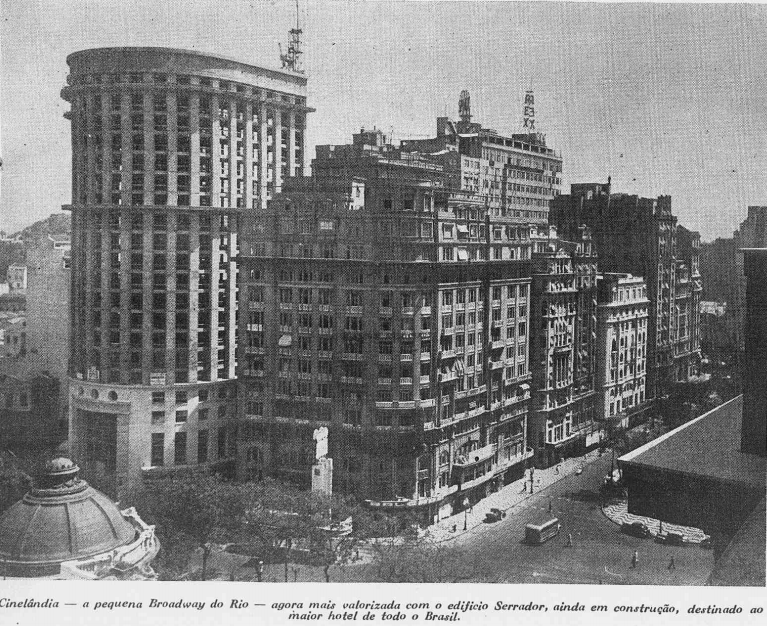

Intended as a swaggering capstone to the eternal vibrancy of Cinelândia, the largest and most lavish hotel in Brazil when it opened in 1944, the Hotel Serrador turned out to be the swan song of Cinelândia’s golden era. Francisco Serrador—the entertainment tycoon who turned Praça Floriano into Cinelândia, a theater and cinema district that he envisioned as Brazil’s answer to Times Square—died before the tallest building in his portfolio opened, designed by architect Stélio Alves de Souza in an austere Art Deco reminiscent of the Depression Deco of the 1930s in the US.

By the late 1960s Cinelândia and the Serrador were in decline. Now, after a few decades of chaotic vacancy and failed revitalization efforts, the Edifício Serrador finally has a permanent use—the Municipal Chamber of Rio de Janeiro bought the building for R$149m ($28.5m) at the end of 2022 and the building in currently in the midst of a massive renovation to turn it into the headquarters for the city’s legislature.

So, what’s changed? Well, first off, yeah, I flubbed the angle a little bit—I know—but there’s a mildly exculpatory excuse: when this postcard was published, the Palácio Monroe stood in front of the Edifício Serrador. When it was demolished in 1976 and replaced with the Praça Mahatma Gandhi, the reconfiguration of the streets for the new plaza claimed the little promenade this photo was taken from—it’s now a service road (but yes, I mostly just bungled this, but I won’t be back in Rio anytime soon so). The other notable change is the activation of the top floor and the addition on top, part of a 2009 renovation.

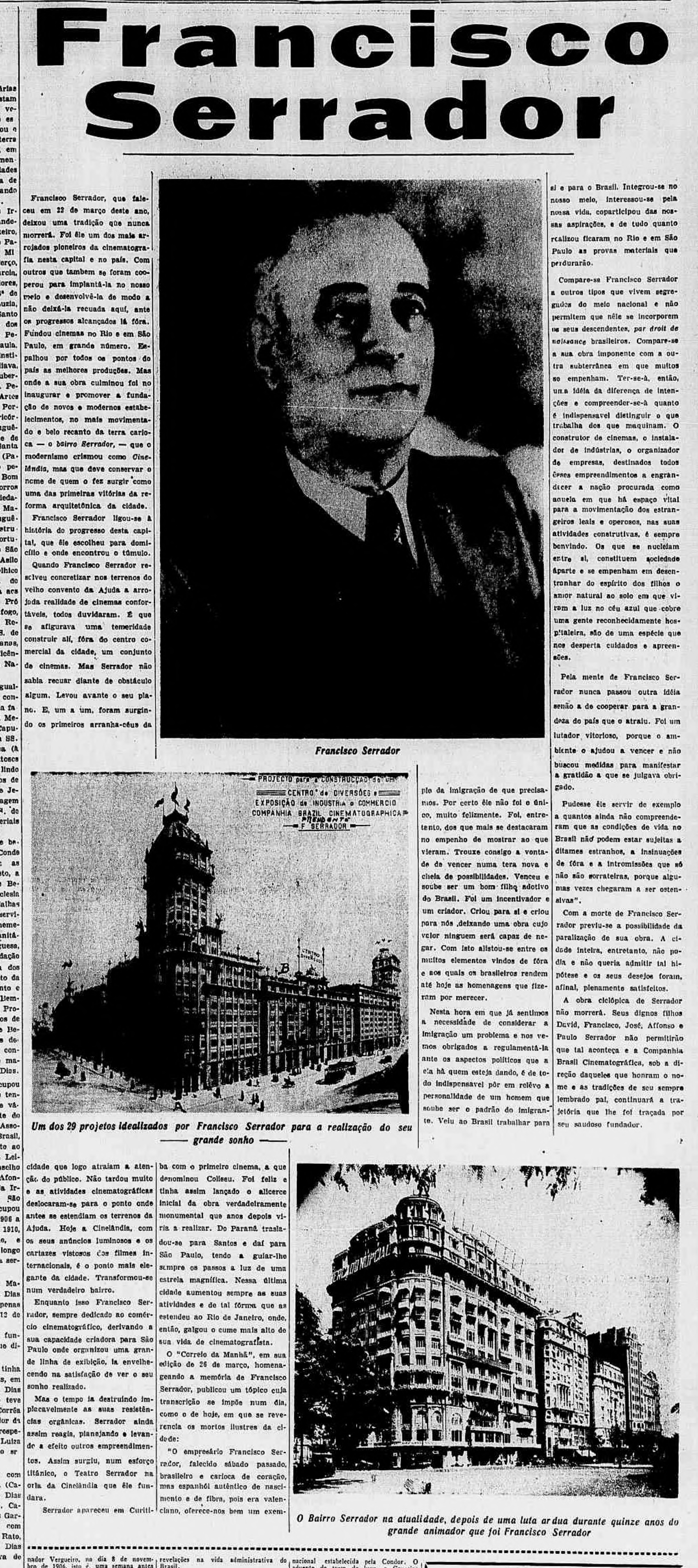

A Spanish immigrant to Brazil, Francisco Carbonell Serrador built an early cinema empire in São Paulo, one that launched him into Rio in the late 1910s, where his company swelled into a film distribution and exhibition giant that dominated the market. Inspired by Times Square and Broadway, the Serrador spent the 1920s and 1930s amassing an entertainment empire of cinemas, hotels, casinos, and theaters that turned the neighborhood around Praça Floriano into Cinelândia.

Francisco Serrador, Wikimedia Commons | Cine Alhambra, BNDigital | 1939 articles about the demolition of the Alhambra, the Internet Archive | 1940 articles about the Alhambra fire, the Internet Archive

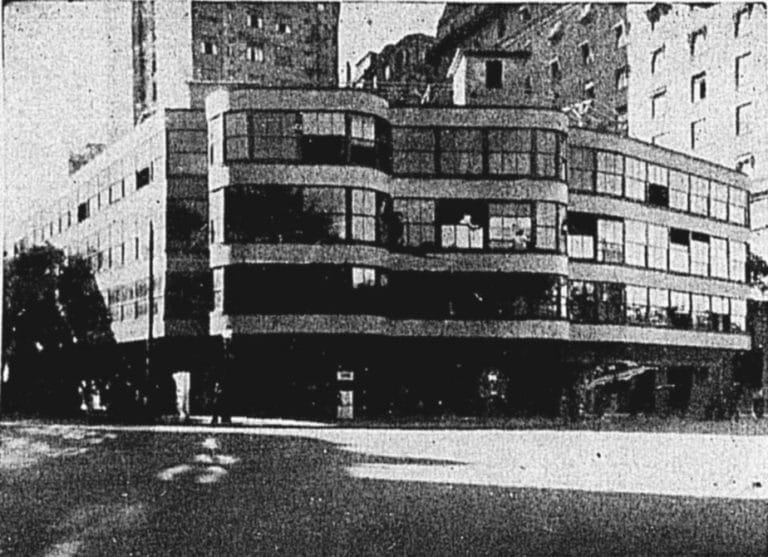

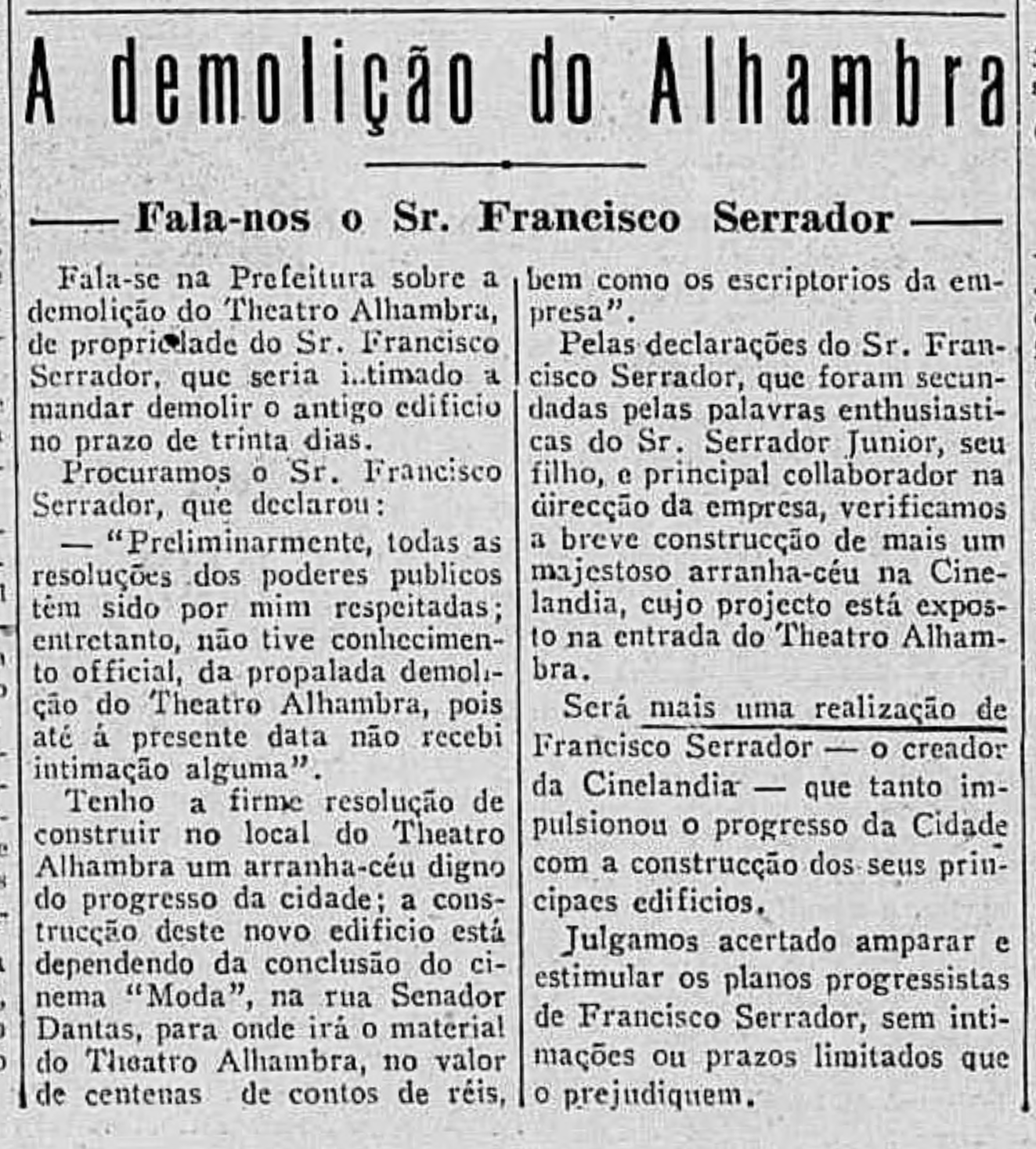

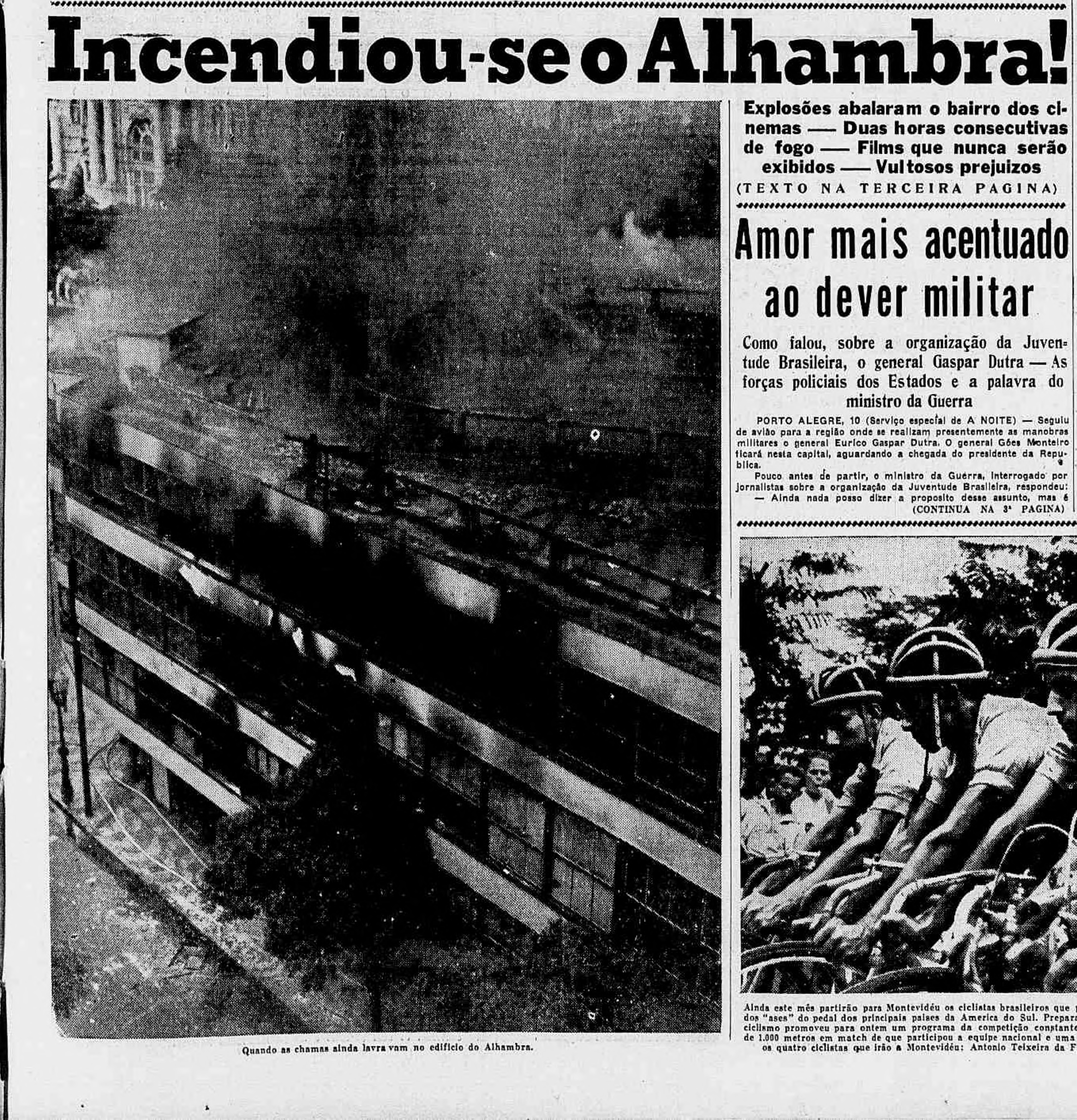

On this site in 1932, Serrador’s company opened the Cine Alhambra, a nifty Bauhaus-looking building designed by Arnaldo Gladosch. The Alhambra was a placeholder building, with Serrador intending to build a skyscraper on this site eventually. In 1939 the city demanded the demolition of the Alhambra. Serrador closed the cinema, but before demolition could begin, the Alhambra burned down. While it wasn’t hosting movie screenings any longer and some of the tenants had moved out already, the Serrador company used the Alhambra to store (notoriously flammable) film reels and the fire destroyed 2500 reels, including at least a couple never-released films.

On the ashes of the Alhambra, Francisco Serrador and his sons planned the capstone to his Cinelândia empire, hiring architect Stélio Alves de Souza to design a curving 400-room hotel overlooking what was then known as Praça Getúlio Vargas. Serrador wanted his hotel to be the largest and most luxurious hotel in Rio. It was seen as an ambitious project at the time, even for a guy credited with creating a whole neighborhood’s identity. Unfortunately for him, Serrador would never bask in the splendor of his fancy hotel—he died in 1941, shortly after construction began.

1941, Serrador Obituary, the Internet Archive | ~1942 construction photo | 1943 construction photo, A Cena Muda | 1944 articles about the dedication and opening of the Hotel Serrador, the Internet Archive | Hotel Serrador luggage tag

Francisco Serrador’s five sons took over the company, led by David, and the Alves de Souza-designed hotel opened to the public in 1944. Lucio Costa credited Stélio Alves de Souza as the first Brazilian architect to put a building on pilotis, the stilt-like columns that lift a building (say, the Ministry of Education and Health Building) off the ground. The Hotel Serrador couldn’t be further from that, meeting the ground strong and austere with a monumental entryway. Often described as Art Deco, it evokes the classical moderne or Depression Deco common in US federal buildings in the 1930s while also hinting at an inflection point between Art Deco and modernism.

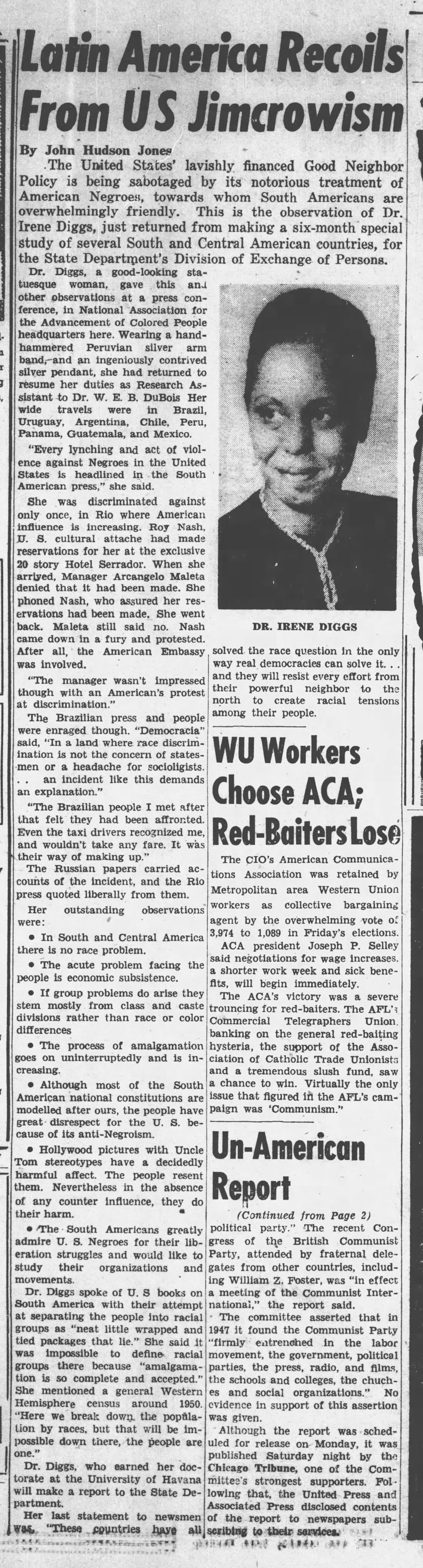

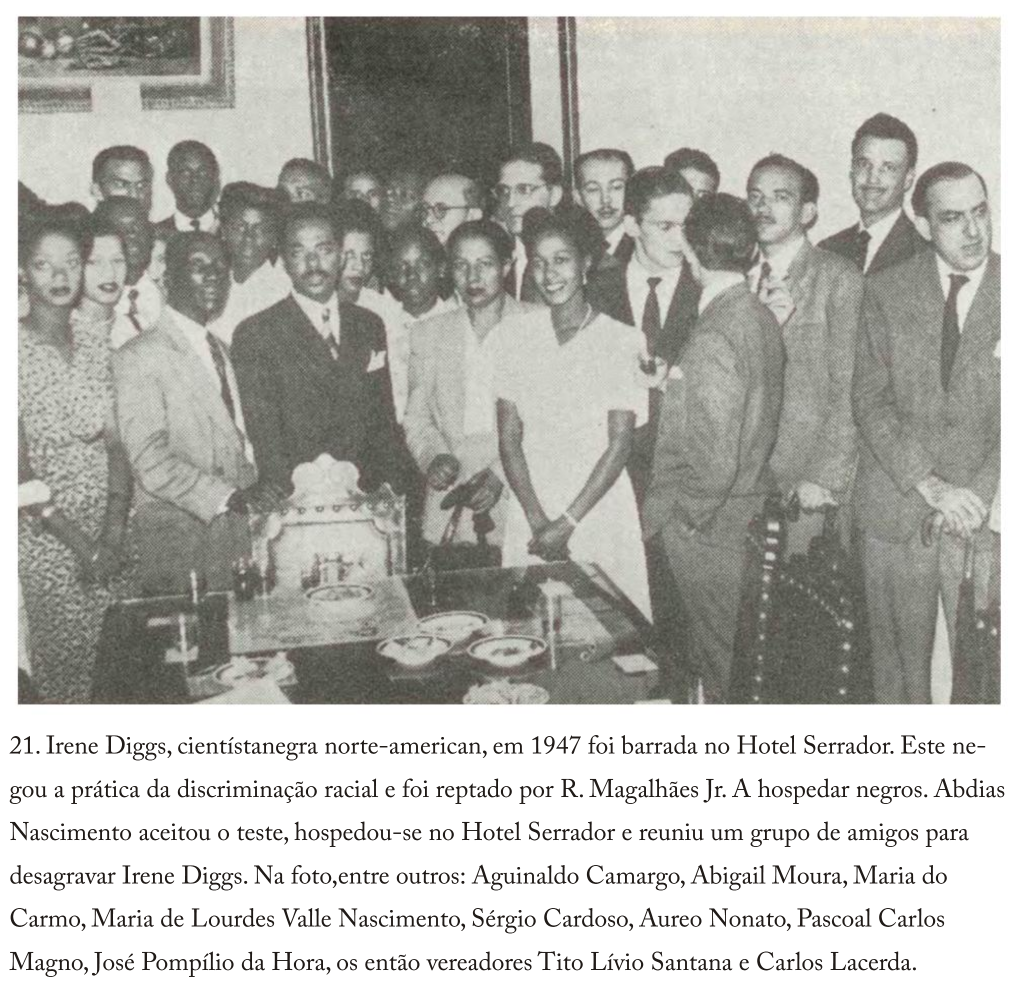

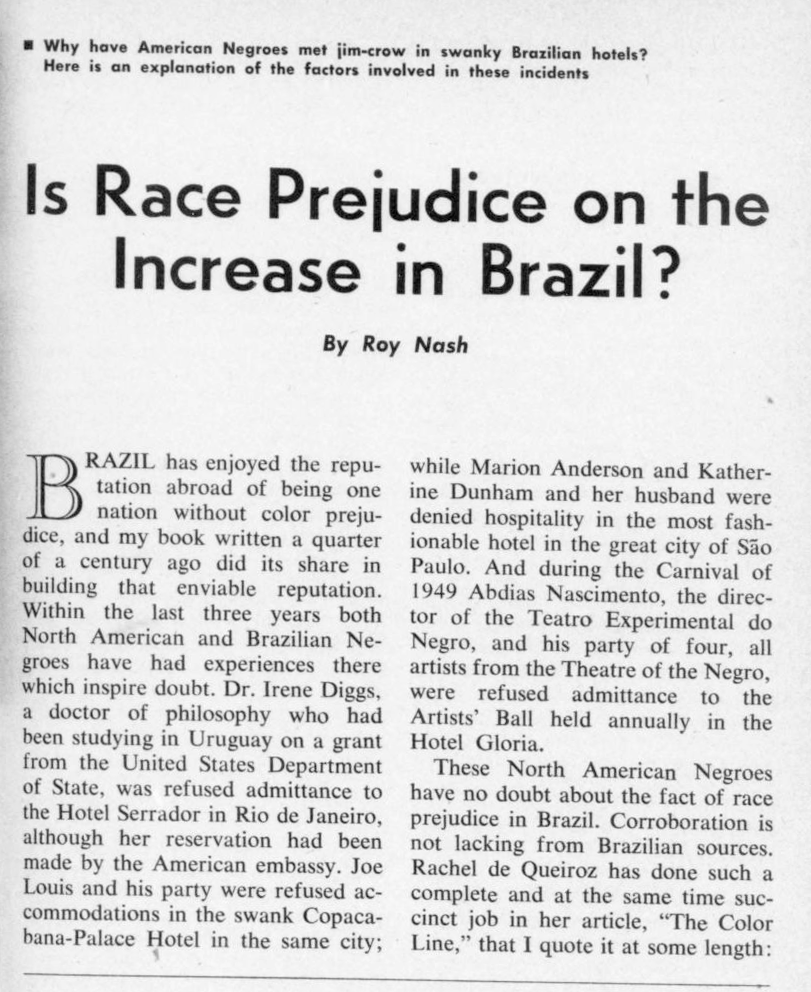

Hotel Serrador—and its in-house nightclub, Night and Day—was a Rio hotspot for tourists and locals into the 1960s. Although not for everyone: in 1947 the hotel turned away visiting African American anthropologist Irene Diggs, foreshadowing how Brazilian hotels would treat dancer Katherine Dunham in the 1950s, a scandal which helped embarrass Brazil into passing antidiscrimination laws.

1947 article about Irene Diggs being turned away | 1947, demonstration against the Hotel Serrador, O negro revoltado | 1951, the Crisis asks, "Is Racial Prejudice on the Rise in Brazil", the Internet Archive | Undated photo of Paris Square with the Serrador Building in the background, Werner Haberkorn, Ipiringa Museum, Wikimedia Commons | 1974, pastvu.com | mid-1970s demolition photos of the Palácio Monroe with the Hotel Serrador in the background

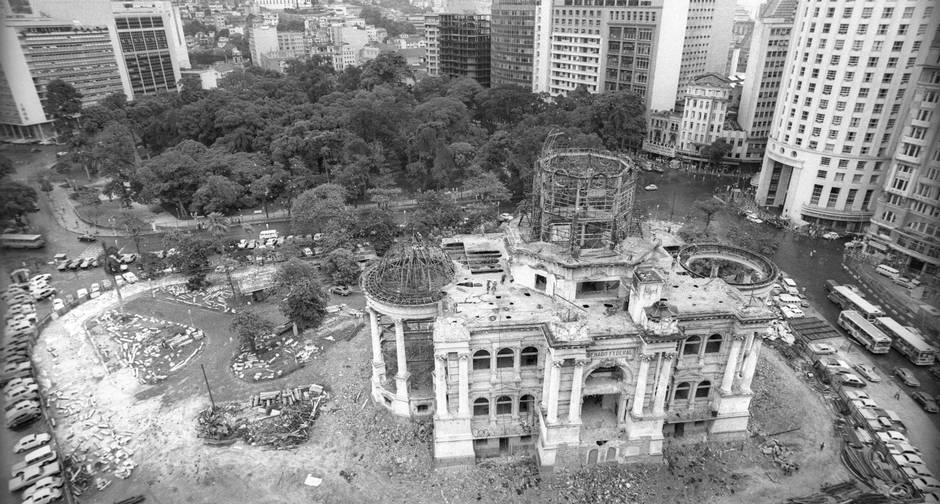

Cinelândia, already eroding as an entertainment district by the 1950s and 1960s, struggled with decay and vacancy, especially after the Brazilian capital moved from Rio to Brasília. Night and Day had been popular with Brazilian senators working in the Palácio Monroe across the street—a clientele that left with the rest of the federal government in 1960 (and the Palácio Monroe itself would be controversially razed in 1976).

Hotel Serrador closed in the 1970s. In 1977, Petros—the pension fund for Petrobras employees—bought the building and converted it into their office headquarters. Petros moved out in 1997 and the building sat vacant for a few years. Windsor Hotels bought and renovated the building in 2009 (but—confusingly—intended to operate it as offices), then leased it out to Eike Batista to serve as the headquarters for his EBX Group. Briefly one of the richest people in Brazil, Batista’s companies would soon implode (and he himself would end up in prison on money laundering and bribery charges). The building received a heritage listing in 2015 protecting the facade, but with the collapse of EBX Group and the building owner—Windsor Hotels—challenged financially, the building sat vacant and decaying.

After a few tumultuous decades, it was government that brought the Serrador Building out of purgatory—the Municipal Chamber of Rio de Janeiro bought the building for R$149m ($28.5m) at the end of 2022. Through consolidating a handful of office buildings used by the legislative branch of the city’s government, turning the Serrador Building into the Municipal Chamber’s HQ should save the government millions in rent. Many workers have already moved in, but the city government expects to fully wrap up the renovation of the Serrador Building this year.

Local government revitalizing an aging landmark, you love to see it.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Arquitetura do espetáculo: teatros e cinemas na formação da Praça Tiradentes e da Cinelândia by Evelyn Furquim Werneck Lima

- Petros 40 anos: uma história sem fim

- "Arnaldo Gladosch: o edifício e a metrópole" by Anna Paula Moura Canez

- "Among Four Hotels: Anti-Racist Public Policy In Brazil" by Sérgio José Custódio

- Great Flickr album from the chamber, focused on the interiors after the renovation

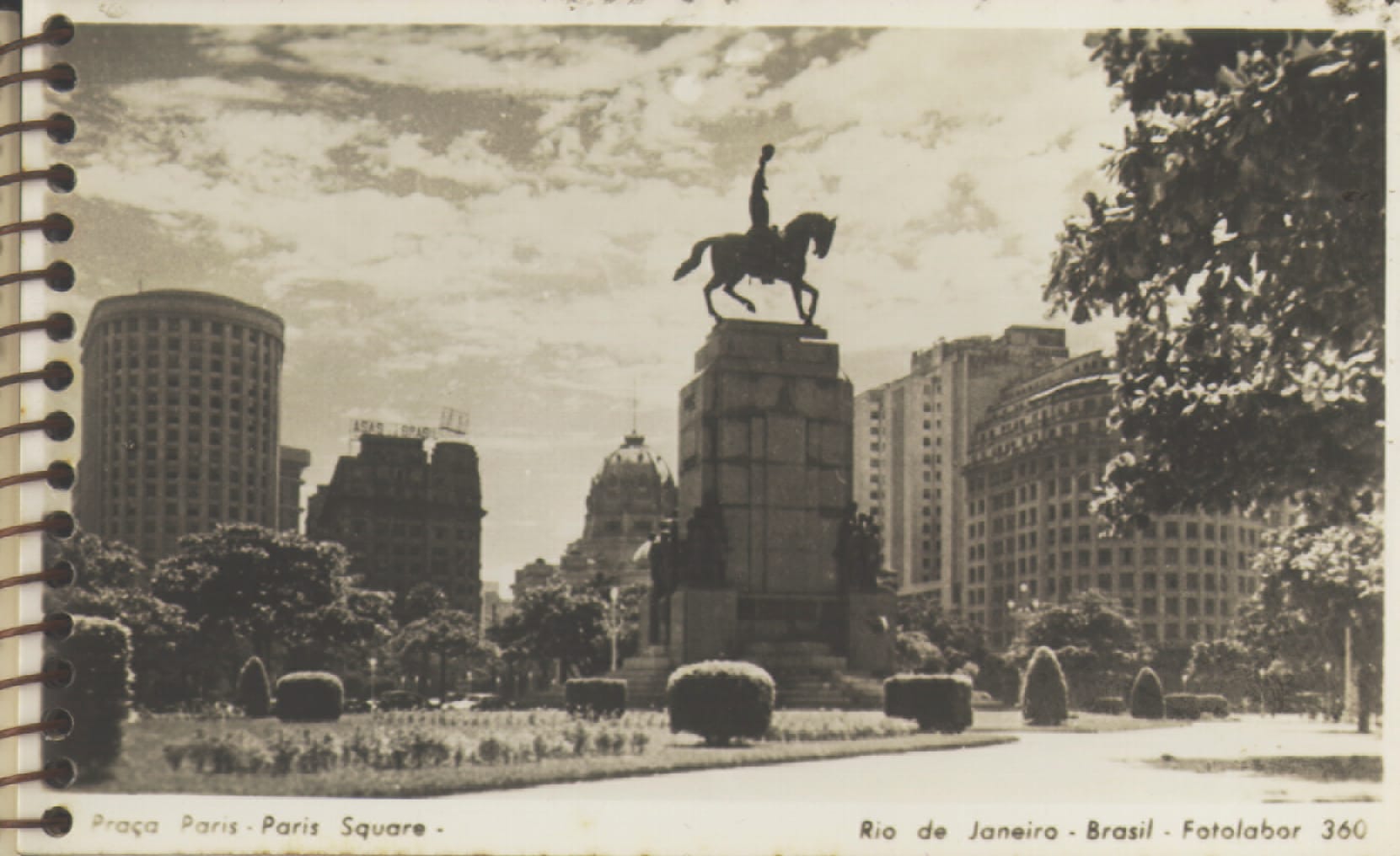

Some interesting perspectives on parks and public space here—some that hasn't changed at all, like the Praça Paris.

Undated photo of Paris Square with the Serrador Building in the background, Werner Haberkorn, Ipiringa Museum, Wikimedia Commons | Paris Square, 2015, Wikimedia Commons

...others that are completely different, like the Praça Mahatma Gandhi in front of the Serrador Building.

1921 aerial photo, Jorge Kfuri, Instituto Moreira Salles | 1926-1934 aerial, Instituto Moreira Salles via Wikimedia Commons | 1975 demolition of Palácio Monroe | Undated, Mahatma Gandhi Square where the Palácio Monroe stood

I appreciate that this Boston-based postcard maker still localized the verso with "cartão-postal".

Member discussion: