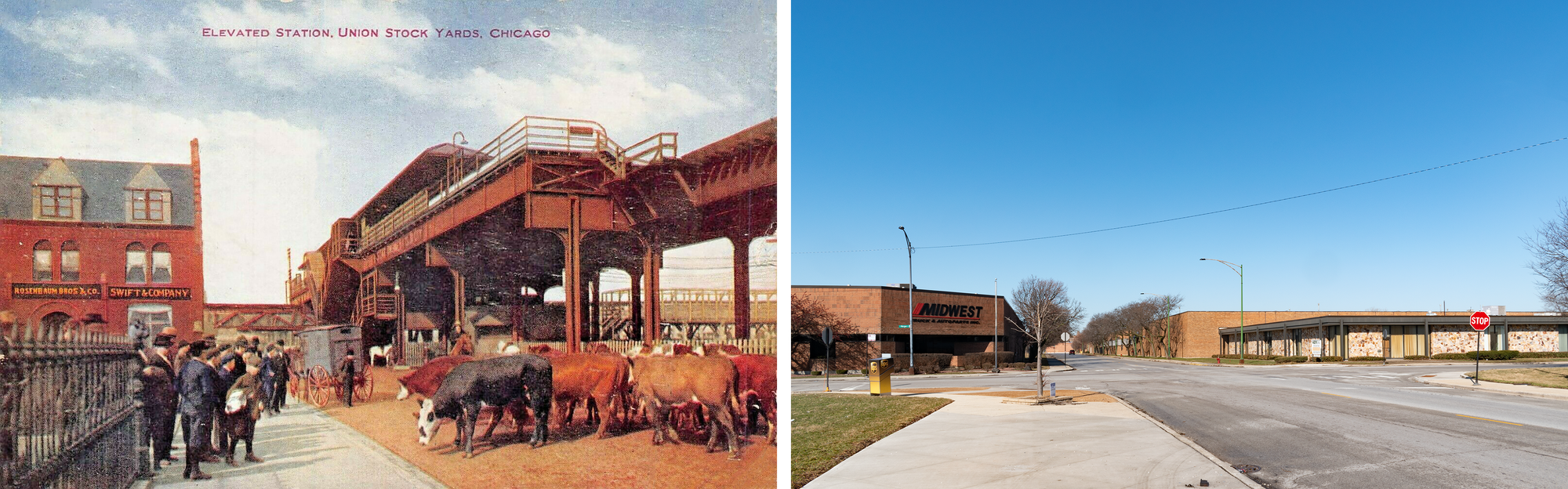

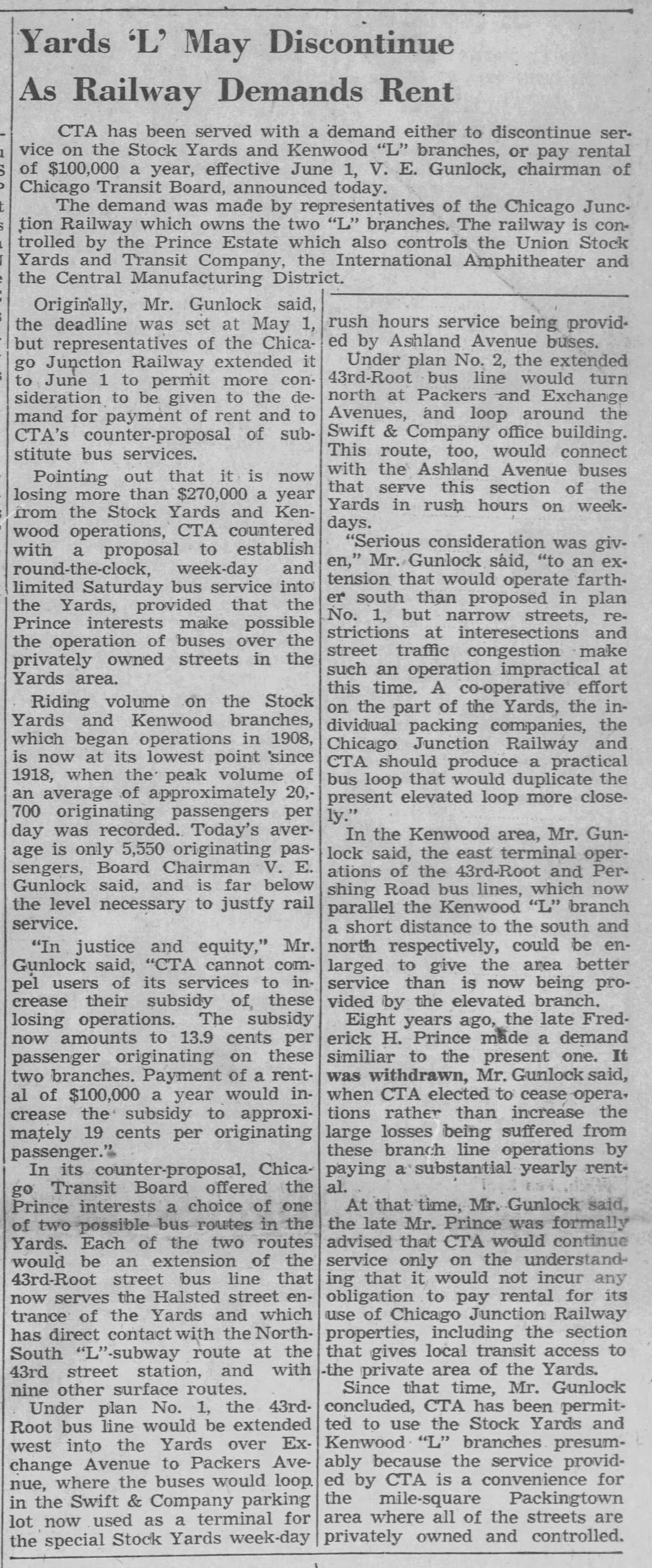

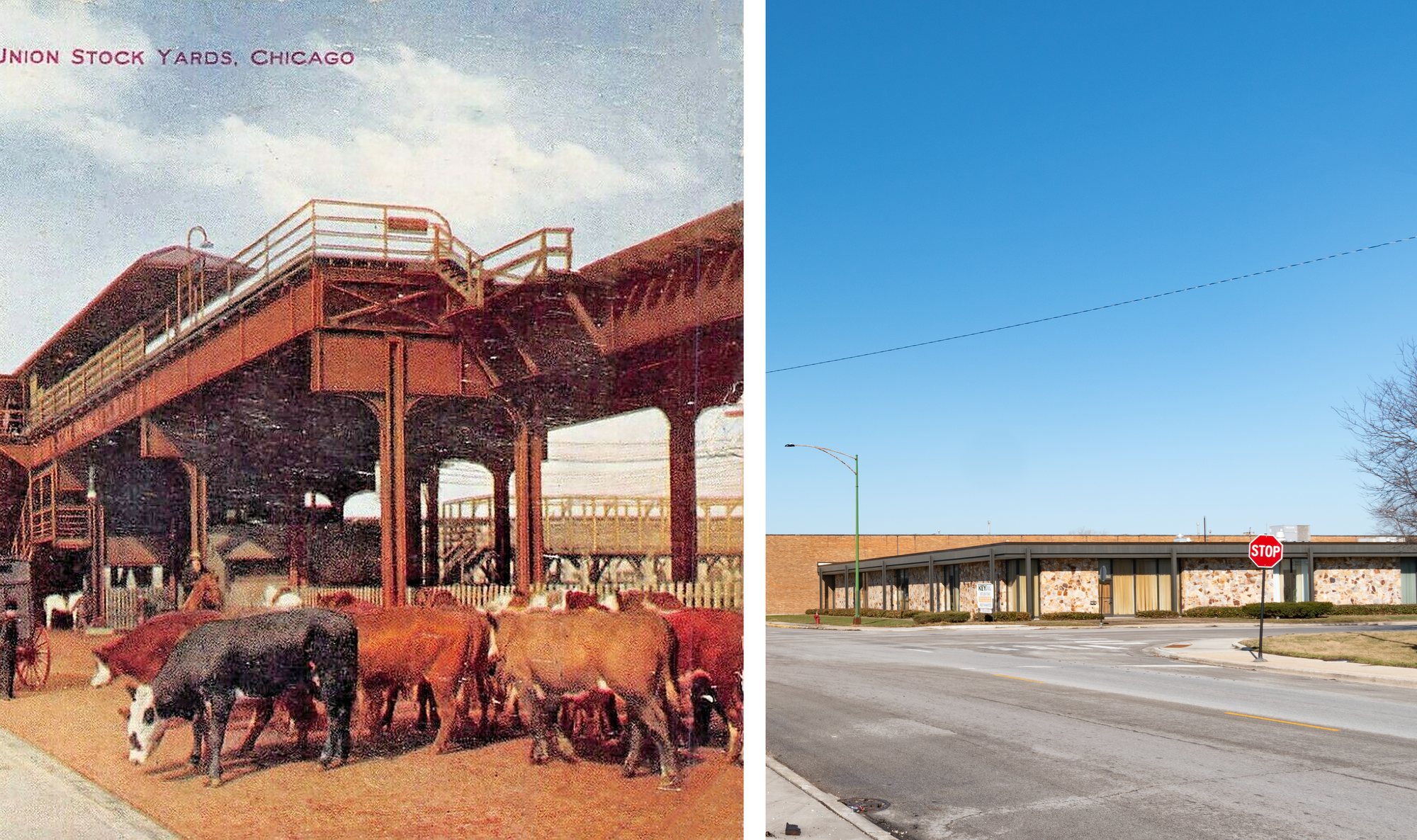

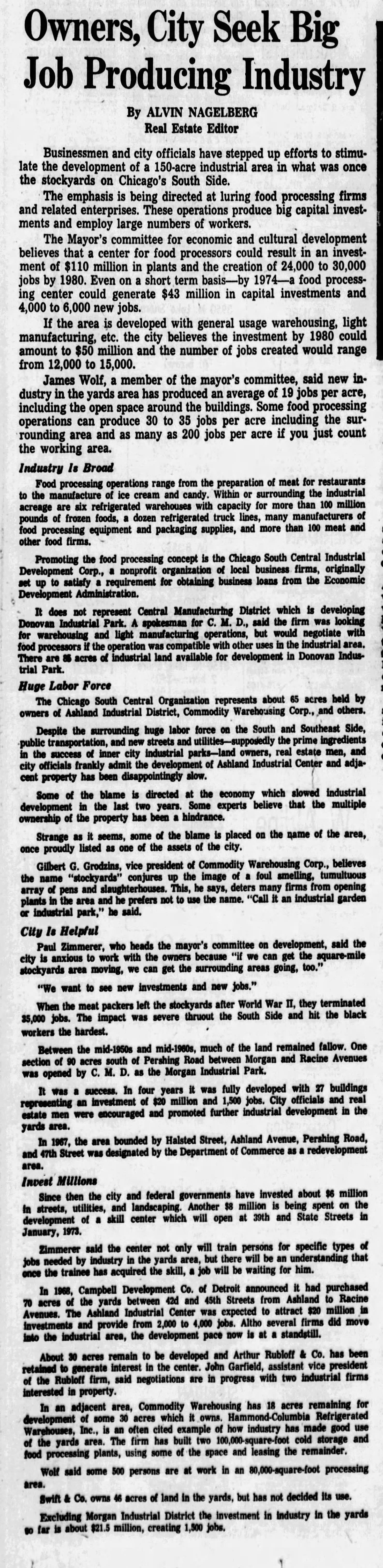

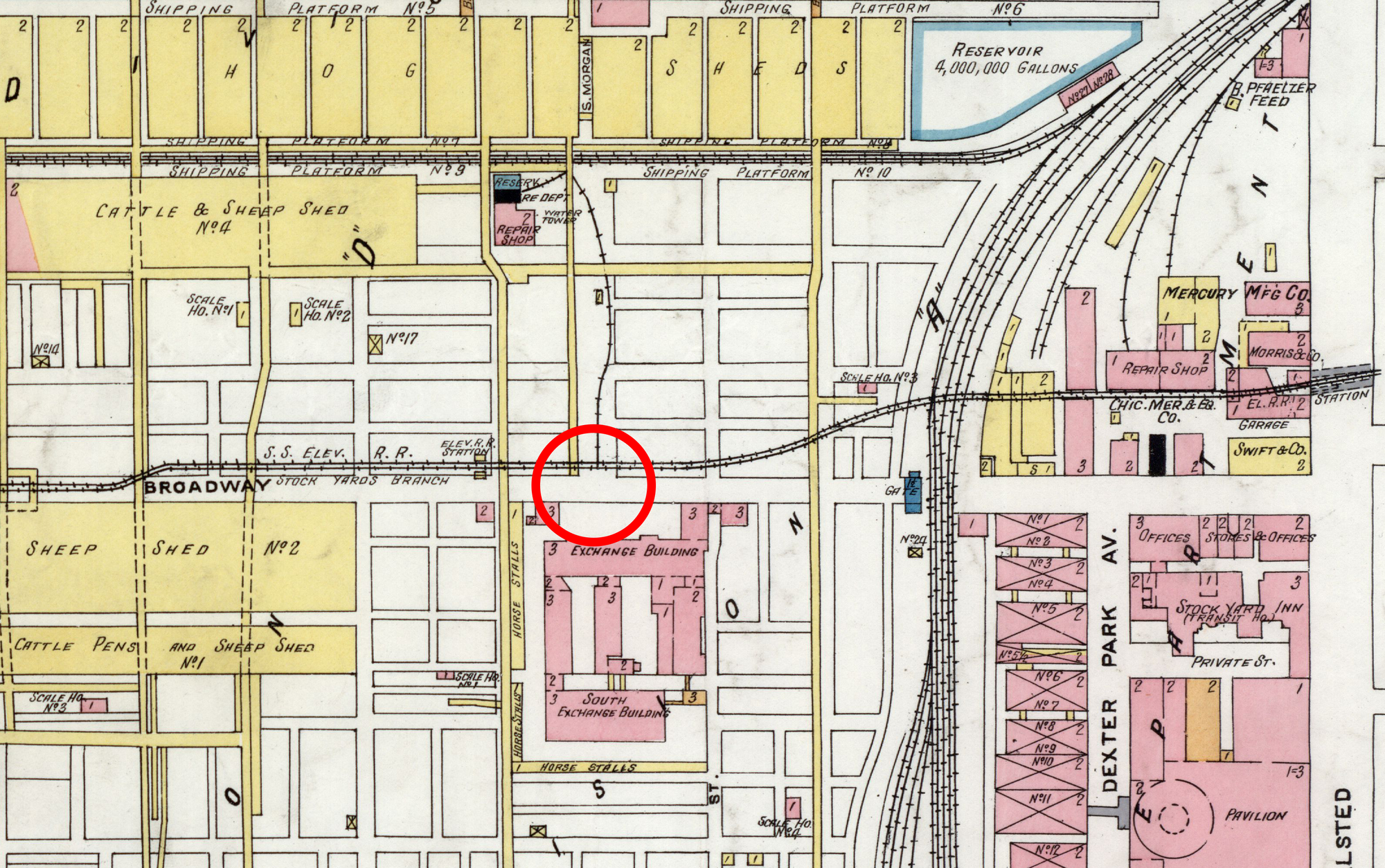

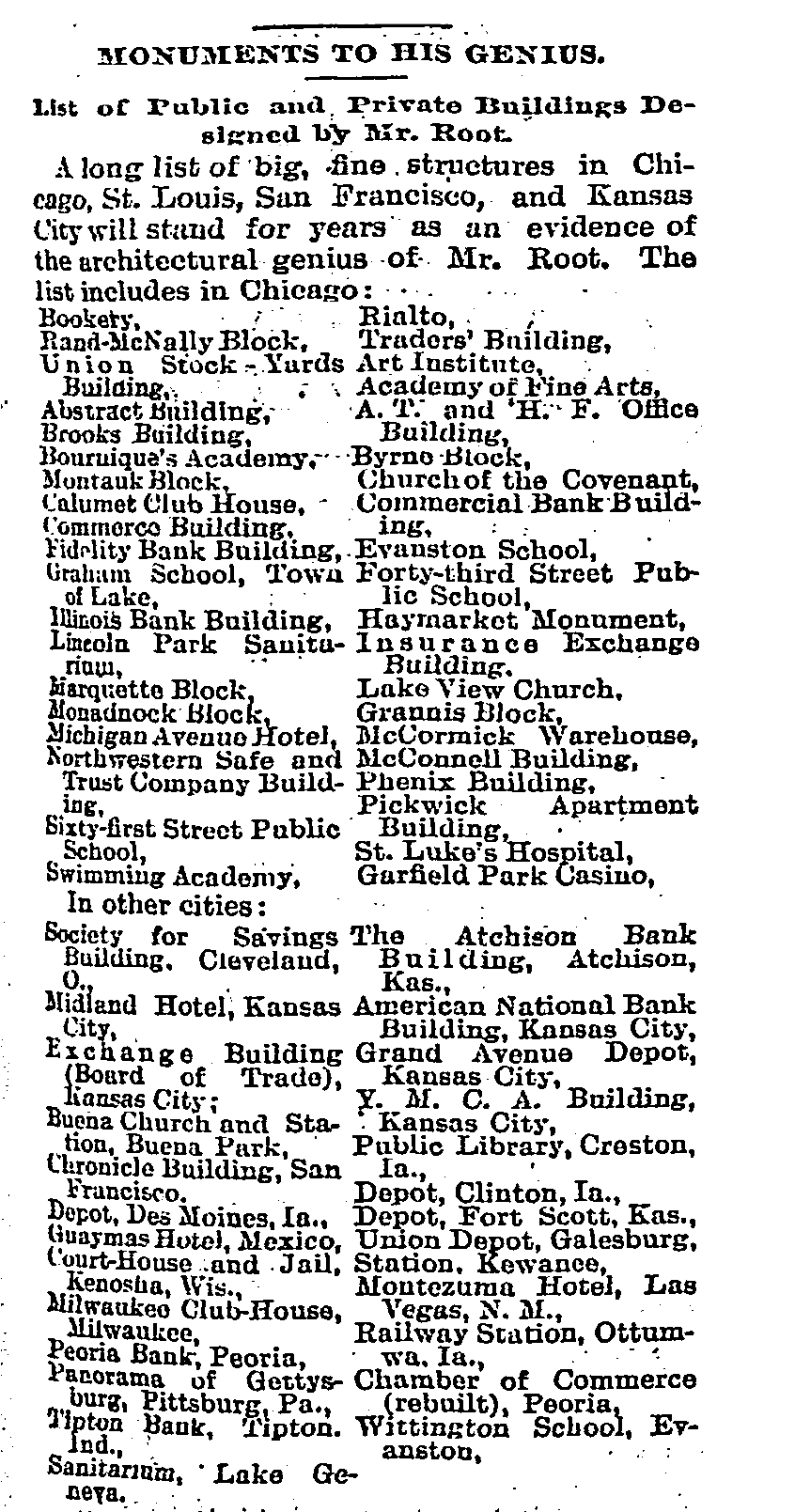

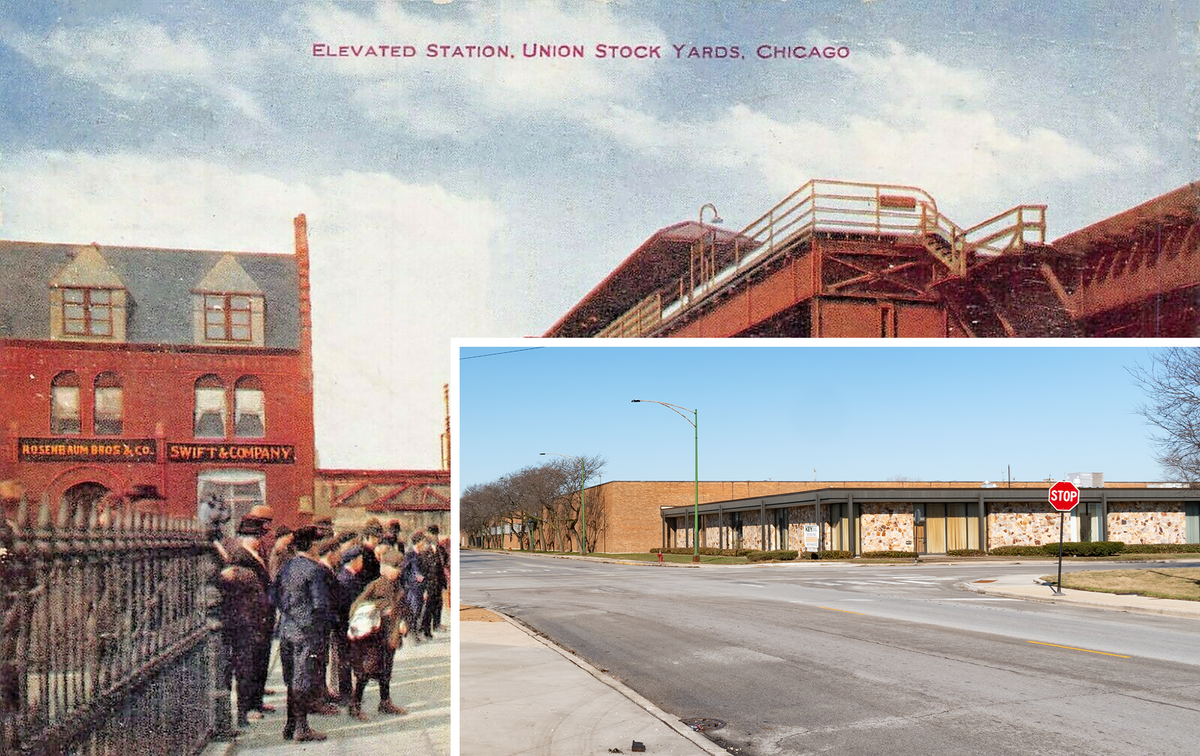

I don’t usually do these—where there’s nothing left of the postcard scene—but it took me so damn long to figure this one out that I’m writing about it anyway. I give you: the old Exchange Building at Chicago’s Union Stockyards and the Exchange Station on the Stockyards Branch of the L. Once the brains (the Exchange) and the veins (the L) of the world’s brawniest slaughterhouse district, it's now a random intersection in an industrial park (which is okay [well, mostly—that L would be nice to have]! the stockyards were hellish for people and animals alike and the model was obsolete).

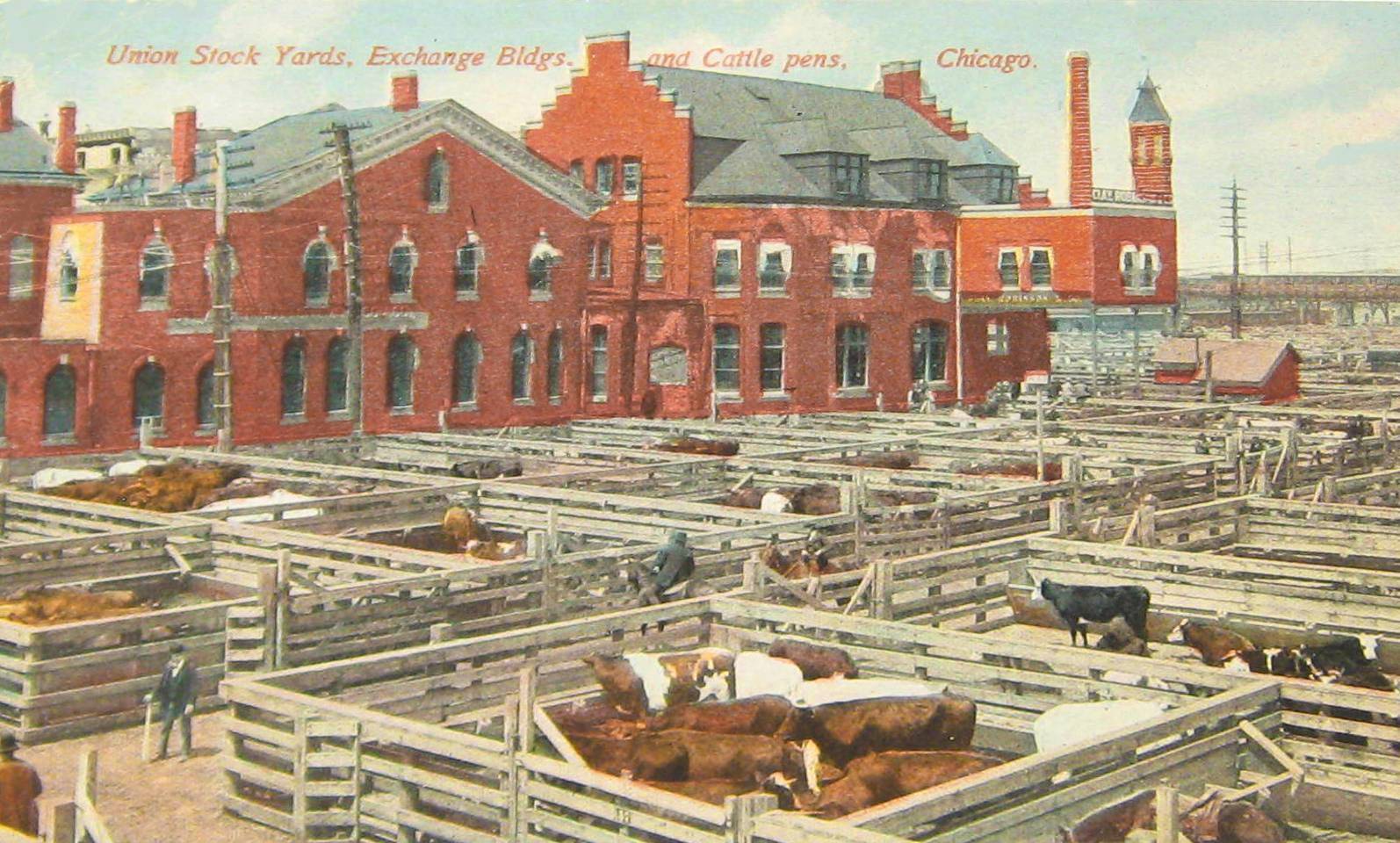

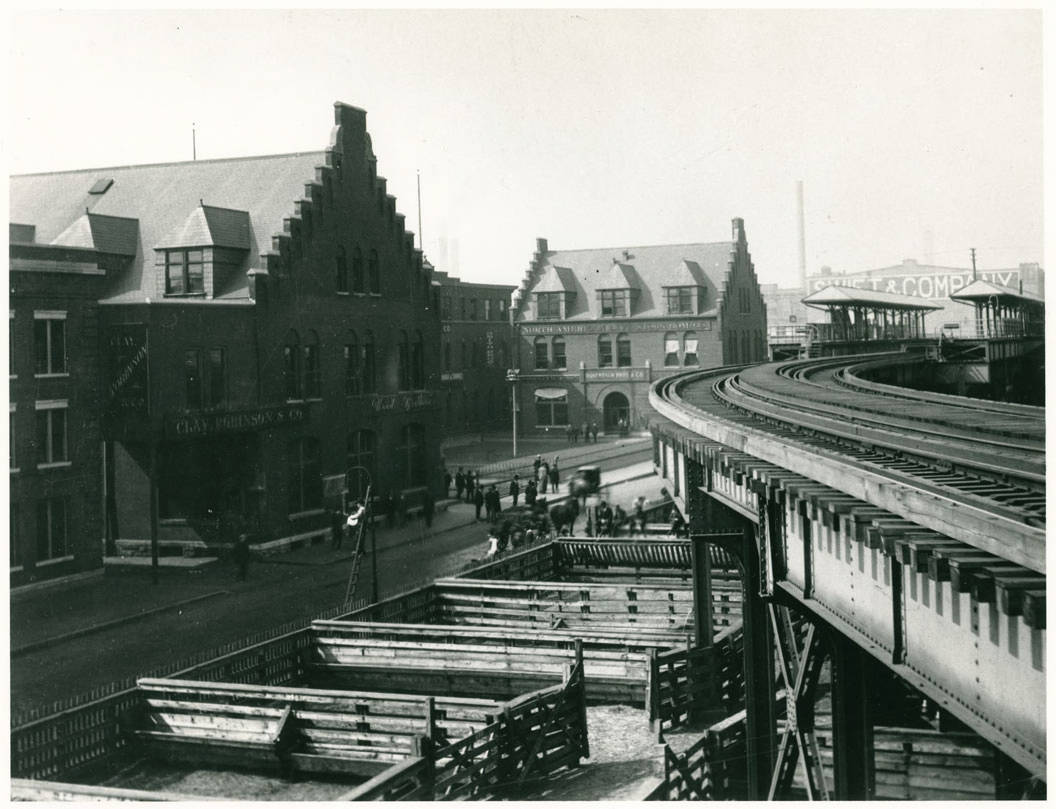

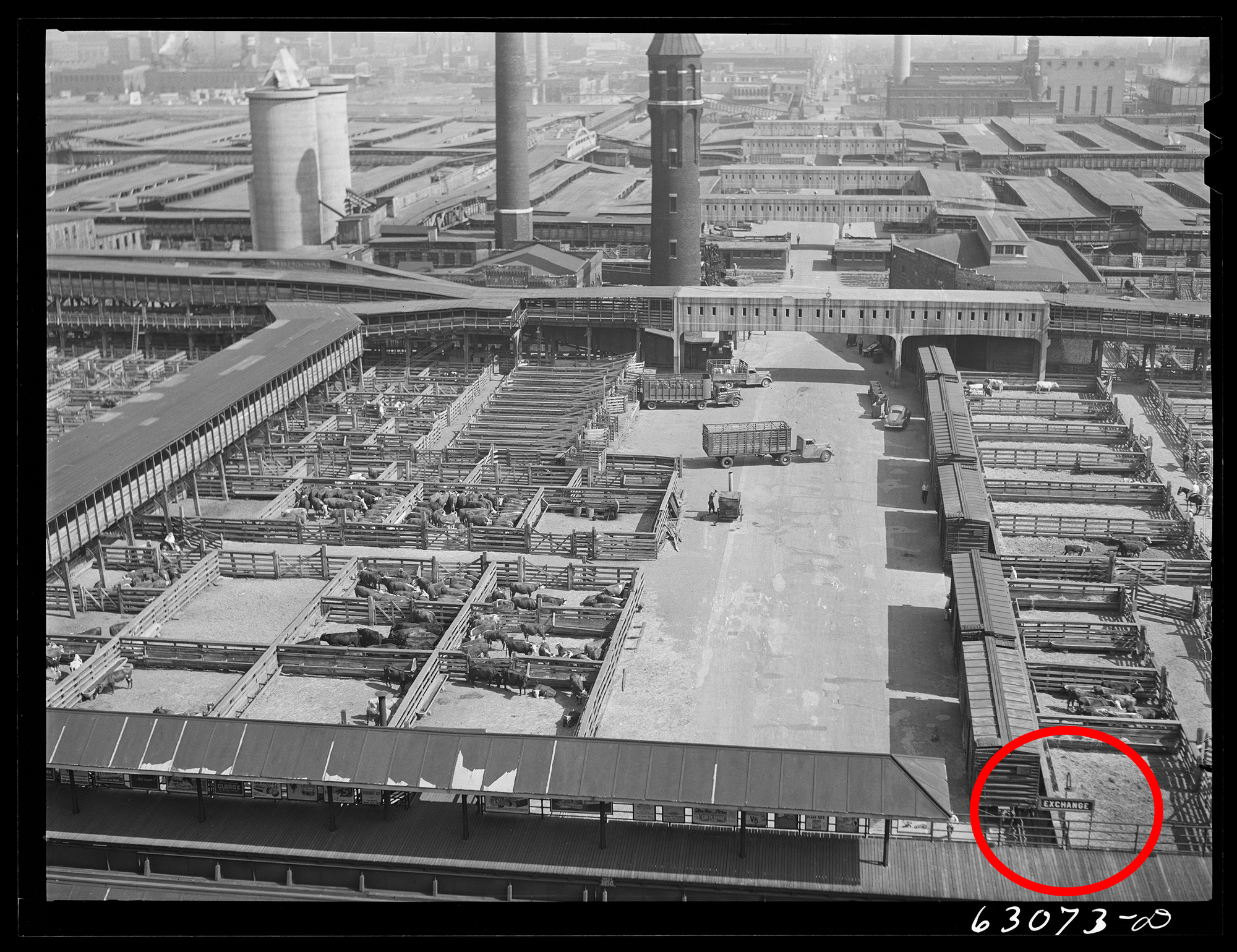

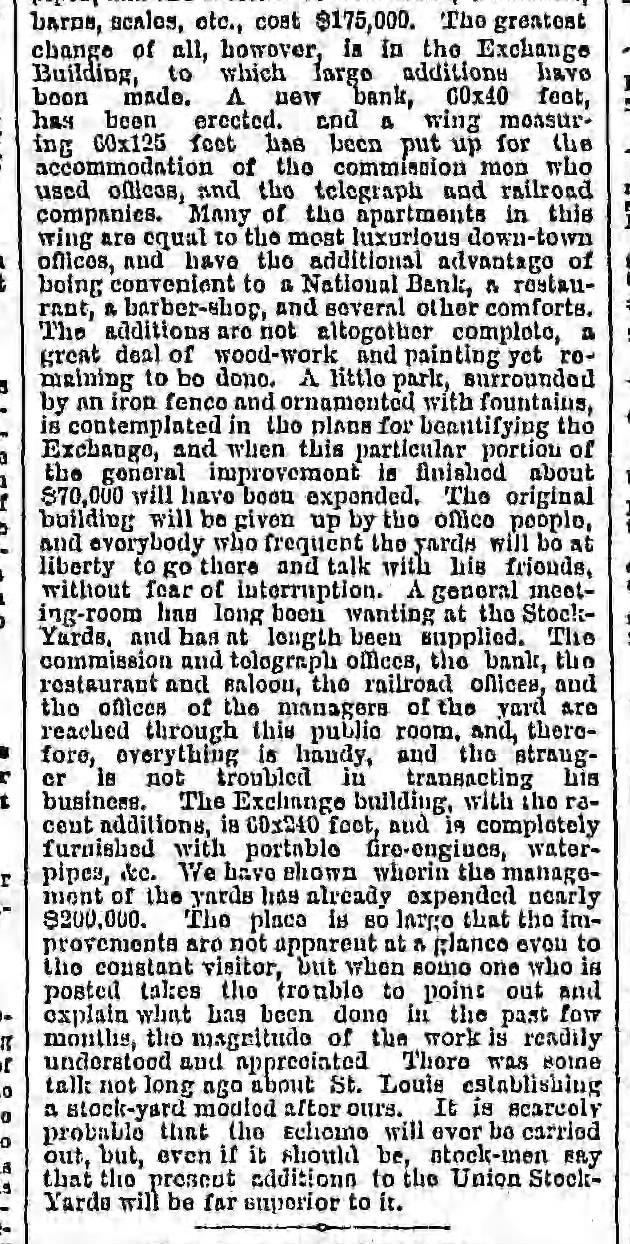

The “Swift & Company” sign visible on the Exchange Building is part of the reason it took forever to accurately locate this, because there was also a Swift station on the Stockyards Branch of the L (this postcard is often mislabeled or misused). …but no, this is the Exchange Building, home to the commission firms, the middlemen who represented cattle ranchers and sold their animals to the meat packers who slaughtered them here.

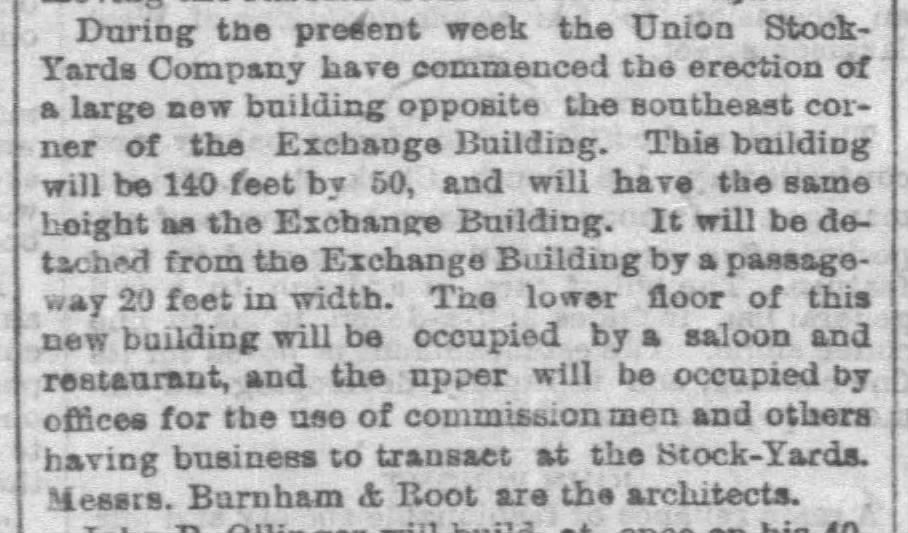

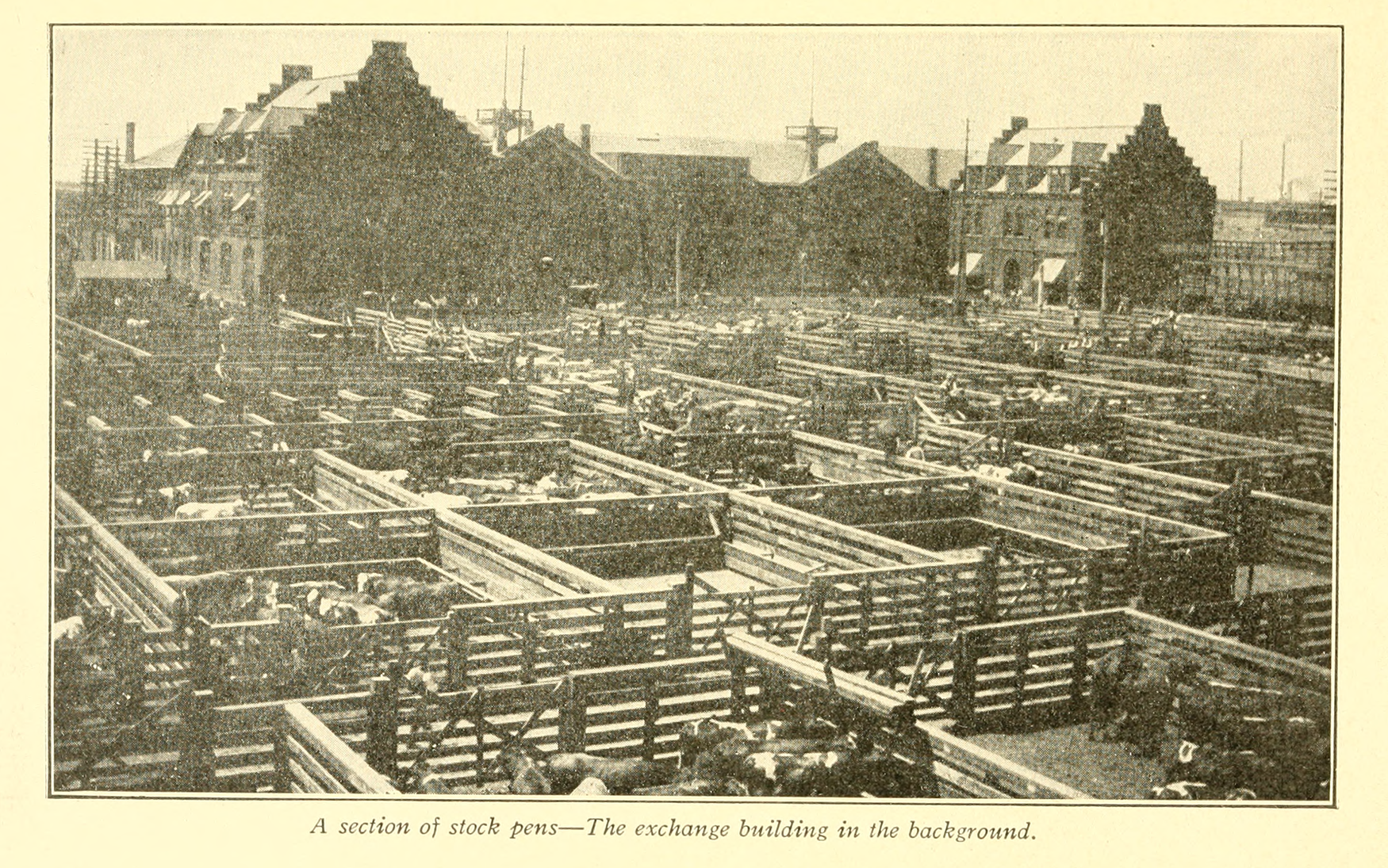

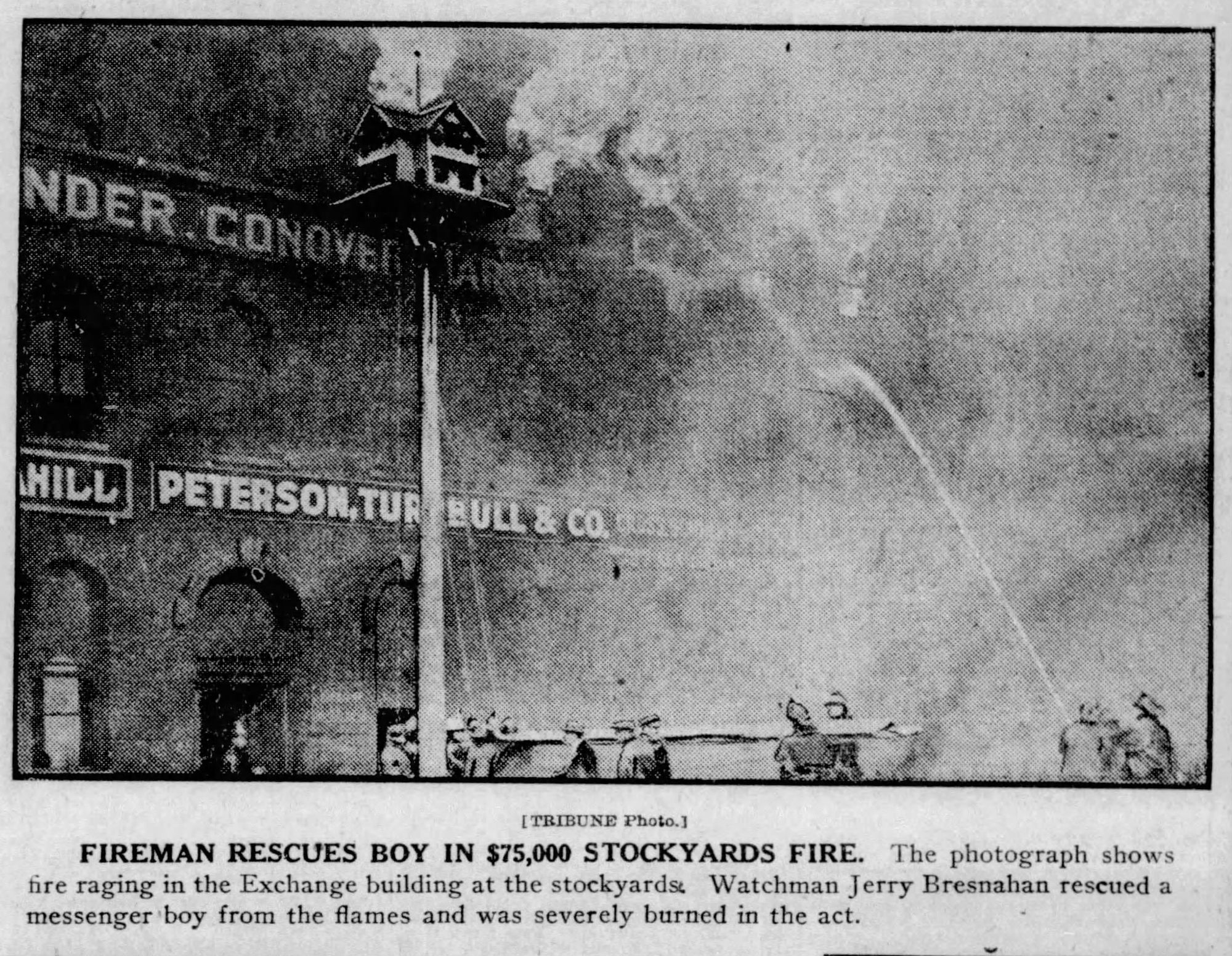

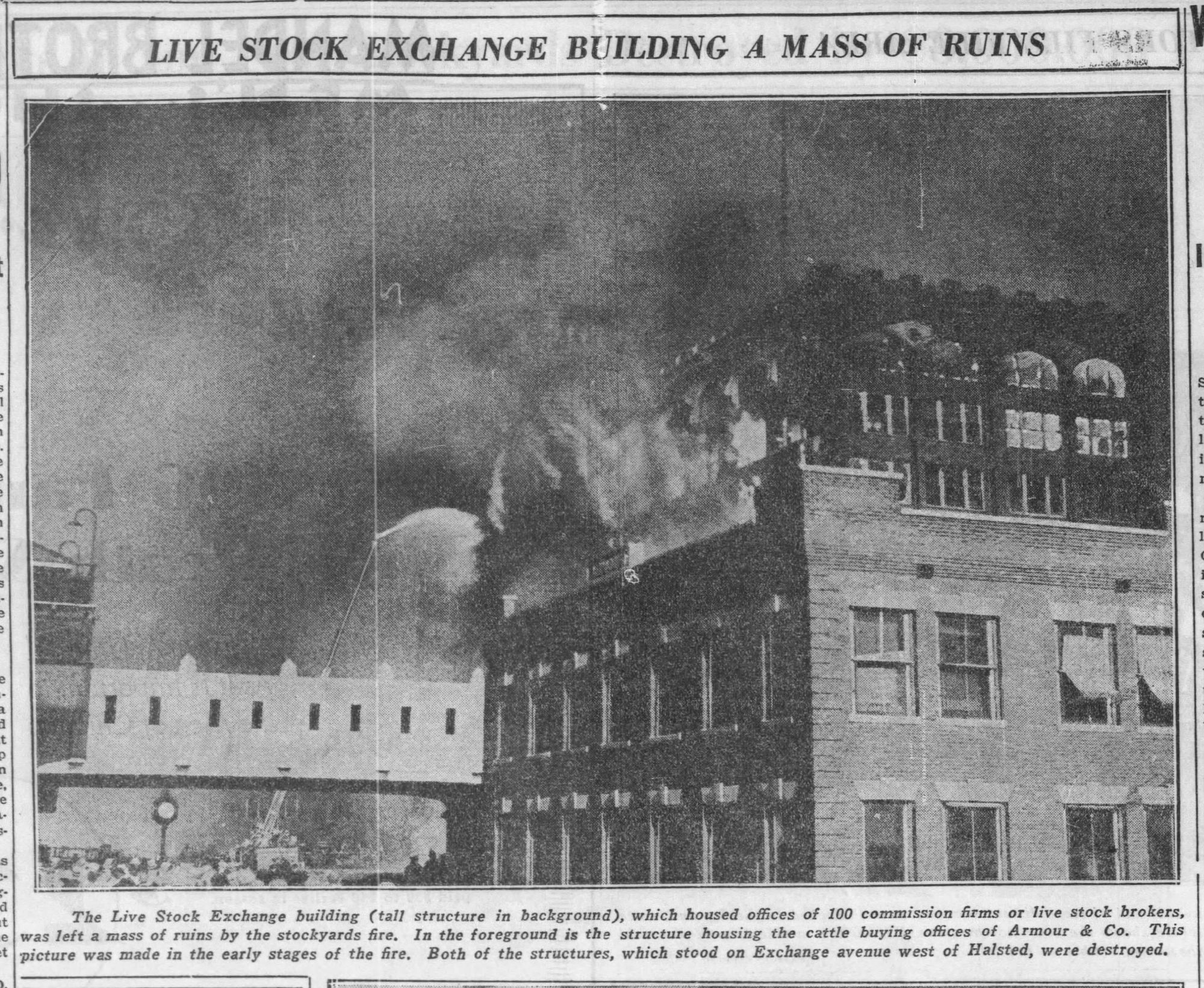

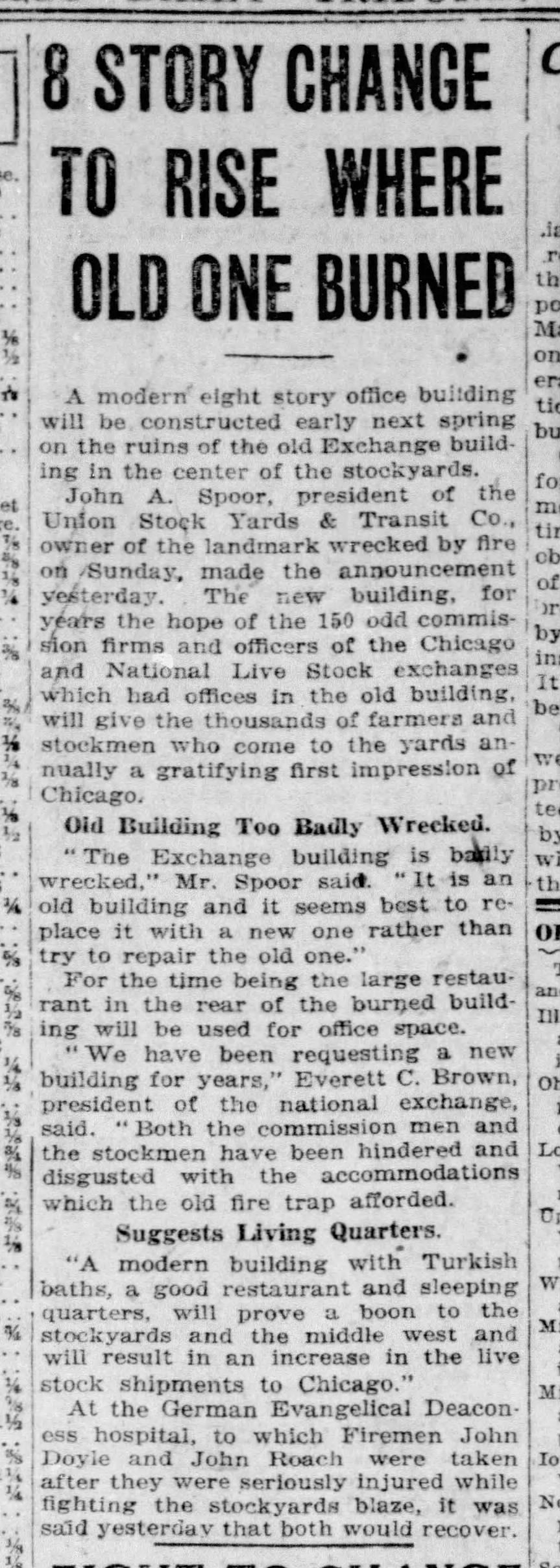

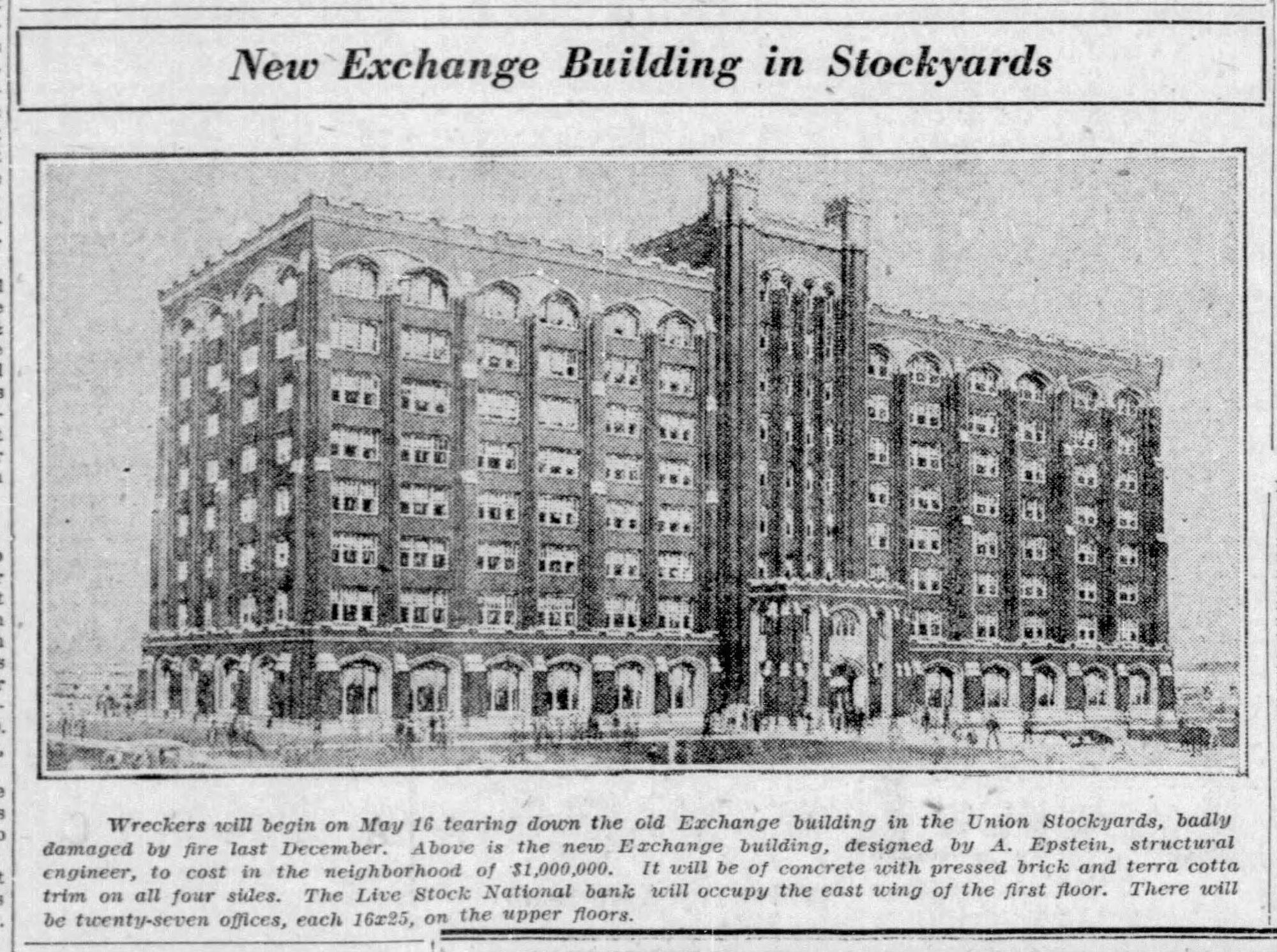

Built up in stages over the 1870s, at least parts of this version of the Exchange Building were designed by Burnham & Root. Home to 200+ commission firms, a telegraph office, a telephone exchange, etc., it was cramped and outdated by the 1910s. When a fire damaged the building in 1922, the Union Stockyards chose finish the job and tore it down. The replacement Exchange Building, completed in 1924, burned down only ten years later—fires bedeviled the Stockyards.

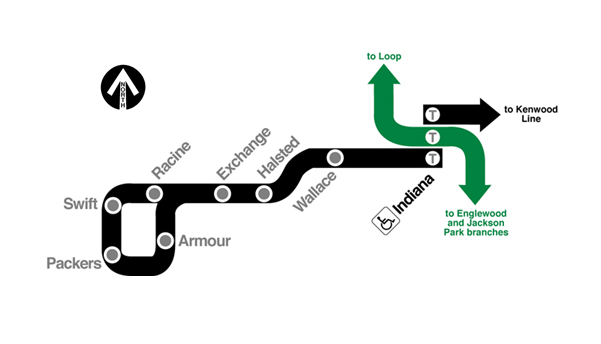

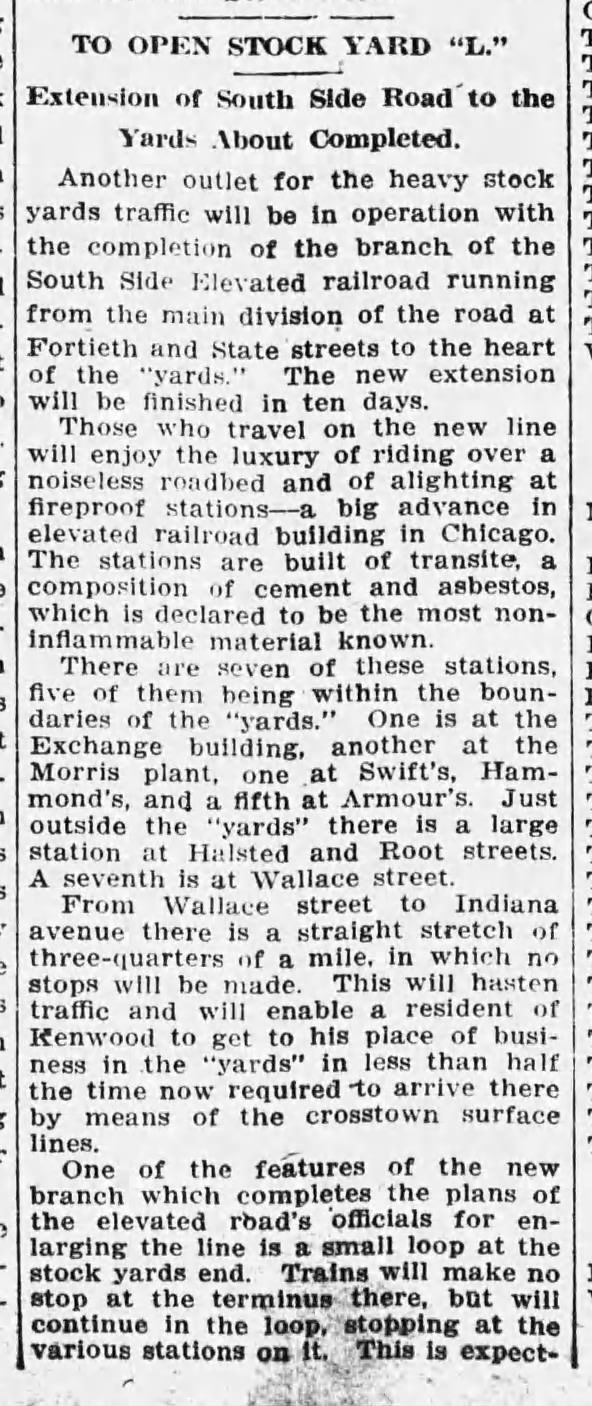

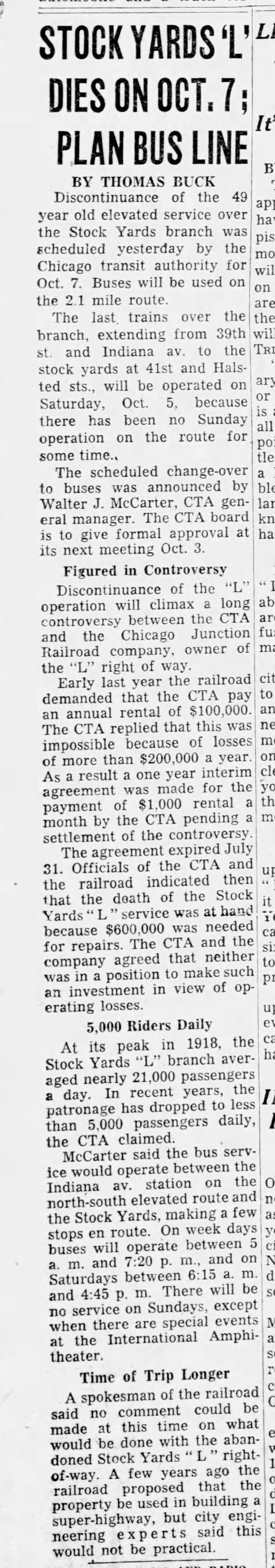

The Stockyards L, Chicago’s second Loop (maybe even more of a Loop than the original one, in that it circled the yards in only one direction), opened in 1908. Built to bring workers to the Stockyards, the branch operated mostly as a shuttle service that connected to the present-day Green Line at the Indiana station. It was a unique branch of the L—the tracks ran not over alleys or streets, but a maze of livestock pens, and most of the stops were named for the meatpacking companies (Swift, Morris, Armour) whose plants it served rather than any streets.

Rail and refrigerated train cars enabled the Stockyards to flourish, and it grew into the hub of an intricate system linking ranchers in the West, feedlots in Iowa, and consumers of dressed beef across the country, all connected by railways–with Chicago's South Side always at the heart. By the 1930s, though, trucking and improved refrigeration began to chip away at the Stockyards model–there's less need for an expensive middleman between ranchers and packers when refrigerated trucks mean you can slaughter your animals closer to where they're reared (plus, the land's cheaper and there are fewer witnesses to the barbarity of the industrial meat system too [harder to write the Jungle]). World War II briefly arrested the decline, but by the late 1940s it was clear that the Stockyards were dying.

In the midst of that decline, the CTA took over the Stockyards branch in 1947. Passenger numbers cratered as the Stockyards emptied out in the 1950s. Obsolete rolling stock deepened the sense of neglect and decay —this branch used some of the oldest, ricketiest trains in the CTA fleet. The Stockyards branch closed in October 1957, and the CTA demolished the Exchange Station soon after.

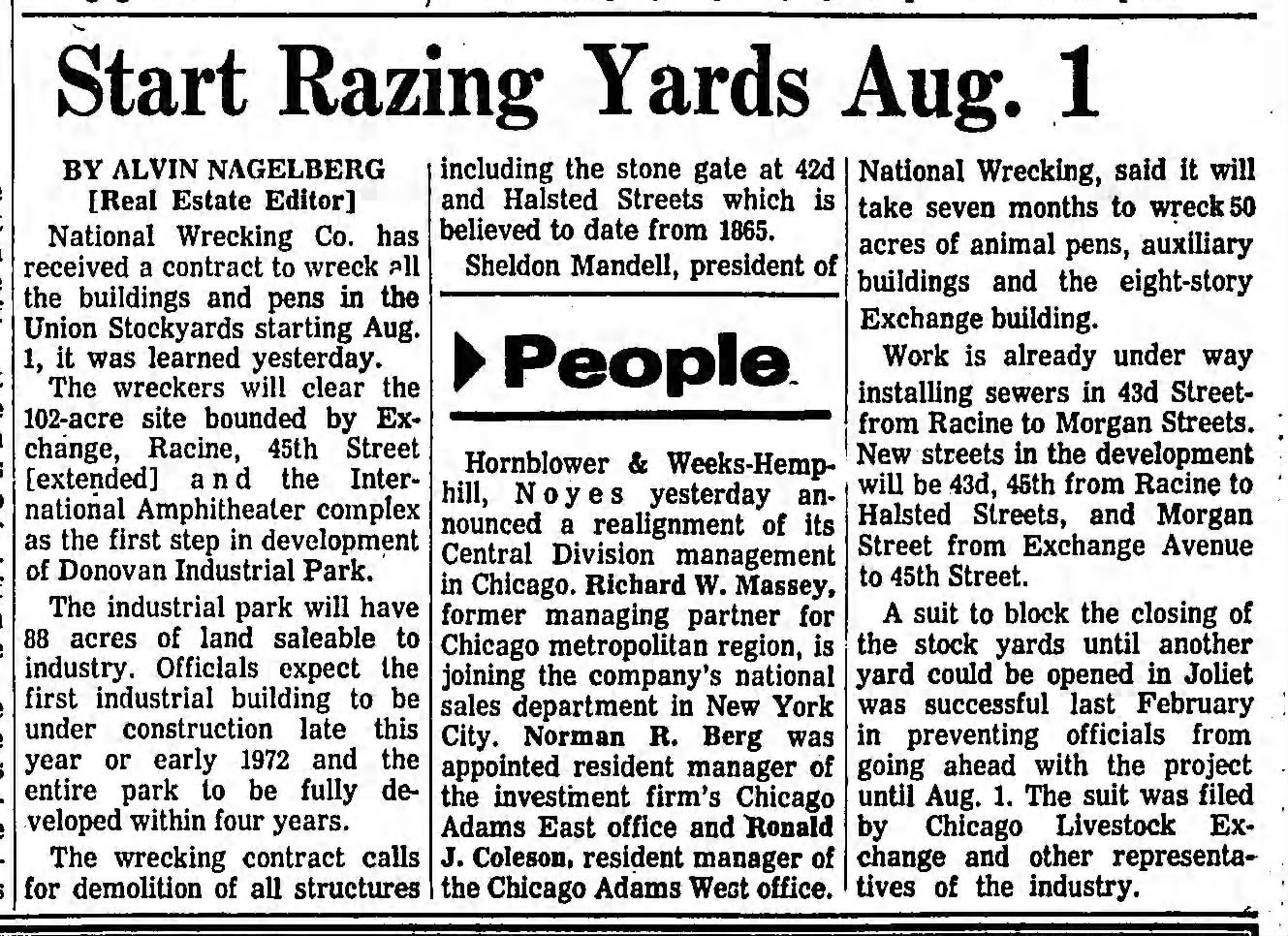

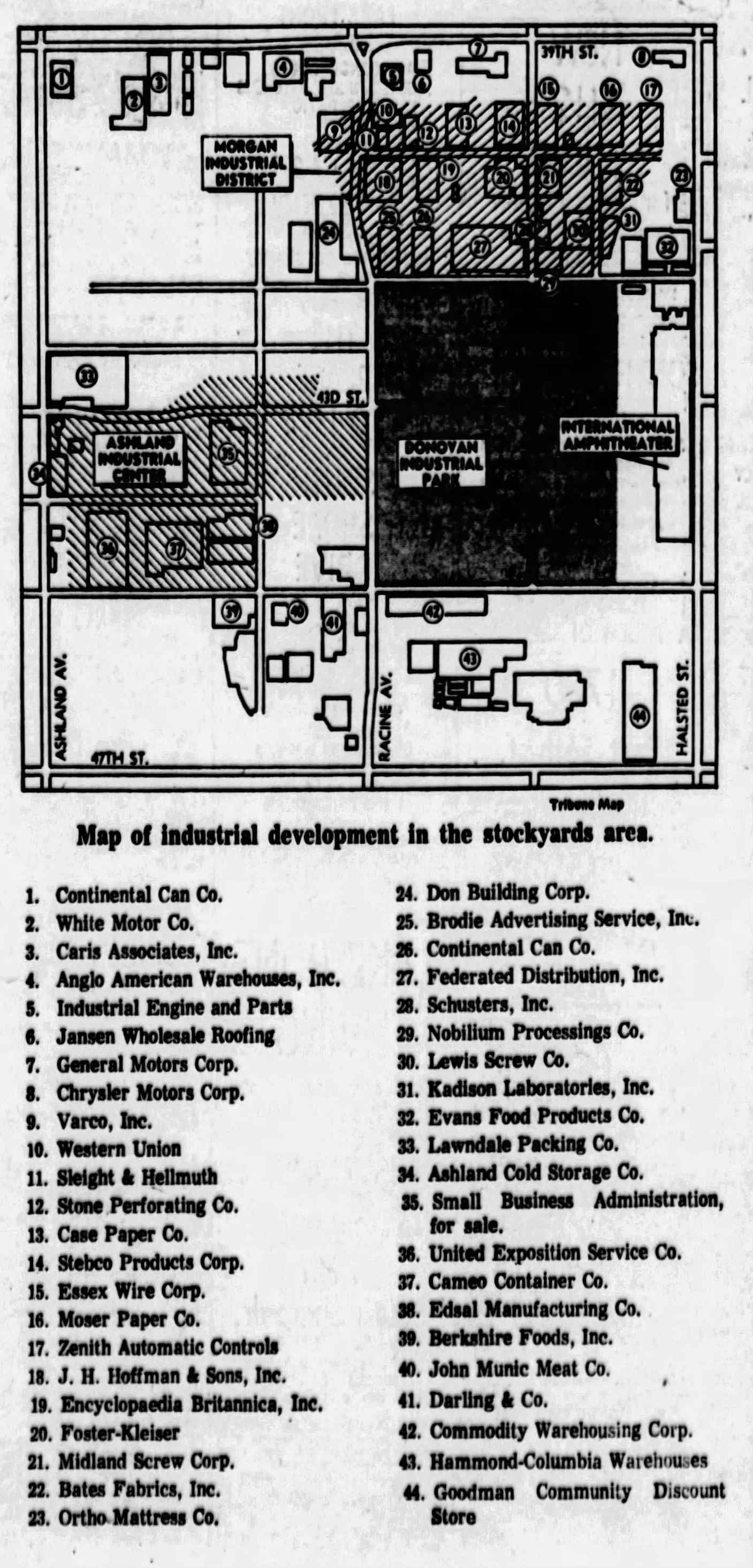

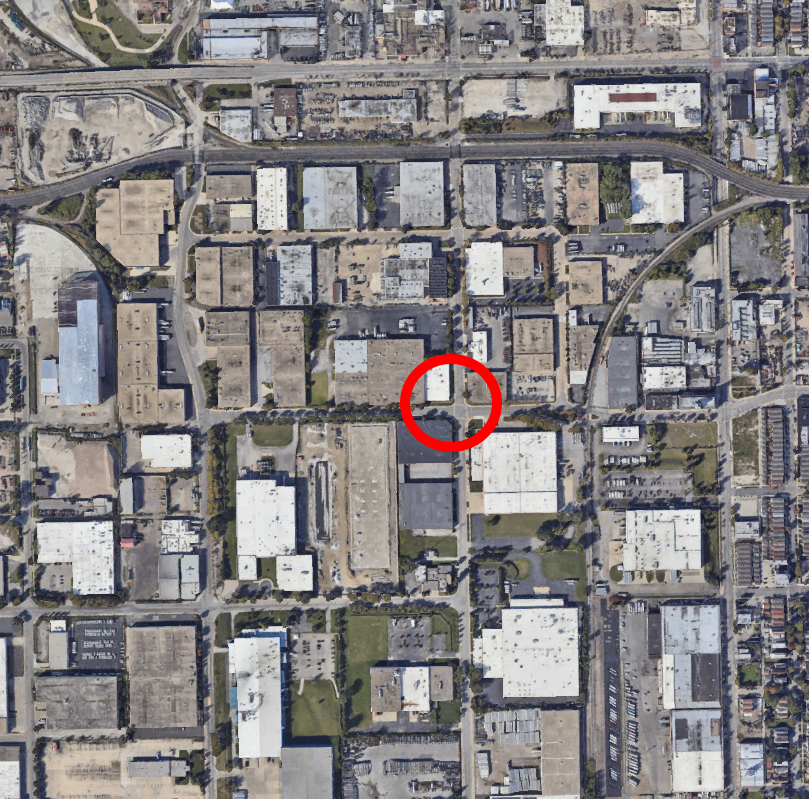

With their core business withering away, the Union Stockyards Company turned to industrial real estate development, aided by strong financial support from the city, state, and federal governments, who were worried about losing an entire neighborhood's worth of jobs. The section north of Exchange Ave.—the right side of the postcard—was cleared of livestock pens in the late 1950s or early 1960s. Dubbed the Morgan Industrial District and roughly bounded by Pershing, Exchange, Racine, and Halsted, this was the first part of the former Stockyards redeveloped into industrial uses (...I didn't realize they did this in chunks, although it's pretty obvious in retrospect). The mid-century modern office building was built in 1968, and over the years it has been home to liquor distributors, an auto parts manufacturer, and now a food distributor in KEY Food Services.

The area south of Exchange Ave.—the left side of the postcard—was redeveloped a bit later. The Exchange Building, whose replacement still stood on this site, was demolished once the Stockyards finally closed in 1971. Redeveloped in the 1970s as the Donovan Industrial Park (named for Union Stockyards chairman James F. Donovan), the building on the left was built in 1975 and has since housed a restaurant supply store and an auto parts distributor.

Public money and government support was crucial to the survival of the old Stockyards as a job center. Government was investing in the reinvention of the area even before the Stockyards closed—the Department of Commerce's Economic Development Administration provided $4.9m grant for redevelopment in 1968, the equivalent of $43.5m today.

This was also Chicago's first industrial TIF district. The state of Illinois enacted a law permitting Tax-Increment Financing districts in 1977, and the city created the Stockyards TIF in 1989 (this corner is actually just outside the TIF district, which starts on the east side of Racine). In a TIF district, revenue from property taxes paid directly to the city is essentially frozen for a determined time period. As the value of the property rises (and thus the property tax revenue), any excess tax revenue above that frozen baseline goes into a TIF fund that can only be spent on projects in the TIF district. So here: imagine that office building on the right had an assessed value of $1m in 1989 (totally hypothetical, pulling these numbers out of my ass). The property owner would continue to pay that same amount of taxes into the city's normal treasury for the life of the TIF district. However, say that over that time period the value of the property rose to $2m–the tax revenue paid by the landowner on that extra $1m would go into a dedicated fund that could only be spent in the TIF district, geographically ringfencing it to the immediate neighborhood (usually–some of these districts are drawn weird).

Way smarter people than I have written at length about TIFs, which are controversial in Chicago. There's a perception that there's a lack of accountability and public control over how TIF funds are spent, that the city is setting up TIF districts in areas where they're not needed (cough Lincoln Yards cough), and that TIFs divert tax revenue away from critical needs like public schools. TIF defenders would argue that that growth in tax revenue wouldn't happen without improvements paid for by the TIF, so without it there would be no increases in tax revenue to spend on public schools anyway [...there are a lot of TIF districts where I don't particularly buy that justification]). At their best, they can spur development that would otherwise not occur but for the TIF, or shape development in ways that benefit the public–they city using the LaSalle/Central TIF to spur the adaptive reuse of old office buildings in the Loop into affordable housing a recent exciting example.

The Stockyards Industrial TIF, which expired in 2012, was used to entice companies to stay and grow in the Stockyards Industrial Park. For example, in 2012, $2.2m of public funds from the TIF were given to a chemical manufacturer, Cedar Concepts, to help them assemble a site in the Stockyards and build a larger manufacturing plant (they're still there, so this appears to be a cautious success).

I guess you can chalk up the industrial redevelopment of the Stockyards as a qualified success—more than 10,000 people are employed in the industrial corridor. While the area didn't escape the wave of industrial job losses that swept the US over the last 50 years, perhaps it helped stanch the bleeding (without a counterfactual it's hard to say for certain) and keep jobs close to city residents. At the very least, it preserved the industrial amenities of the district and kept it ready for companies like Testa Produce and Nature's Fynd to move into the area. Now, with re-shoring, changes in supply chains, and demand for conveniently located light industrial, warehousing, and logistics space once again hot, the Stockyards are once again bustling–although it's mostly trucks, few trains, and it probably smells better.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Slaughterhouse: Chicago’s Union Stock Yard and the World It Made by Dominic Pacyga

- There was a bunch of press around Pacyga's book, including some interesting interviews

- Obviously, Nature's Metropolis by William Cronon

- There was recently a very good WTTW documentary on the Stockyards, "The Union Stockyards — A Chicago Stories Documentary"

- And an excellent companion article

- The always amazing Chicago-L.org on the Stockyards Branch

- Some interesting public domain histories of the Stockyards: an Illustrated History from 1901 and the History of the Yards, 1865-1953

- Fascinating footage and interviews from the day it closed in 1971

- The City of Chicago page on the Stockyards Industrial TIF District

- The TIF, and the regular old public money that flowed into saving the Stockyards as a major employment district before the TIF, has been regularly pointed to as an example of successful public intervention, a positive use of TIFs, etc. In the American Prospect, in the Baltimore Sun, in random-ass journals (PDF), and pointed to by other municipalities.

- The industrial building that stands on where the Exchange Building once stood was recently for lease, if you're looking

- The other one, the office building on the north side of Exchange Ave., was bought for redevelopment in 2022

- City document from 2017-2018 on employment in the Stockyards Industrial Corridor

Member discussion: