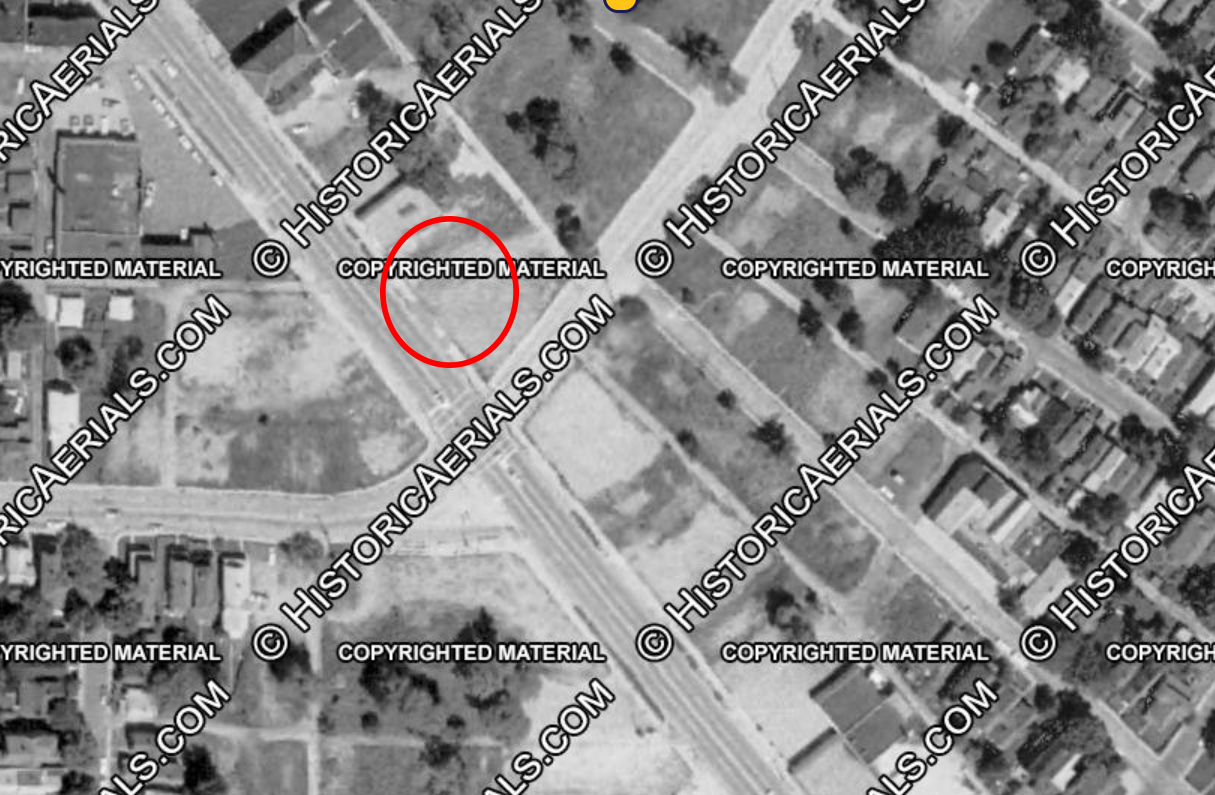

Where you could once see bands like Bill Black’s Combo and get a bite to eat until 4am, you can now...uhhhh, huff exhaust fumes? This stretch of Fountain Square was, of course, bulldozed for highways. With the federal government shoveling money at the states, encouraging them to sacrifice their urban areas on the altar of cars — the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act covered 90% of states’ highway-building costs — the former Ban-Dee Restaurant & Lounge was razed when the Indiana State Highway Commission dropped the I-65 and I-70 interchange on the neighborhood. The building was one of more than 8,000 demolished for the highways that carved up Indianapolis, displacing more than 17,000 people.

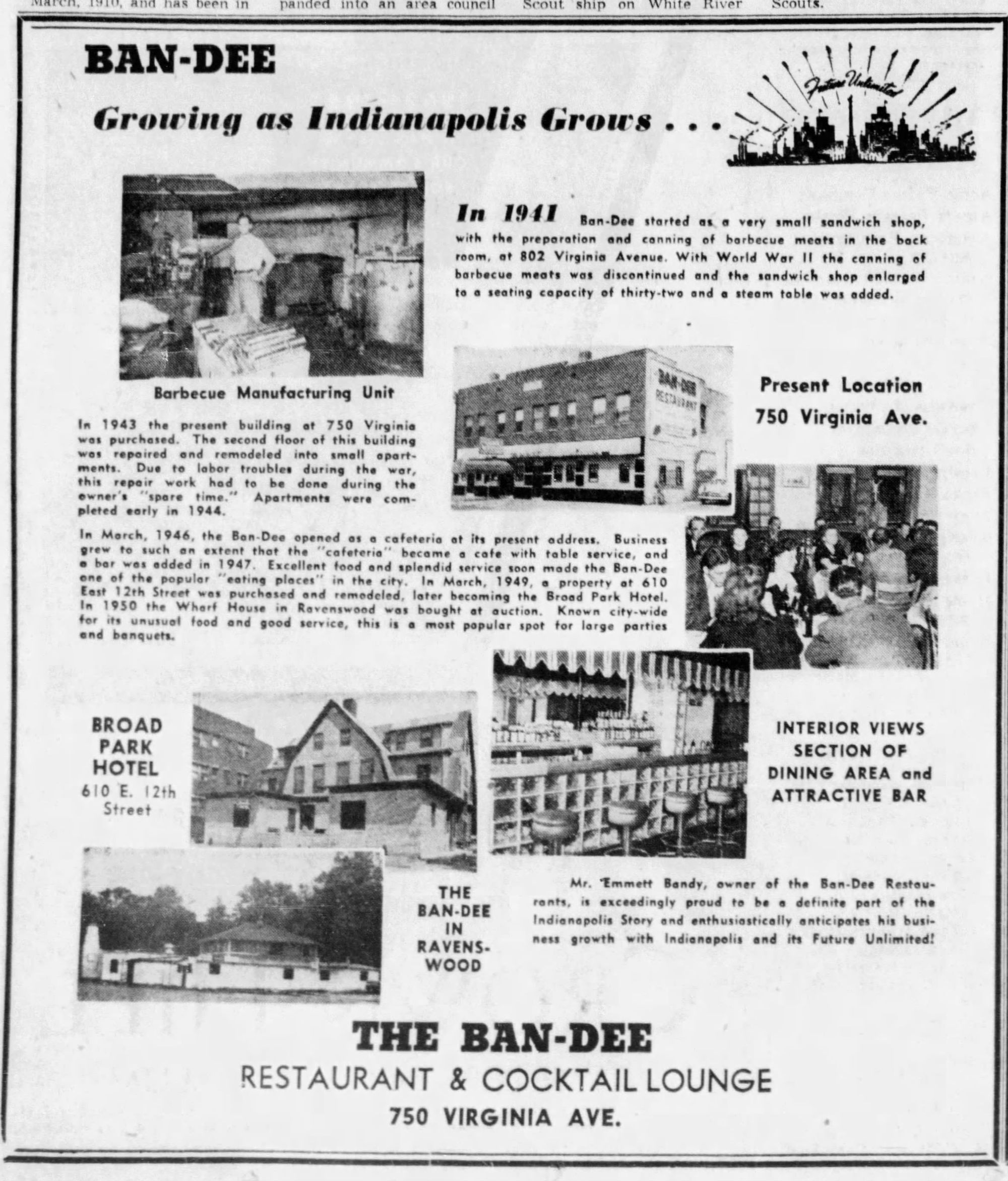

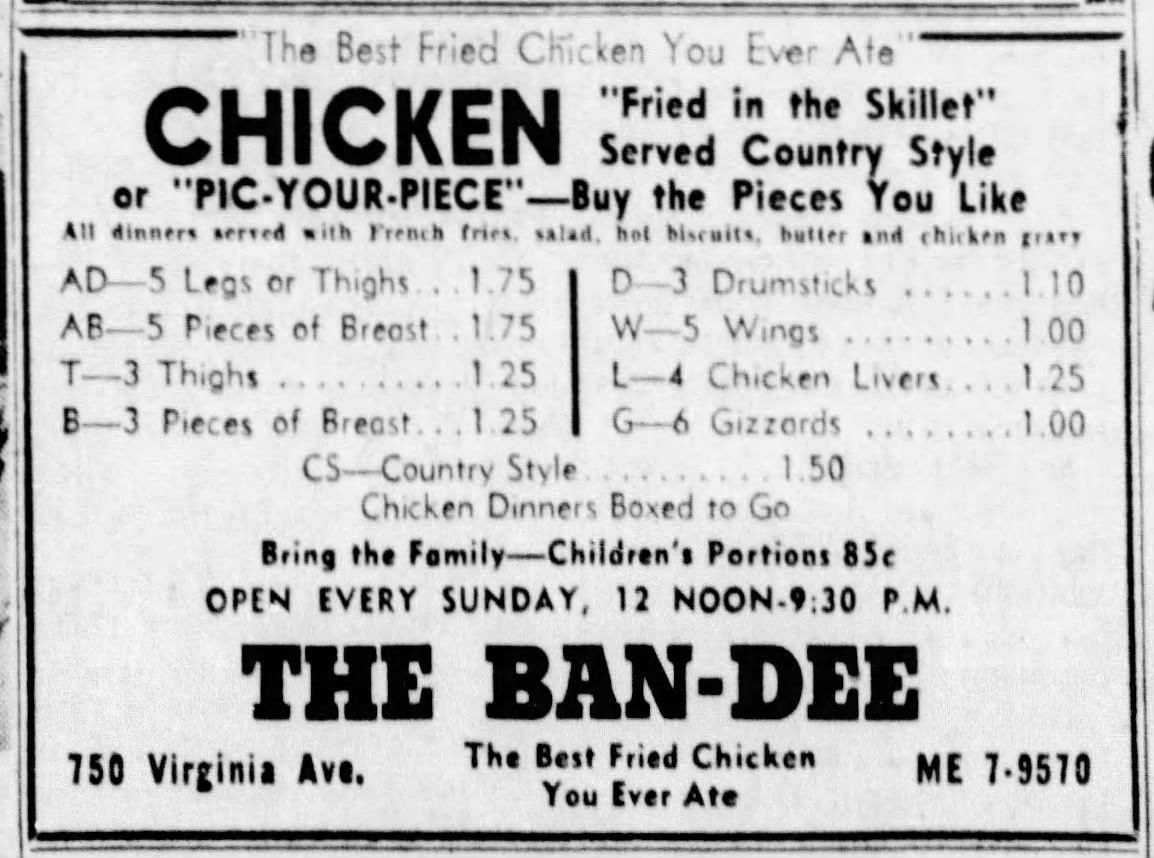

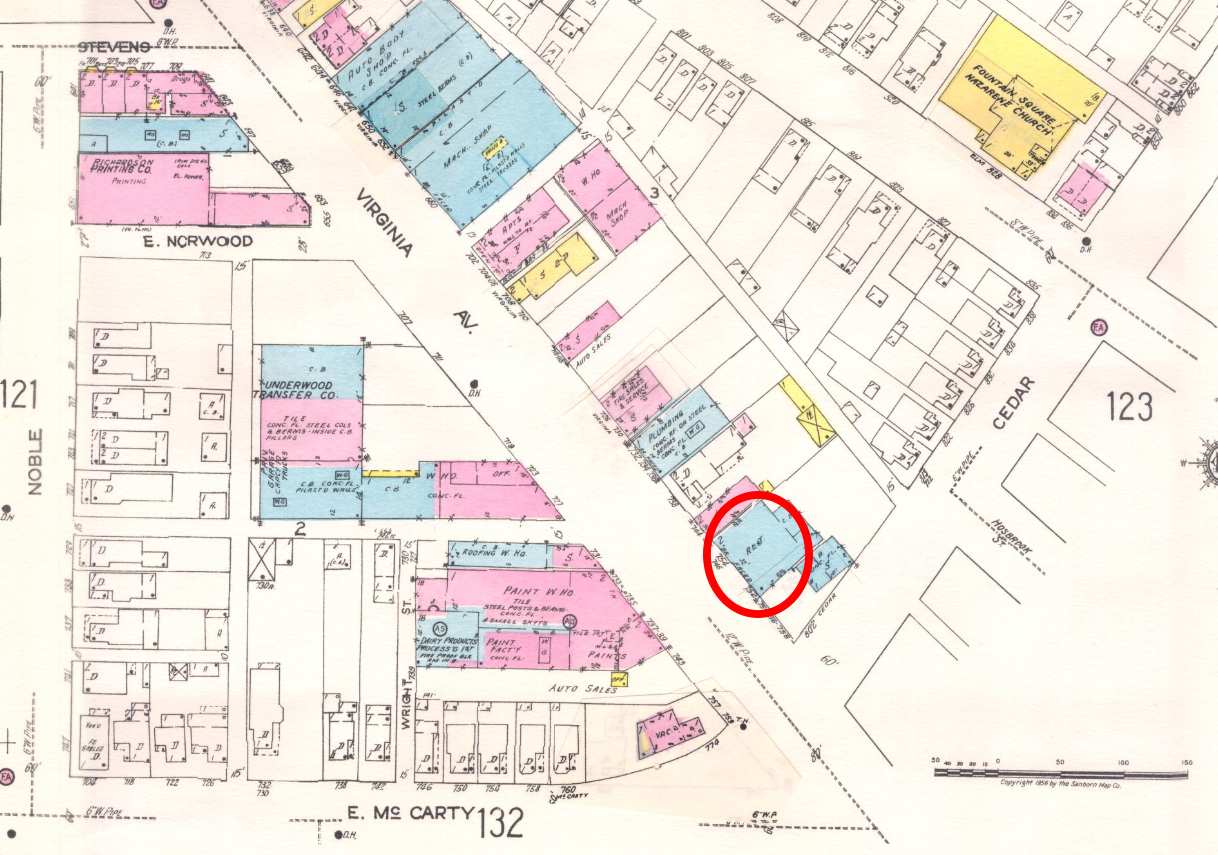

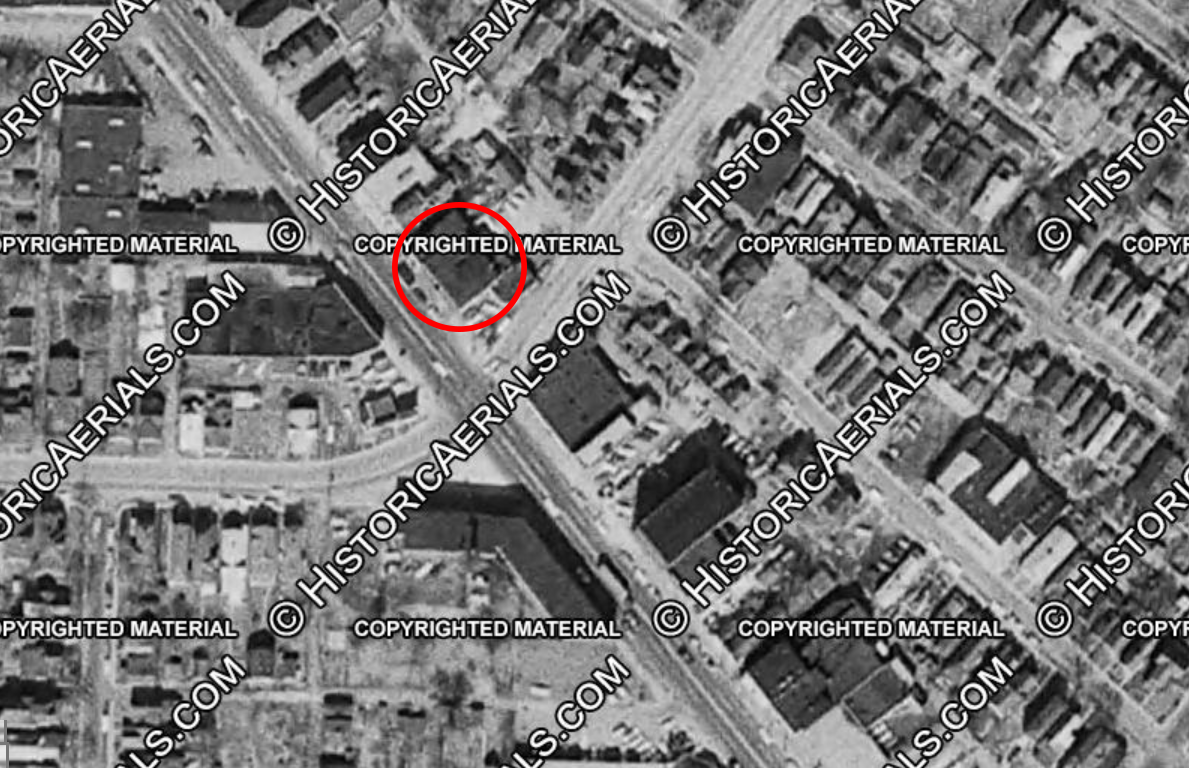

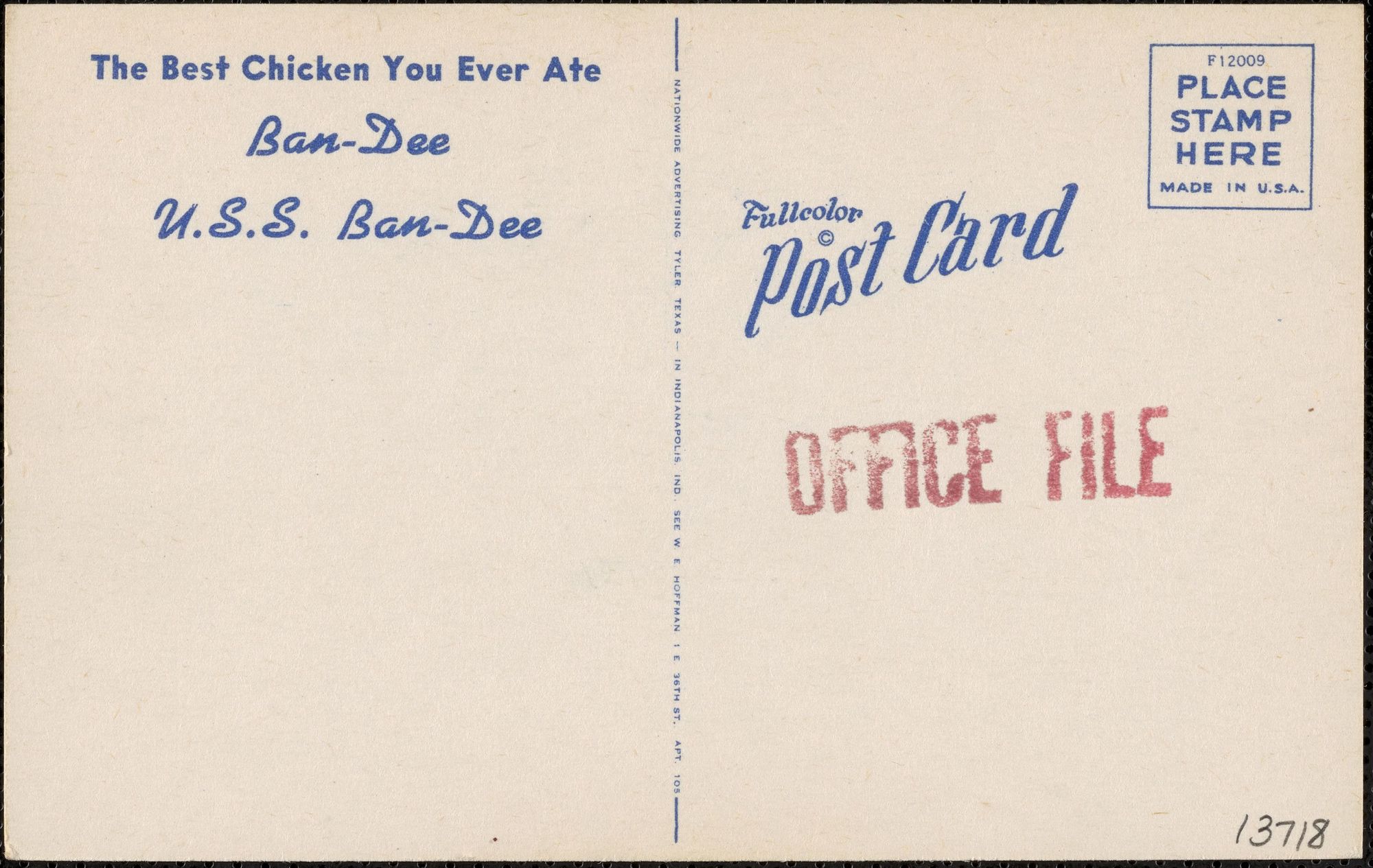

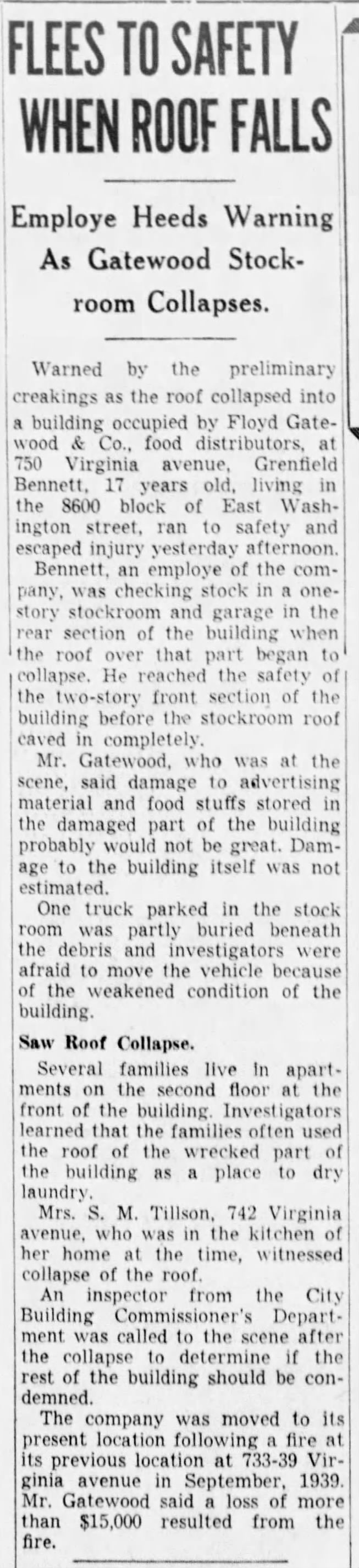

Before that, though, the Ban-Dee was a fried chicken joint. Named for its owner, Emmett Bandy, the Ban-Dee began(-dee?) as a sandwich shop nearby. Emmett Bandy bought this building in 1943, converted the upper floor into apartments, and opened the Ban-Dee Restaurant here in 1946. The apartments above rented for $14.50 a week in 1960, roughly equivalent $580 a month today. For a time, before Ban-Dee opened, the building had been home to a car dealership, which makes its fate — demolished for a roadway — a little ironic.

The Ban-Dee closed in 1964. Clubs with late night kitchens briefly followed: Castaways Club, then New Frontier Club. I have to imagine there are barely any Indy music venues today with a kitchen open until 4am, but both Castaways and New Frontier fit that bill. They had weekly jam sessions, go-go girls, and a stage graced by bands like Bill Black’s Combo, who were founded by Elvis’ bassist and opened for the Beatles on their first US tour. Granted, by the time Bill Black’s Combo played here in 1965, Bill Black himself was dead and the prestige of the omnipresent but ever-rotating Memphis group was on the decline.

By 1965 though, the building’s death warrant had basically been signed. Opposition to Indianapolis’ highway plans built over the course of the 1960s, but in reality the state had determined their fundamental routes by 1961. So protests were more of a rearguard action - an unwinnable battle, but one that groups like the Homes Before Highways Commission, Livable Indianapolis for Everyone, and the Indianapolis Taxpayers Association fought anyway. In opposing the penetration of the interstate into the city, they argued that suburbanites did not have the right to demand highways into the inner city that would destroy 5,000 dwellings, since they did not pay taxes…which, amen.

Like literally everywhere else in the US, highway construction in Indianapolis disproportionately damaged Black neighborhoods, already devalued by redlining and disinvestment, making land acquisition for highways cheaper. As it organized to fight the destruction of neighborhoods, Indianapolis’ African-American community threatened to organize a march with Martin Luther King Jr. to protest highway displacement. Indiana congressman, Voting Rights Act co-author, and all-around mensch Andrew Jacobs Jr. also got involved, introducing a federal Homes Before Highways bill, which aimed to “prohibit the acquisition of land or construction of public works until adequate and comparable replacement homes and churches are available to the displaced”.

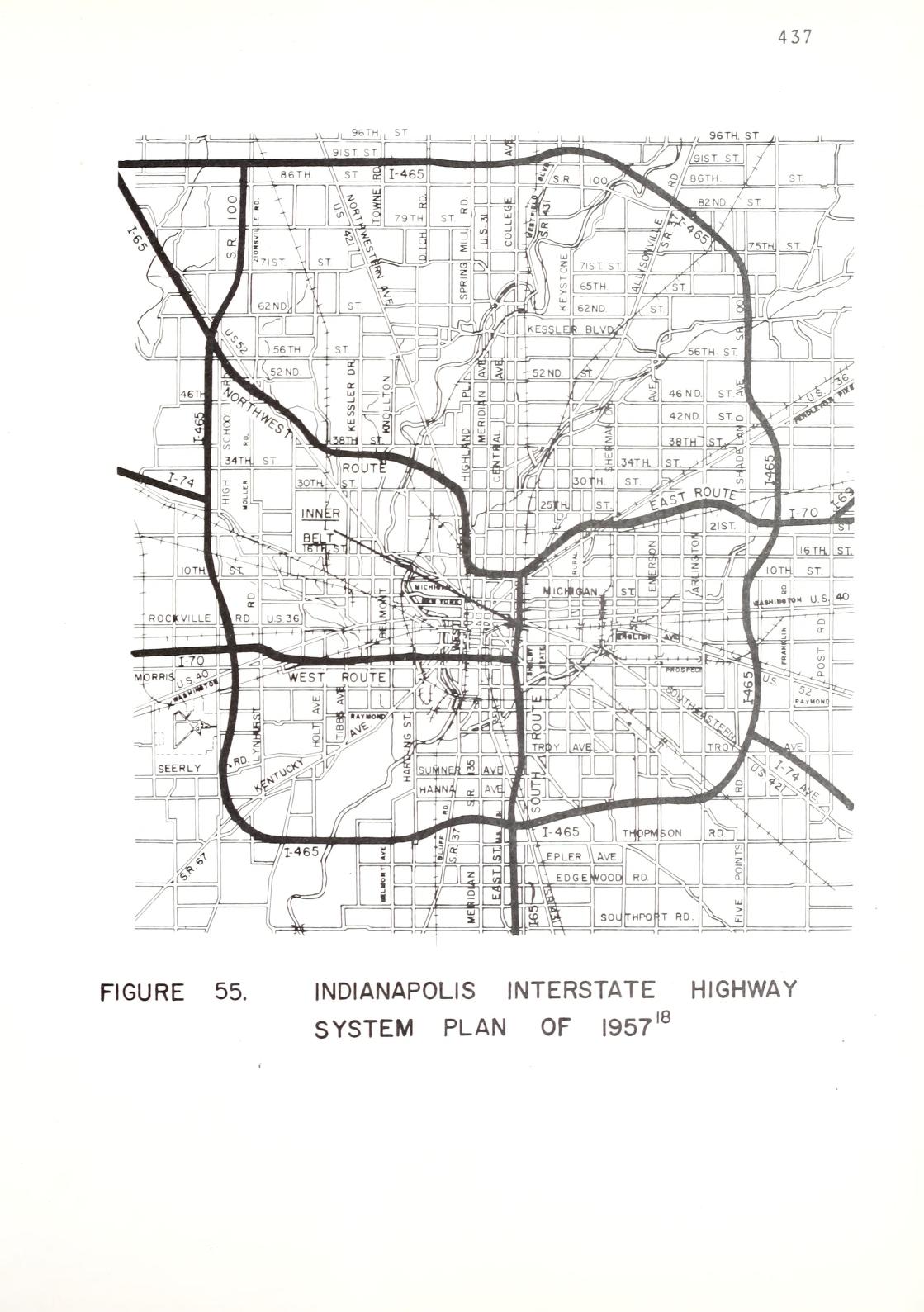

The gears of the state, in motion for years since the first Indiana interstate plan was proposed in 1957, were dead set on routing the interstates through the city, but the organized opposition did eke out minor victories at margins. In 1967, their pressure led to the passage of Indiana House Bill 1347, which increased relocation payments to $5,000 over ‘fair market value’ and provided for “relocation assistance including loans of up to $2,500”.

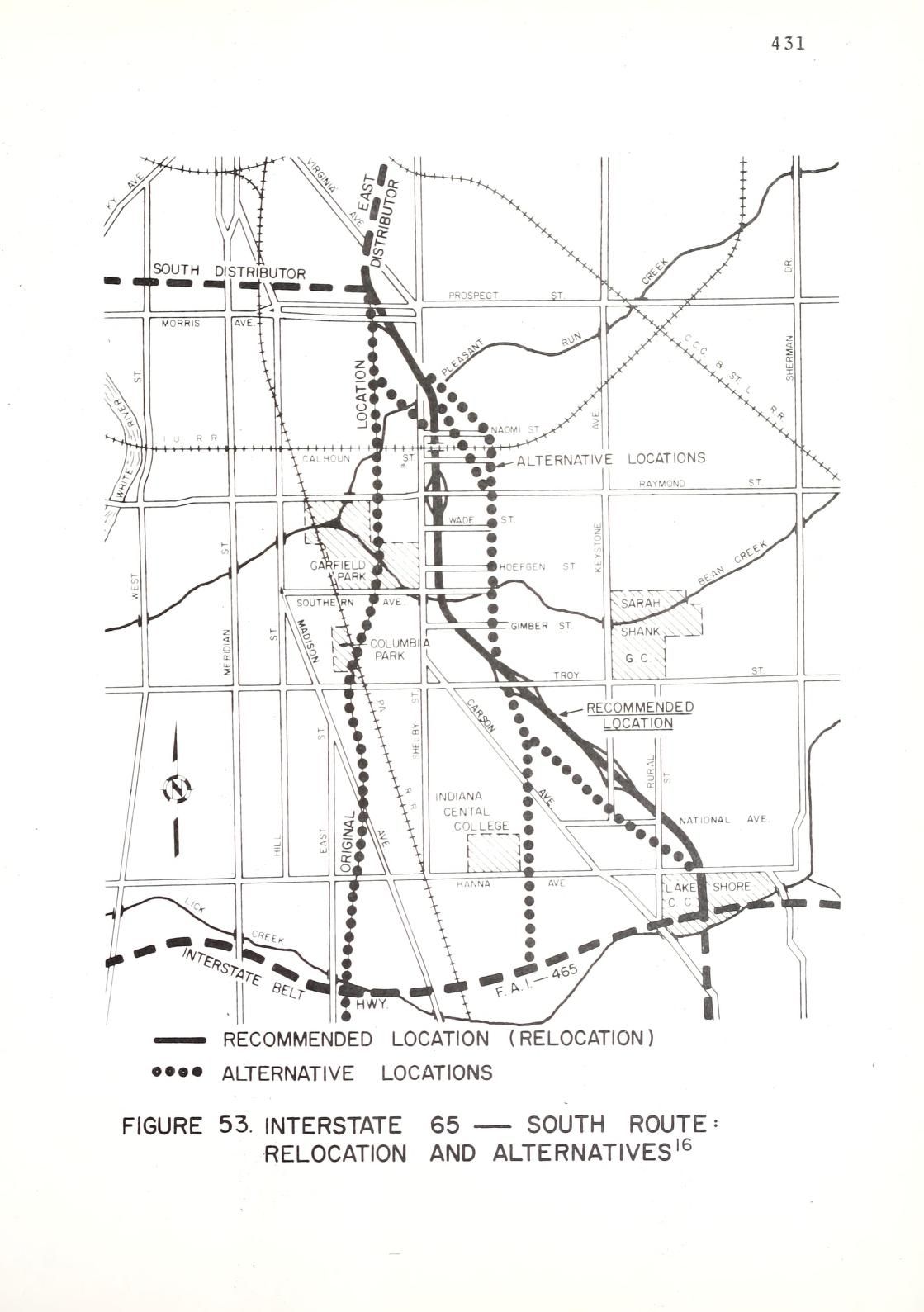

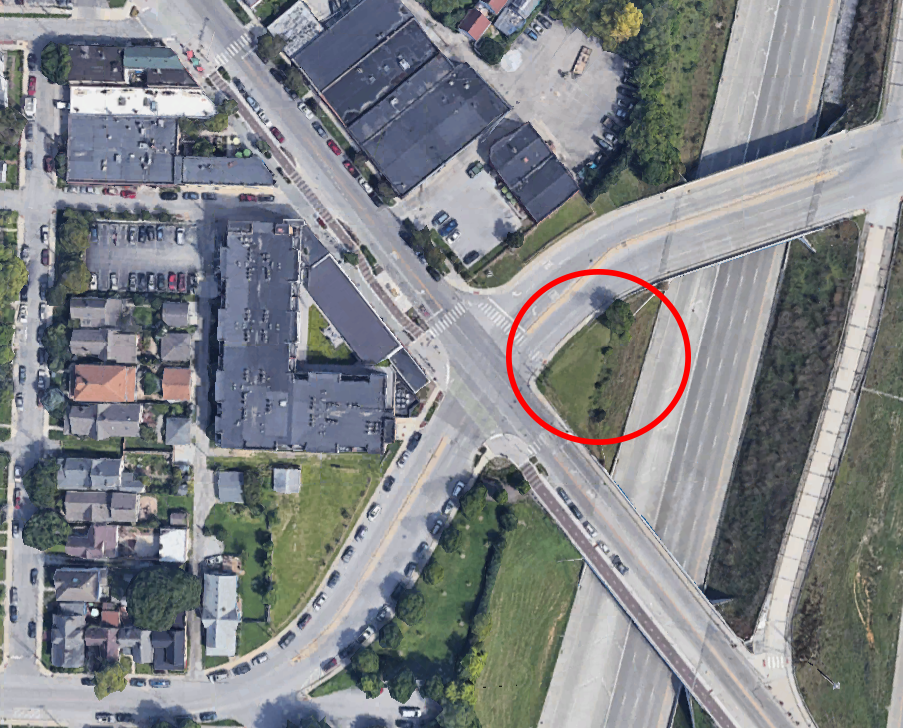

The Ban-Dee building never really stood a chance, though - the Indiana State Highway Commission always intended for the “Southeast Inner Belt Master Interchange'' to land here. The state perceived limited location options for the interstate they just had to build - avoiding St. Patrick's church to the south was a must, they didn’t want to completely blow up the shopping areas of Fountain Square and Virginia Avenue (...although the subsequent population loss would do that anyway), and any alignment had to miss Garfield Park to the south. So its fate long since decided, sometime in the late 1960s this little club was demolished.

Production Files

Further reading:

- In 1975, the Indiana State Highway Commission put out a (very early, quite incurious, but definitely exhaustive) History of the Interstate System in Indiana

- A good read on "How interstates divided Indianapolis neighborhoods and displaced 17,000 people", with a focus on the south side of the city

- IUPUI Professor of Anthropology Paul R. Mullins has done good work on racism and the interstates in Indianapolis, as well as the Homes Before Highways Commission and the protests around the building of the interstates

- A neat read on Bill Black's Combo, who I had never heard of but seem vaguely Forrest Gumpy in the way they pop in and out of the stories of some of the biggest bands in the 1950s and 1960s

Member discussion: