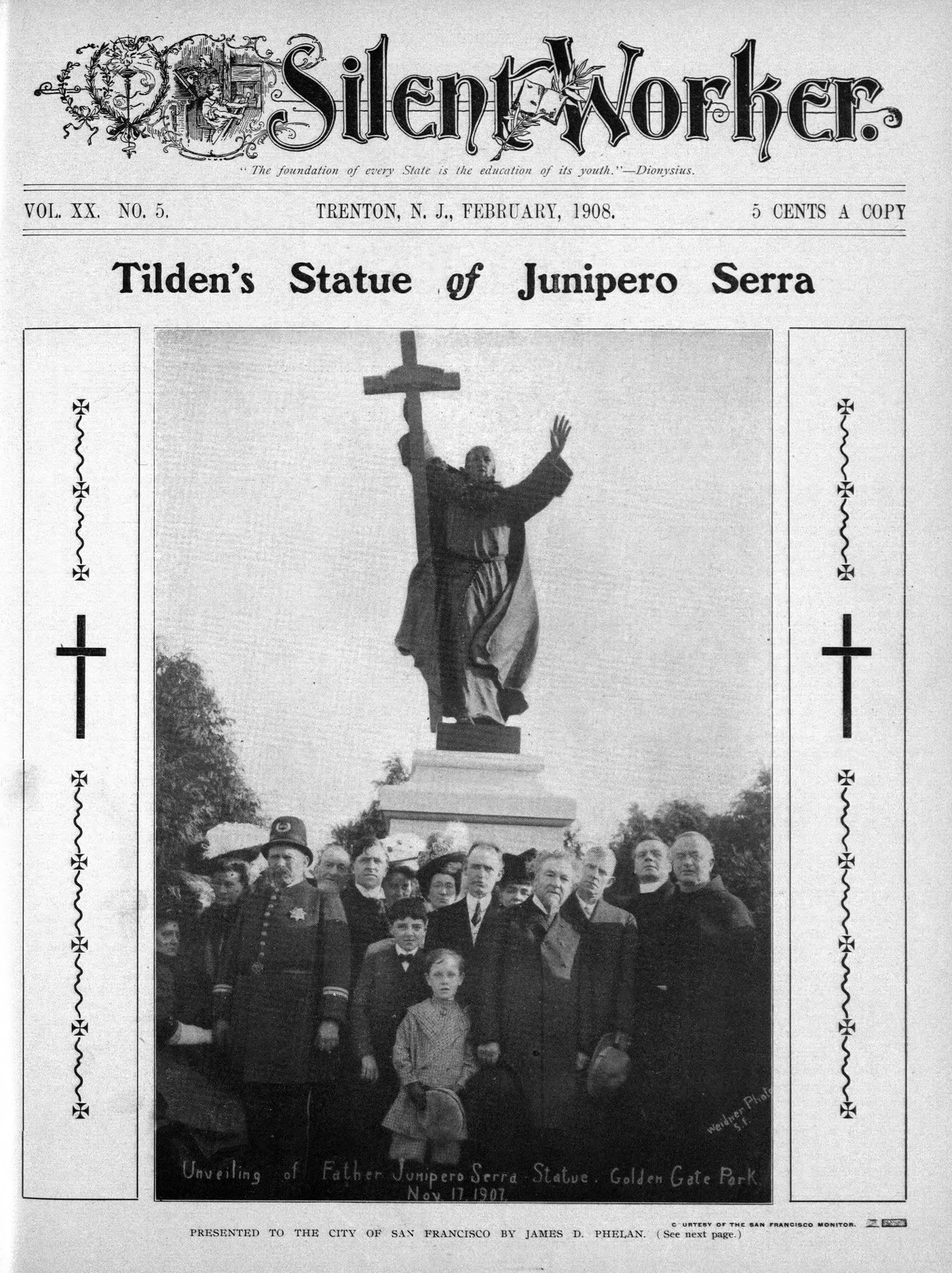

A statue installed in a mythmaking project and toppled in a burst of iconoclasm, for all the uproar about its removal in 2020, the trajectory of the Junípero Serra monument in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park is a deeply normal American story.

Sculpted by noted deaf sculptor Douglas Tilden on a commission from virulently racist former San Francisco mayor James Phelan and dedicated in 1907, this Junípero Serra statue was a remnant of a decades-long marketing effort to inflate the Franciscan missionary into the father of (white, European, Christian) California. Serra founded and led a string of nine missions in Spanish Alta California where Native Californians like the Ohlone—in the midst of an ecological collapse and health catastrophe—took refuge to survive. Once baptized, though, they were prevented from leaving and forced to work, with the Franciscans siccing the Spanish military on anyone who tried to escape. Serra’s leading role in a system defined by forced labor, colonial domination, and cultural extermination represented a vulnerability in the mythmaking project. Over the last few decades a counternarrative gained momentum, sparking a popular reexamination of the wicked core of the Serra myth—the toppling of this Junípero Serra in 2020 was part of a broader removal of Serra monuments over the last decade.

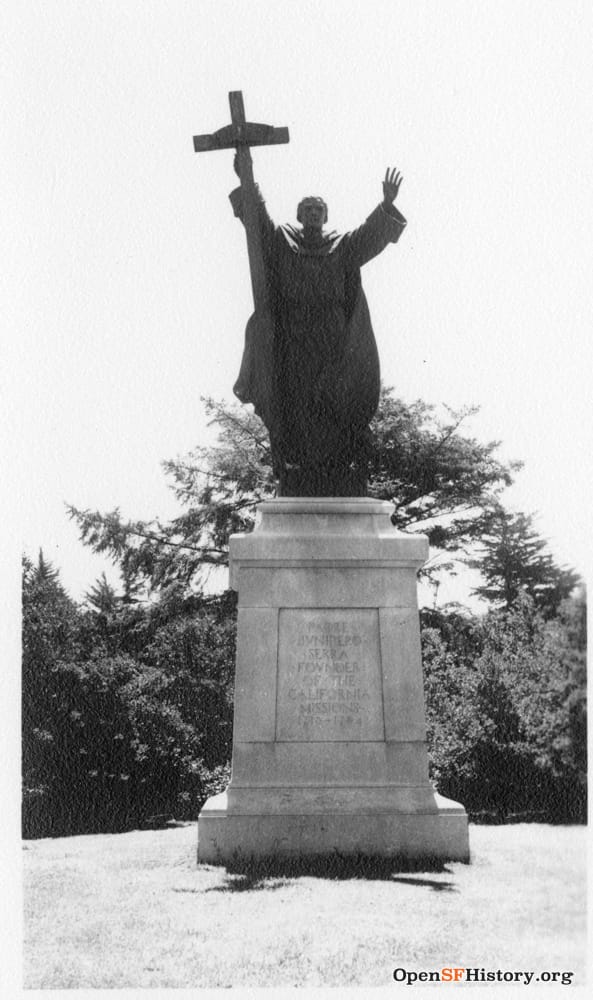

…plus, honestly, this statue was shoddy work, nowhere near Tilden’s best.

So, what’s changed, besides the incredibly obvious?

- Bigger road through the park, because of course.

- The change in vegetation speaks to a change in the values of landscape architecture, but one I’m not really qualified to interpret.

- …Tilden’s statue now sits in storage after it was pulled down in 2020.

Father Junípero Serra landed in New Spain in 1749, as the Spanish Empire started to stretch thin. A Franciscan missionary in the twilight of the Spanish mission system in the New World, Serra took advantage of his autonomy and, uh, divine blessing to found a string of nine missions up and down the coast of Baja and Alta California. Serra’s missions opened in a California wracked by ecological collapse and health catastrophe (sparked by, yes, the colonial enterprise). To survive, natives sought refuge through baptism into the mission system—but once baptized, they were prohibited from leaving, despite disease, poverty, and death. Yet for all the disastrous effect that the California missions had on native peoples like the Ohlone, after the death of Serra in 1784, he was basically a footnote in the area’s history for the next century.

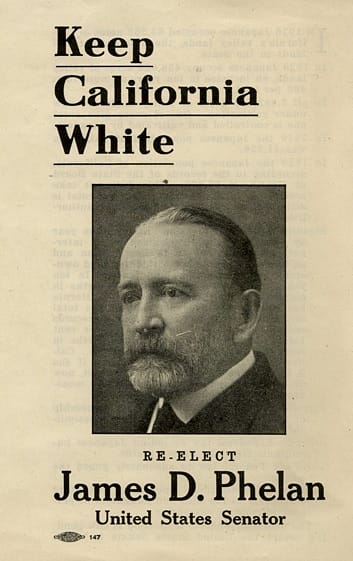

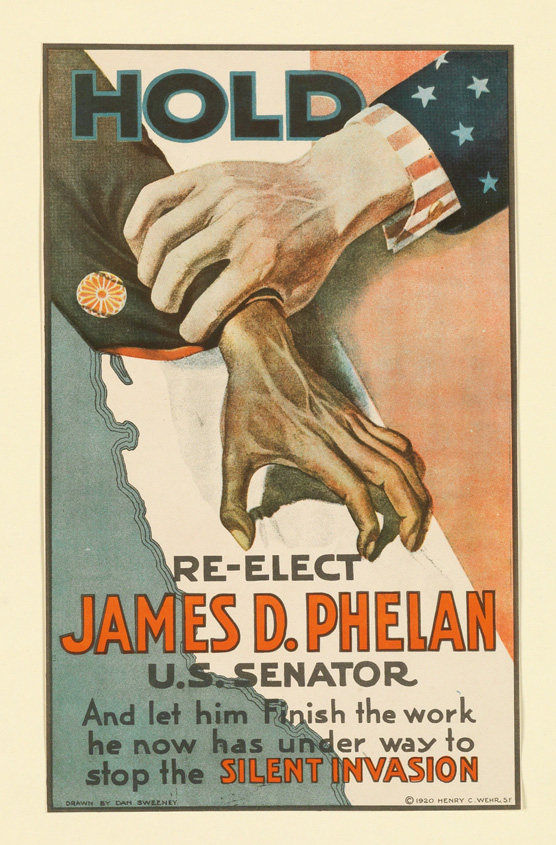

Only in the late 1800s—with Asian immigration to the state rising, along with a racist backlash to those migration flows—was Serra’s story revisited in an effort to knit together a coherent California culture for the white Americans settling the state. The Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882, and the 1890s saw the installation of the first monuments honoring Serra across the state. In this environment—white settlement, Native repression, and Asian exclusion—San Francisco elected James D. Phelan as mayor. An adherent to the City Beautiful movement, during his tenure, Phelan organized a nine-member commission focused on the public adornment of the city—which included Bay Area sculptor Douglas Tilden—and with the help of the committee, Phelan commissioned several public monuments of past leaders, men of genius, and fallen heroes to mythologize a sense of shared history. Phelan was also an enormous asshole—virulently anti-Chinese, anti-Japanese, and anti-immigrant, he’d later run for senate on a platform of “Keep California White”.

1920 reelection ad, Wikimedia Commons | 1920 reelection poster, Wikimedia Commons

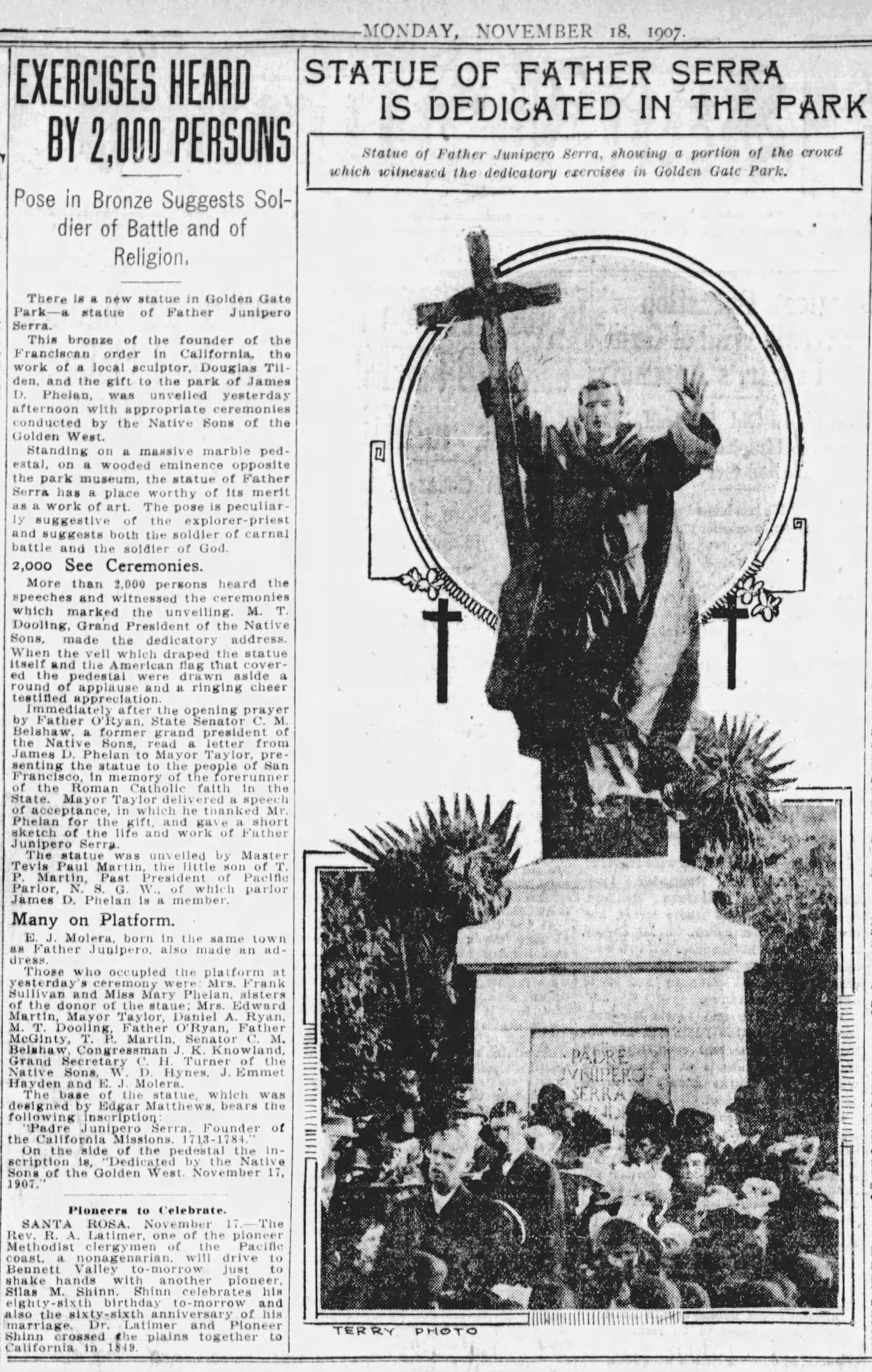

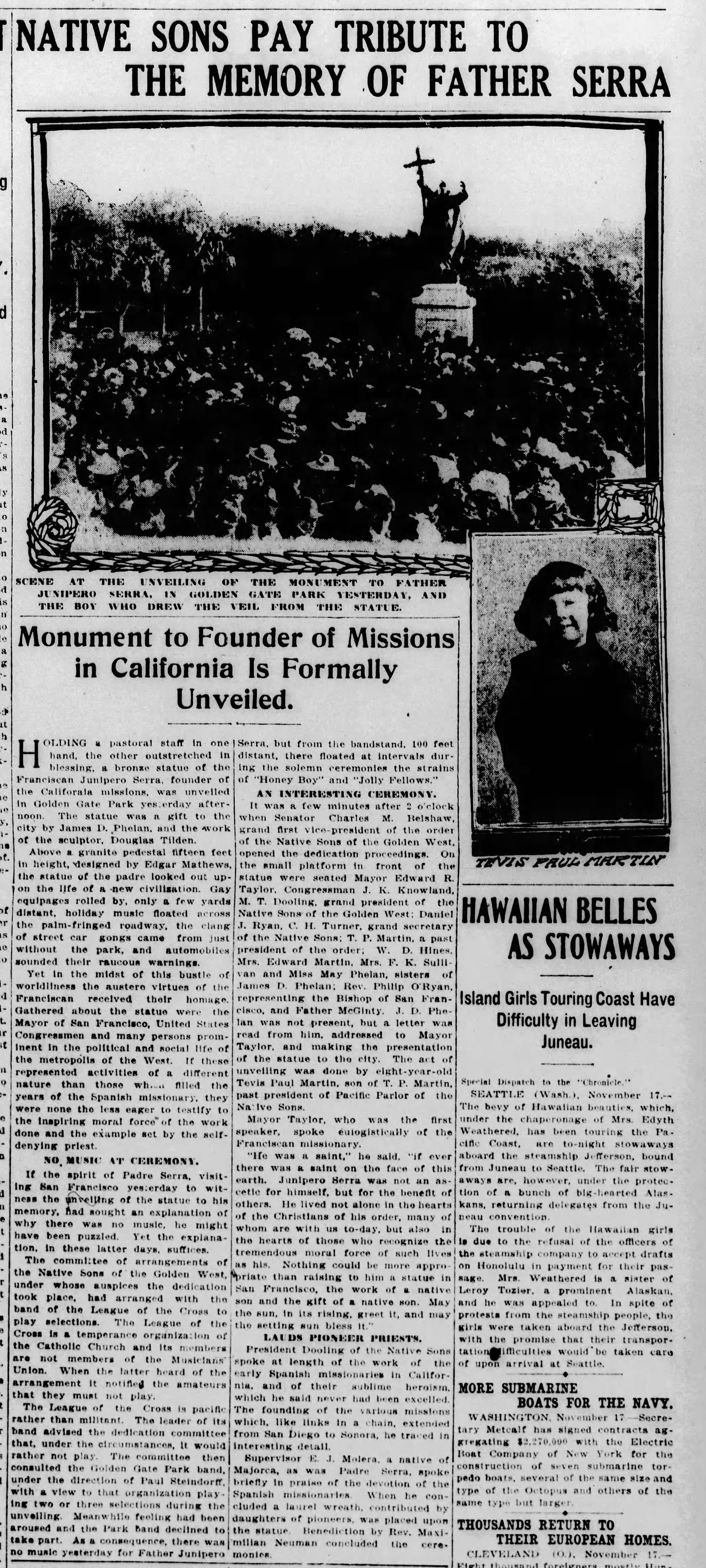

Phelan so believed in the power of monument building to mold a patriotic, cohesive polity that he pressed forward even after his mayoral term ended in 1902. In 1905—as a private citizen—he commissioned his artist of choice, Tilden, to craft a monument to his chosen founder of California, which he would donate to Golden Gate Park on behalf of the Native Sons of the Golden West (Phelan was a Native Son).

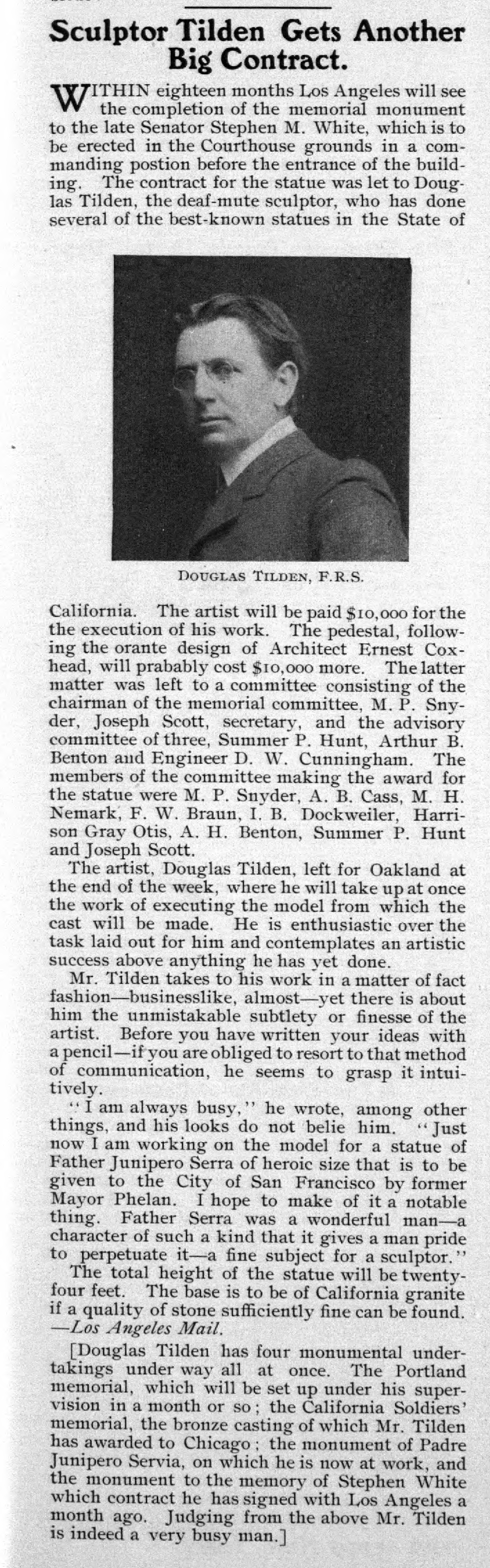

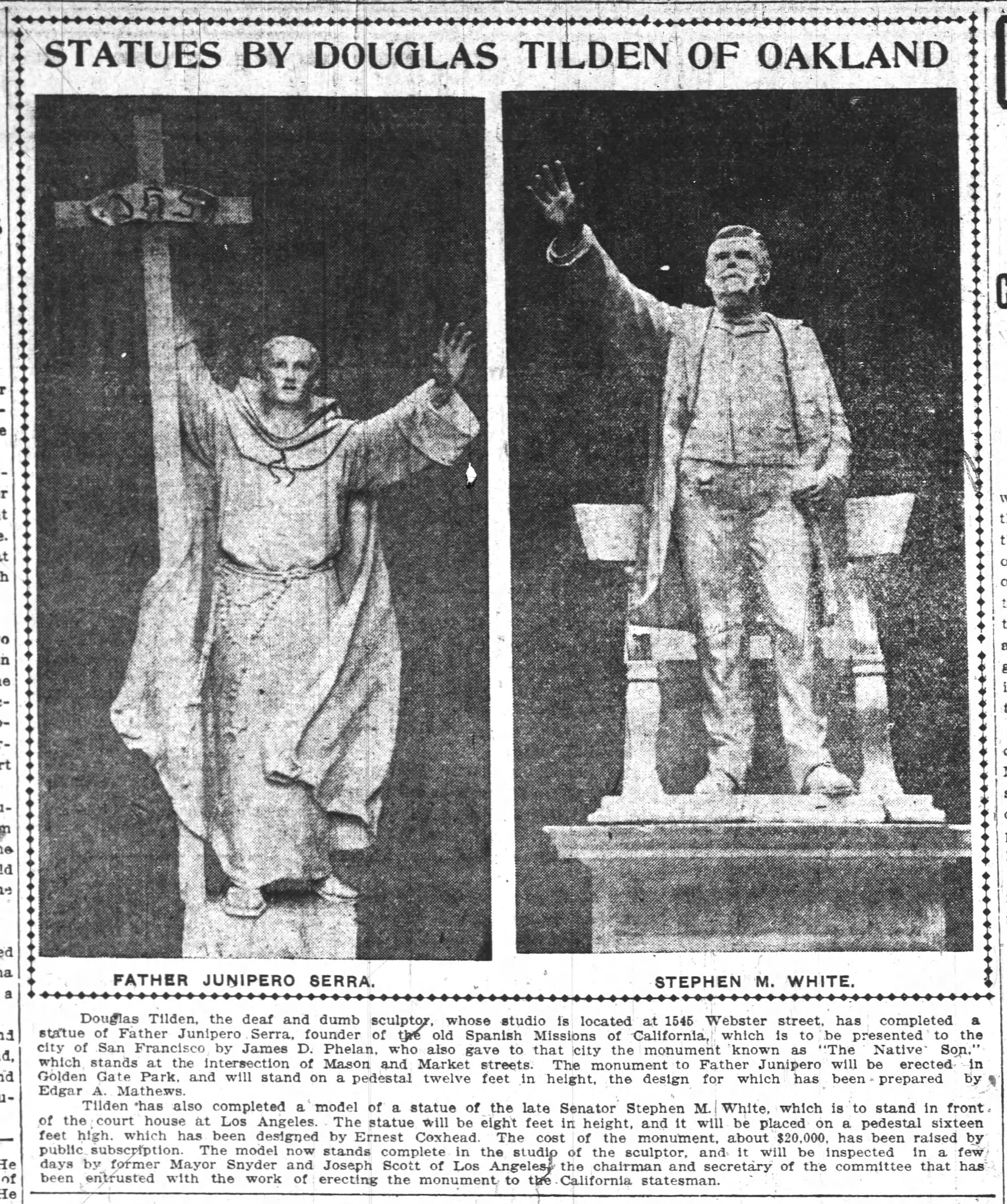

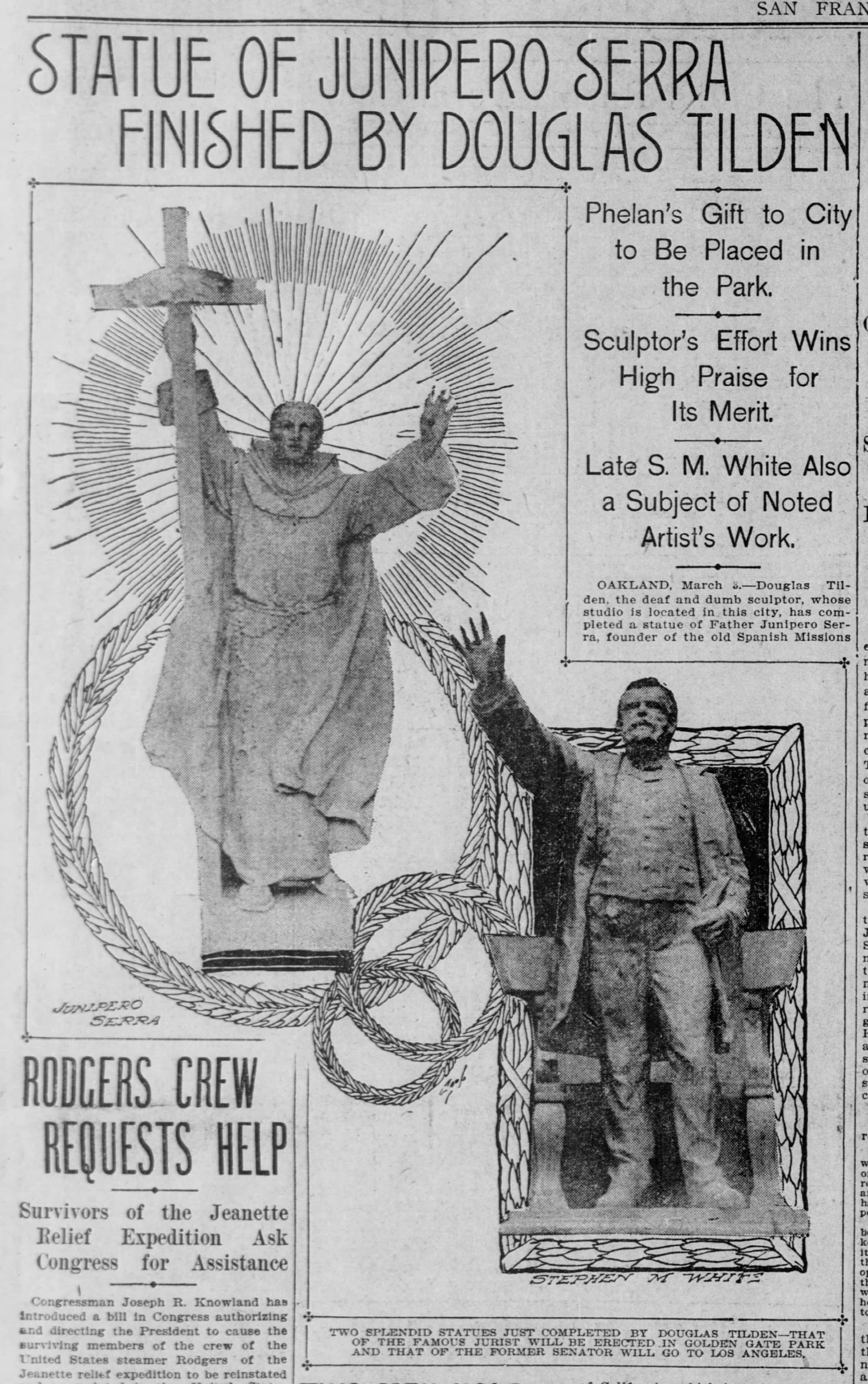

Douglas Tilden was a major sculptor in the 1890s and 1900s in the Bay Area, and a hero to the deaf community (he’d lost his hearing as a small child to scarlet fever). Phelan funded the monument, which cost $12k (more than $400k in 2025). Created at Tilden’s studio in Oakland, the mold of the Serra statue escaped the 1906 earthquake unscathed and was sent to the American Bronze Company in Chicago for casting that year. This would be one of Tilden’s last major monumental works. The plinth was designed by Edgar Mathews.

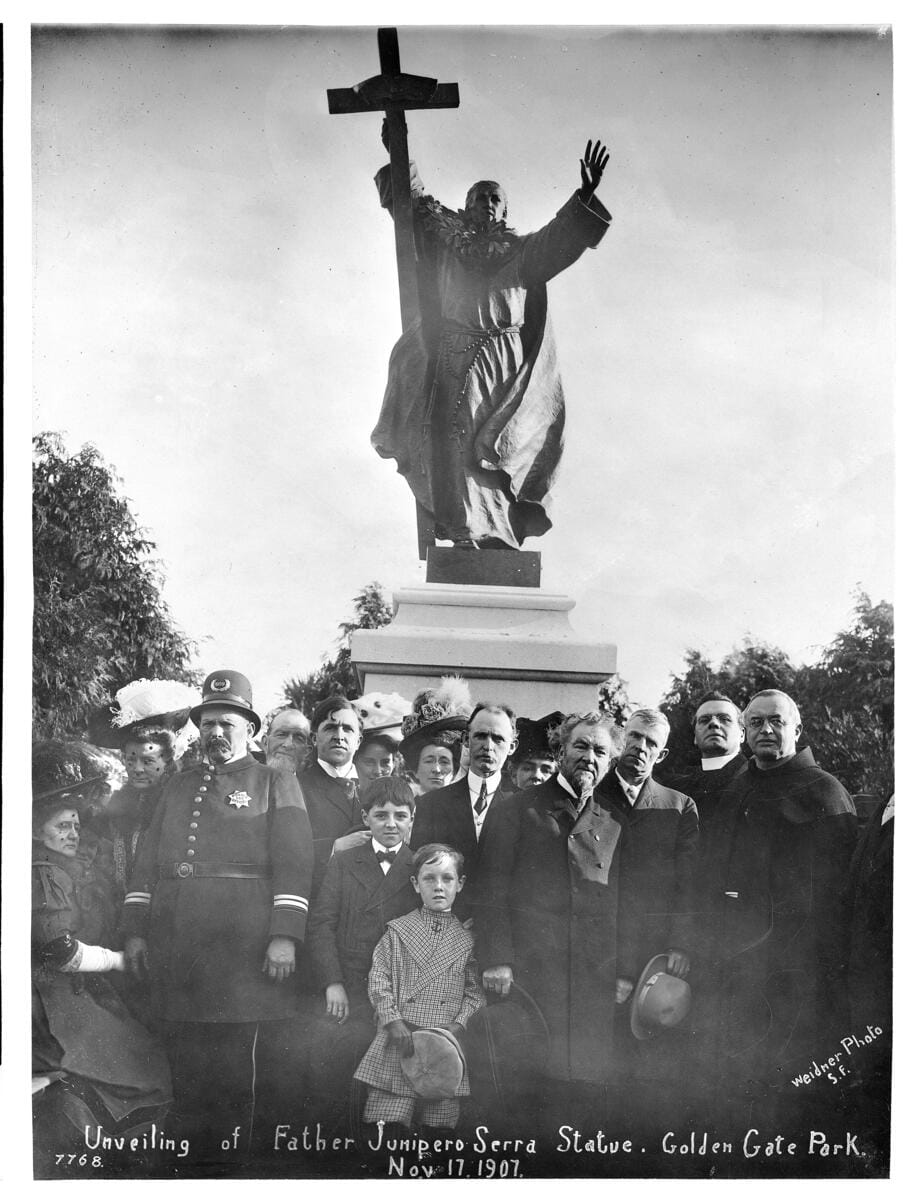

1906, Tilden wins contract, the Silent Worker, the Internet Archive | 1906 article on statues by Tilden, Oakland Tribune | 1906, statue finished, San Francisco Call | 1906, casting finished, San Francisco Call | 1907, dedication, San Francisco Examiner | 1907, dedication, San Francisco Chronicle | Unveiling, 1907, CHS-7768, University of Southern California Libraries and California Historical Society | 1910, California State Library | 1920s, OpenSFHistory / wnp15.564 |

Dedicated in 1907 to great fanfare with thousands in attendance, this was one of dozens of Serra statues that went up across California in the 1900s: San Diego in ~1910, Carmel Woods, in 1922, the US Capitol in the late 1920s, Los Angeles in 1932, Ventura in 1936, Sacramento in 1967, San Luis Obispo in 1970, and in Hillsborough on Highway 280 in 1975 (one of the earliest, in Monterrey, was installed in 1891).

Tilden’s monument—again, kind of a clumsy depiction in my opinion—sat here, in the original Music Concourse section of Golden Gate Park, kind of inert for about a century. A decolonial counter-narrative grew in opposition to Serra’s symbol as part of the mythology of the American West, even as the Catholic Church fast-tracked Serra on the path to canonization as a saint. Turns out that when even contemporary Spanish colonial military accounts said that your cruelty drove people out of the missions, people would organize centuries later to fight your lionization.

Undated, OpenSFHistory / wnp15.1148 | 1920s, OpenSFHistory / wnp70.10038 | 1937, OpenSFHistory / wnp27.1369 | 2015, Burkhard Mücke, Wikimedia Commons | 2023

St. Junípero was canonized in 2015, but most of those aforementioned Serra monuments have been removed, either through spontaneous protest or deliberate government action. Protestors toppled this one on June 19th, 2020. Still in the possession of the City of San Francisco, but in storage, it will not be returning to its plinth.

…and honestly, that’s fine—the American project is all about the making and unmaking of myths. We don’t need this one anymore.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Children of Coyote, Missionaries of Saint Francis: Indian-Spanish Relations in Colonial California, 1769-1850 by Steve Hackel

- Converting California: Indians and Franciscans in the Missions by James A. Sandos

- "Douglas Tilden's Mechanics Fountain: Labor and the "Crisis of Masculinity" in the 1890s" by Melissa Dabakis

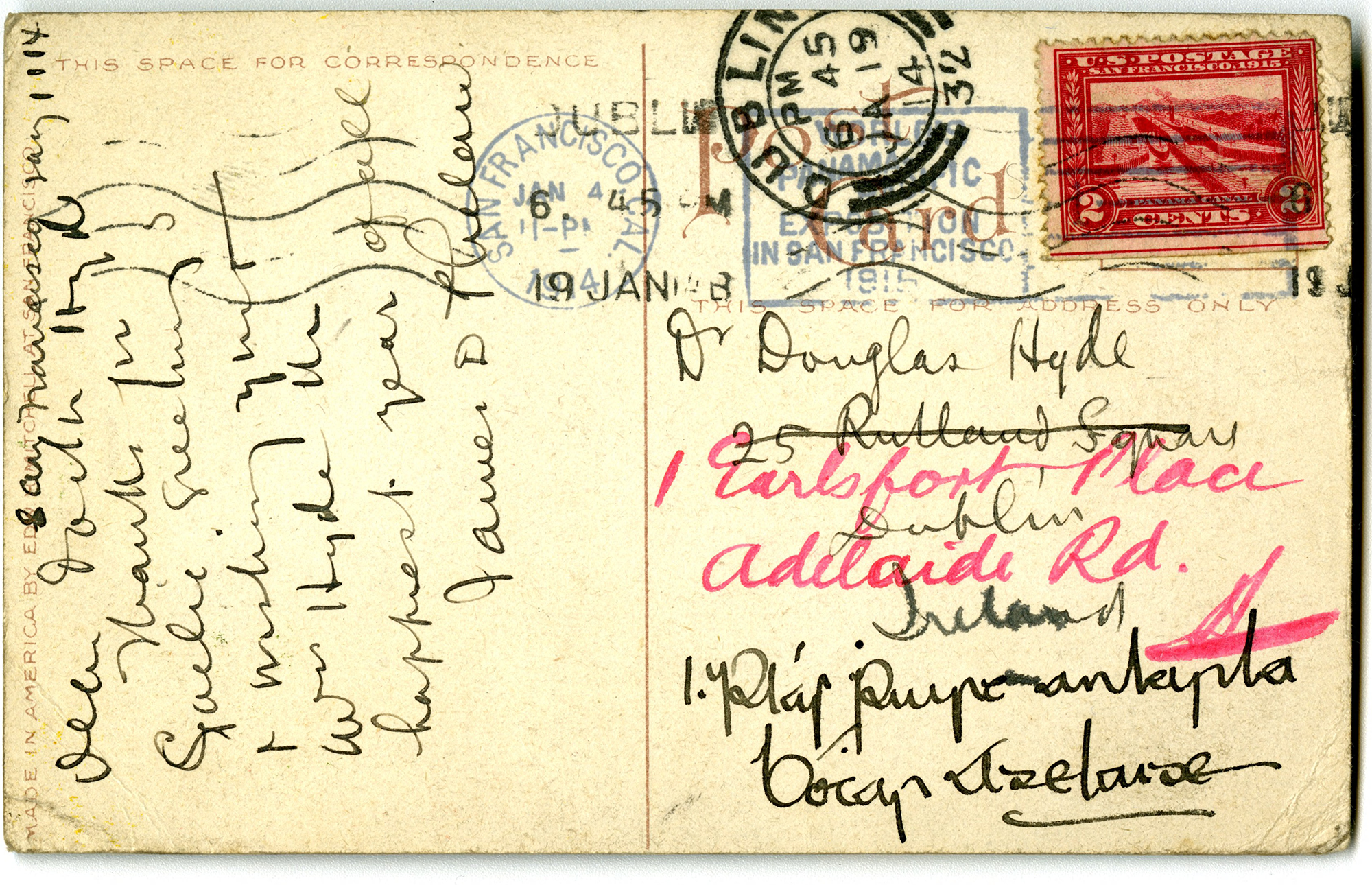

This postcard is an interesting document itself—Phelan, Irish-American, sent this to Irish linguist, Gaelic League founder, and future President of Ireland Douglas Hyde as a New Year's greeting in 1914.

"Dear Doug Hyde,

Thanks for Gaelic greetings + wishing you + Mrs. Hyde the happiest year of all"

The sculptor here, Douglas Tilden, was a huge deal in the American deaf community—a renowned working sculptor and, for a while, a teacher at the California School for the Deaf.

Monuments to Serra sprouted across California in the 1900s, including these four, which have all been removed, except for the one in Monterey.

Junípero Serra's Monument, Monterey, Wikimedia Commons | Father Junípero Serra by Arthur Putnam in San Diego, University of Southern California Libraries and the California Historical Society | Junípero Serra monument in Los Angeles, University of Southern California Libraries and the California Historical Society | 1982, San Bruno, Wikimedia Commons | 2013, Nathan Hughes Hamilton, Wikimedia Commons

Here's where I took the photo from.

Member discussion: