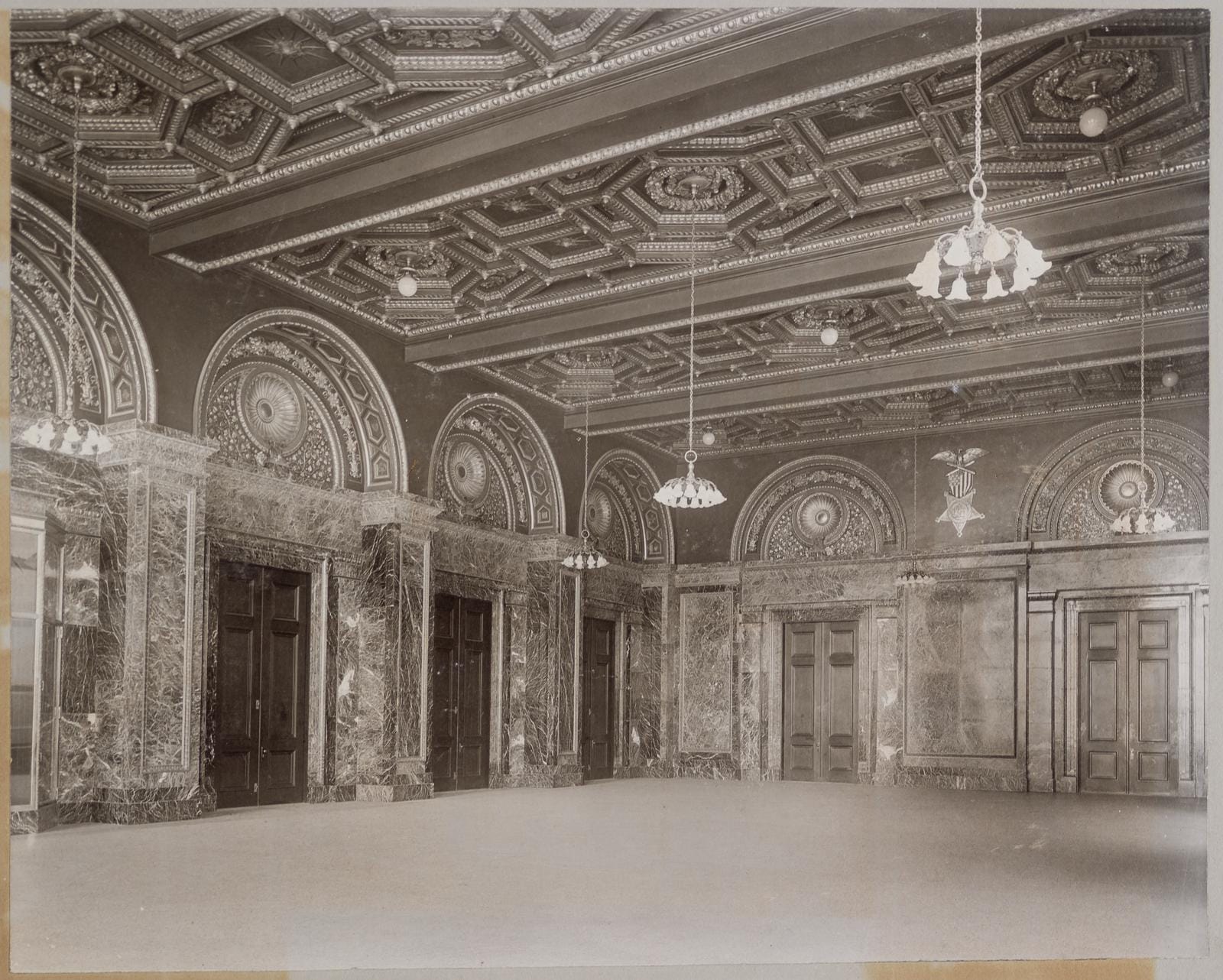

Verd antique, coffered ceilings, and engraved with the names of Civil War battles, the Grand Army of the Republic Memorial Hall in the Chicago Cultural Center is the grandiose relic of a contentious compromise.

Designed by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge and completed in 1897, the G.A.R. Memorial Hall was the awkward kludge that threaded the needle between the state government’s commitments to the Grand Army of the Republic—a fraternal organization for Union veterans—and the city of Chicago’s need for a main public library. With the northern quarter of this site deeded by the state to the Soldiers’ Home for a memorial hall, but the Chicago Library Board maneuvering to repeal that law and replace it with one that secured the entire site for itself, the Grand Army of the Republic, the Chicago Public Library, and the State of Illinois struck an agreement—the library would take over entire site on the condition that they build a memorial hall, maintained in perpetuity, and provide the G.A.R. office and assembly space for a nominal fee on a 50 year lease.

It was an uneasy cohabitation, bristling into conflict any time the status quo wobbled: during construction in the 1890s, as the G.A.R. lease expired in the 1940s, when the city contemplated demolishing the library in the 1960s, and as the building transformed into the cultural center in the 1970s. With its collection of Civil War artifacts and documents now in the Chicago Public Library Special Collections Division at the Harold Washington Library, an immaculate G.A.R. Memorial Hall reopened in 2022 after a $15m restoration, led by Harboe Architects and funded by an anonymous donor.

So, what’s changed? The vitrines, benches, and busts are gone—the G.A.R. Memorial Hall is no longer a little museum—but it sounds to me like it was a dusty, static display anyway. Many of the items—on view, unmoved, and exposed to sunlight for decades—apparently needed serious conservation work once they entered the CPL collection. While its programming has changed quite a bit, the space itself is positively gleaming after the restoration, which removed an unfortunate layer of drab gray paint applied to the G.A.R. hall in the 1970s, refurbished doors and display cases, and remade the long-lost original chandeliers. Harboe Architects and their partners all killed it here, well done.

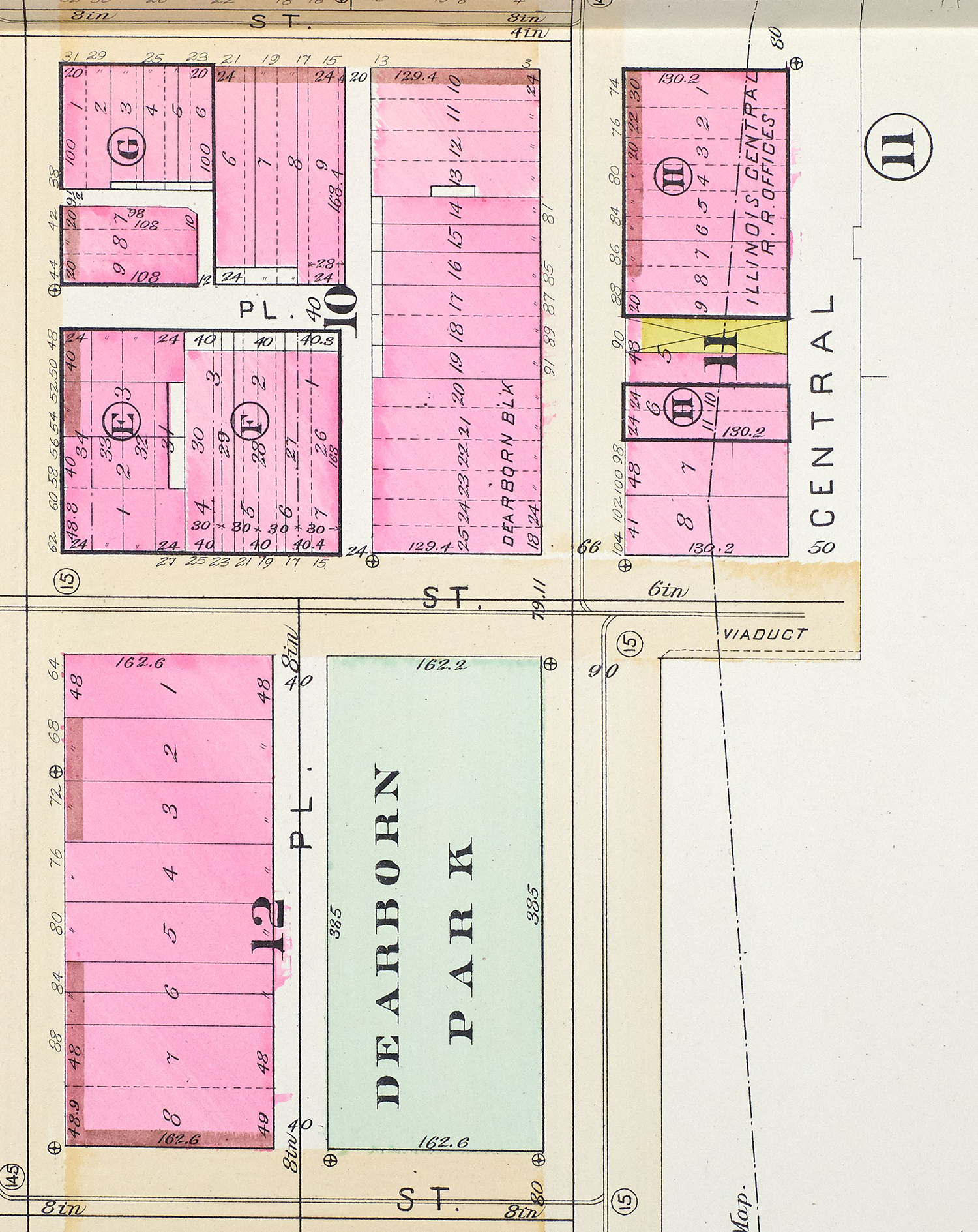

Before it was shared by the Grand Army of the Republic and the Chicago Public Library, this site once formed part of the grounds of Fort Dearborn—for decades it remained the property of the U.S. Department of War. Known as Dearborn Park, it persisted as a windswept and treeless square long after its eponymous fort had been swallowed up by a growing Chicago. Disentangling the site from the federal government took years, an effort led by Illinois senator (and Civil War general) John Logan (ever wondered where Logan Square got its name?). Senator Logan shepherded multiple bills through Congress that would hand the site over to a tripartite consortium: the G.A.R., the Chicago Public Library, and a design academy. They all failed (Congress did not want to hand over federal land to a design school), but the point was moot in the end—in a circuit court decision, Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan ruled that the land belonged to the state of Illinois after all.

Dearborn Park, 1890, Chicago Public Library Special Collections via Chicago Collections | 1886 fire insurance map showing Dearborn Park | 1893 fire insurance map showing the future site of the Chicago Public Library

The library board and the G.A.R. went to work lobbying the state, but no longer in cooperation with each other—the library realized that they needed the entire site (and presumably thought they had enough clout to handle the Illinois General Assembly on their own, without the G.A.R.’s pull). However, the Grand Army of the Republic was an incredibly influential organization in its own right, with more than 30,000 members in Illinois (the state where it was founded). In 1889, the G.A.R. stole a march on the library board when the Illinois General Assembly deeded the northernmost quarter of the site to the Soldiers’ Home of Chicago to build a memorial hall on behalf of the Grand Army of the Republic.

The Chicago Library Board began maneuvering to repeal that law and replace it with one giving control of the entire site to the library. As that effort gained momentum, the G.A.R. traded their early, fragile advantage for something longer term that avoided an arduous political fight. The G.A.R. only needed a small portion of the site anyway, so they traded the deed to the northernmost portion of the site to the library board in exchange for a permanent memorial hall in the new library as well as a 50-year lease on office, meeting, and assembly space for a nominal fee.

1897, the story of the site | 1897 articles about the G.A.R. being angry with the library | 1898 articles about the G.A.R. veterans moving in and the new memorial hall

Even after the compromise was agreed and construction began, the G.A.R. and the library board bickered over specifics basically up until the day the G.A.R. took formal possession of the space in 1898. That 50 year lease, for example, became a 30 year lease (which decades later would be extended another 20 years).

Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge—the firm who designed the Art Institute—won the (pretty messy) design competition for the new main library. With design work led by architect C.A. Coolidge, the firm tried to balance the building’s dual (and dueling?) tenants by providing them dedicated entryways—they intended the relatively modest Randolph Street entrance to serve the G.A.R., while library patrons would enter through the opulent Washington Street entry.

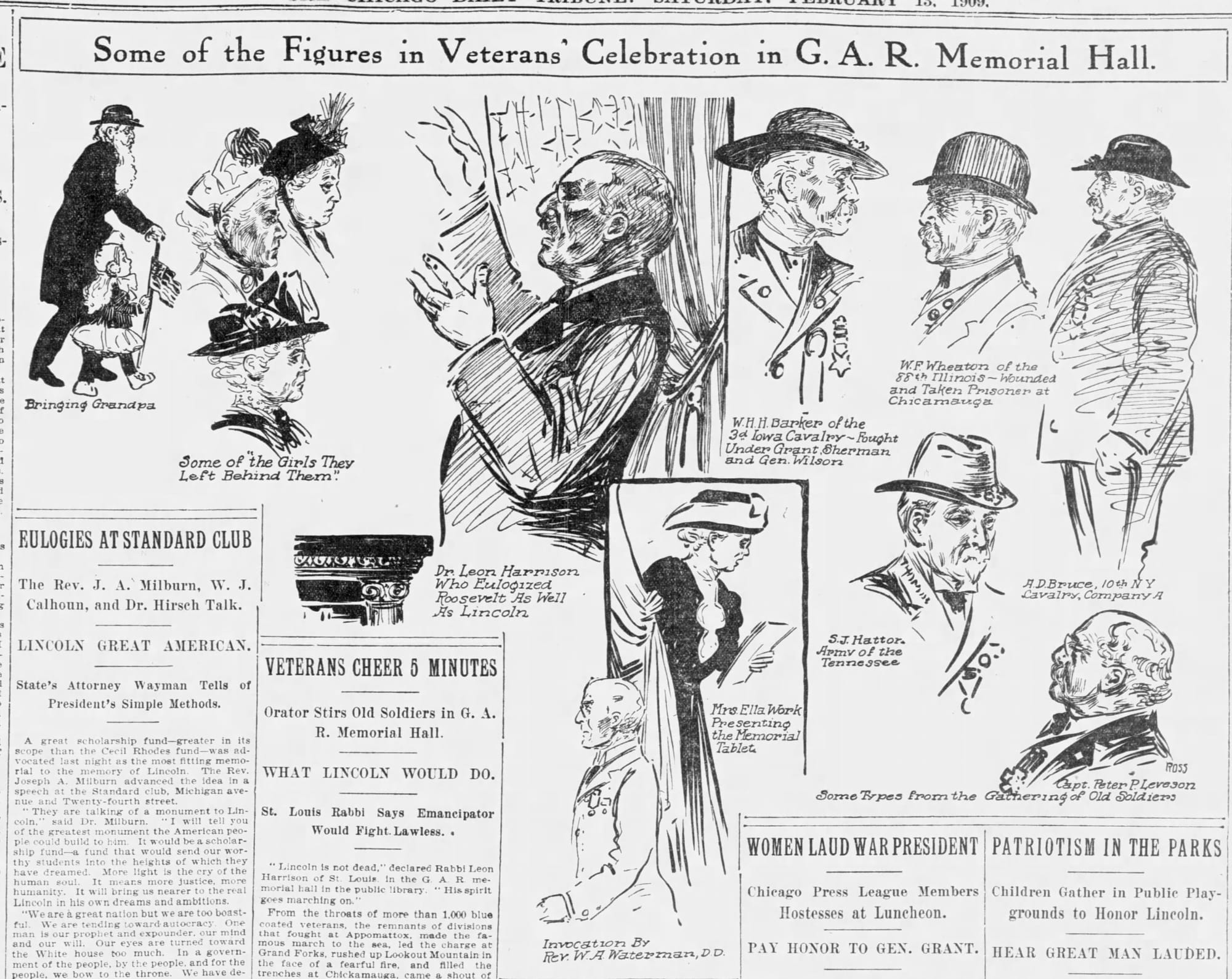

1897, Reginald Capes, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections | 1897, Reginald Capes, Chicago Public Library Archives via Chicago Collections | 1899, President McKinley at the G.A.R. Memorial Hall to meet old soldiers | 1909 veteran celebration

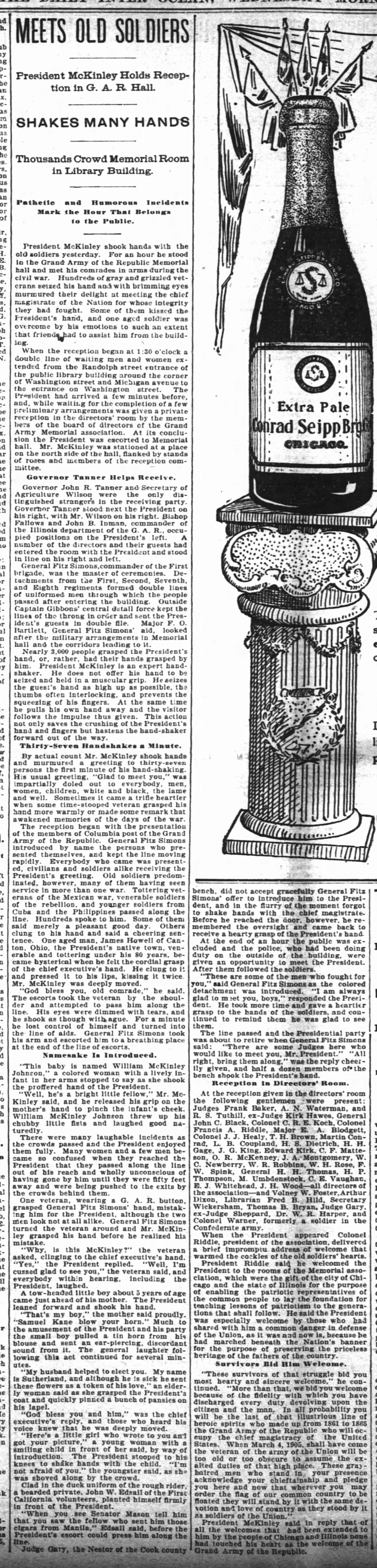

The G.A.R. received a suit of rooms on the north side of the building, including office space, a meeting room, the grand rotunda, and this room, a monument and a museum to Union Army veterans and their victories in the Civil War. Clad with dark green verd antique stone with an extravagant coffered ceiling, vitrines and display cases in the memorial hall held books, documents, and photos, as well as memorabilia like Ulysses S. Grant’s saddle, Gen. Sherman’s uniform, George Custer’s hat, etc. The G.A.R. also used it for major events—President McKinley posted up and shook three thousand hands here in 1899, and it was a key venue for the massive G.A.R. national encampment Chicago hosted in 1900.

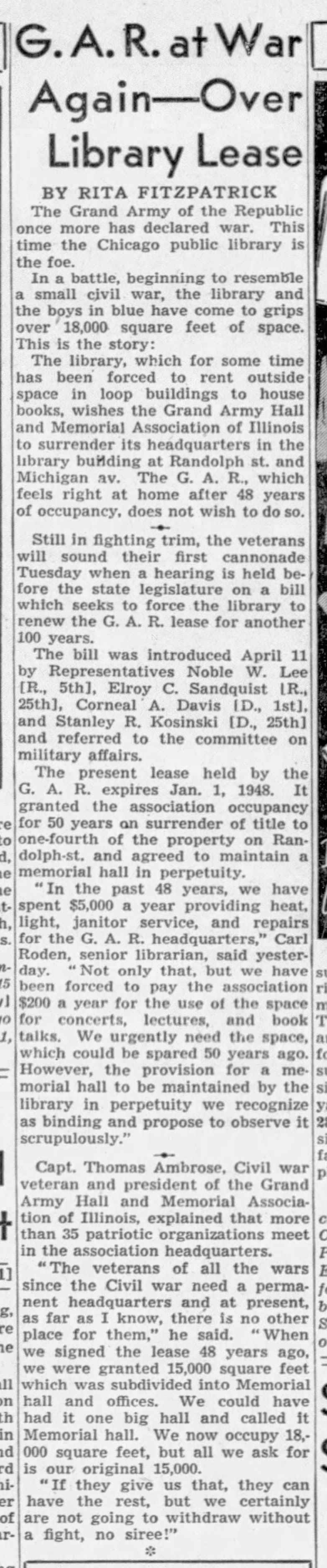

After yet another skirmish in the Illinois General Assembly between the G.A.R. and the Chicago Public Library, the library took over the G.A.R. rooms and their collections in 1948—by that point, there were only a few G.A.R. members left in Illinois. The library left the memorial hall mostly unchanged at first, and the GAR Memorial Association and Sons of Union Veterans maintained a small office in the building.

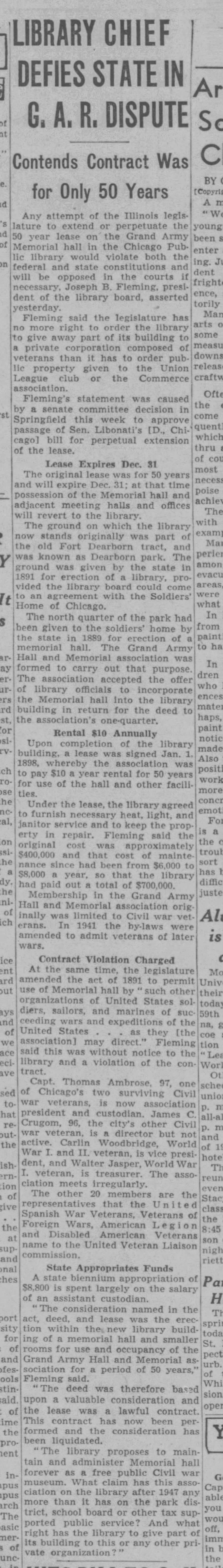

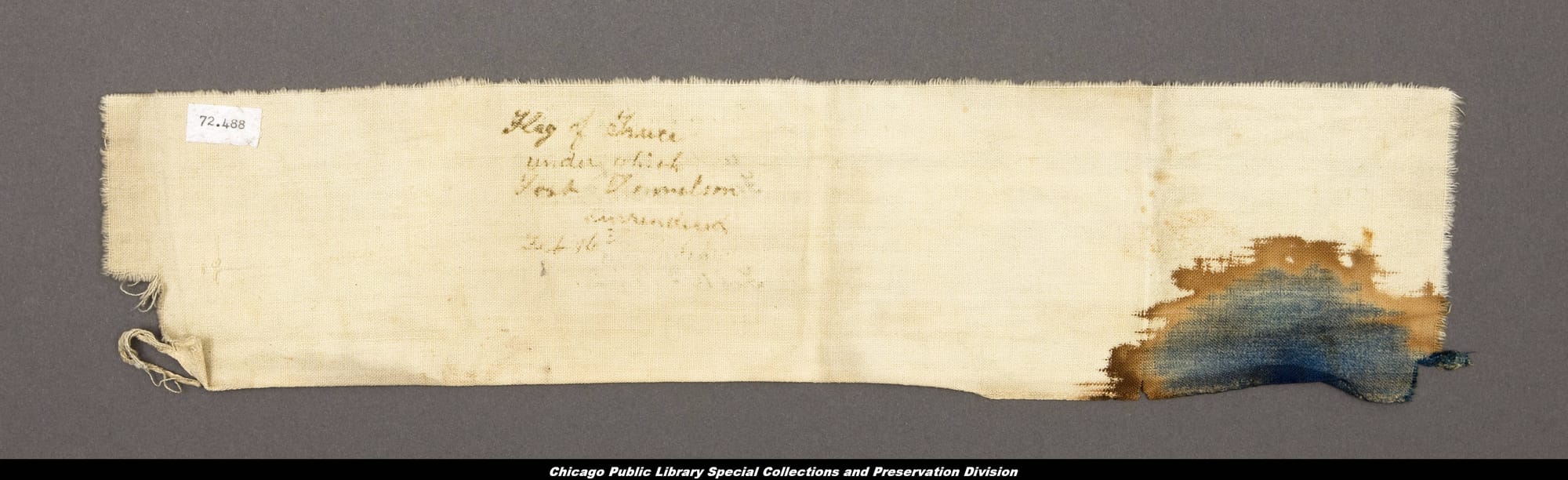

1945, G.A.R. at war over the lease | 1947 articles about the fight over a lease renewal | George Armstrong Custer's hat, in the G.A.R. Collection of the Chicago Public Library | Truce flag, in the G.A.R. Collection of the Chicago Public Library | Ulysses S. Grant stirrups, in the G.A.R. Collection of the Chicago Public Library | 1953, CPL works to restore the museum in the memorial hall | 1961, some interesting photos from inside the room when it was still a little museum

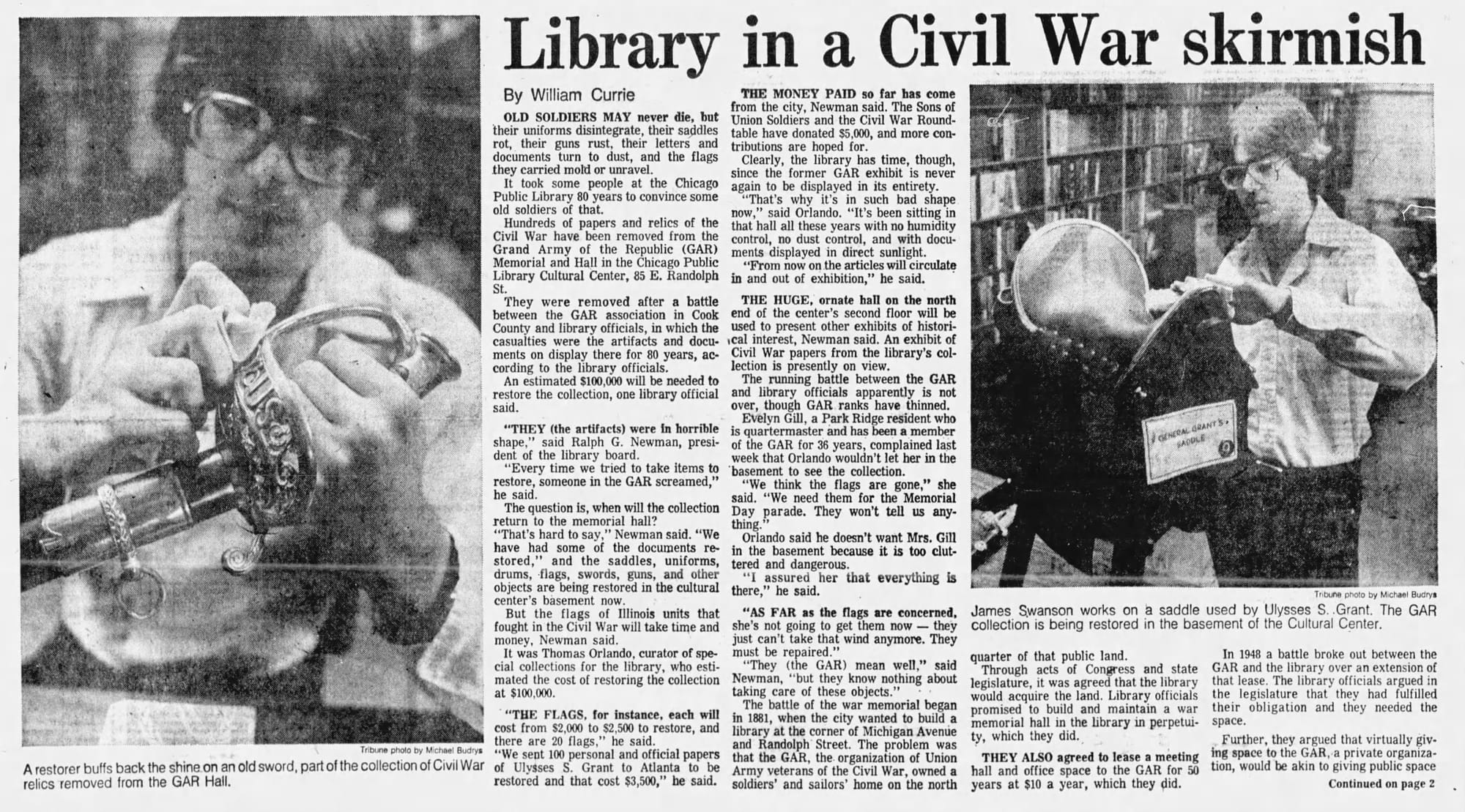

By the 1960s, though, the Chicago Public Library had outgrown the building, with demolition a serious possibility. The ensuing preservation battle and decision to repurpose the building as the Chicago Cultural Center once again kicked off a kerfuffle about the future of the G.A.R. Memorial Hall and its collection. Someone made a mystifying decision to douse the room in drab gray paint, but the bigger point of contention was the collection, which by the 1970s had been on display, in sunlight, continuously for decades and had seriously deteriorated. CPL received ad hoc donations to conserve items, but taking them off view for conservation purposes ruffled feathers. The G.A.R.’s few remaining champions feared that the library was trying to edge them out even further and shrink the responsibilities of the library’s promise to maintain the memorial hall into irrelevance.

(Which, you know, the library probably was! The G.A.R. stuff didn’t really align with their main mission and it’s clear they’d rather not have had them as a tenant in the first place—entirely understandable they’d want to edge them out after 80 years.)

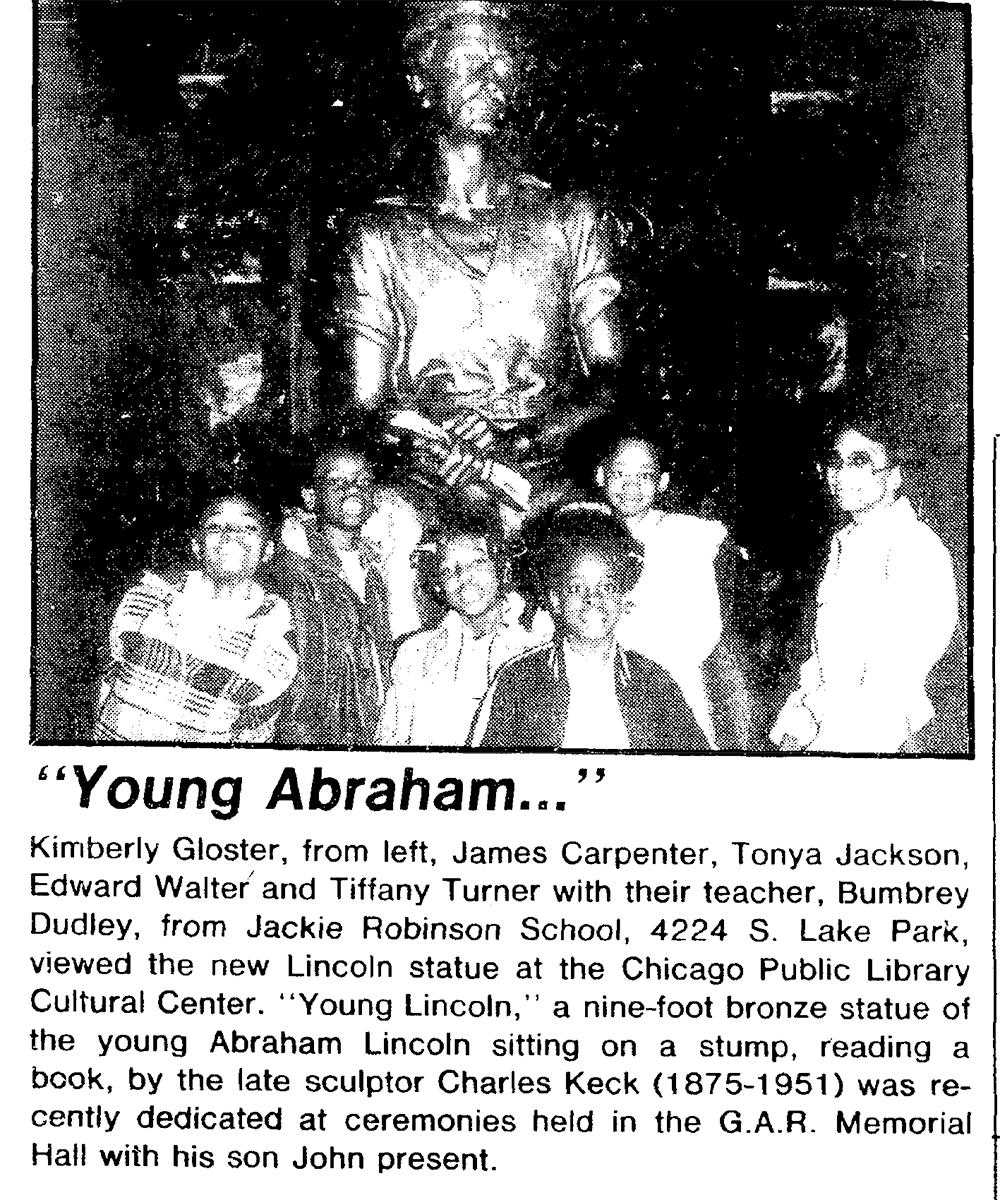

1978 article about the fight over the artifacts in the G.A.R. collection | 1980, kids with the newly-donated "Young Lincoln" statue, the Chicago Defender | Dr. Scholl library exhibition, 1982 | 1979, St. Peter's Basilica model | 1982, Black history exhibition

After the building was converted into the Chicago Cultural Center in 1977, you can see the types of programming hosted in the memorial hall expand—starting in the late 1970s and in the 1980s, the memorial hall hosted exhibitions on Black history, Carl Sandburg, miniature books, Dr. Scholl, Poetry Magazine, etc. Shortly after opening their new main library in 1991, the Chicago Public Library permanently moved the G.A.R. artifacts to their Special Collections Division at the Harold Washington Library Center (a bronze statue of Young Lincoln, donated to the city by the family of sculptor Charles Keck and installed in the memorial hall in 1980, was moved outdoors to Senn Park). The G.A.R. Memorial Hall spent much of the last 40 years as a venue for weddings, receptions, and exhibitions (including the Chicago Architecture Biennial’s Horizontal City in 2017).

Covered with gray paint and obscured by (now unfashionable) dark glass after the 1970s remodel, the G.A.R. Memorial Hall was the slightly dowdy sibling to the gorgeous Preston Bradley Hall and its Tiffany dome on the other side of the Cultural Center. A quirky jewel hidden under a layer of questionable decisions, the G.A.R. hall was crying out for a restoration—and in 2019 Chicago Cultural Historian Tim Samuelson helped snag a $15m donation from an anonymous foundation to make it happen.

Led by Harboe Architects, the restoration resurfaced the memorial hall’s original Tiffany paint scheme, replaced the dark windows, refinished all the metal and plaster ornamentation, refurbished the cherrywood display cases along the walls, and remade the room’s lost chandeliers. Reopened in 2022, the restored G.A.R. Memorial Hall is once again a shining monument to the Union veterans who ended chattel slavery in the United States and a welcoming, inviting space for Chicagoans within their People's Palace.

2025, me

Production Files

Further reading:

- NRHP Nomination Form

- Special supplemental section in The Inland Architect devoted to the new main branch of the Chicago Public Library in 1898

- "Remembering the Grand Army of the Republic" in Chicago History, 2015

- Some very neat restoration photos here from a conservation technician

- ...but really just watch the video below on the restoration, it's great

1886 fire insurance map | 1893 fire insurance map | 1901 fire insurance map | 1906 fire insurance map | 1950 fire insurance map

Thirtysome years after he originally sculpted it, Charles Keck's family donated a cast of Young Lincoln to the City of Chicago and it was initially placed in the G.A.R. Memorial Hall. While thematically appropriate, it seems like a weird place for a monumental bronze piece—in 1997, the Chicago Public Library loaned it to the Chicago Park District and it was installed in Senn Park.

1981, Chicago Tribune | 2010, Alan Scott Walker, Wikimedia Commons

Where I took the present-day photo from.

Member discussion: