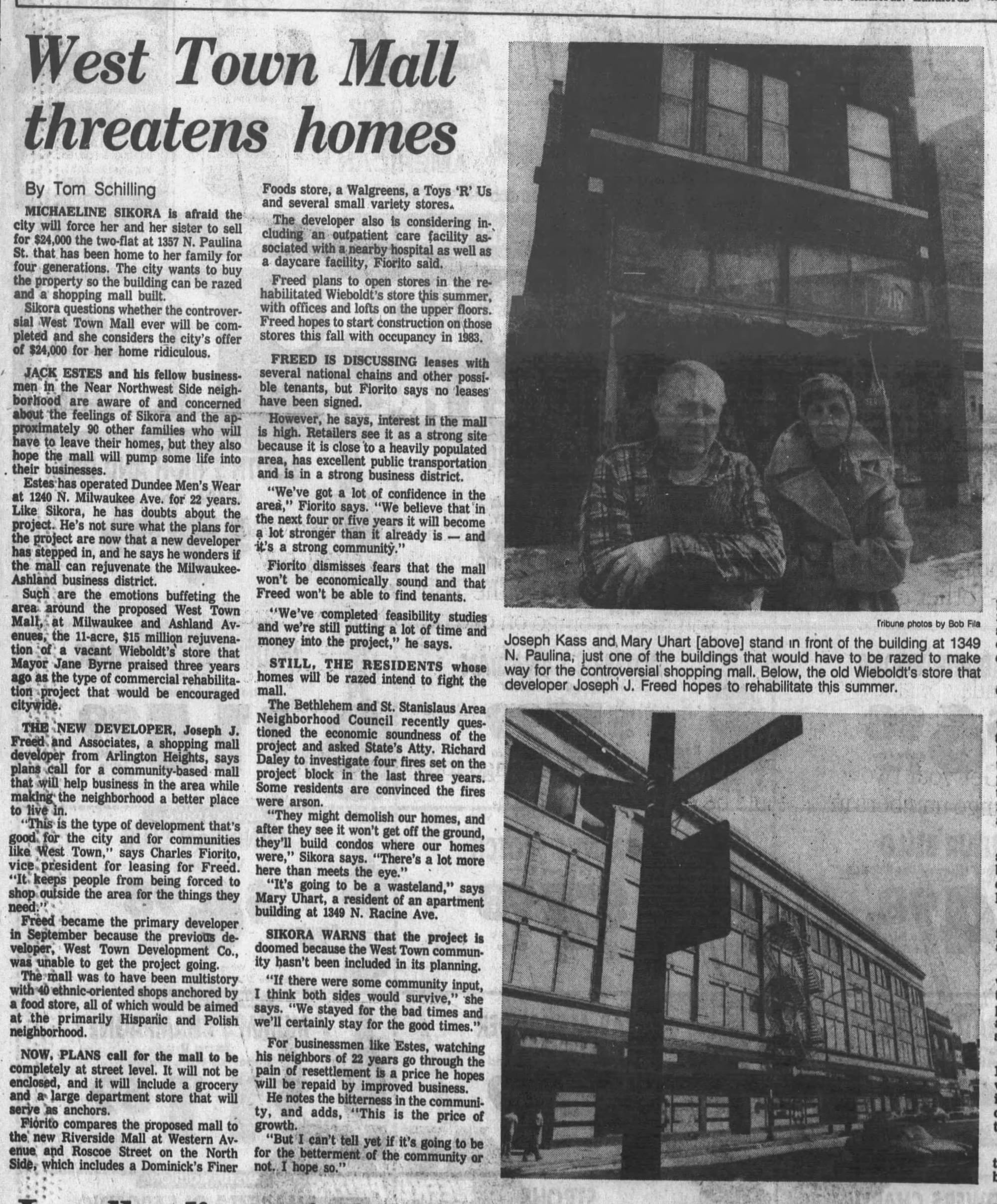

As you can imagine, the families who lived there didn’t agree that their neighborhood was blighted and didn’t want public money used to demolish their homes—they were pissed!

- “We’ve been here all our lives; we don’t want to move.”

- “It’s scary. What was just supposed to be a renovated building has snowballed into the removal of my house. I am stunned.”

- “Does this look like blighted housing, like a place that should be torn down?”

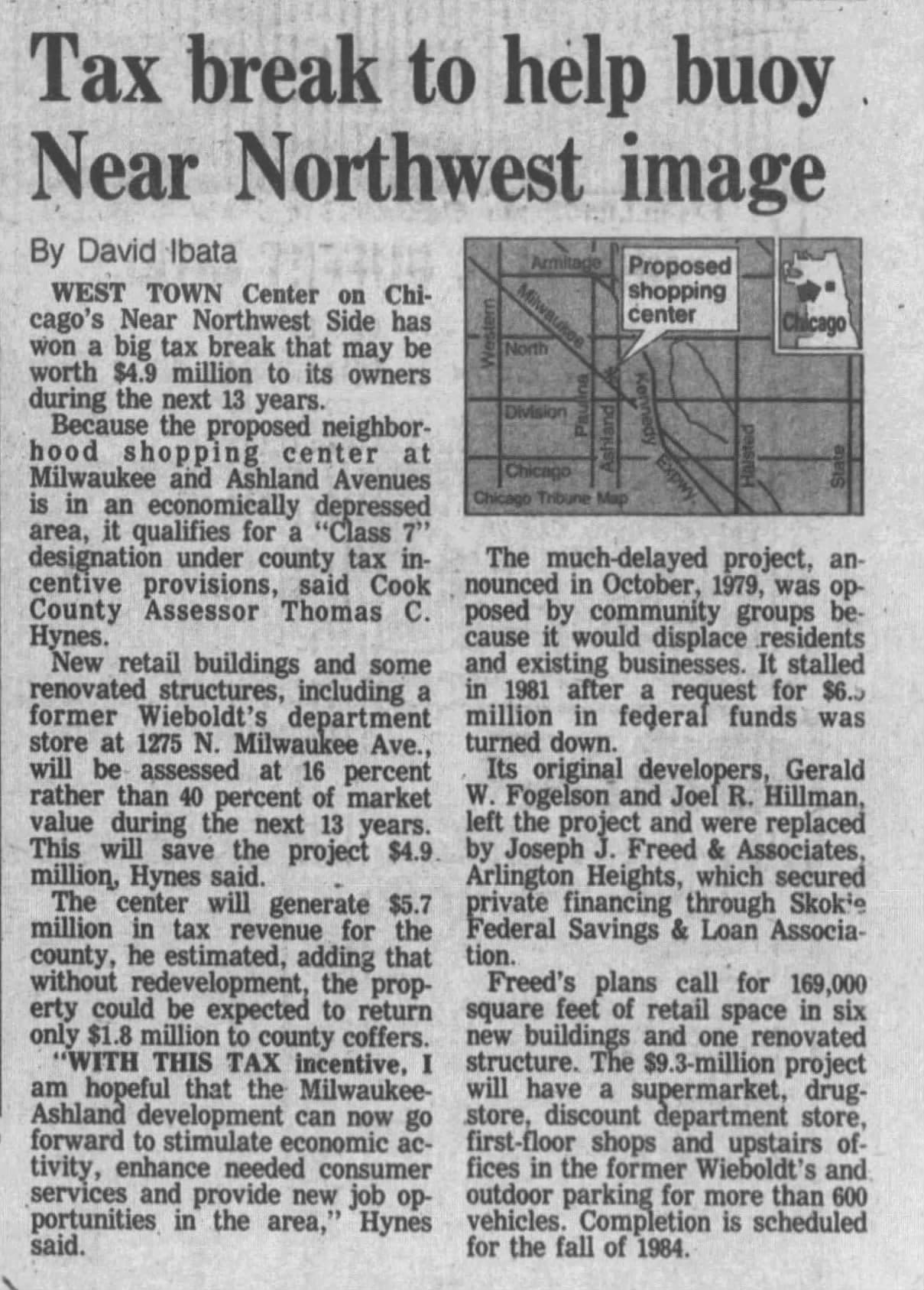

Equipped with the minimal tools they had, the residents fought the West Town Center project and the City of Chicago as loudly as they could. Vociferous opposition scared off the original developer, and potentially helped influence a grant application rejection by the Economic Development Administration, which denied the developer’s application because they forecast adverse local economic impact from the project. Still, armed with the money from HUD, $5m in tax breaks from Cook County ($16m in 2025 dollars), and supported by the Chicago Department of Planning, City and Community Development, the project—funded by Skokie Federal Bank and developed by Joseph J. Freed & Associates of Arlington Heights—went ahead. Owners of the condemned homes received market value for their properties, which in the early 1980s landed between $20k and $30k—the equivalent of $80k to $100k today.

...man, I’d be so angry if the city eminent domain'd my parents’ or grandparents' two/three flat in Wicker Park for $100k (a hundred-year-old home one block north on Paulina is currently for sale for $900k).

1886 - 2022

West Town Center forced more than 300 people from their homes to create a 637 car parking lot and a glorified strip mall. The indoor mall plan for the Wieboldt’s building fell apart, obviously, but the project did renovate the vacant old department store into offices, with first floor retail. Kind of a ridiculous return for $30m in (2025) public money, especially since it’s easy to imagine the cleared block bustling within 15-20 years as Wicker Park gentrified in the 1990s and 2000s.

The Wieboldt’s building was included as a contributing structure to the Milwaukee Ave Landmark District, designated in 2007. Centrum Partners acquired West Town Center, including the Wieboldt’s Building, for $33m in 2011. Potbelly, Pet Supplies Plus, and Vitamin Shoppe all opened in the building in 2014, and the upper floors were converted into self-storage in 2017—a functionally dead use for a space that was once very much alive.

2025 photos

Production Files

Further reading:

- Milwaukee Avenue District Landmark Designation Report

- “Bringing ‘Downtown’ to the Neighborhoods: Wieboldt’s, Goldblatt’s, and the Creation of Department Store Chains in Chicago.” by Richard Longstreth in Buildings and Landscapes, 2007

- 1960 Shareholders Report

Cracking up at how shitty the lion logo originally was.

Two 1898 ads, one with a hilariously badly drawn lion and the other with a more normal depiction of a lion

Articles from the fire salvage sale.

1898 fire salvage sale ads

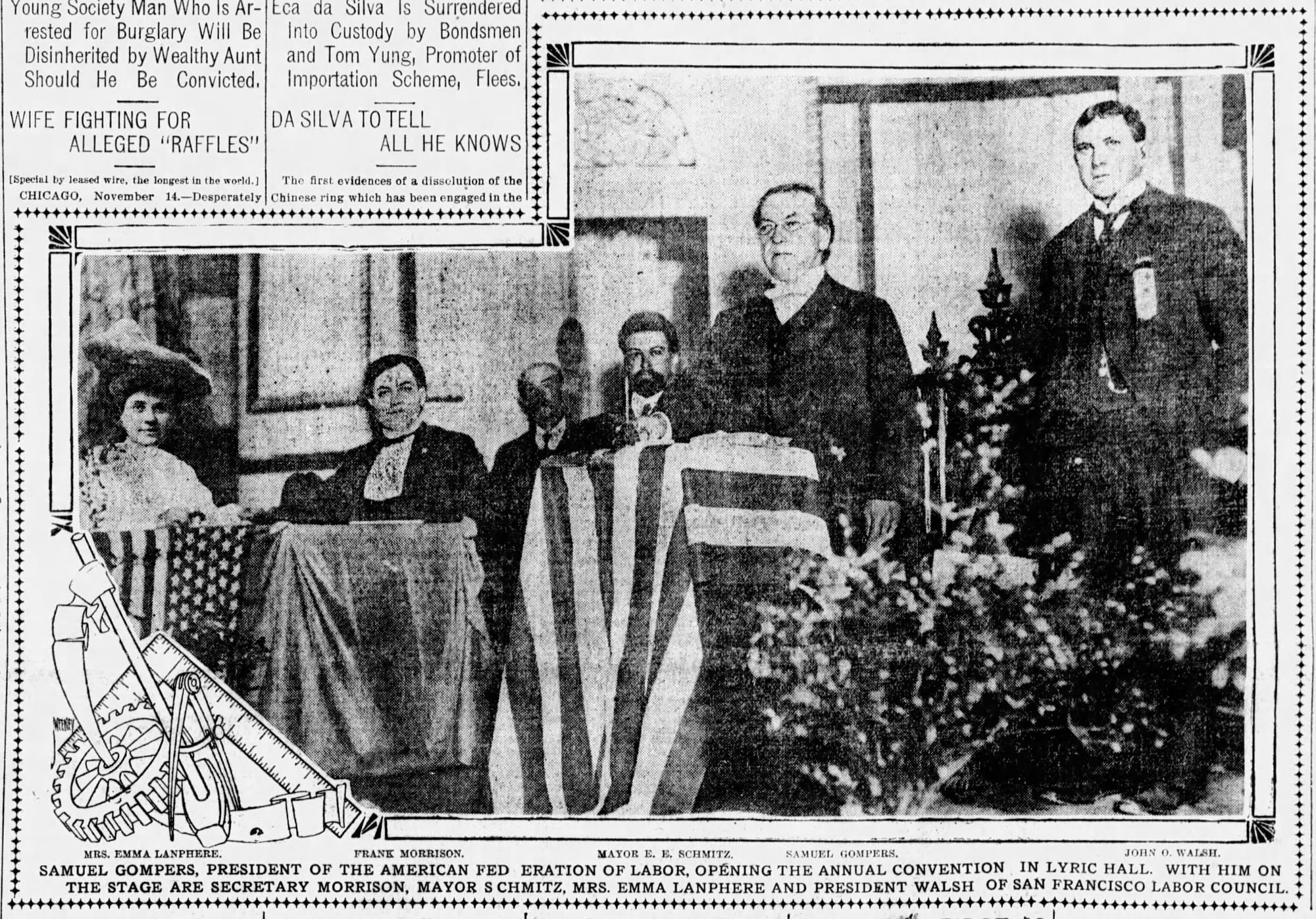

Emma Lanphere, the union organizer, seems like she was an impressive lady.

1904, Emma Lanphere in San Francisco with labor leaders including Samuel Gompers

Six weeks after the fire, W.A. Wieboldt bought the land that the burned store stood upon.

Within a few weeks of that, he had a building permit.

And less than two years later he'd bought the land and pulled a permit for the first addition.

1886 fire insurance map | 1892 fire insurance map | 1914 fire insurance map | 1938 aerial, Illinois State Geological Survey | 1950 fire insurance map | 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985 aerials, Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning Imagery Explorer

Where I took the photo from.

Member discussion: