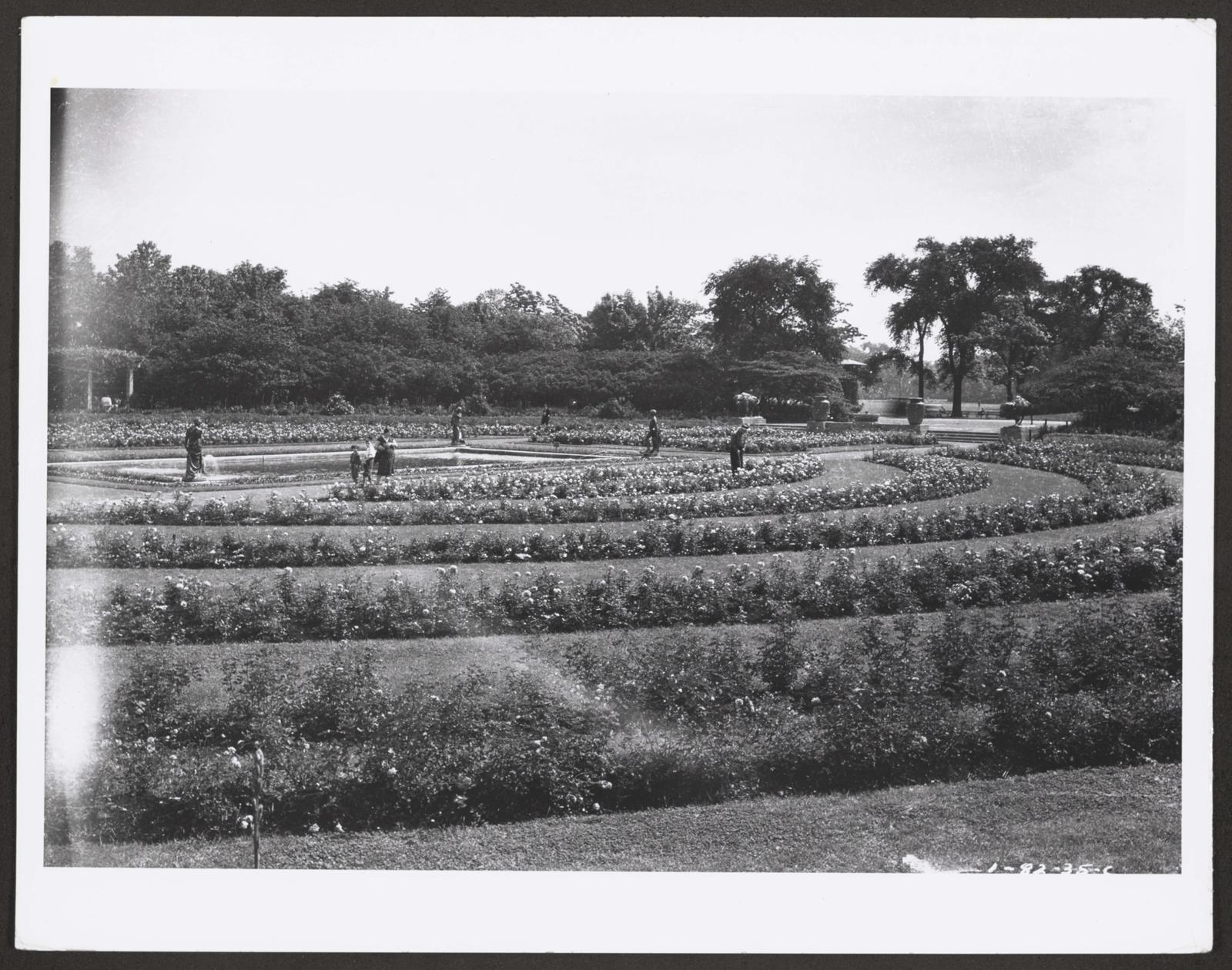

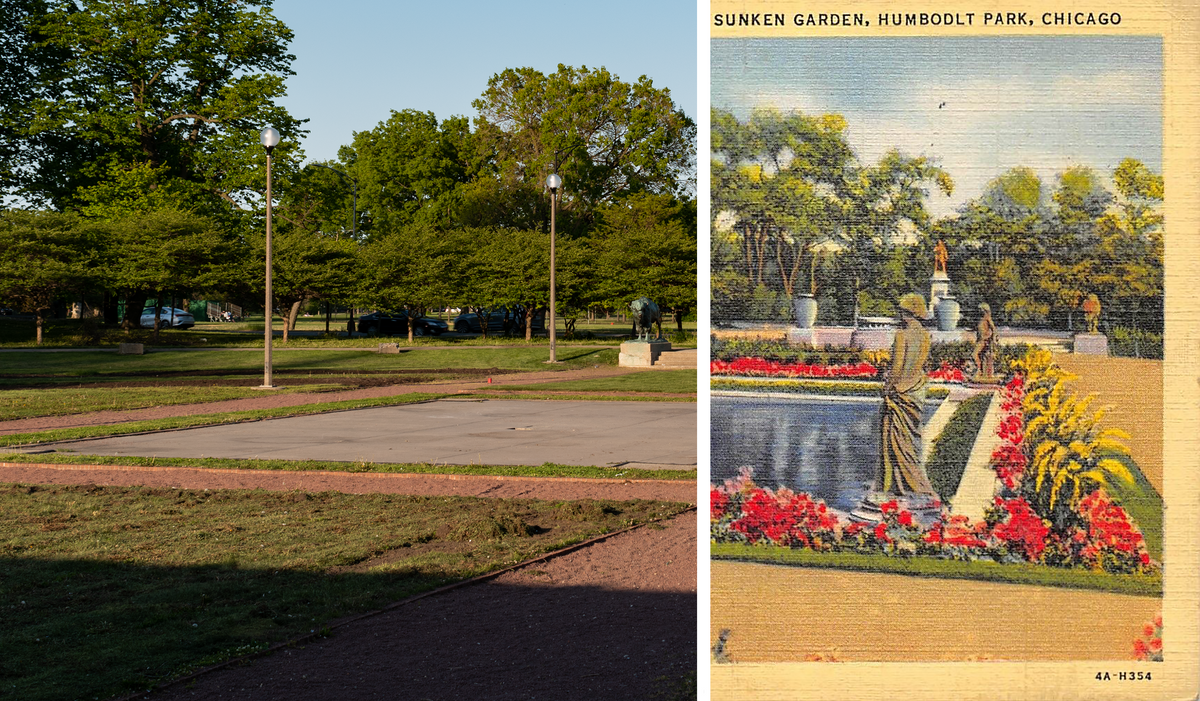

One of Jens Jensen’s least favorite works, he called Humboldt Park’s sunken formal garden “a folly of my youth”–and that was before half a century of neglect filled in the water court and ripped up the flower beds.

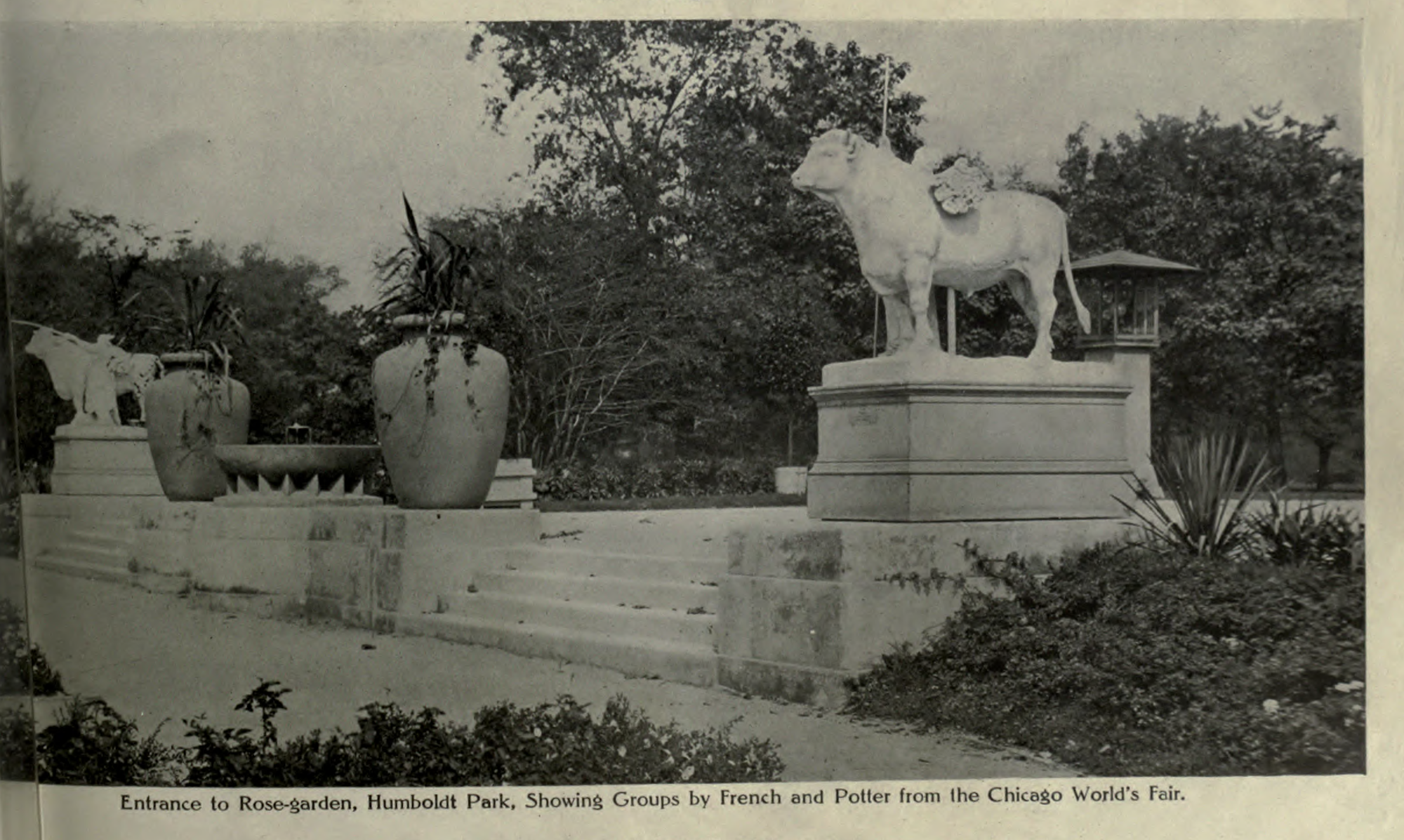

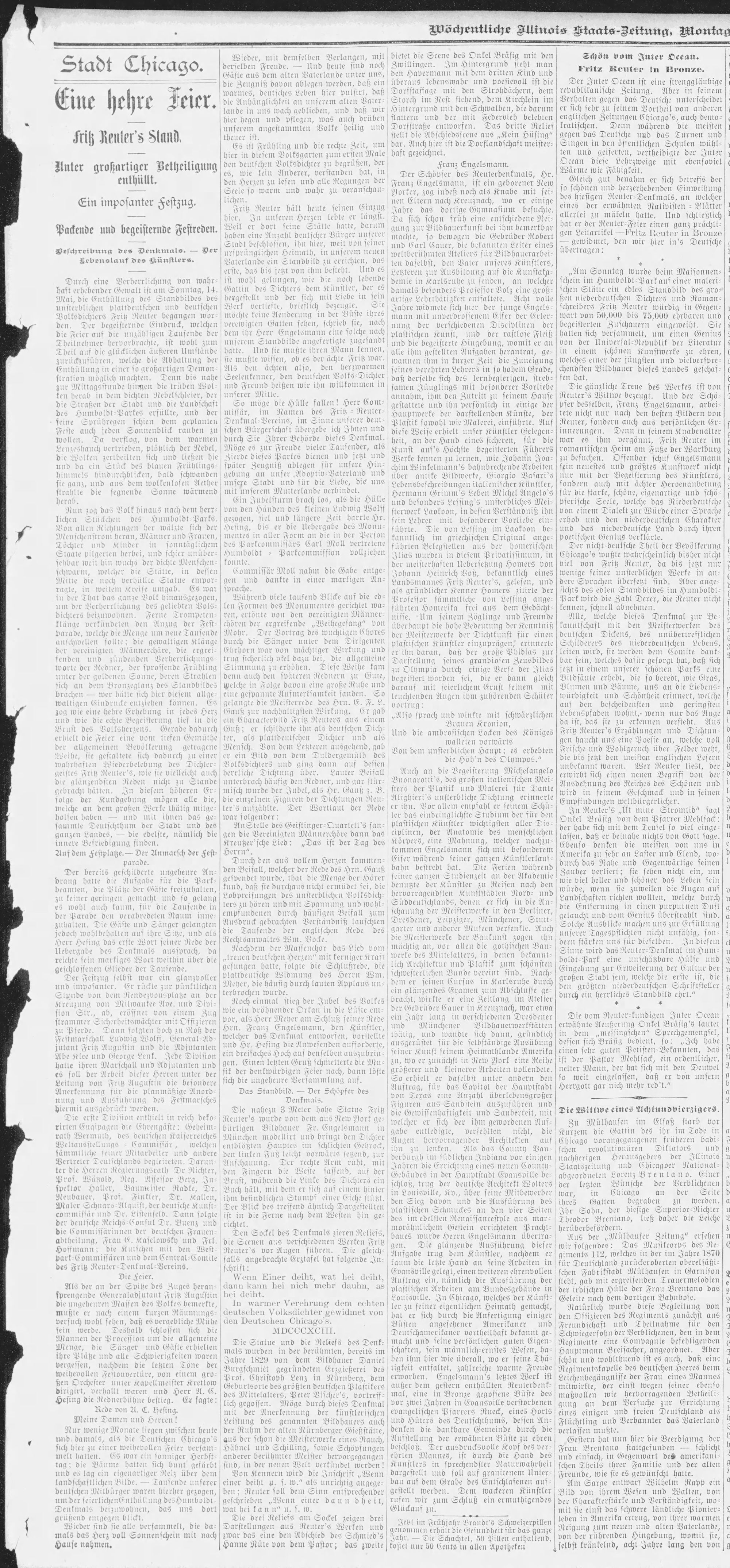

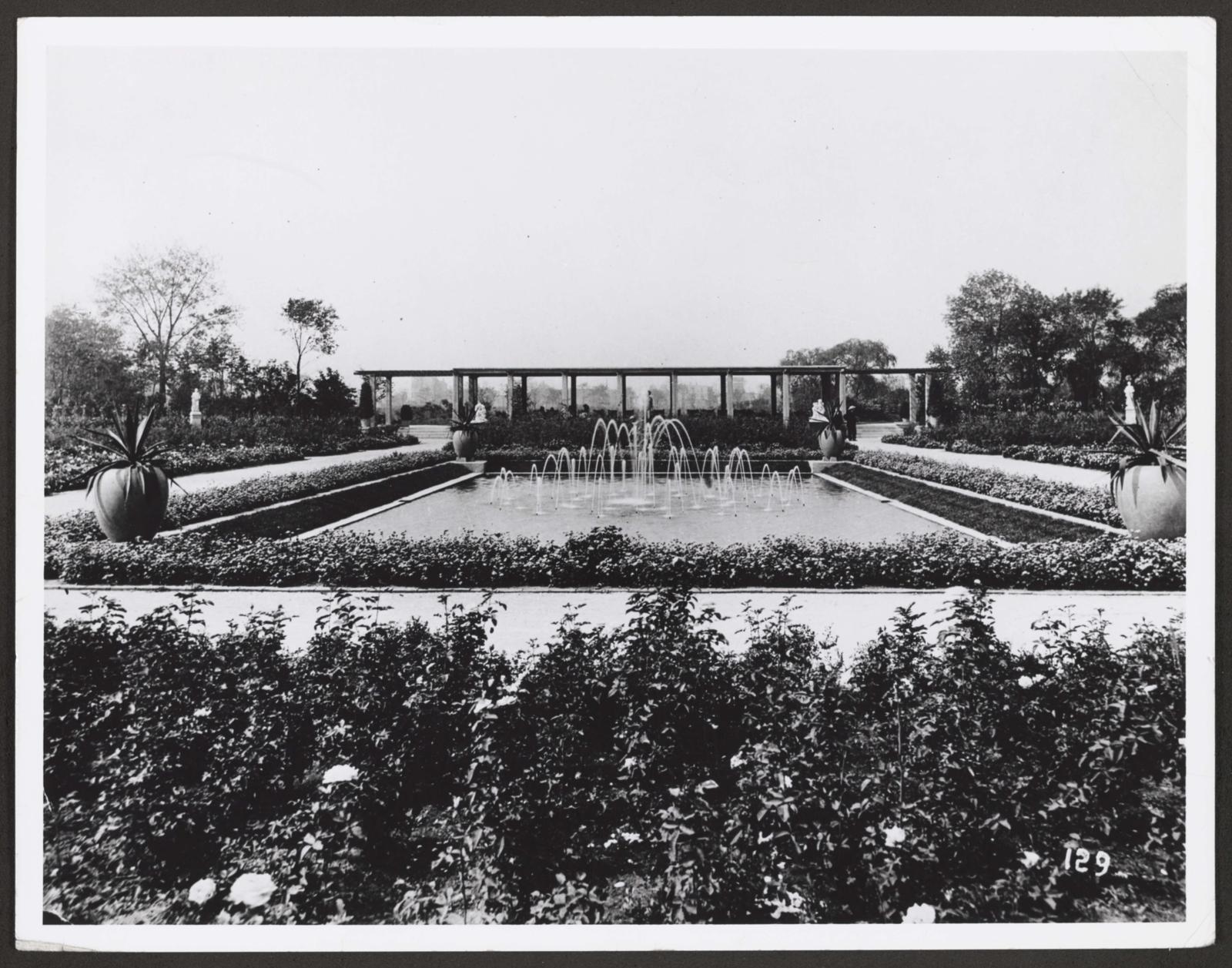

Let's tally up the damage from those decades of neglect: the big green Teco ware urns? They disappeared between the 1950s and early 1960s. Those bronze fountains ringing the water court? Removed in ~1950 and installed in Grant Park in 1964. The water court itself? Filled in around 1952.

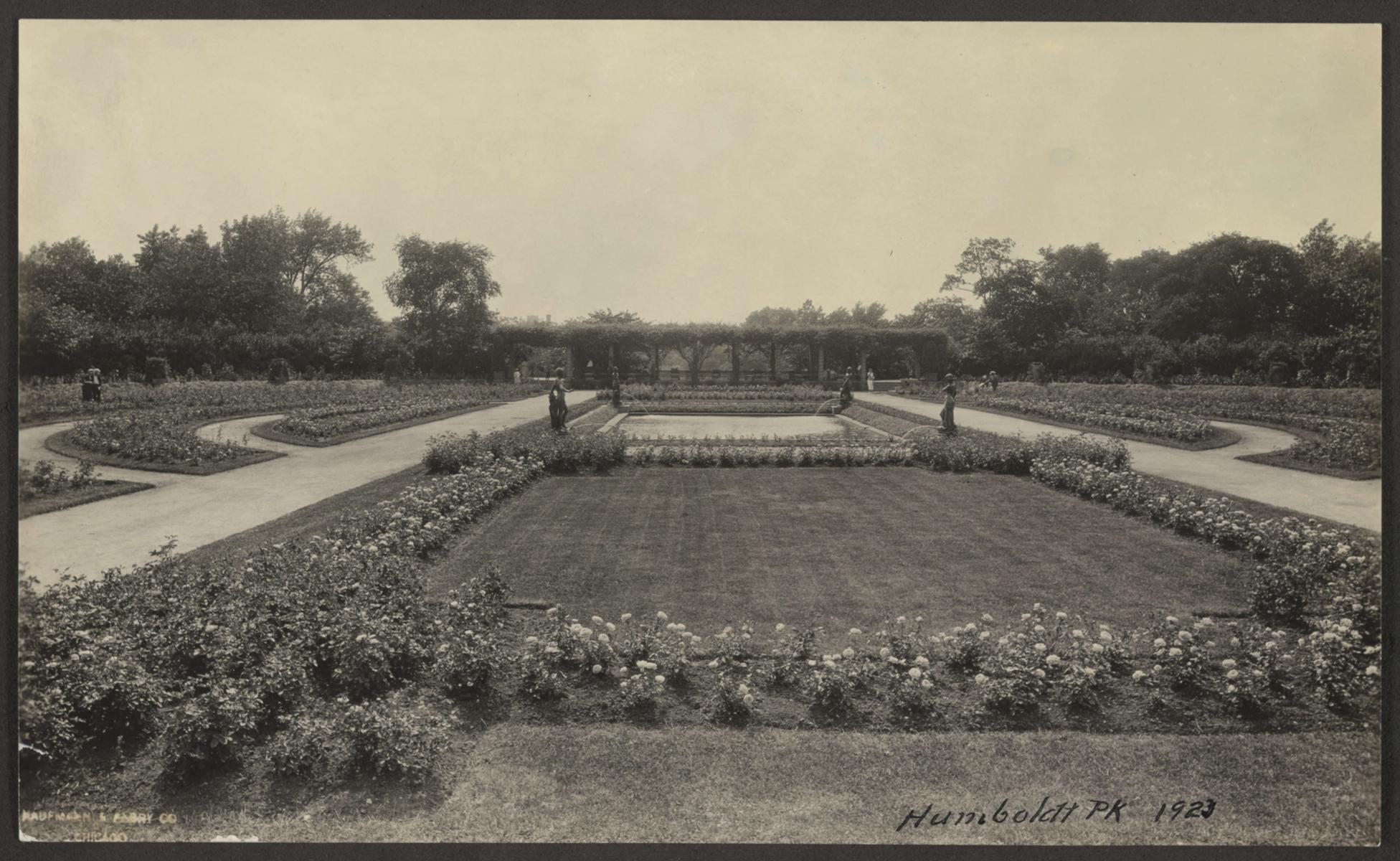

While not visible in the postcard, those Prairie Style lanterns were there–the park was so lush that they weren't always visible from the Sunken Garden. The sparser foliage hints at another major change that may've contributed to the garden's decline–a 1936 Works Progress Administration project straightened the drive through Humboldt Park, bringing the road and all its accompanying fumes, debris, and asphalt closer to the Sunken Garden.

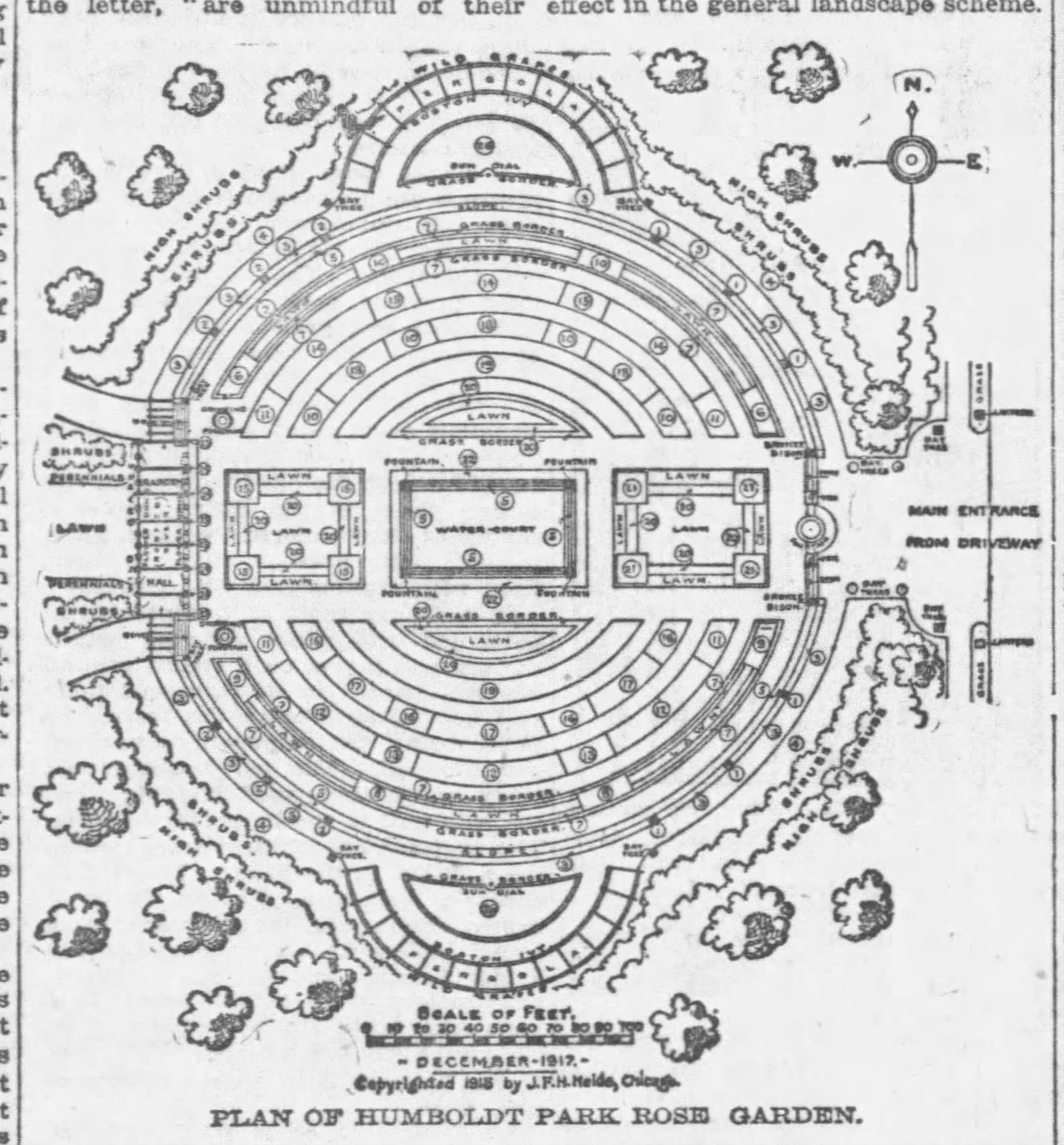

Originally a formal rose garden, the Sunken Garden here was part of Jens Jensen’s complete redesign of Humboldt Park, launched in 1905 after he was appointed General Superintendent and Chief Landscape Architect of the entire West Park System (the Chicago Park District used to be split in three). The Sunken Garden replaced the Fromann & Jebson-designed Humboldt Park Conservatory that once stood on this site.

A formal garden is an odd fit for a landscape architect who built his reputation creating naturalistic parks bursting with native plants–explains why he wasn’t especially fond of it in his later years–but Jensen was still experimenting with his design philosophy, and some of that ethos shone through anyway (at least for a while). A contemporary publication called it “Prairie style executed in the formal manner”, and Jensen pointed out that he "put hawthorns at the entrance to suggest the meeting of woods and prairie".

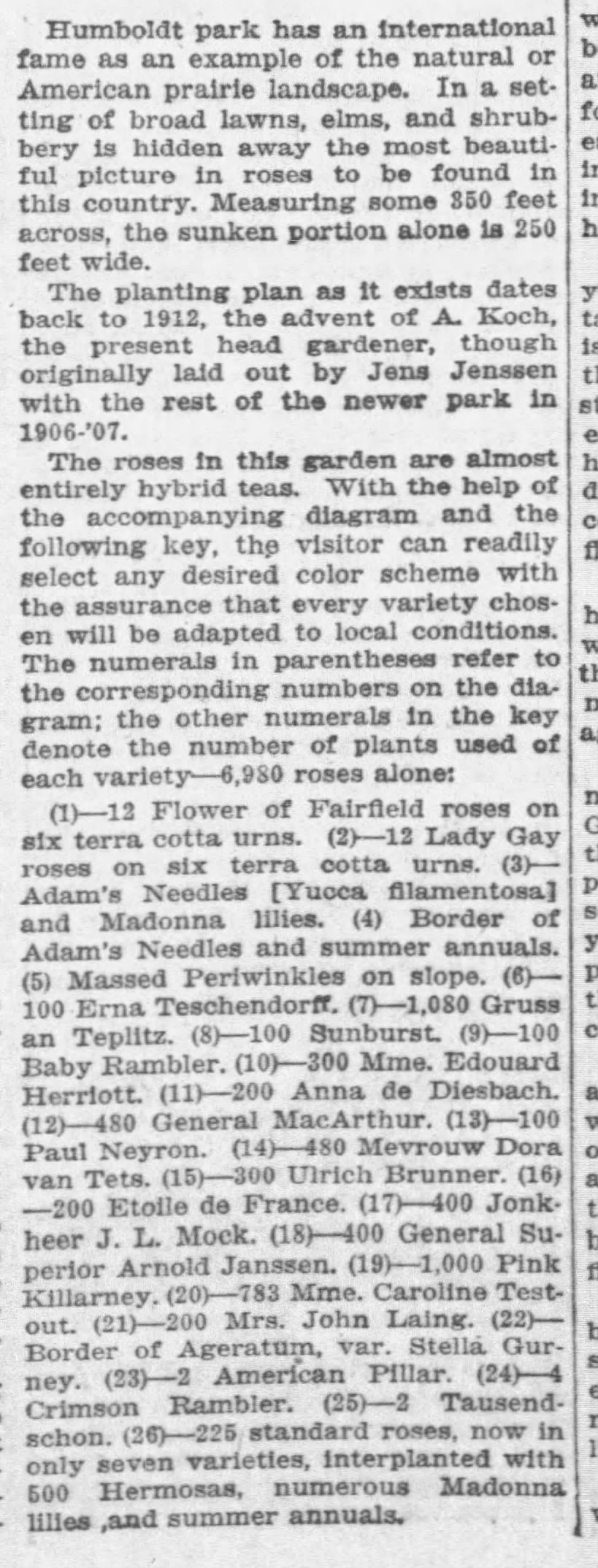

Not only a showcase for flowers, the Sunken Garden quickly became a public sculpture hotspot as well. Leonard Crunelle created the four bronzes cornering the water court. Commissioned specifically for Humboldt Park, “Maiden,” “Dove Girl,” “Crane Girl,” and “Fisher Boy" were installed in 1909. Crunelle's story is pretty compelling–born in France, he lived in Decatur as a teen, working as a coal miner, before he was hired to work in Lorado Taft's studio. Crunelle also did the Victory Monument on Martin Luther King Dr. in Bronzeville and the Heald Square Monument on Wacker. Blaming vandalism, the Parks Department removed the four bronzes here around 1951. They sat in storage for more than a decade, until they were reinstalled in Grant Park in 1964.

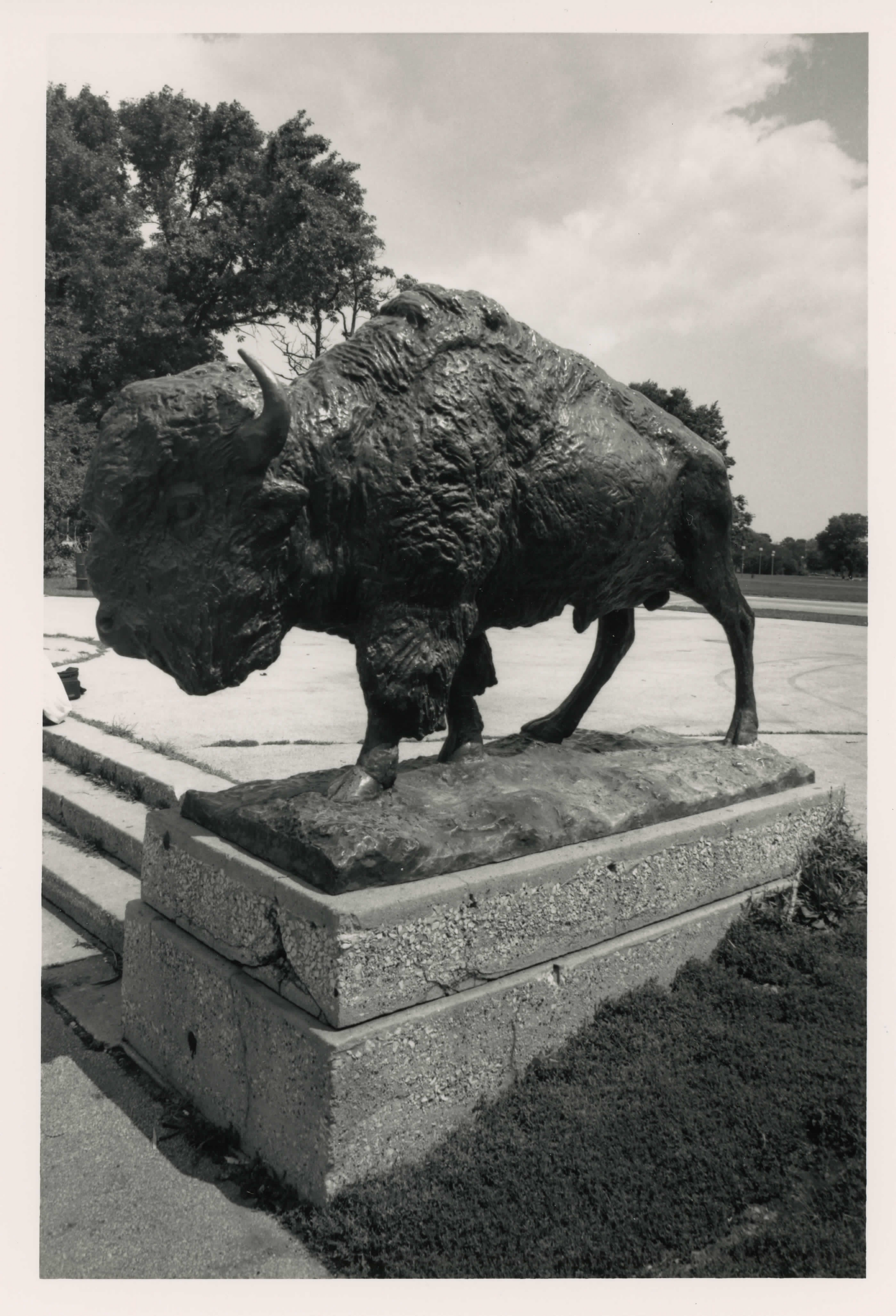

The sculptural survivors here are the bison, sculpted by Edward Kemeys. Kemeys and his wife, Laura Swing Kemeys, were the United States' preeminent animaliers (...there’s apparently a specific term for a sculptor of animals). Initially cast in plaster for the 1893 World’s Fair, a smaller version of the bison were recast in bronze for a sculpture exhibition in Garfield Park in 1909 before ending up here sometime in the 1910s. Kemeys also sculpted the Art Institute lions.

However, Kemeys' bison weren't the first animals to stand sentinel at the Sunken Garden. As part of a sculpture exhibition in the garden in 1908, plaster casts of Bulls with Maidens by Daniel Chester French and Edward C. Potter stood here. They were eventually cast in bronze, swapped with the bison, and installed in Garfield Park.

The large green Teco urns have disappeared. Produced by the American Terracotta Tile and Ceramic Company in Terra Cotta, IL (unincorporated McHenry County near Crystal Lake), they were once all over Humboldt Park, but it appears just about every single one has since been removed. The concrete drinking fountain basin is still there, as are the Schmidt, Garden, & Martin-designed lanterns, which also date to Jen Jensen's redesign of the park.

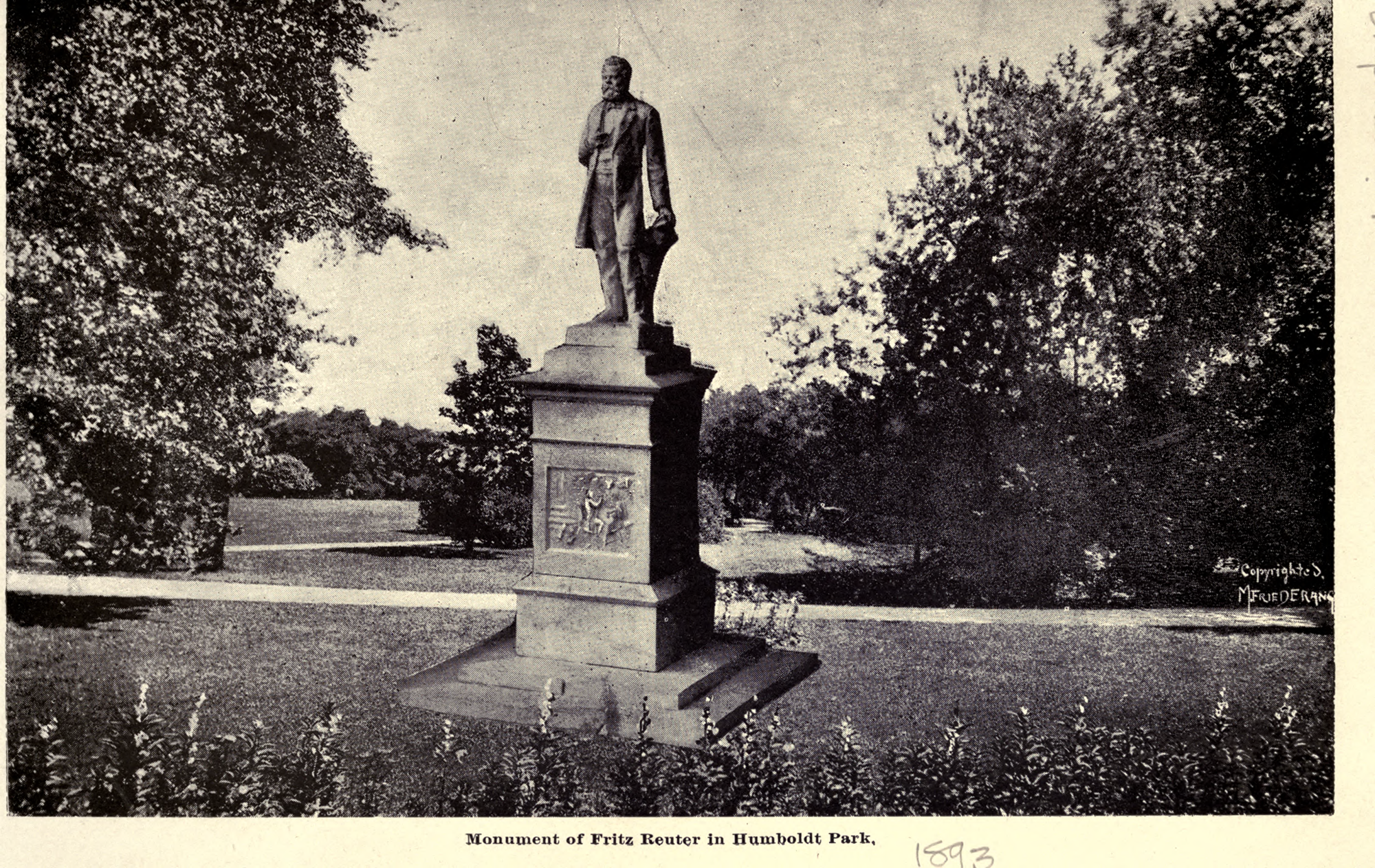

The statue in the background is the oldest part of this scene–the Fritz Reuter Monument was installed in 1893, the work of sculptor Franz Engelsmann. Donated by Chicago's German community, Reuter was a northern German novelist, "the Charles Dickens of the 'Plattdeutsche' people”. The Fritz Reuter Monument Association held a competition in 1887 to choose an artist to design the monument, which sculptor Aloys Loeher won. Something happened in the intervening few years, though, and by 1892, Engelsmann–who had not even entered the original competition–was presenting his models to the monument association and soaking up the credit at the dedication in 1893.

After decades of disinvestment by the financial system and neglect by local government, over last fews years capital has perceived a business opportunity in Humboldt Park's "good bones". Suddenly attention and investment returned to the park, and the forlorn Sunken Garden was an obvious candidate for revitalization. In the 2010s, the Chicago Parks Foundation developed a plan to restore the garden. They made it as far as selecting a designer for the project, Dutch garden designer Piet Oudolf, who launched his US career with the Lurie Garden in Millennium Park and also designed the gardens for New York's High Line. Given Oudolf's focus on native plants and perennials, it was an appropriate choice to build on Jensen's legacy. However, the project stalled for lack of funding and appears to have died–but given the amount of money sloshing around the east side of Humboldt Park, it's only a matter of time until something happens here.

Production Files

Further reading:

- The National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1992

- Great Julia Bachrach blog post on Jens Jensen and Humboldt Park

- "Chicago Parks and their Landscape Architecture" in Architectural Record in 1908

- "The Prairie Spirit in Landscape Gardening"

- 1907 write-up in Gardening about the Humboldt Park formal garden

Member discussion: