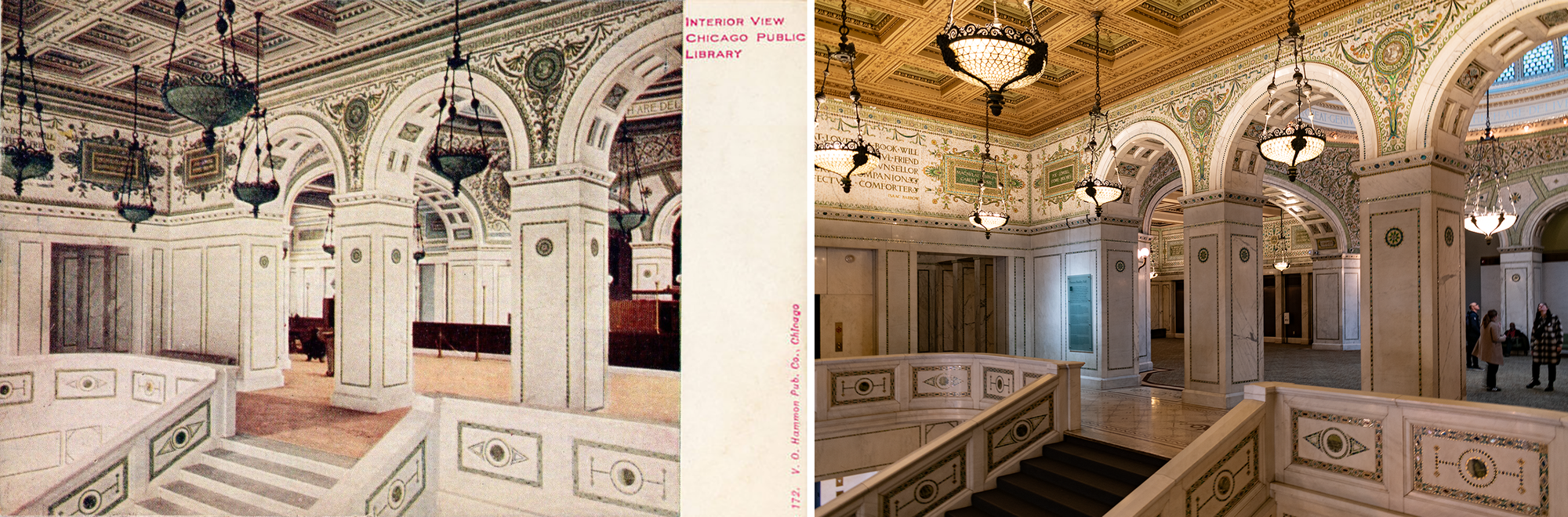

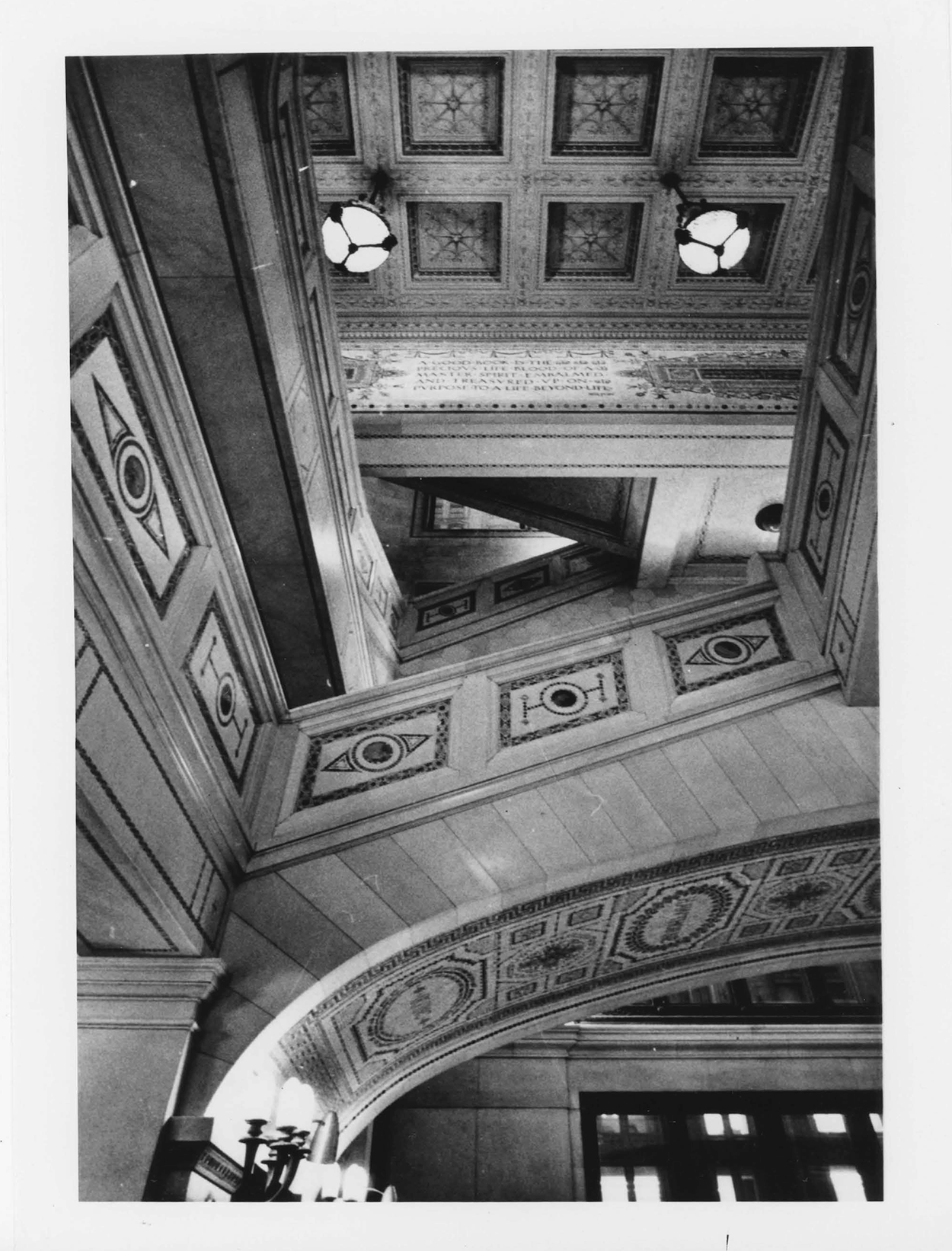

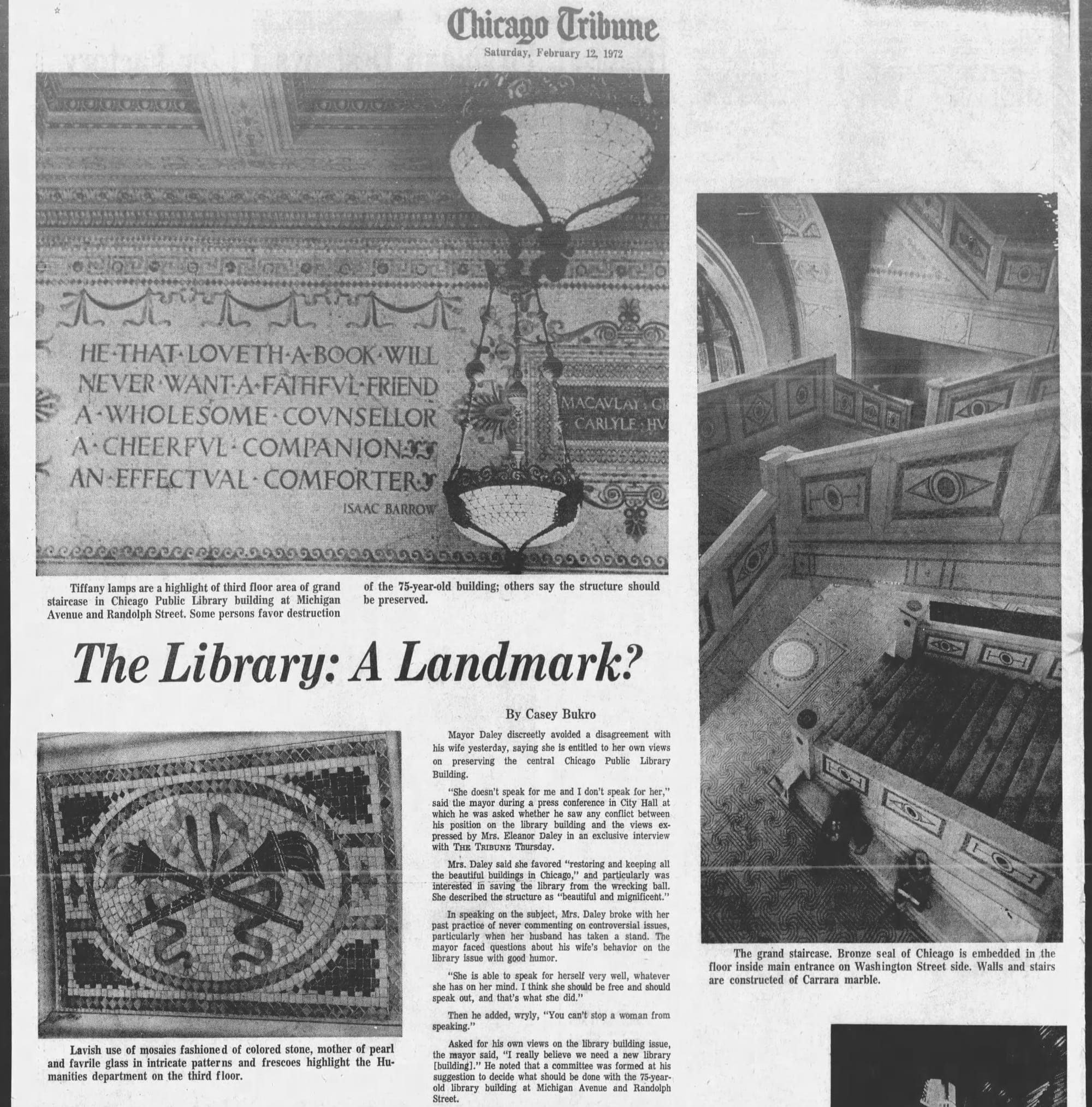

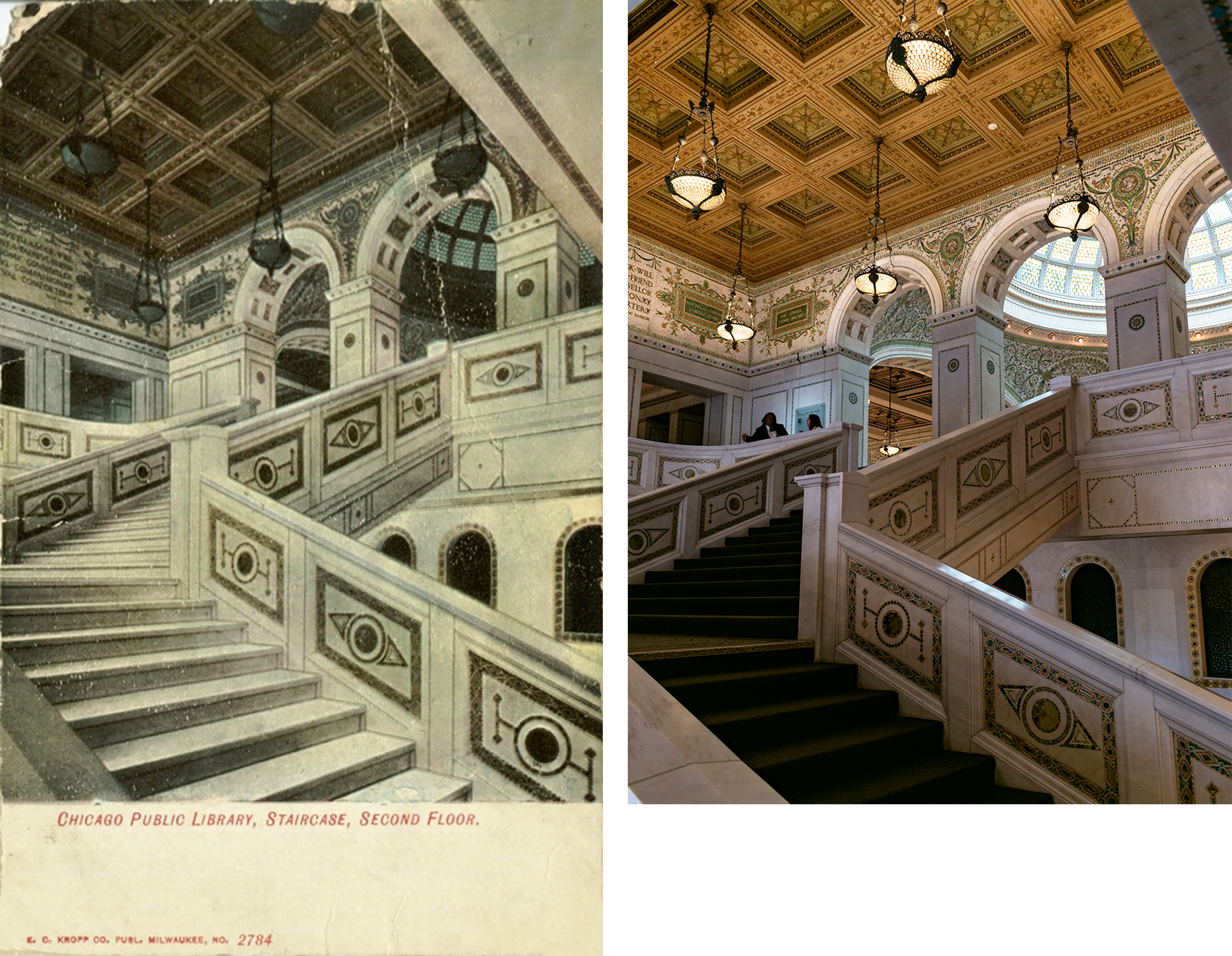

The crown jewel of a glorious mess, the grand stairway at the Chicago Cultural Center is an incredible celebration of the written word—which, of course, makes sense for a building that was Chicago’s first purpose-built public library when it opened in 1897.

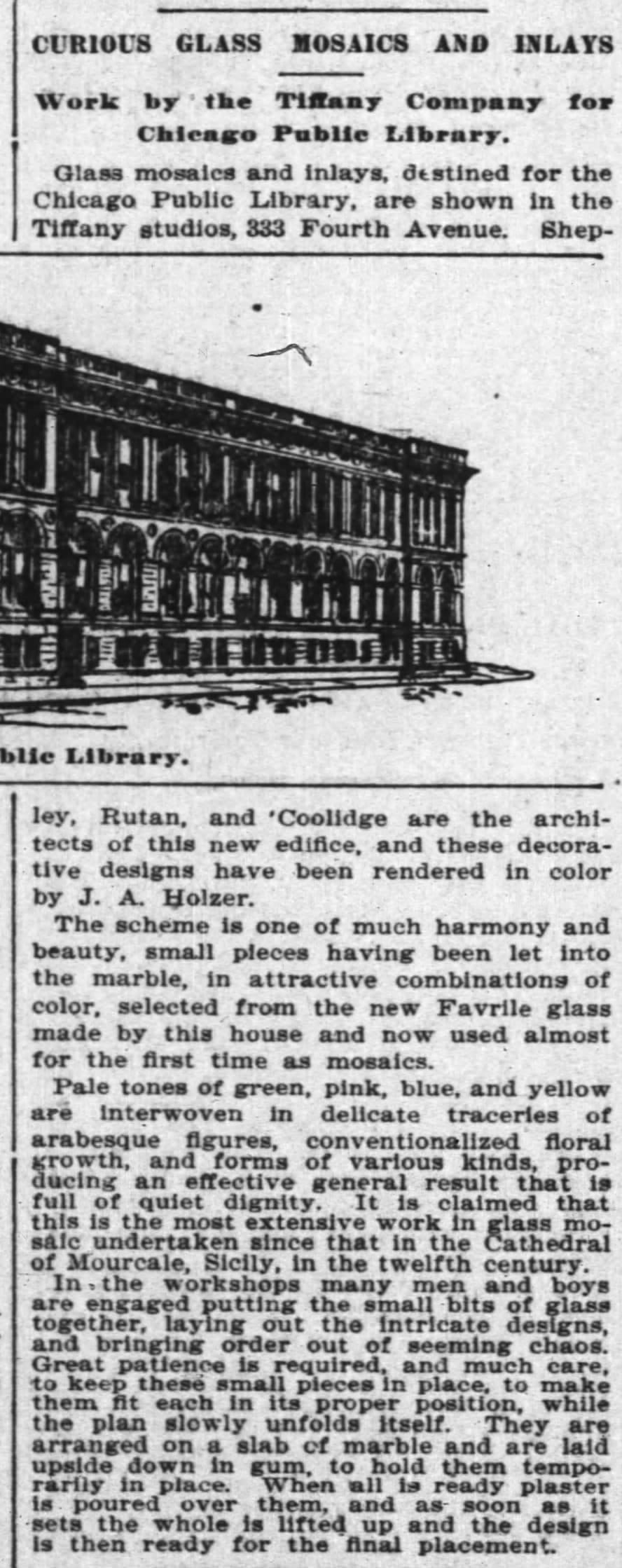

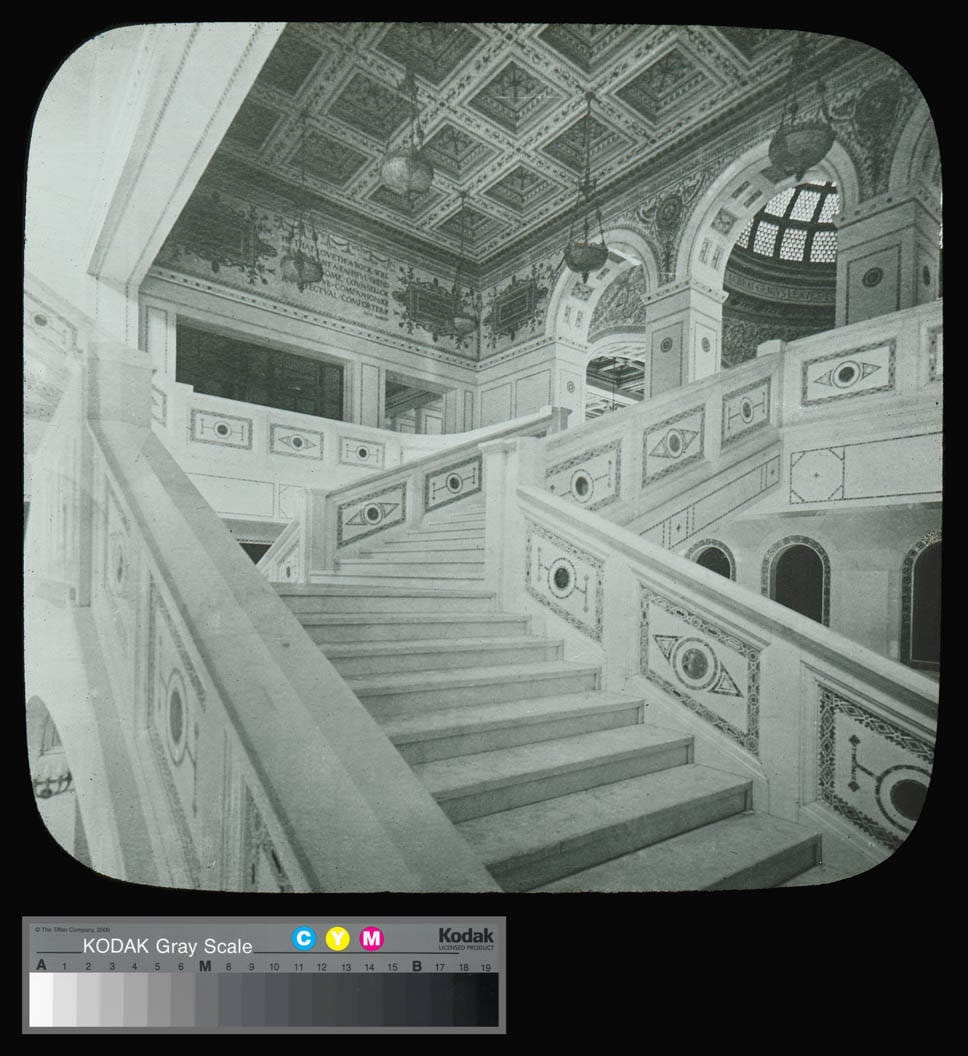

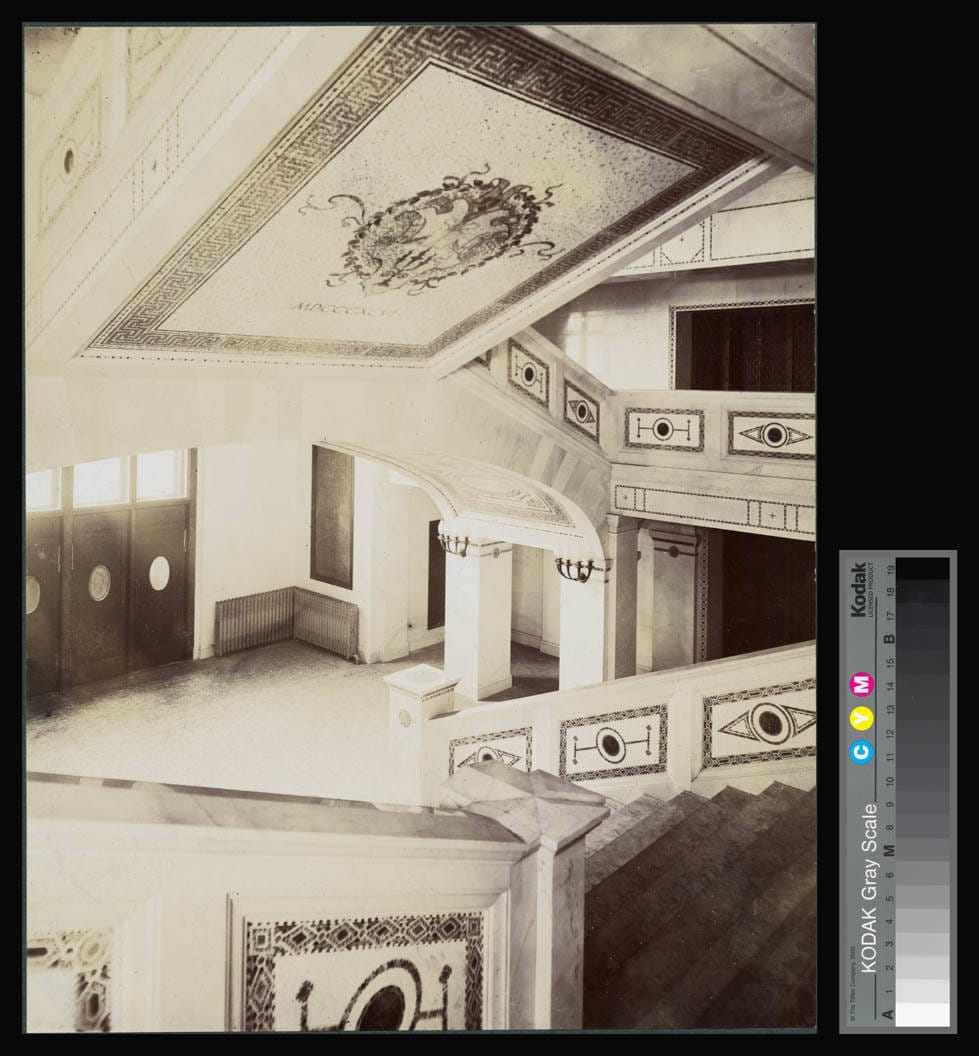

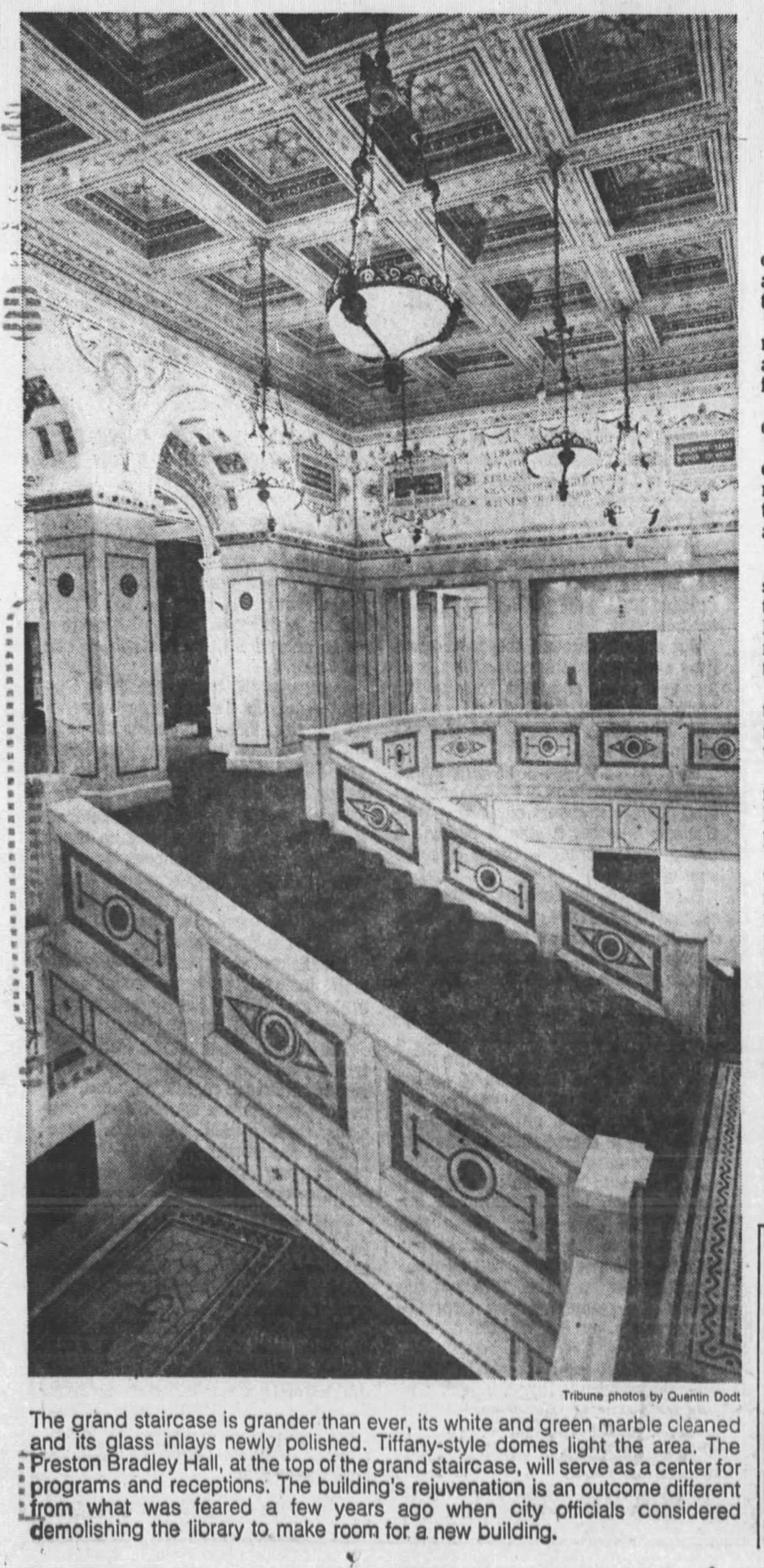

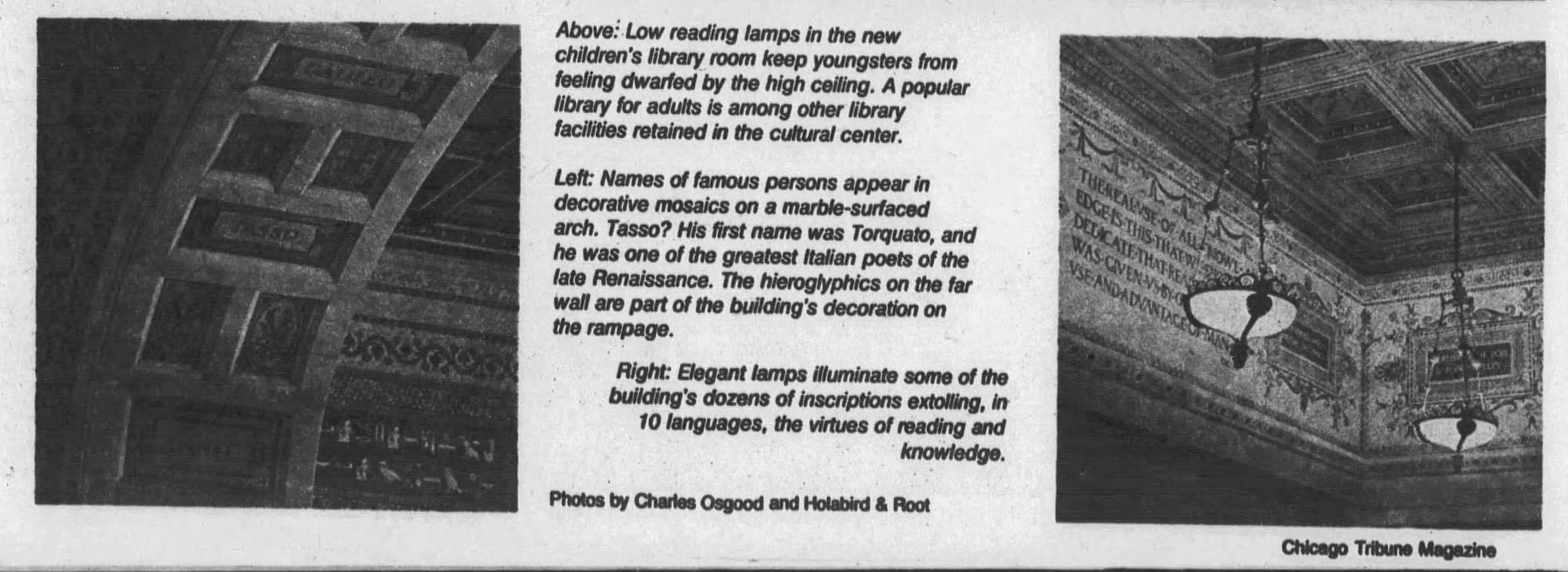

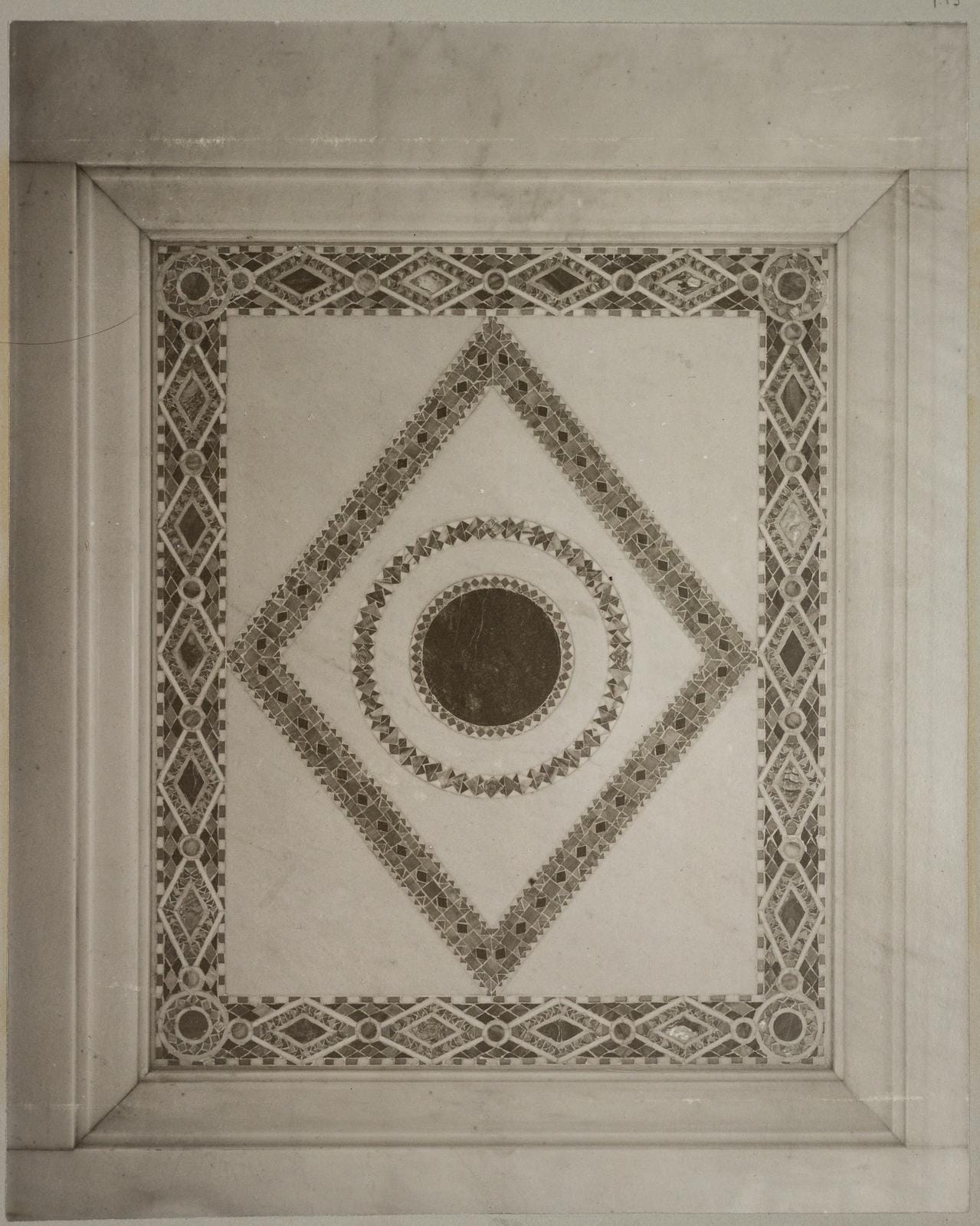

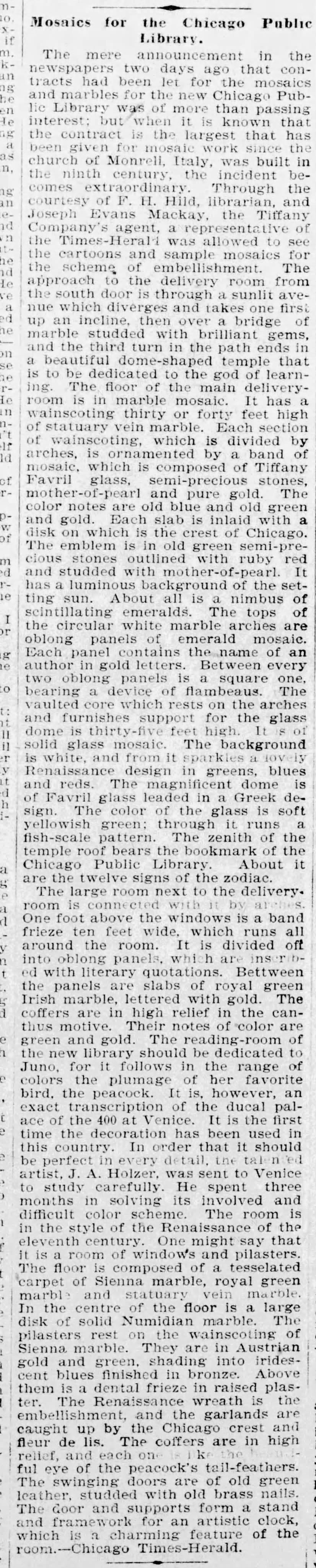

The glittering glass mosaics, claimed to be the most extravagant since the construction of the Cathedral of Monreale in Italy in the 12th century, were chosen as much for their practicality as their beauty—they’re easy to clean in a sooty, polluted city. Tiffany Favrile glass, mother of pearl, and green Connemara marble inlaid into the staircase’s white Carrara marble, design of the cosmati work is attributed to architect Robert C. Spencer and artist J.A. Holzer.

So, what’s changed? Despite a serious demolition scare in the 1960s and a complete change in purpose, basically nothing. The city added carpeting on the stairs and hung a small interpretive panel about Preston Bradley Hall, but otherwise the staircase and the mosaic work are in terrific shape after 125 years, despite little more than a light restoration in the 1970s, part of the building’s conversion to the Cultural Center.

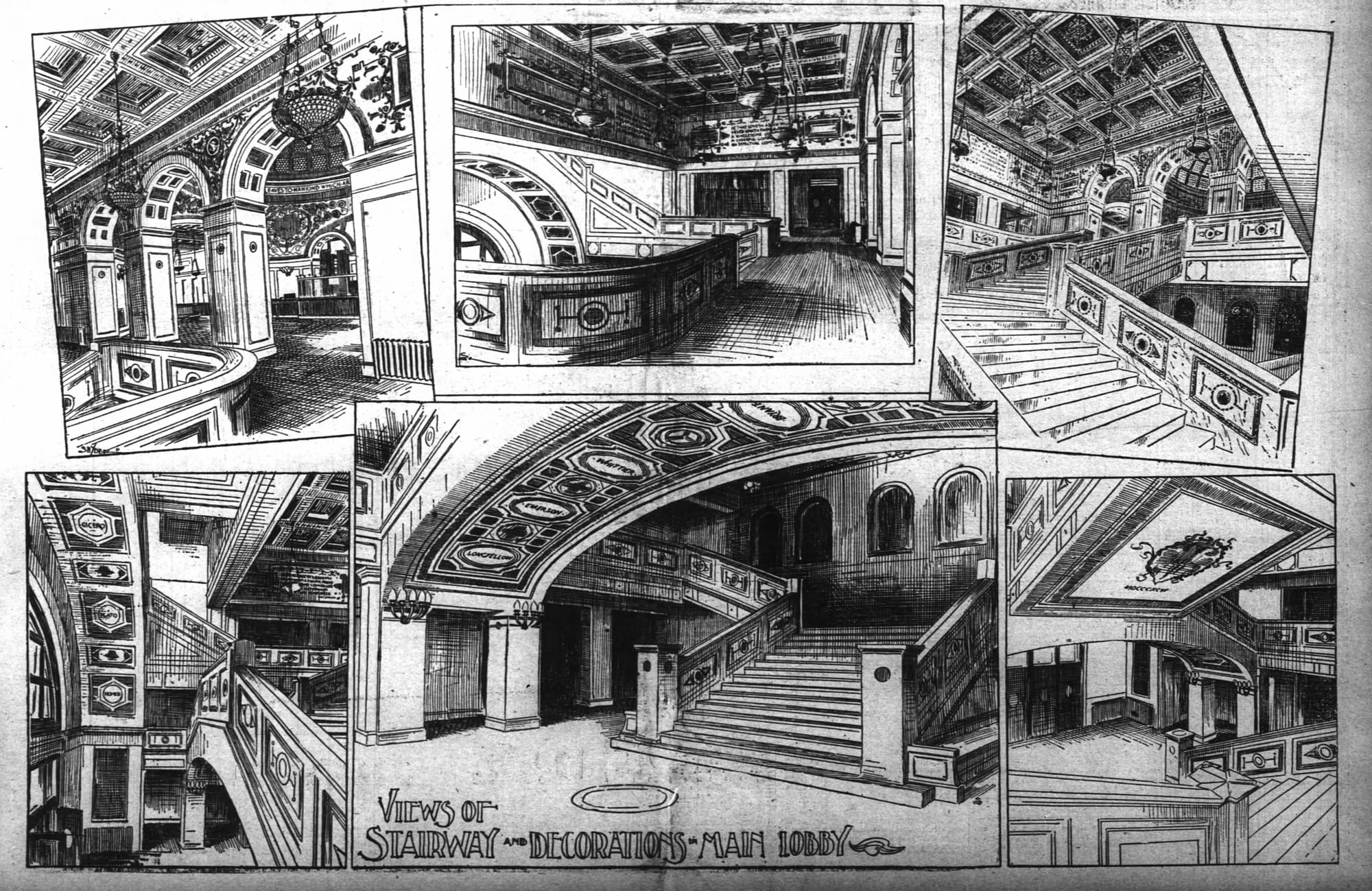

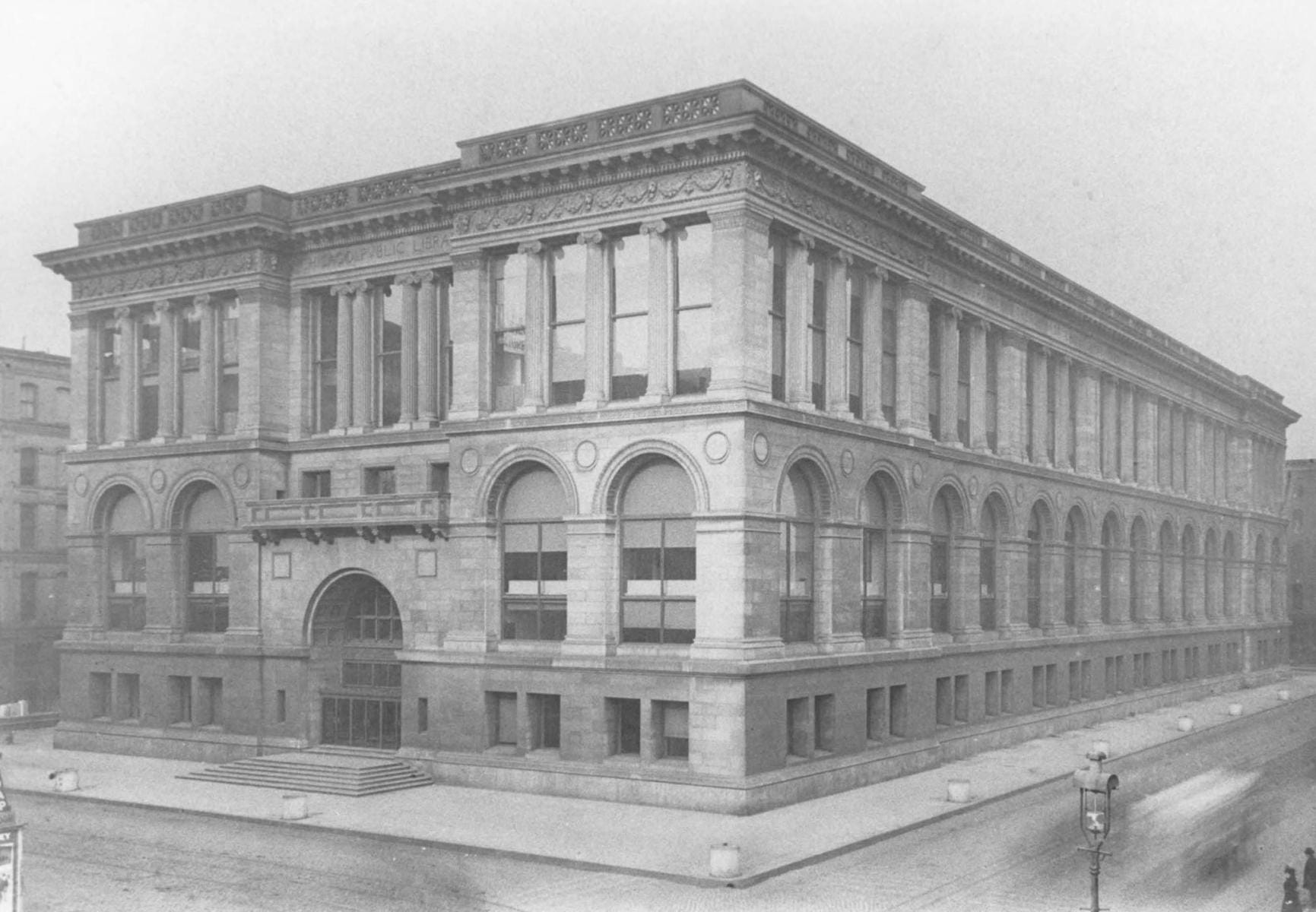

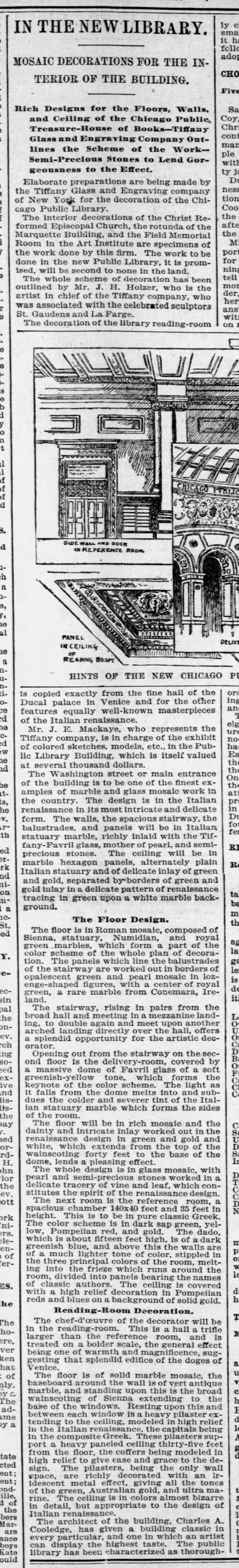

Constructing Chicago’s first permanent public library on this site was a decades-long ordeal, sealed with a clunky compromise that required the library share the building with the Grand Army of the Republic for its first 50 years. The result, designed by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, is kind of a mess—Greek neoclassical on its north elevation, Roman neoclassical on the south, and a full block of deadening repetition facing Michigan Avenue. The north entrance on Randolph, solemn and constrained, was envisioned as the entrance for the G.A.R. portion of the building. The south side, with this grand stairway, was the main library entrance—the incredible opulence of this stairway was the library celebrating and marketing themselves, differentiated from their awkward tenant on the other side of the building.

1895, Spencer leaves the architecture firm, the Inland Architect | 1896, the mosaics are on display in New York, New York Times | 1897, Louis C. Tiffany sends a request for a correction attributing the work to Holzer to the editor of House Beautiful | 1897, Reginald Capes, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections | 1897, Reginald Capes, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections | 1897, Reginald Capes, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections | 1897, Reginald Capes, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections | 1897, Reginald Capes, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections | 1897, Reginald Capes, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections

C.A. Coolidge led Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge’s work on the library, with architect Robert C. Spencer in charge of the interiors (presumably including the mosaics). Spencer left the firm and the project in 1895, well before the glass mosaics were installed, but by that point their design was far enough along that sketches, mockups, and models were being exhibited ahead of their installation in the under-construction building.

The Evans Marble Company did the marble floors, but subcontracted out the execution of the glass mosaics to the Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company. Collaborating with Spencer and the Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge team, Swiss artist Jacob Adolph Holzer spearheaded Tiffany’s work on the mosaics, particularly the color scheme. The Chicago Public Library commission came shortly after Holzer designed the lobby mosaics for the Marquette Building a few blocks away. Like Spencer, this would be some of Holzer’s last work with the firm that put him on the Chicago Public Library project, and some of his last mosaic work—after almost a decade working for Louis Tiffany, that working relationship ended in 1897.

1900, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections | 1900, lantern slide, Ryerson & Burnham Archives, Art Institute of Chicago | 1900, J.W. Taylor, Ryerson & Burnham Archives, Art Institute of Chicago | 1900, J.W. Taylor, Ryerson & Burnham Archives, Art Institute of Chicago | 1972, NRHP Nomination Form | 1972 article about landmark drive | 1977, stairway cleaned | 1977 restoration | 1979, restoration wins an award

The stairway arches are decorated with the names of the titans of literature (or at least those men considered as such in the 1890s—you don’t hear about Livy or John Greenleaf Whittier much these days [and it’s only men]), and their quotations adorn the friezes on the landing. With green Connemara marble from Ireland inlaid into white Carrara statuary marble from Italy, the stairway mosaics are a gaelic-garlic combo that feels like an unintentional nod to two of the ethnicities who would come to define Chicago.

Still one of the wildest interiors in the city of Chicago—and maybe the United States—the former main branch of the Chicago Public Library was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and, more importantly, designated a Chicago landmark in 1976 ahead of its conversion into the Chicago Cultural Center.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Tiffany’s Glass Mosaics by Kelly A. Conway, specifically “The Life and Work of Jacob Adolphus Holzer" by Elizabeth J. De Rosa

- NRHP Nomination Form

- "Chicago's New Public Library" in the Outlook, 1897

- Special supplement in the Inland Architect in 1897

- The restoration and conversion in Progressive Architecture in 1977

- "Tiffany on High" in Traditional Building, 2008

The grand stairway stood in for the entrance to the opera in The Untouchables in 1897.

When it was built, the Monreale Cathedral in Italy was the most frequent comparison for the library's bonkers mosaics.

2015, José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro, Wikimedia Commons | 2022, Holger Uwe Schmitt, Wikimedia Commons | 2022, Holger Uwe Schmitt, Wikimedia Commons | 2022, Holger Uwe Schmitt, Wikimedia Commons | 2022, Holger Uwe Schmitt, Wikimedia Commons

but the closest comparison is really the Marquette Building lobby, also executed by Holzer in Chicago in the 1890s.

HABS ILL,16-CHIG,70-10, Wikimedia Commons | 2011, John Picken, Wikimedia Commons | 2013, Jaysin Trevino, Wikimedia Commons

After leaving Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, Robert C. Spencer started his own firm. Working in the Prairie Style, he was (at least for a while) Frank Lloyd Wright's best friend and shared an office with him. Spencer designed the Denkmann-Hauberg Mansion in Rock Island, as well as a bunch of homes in River Forest, Oak Park, Riverside, Hinsdale, and Evanston.

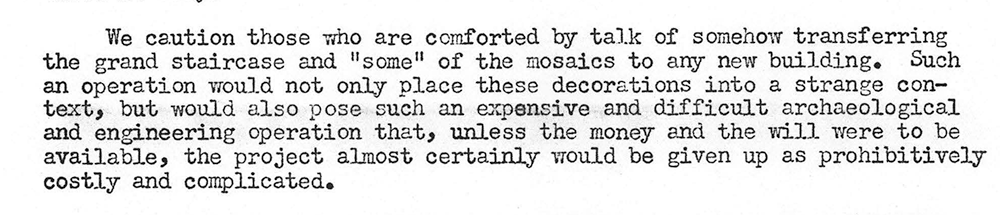

Hard to believe that this—transferring the staircase and its mosaics—was even considered when they were weighing demolition in the late 1960s.

1969 letter to NRHP Keeper of the Records William Murtaugh from the Chicago Heritage Committee, NRHP Nomination Form

1897, Reginald Capes, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections | 1897, Reginald Capes, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections | 1897, Reginald Capes, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections | 1900, J.W. Taylor, Ryerson & Burnham Archives, Art Institute of Chicago | Two 1895 articles about the in-progress mosaics

The spots where I took these three photos from.

Member discussion: