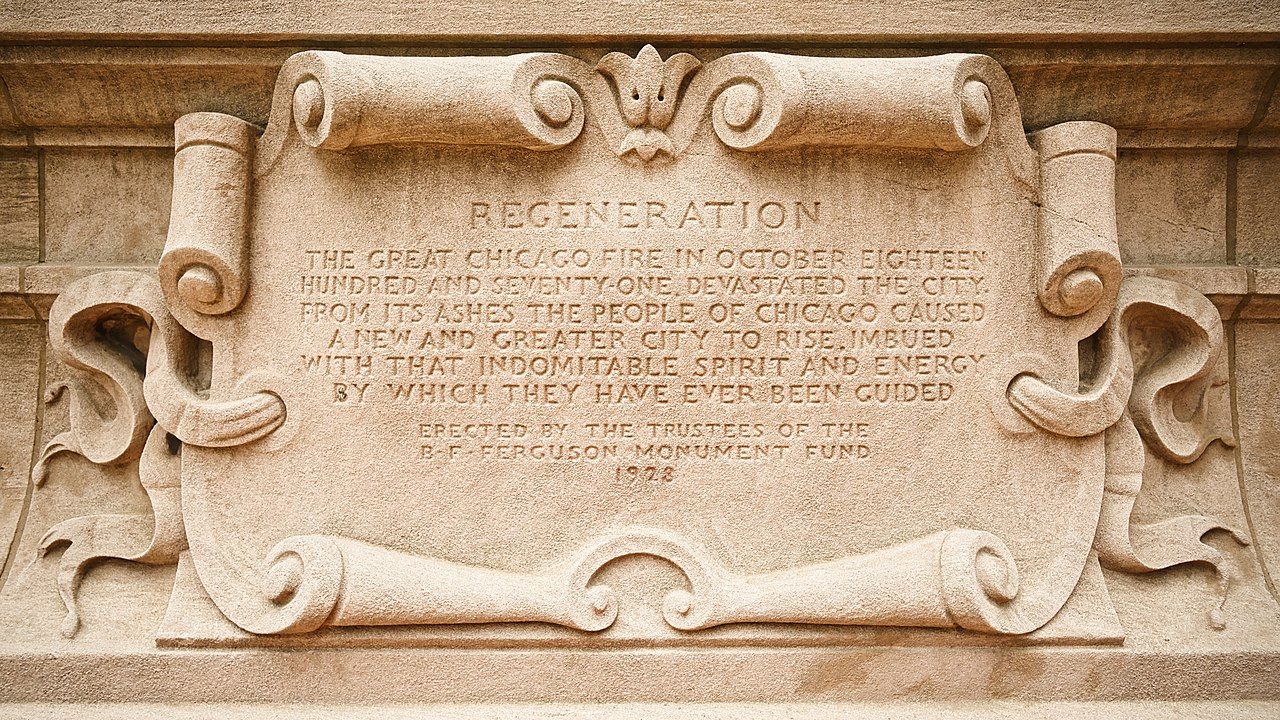

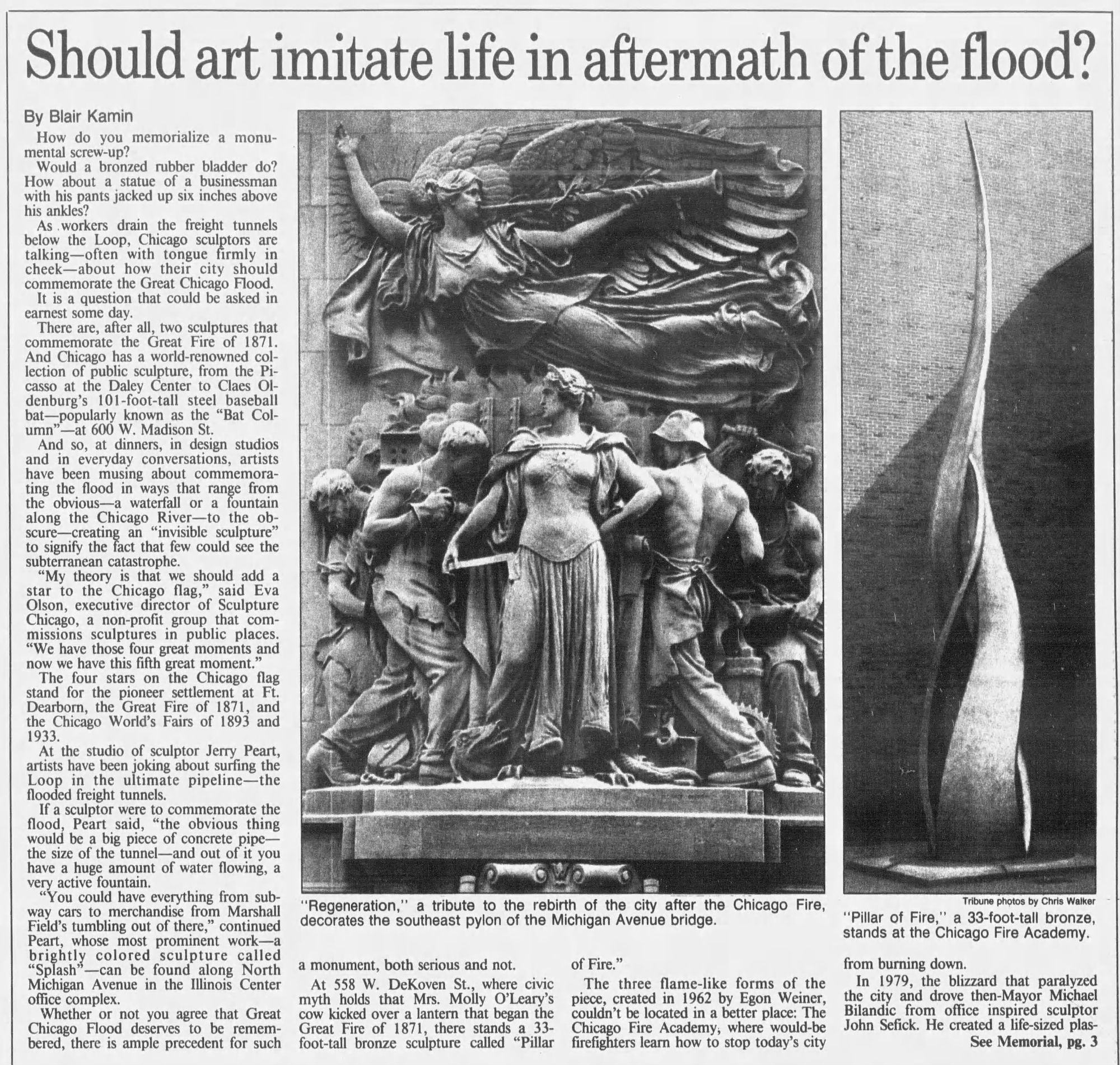

Sculptor Henry Hering’s Regeneration is one of four relief sculptures installed in 1928 on the tender houses of the DuSable Bridge, paid for by the B.F. Ferguson Monument Fund–a unique Chicago civic sculpture endowment. Symbolizing the rebuilding of Chicago after the Great Fire of 1871, in 2022 Regeneration and the three other bridgehouse reliefs were recommended for removal by the Chicago Monuments Project, a racial healing and historical reckoning initiative that evaluated Chicago’s memorials, monuments and public art.

I suspect that Regeneration’s inclusion on that list was mostly collateral damage, guilt-by-association. In recommending the bridgehouse reliefs for removal, the commission pointed to their imperialist triumphalism, depicting Native Americans only as tools to define the heroic acts and qualities of colonizers. Which, yeah. The other reliefs–Pioneers, the Defense, and Discoverers –range from distasteful to appalling. Regeneration, though, is a pretty innocuous representation of men rebuilding the burning city around the “I Will” personification of Chicago, who’s holding a carpenter’s square and stepping on a salamander. It’s hard to see how that conveys a narrative of Western colonial triumph, besides its proximity to and relationship with the other three (would be weird to remove three and leave one). The point is likely moot anyway–the legal status of the bridge as a Chicago landmark and the reliefs’ physical incorporation into the bridgehouses would make removal very complicated.

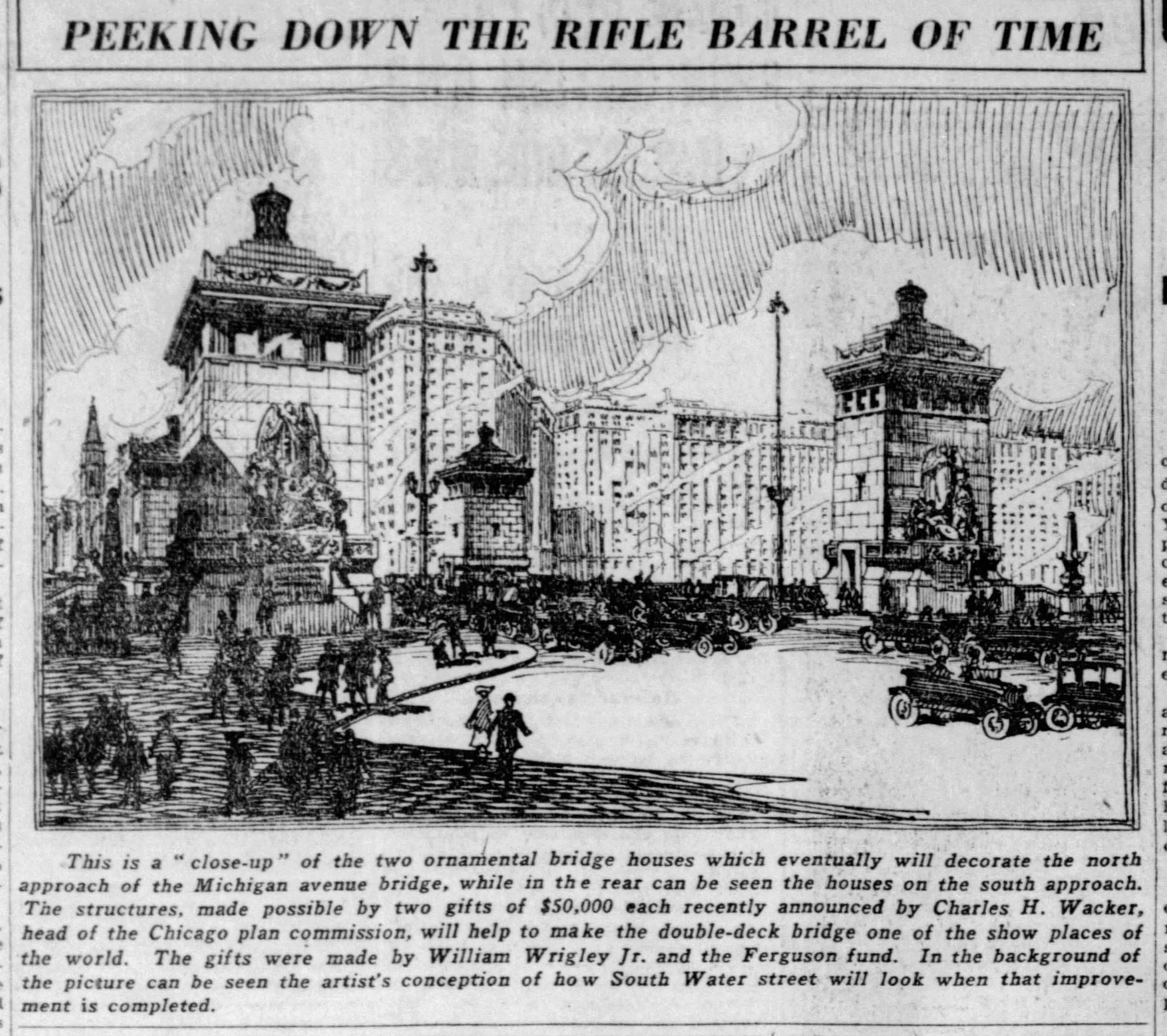

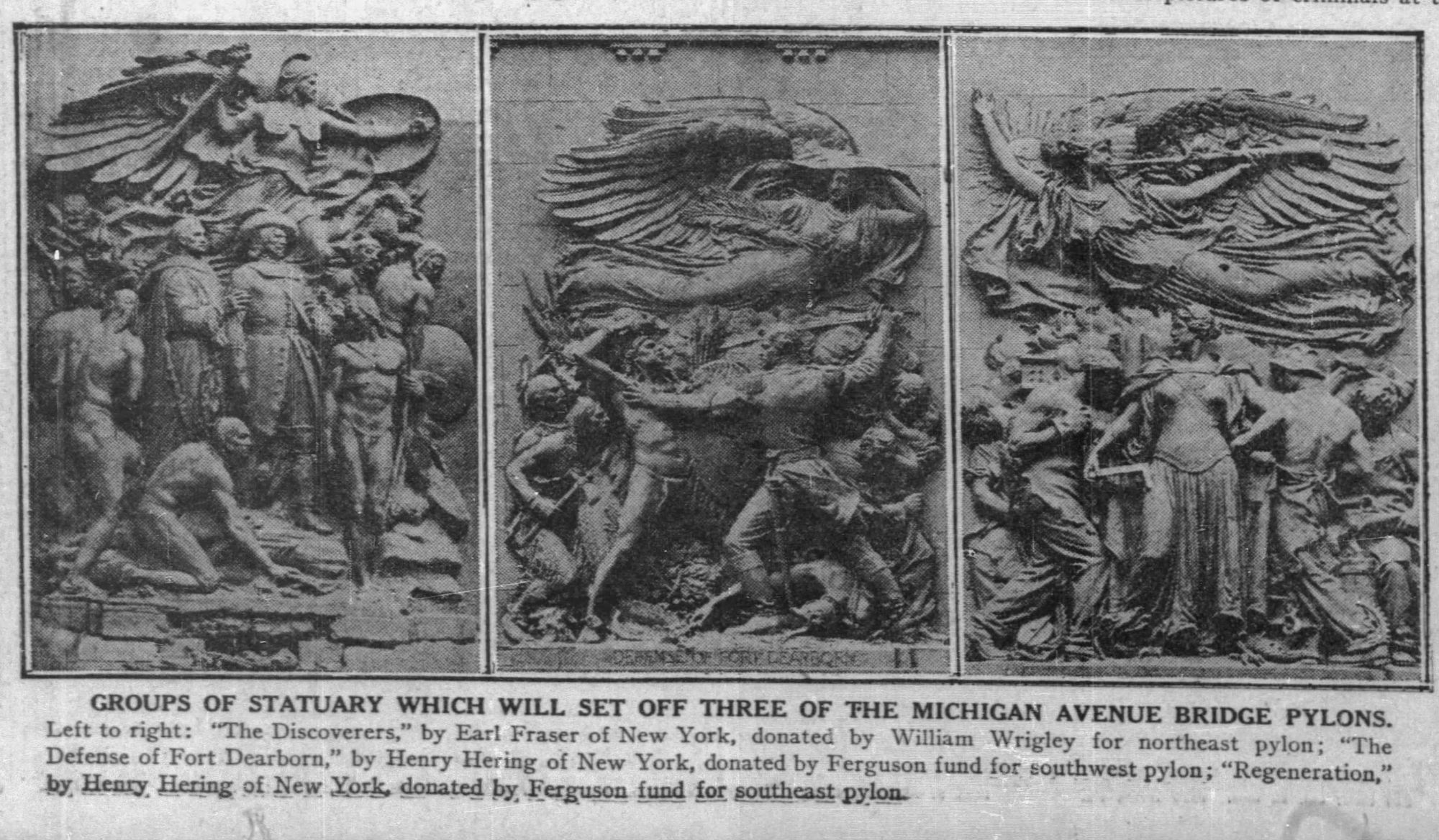

Designed by architect Edward Bennett with engineers Thomas Pihlfeldt, Hugh Young and William Mulcahy, the Michigan Avenue Bridge was completed in 1920. The tender houses were conceived as classical pylons, grand Beaux Arts canvases for architectural sculpture. For the first few years, they were blank canvases–sculptors Henry Hering (southern pylons) and James Earle Fraser (northern pylons) won the commission to decorate the tender houses in 1922, which were installed in 1928.

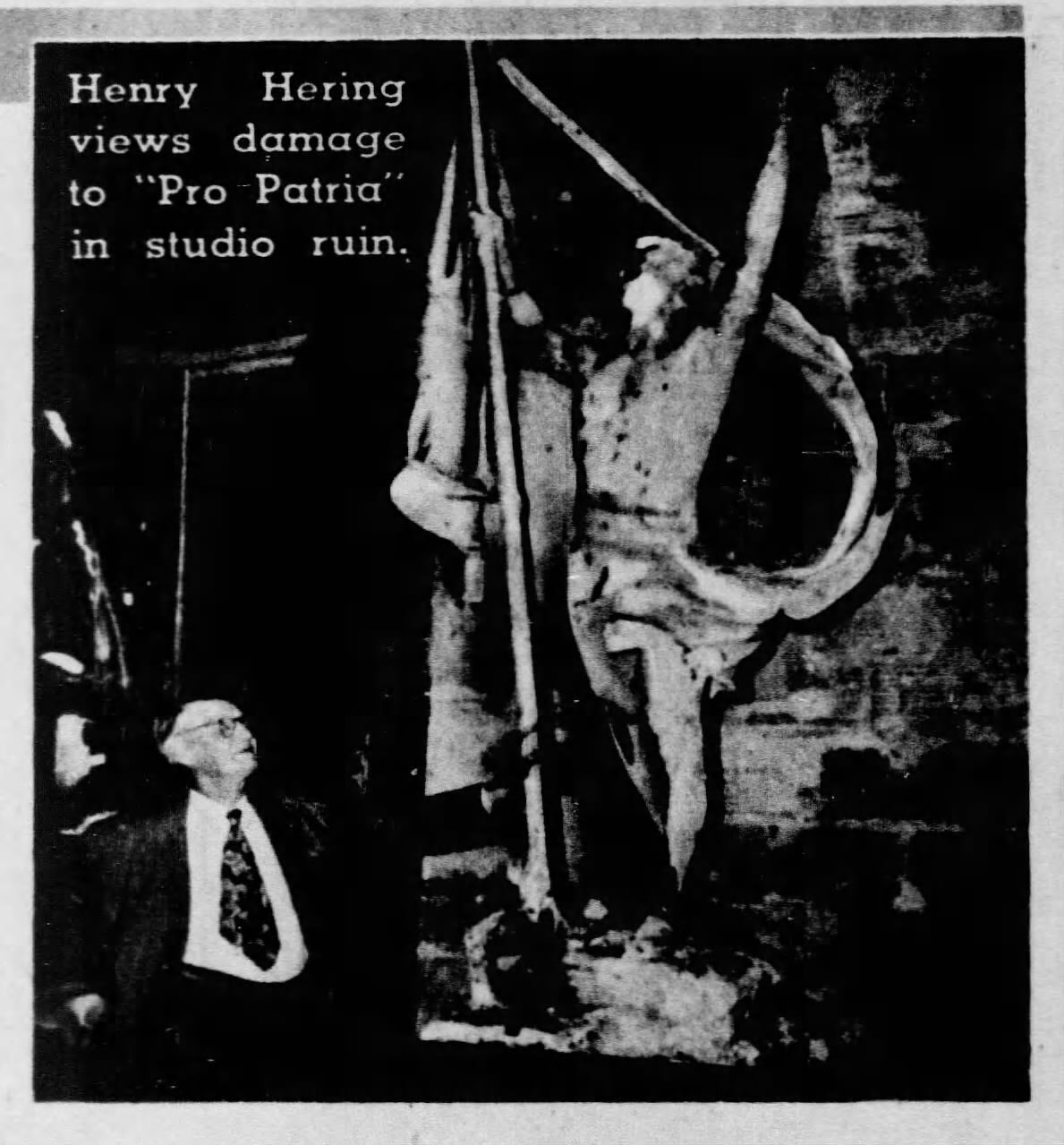

Hering was one of the premier architectural sculptors of the early 20th century. Most of his work is kind of bland, technically-accomplished Beaux Arts (you can see it at the Field Museum and Chicago Union Station), but in the 1930s he knocked it out of the park with some terrific Art Deco. Hering is undoubtedly the only sculptor with a major professional sports team named after one of his works–Hering sculpted the iconic Guardians of Traffic on Cleveland’s Hope Memorial Bridge, which gave the Cleveland Guardians baseball team their name.

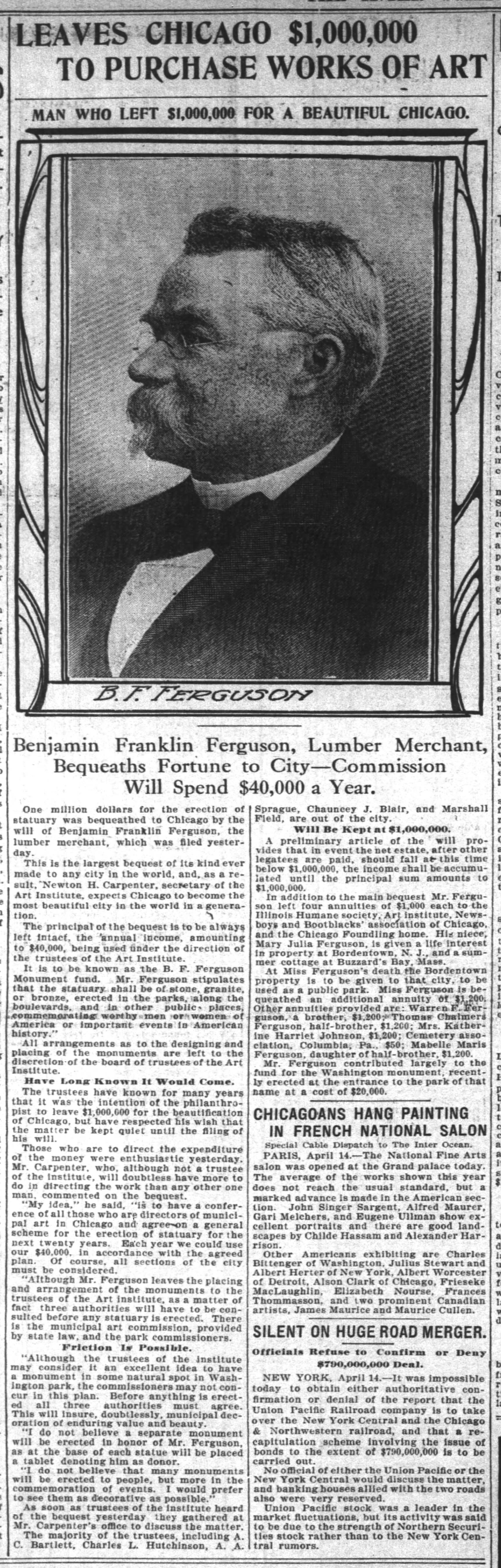

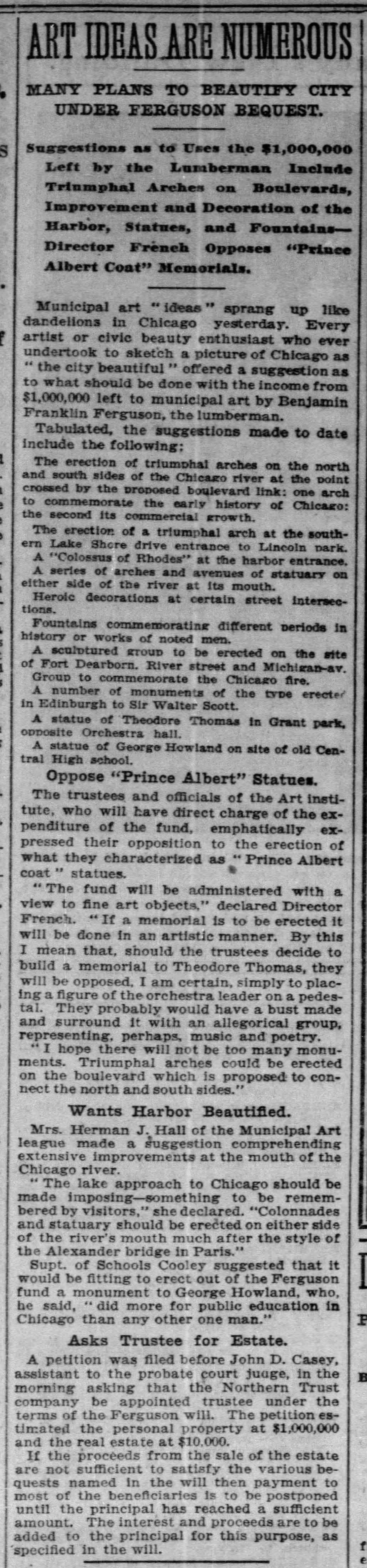

I’m fascinated by the story of the B.F. Ferguson Monument Fund, which paid for the two Hering reliefs on the southern pylons, Regeneration and the Defense (William Wrigley paid for the northern two by James Earle Fraser). Benjamin Franklin Ferguson was a Chicago lumber baron (his mansion at 1501 W. Jackson Boulevard still stands) who left $1m ($35m today) on his death in 1905 to endow a fund dedicated to building and maintaining public monuments in Chicago. His will directed the board of trustees of the Art Institute to administer the fund, which went fine…initially.

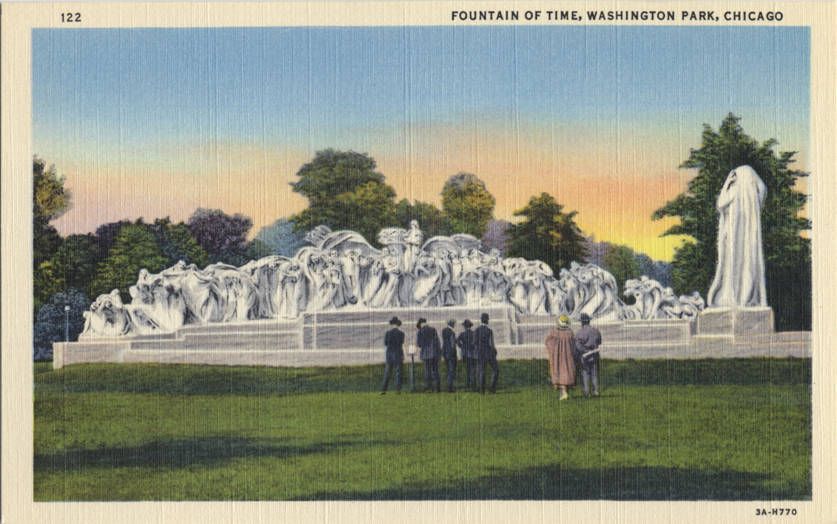

In its first few decades, the Ferguson Monument Fund paid for some of Chicago’s best, most beloved public art, including Lorado Taft’s incredible cast-concrete Fountain of Time, Logan Square’s Centennial Monument, and Taft’s Fountain of the Great Lakes (...also some blah and bad ones, like a boring Alexander Hamilton monument and a problematic Jacques Marquette memorial).

The abuse of the Ferguson Fund began in the 1930s, first cautiously, with the trustees pushing the envelope of what constituted “public” by installing the Ferguson-funded Fountain of the Tritons by Carl Milles in their (private) courtyard in 1931. Then, with the museum’s budget trashed by the Great Depression, more brazenly, the trustees basically asking, “hey, can a monument be…a building? …our building, perhaps?”.

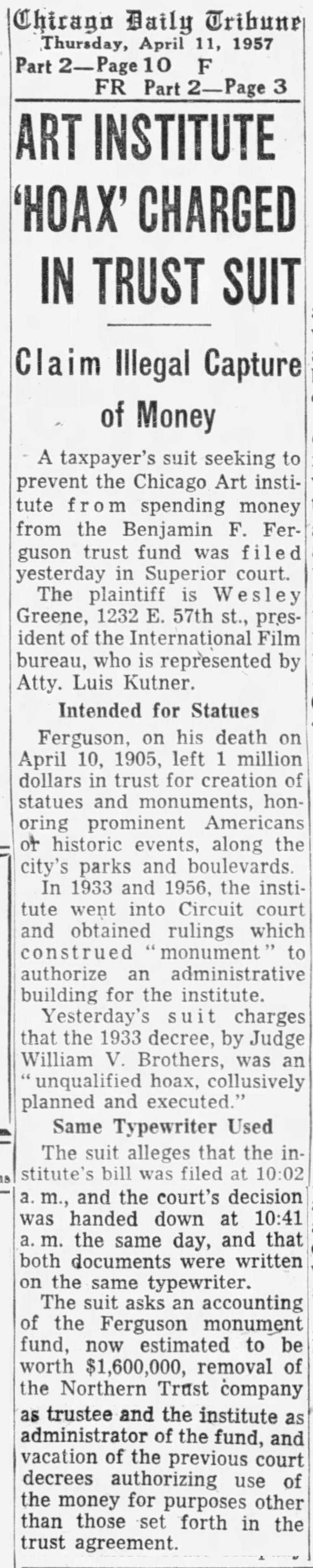

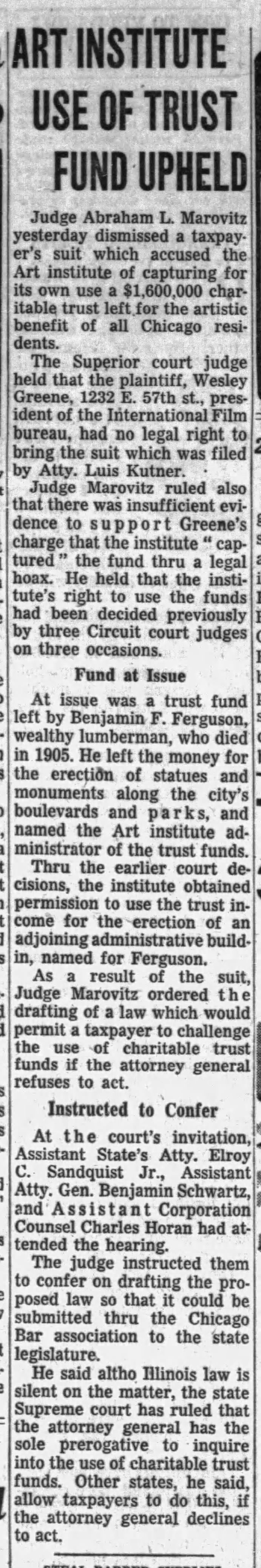

The fund, which paid for a dozen monuments in its first 25 years, didn’t commission anything between 1932 and 1966. Instead, the Art Institute used those decades of income to build itself a new administrative wing in the 1950 that they named–of course–the Ferguson Memorial Building. People were pissed, and multiple groups sued, including lawyer Luis Kutner and archivist Wesley Greene. While their suits were all thrown out for lack of standing, in response to Greene and Kutner’s suit Judge Abraham Lincoln Marovitz told the museum’s lawyers, “I cannot agree that Ferguson intended for the income to be used to erect an administration building.” However, the only one with standing to challenge the misuse of the Ferguson trust fund was the Illinois Attorney General, Latham Castle, who for whatever reason was not interested. In response, the Illinois legislature passed the Charitable Trust Act in 1961, which permitted any taxpayer to challenge an institution’s use of a charitable trust fund.

Their main goal accomplished and spooked by the public pressure, the Art Institute once again began using the Ferguson Monument Fund for its stated purpose. Amongst others, the fund paid for Henry Moore’s Nuclear Energy at the site of the first controlled nuclear chain reaction on the University of Chicago campus, a Louis Bourgeois monument to Jane Addams, and George Segal’s Man on a Bench at IIT.

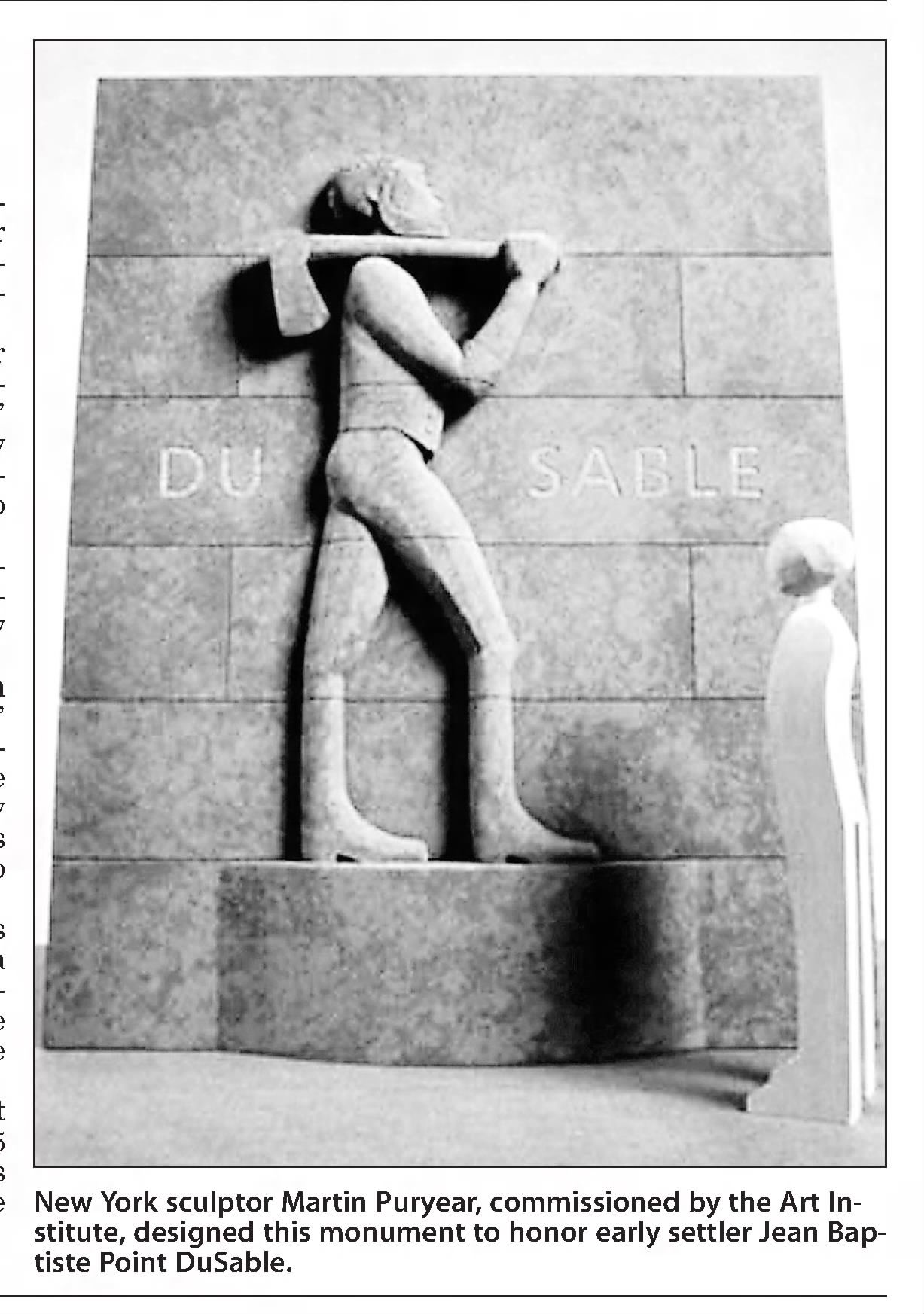

The last Ferguson Fund monument, a sculpture honoring Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable by Martin Puryear, was commissioned in 1998. DuSable Park, first announced in 1987 by Mayor Harold Washington, still doesn’t exist–so Puryear’s sculpture has never been installed, and I’m not 100% sure it was ever completed. The unfortunate irony is that in his will Ferguson prohibited the fund from investing in equities, so the fund mostly missed the stock market boom of the last forty years–basically, the Art Institute finally started using the fund for its rightful purpose right when its income entered a period of relative decline.

Production Files

Further reading:

- The Landmark Designation Report for the Michigan Avenue Bridge, including Hering's Regeneration

- The final report of the Chicago Monuments Project with their recommendation to remove the four relief sculptures on the bridgehouses, including Regeneration

- Fantastic 1997 Chicago Reader article on the use and misuse of the Ferguson Monument Fund

- 1962 article in Focus Midwest about the legal conflict around the Art Institute using the Ferguson Fund on an administration building

- DePaul University Law Review article, "The Desecration of the Ferguson Monument Trust: the Need for Watchdog Legislation"

- Interesting journal article on one of the last Ferguson Monument Fund commissions, Louise Bourgeois' Helping Hands monument to Jane Addams, "Public Art Chronicles: Louise Bourgeois' Helping Hands and Chicago's Identity Issues"

- "The Work of Henry Hering", in Architectural Record in 1912

- 2000 Chicago Reader article on the Martin Puryear commission that still hasn't been installed (...does it even exist?)

Member discussion: