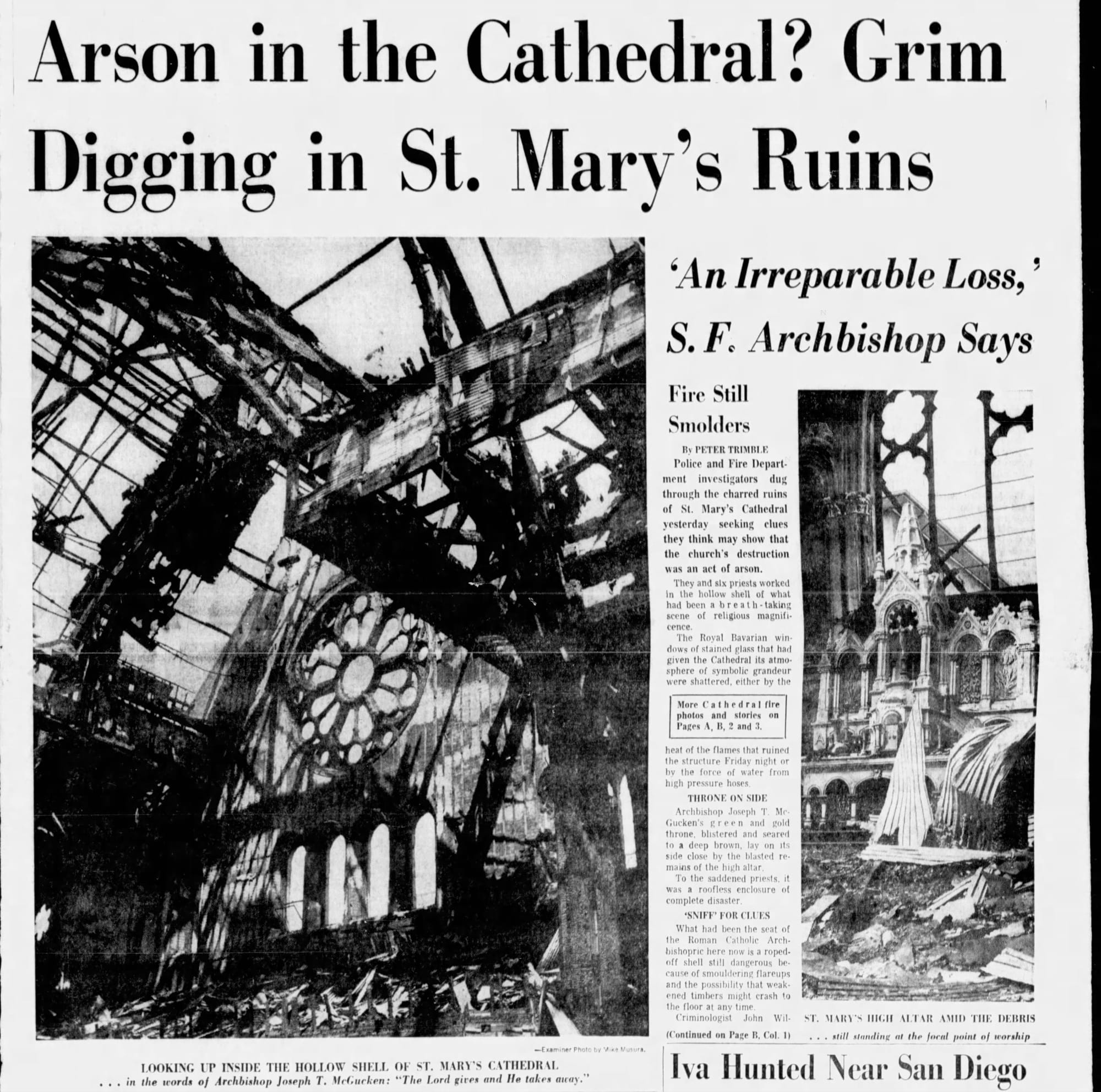

An icon of ecclesiastical modernism and structural expressionism, the story of San Francisco’s St. Mary’s touches on urban renewal, Vatican II, and maybe a hint of plagiarism. It also illuminates one of the more obscure reasons our cities grew so much shittier: when the second iteration of St. Mary’s Cathedral burned down in 1962, the archdiocese had to build the new one on a much larger site a few blocks away because of…parking minimums!

San Francisco’s 1960 zoning code required houses of worship to have one parking spot for every ten seats, and there was no room for a 240 car parking lot on the church’s former location at Van Ness & O’Farrell. Instead, the City of San Francisco, the Archdiocese, and real estate interests came together for a complicated deal that secured a plot of recently-cleared land controlled by the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency in Western Addition. Designed by Pier Luigi Nervi and Pietro Belluschi, together with John Michael Lee, Paul A. Ryan and Angus McSweeney, St. Mary of the Assumption was dedicated in 1971.

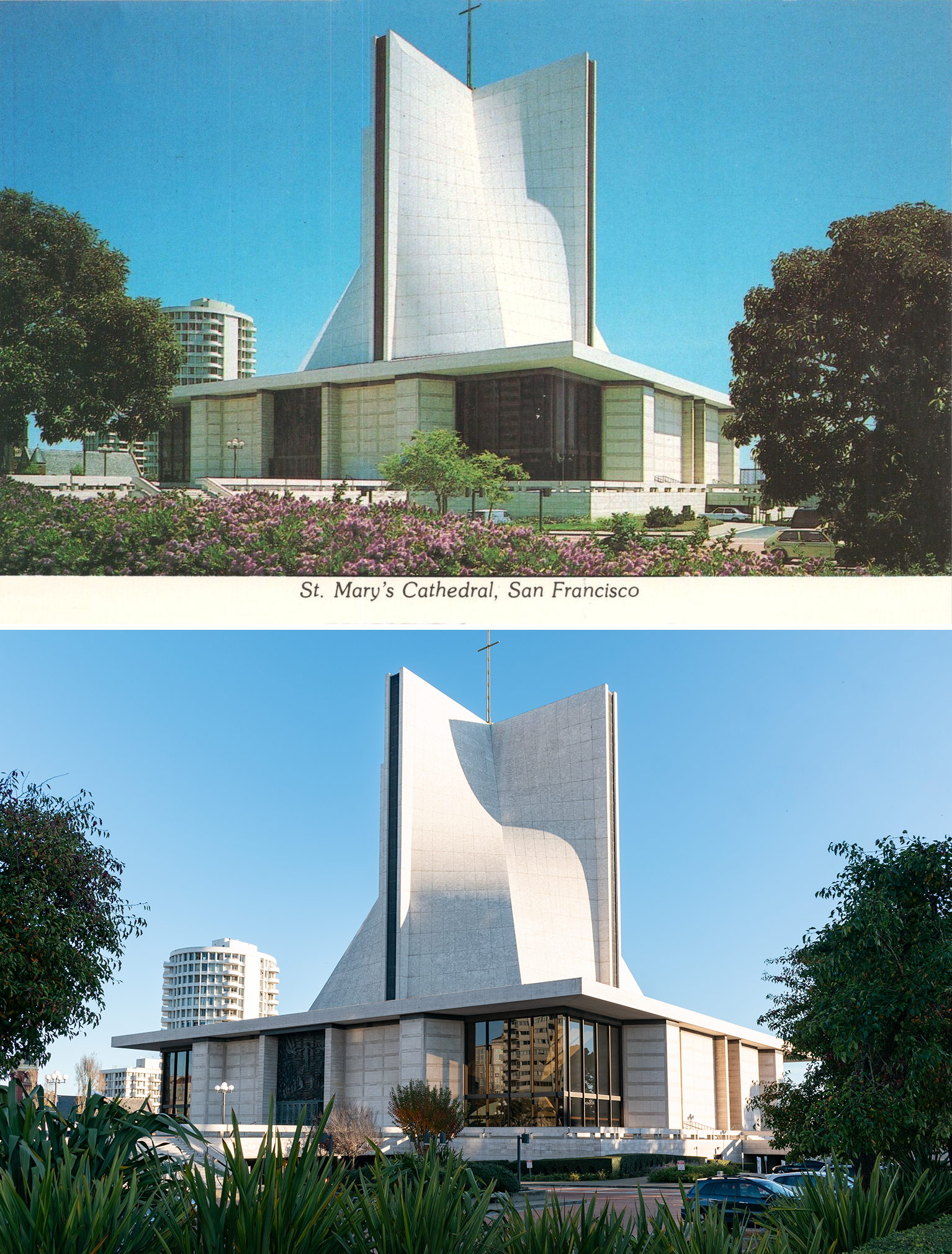

So, what’s changed in fifty-odd years? …literally nothing. I can’t spot a single substantive thing that’s different. Which, in a city that added 100,000 people and hundreds of thousands of jobs, isn’t necessarily a good thing.

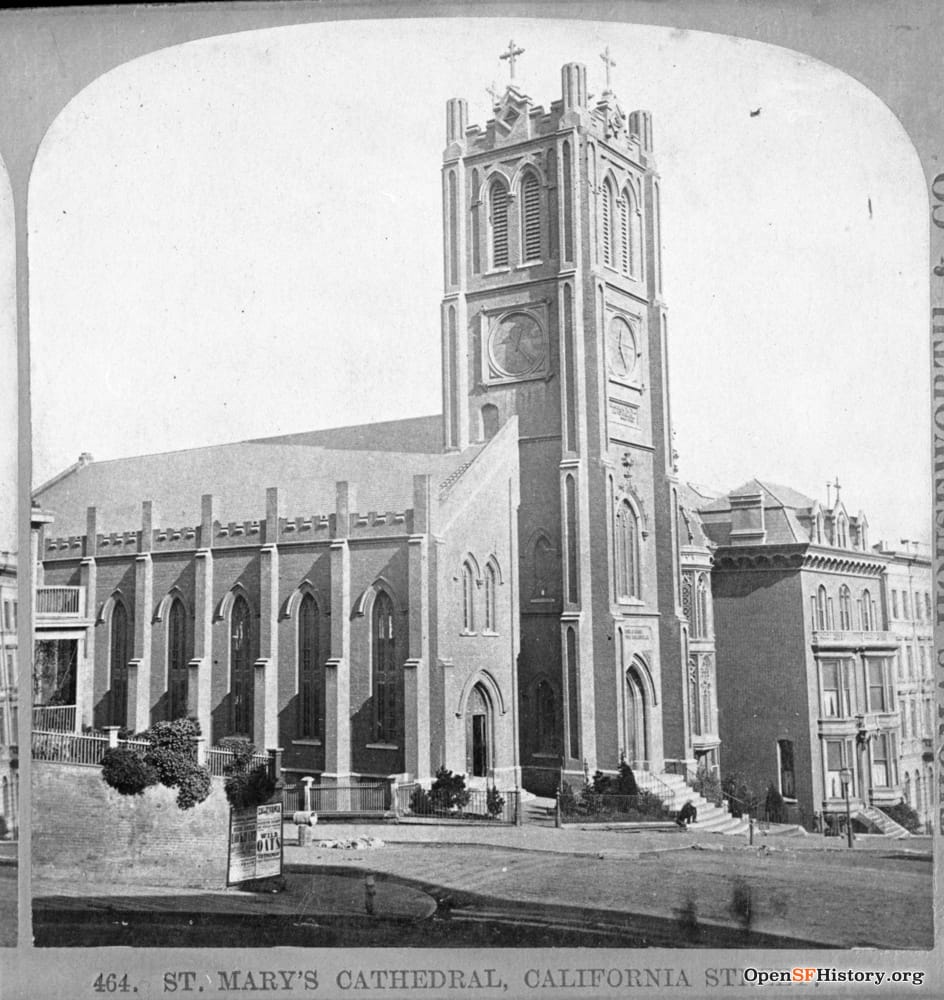

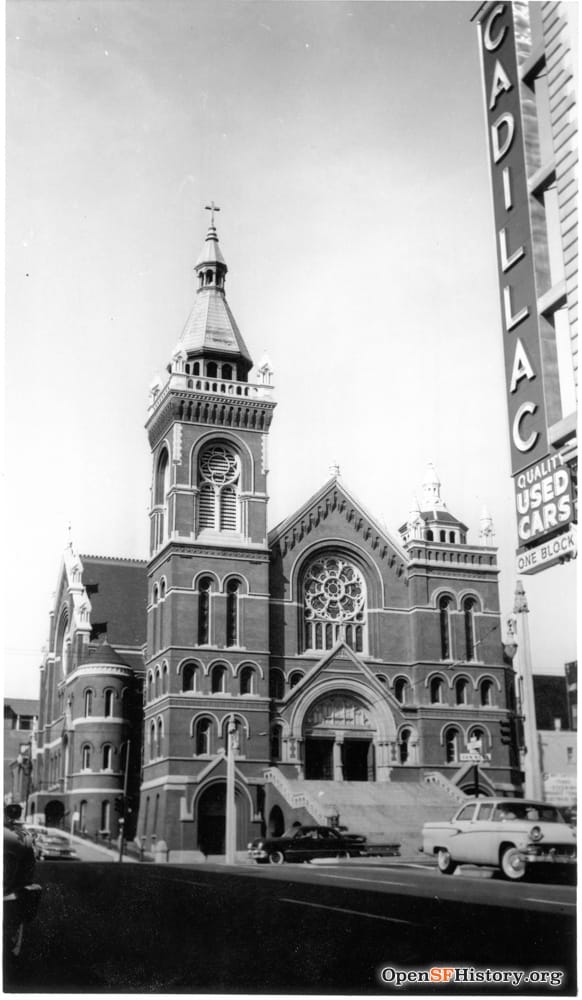

Old St. Mary’s in Chinatown was the Archdiocese of San Francisco’s first St. Mary’s Cathedral, but with the city’s Catholic population growing rapidly, within thirty years they were planning the construction of a much larger St. Mary’s Cathedral at Van Ness & O’Farrell. Opened in 1891, St. Mary of the Assumption (II) survived the big one—the 1906 earthquake and fire—but burned in a local blaze in 1962.

The first St. Mary's Cathedral (extant), ~1880 photo, OpenSFHistory / wnp37.02339-R | The second St. Mary's Cathedral, ~1910, OpenSFHistory / wnp27.7812 | St. Mary's (II), ~1960, OpenSFHistory / wnp27.6622 | 1962 article about the fire that destroyed St. Mary's II | 1960 article about the new San Francisco zoning code including parking minimums

Again, the Archdiocese basically couldn’t have rebuilt a cathedral here even if they wanted to. San Francisco’s 1960 zoning code required new churches to create one parking space for every ten seats in the building—that wasn’t going to fit on the tightly constrained lot of the torched cathedral.

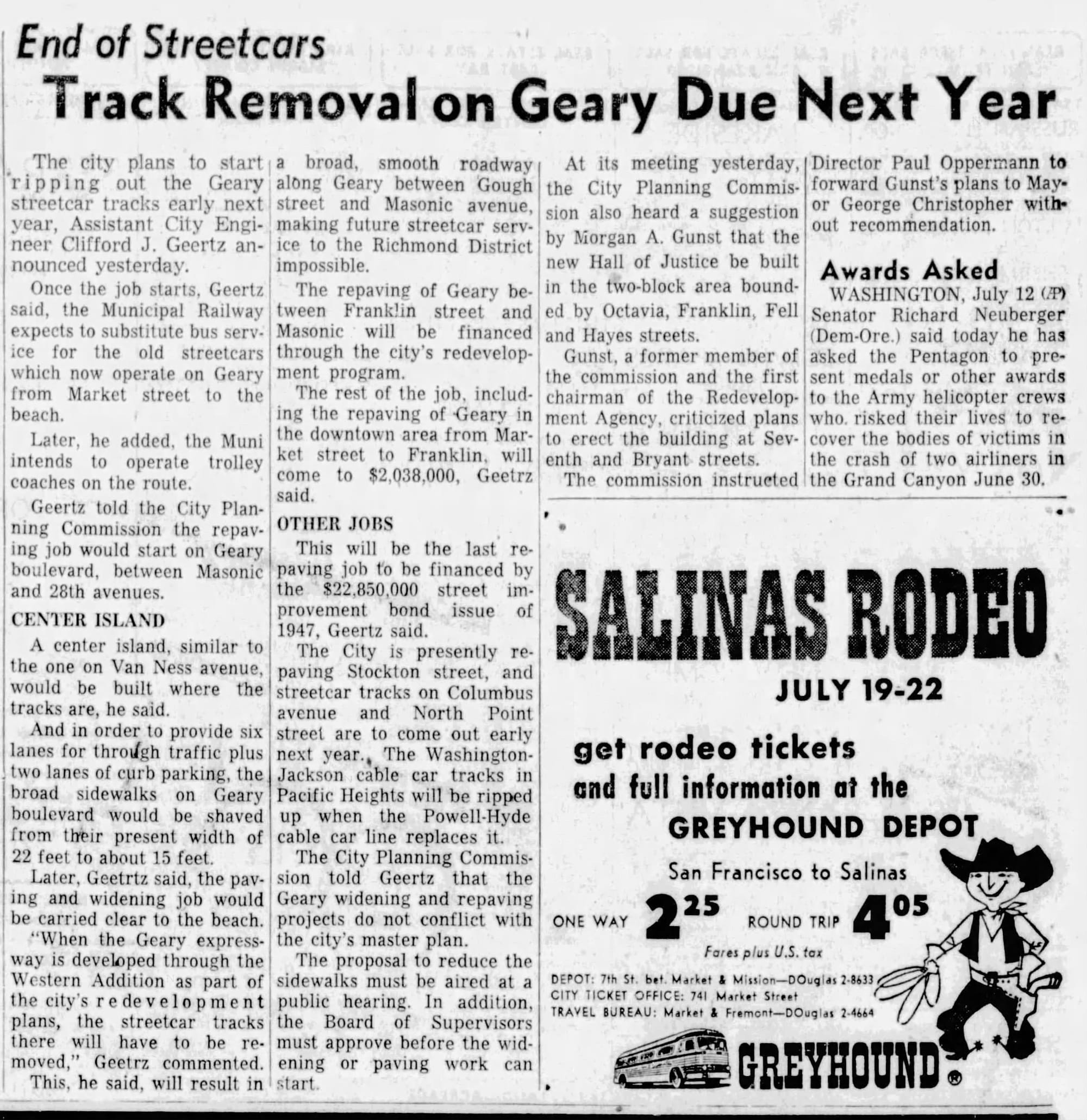

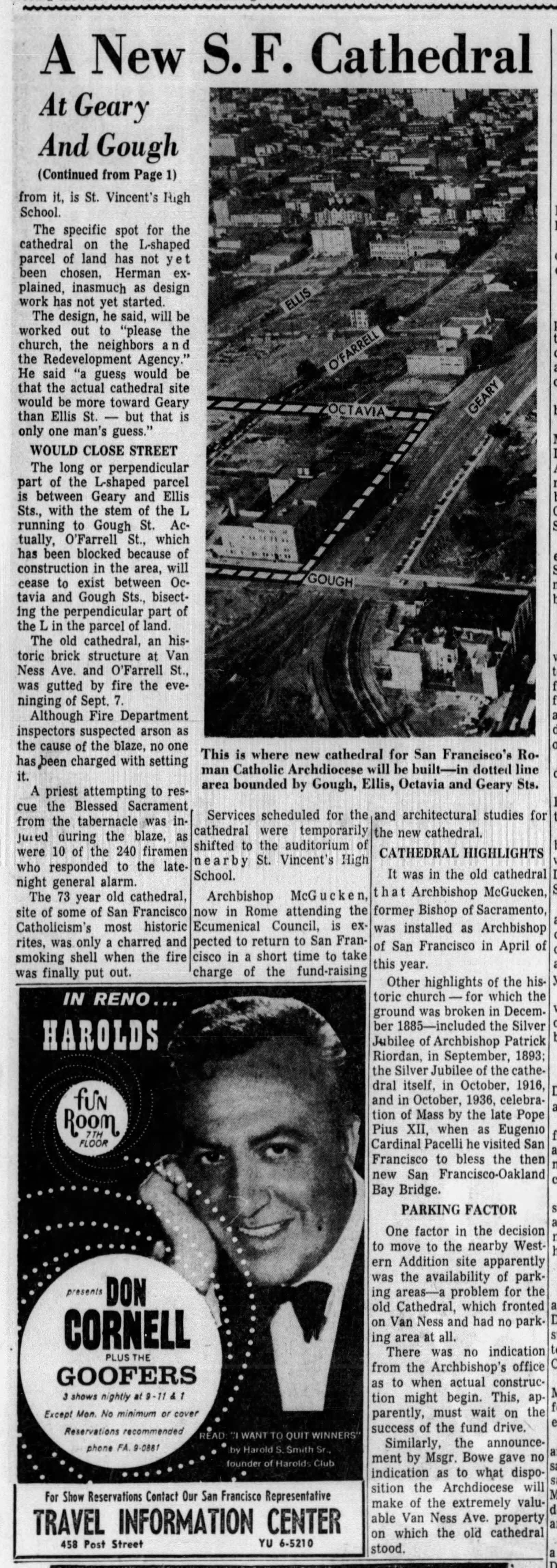

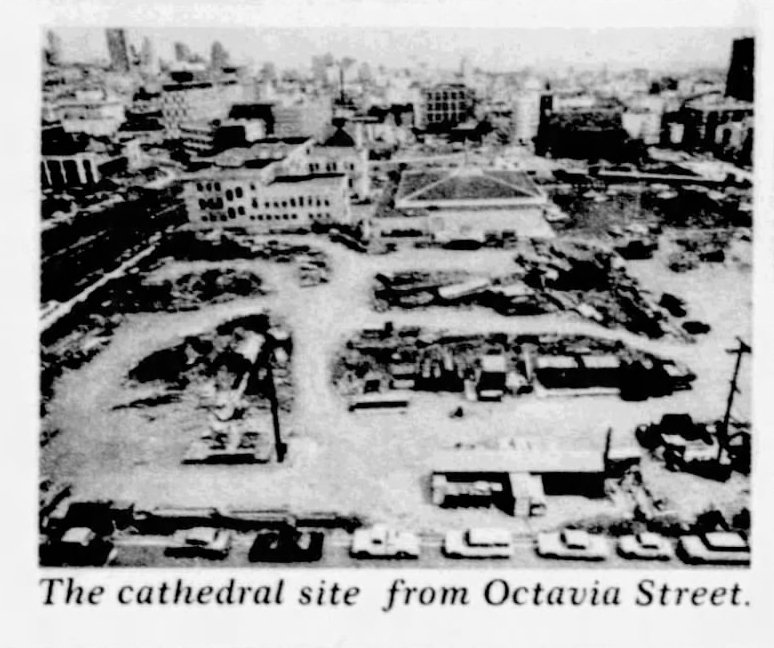

Lucky for the Archdiocese (and shittily for the people who had lived there), the San Francisco Board of Supervisors had designated the nearby Western Addition as a blighted area in 1948. The city spent much of the next decade razing the neighborhood, widening Geary Boulevard in 1957 and removing its streetcar tracks. Urban renewal claimed these particular blocks in the late 1950s, so when the Archdiocese went looking for a big plot of land for their new cathedral and parking lot, there was already a massive cleared area nearby.

Geary & Octavia, 1949, OpenSFHistory / wnp67.0616 | Block demolished in urban renewal where the church now stands, 1950, OpenSFHistory / wnp26.2018 | 1950 Sanborn Map of the block pre-urban renewal | Replanning the Geary Area in the Western Addition, 1952, the Internet Archive | 1951, Geary widening studied | 1958, Gough & Geary with cleared land, OpenSFHistory / wnp28.3739 | 1956 article about the removal of the Geary streetcar tracks | 1962 article about the new cathedral in Western Addition | 1963 article about the approval of the land sale

However, the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency had already sold the right to develop most of the land to developer Joseph Eichler. It was a complex ownership structure, but basically Eichler was paying the city a carrying fee to maintain his option and control the site. Because it was an SFRA site, Eichler couldn’t just sell the land to the Archdiocese for a profit. Through negotiation (and maybe some arm-twisting), a complex series of deals—Eichler returned the land to the SFRA for no profit, who then sold it to the Archdiocese, who swapped Eichler the old cathedral site—secured the site for the Archdiocese. (...Eichler’s company went bankrupt soon after, so it clearly didn’t work out for them.)

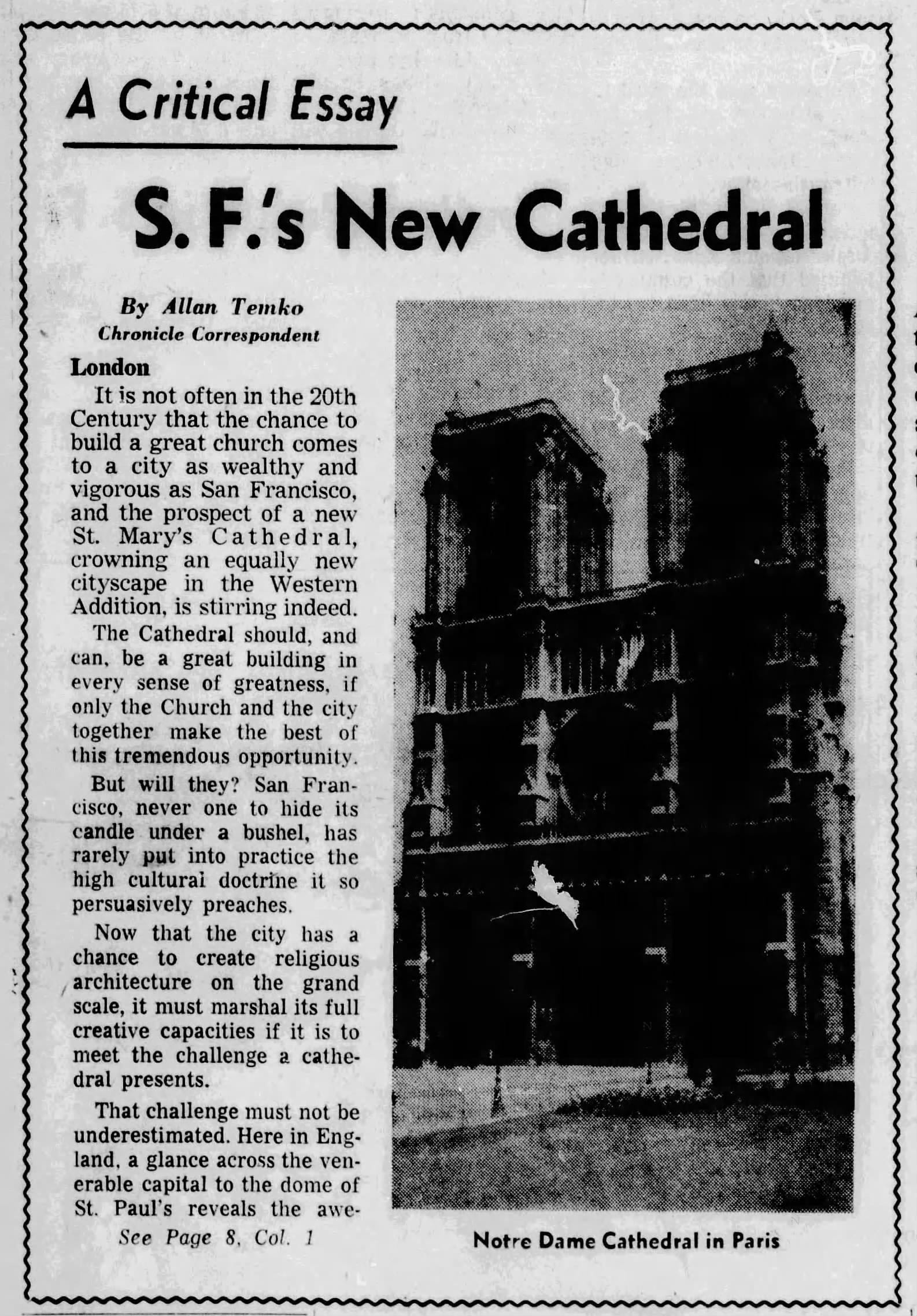

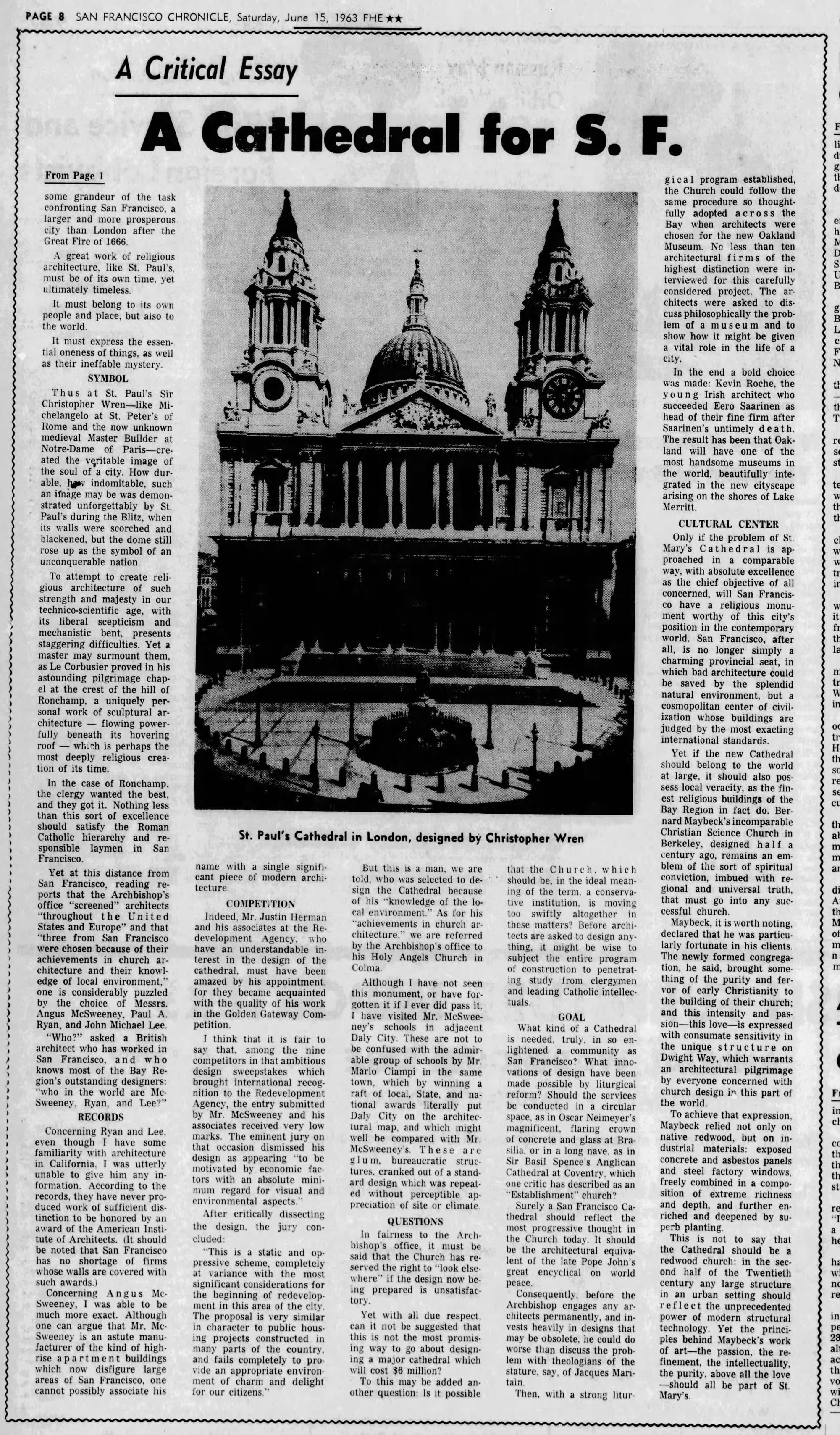

For the third St. Mary’s Cathedral, Archbishop McGucken originally envisioned something revivalist. Maybe Mission Style, perhaps something Romanesque. …lol.

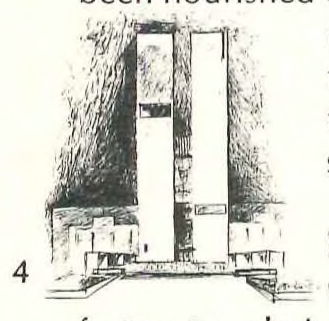

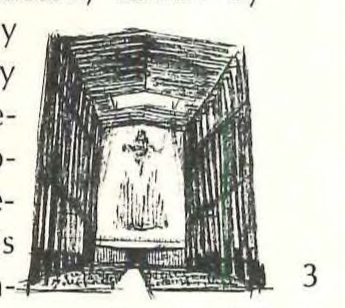

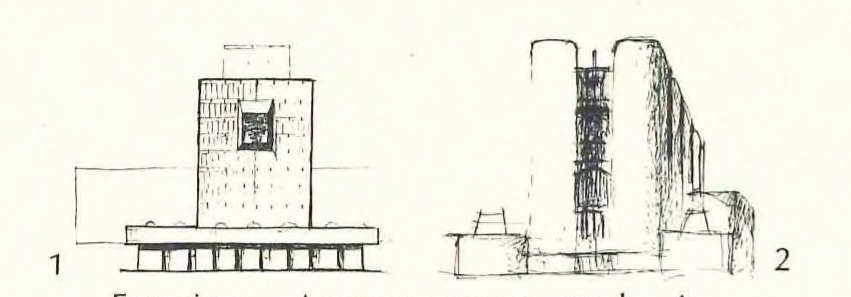

Allen Temko's withering 1963 criticism of the lack of ambition of the original plans | Early studies and sketches, Architectural Record, the Internet Archive | 1963, Archbishop McGucken with Belluschi and Nervi | 1964 articles about the new cathedral plan

To design their revivalist cathedral, the Archdiocese initially hired a relatively unassuming trio of local architects, John Michael Lee, Paul A. Ryan and Angus McSweeney. That choice—perceived to be parochial and lacking in ambition—didn’t go down well at all (with architecture critic Allen Temko particularly ruthless in his criticism). Unhappy with the architects’ initial proposals, Archbishop McGucken consulted Father Godfrey Diekmann of St. John’s Abbey in Minnesota—designed by Brutalist master Marcel Breuer—on how to proceed. With Diekmann’s encouragement, the Archdiocese of San Francisco went out and hired their modernist superstars, adding Pier Luigi Nervi and Pietro Belluschi to the project team.

Belluschi was Dean of the MIT School of Architecture, an influential modernist, and fresh off working on New York’s Pan Am Building. Nervi was a legendary Italian engineer, known for reinforced concrete wizardry, and had recently worked on the striking George Washington Bridge Bus Station in New York. Of the five headline architects who worked on St. Mary of the Assumption, only Nervi was a practicing Catholic.

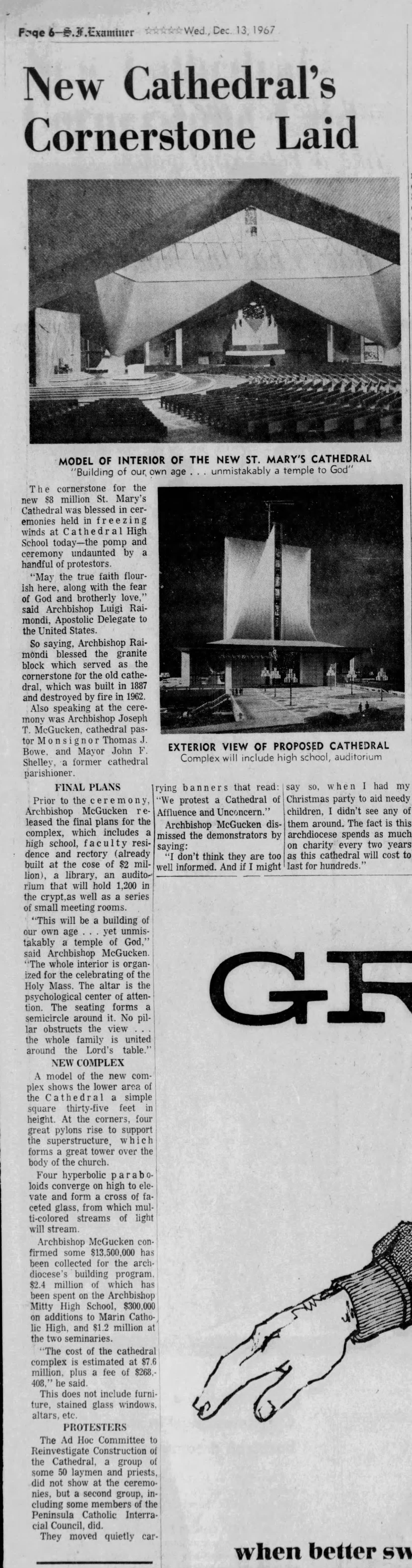

Plans for the new cathedral were coming together at a heady time for the Catholic Church. The Second Vatican Council began in 1962 and finished in 1965, codifying updates that greatly changed church practices. St. Mary of the Assumption is emphatically a Vatican II cathedral—the Archdiocese of San Francisco shifting from a traditionalist cathedral style to a modernist style just as the Catholic Church as a whole instituted reforms aimed at making Catholicism more relevant, understandable, and approachable in a changing world.

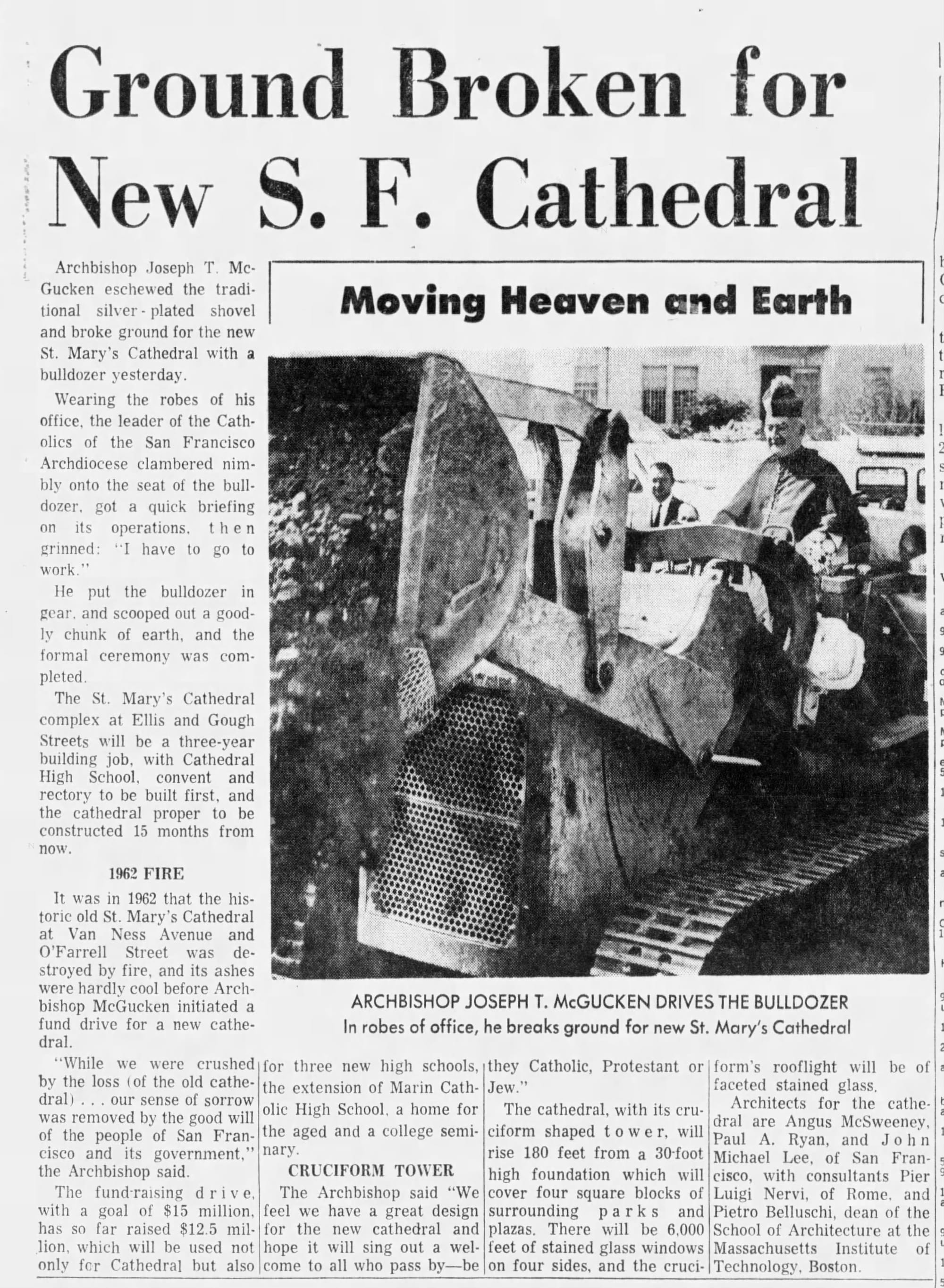

The project broke ground in 1965 and the cornerstone was laid two years later. Construction unsurprisingly went well over budget—it cost $9m (roughly $75m today)—and the high price sparked protest from Bay Area Catholics who believed that money would have been better spent on helping the poor or literally anything else. Completed in 1970, it was formally dedicated in 1971.

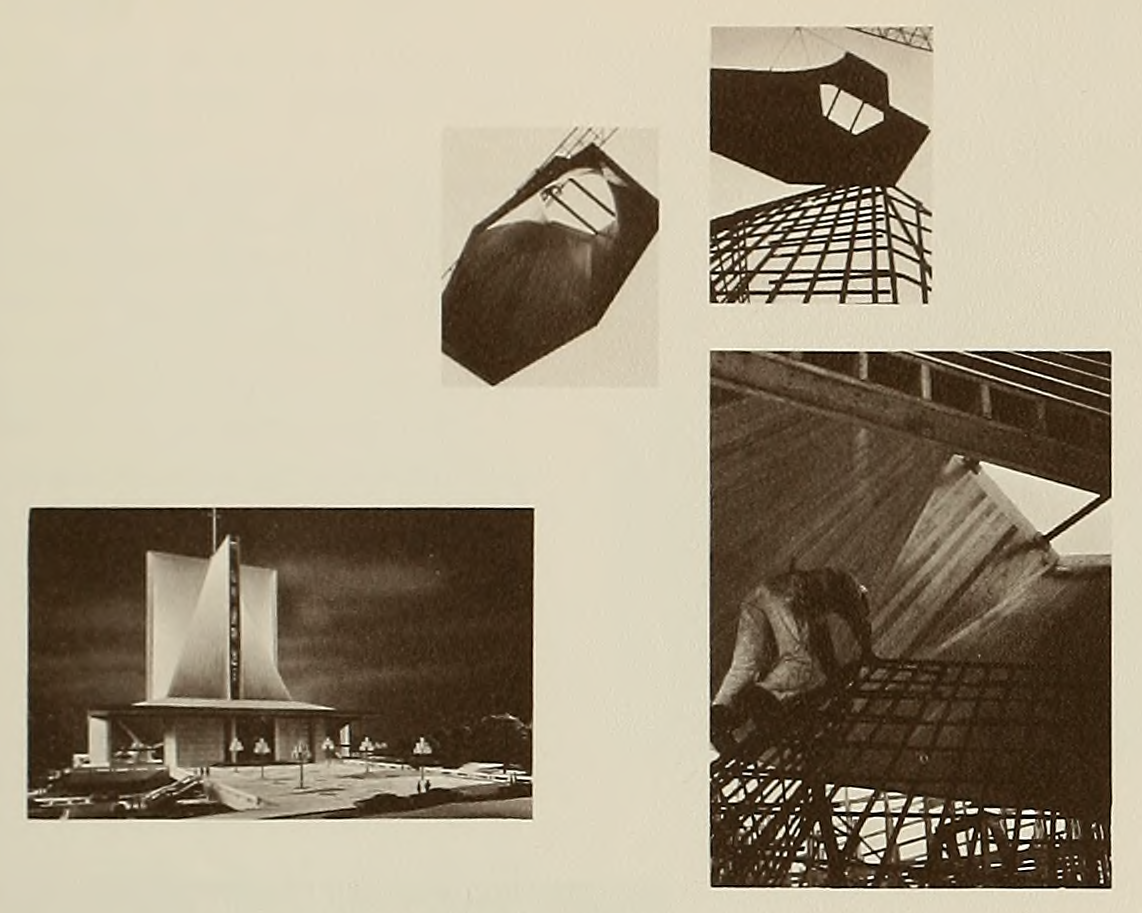

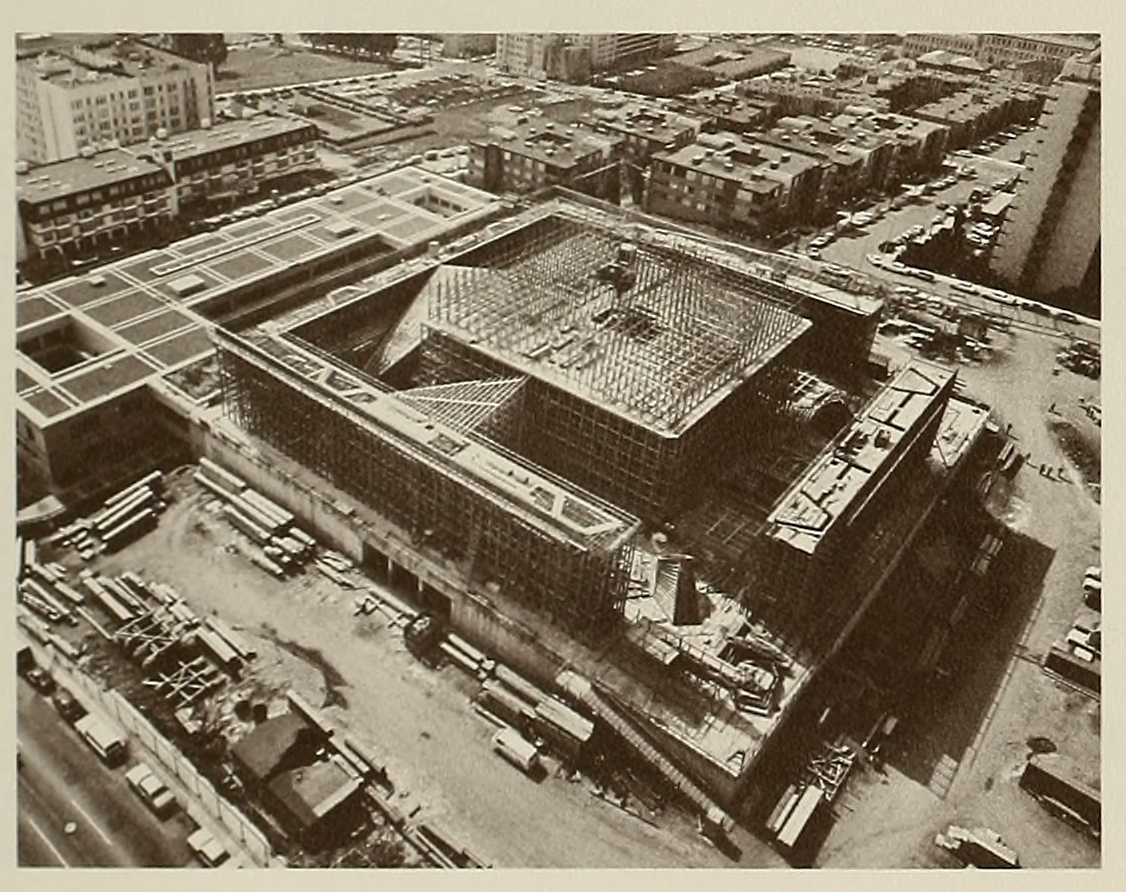

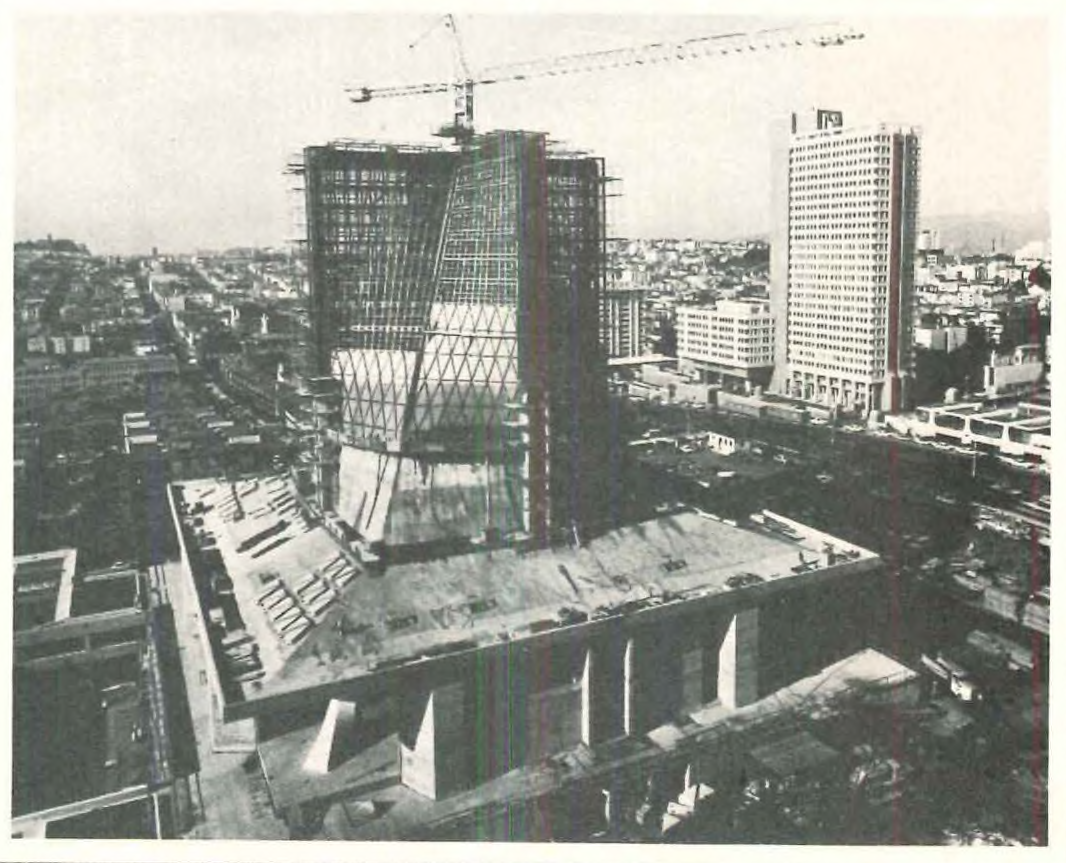

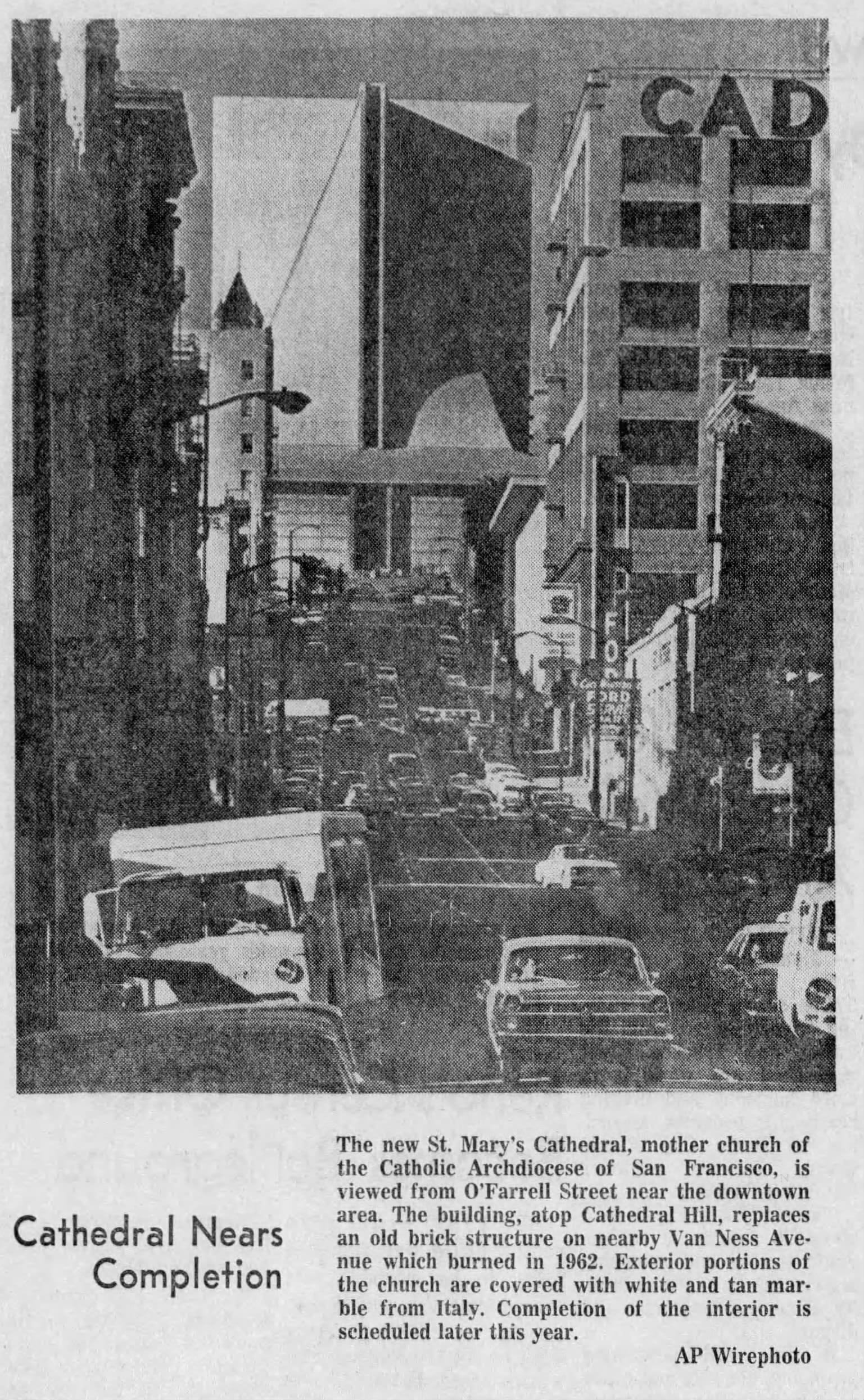

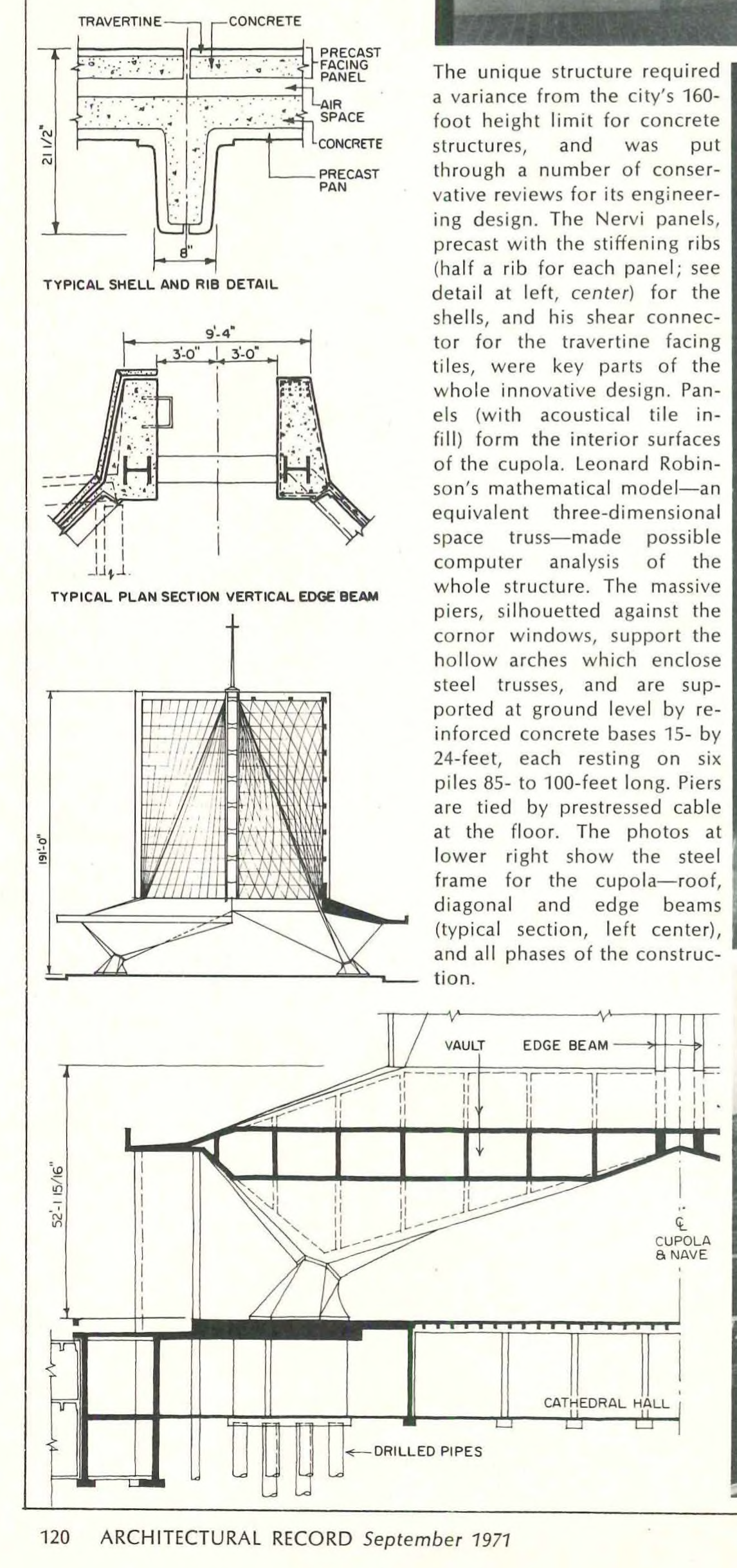

The cathedral site in the early 1960s pre-construction | 1965, groundbreaking | 1967, cornerstone laid | Construction photos and models, 1967-1968 San Francisco Redevelopment Agency Annual Report, the Internet Archive | Construction photo, Architectural Record, the Internet Archive | 1970 articles about it nearing completion and controversy | 1971, Architectural Record, the Internet Archive

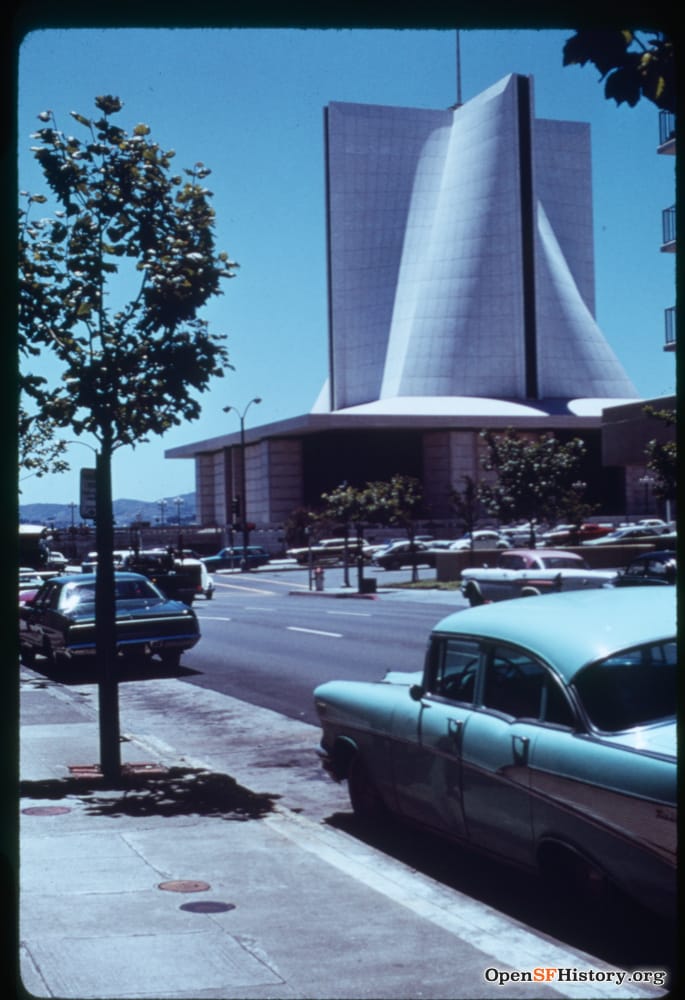

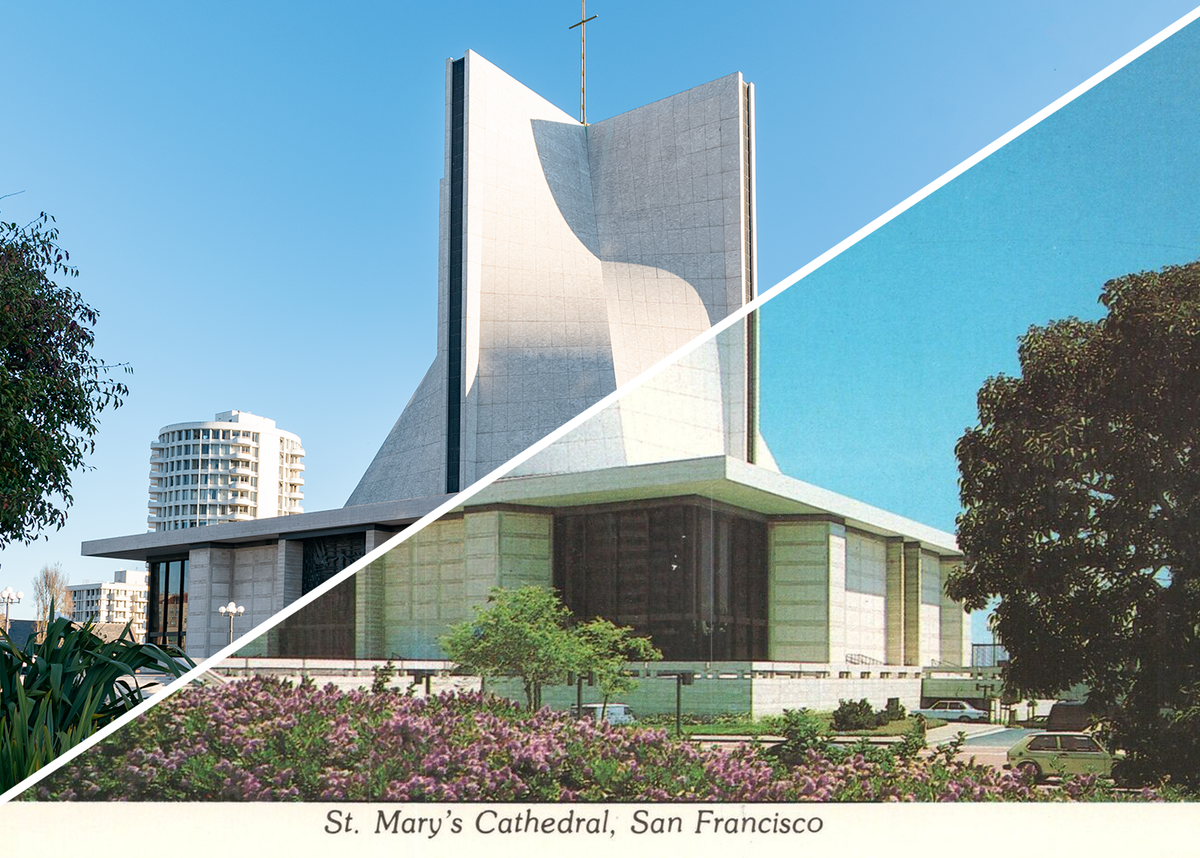

Belluschi and Nervi’s design deployed eight hyperbolic paraboloids composing a Greek Cross atop a large square base, an awesome example of structural expressionism. Steel and concrete clad in travertine, fused with geometric stained glass where the shells meet, St. Mary’s is somehow both monumental and light, bright and brutal—it’s a very cool church.

It’s also a church that looks suspiciously similar to a different St. Mary’s Cathedral that was completed a few years earlier, by Japanese architect Kenzo Tange in Tokyo. Tange had won the competition to design the Archdiocese of Tokyo’s new cathedral before San Francisco’s St. Mary’s had even burned down. Completed in 1964, Tange also used eight hyperbolic paraboloids to create an austere cross-shaped church—in this case, the concrete shells were clad in stainless steel rather than travertine and San Francisco’s cathedral is more than twice as large, but the effect is strikingly familiar. The architecture world speculated at the time about plagiarism, and the pastor of San Francisco’s St. Mary’s—Monsignor Thomas J. Bowe—even asked Nervi whether he’d copied Tange’s design (Nervi said no). Personally, I lean towards convergent evolution—hyperbolic paraboloids were having a bit of a moment—plus perhaps a little subconscious inspiration.

Ad for Tange's St. Mary's in Tokyo in Architectural Record, 1969, the Internet Archive | St. Mary of the Assumption, San Francisco, 2023

Compared to an agitator in the inside of a washing machine, ”Our Lady of Maytag” is also blessed with a famous shadow, the Two O'clock Titty. Over the last fifty or so years, St. Mary’s has grown into a modernist landmark (albeit one that feels a little overlooked nationally?). It’s also the source of this neighborhood’s (still newish) name—Cathedral Hill. And those parking requirements that forced St. Mary’s to move here in the 1960s and wrap itself in a giant parking lot? The City of San Francisco abolished them in 2018, part of a broader (and still contested) national movement to dump the inflated parking minimums that helped flatten American cities into lifeless parking lots.

1980, Carol Highsmith, Library of Congress | 2012, Carol Highsmith, Library of Congress | 1938 aerial, Harrison Ryker, San Francisco Public Library | 2024 aerial, Google Earth

Production Files

Further reading:

- Beauty's Rigor: Patterns of Production in the Work of Pier Luigi Nervi by Thomas Leslie

- St. Mary's in Architectural Record in 1971

- On broader Western Addition urban renewal project in Architectural Record in 1965

A few more interesting figures from the 1971 Architectural Record article.

And a couple more neat photos.

1970, OpenSFHistory / wnp25.3512 | 1971, OpenSFHistory / wnp25.3523 | 1971, OpenSFHistory / wnp25.3522 | 2023

Member discussion: