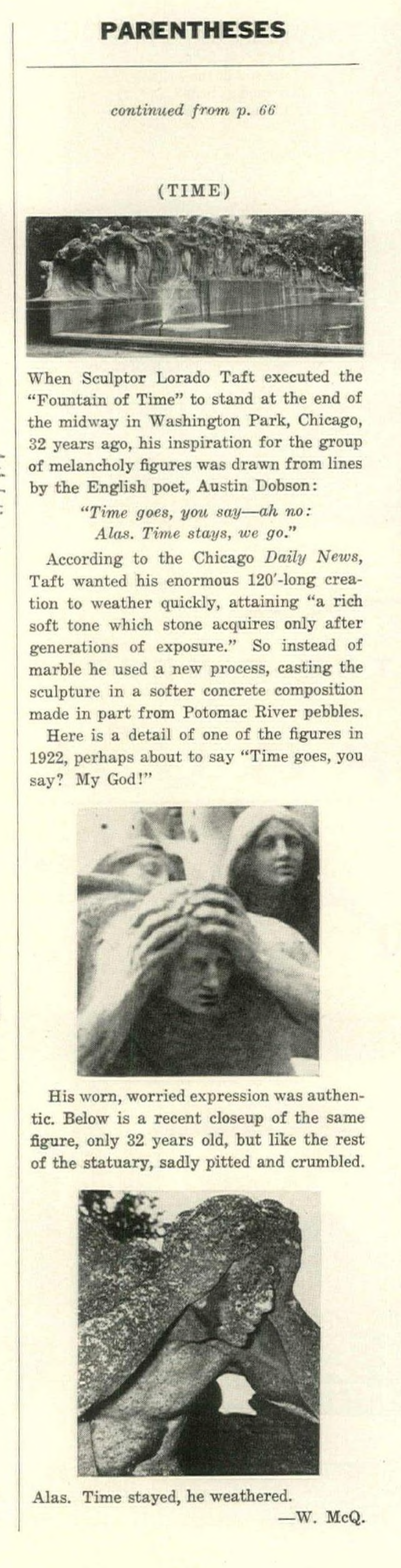

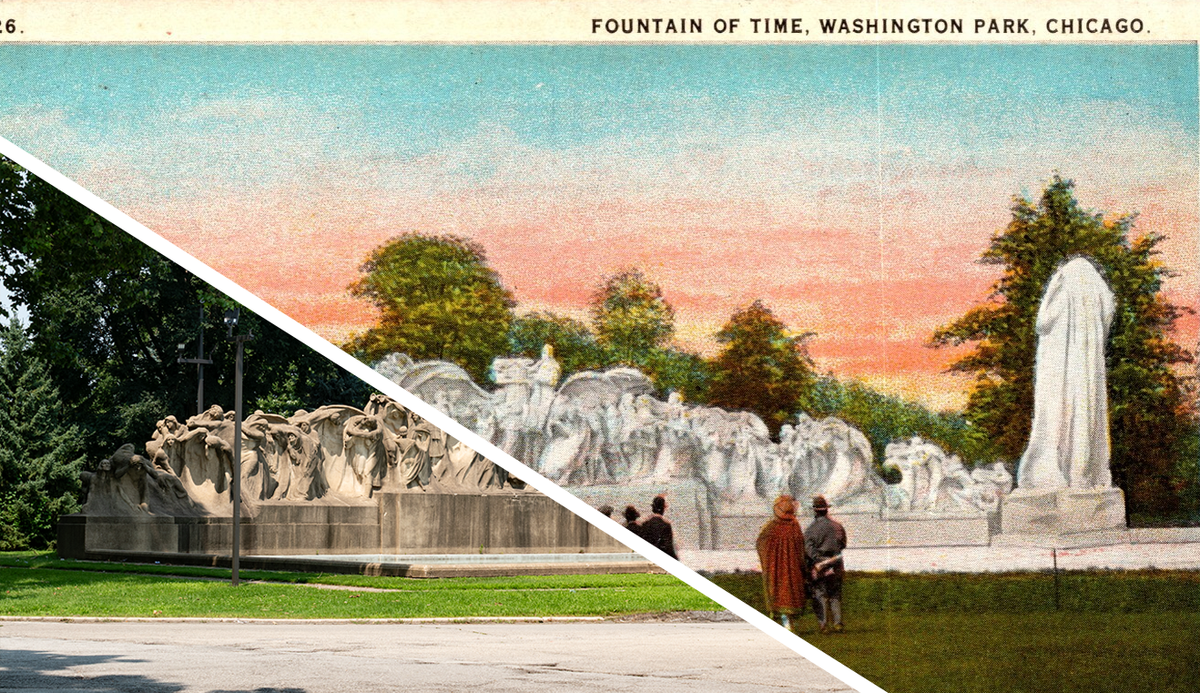

Fitting for a monumental artwork inspired by the bittersweet Henry Austin Dobson couplet “Time goes, you say? Ah no! Time stays, we go;”, Lorado Taft’s Fountain of Time is both one of the most extraordinary pieces of public sculpture in Chicago and a testament to thwarted ambition and groundbreaking decay.

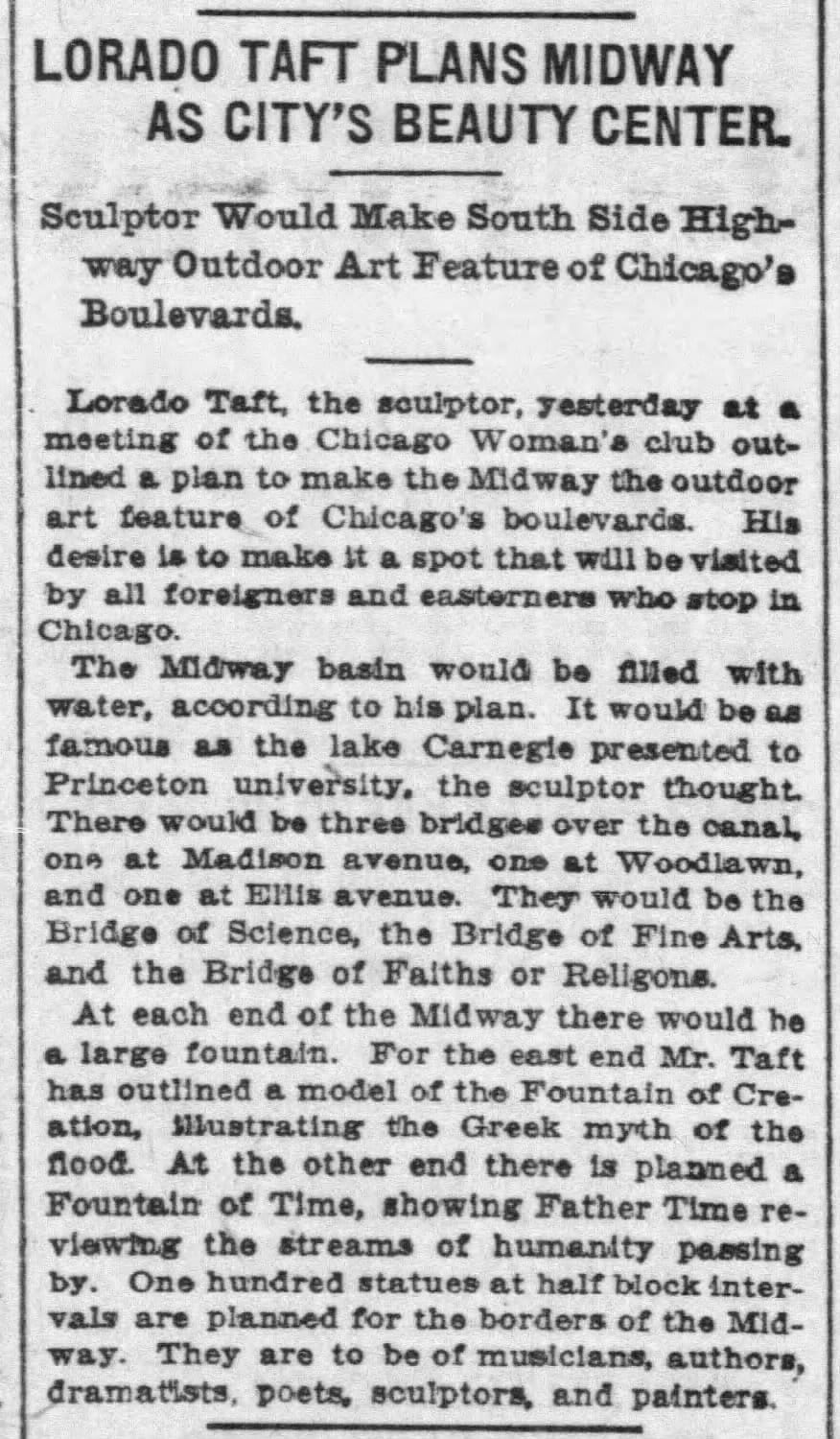

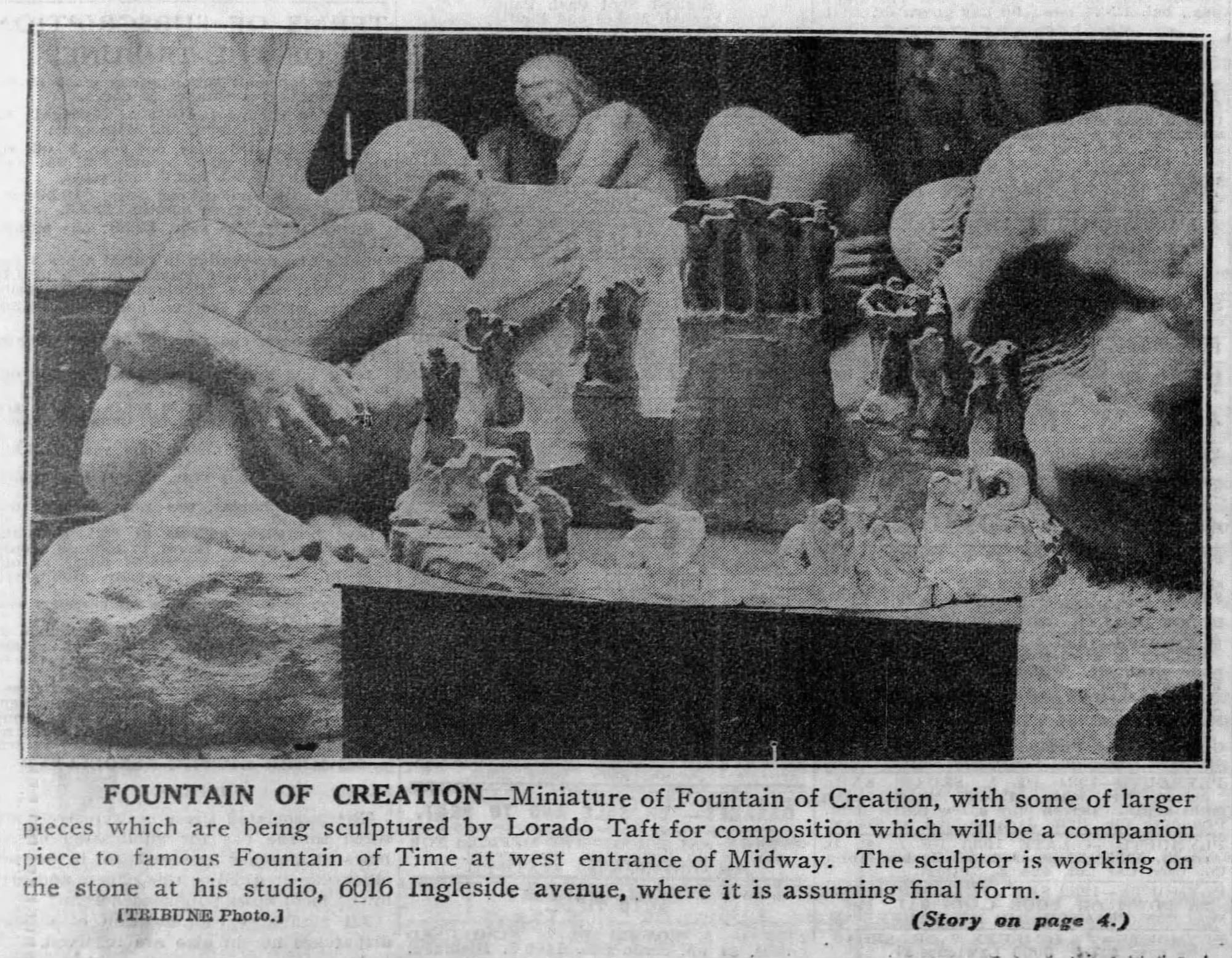

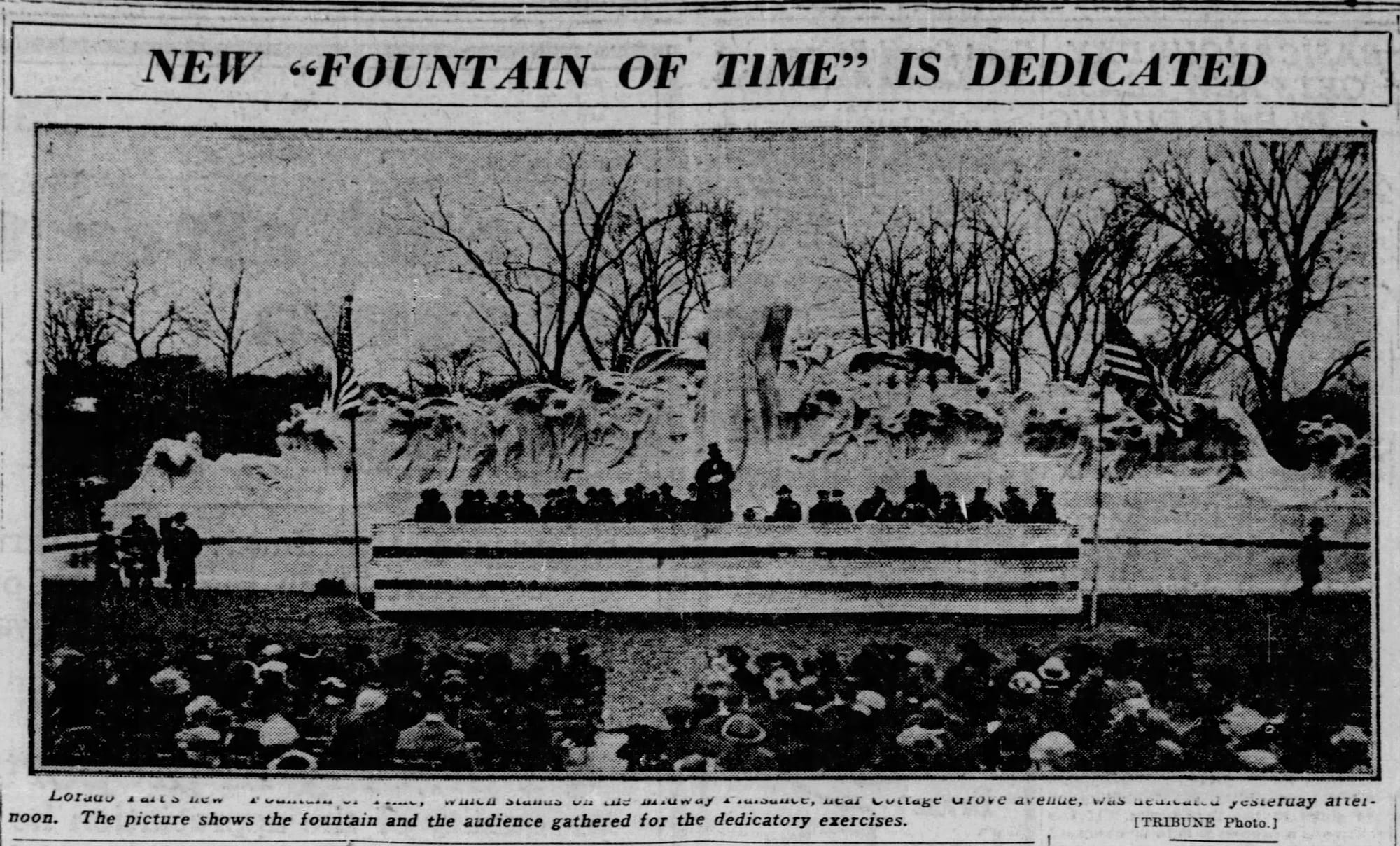

Finished in 1922, the Fountain of Time is the only realized aspect of Taft’s broader plan for the Midway, which envisioned a canal linking the lagoons in Washington and Jackson Parks, crossed by a series of themed bridges, paired with a Fountain of Creation. The canal and the bridges died on the drawing board, and Taft’s fame faded in the nine years between the commissioning of the Fountain of Time and its permanent installation, so a sense of mild melancholy punctured the triumph of the sculpture’s dedication, with Taft saying, “If I have failed, it is my own fault”.

The Fountain of Time represented a novel use of hollow-cast concrete in monumental sculpture—ironic, for an artist whose reputation declined because of the conservatism of his work. That cutting-edge deployment of concrete also unintentionally emphasized the sculpture’s message about the inexorable, devastating passage of time, as pollution, maintenance misfires, and weather degraded the concrete and turned the Fountain of Time into one of Chicago’s most visible and most vexing conservation headaches. After multiple ineffective and damaging restoration attempts, a pioneering (and expensive) effort in the 1990s and the 2000s stanched the decline, hopefully providing a platform for future conservation and ensuring another century of the Fountain of Time.

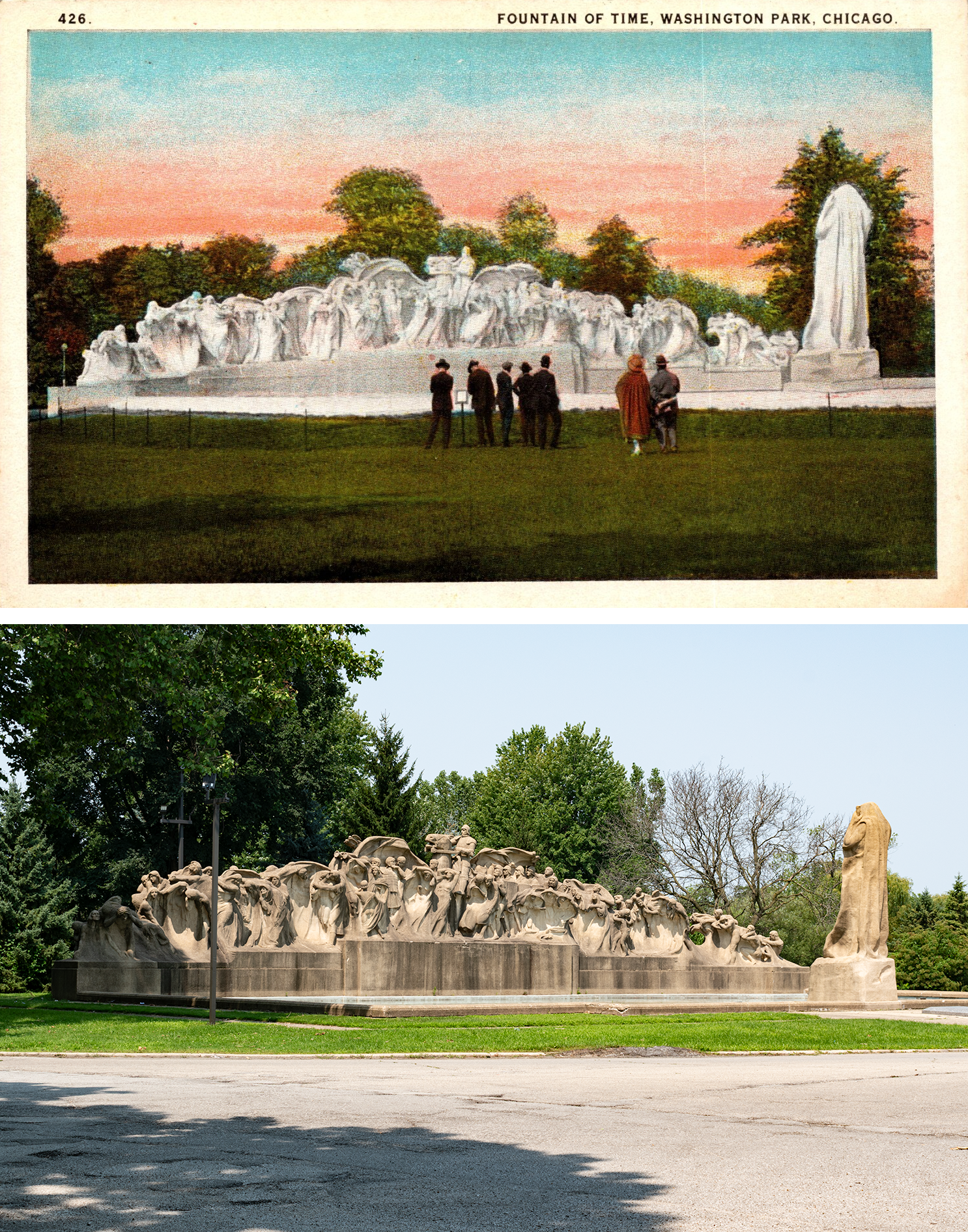

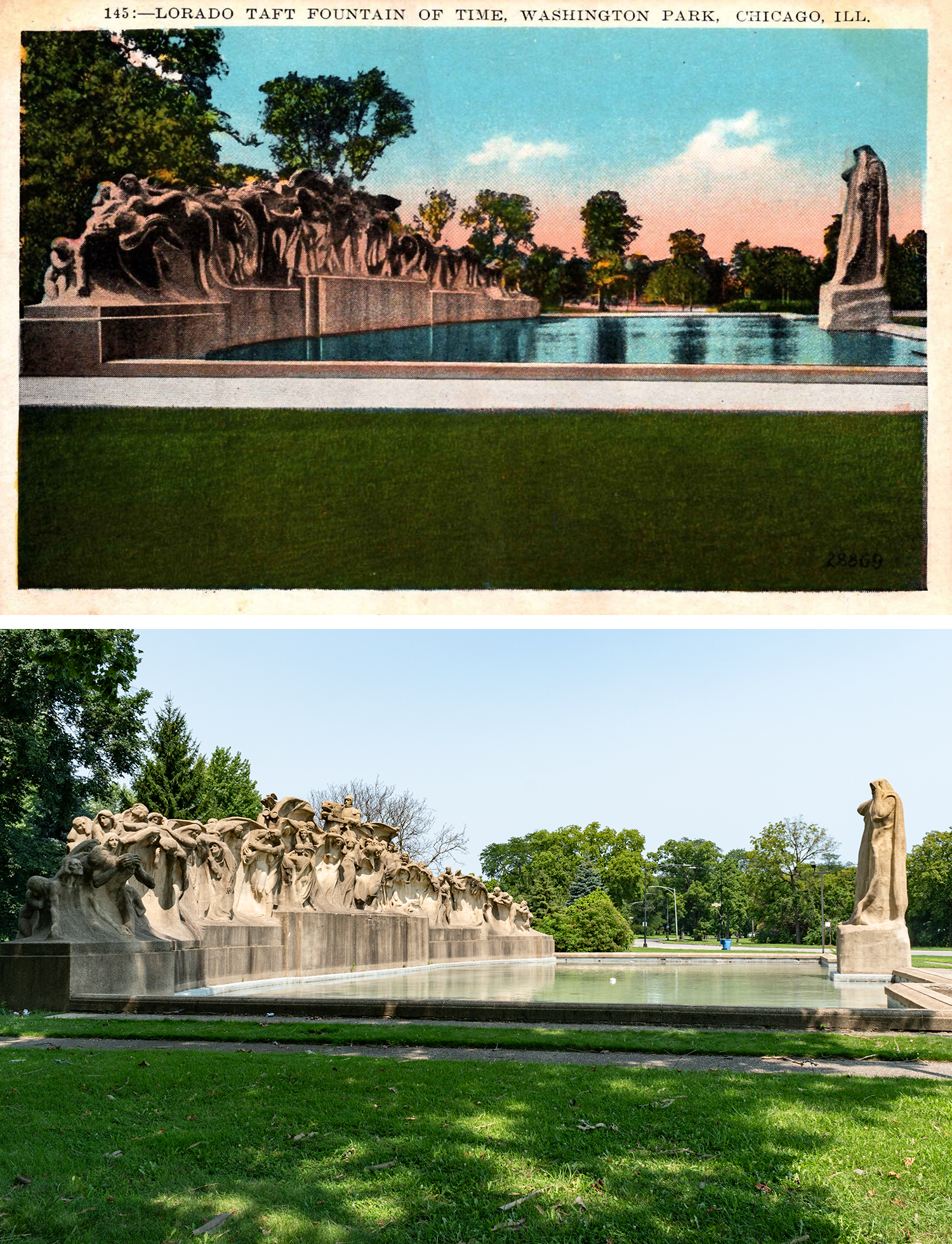

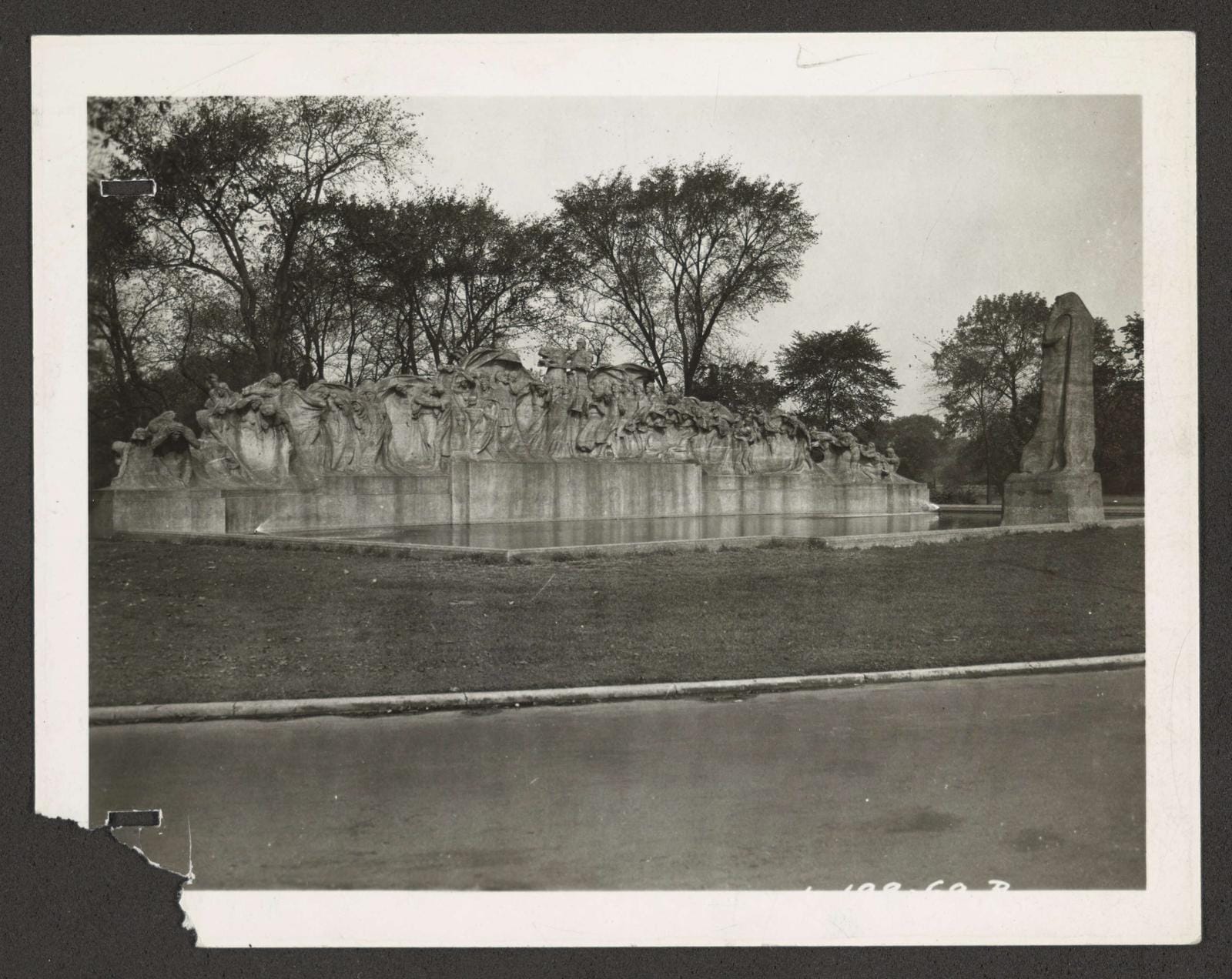

So, what’s changed? More space ceded to cars (of course), a century of foliage growth, and advances in lighting technology, but given the Fountain of Time’s difficulties with decaying concrete and the repeated restorations, it’s interesting how little this scene has changed.

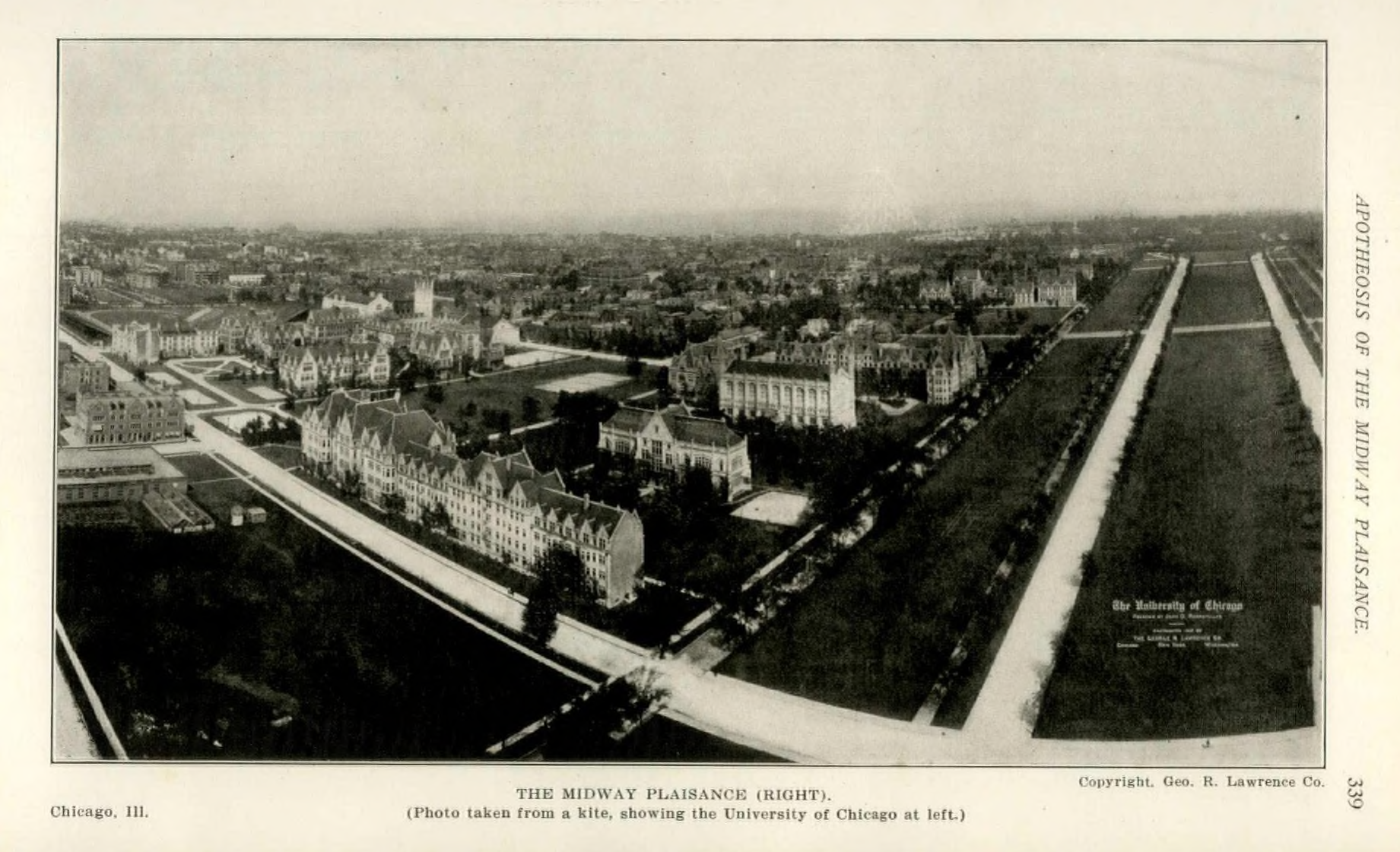

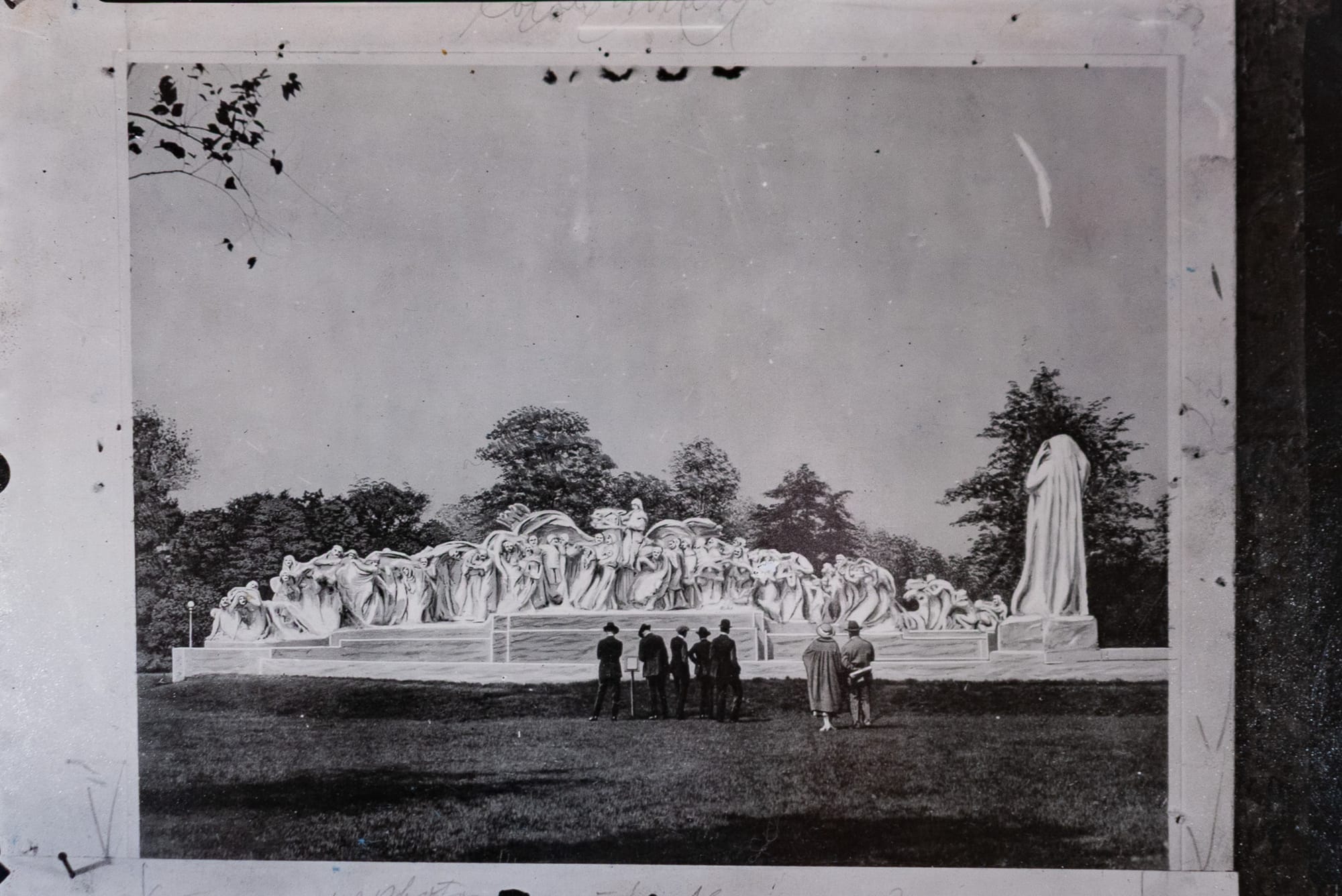

Inspired by Austin Dobson’s poem (although he’d later joke that the couplet was “all I ever read of Dobson”), in 1907 Lorado Taft started workshopping the concept of a procession of people marching past a stylized figure of Time. Ambitious, famous, and with his career nearing its peak, Taft envisioned the Fountain of Time as just one part of a massive project that would—twenty years after the World’s Fair—once again remake the Midway Plaisance, turning it into a giant platform for Beaux Arts sculpture. He wanted to connect the lagoons in Jackson and Washington Park with a canal, creating a need for ornate bridges dedicated to the arts, to science, and to religion, lined with statues in a sort of Hall of Fame, and flanked by the fountains of Time and Creation.

1910, Architectural Record, the Internet Archive | 1913 and 1922 articles about Taft's Midway Plaisance plan | 1935, the Fountain of Creation | 1965, "Boulevard of Broken Dreams", Chicago Tribune | 1913, "Art Chiefs Order Statue", Chicago Tribune | 1913, woman with Time | 1914, Ferguson Fund To Beautify City | 1914, Space in Midway Gifted

The Fountain of Time would be the first step for the rest of the project. To pay for it, Taft tapped a previous patron, the B.F. Ferguson Monument Fund. The Ferguson Monument Fund was a public endowment bequeathed by Chicago lumber baron Benjamin Franklin Ferguson upon his death in 1905. The fund was supposed to be spent on statuary or monuments in public spaces in the city Chicago commemorating American history. The fund was to be administered by the Board of Trustees of the Art Institute of Chicago, but it wasn’t a gift to the Art Institute (something that would become an issue a few decades later, when the Art Institute asked, "can a building be a public monument? can OUR building be a public monument? and basically plundered the fund to pay for the museum's administrative wing [the B.F. Ferguson Memorial Building]).

Taft was the first artist commissioned by the monument fund—which paid for his excellent Fountain of the Great Lakes, completed in 1913—and so he went back to the Art Institute trustees to finance the Fountain of Time.

Notice an issue there?

…the Fountain of Time didn’t commemorate American history or a great American. Well, no worries—Taft and the trustees contrived a connection to a random historic event, deciding that the Fountain of Time commemorated the hundredth anniversary of the Treaty of Ghent and a century of peace between the United States and the United Kingdom.

(It's also barely a fountain—it's a reflecting pool with a sculpture—so they were loose with a few things.)

1913 and 1914, Taft gets the commission | 1913, with plaster casts, the Mentor, the Internet Archive | 1914, clay model, Architectural Record, the Internet Archive | 1921, the International Studio, the Internet Archive | 1920, the installed plaster version

Even split from the rest of Taft’s plans for the Midway, the enormity of the Fountain of Time would’ve exhausted the Ferguson Monument Fund for years, so the trustees took a cautious approach. In 1913, they commissioned Taft to create a plaster model for the site, paying him $10k a year for five years—the equivalent of more than $300k a year in 2026 dollars.

Taft supported this approach for “preventing permanent erection of eyesores while also stirring genuine, widespread popular support for more deserving work”. Even with a studio full of “White Rabbits” (Taft’s crew of mostly-female studio assistants) and years of modeling work completed before he even had someone to fund it, the Fountain of Time was such an ambitious piece it took seven years before Taft’s studio finished the plaster version, which was installed on the Midway in 1920.

Impressed with the temporary version, the fund trustees voted to pay for a permanent one, but the Fountain of Time was so monumental that materials for a lasting sculpture turned into an issue. Taft originally planned on granite, switched to Georgia marble, and even contemplated various metal options, but the project was so impossibly large that carvers refused to even quote a price.

1922, formwork and falsework, Concrete, the Internet Archive | 1924, Atlas Portland Cement Company Catalog, the Internet Archive | 1925, Atlas Portland Cement Ad, House Beautiful, the Internet Archive | 1922, Chicago Tribune | 1930, Chicago Collections

Help for the artist came from an odd source—the Federal Bureau of Standards, the predecessor to the current National Institute of Standards and Technology, recommended Taft connect with John Earley, who’d developed groundbreaking techniques in exposed aggregate concrete for architectural and decorative purposes. Taft was more open to material innovation than his Beaux Arts style suggested—a decade earlier, he had used cast concrete for a 48-foot-tall Native American sculpture near his artists’ retreat in Oregon, Illinois—and he hired Earley's studio to work on the sculpture.

The Earley Process, which John Earley had first deployed at scale for Meridian Hill Park in Washington, D.C., used buff-colored concrete with exposed quartz-inflected aggregate to create a polychromatic effect. They estimated a marble version of the Fountain of Time would’ve cost upwards of $300k—nearly $6m in 2026 dollars, if Taft could have even found someone to take the project—whereas Earley’s studio accomplished this work for only $45k.

The hollow-cast concrete Fountain of Time was made using a 4,500 piece mold. Renowned architect Howard Van Doren Shaw designed the reflecting pool. The permanent Fountain of Time was dedicated in 1922, to mostly positive reviews.

That said, 15 years had passed since Taft first started playing with the concept, and nine years since the Ferguson Monument Fund officially commissioned him for the project. The world had changed. By the early 1920s, Taft’s classicism was falling out of style, in favor of Art Deco, abstraction, and early modernism. His pull diminished, by the time the permanent Fountain of Time was dedicated in 1922, Taft’s broader plan for the Midway was dead, although he continued to advocate for it and even worked on models for the Fountain of Creation. Taft’s time, like many of the figures in his monumental sculpture, had passed.

1938, Chicago Collections | 1955, Architectural Forum, the Internet Archive | 1956, Chicago Collections | Undated, 1950s, Chicago Collections | Undated, 1950s, Chicago Collections | 1958, Mildred Mead, Chicago Collections | 1965, Facelifting, Chicago Tribune | 1966, re-dedication, Chicago Collections | 1983, Chicago Tribune

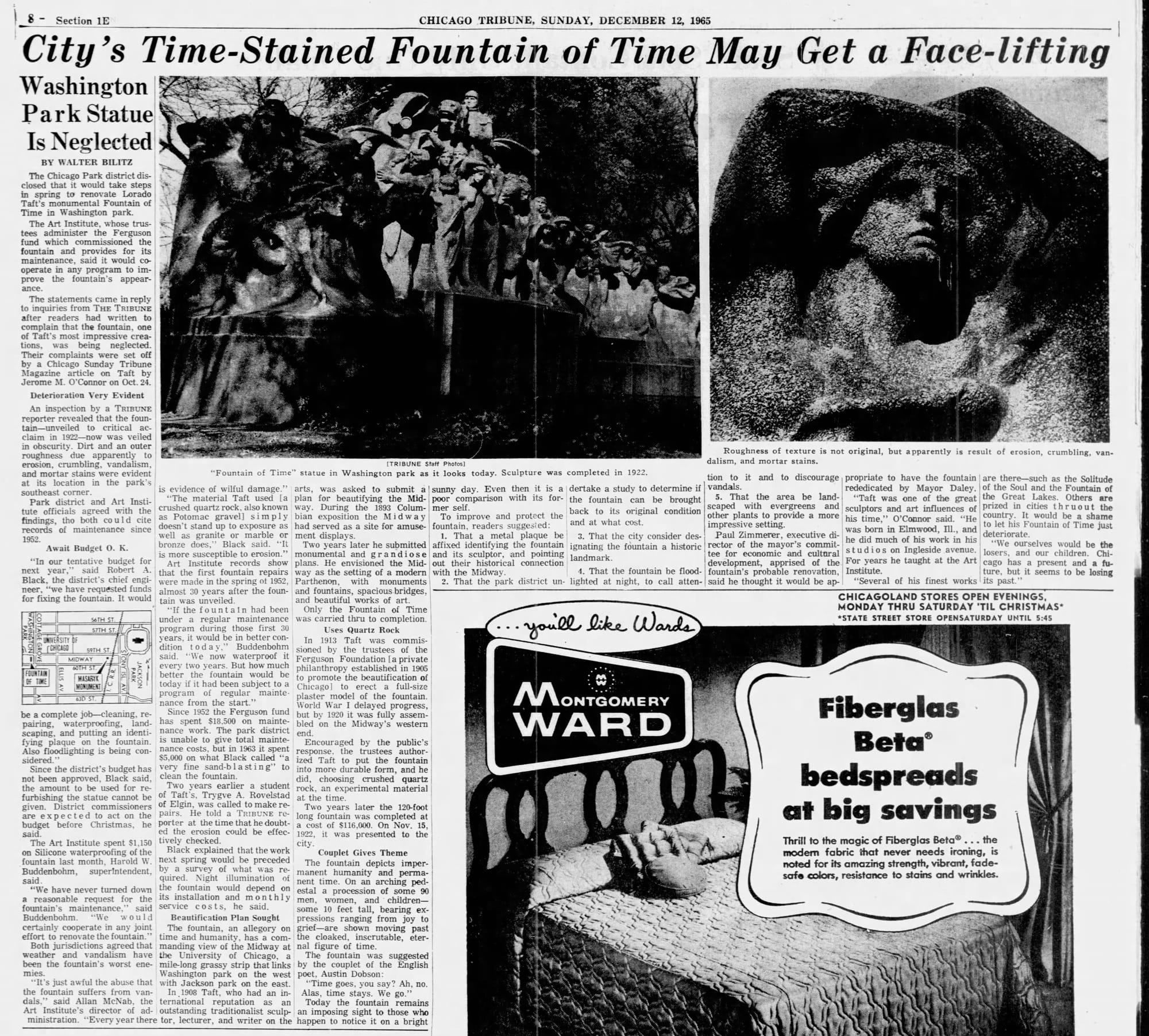

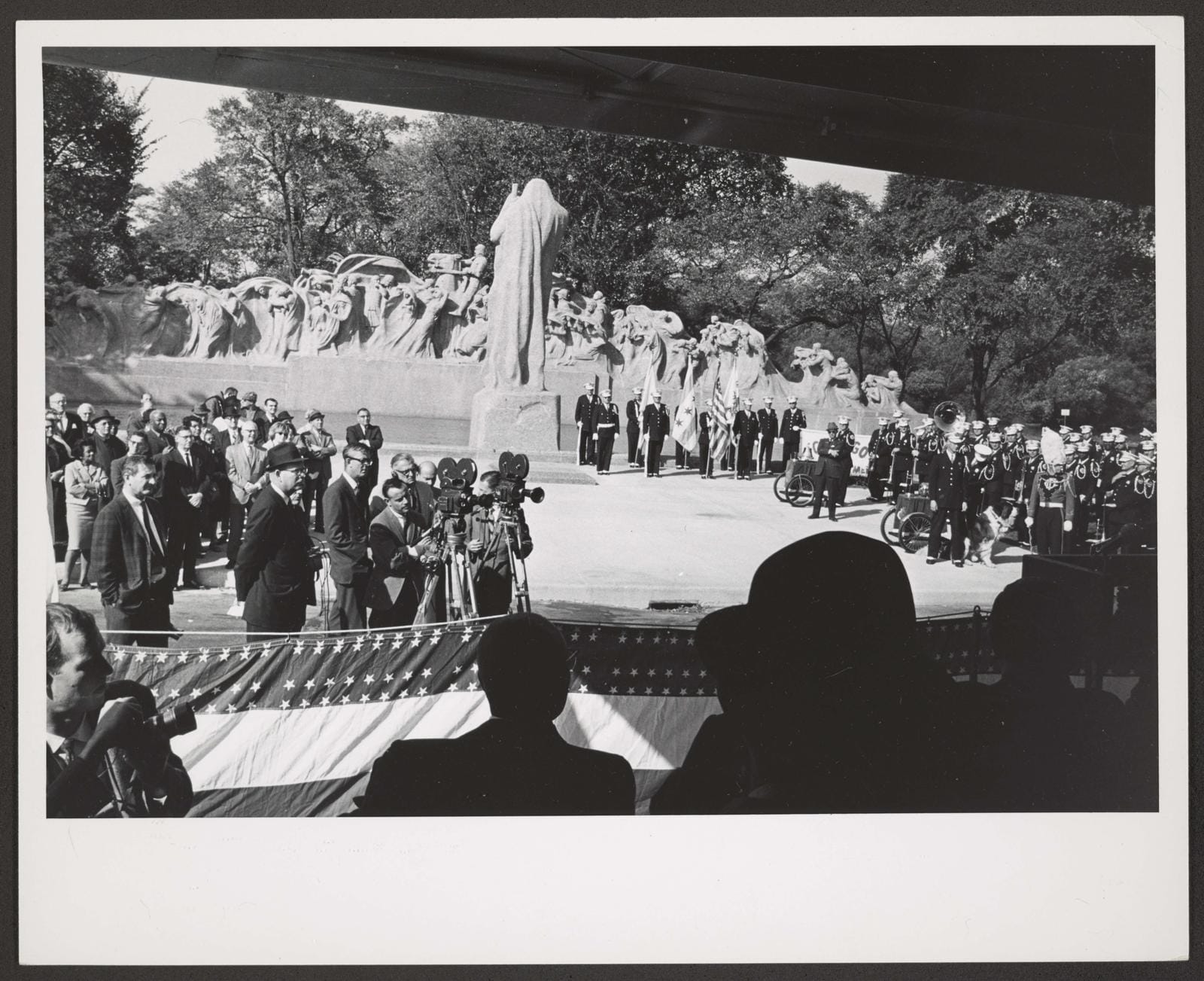

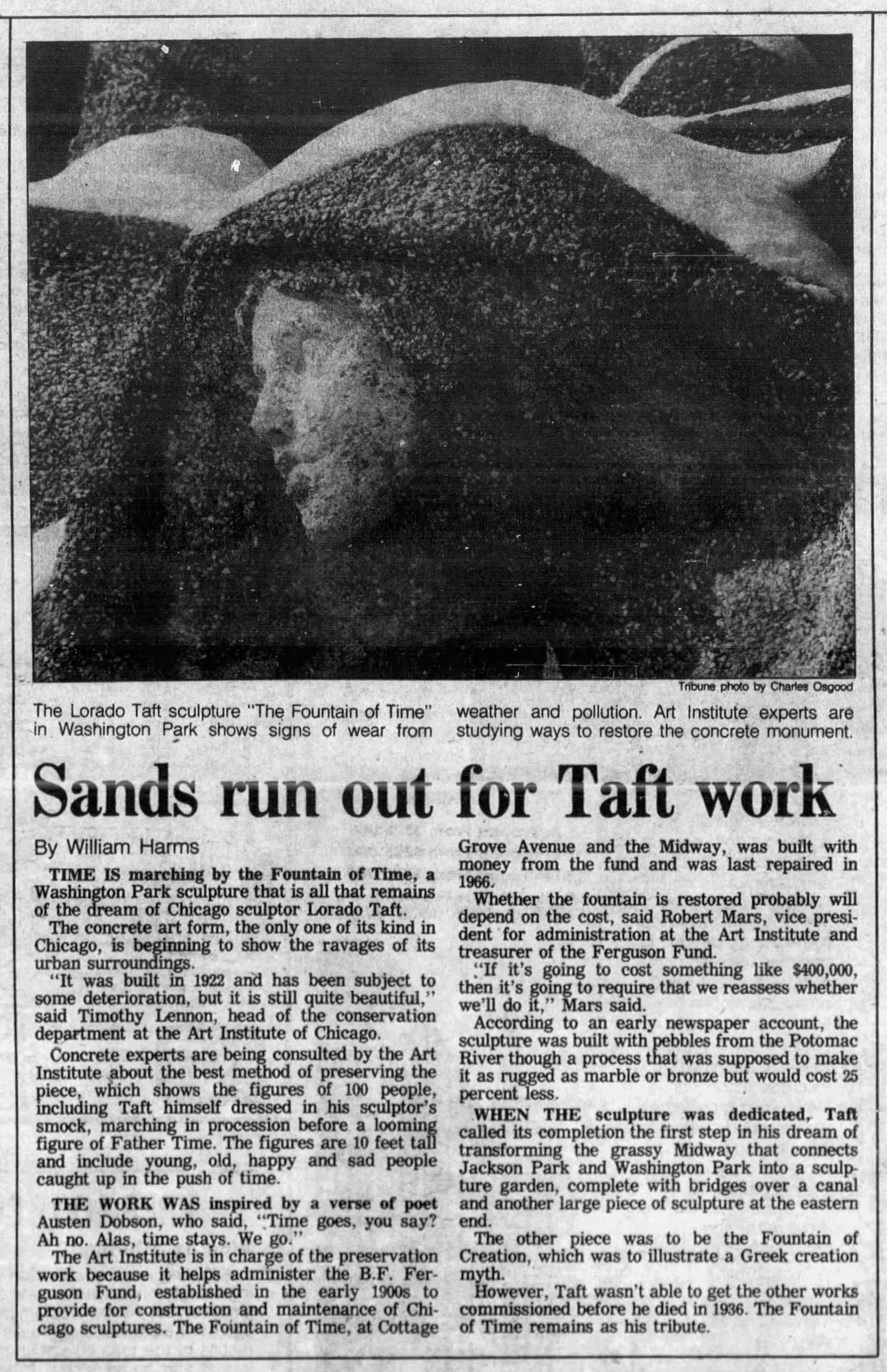

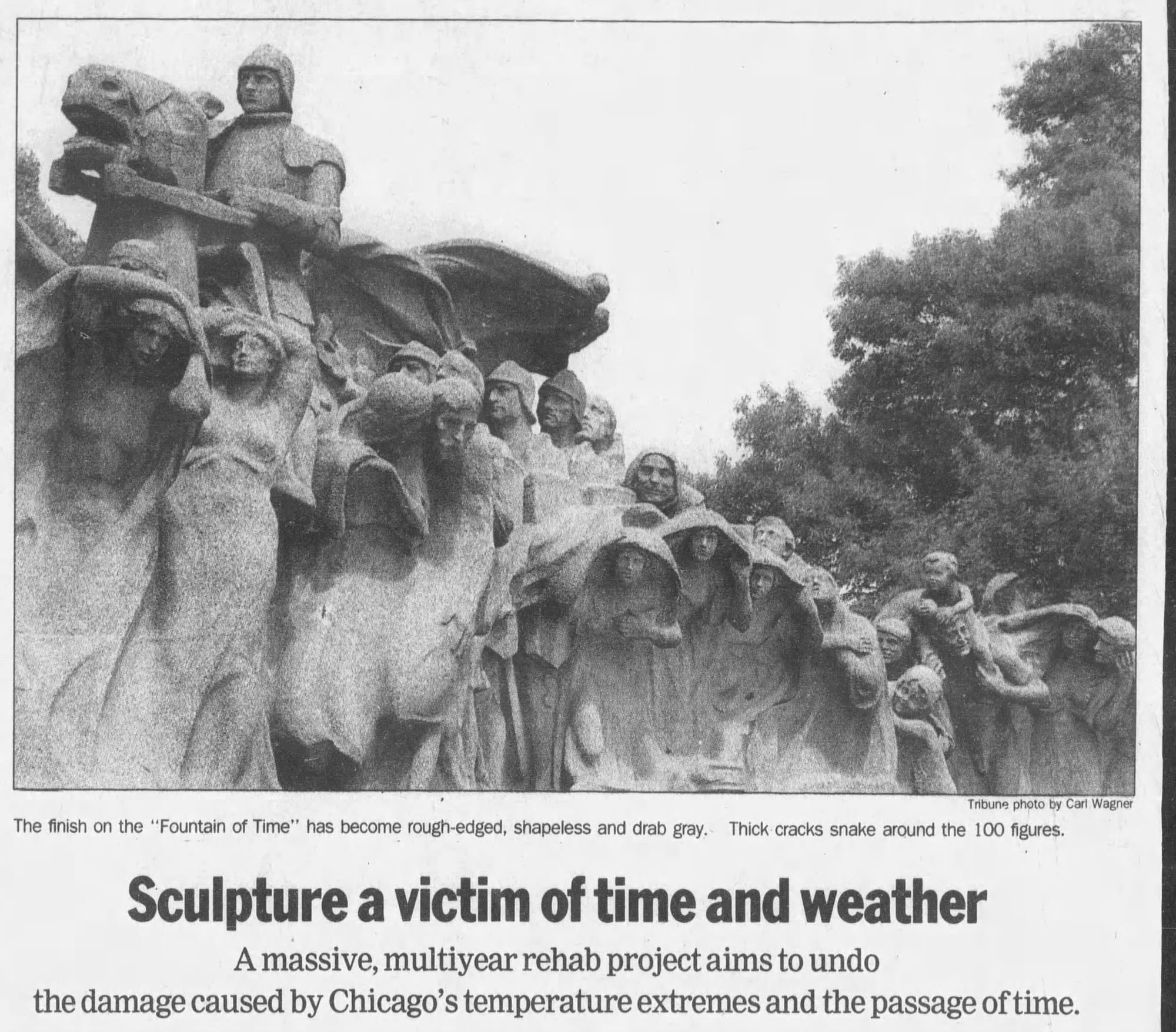

There’s a reason, though, you don’t see much public sculpture made out of concrete—turns out the details don’t always age well. Acid rain, the freeze-thaw cycle, and vandalism took its toll on the Fountain of Time. The cement paste that bound the concrete dissolved over the years, accentuating the exposed aggregate and giving the figures a pebbly, decaying appearance, and by the 1950s the reflecting pool was drained. Architectural concrete was a new material for art conservationists, and restoration attempts in the 1930s and 1950s made things worse—one figure lost its nose. Mayor Daley presided over a re-dedication in 1966 after a major restoration attempt, but it failed to fix the fundamental problems and by the 1980s the Fountain of Time was almost beyond saving.

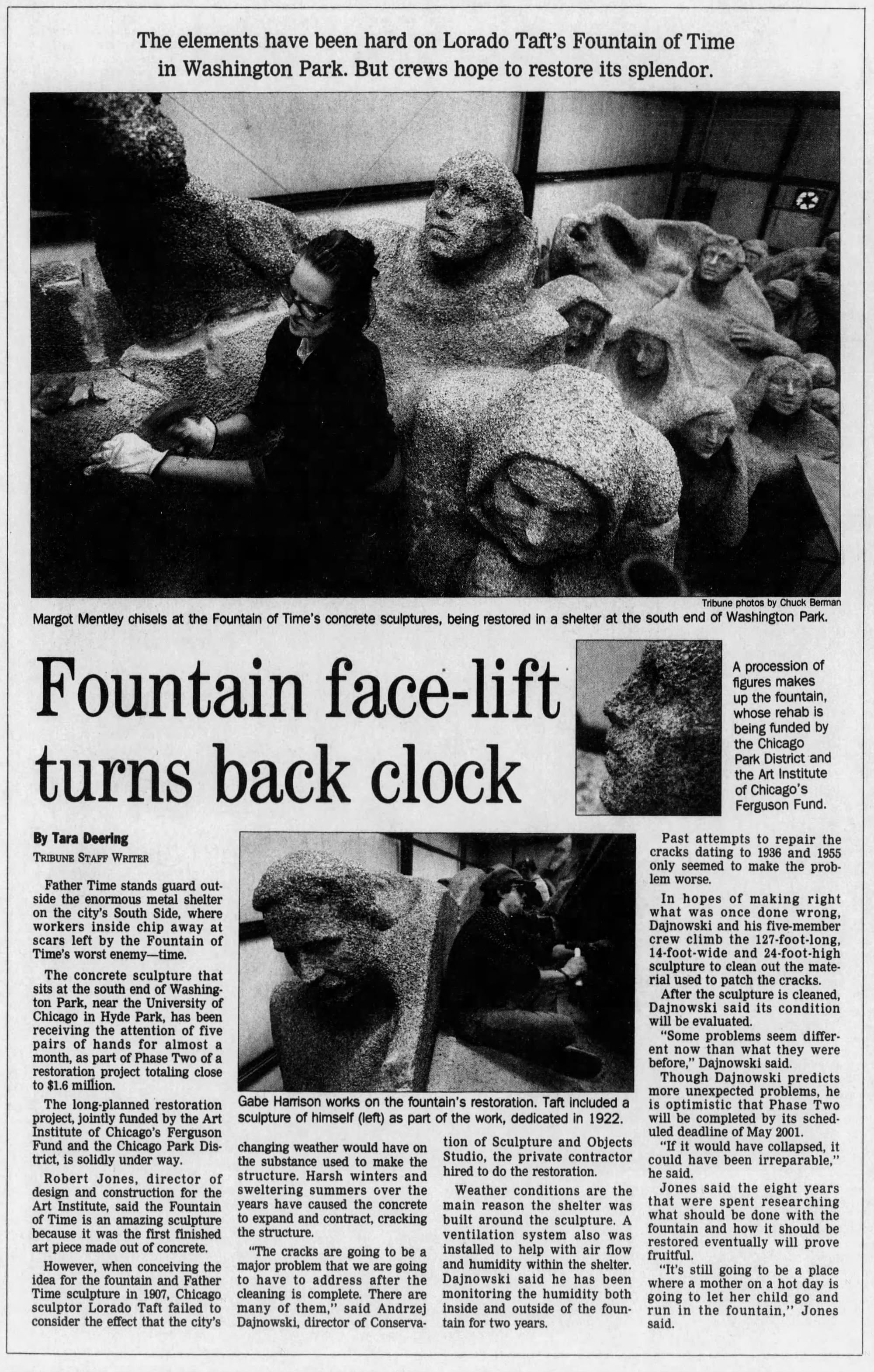

In addition to the specific conservation challenges of restoring a unique monumental sculpture, there was the added question of who would pay for an expensive and experimental conservation process. The B.F. Ferguson Monument Fund, which still exists, the Chicago Parks District, the University of Chicago, some other big donor? Finally, in the early 1990s, the Ferguson Fund, the Parks District, and the Art Institute hammered out an agreement and hired conservator Andrzej Dajnowski to lead the rescue project.

1997 articles about the effect of time and weather on the Fountain of Time | 1999 article on the restoration

Over the next decade a bunch of different conservators, architects, and engineers would work on the massive project—BauerLotaza, Wiss, Janney, and Elstner, Conservation of Sculpture and Objects Studio, Takao Nagai Associates, among others—which would pioneer new methods for concrete conservation. They installed ventilation systems, fought over the appropriate amount of restoration to maintain authenticity of the degraded figures, and—after years of searching—finally found a matching aggregate for Earley’s Potomac River pebbles in a Chicago gift shop, sold as part of a Bonsai kit. Besides restoring the concrete sculpture itself, the restoration project aimed to create a platform for future conservation efforts as well. This was one of those projects that was highly influential in a hyper-specific field, and more than two decades later their work still basically holds up (as far as I can tell).

A masterwork by one of Chicago's most famous artists, a monument to ambition, disappointment, and decay, there's poetry in the Fountain of Time itself becoming a case study for the eroding effects of time on public sculpture.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Washington Park MPS National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

- Public sculptor: Lorado Taft and the Beautification of Chicago by Timothy Garvey

- “Time and Tide: Restoring Lorado Taft’s Fountain of Time: An Overview.” by Barbara Hall and Robert Aaron Jones

- "New Art of Concrete" an address by Lorado Taft

- "Building the Fountain of Time" by John J. Earley

- "The Fountain of Time" in the Architectural Review

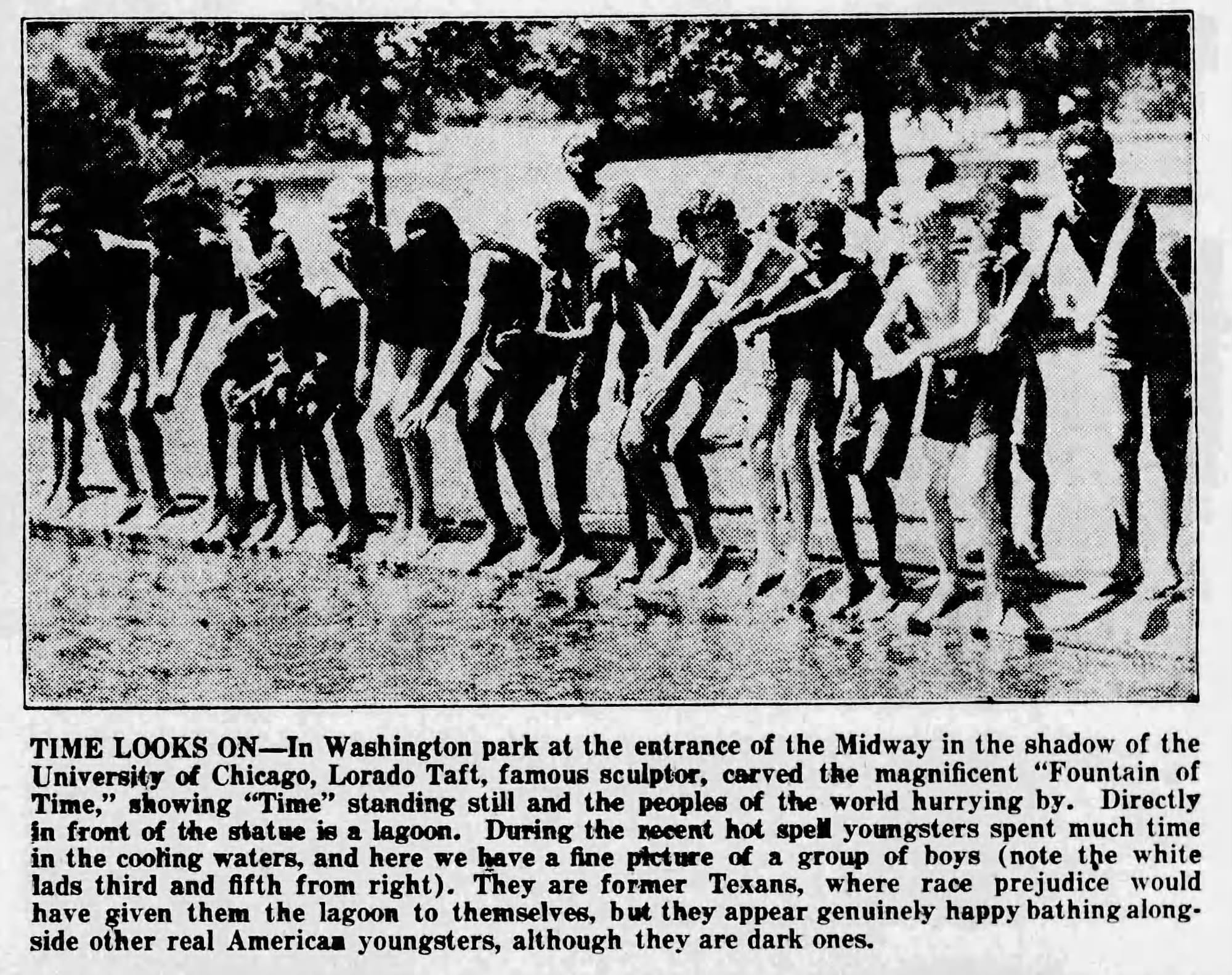

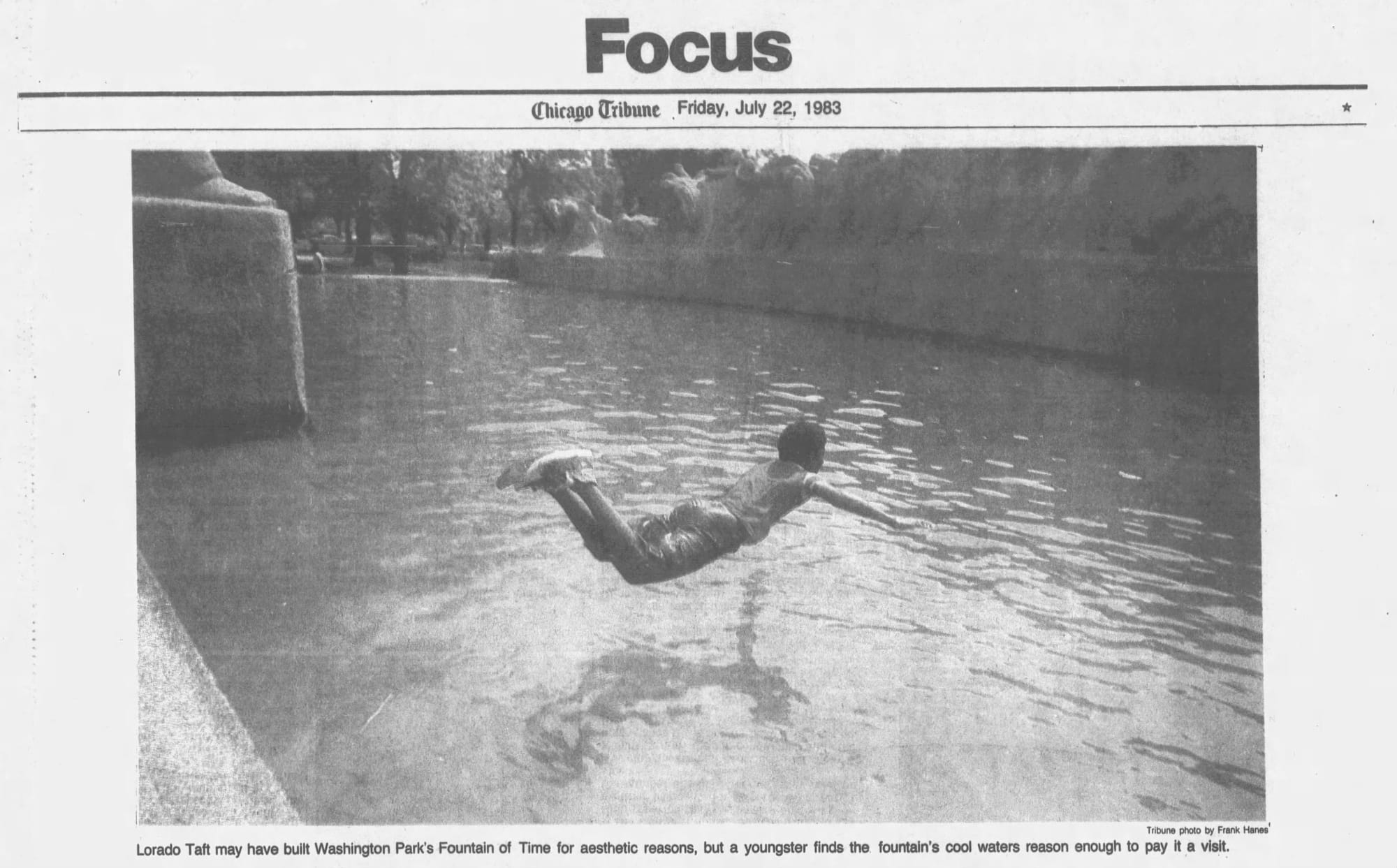

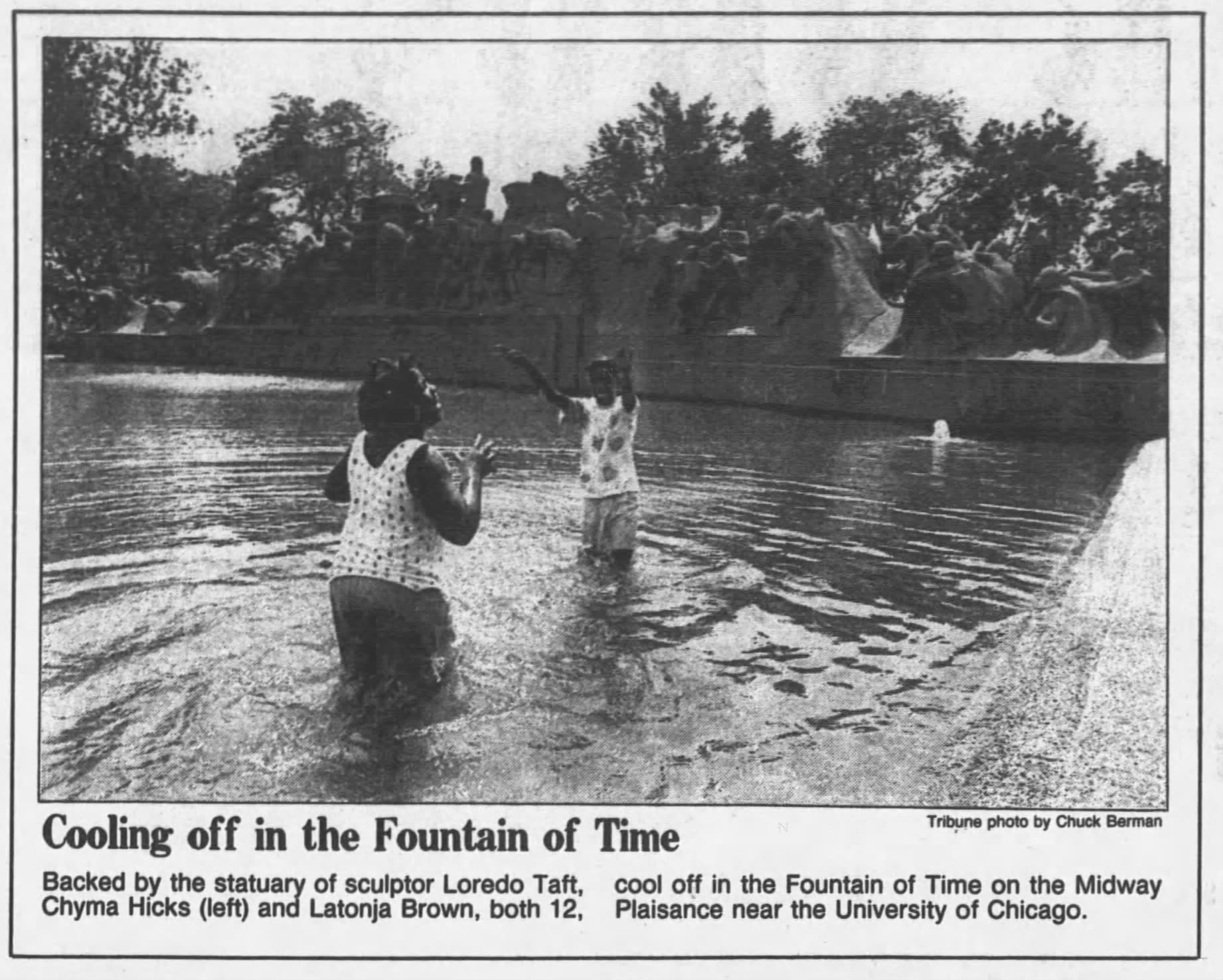

From the 1930s through the 1990s, when it was filled (which, for decades it wasn't) the reflecting pool was occasionally a place for locals to cool off.

1932, Chicago Defender | 1983, Chicago Tribune | 1990, Chicago Tribune

Pretty sparse folder in the Curt Teich Archive at the Newberry Library, this was the only thing in it.

Thought it was kind of fun, the random ads it appeared in in the 1920s.

1921 ad for Hyde Park | 1921 car ad

This is where I took the photo from.

Member discussion: