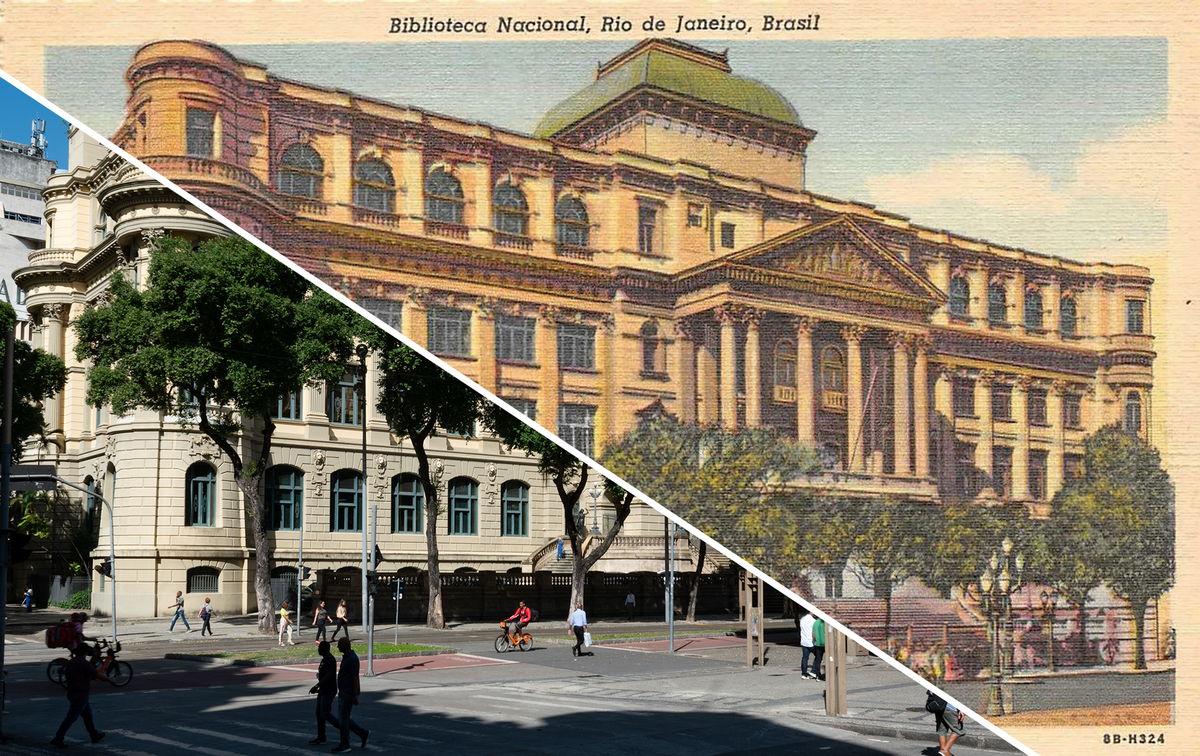

Brazilian eclecticism like the National Library in Rio de Janeiro so embarrassed famous modernist Lucio Costa that when Brazil’s National Historic and Artistic Heritage Institute listed the building in 1973 he fought to strip credit from Francisco Marcelino de Sousa Aguiar and pin it on an obscure French architect, Hector Pepin.

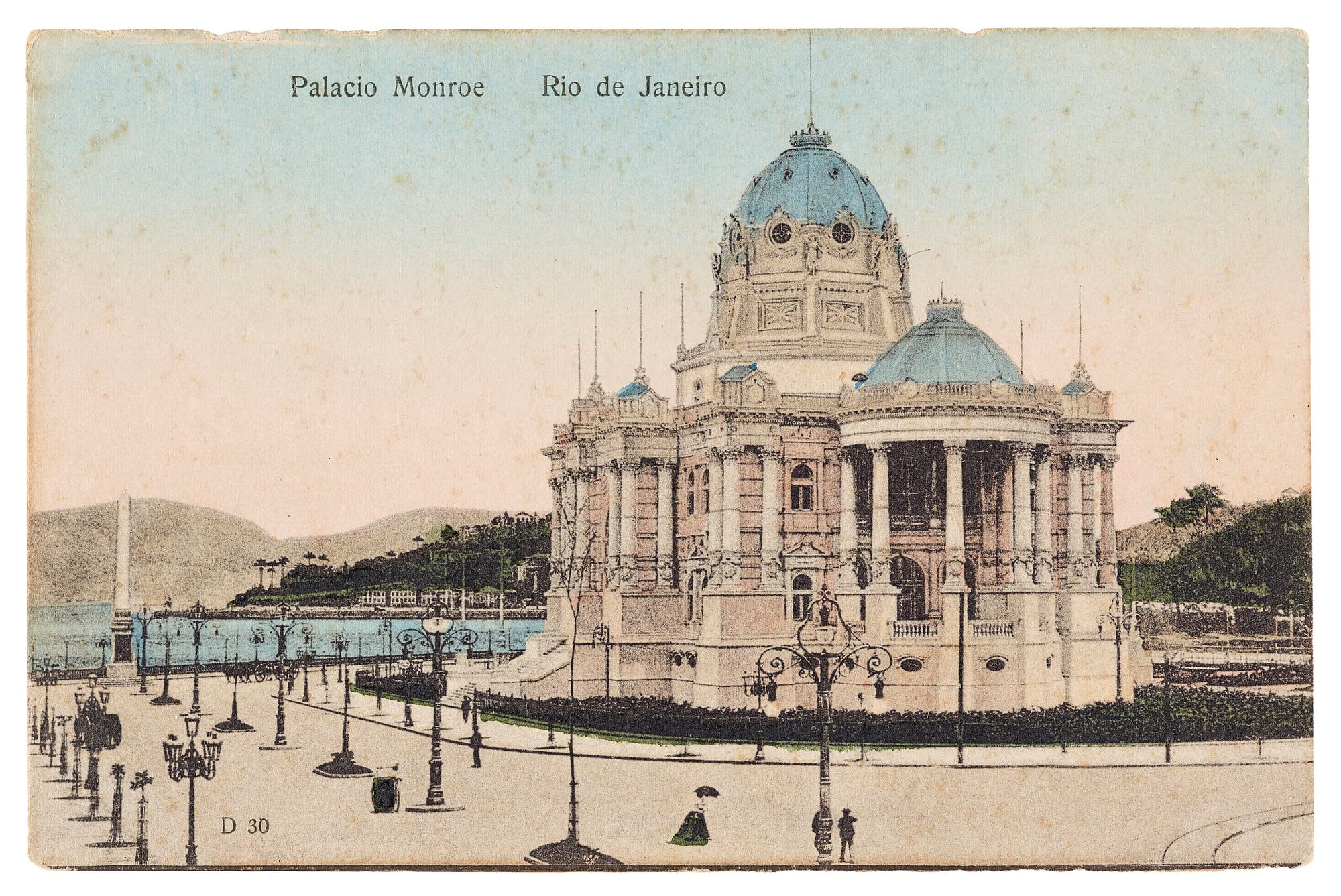

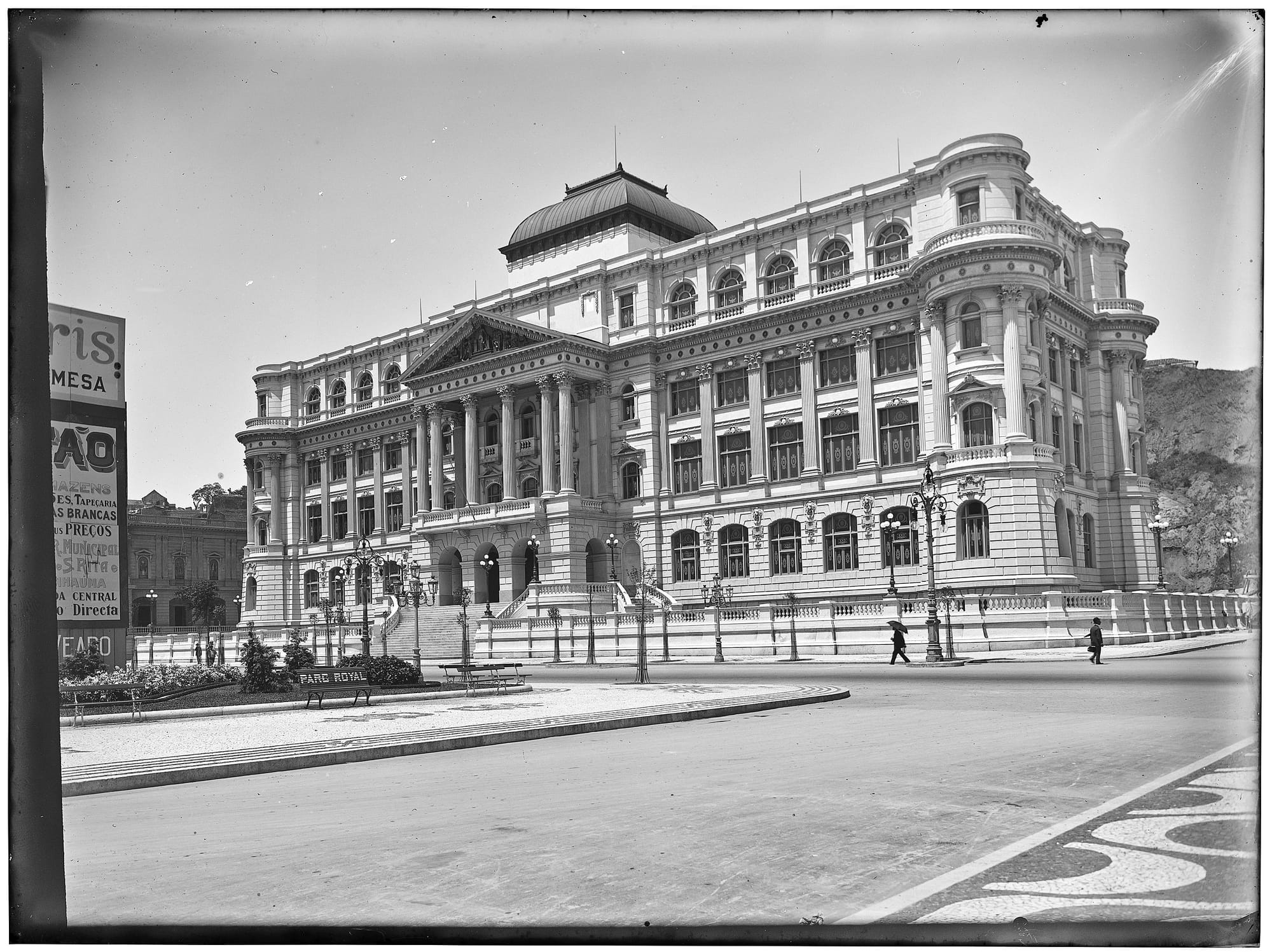

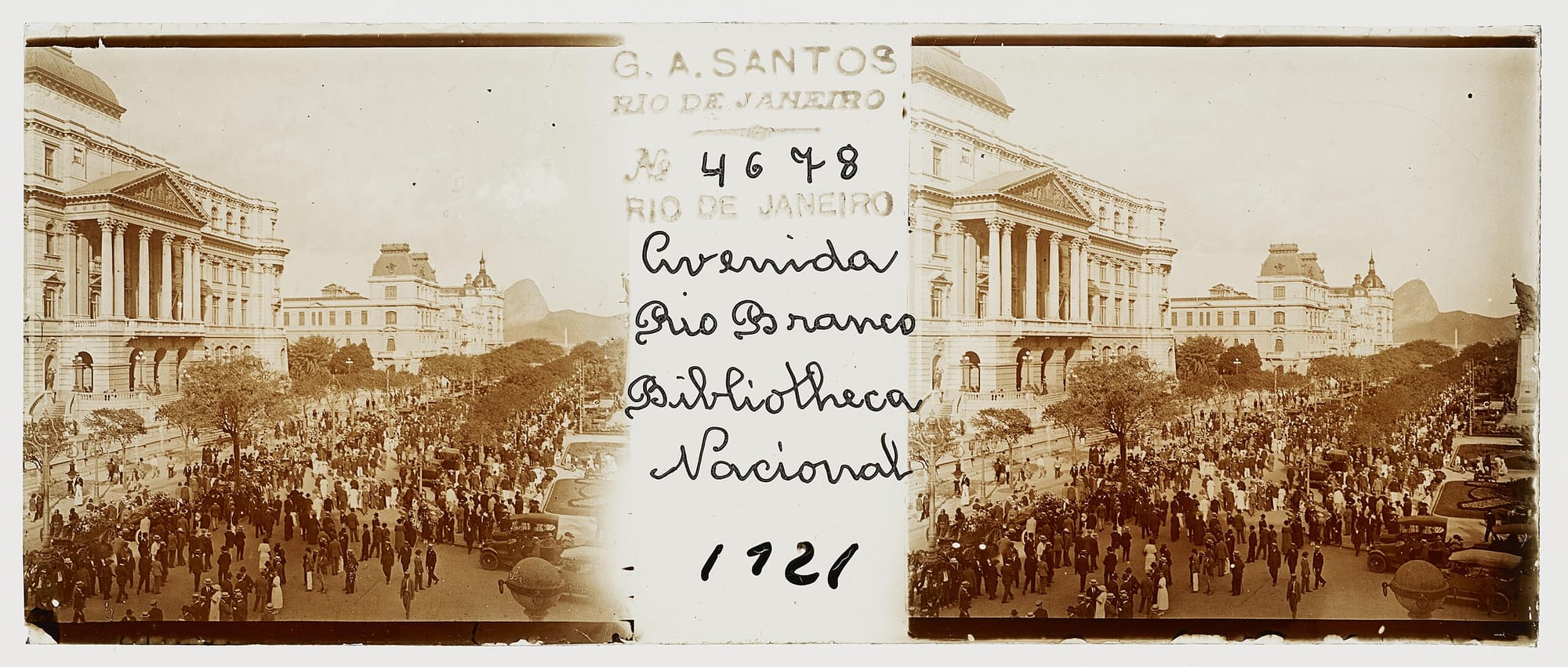

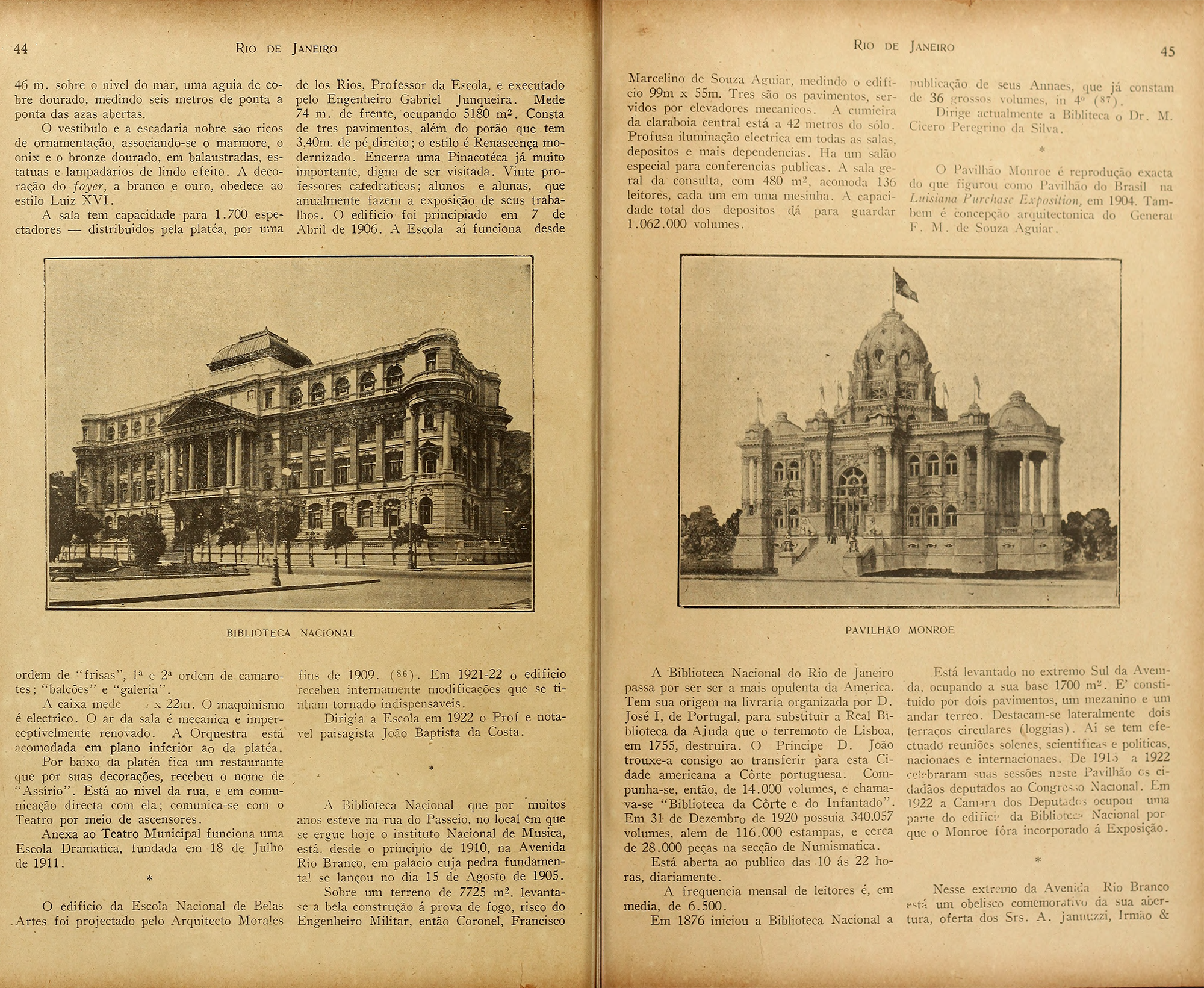

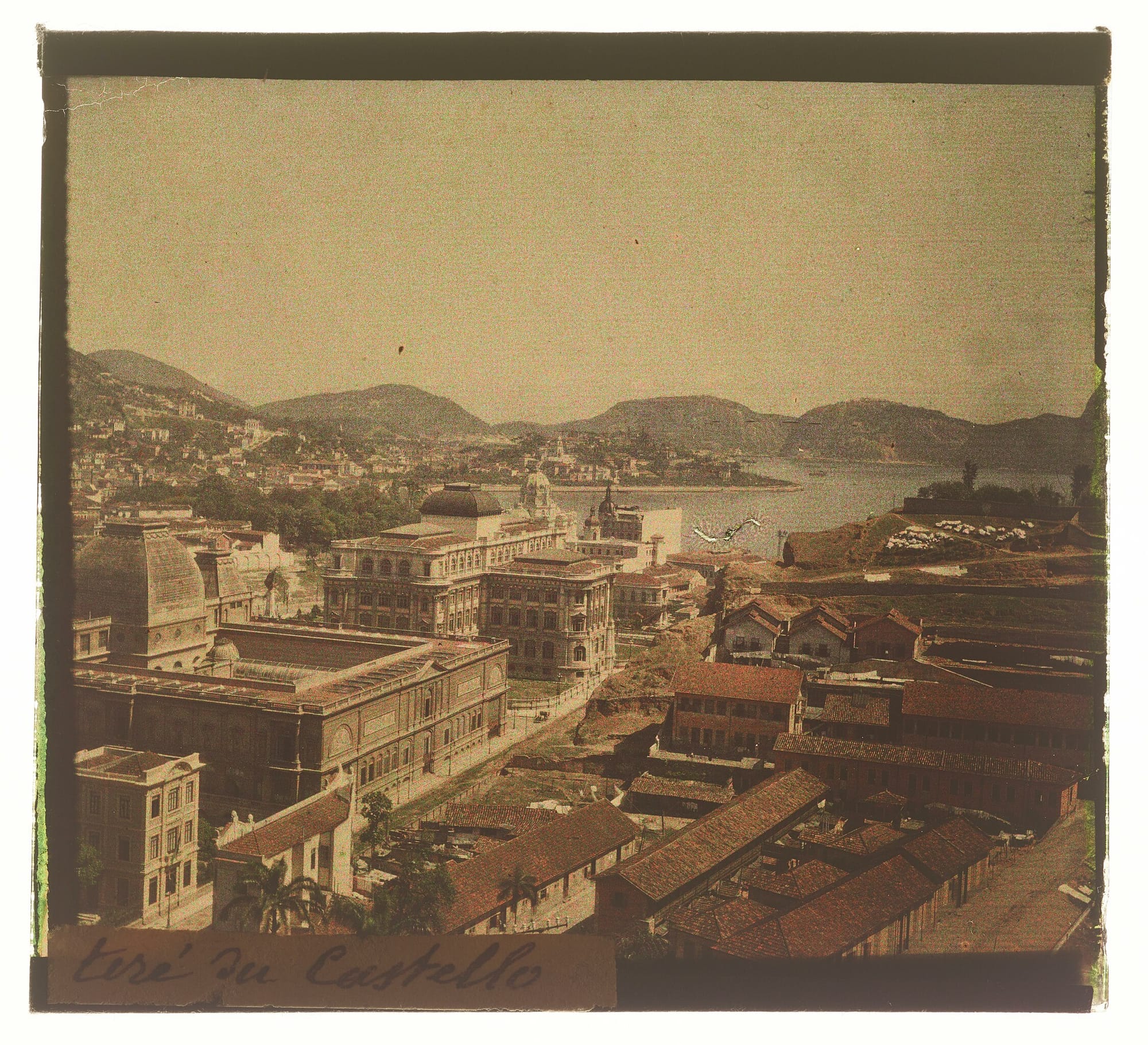

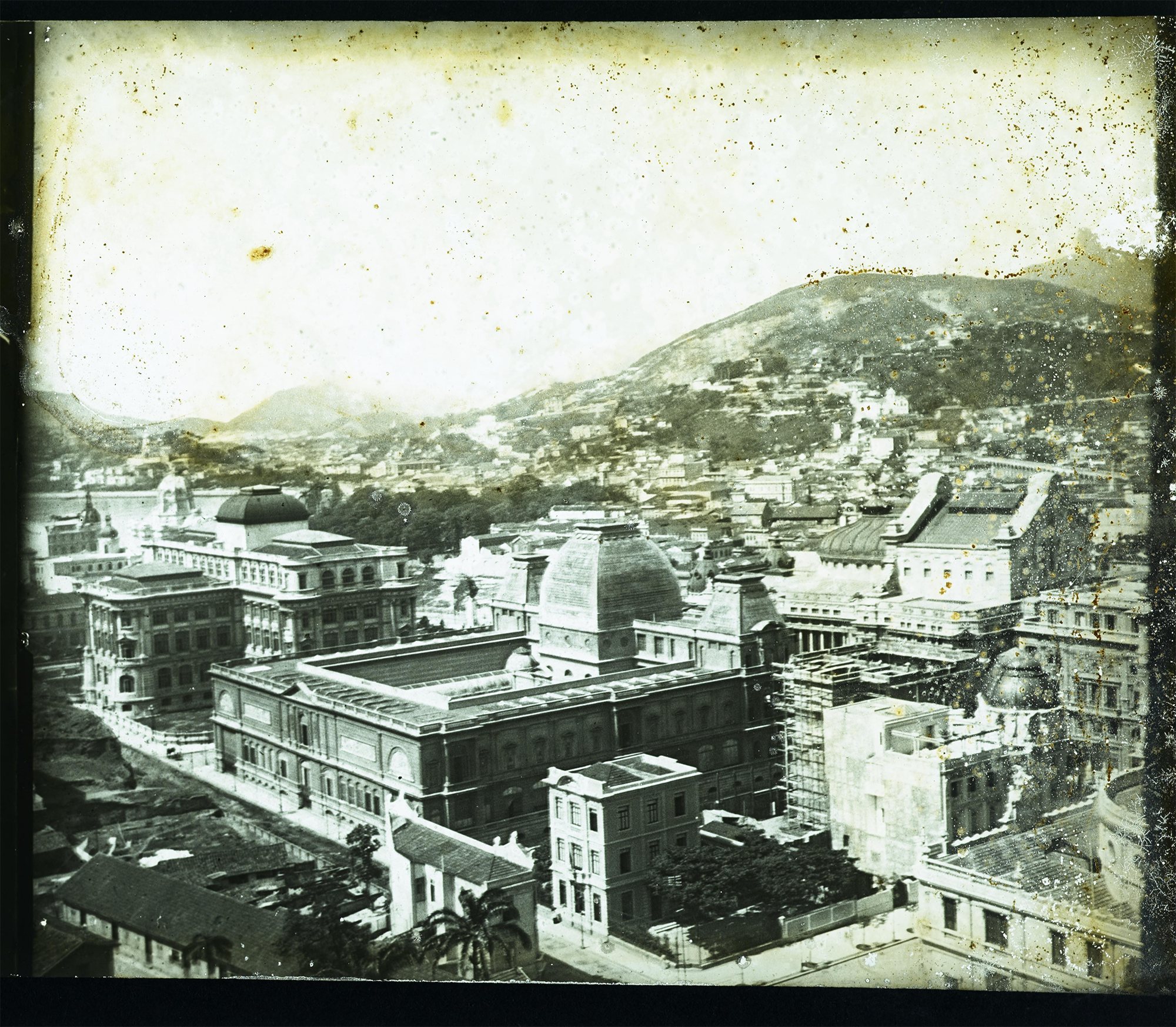

…Costa succeeded, temporarily, but it was Sousa Aguiar who designed the building, a massive neoclassical and Art Nouveau pile that opened in 1910. A Brazilian military engineer and architect, Sousa Aguiar also led the work on the Brazil Pavilions at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago and the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. The latter would be partially rebuilt in Rio as the Palácio Monroe, down the street from here. The Biblioteca Nacional, Theatro Municipal, and Palácio Monroe composed the opulent civic crown of the new Avenida Central, the Parisian-style boulevard carved through the city in 1904 during the O Bota-Abaixo, the knock-it-down era. While Brazil moved its capital out of Rio in 1960, the National Library stuck around—still here and appropriately grandiose for the largest library in South America.

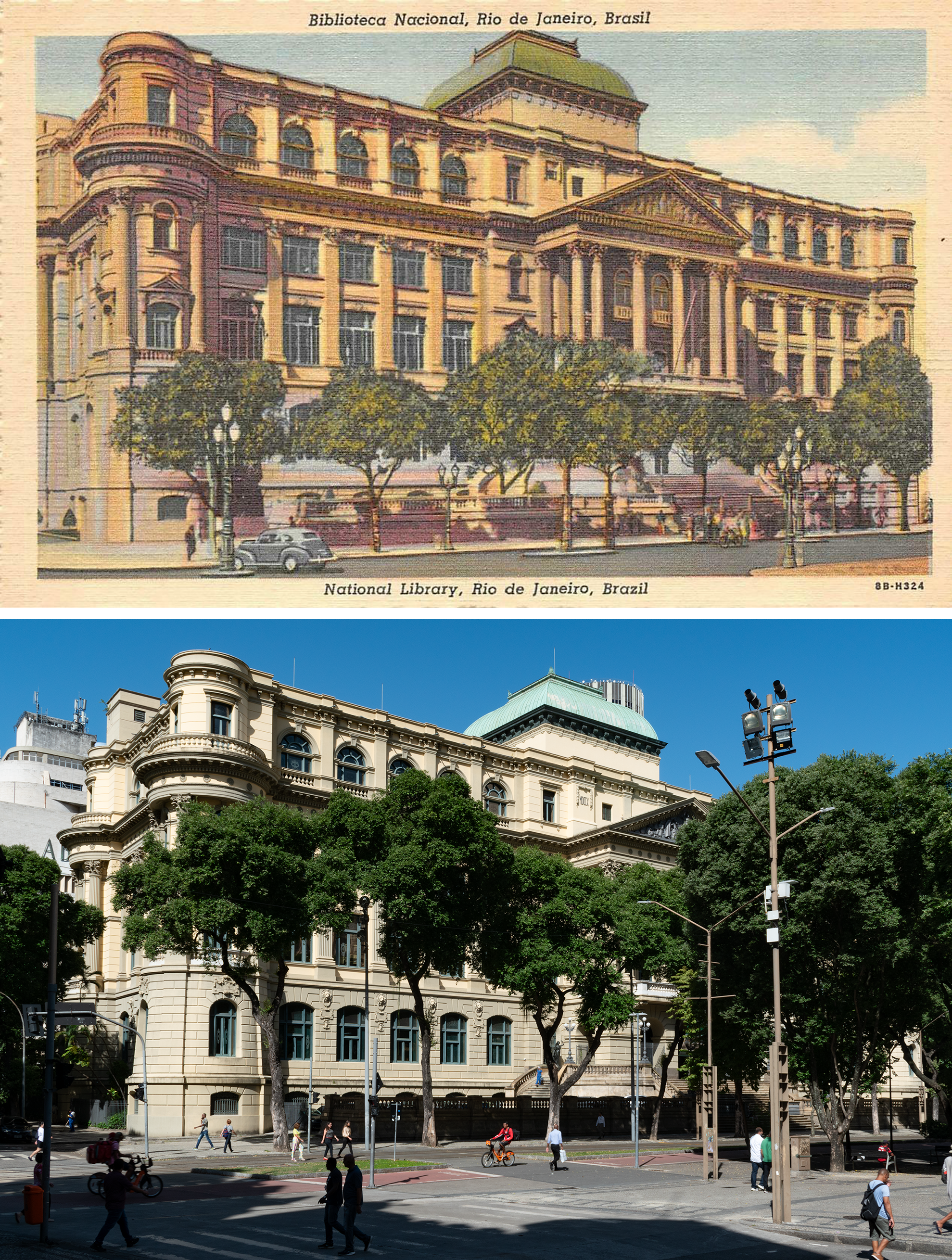

So, what’s changed? With the building a listed heritage monument, one that received a major restoration that wrapped up in 2018...not much.

- This is a rare one where the public transportation situation has improved. Spot the streetcar tracks? They're for the VLT Carioca, Rio’s light rail system that opened in 2016.

- Plus that red stripe of a nice and wide protected bike lane—so many pedestrians and no cars!

- Do we think those trees are the same ones in the postcard, just with 75+ years of growth? I lean yes.

The establishment of the National Library of Brazil dates back to the Napoleonic invasion of Portugal. When the Portuguese monarchy fled to their largest colony—Brazil—the contents of the Royal Library followed. The first batch of documents landed here in 1810, planting the seed of what would become the National Library of Brazil when the country declared and won its independence in the 1820s. The collection continued to expand throughout the 1800s, outgrowing its original building and a larger successor, so in the early 1900s the federal government tapped military engineer Francisco Marcelino de Sousa Aguiar to design a new home for the National Library.

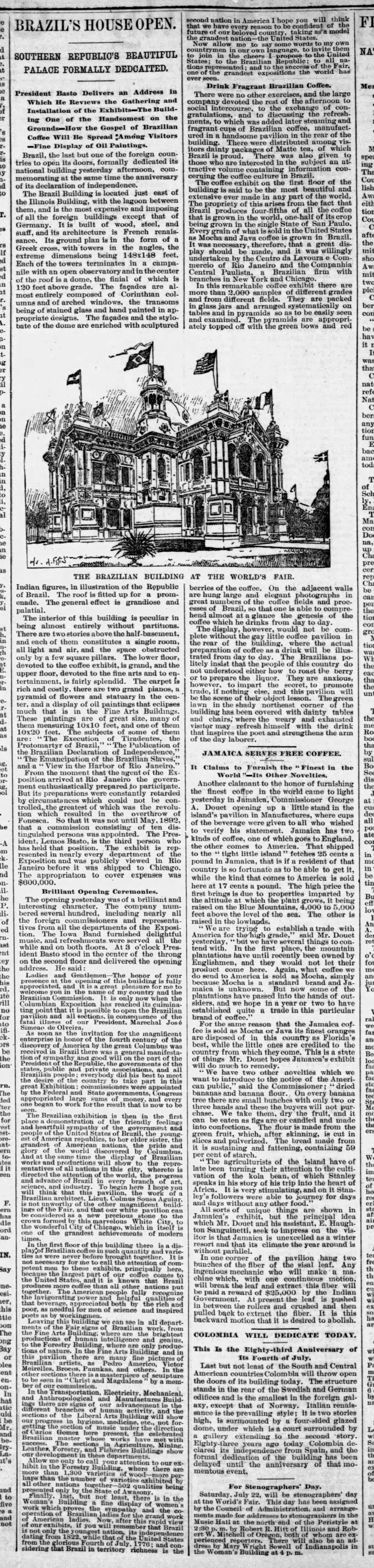

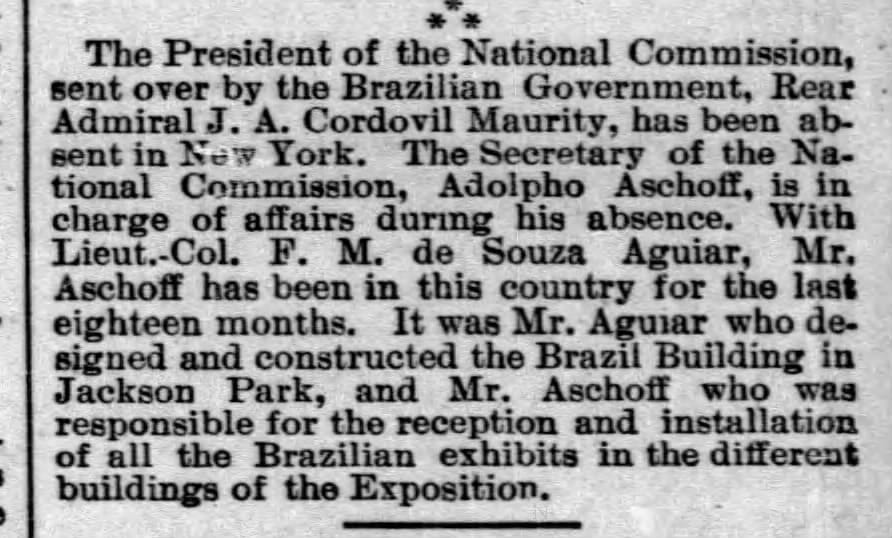

From what I can tell, Sousa Aguiar diligently advanced through the ranks of the Brazilian military as an engineer doing more-or-less normal engineer work until, in 1892, he was chosen to design the Brazil Pavilion at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Then a Lt. Colonel, Sousa Aguiar spent more than 18 months in Chicago for the World’s Fair working on the Brazil Building, a gaudy confection covered in little domes and Corinthian columns (reviews at the time were more positive than mine).

1893 articles about the Brazil Building at the World's Fair | 1893 photo, C.D. Arnold, Chicago Public Library via Chicago Collections

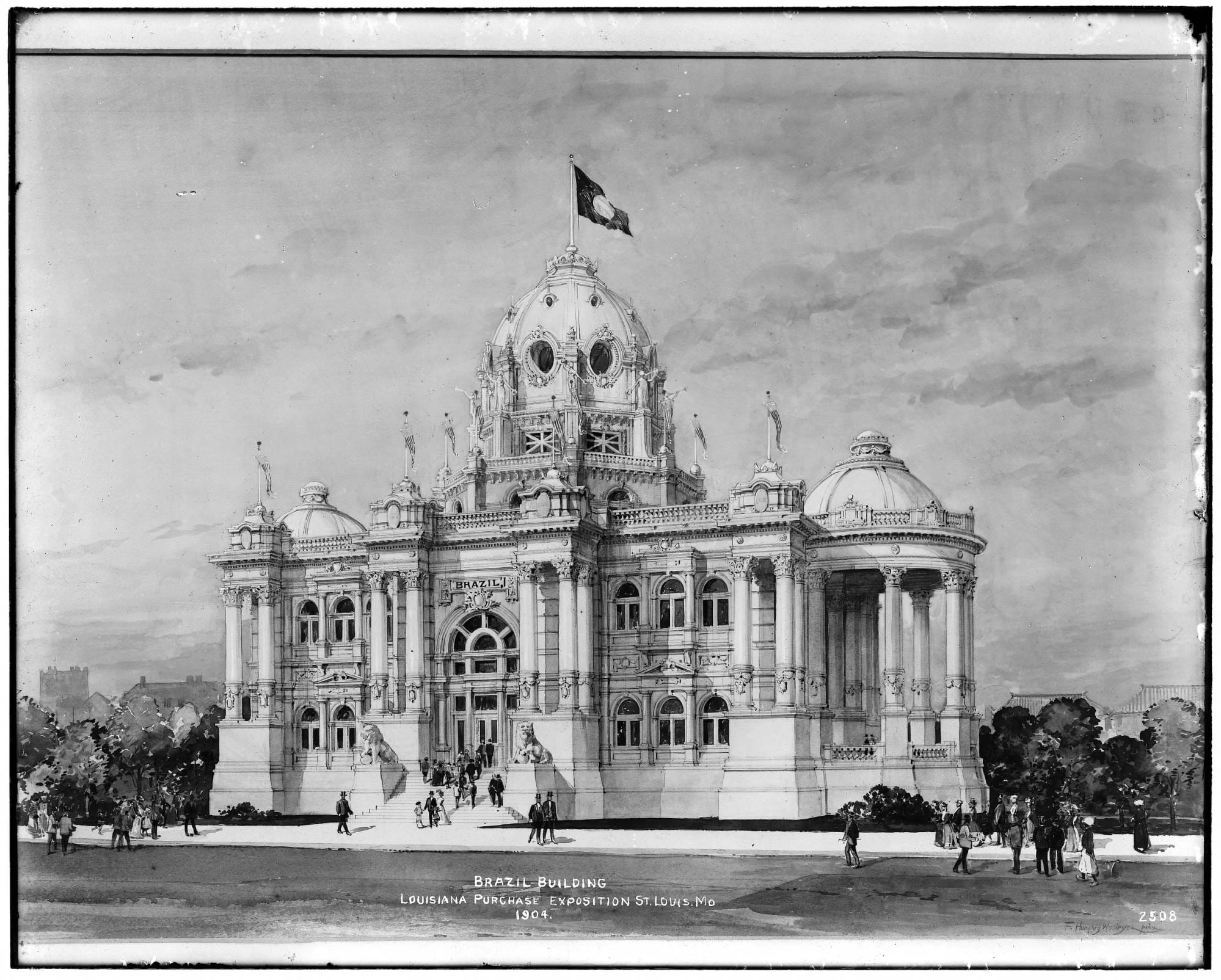

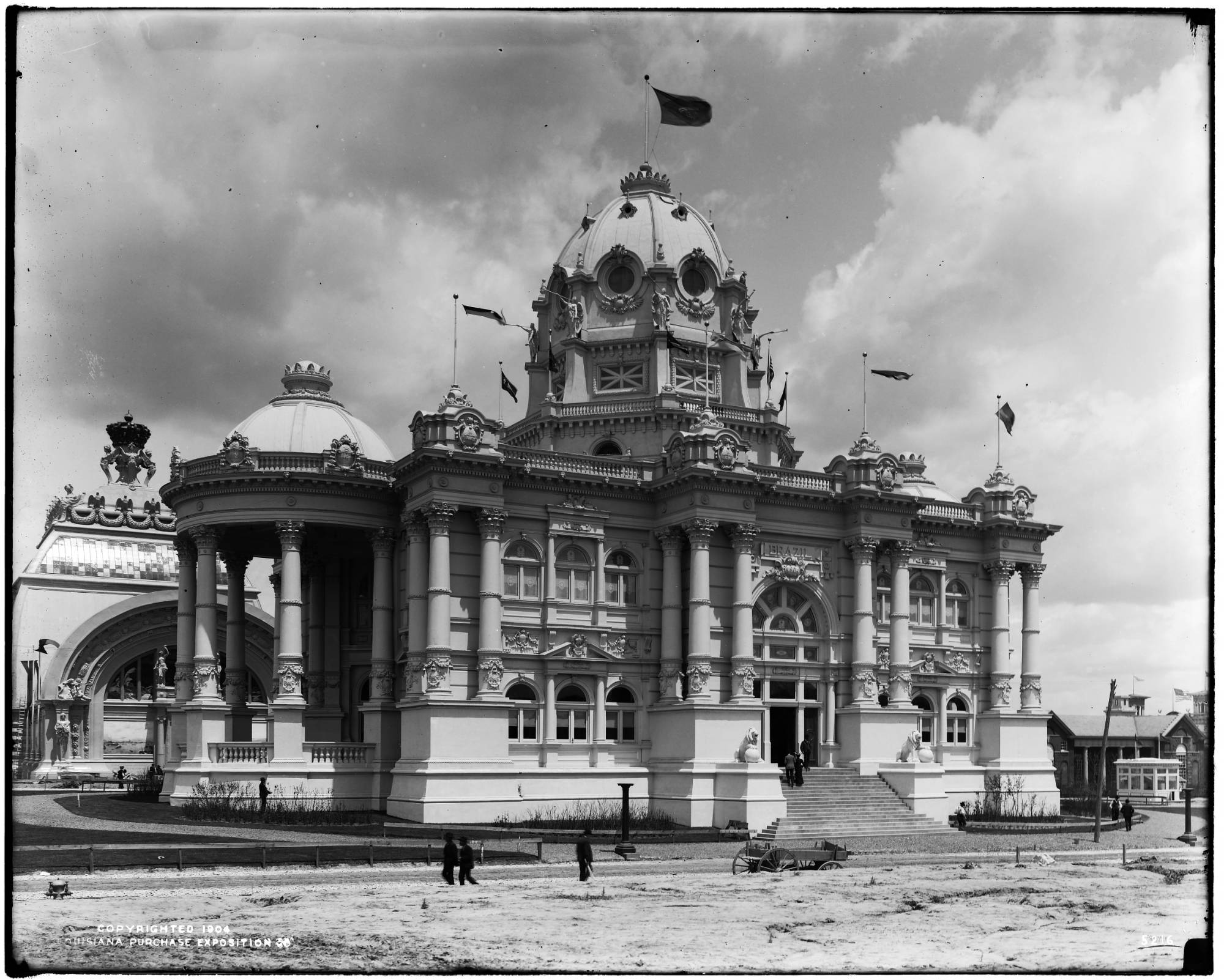

The Brazilians must have been happy enough with the reception of their Chicago pavilion, because they went back to Sousa Aguiar again to lead their participation in the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. This time with a twist, though—the Brazilian federal government wanted Sousa Aguiar to design a pavilion that could be disassembled, brought back, and rebuilt in Brazil (he’d partially succeed—the Palácio Monroe in Rio was a replica that reused the iron and glass dome from St. Louis).

Sousa Aguiar, Arquivo Nacional, Wikimedia Commons | 1903 rendering, St. Louis Public Library Digital Collections | 1904, St. Louis Public Library Digital Collections | 1904, St. Louis Public Library Digital Collections | Postcard, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons

Picked for the National Library commission while living in St. Louis, Sousa Aguiar actually did most of his work on the design there, with the cornerstone laid in 1905 after the World’s Fair in St. Louis ended. Fitting for a city in the midst of an urban renewal wave, Sousa Aguiar was appointed Mayor of Rio de Janeiro in 1906, while the library was under construction.

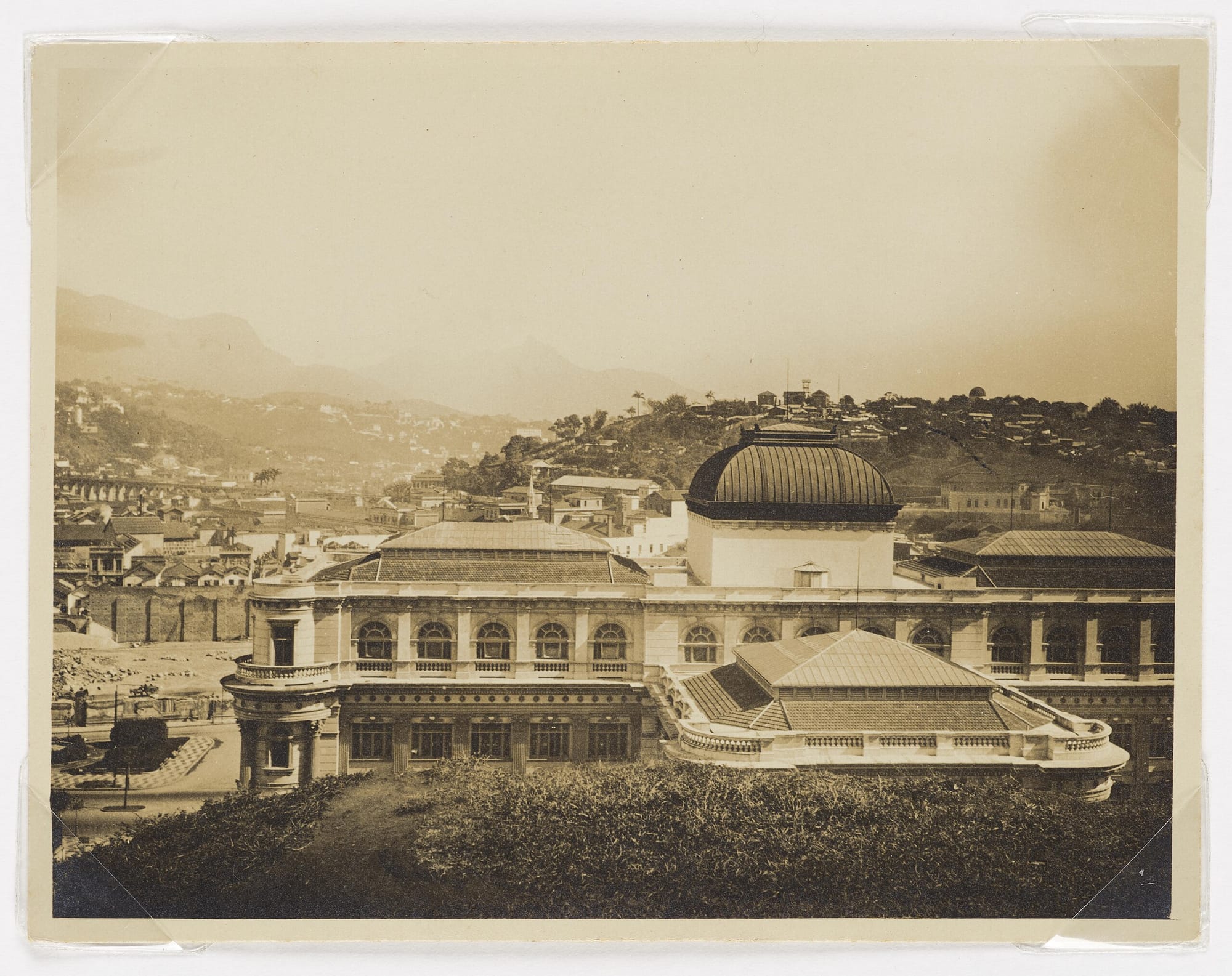

Dedicated in 1910, the National Library of Brazil contains a lot of the same design language as the expo pavilions—domes and Corinthian columns, Art Nouveau, French Renaissance, and neoclassicism all smashed together.

~1910, Marc Ferrez, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons | 1910, Marc Ferrez, Wikimedia Commons | 1910, F. Garcia, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons | 1910s, Augusto Malta, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons | 1910, Marc Ferrez, Instituto Moreira Salles, Wikimedia Commons | Postcard, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons | 1921, Guilherme Santos, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons | 1951, Arquivo Nacional do Brasil via Wikimedia Commons

…like, it seems pretty straightforward that this goofy eclecticism fits within the oeuvre of the guy who designed those pavilions, but Lucio Costa disagreed. Costa, an incredibly influential Brazilian modernist who led the all-star team behind the Ministry of Education & Health Building and designed the master plan for Brasília, loathed Brazilian architecture’s eclectic phase. He pushed for the demolition of Sousa Aguiar’s Palácio Monroe, a demolition that’s still a bit of a preservation sore spot in Rio, and when the National Historic and Artistic Heritage Institute (IPHAN) listed the National Library building in 1973, Costa worked to convince his former colleagues that the library building wasn’t really Sousa Aguiar’s work at all.

To be fair to Lucio Costa, he didn’t pull that idea entirely out of thin air. The National Library building stands on Praça Floriano Peixoto (popularly known as Cinelândia), the crown of the Avenida Central urban renewal project that punched a Parisian-style boulevard through old colonial Rio in a burst of Haussmannian urban renewal. To guarantee aesthetic coherence, buildings erected on the avenue like the Caixa de Amortização had their facades chosen through a facade design competition. With that in mind, Costa argued that Sousa Aguiar, acting more as a manager or a supervising architect, had actually acquired the facade design from a French architect, Hector Pepin. Costa’s arguments initially swayed IPHAN, and the building was attributed to Pepin when it was listed.

Costa’s theory relied on some very tenuous evidence and—aghast at one of their father’s most visible projects credited to someone else—one of Sousa Aguiar’s sons provided extensive primary source documentation that the National Library design was his work. IPHAN reversed its decision in the early 1980s and restored the attribution to Sousa Aguiar.

1924, the Internet Archive | 1930s, Augusto Malta, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons | 1910s, Marc Ferrez, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons | 1910s, Marc Ferrez, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons

Production Files

Further reading:

- Biblioteca Nacional: 200 anos de arquitetura

- The library's history in their own words

- Palácio Monroe: Da Glória Ao Opróbrio by Louis De Souza

- "A Palace of Books in the Tropics: Metaphor, Projects and Realizations" by Nelson Schapochnik

- "Construção diplomática, missão arquitetônica: os pavilhões do Brasil nas feiras internacionais de Saint Louis (1904) e Nova York (1939)" by Oígres Lêici Cordeiro de Macedo

- "O Patrimônio (Oficialmente) Rejeitado: A destruição do Palácio Monroe e suas repercussões no ambiente preservacionista carioca" by Fernando Atique

- É lançada a pedra fundamental do prédio da Biblioteca Nacional, na então Avenida Central, em 15 de agosto de 1905

- A saga do Palácio Monroe

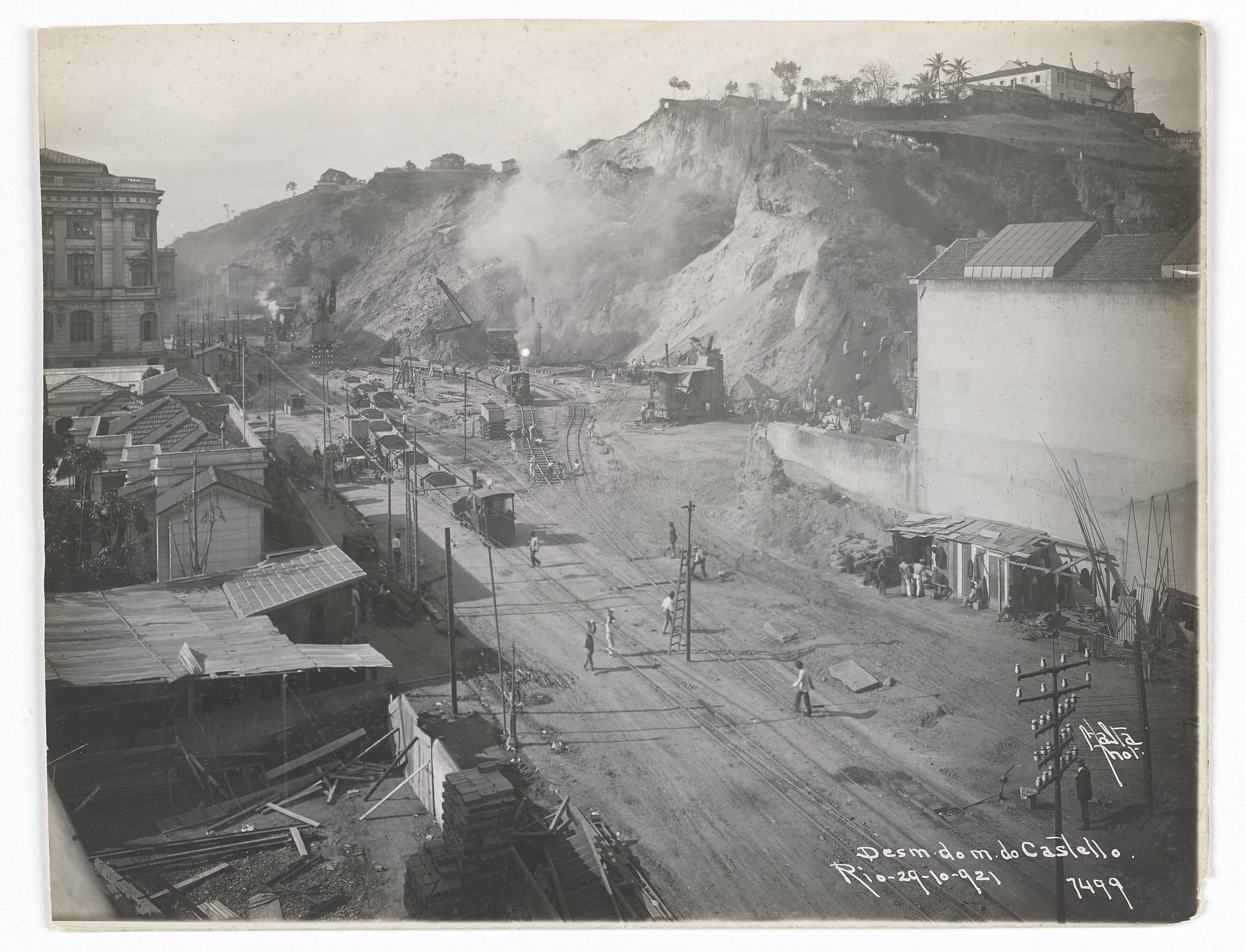

Thought it was interesting that there used to be a hill behind the library building, which was leveled in 1921.

1910s, Marc Ferrez, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons | 1910s, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons | Augusto Malta, 1921, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons

Member discussion: