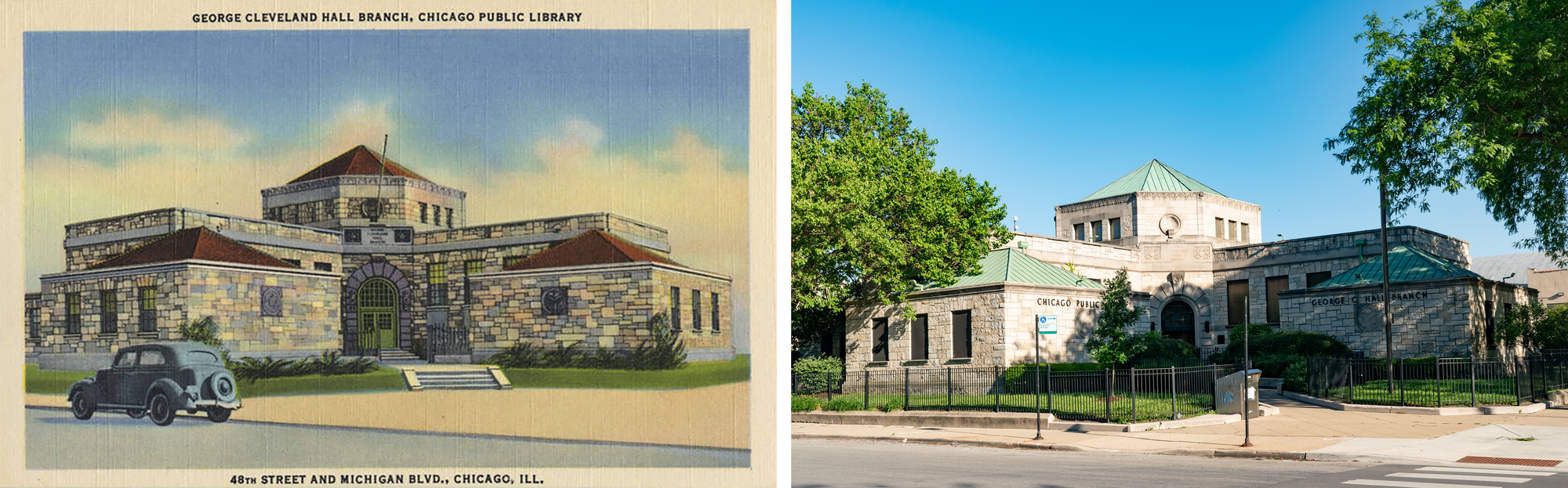

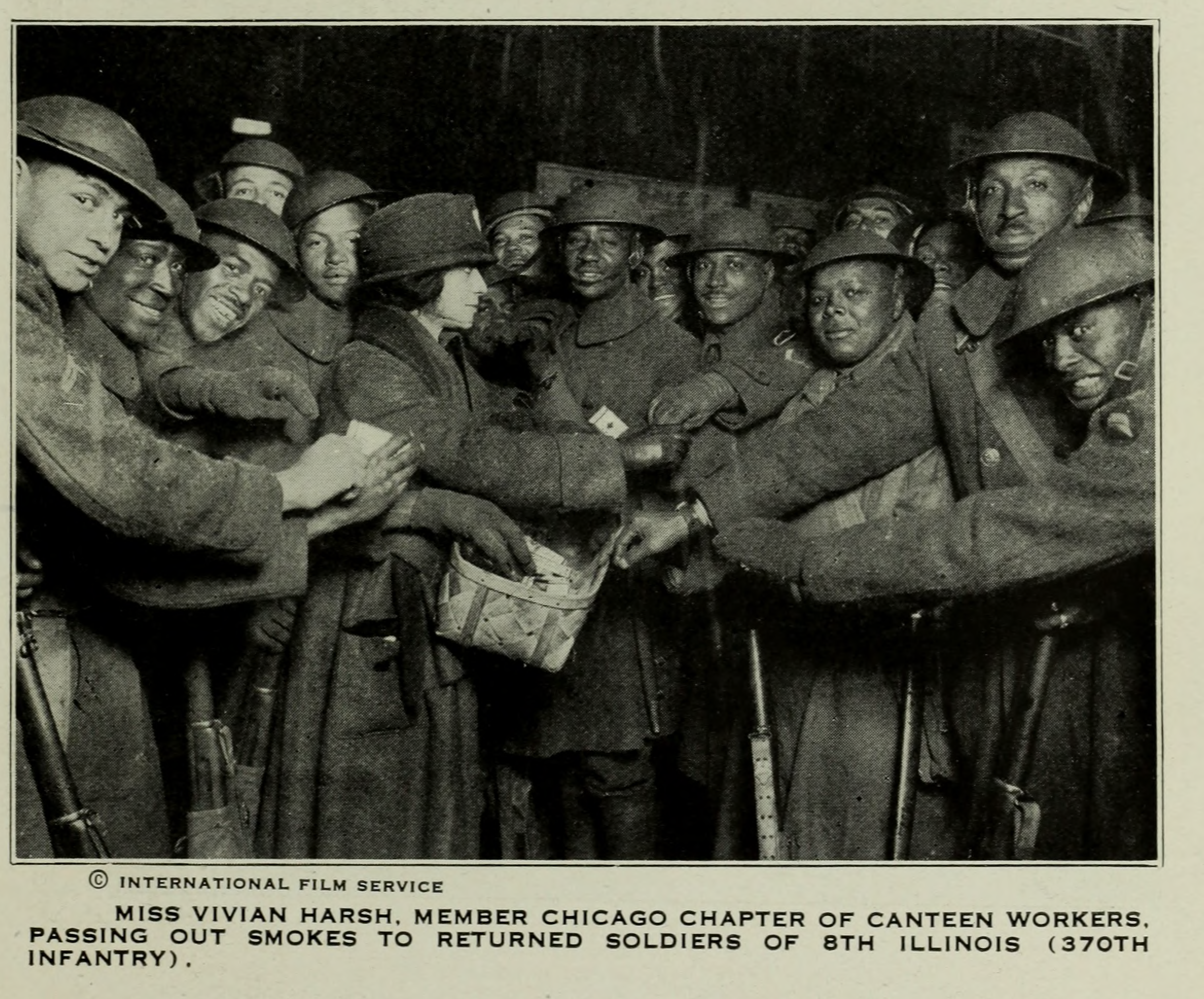

The enigmatic octagon atop the George Cleveland Hall Branch of the Chicago Public Library caps one of the most important libraries in the city. The first public library in Chicago to serve a predominantly Black community, the Hall Branch nurtured the talents of writer Richard Wright, poet Gwendolyn Brooks, artist Charles White, Dr. Margaret Burroughs, Timuel Black, and Mayor Harold Washington, amongst countless others. The names of Hall Branch employees Vivian Gordon Harsh and Charlemae Hill Rollins must be mentioned too—Harsh, the first Black librarian in the CPL system, assembled the largest African American history and literature collection in the Midwest and put together a talented staff of Black women, including Rollins, who'd become an influential children’s librarian.

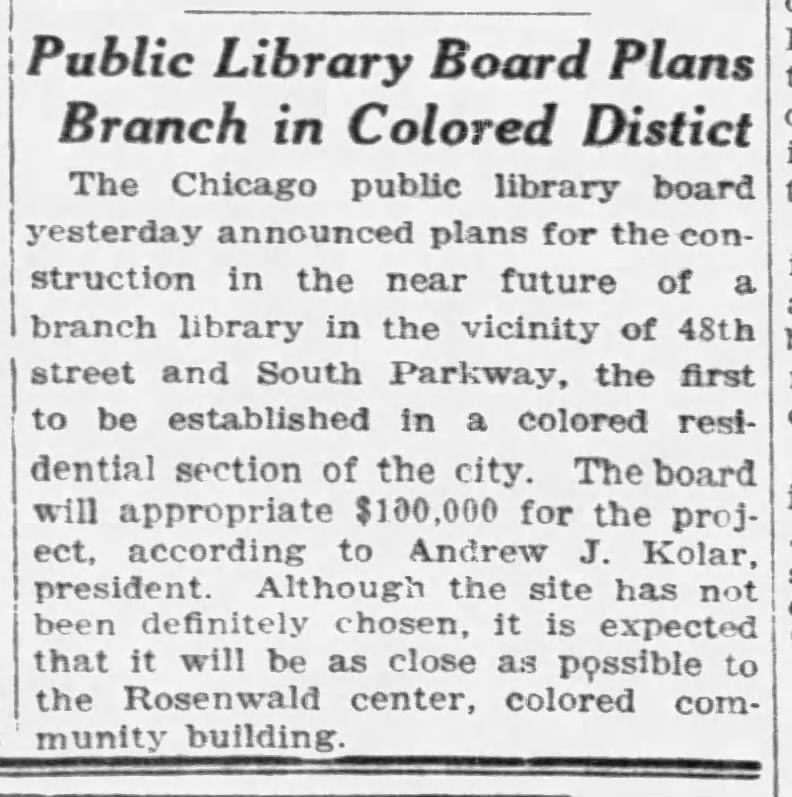

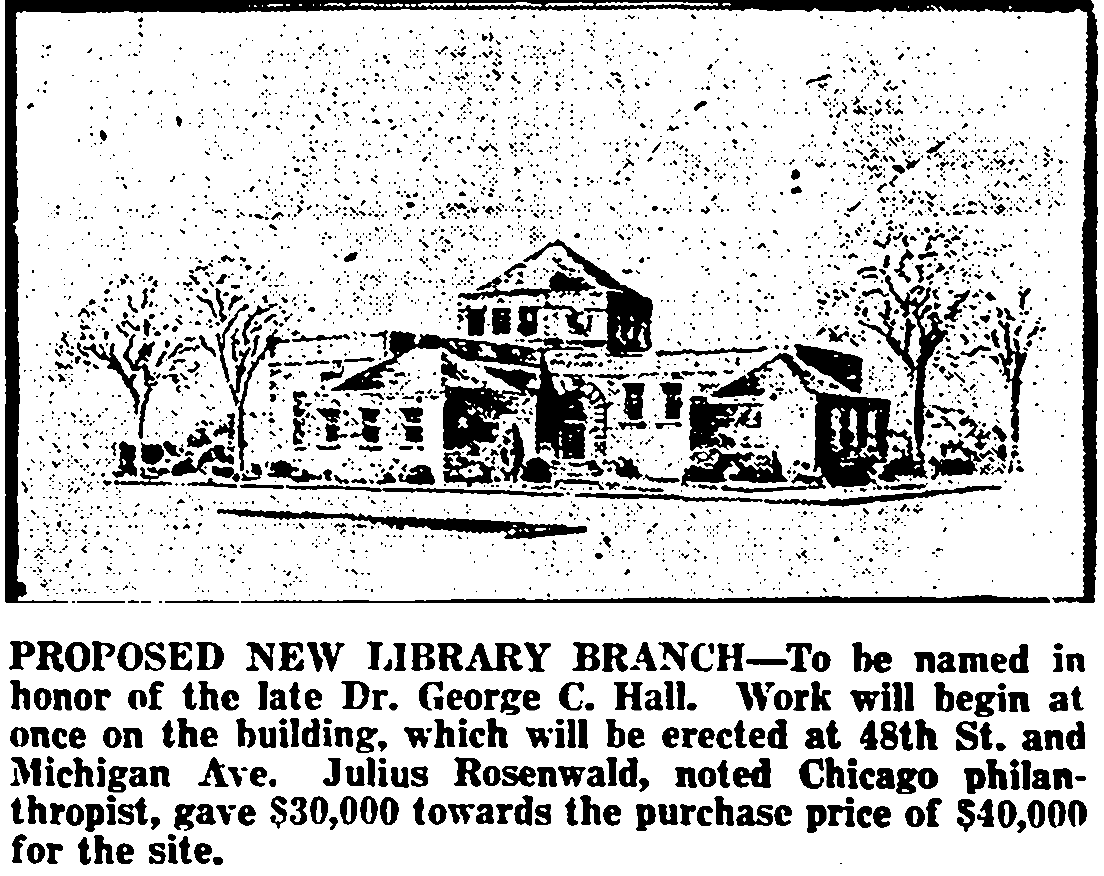

1929 Chicago Tribune article on the new library in Bronzeville and a 1929 Chicago Defender article where George Cleveland Hall pushes back against the idea that it was only a library for Black people

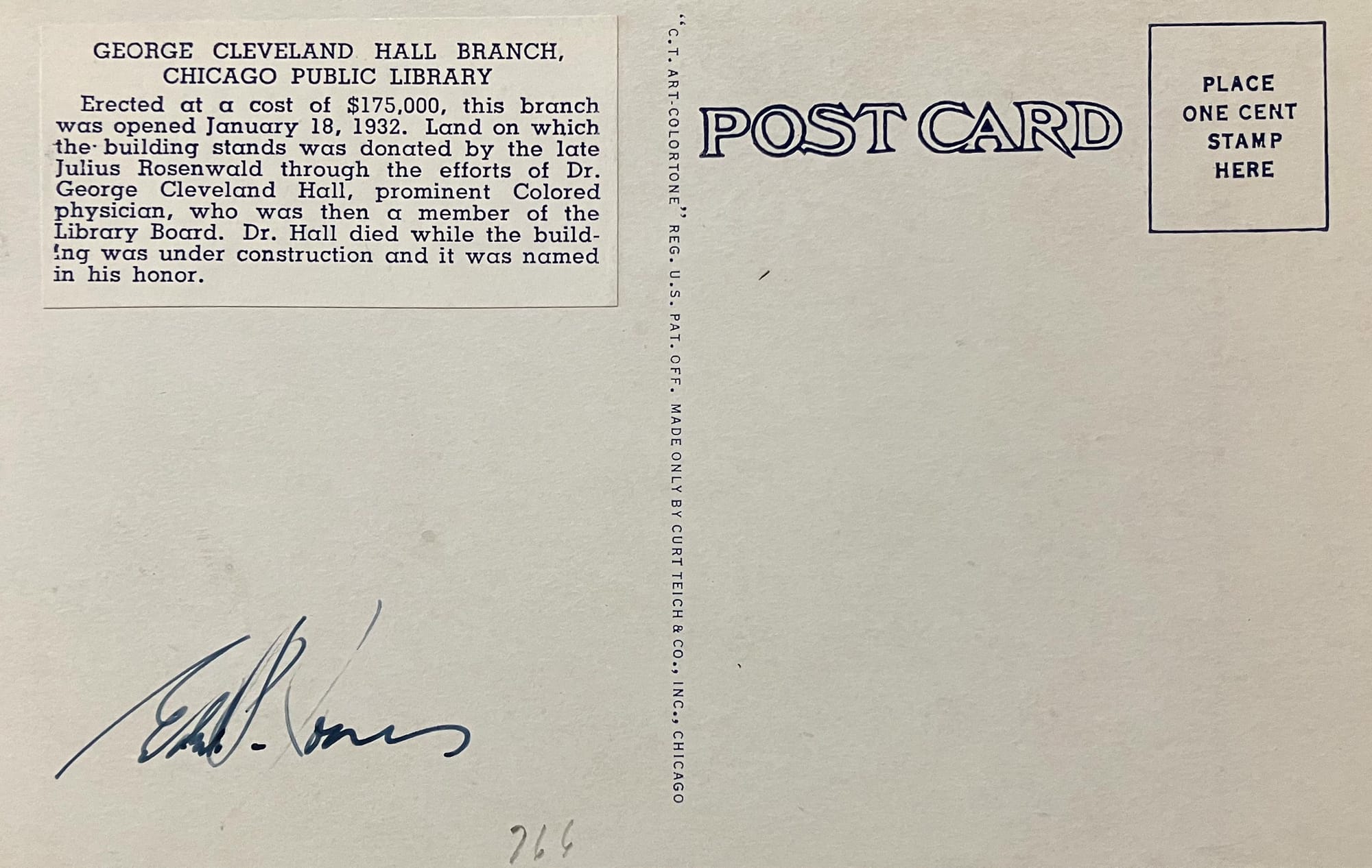

The library’s namesake, George Cleveland Hall, fought like hell to bring a library to Bronzeville. Hall was a surgeon, a leader of the Chicago Urban League, and a bigwig at Provident Hospital, the first Black-owned and managed hospital in the US. Hall embarked on a relentless multi-year campaign to get Bronzeville a library, first securing a seat on the library board, then convincing Julius Rosenwald to donate the land for it. Hall succeeded, then died before it was built—which made the name of the library a no-brainer.

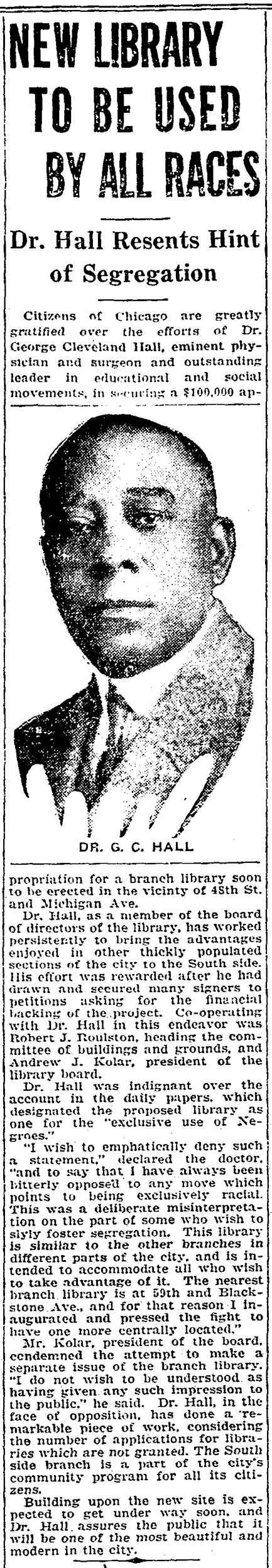

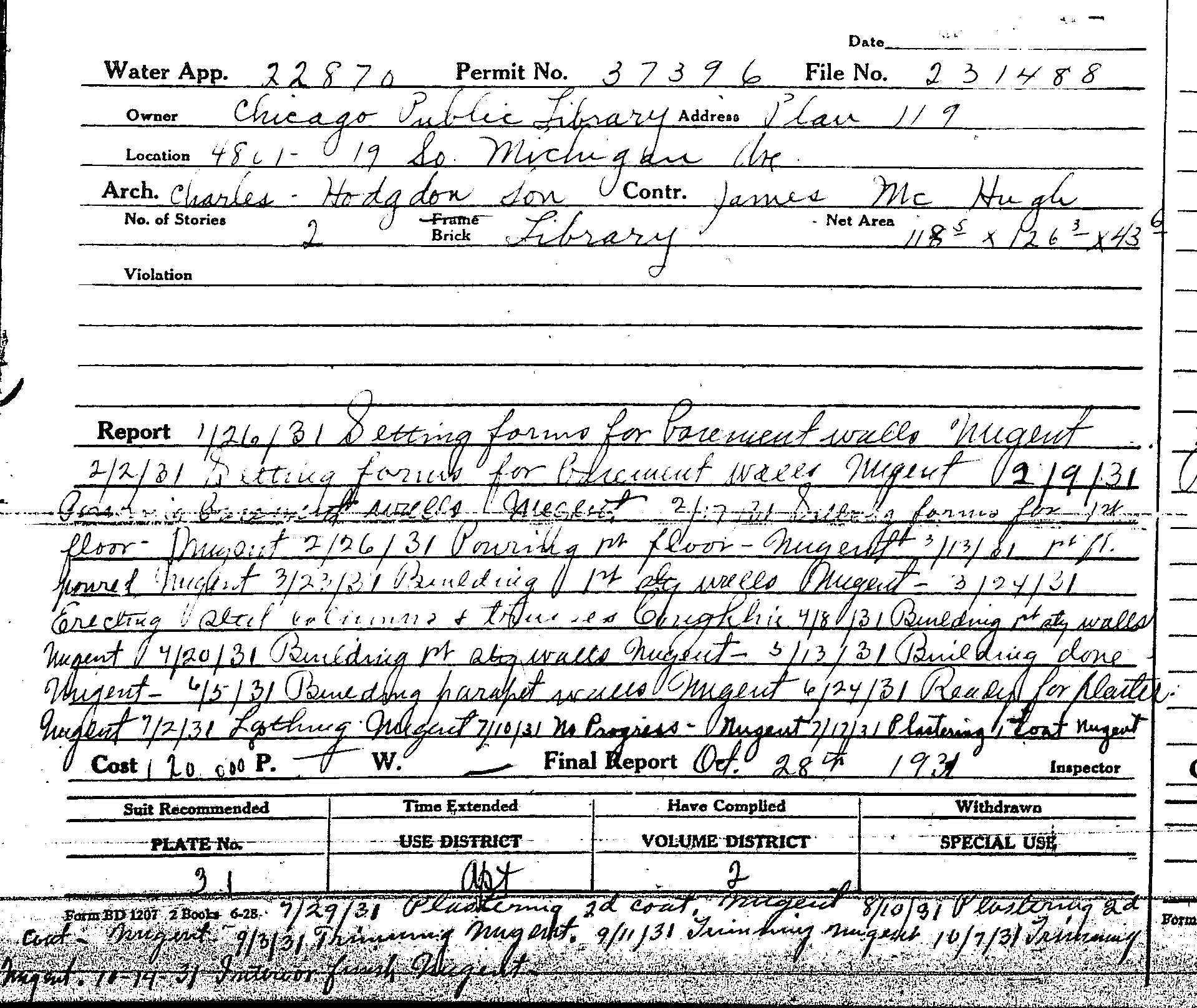

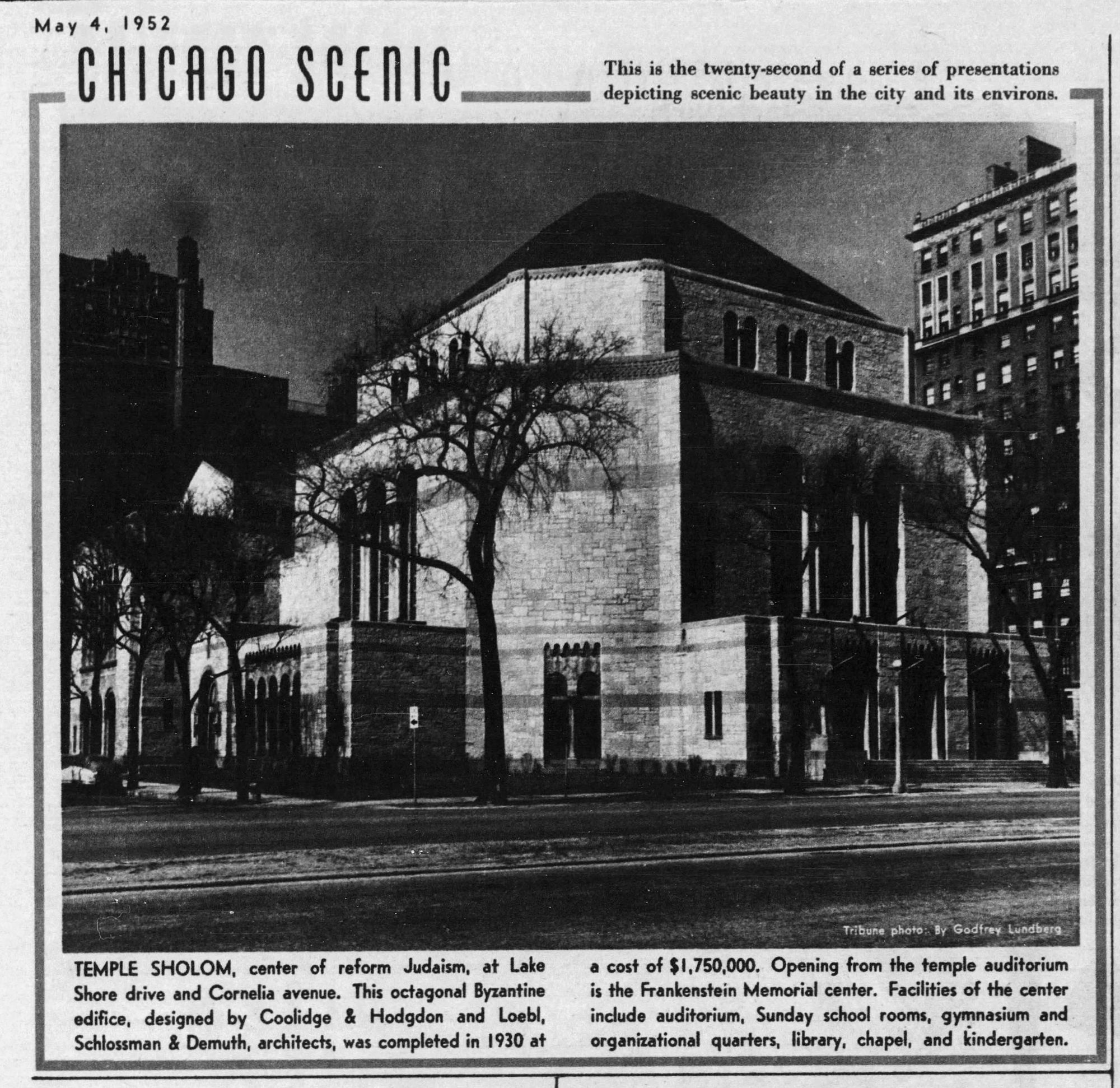

1930 sketch of the library in the Chicago Defender; 1931 building permit; another octagonal Charles Hogdgon-designed building, Temple Sholom in Lakeview

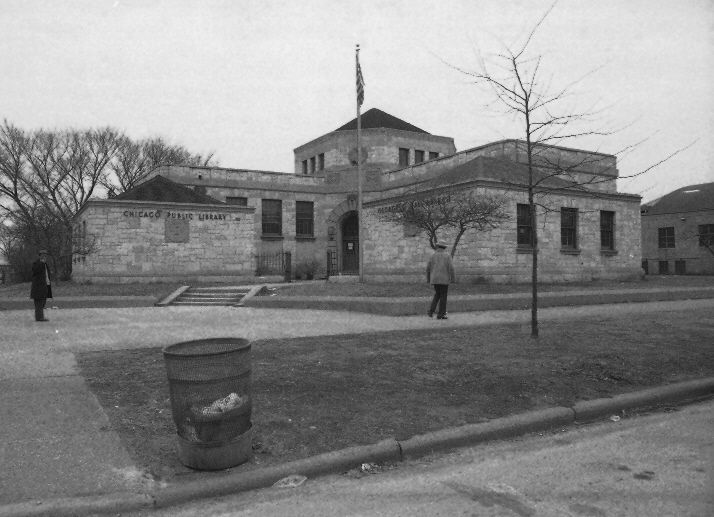

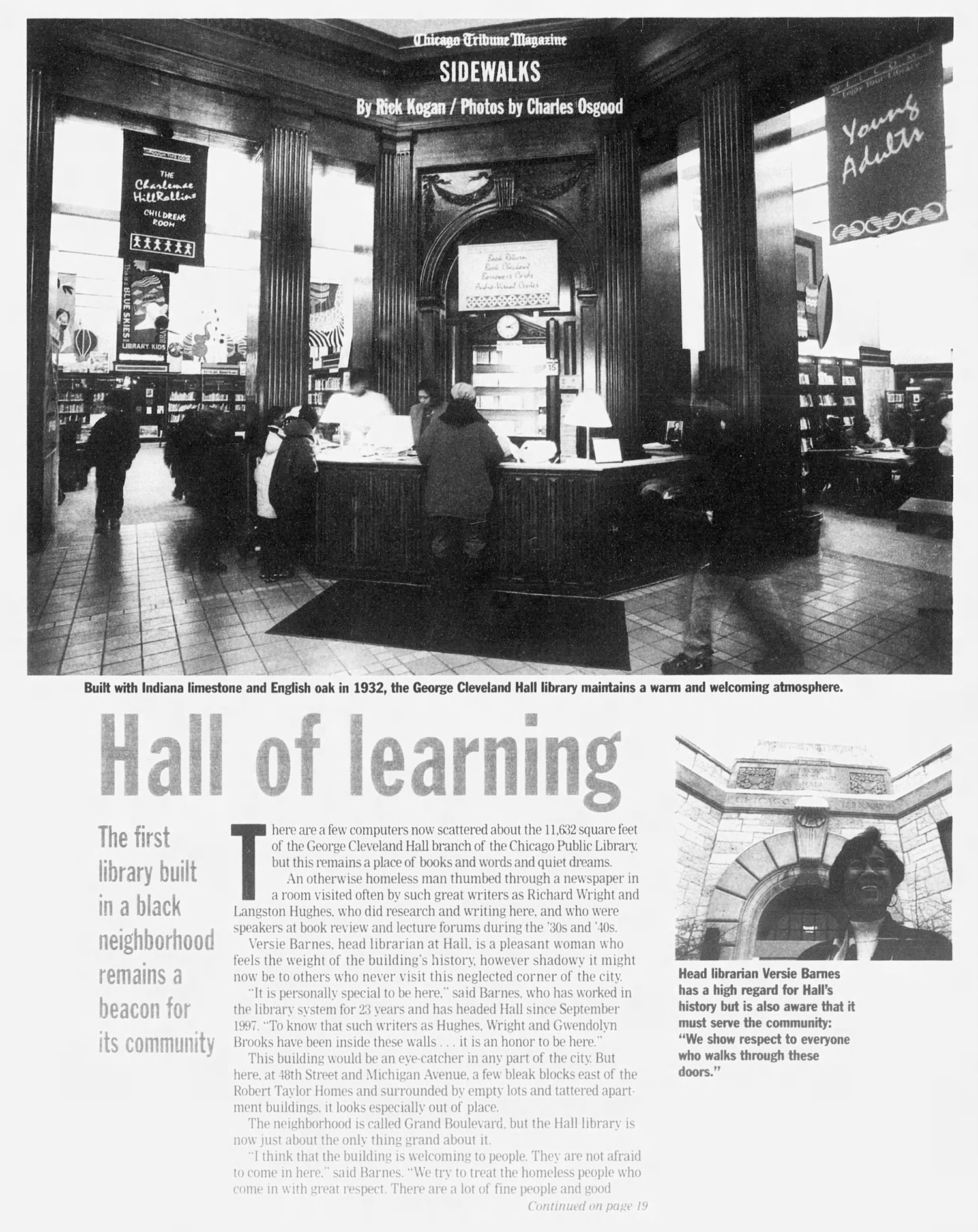

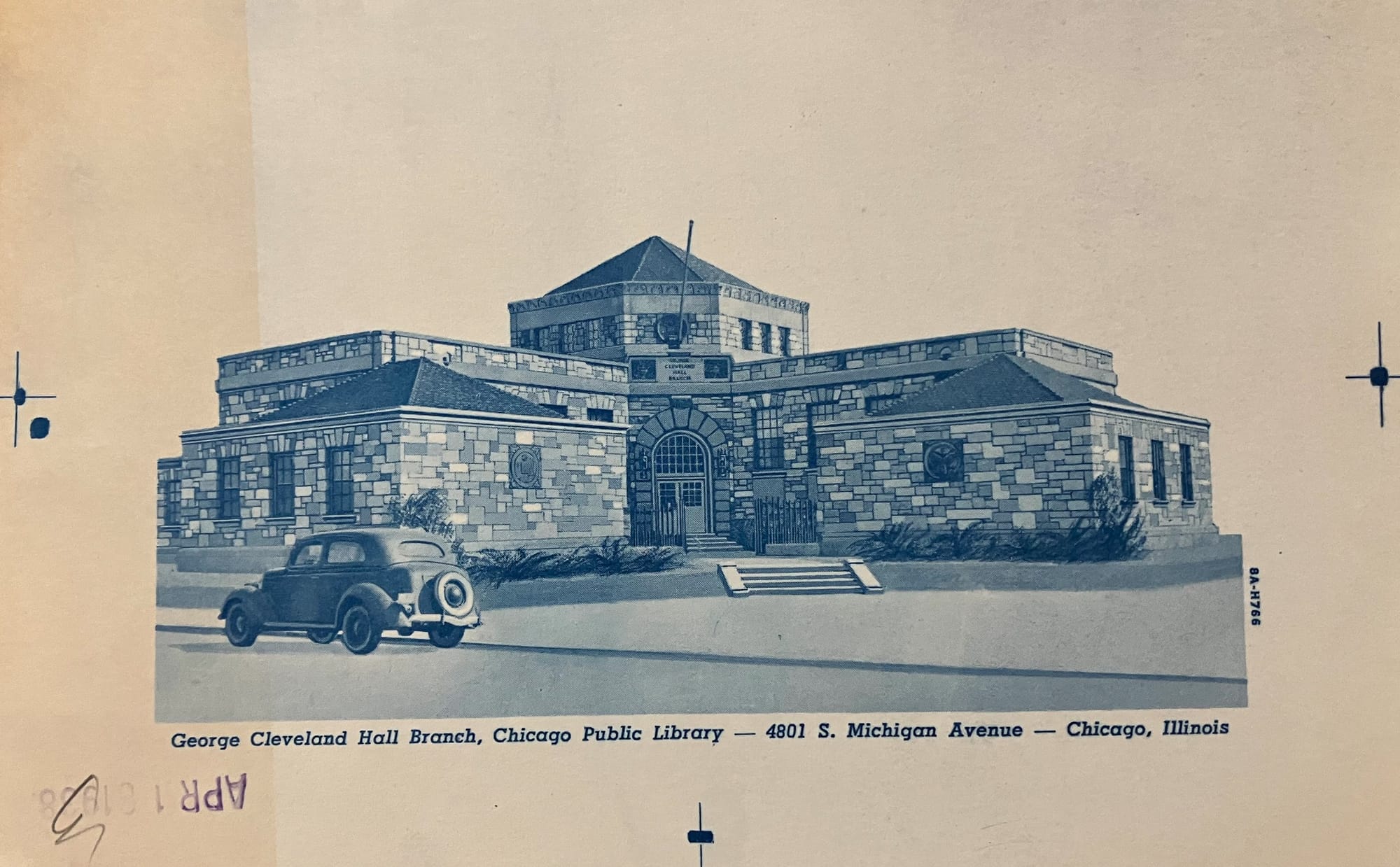

Designed by Charles Hodgdon & Son, the handsome neoclassical library with the quirky octagon on top opened in 1932. Hodgdon & Son was the successor firm to Coolidge & Hodgdon, itself the successor to Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge - the firm who designed the Art Institute.

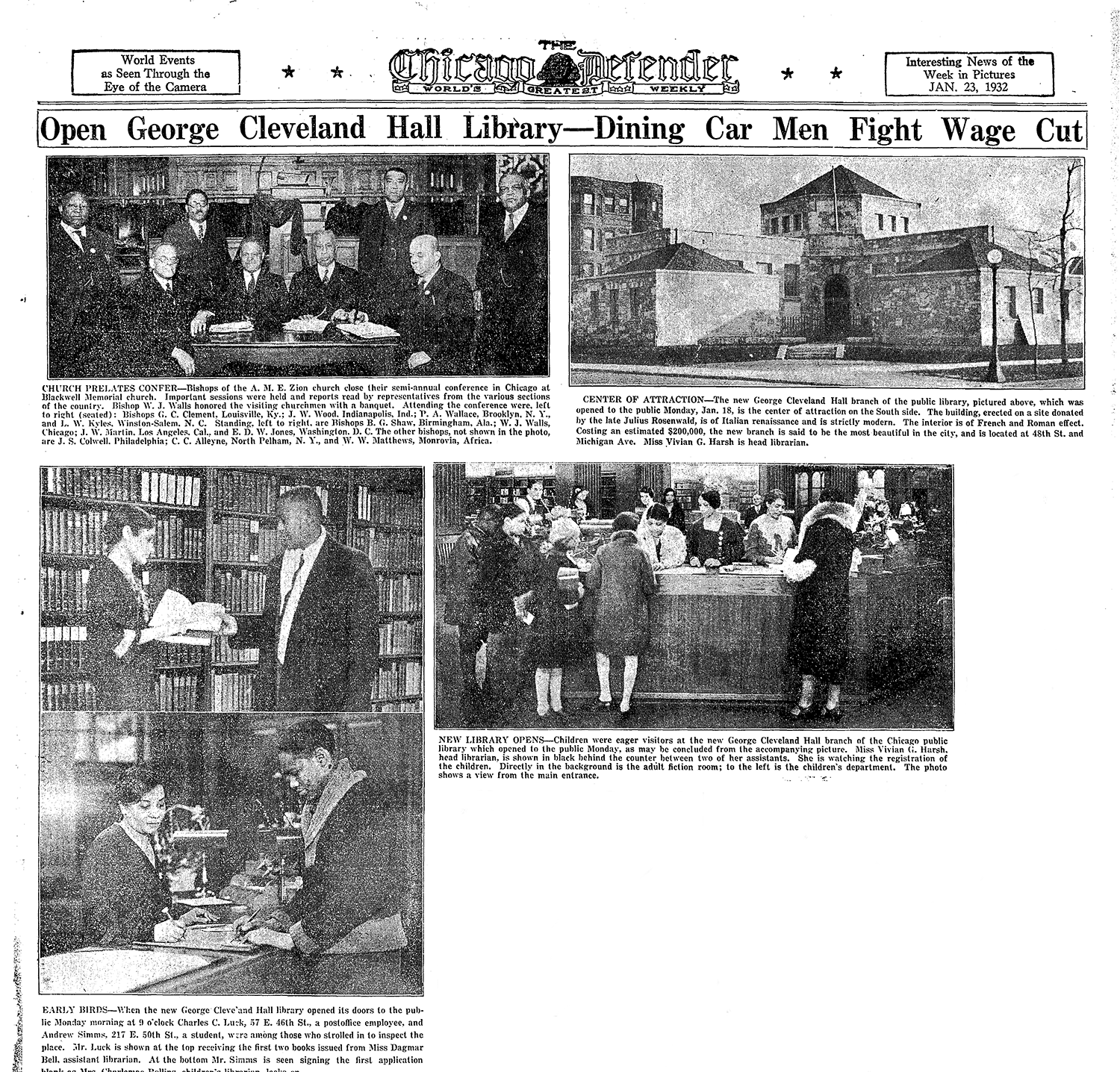

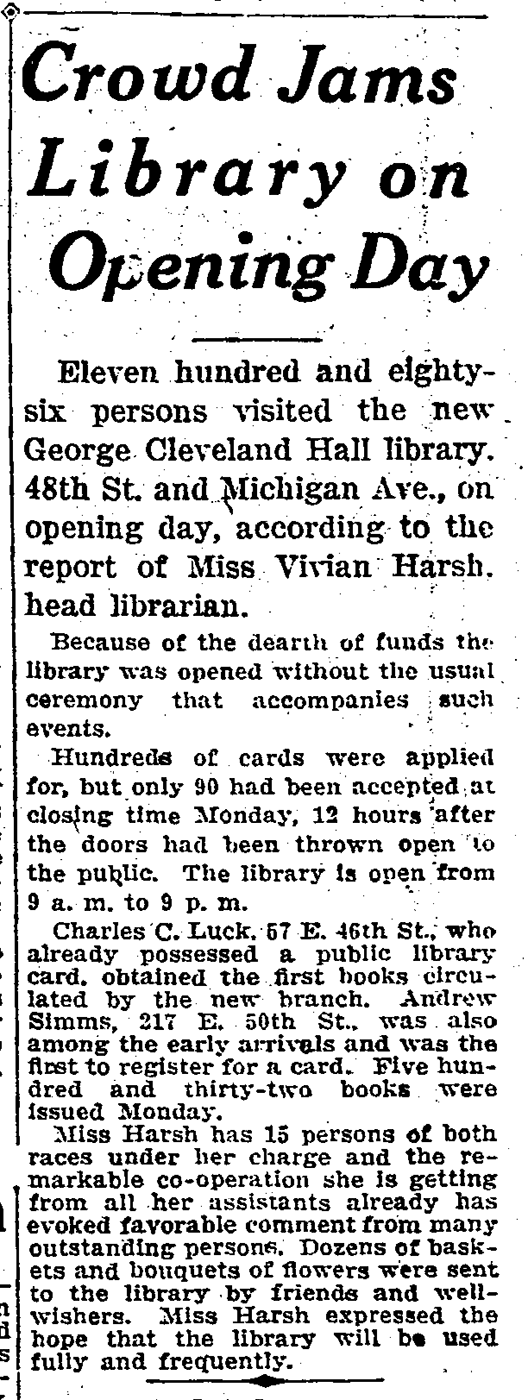

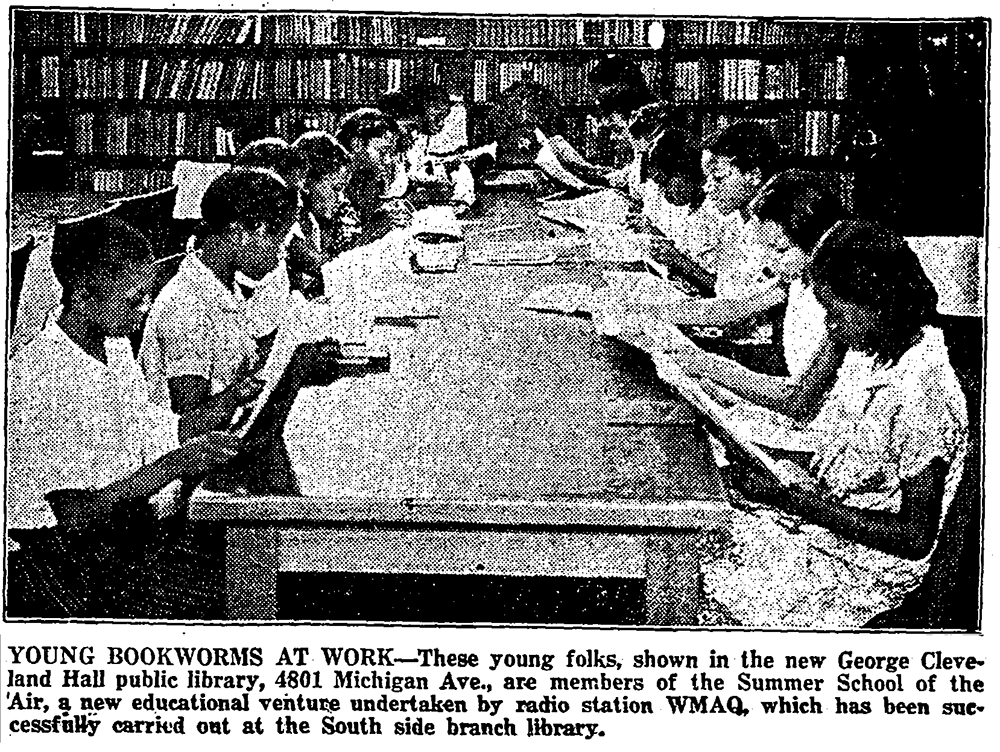

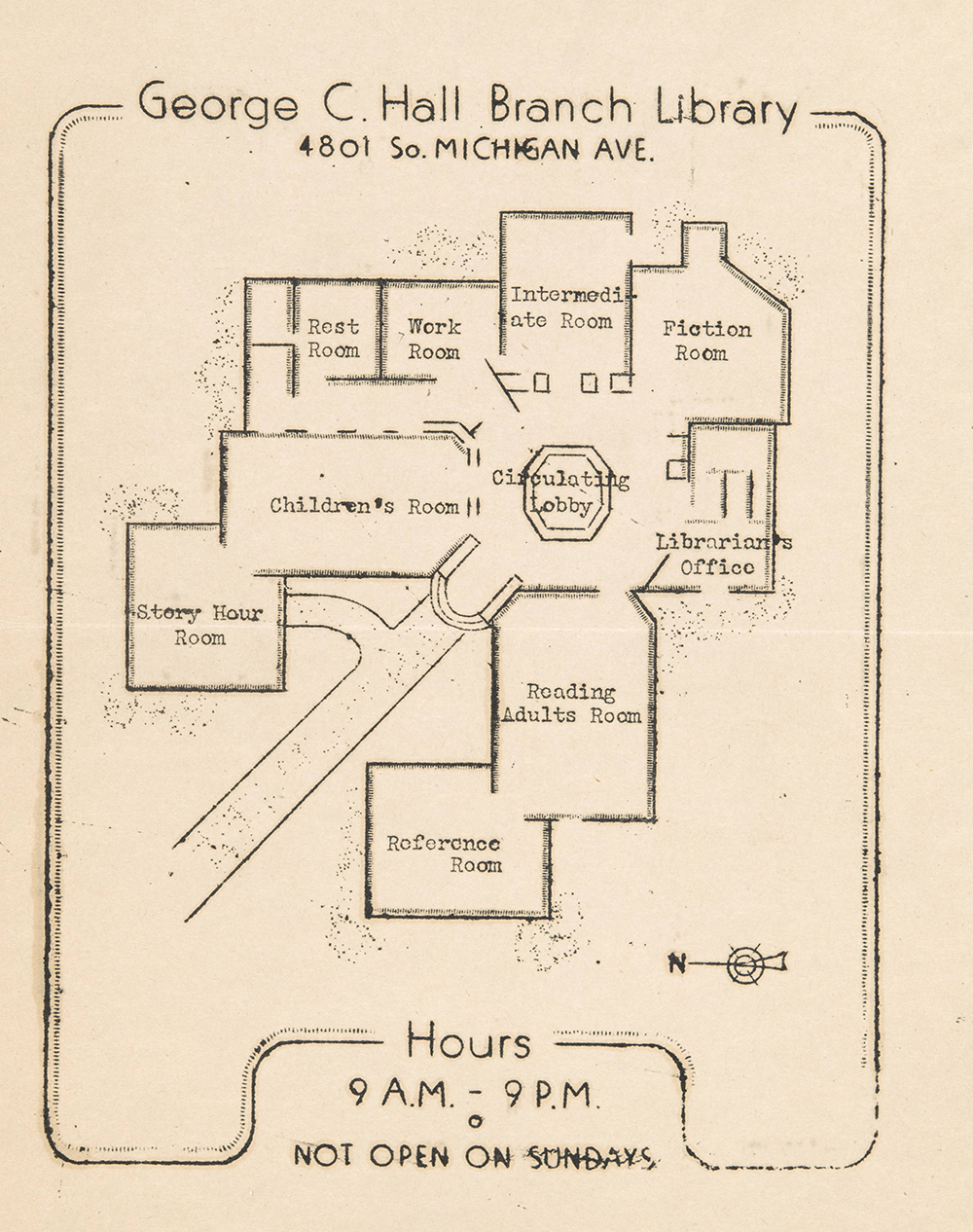

1932 Chicago Defender articles on the opening of the new library; a floor plan and a photo of the library via the CPL George Cleveland Hall Branch Archives

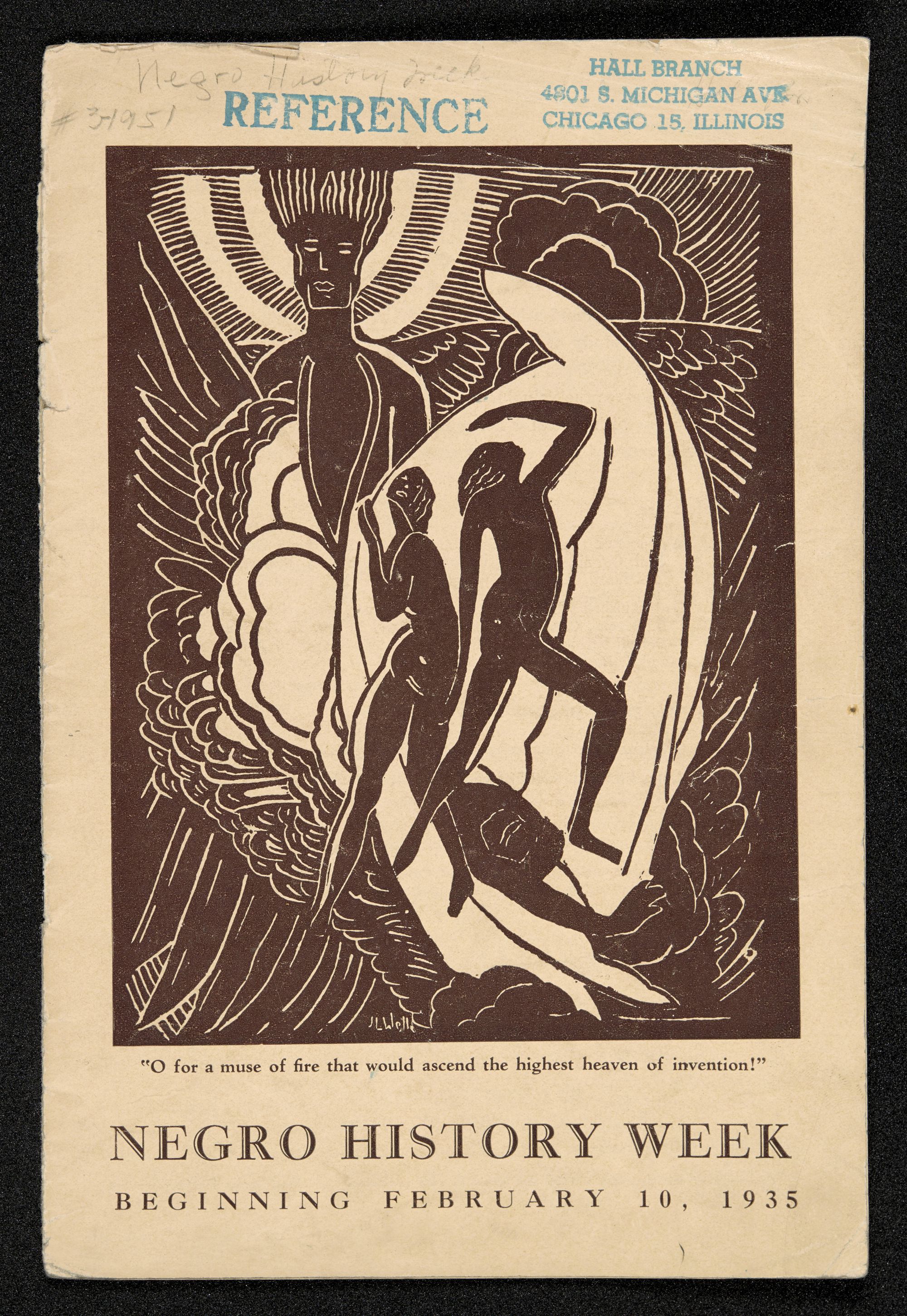

Pent up demand in densely-populated Bronzeville meant the library immediately became a key neighborhood institution, and librarian Vivian Harsh assembled a talented staff of Black women to run it: Arlene Morrell, Esther Wilson, Edith Allman Gans, Ellyn Askins, Nina Roberts, Marian Hadley, Dagmar Bell, Consuelo Young, Doris Evans Saunders, and Bessie Benson. The Hall Branch quickly became an engine for the Chicago Black Renaissance in the 1930s.

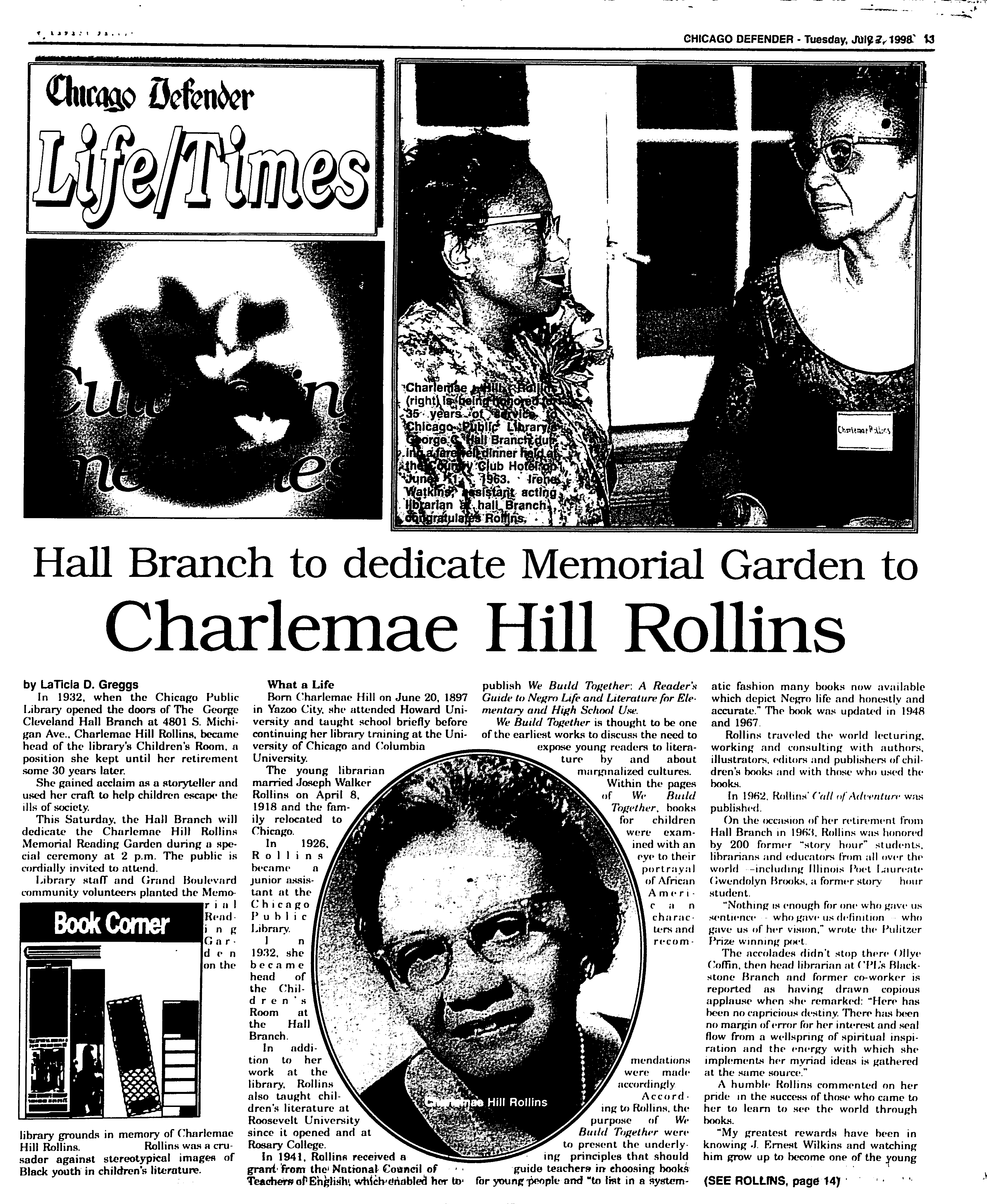

1960 Chicago Defender article on Charlemae Hill Rollins getting an award; 1996 article on a garden dedicated to Hill Rollins

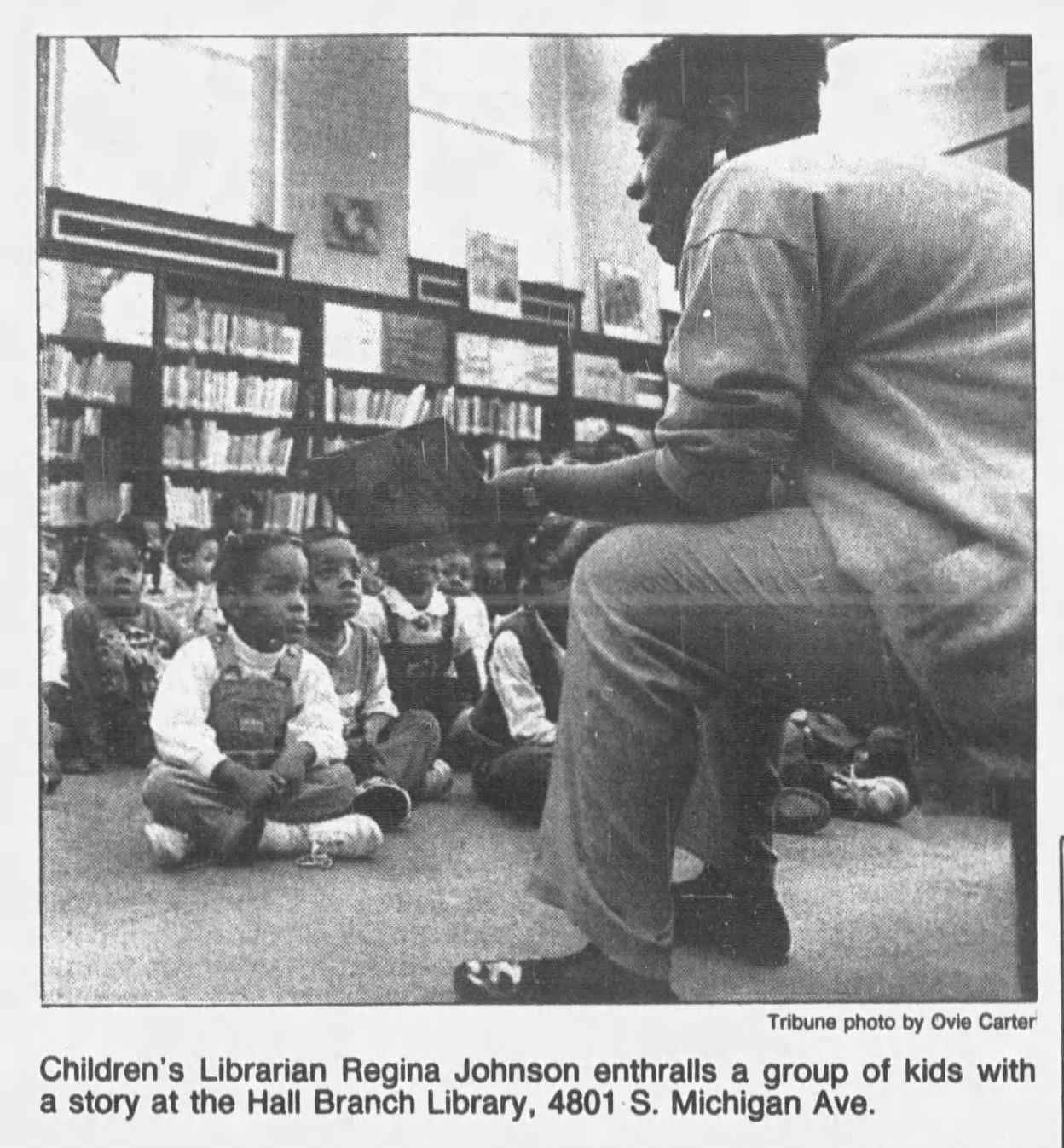

Vivian Harsh also hired Charlemae Hill Rollins, who'd become a legendary children's librarian. Mayor Harold Washington’s favorite librarian when he was a child, Hill Rollins made a point to build out a children's collection that positively and accurately portrayed Black life and that kids could identify with.

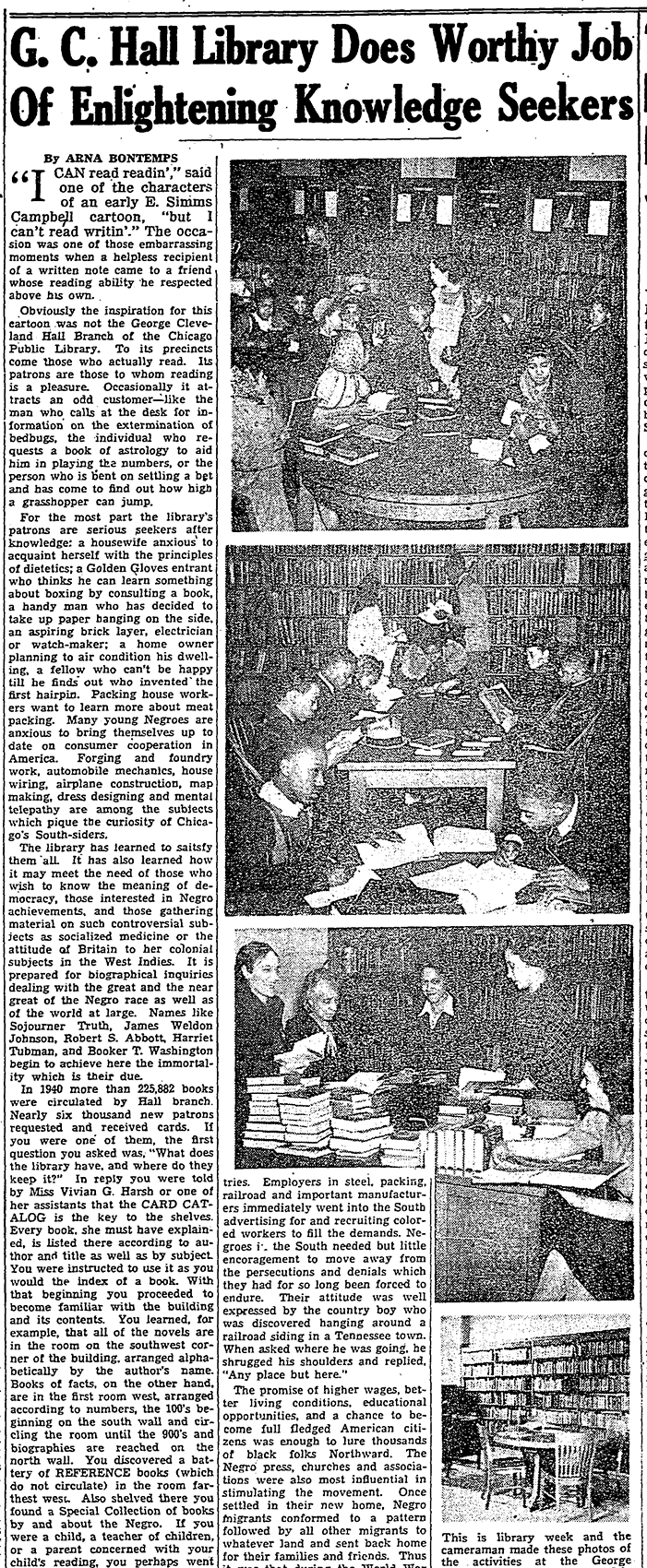

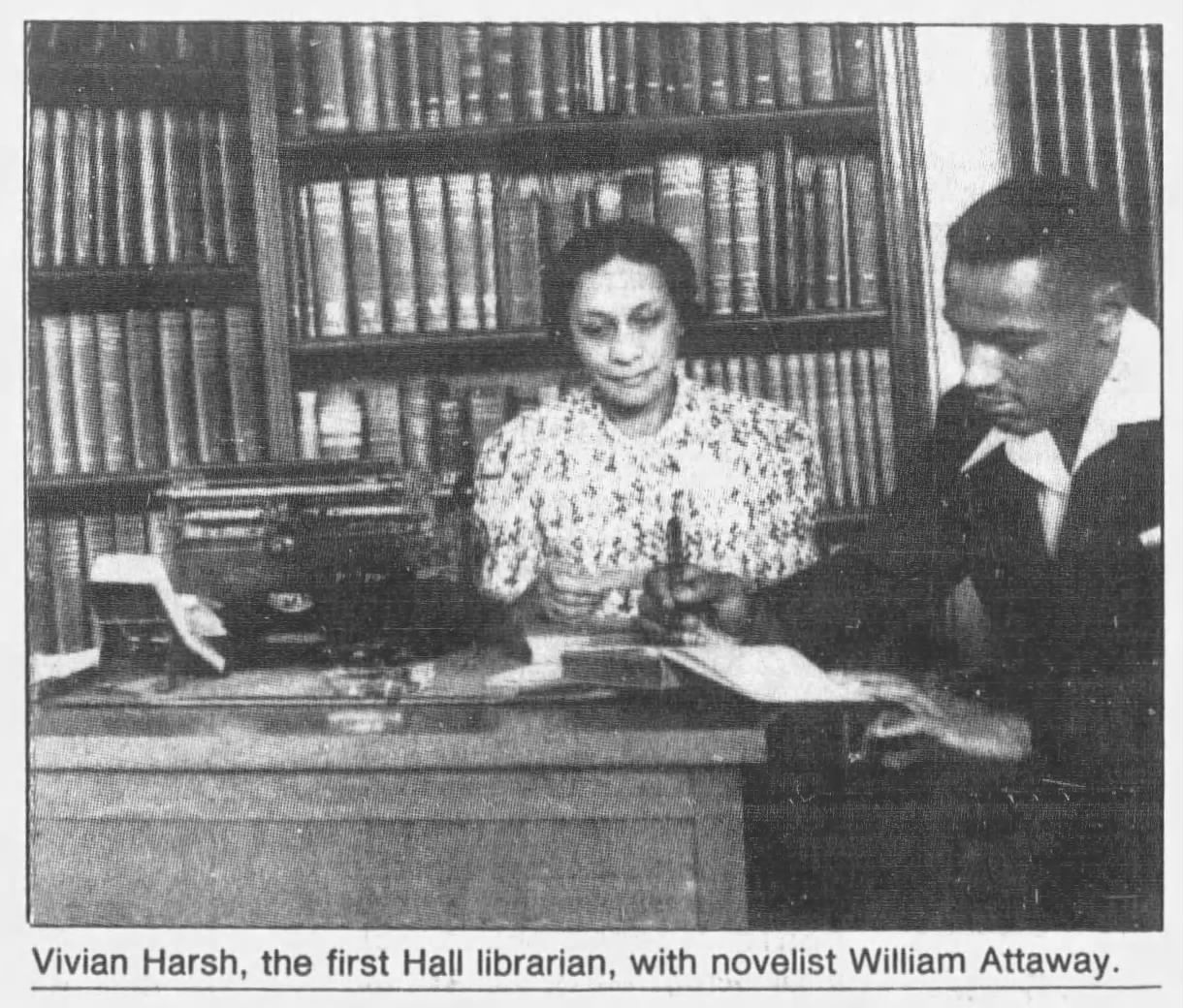

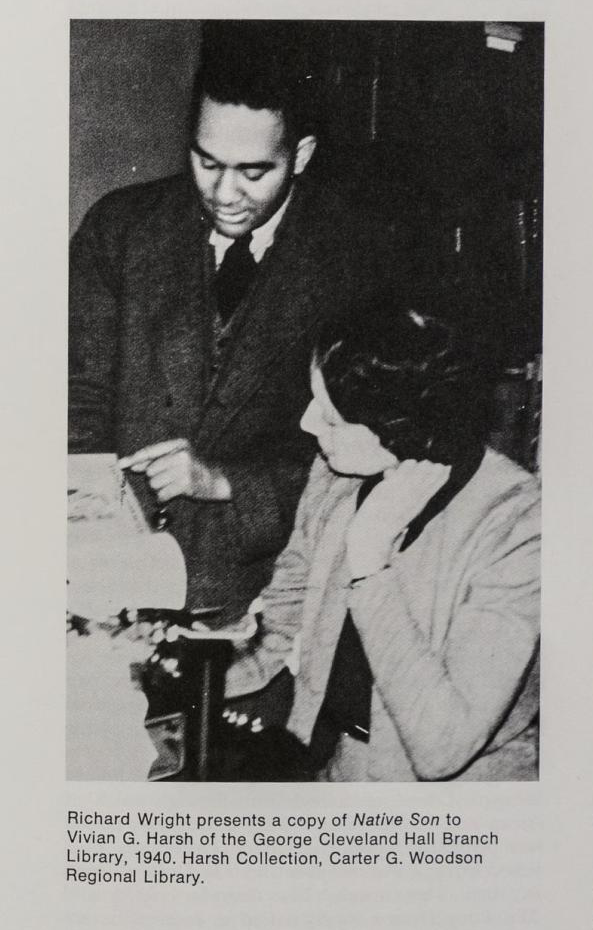

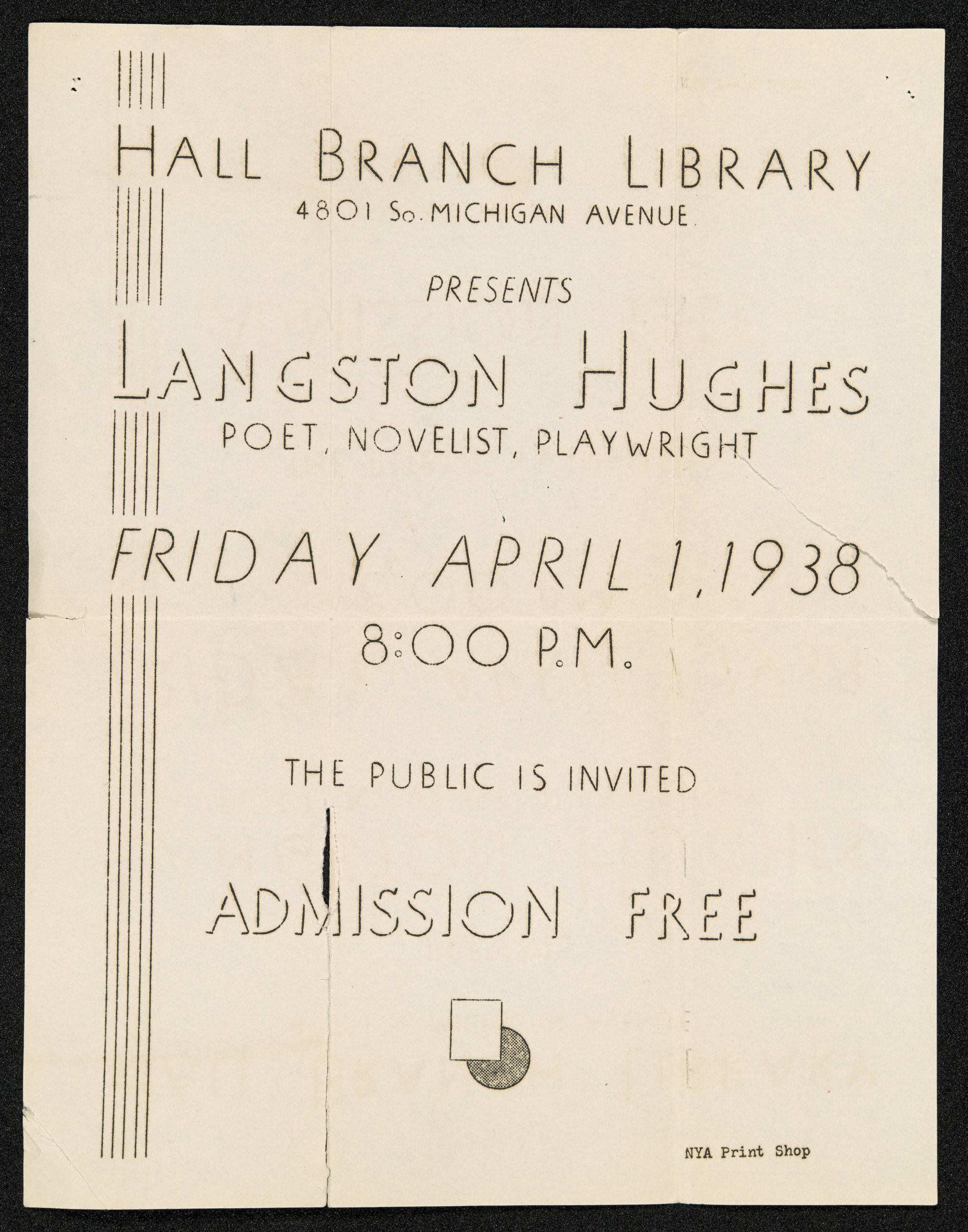

1941 Arna Bontemps article on the library; Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes at the library in 1949; Vivian Harsh with William Attaway; Richard Wright presents a copy of Native Son to Vivian Harsh; flyer for a 1938 Langston Hughes event via the CPL George Cleveland Hall Branch Archives

Harsh successfully dedicated her career to creating space for Black history and literature in the library system. The library’s Book Review and Lecture Forum hosted speakers like Langston Hughes, and Harsh’s research collection was a vital resource for writers like Richard Wright, Arna Bontemps, and William Attaway.

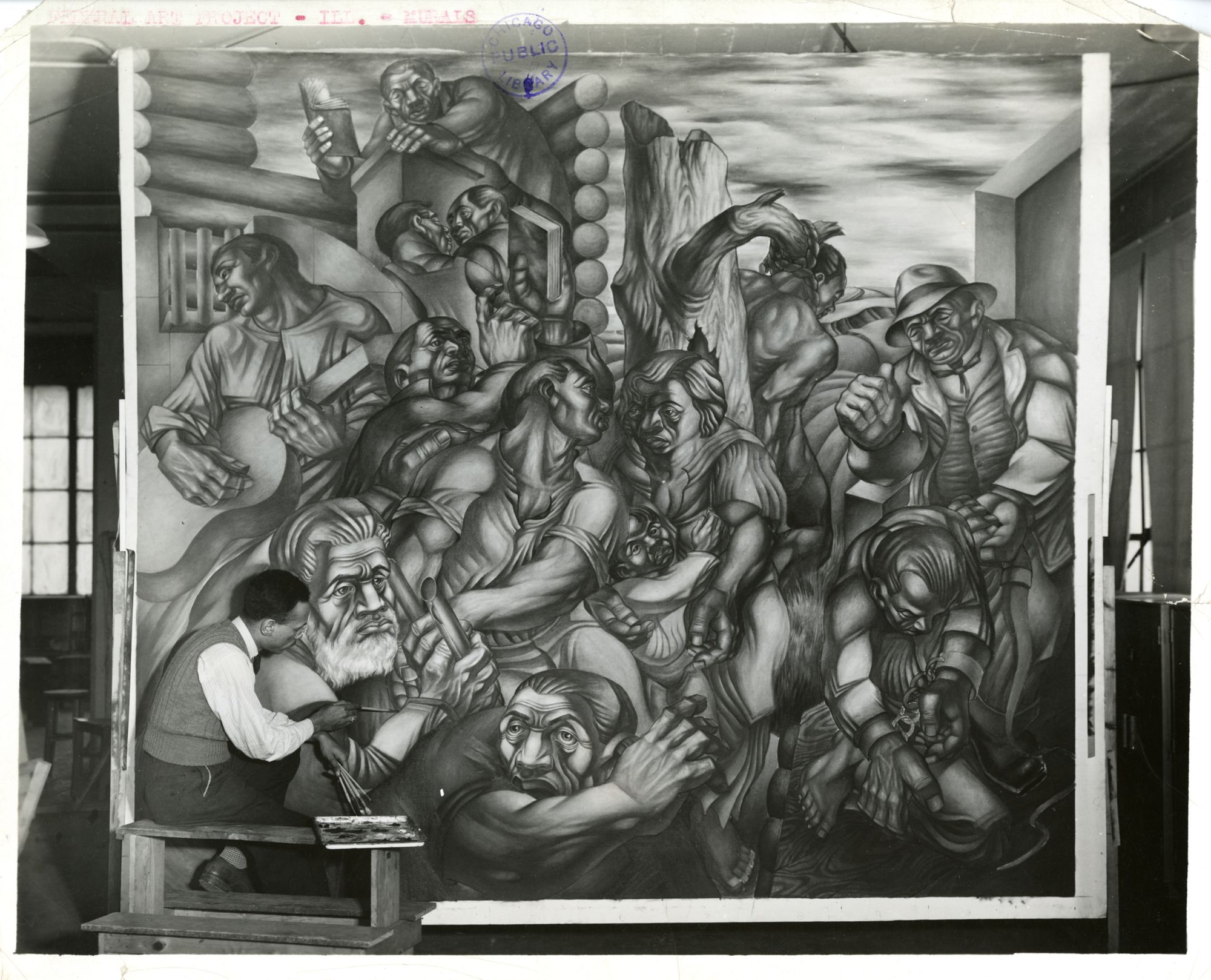

Charles White working on the WPA mural meant for the George Cleveland Hall Branch Library via the Art Institute of Chicago; 1942 Chicago Defender article that mentions Charles White working on a mural for the library

That influenced extended to the arts as well—Chicago artist Charles White credits his discovery of Alain Locke's The New Negro at the Hall Branch as a key point in his development as an artist. Bringing things full circle, he was commissioned to paint a WPA Federal Art Project mural for the library in 1940-1941...but the project was canceled and the partially finished mural lost.

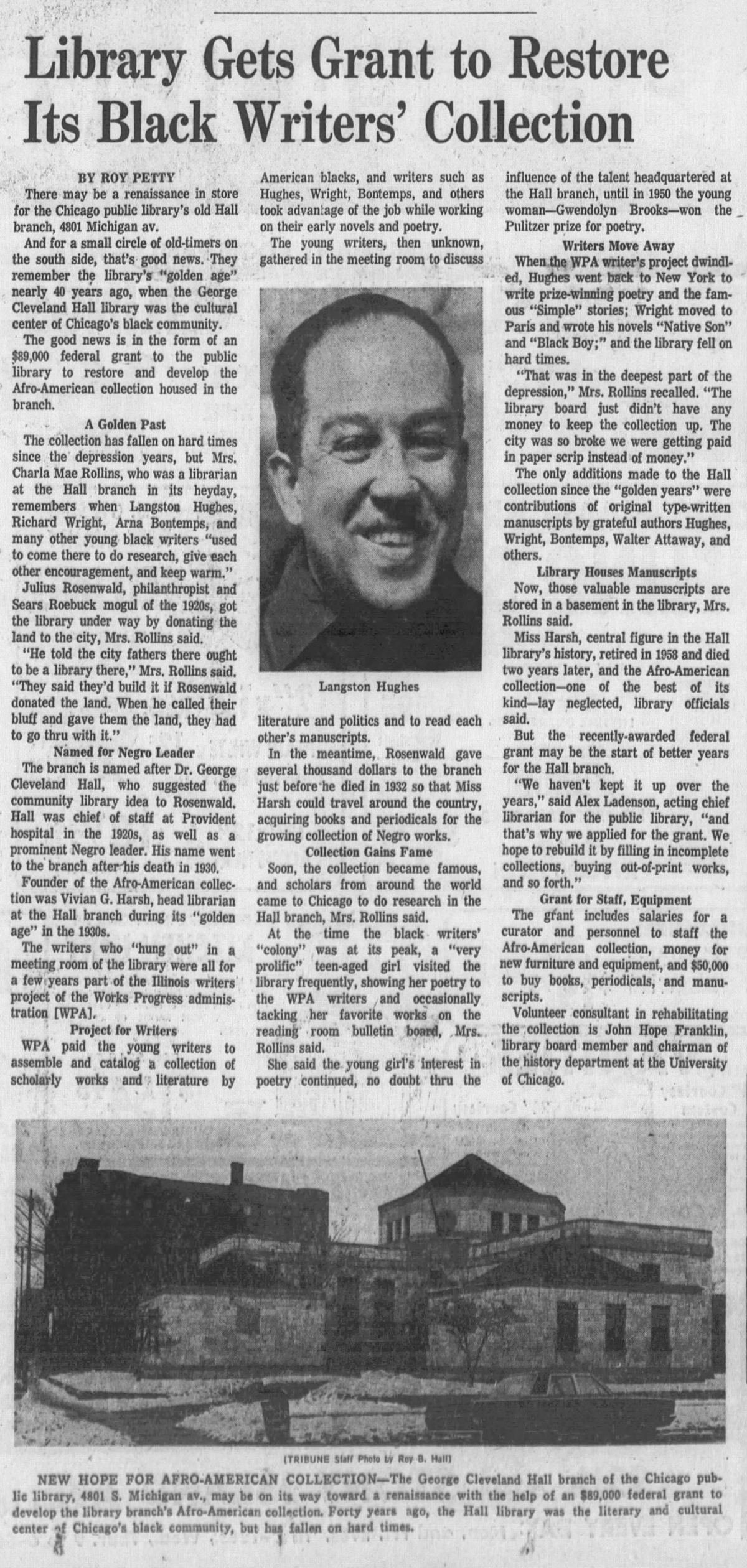

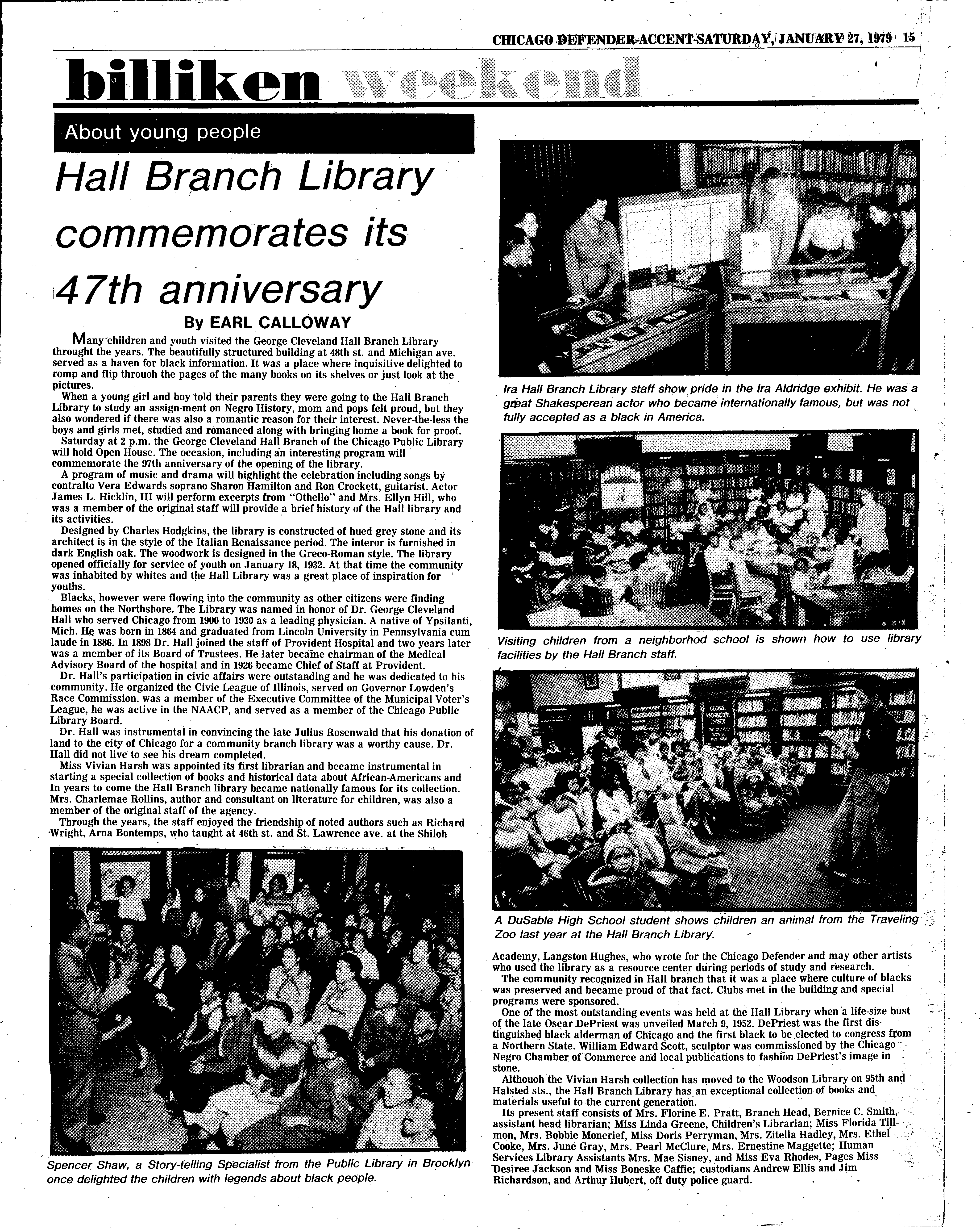

1970 Chicago Tribune article on the library getting a grant to restore the Harsh Collection; photo via the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency; 1979 Chicago Defender article on the library commemorating its 47th anniversary

Once one of the most densely populated neighborhoods in the US (...because racist housing policies prevented Black Chicagoans from living anywhere else), Bronzeville emptied out in the 1970s (as a few of those policies disappeared, replaced with racist disinvestment instead). The Chicago Public Library moved the Harsh Research Collection to the Carter Woodson Branch Library in 1975—kind of a slap in the face to a struggling Bronzeville.

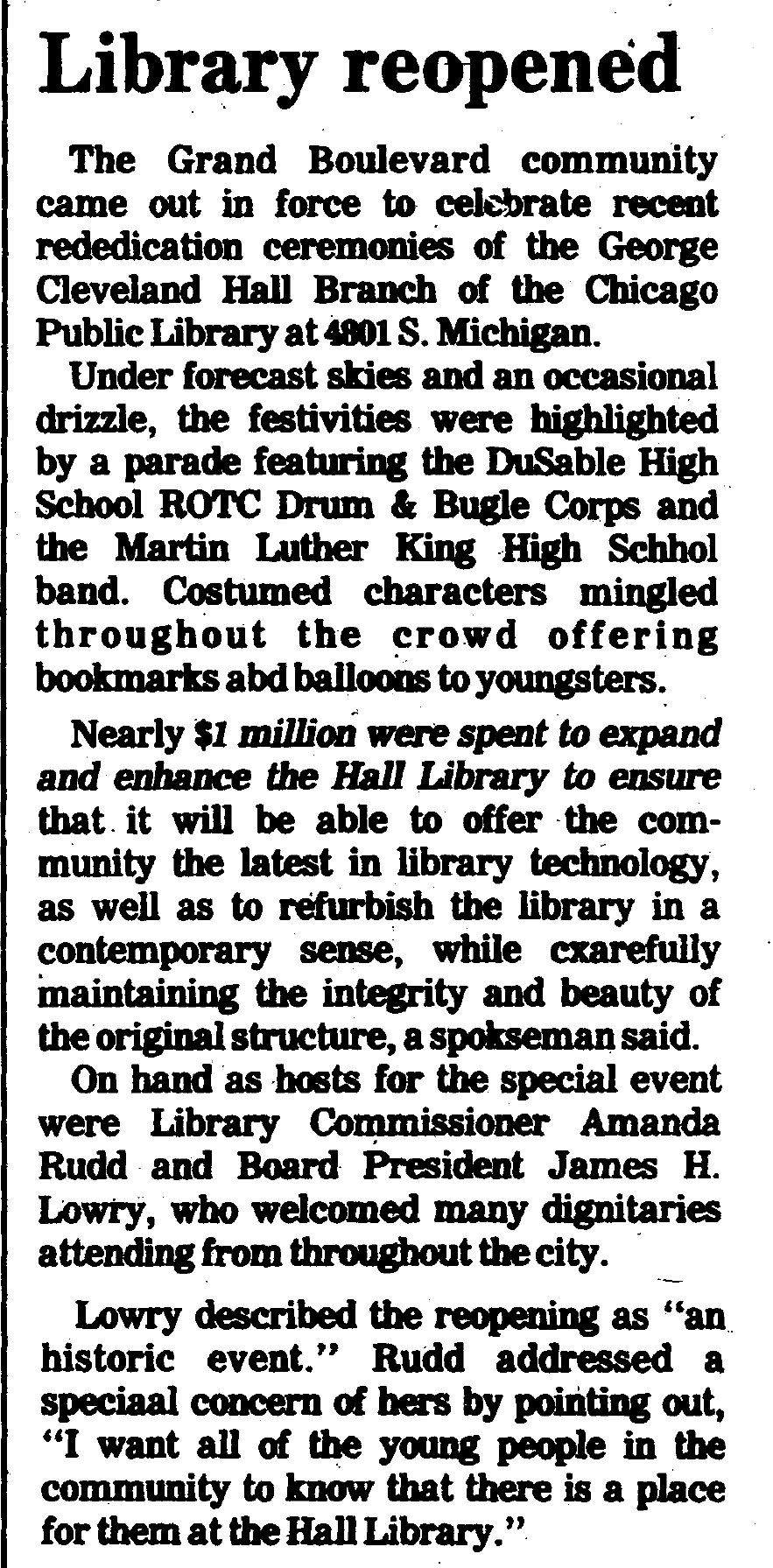

1984 Chicago Defender article on the library opening after renovations; 1996 article on the renovation building housing the Harsh Collection at the Carter Woodson Regional Library

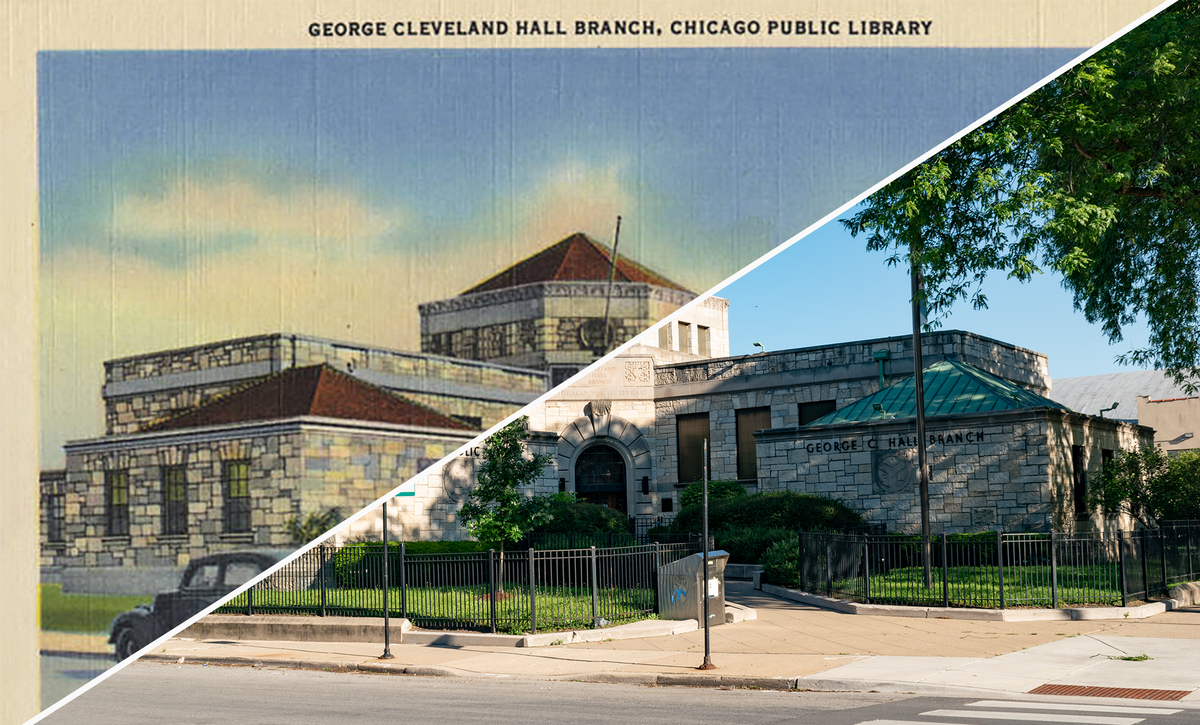

The George Cleveland Hall Branch Library was renovated in the 1980s and reopened in 1984. The Harsh Research Collection—still a vital archive today—received an expanded home at the Carter Woodson Branch in 1996. Today Bronzeville is bustling again and 90 years later the Hall Branch remains a neighborhood institution. The building was designated a city landmark in 2009 as part of the Black Renaissance Literary Movement district.

1999 Tribune article on the library; 1990 photo from a Tribune article

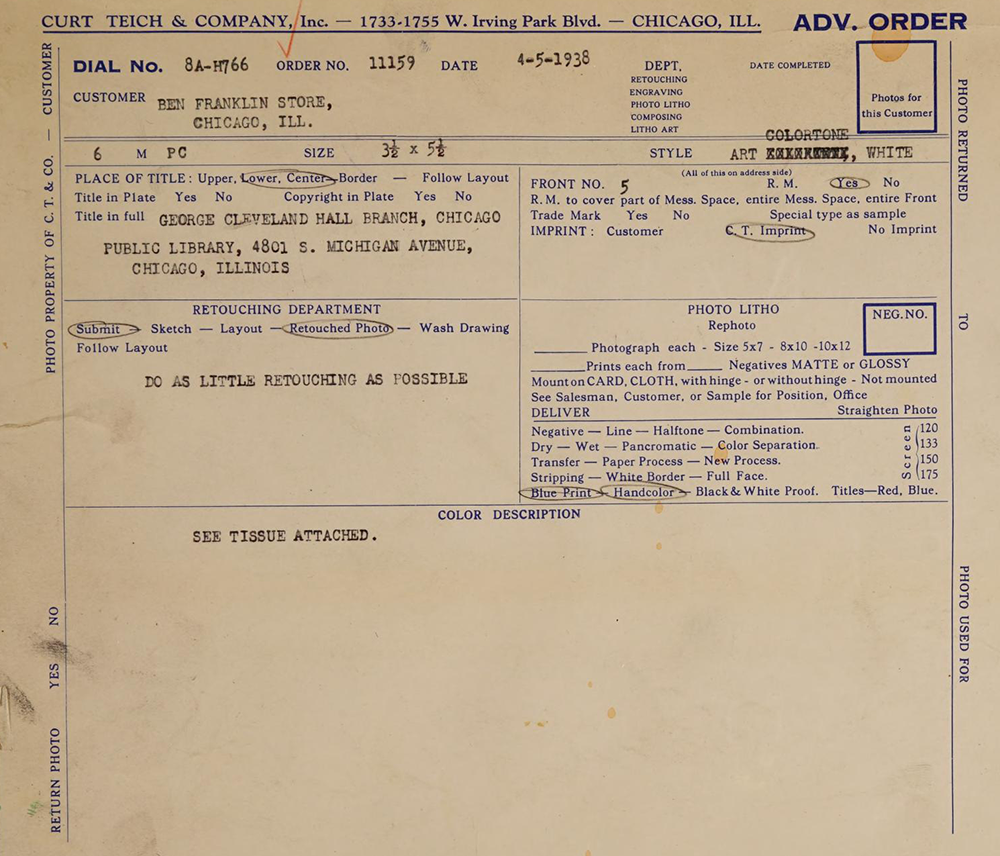

Production Files

Further reading:

- The City of Chicago Landmark Designation Report

- Highly informative blog by S.M. O'Connor about the library

- Two articles on what the George Cleveland Hall Branch meant to Charles White, one from the Chicago Public Library and one from the Art Institute of Chicago

- George Cleveland Hall Branch Digital Collection at the Chicago Public Library

- Cultural Record Keepers: Vivian G. Harsh Collection of Afro-American History and Literature, Carter G. Woodson Regional Library, Chicago Public Library

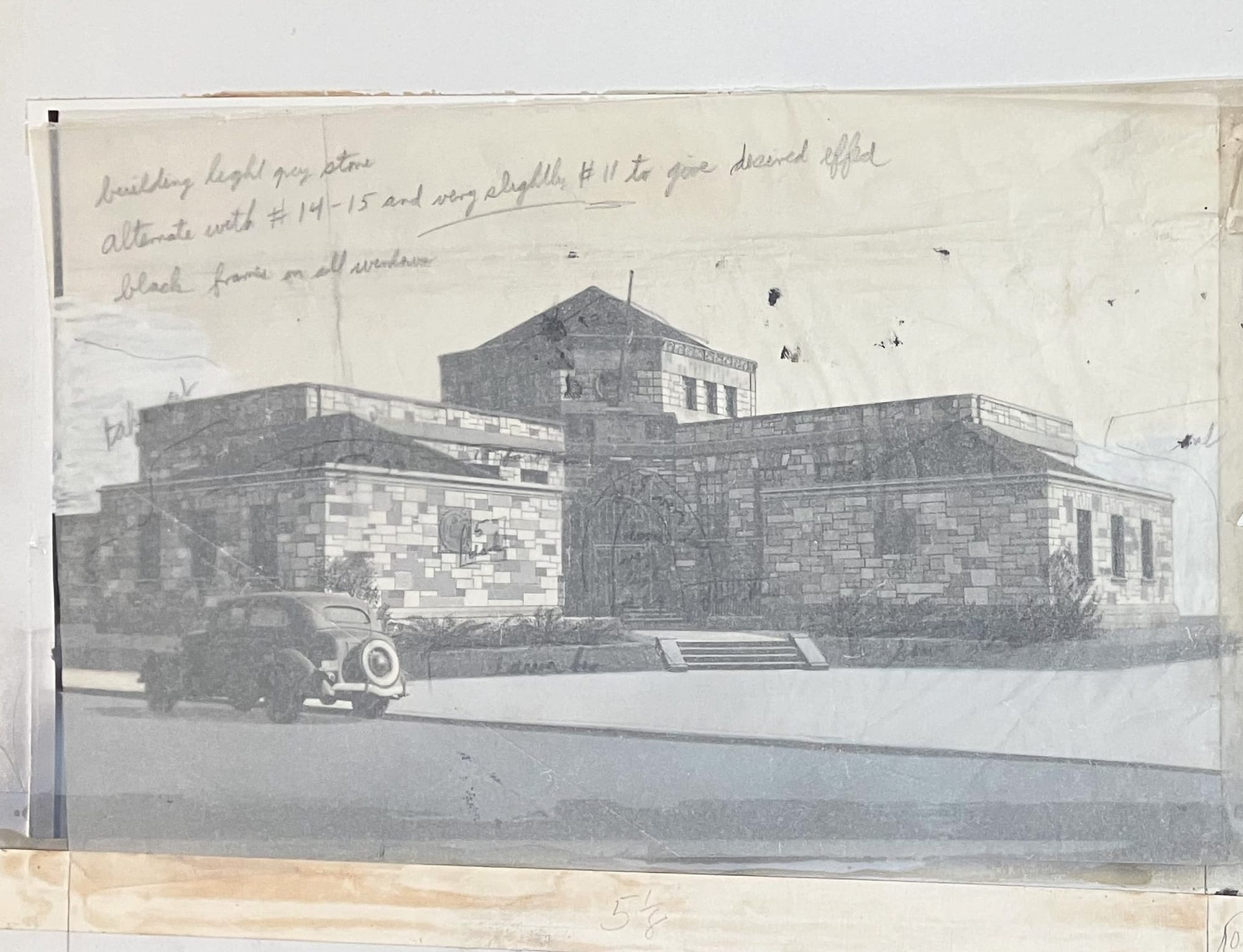

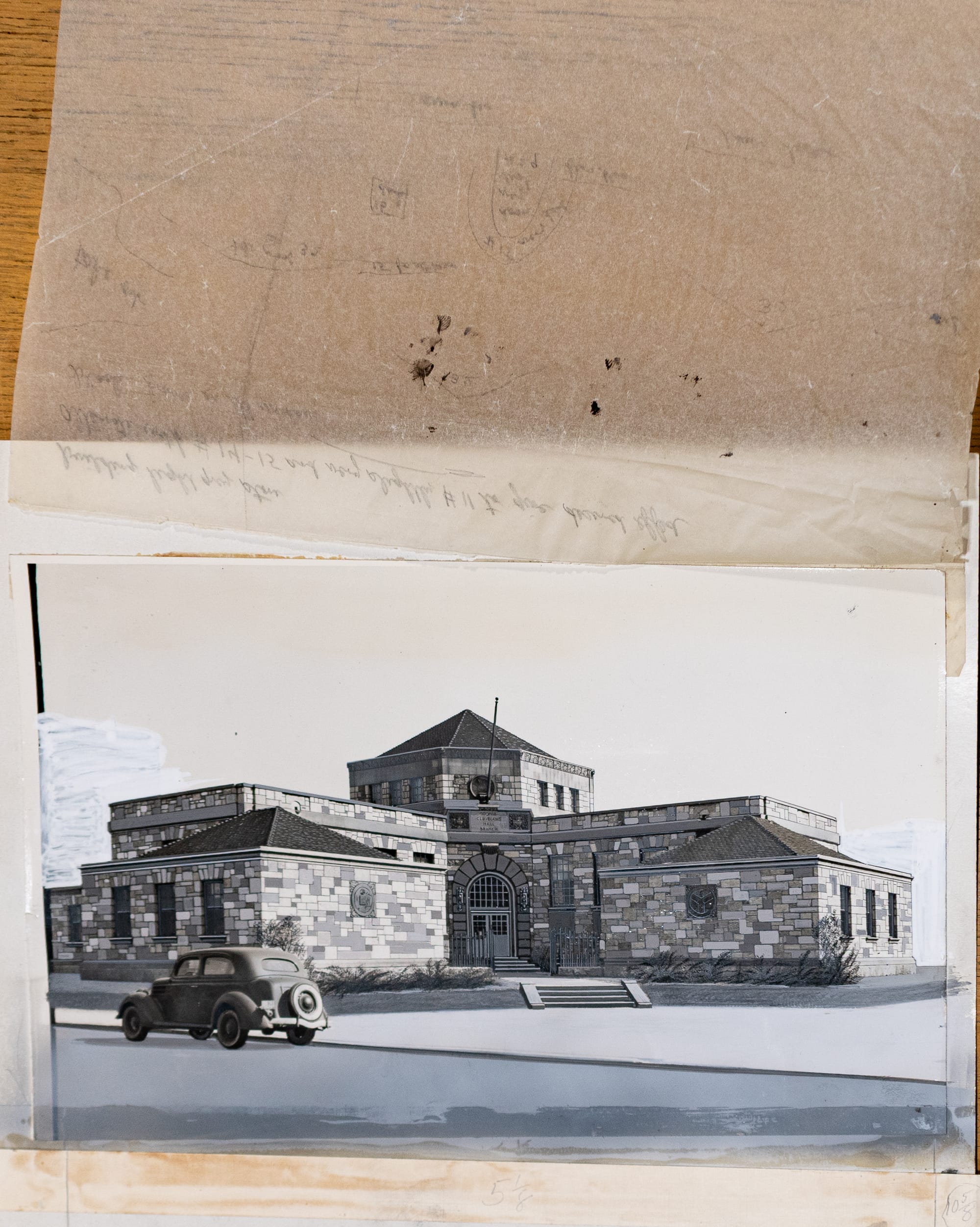

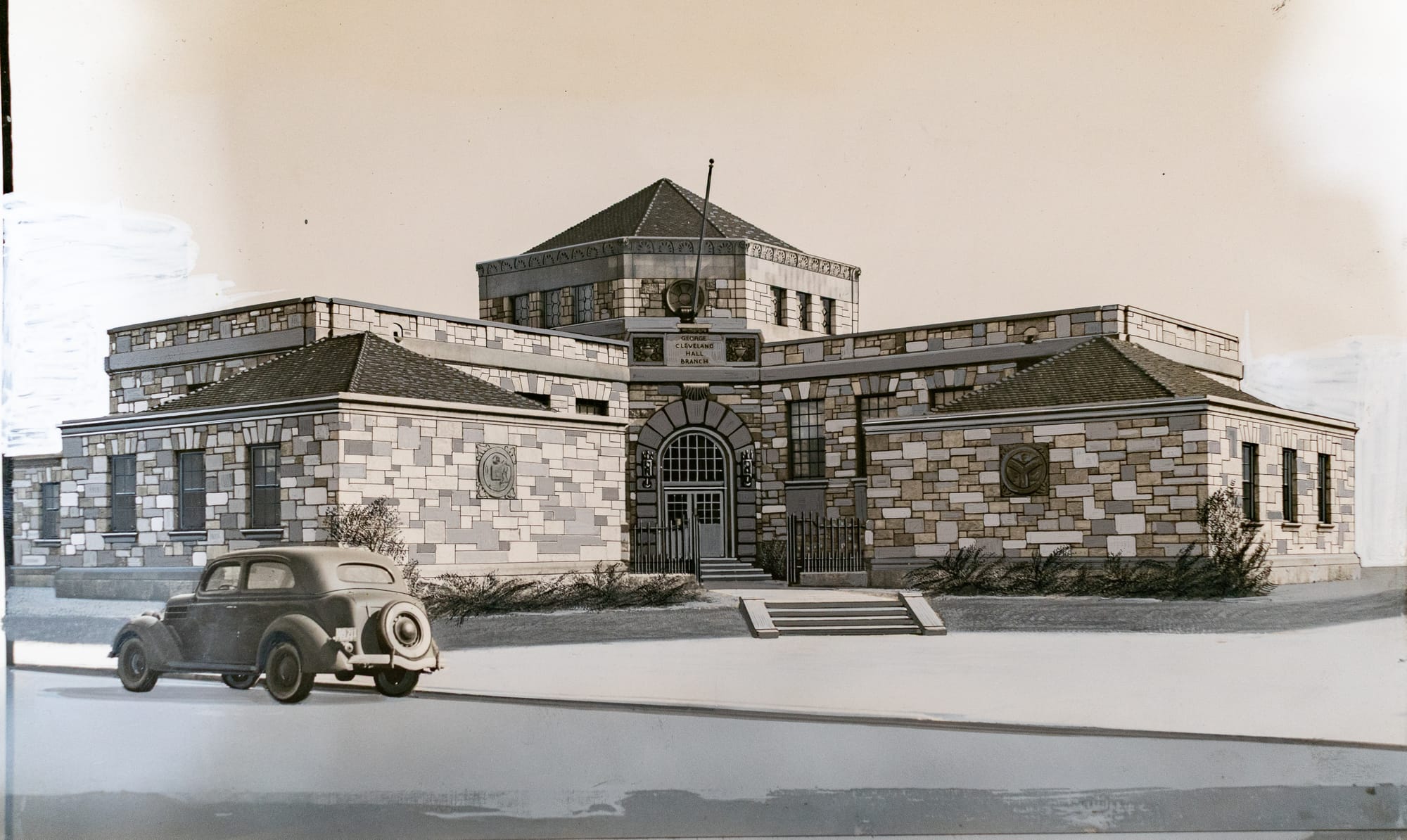

Rich set of production files in the Curt Teich Archive at the Newberry Library for this one. On the production order, we learn that it was commissioned by the Ben Franklin Store, a five-and-dime on 47th St. that was Chicago's first Black-owned department store–really shows what the Hall Branch Library meant to the community.

You can also see the retouching instructions on the tracing paper. The production order says, "do as little retouching as possible", so there are coloring instructions and then a few things instructed to "leave out", but ultimately it looks like a light-touch alteration.

Member discussion: