The big bang of Brazilian modernism, the Gustavo Capanema Palace in Rio was the thrilling result of a productive, contentious, and short partnership between Le Corbusier and a Brazilian architectural all-star team composed of Lucio Costa, Affonso Eduardo Reidy, Oscar Niemeyer, and Roberto Burle Marx, among others. That said, it was actually Archimedes Memória who won the juried competition to design the offices of the new federal Ministry of Education and Health, but Capanema—a powerful bureaucrat in an authoritarian government, but one whose leader, Getúlio Vargas, had no real personal interest in cutting-edge design—paid Memória his prize money, told him to fuck off, and hired Lucio Costa anyway.

Completed in 1945, popular opposition foiled President Jair Bolsonaro’s attempt to sell the building in 2021, foreshadowing the Brazilian state thwarting Bolsonaro’s coup attempt in 2023 (and–because Brazil, unlike the US, is a functional country—imprisoning the coupmakers). The building reopened this year after a six year restoration effort led by IPHAN, the Brazilian National Historic and Artistic Heritage Institute.

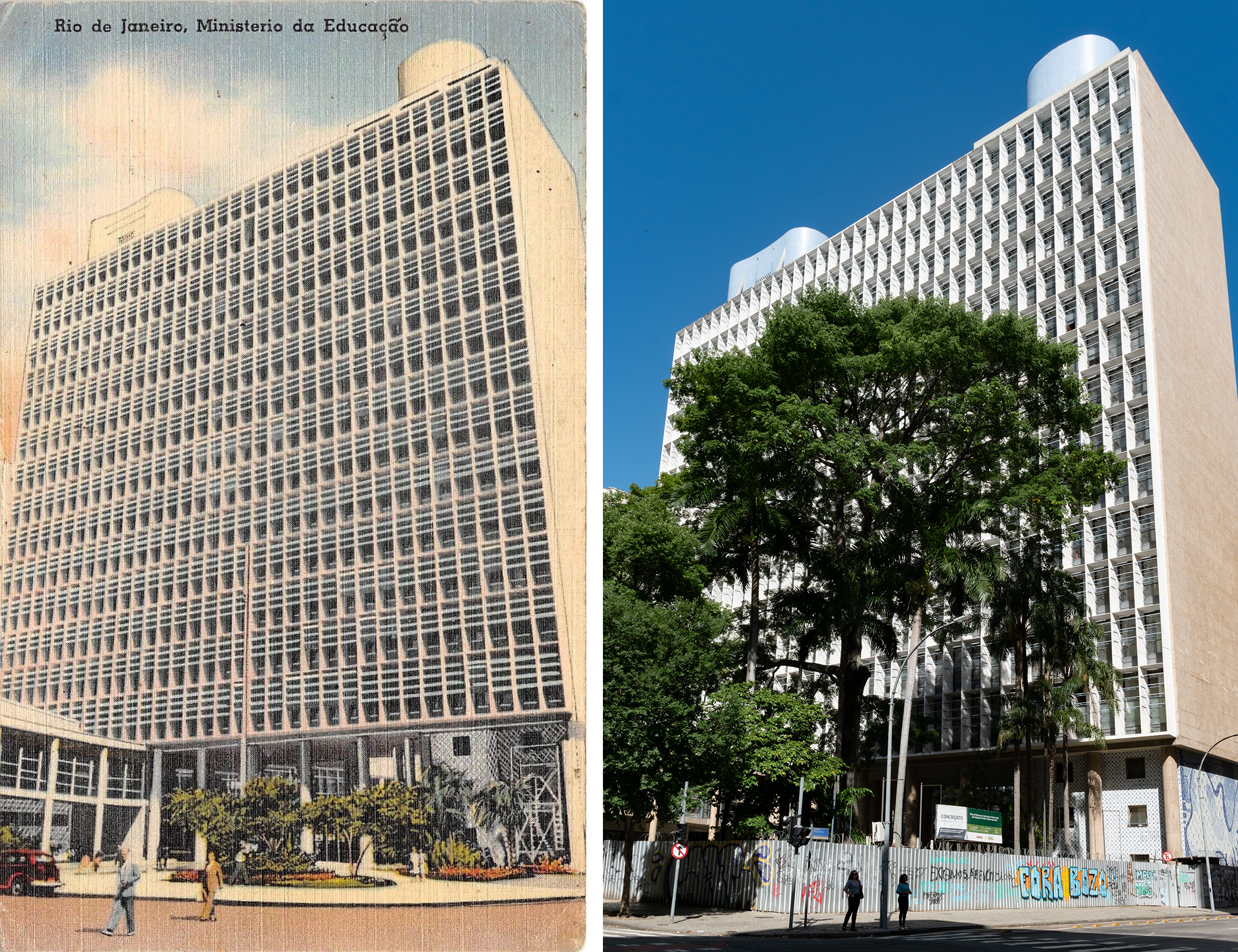

So, what’s changed? Incredibly, the Brazilian government listed the building on their national heritage register in 1948, only three short years after it officially opened, so, well…the trees grew in? I guess the specific government tenant here changed as the Brazilian federal state transformed—remember, the federal government upped stakes and left Rio for Brasilia in the 1960s—so the building housed the Ministry of Education & Health until 1953, then the Ministry of Education & Culture until 1985, and then Ministry of Culture from then on. Otherwise, though, not much at all has changed, and that was in 2023, before IPHAN’s restoration finished up.

In 1930, Getúlio Vargas lost a presidential election, took power in an armed revolution, and—a ways down the list of major developments of that tumultuous year—established Brazil’s Ministry of Education & Health. The construction of the Ministry of Education & Health Building is inseparable from the rise of Vargas’s idiosyncratic regime, which combined Brazilian nationalism, statist economic policies, and proto-fascism performance of “national cultural renewal”.

President Vargas named education reformer Gustavo Capanema Minister of Education and Health in 1934. The ministry soon organized a juried competition to design their new headquarters, receiving 34 entries. Of those 34, only three were accepted, with the vast majority of the others immediately disqualified for not meeting the requirements (including an entry by Lucio Costa). The jury chose a monumental, vaguely fascist Art Deco proposal from Archimedes Memória inspired by Marajoara culture. Entries by Rafael Galvão and Mário Fertin and Gérson Pompeu Pinheiro came in second and third, respectively.

By most accounts, Getúlio Vargas had little interest in cultural policy or design. Minister Capanema did though, and he thought Memória’s plan was a monstrosity, so he paid Memória the prize money, discarded his plan, and hired Lucio Costa to design something modern. Memória, angrily wrote Vargas, lobbying him to overrule Capanema and calling the modernists communists, but remember—cultural policy wasn’t really Vargas’ thing.

Costa assembled a team that included architects Affonso Eduardo Reidy, Ernani Vasconcellos, Carlos Leão, Jorge Machado Moreira, and Oscar Niemeyer, along with structural engineer Emilio Baumgart and landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx. Design work began in 1935, but with the design team dissatisfied with initial results, they invited famous Swiss modernist Le Corbusier to Rio to consult on the project.

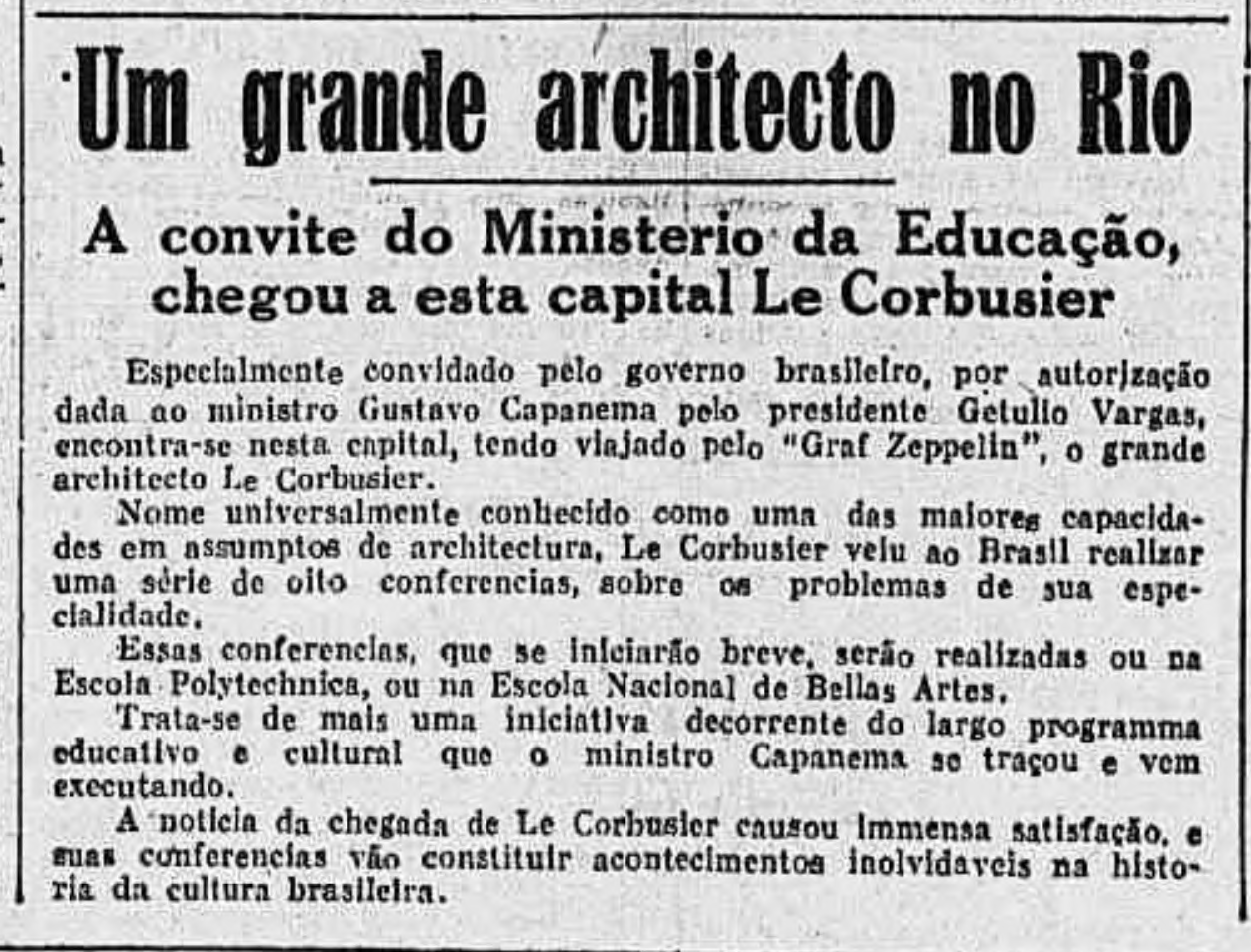

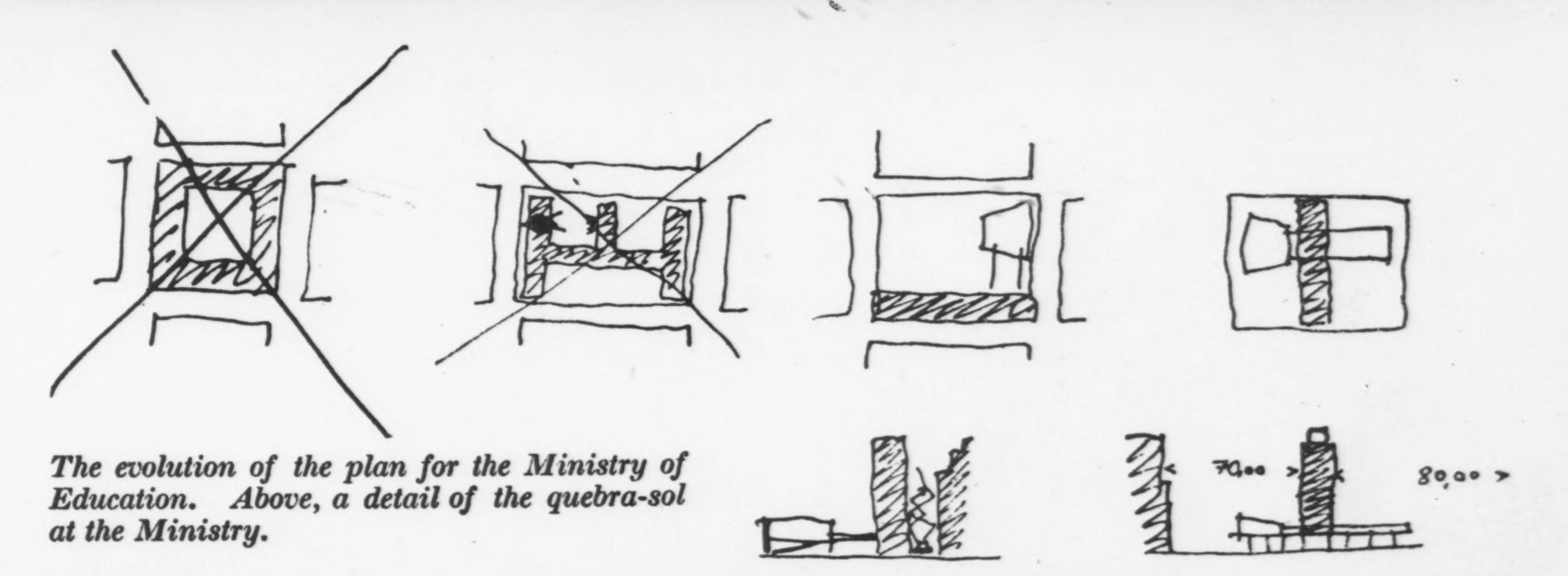

Le Corbusier visited Rio in 1936 for a short but incredibly influential visit. He ran roughshod over the project brief—pushing to move the building to a waterfront site the government didn’t own, among other things—but the back-and-forth between the young Brazilian modernists and the venerable European modernist galvanized the creative process, with Niemeyer crediting Le Corbusier’s presence with giving Brazilian group the “liberty and the creative force it needed”.

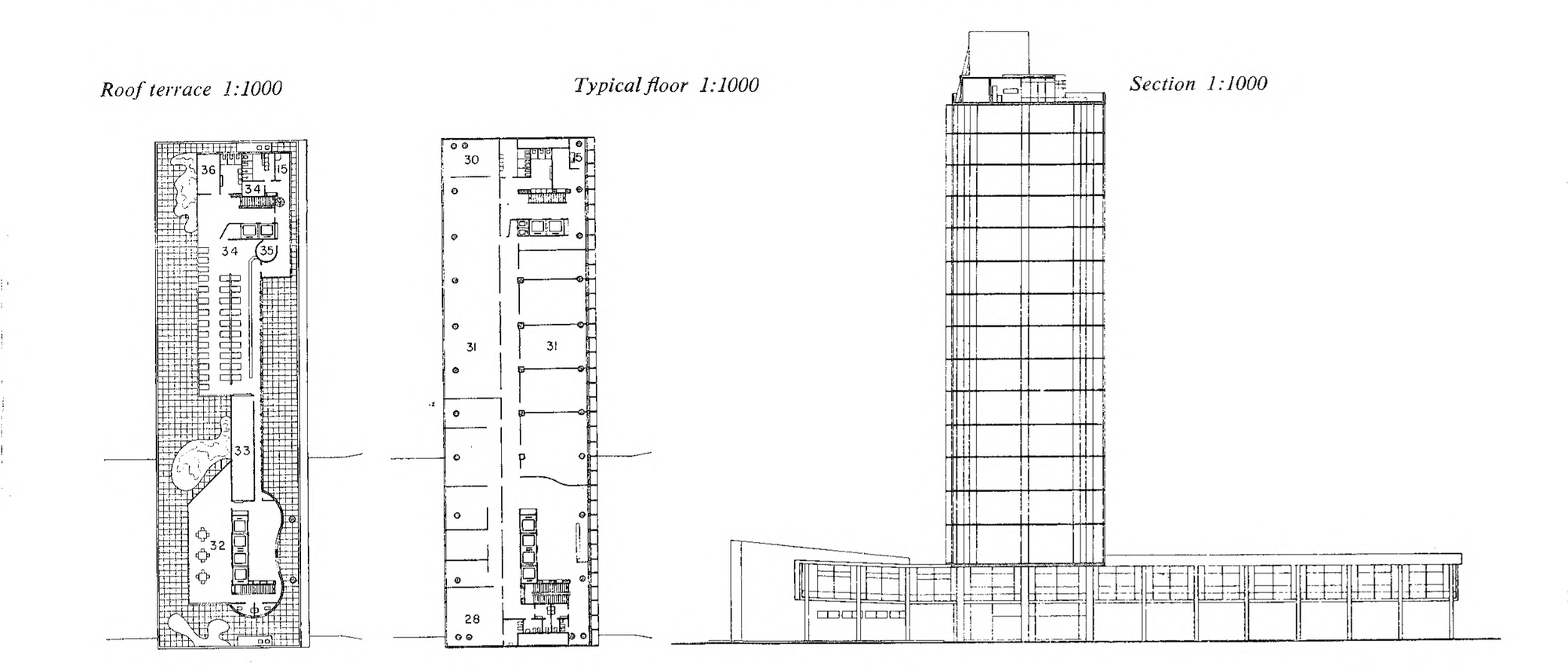

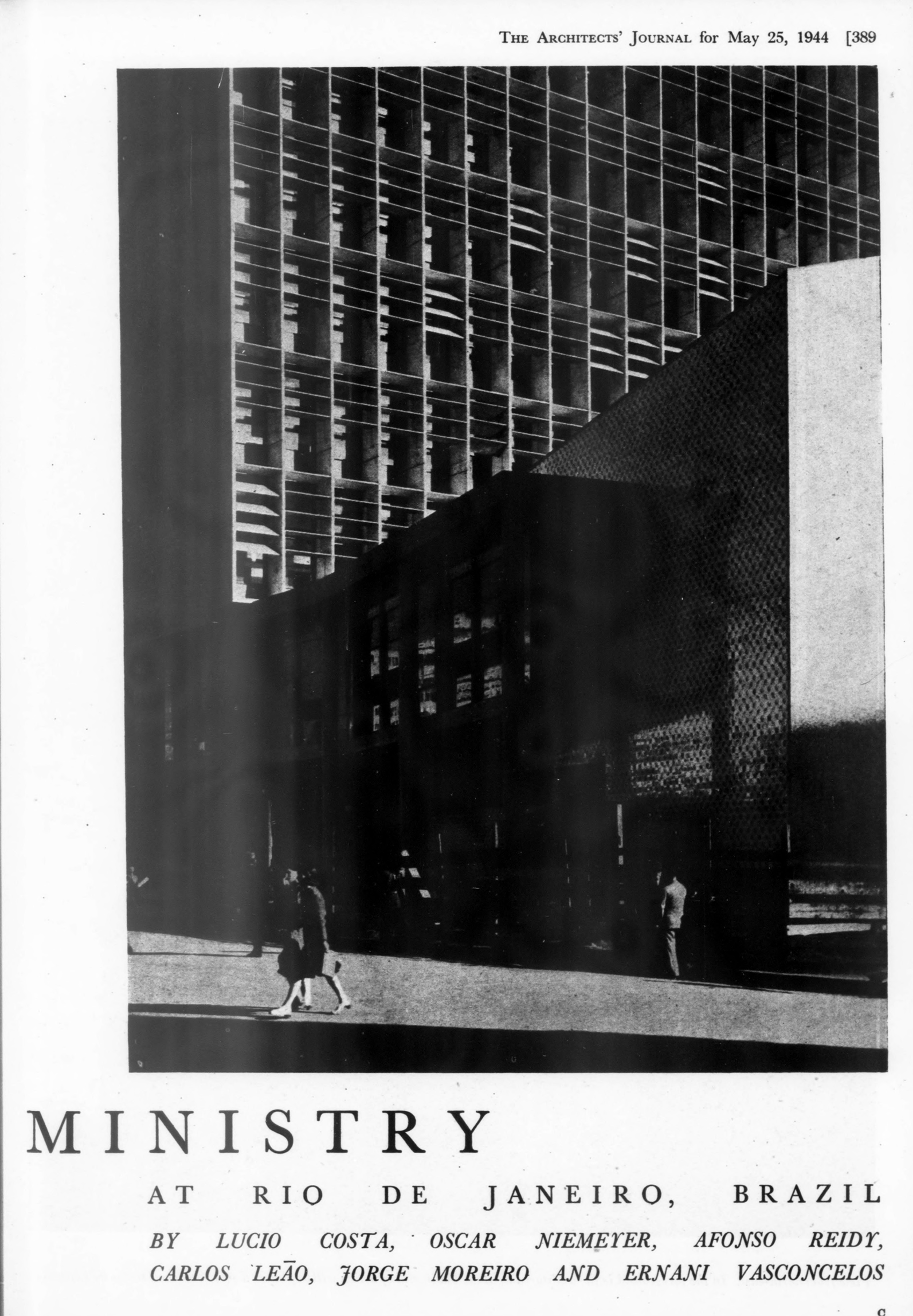

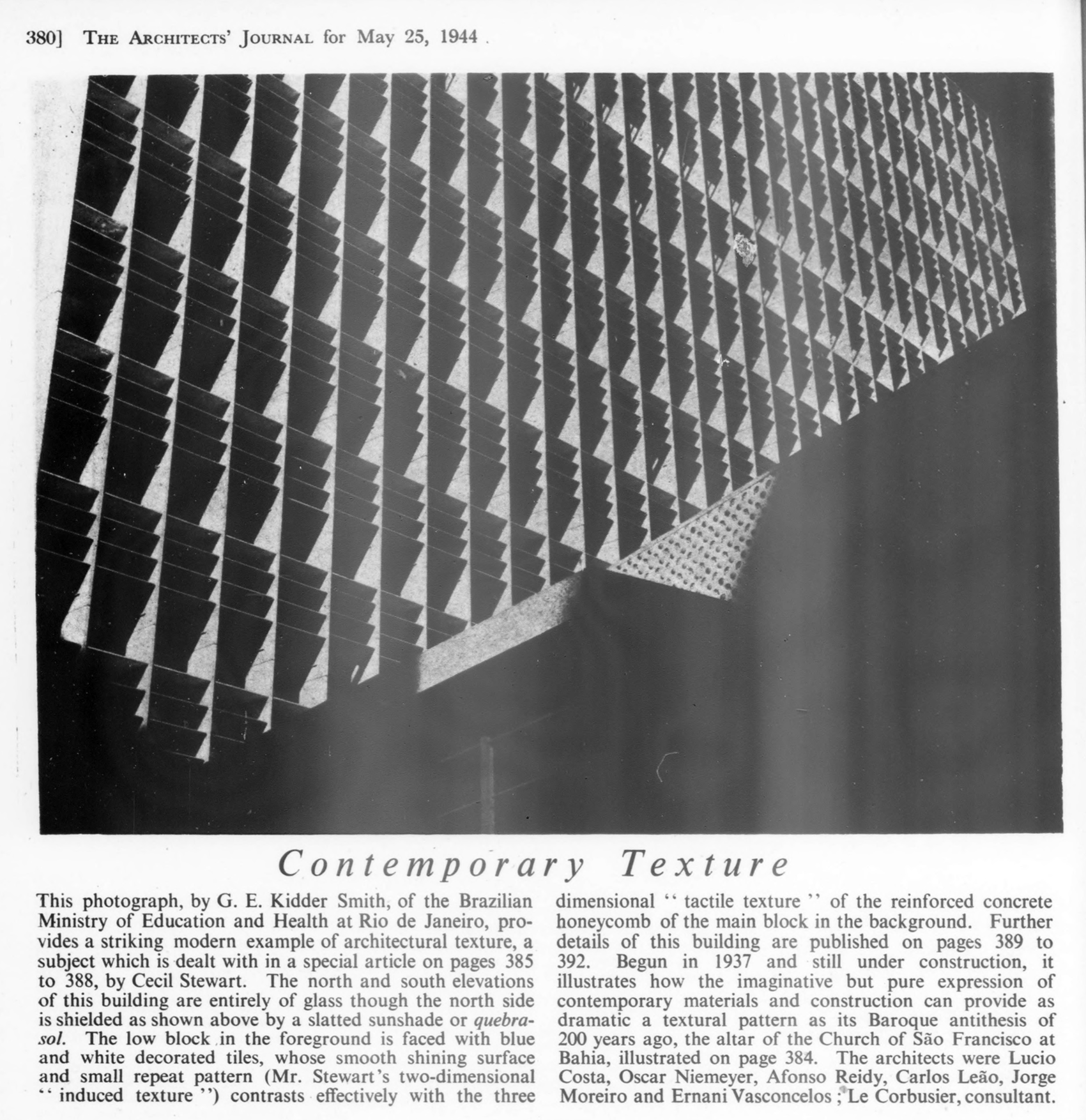

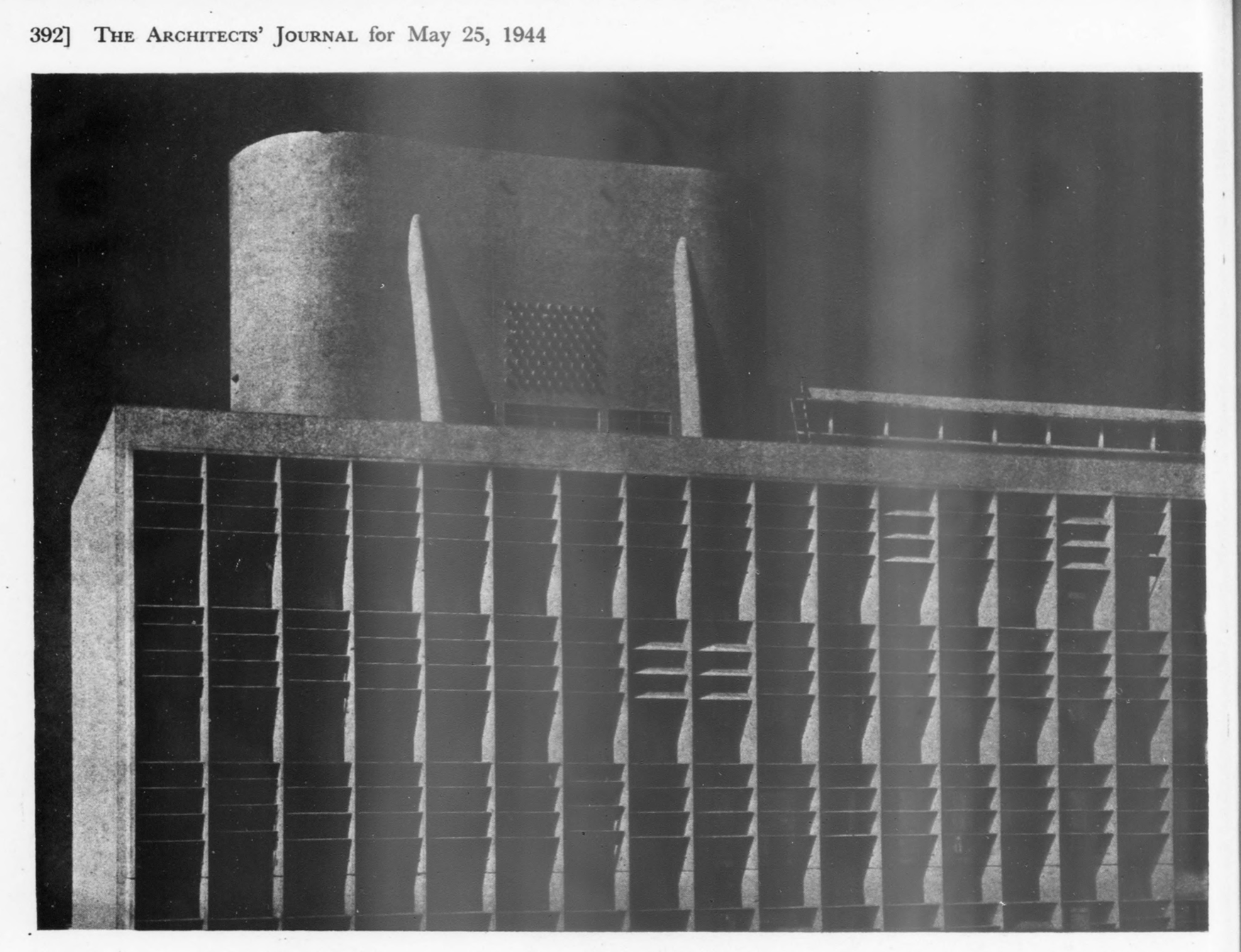

1936 O Jornal article, "Big Architect to Rio", the Internet Archive | 1937, cornerstone laying, the Internet Archive | Diagrams and sketches, 1944, The Architectural Review, the Internet Archive | 1944, "Brazil Outstrips US in Modern Architecture" | 1943, finishing up, A Noite, the Internet Archive | 1945, Inaugurated, the Internet Archive | 1944, the Architects' Journal, the Internet Archive

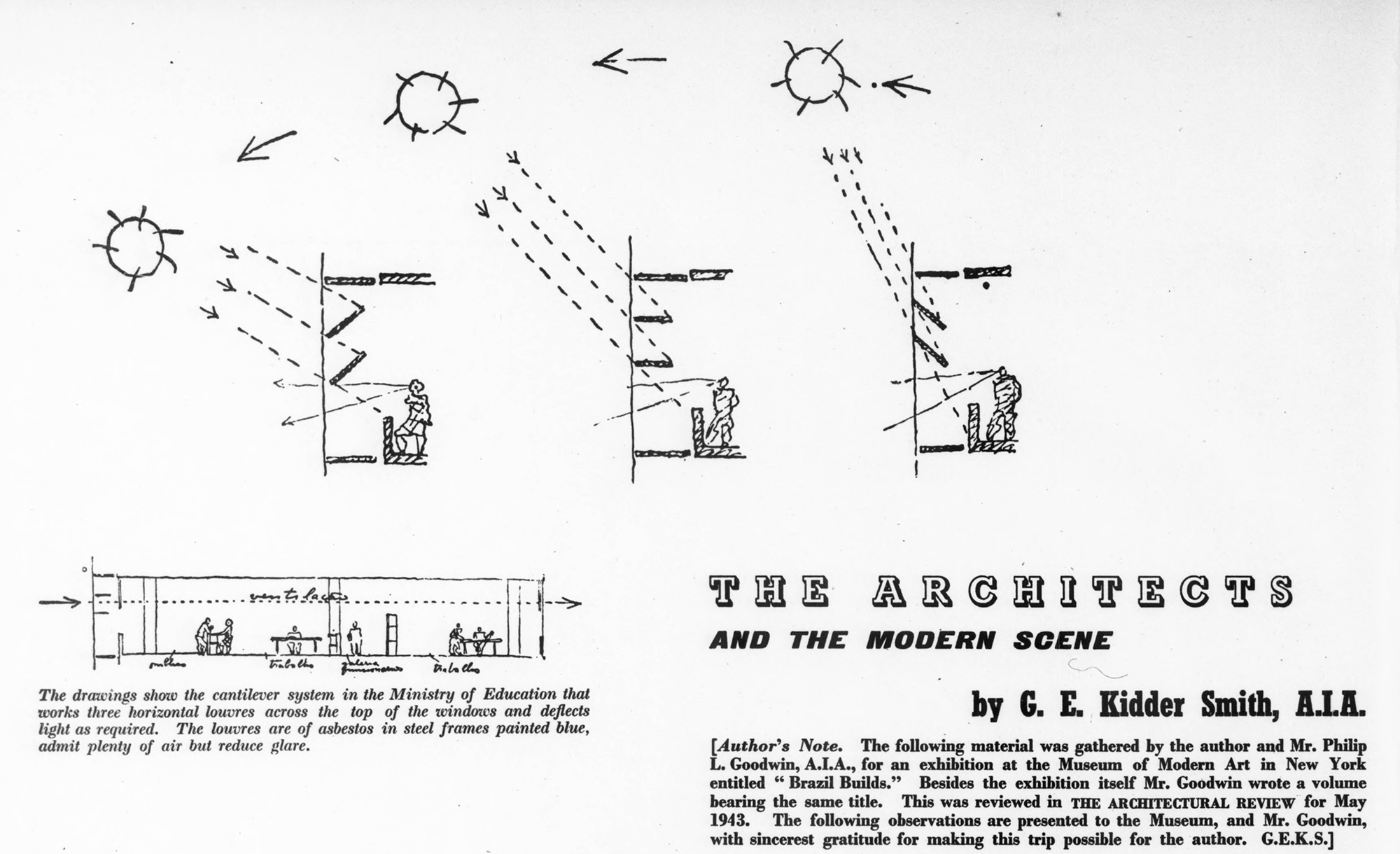

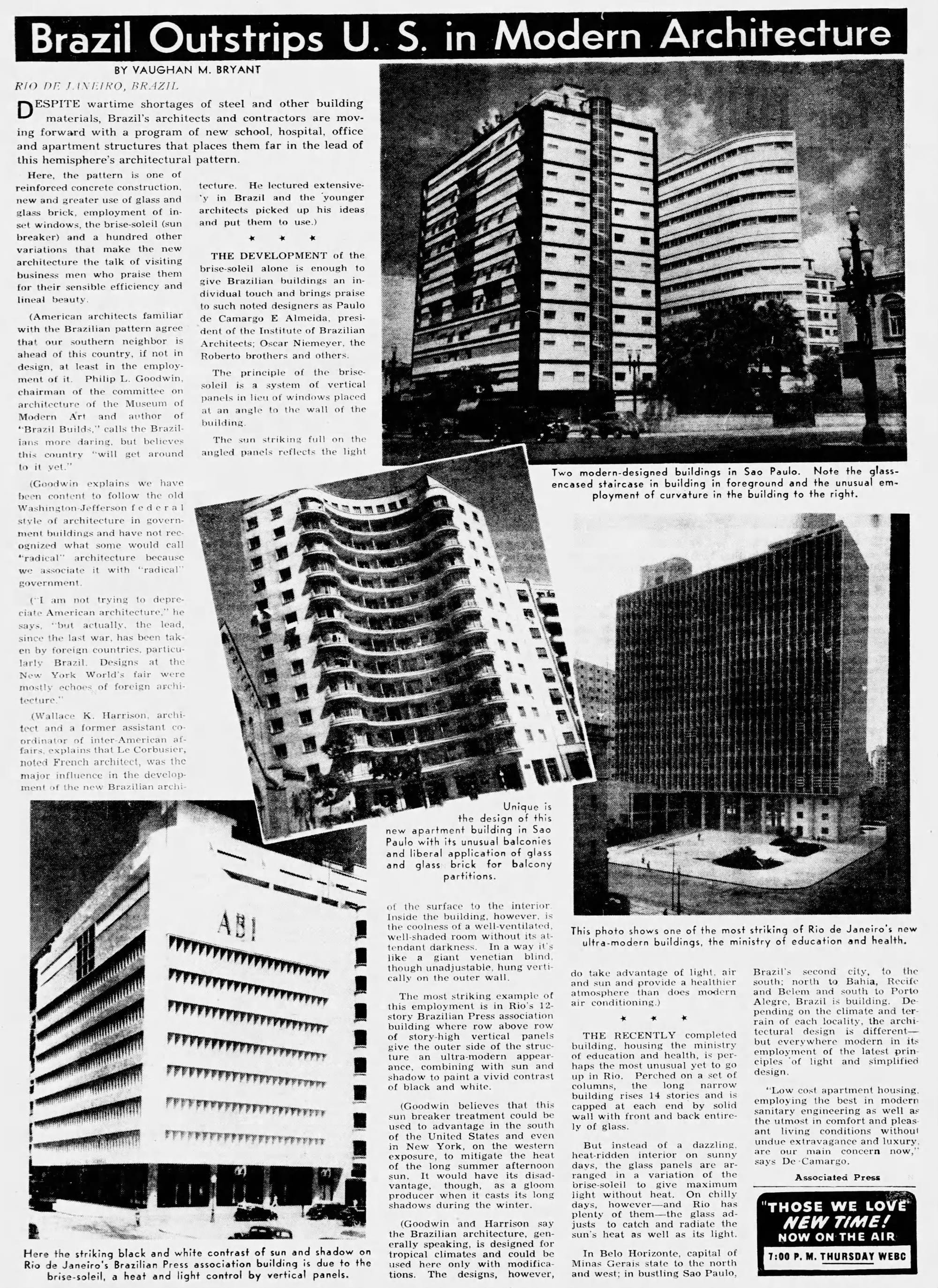

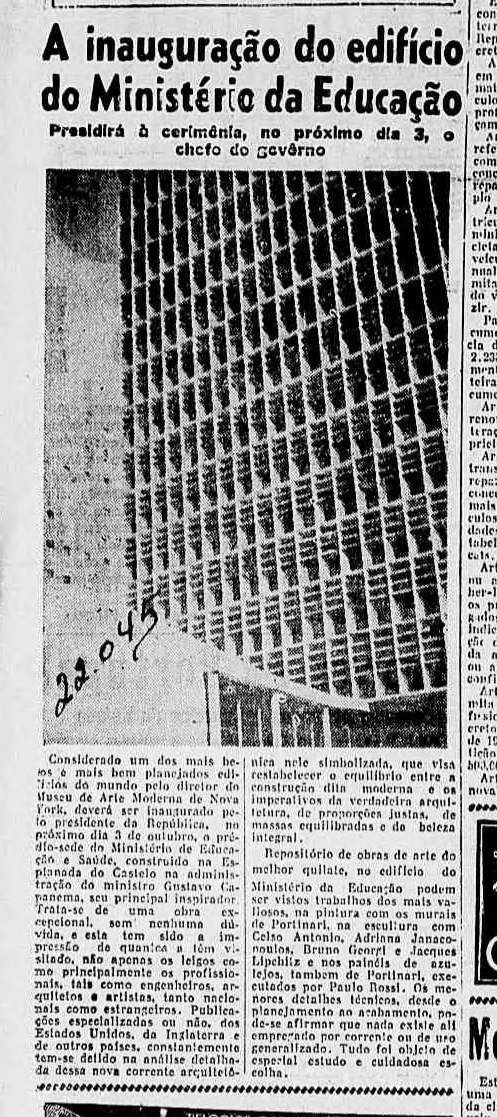

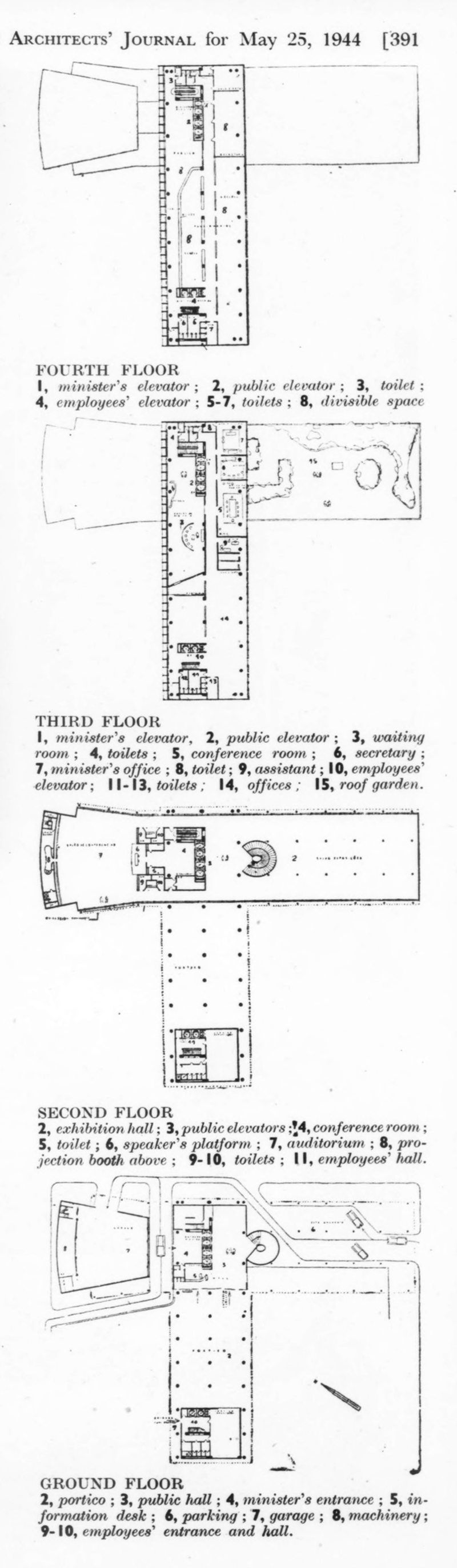

Construction began in 1937, and the building was an icon even before it opened—its inclusion in the Brazil Builds exhibition at MoMA in 1943 had Americans asking whether they’d fallen behind. A slab with a curtain wall, shaded by a brises-soleil, standing on pilotis, and decorated with azulejos—an incredible synthesis of Corbusian and Brazilian modernism, really, like a supergroup coalescing to create a single flawless album that defines an entire genre. The end result also embodies Le Corbusier's five points of architecture: pilotis, a free ground-plan, a free façade, horizontal windows, and roof gardens (here, accentuated by those delightfully nautical blue tanks on top).

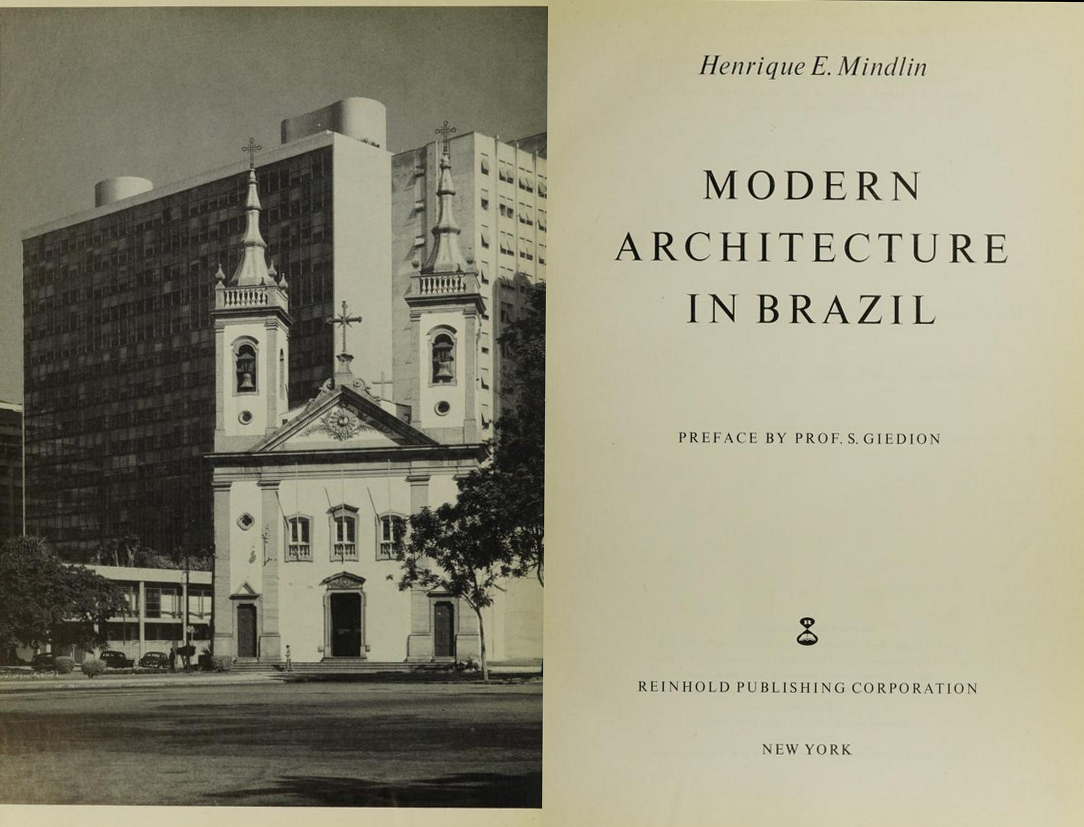

In the Architects' Journal, 1944, the Internet Archive | On the cover of Modern Architecture in Brazil, 1956 | 1953 photos from the Leonard Currie Slide Collection, Virginia Tech Libraries

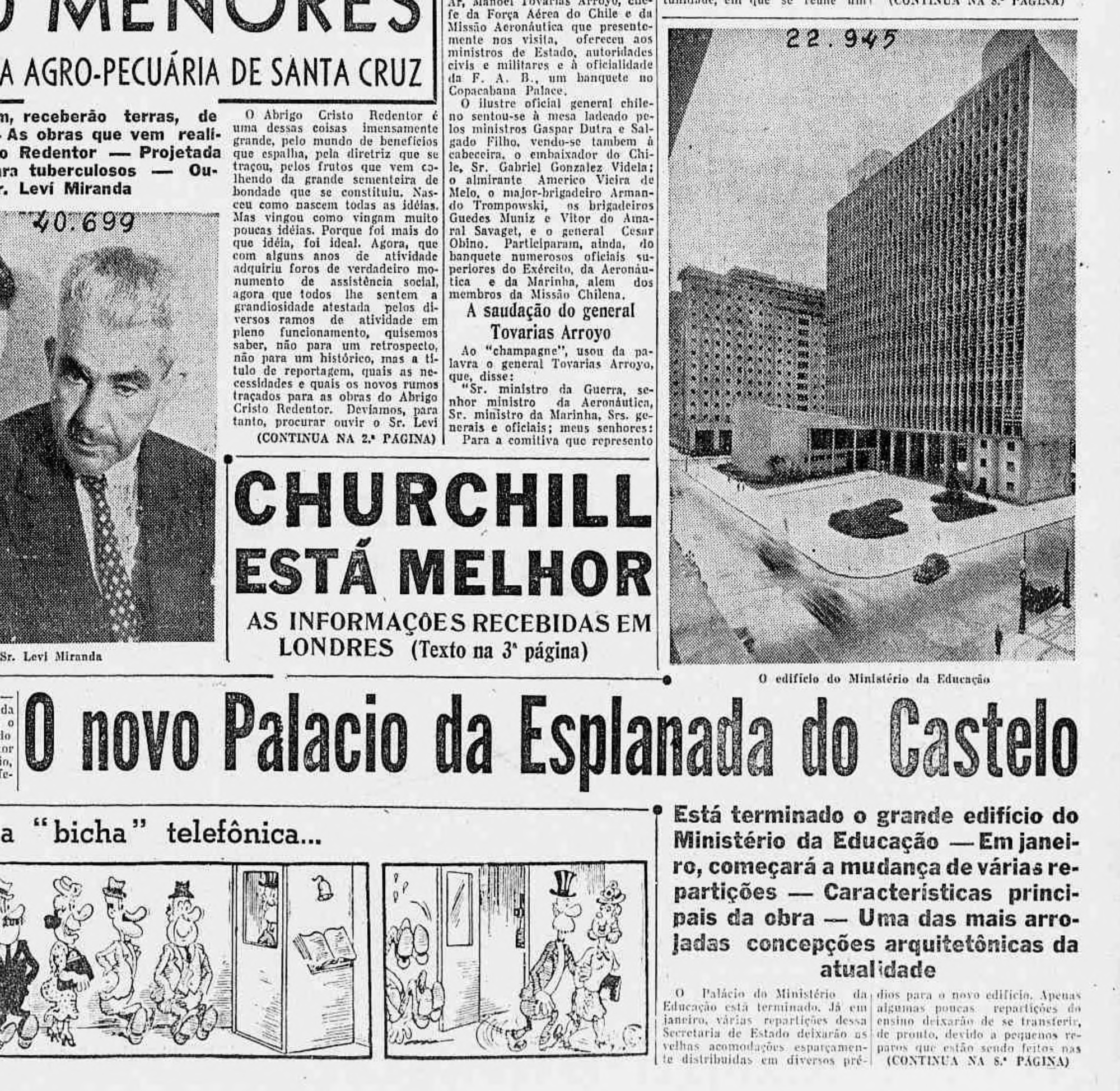

The Ministry moved into the building in 1944, it was officially inaugurated a year later, and by 1948 the Brazilian government had listed it on its cultural heritage register.

The design’s smashing immediate success soon had the architects fighting over who deserved the most credit, turning into a serious point of contention between Le Corbusier, Costa, and the young Brazilian team. It's a point people smarter than me (and with better Portuguese) are far more qualified to assess, but to me you can see a lot of Niemeyer, a lot of Le Corbusier, Costa deserves credit for orchestrating what must have been an absurdly precocious bunch, and Burle Marx’s landscape architecture makes the whole thing. There was also likely an element of professional frustration for Le Corbusier: how did a bunch of young upstarts in Brazil build a Corbusian tower before Le Corbusier himself could build one in Europe?

(...well, for one thing, it helps immensely to have a powerful bureaucrat as a patron [as well as an uninterested dictator])

Antônio Luiz Dias de Andrade, Collection Centro de Memória - Unicamp (CMU), Wikimedia Commons | Antônio Luiz Dias de Andrade, Collection Centro de Memória - Unicamp (CMU), Wikimedia Commons | Antônio Luiz Dias de Andrade, Collection Centro de Memória - Unicamp (CMU), Wikimedia Commons | Antônio Luiz Dias de Andrade, Collection Centro de Memória - Unicamp (CMU), Wikimedia Commons | Antônio Luiz Dias de Andrade, Collection Centro de Memória - Unicamp (CMU), Wikimedia Commons | Antônio Luiz Dias de Andrade, Collection Centro de Memória - Unicamp (CMU), Wikimedia Commons | 2012, Henrique Liberal, Wikimedia Commons | 2014, Henrique Liberal, Wikimedia Commons | 2014, Henrique Liberal, Wikimedia Commons

Production Files

Further reading:

- A sede do Ministério da Educação e Saúde. Ícone urbano da modernidade brasileira 1935–1945 by Roberto Segre

- Entre o concreto e o papel : a memória arquitetônica do Palácio Gustavo Capanema by Francesca Dalmagro Martinelli

- Colunas da educação: a construção do Ministério da Educação e Saúde, 1935-1945 edited by Mauricio Lissovsky and Paulo Sérgio Moraes de Sá

- "The Many Faces of a Para-Fascist Culture: Architecture, Politics and Power in Vargas’ Regime (1930–1945)" by Francisco Sales Trajano Filho

- "Predators and Cannibals: The Ministry of Education and Health in Rio de Janeiro" by Annette Spiro, translated by Thomas Skelton-Robinson

- "Cannibalizing Le Corbusier: The MES Gardens of Roberto Burle Marx" by Valerie Fraser

- Gerson Pompeu Pinheiro e a recepção dos ideais modernos na década de 1930 by Maristela Siolari

- "Vargas Era and the Politics of Cultural Production, 1930–1945" by Daryle Williams

- Série “Os arquitetos do Rio de Janeiro” IV – Archimedes Memória (1893 – 1960), o último dos ecléticos

A few more photos and articles I didn't have room for up there.

Engineering Masterpiece, 1942, the Internet Archive | 1953, Leonard Currie Slide Collection, Virginia Tech | Floor plans, 1944, the Architects' Journal | Antônio Luiz Dias de Andrade, Centro de Memória - Unicamp, Wikimedia Commons | 2004, Marcos Leite Almeida, Wikimedia Commons

Member discussion: