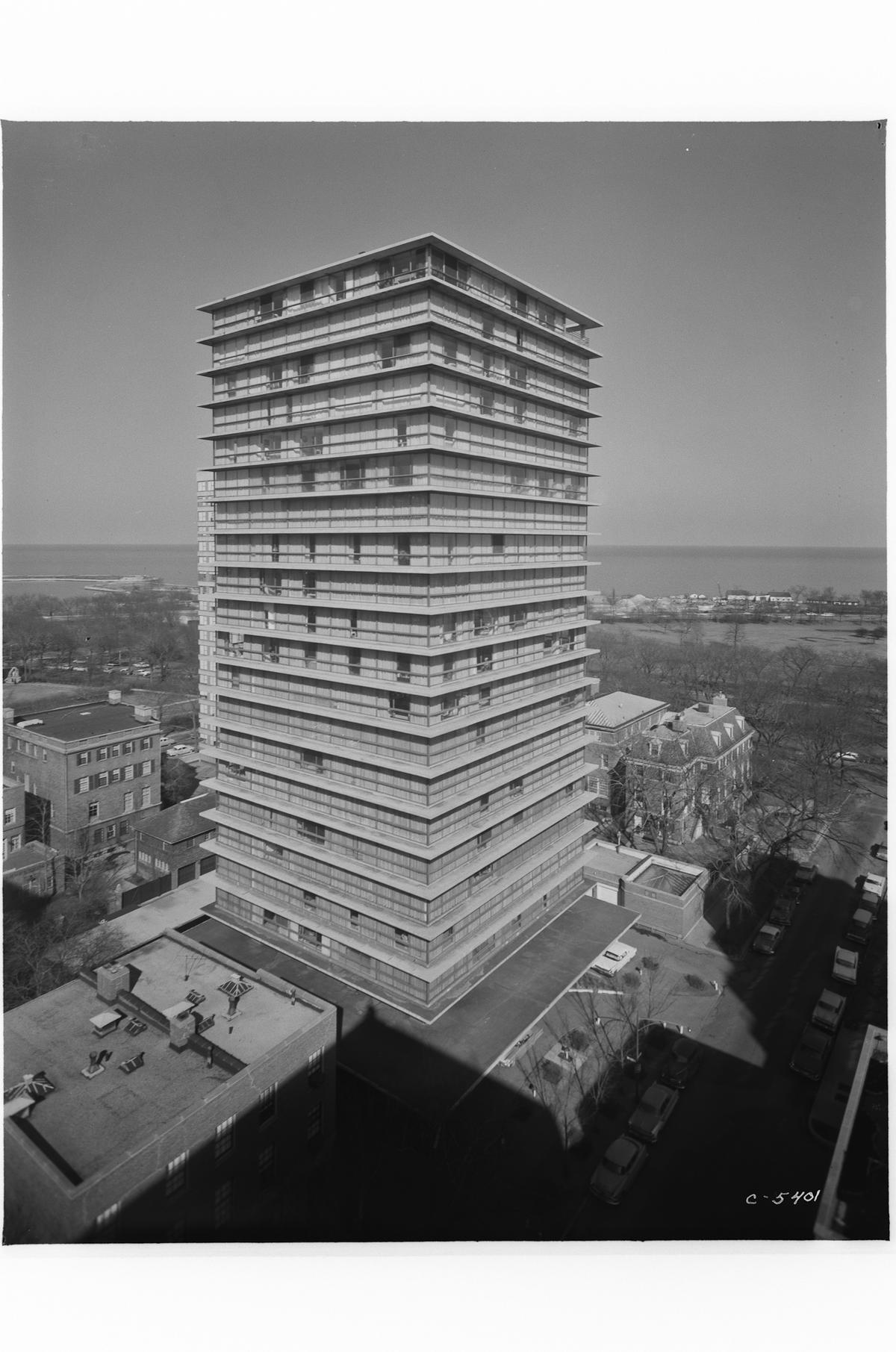

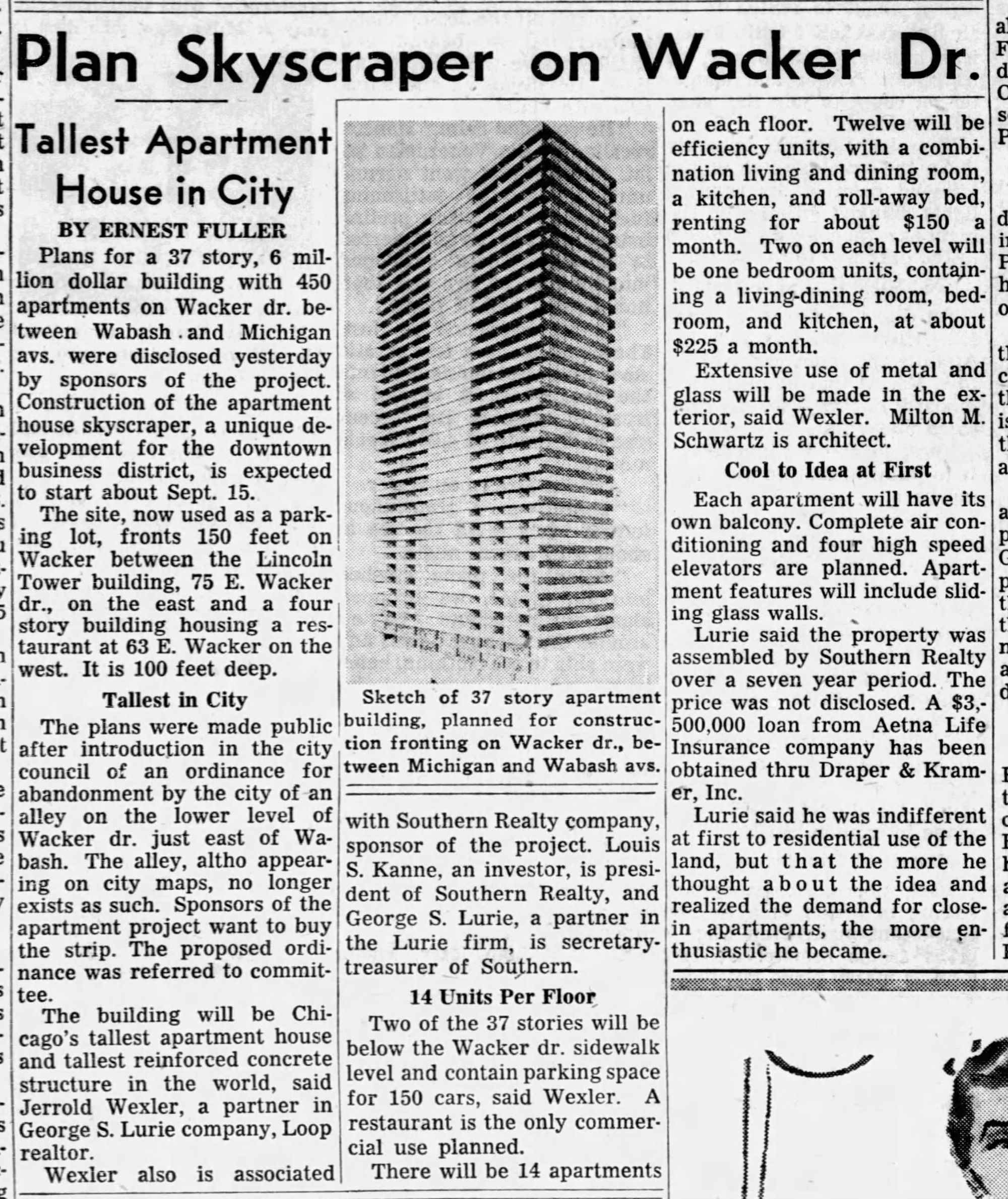

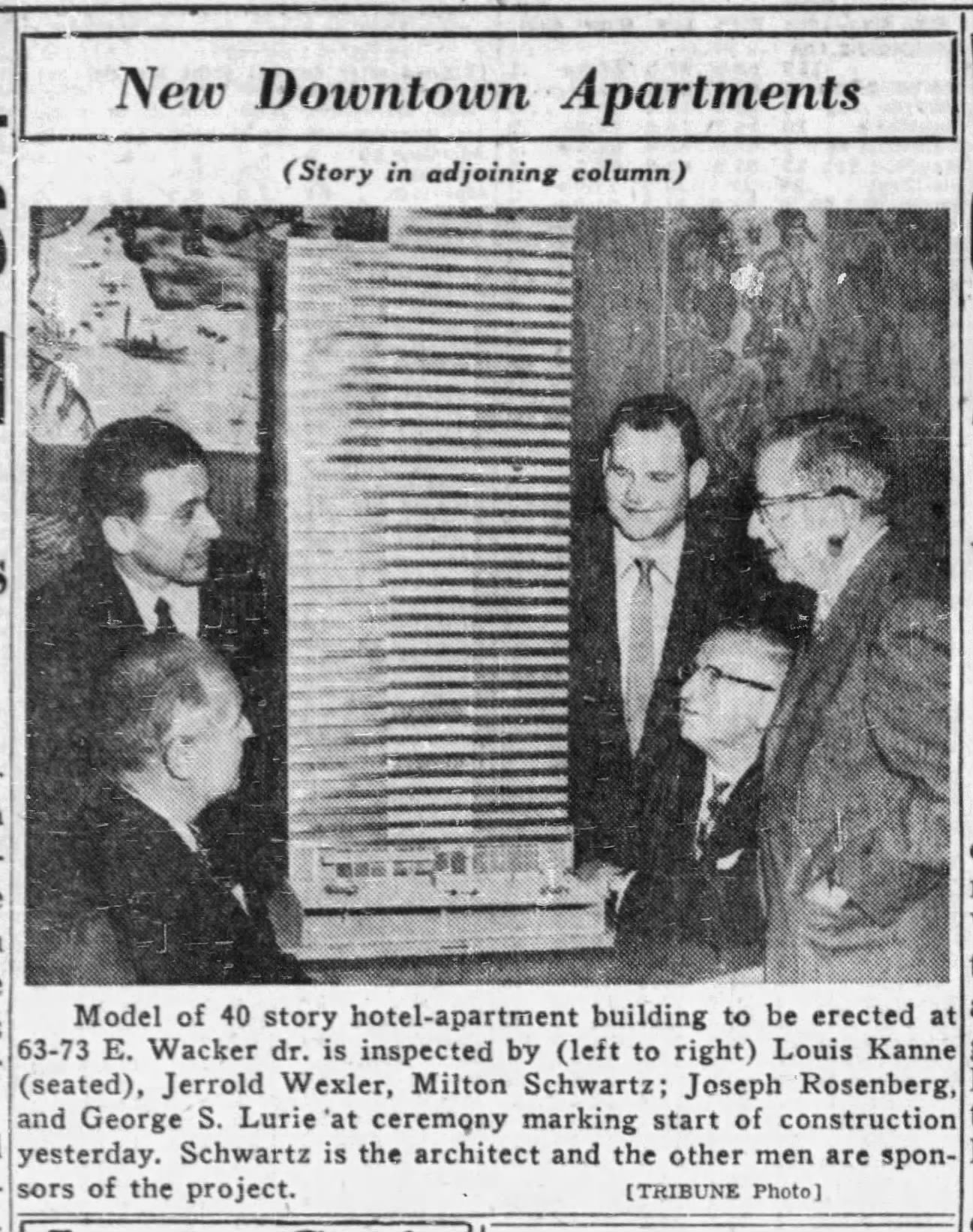

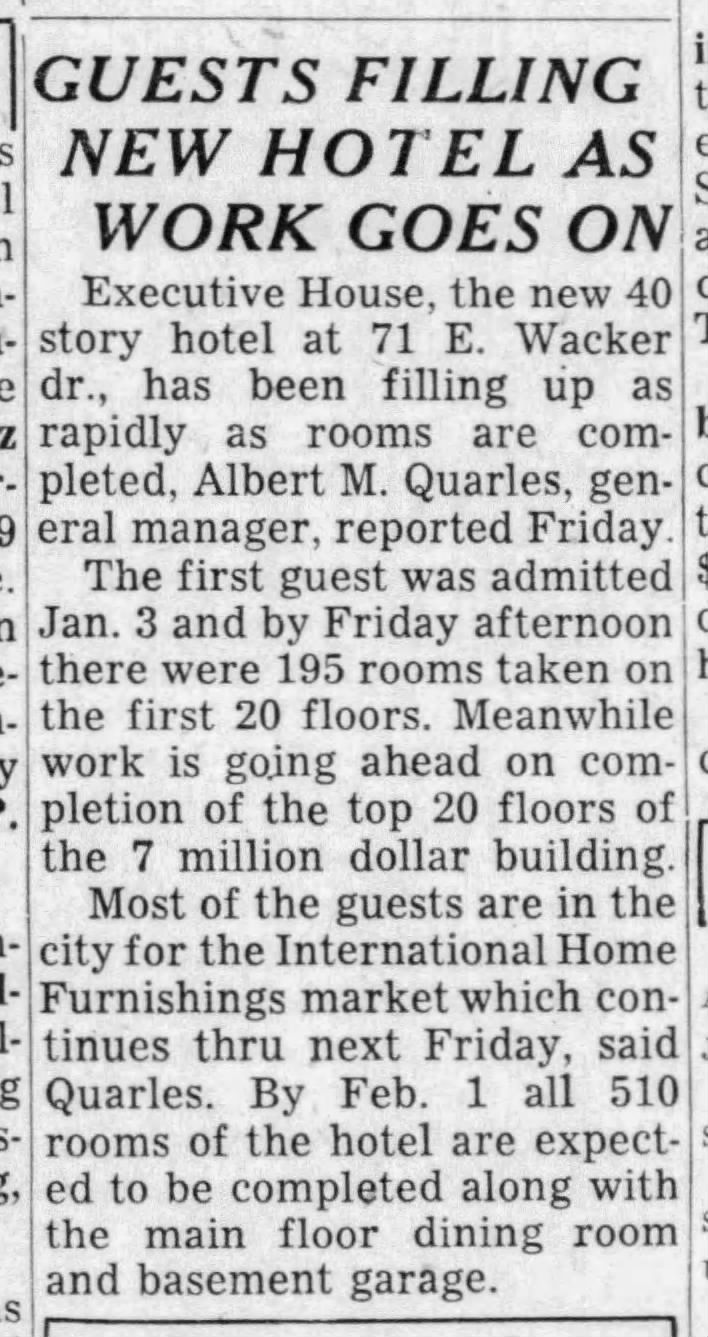

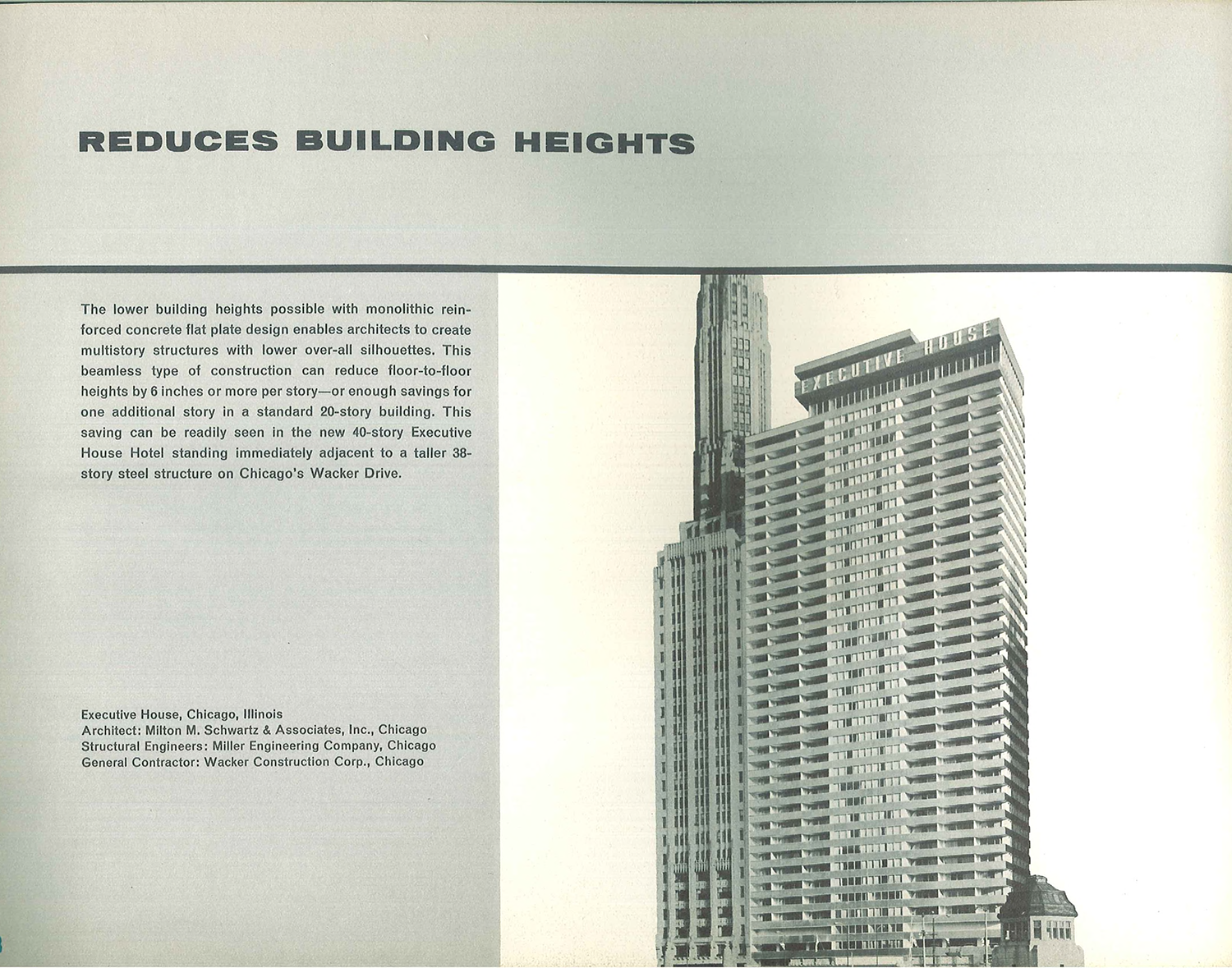

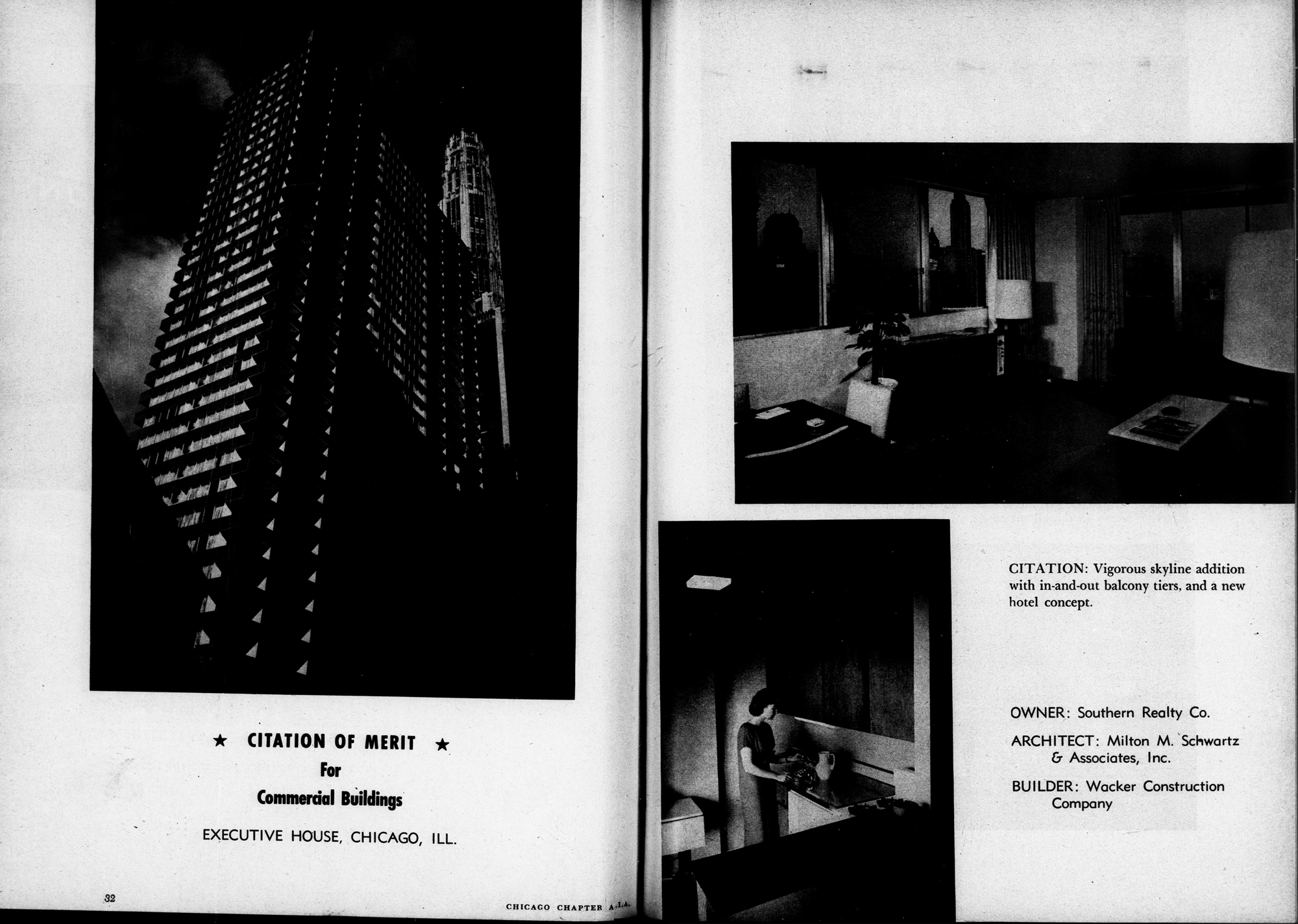

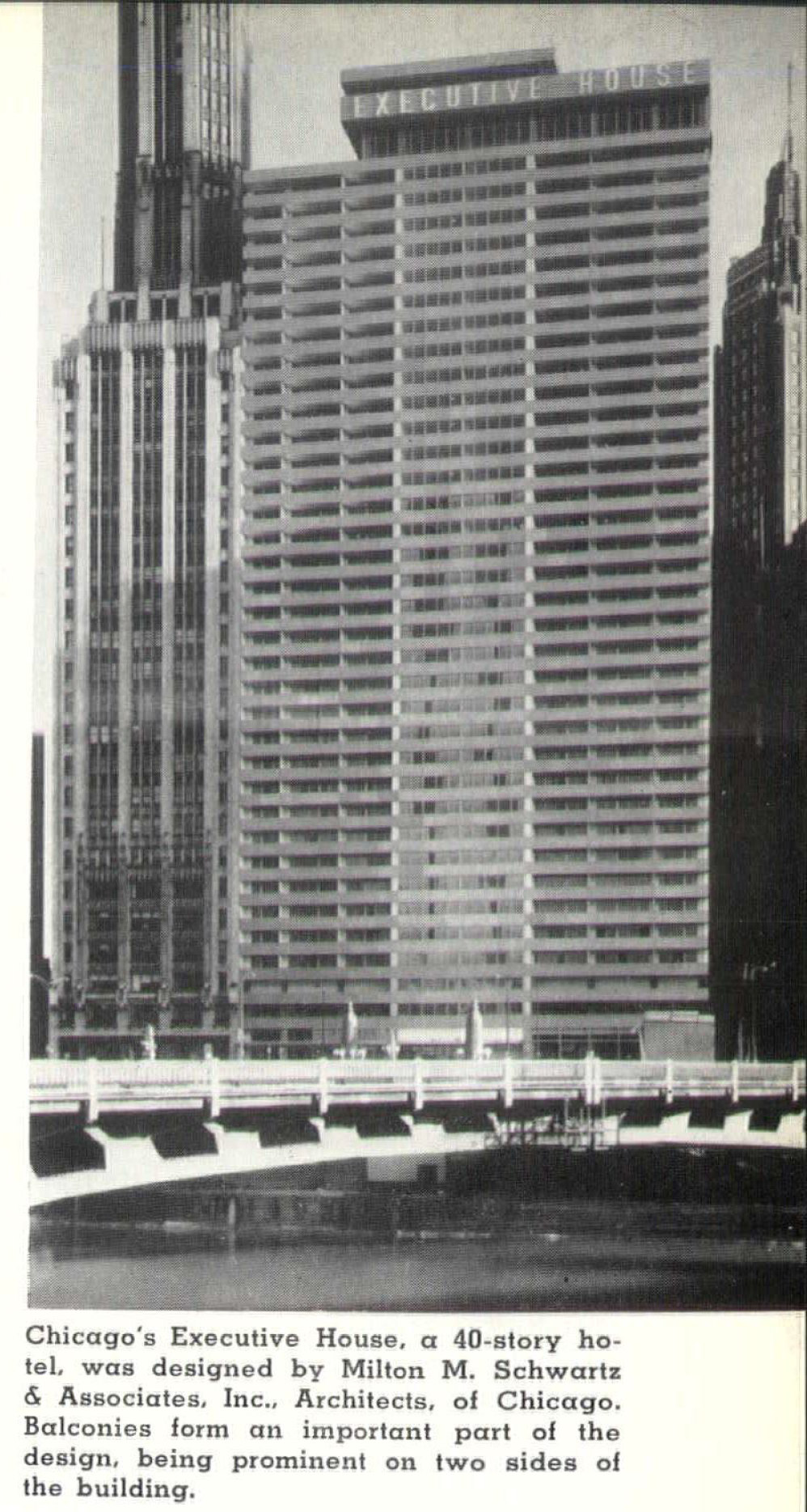

A record-setting engineering feat and still looking fresh nearly 65 years later, 71 E. Wacker is a quiet star on Chicago's riverfront. Look at that slick stainless steel and glass with the alternating horizontal bands–would you have ever guessed it was completed in 1959? Designed by architect Milton Schwartz and engineer Henry Miller, the Executive House was the tallest reinforced concrete building in the US when it was built, and the first high-rise hotel built in Chicago since the Great Depression.

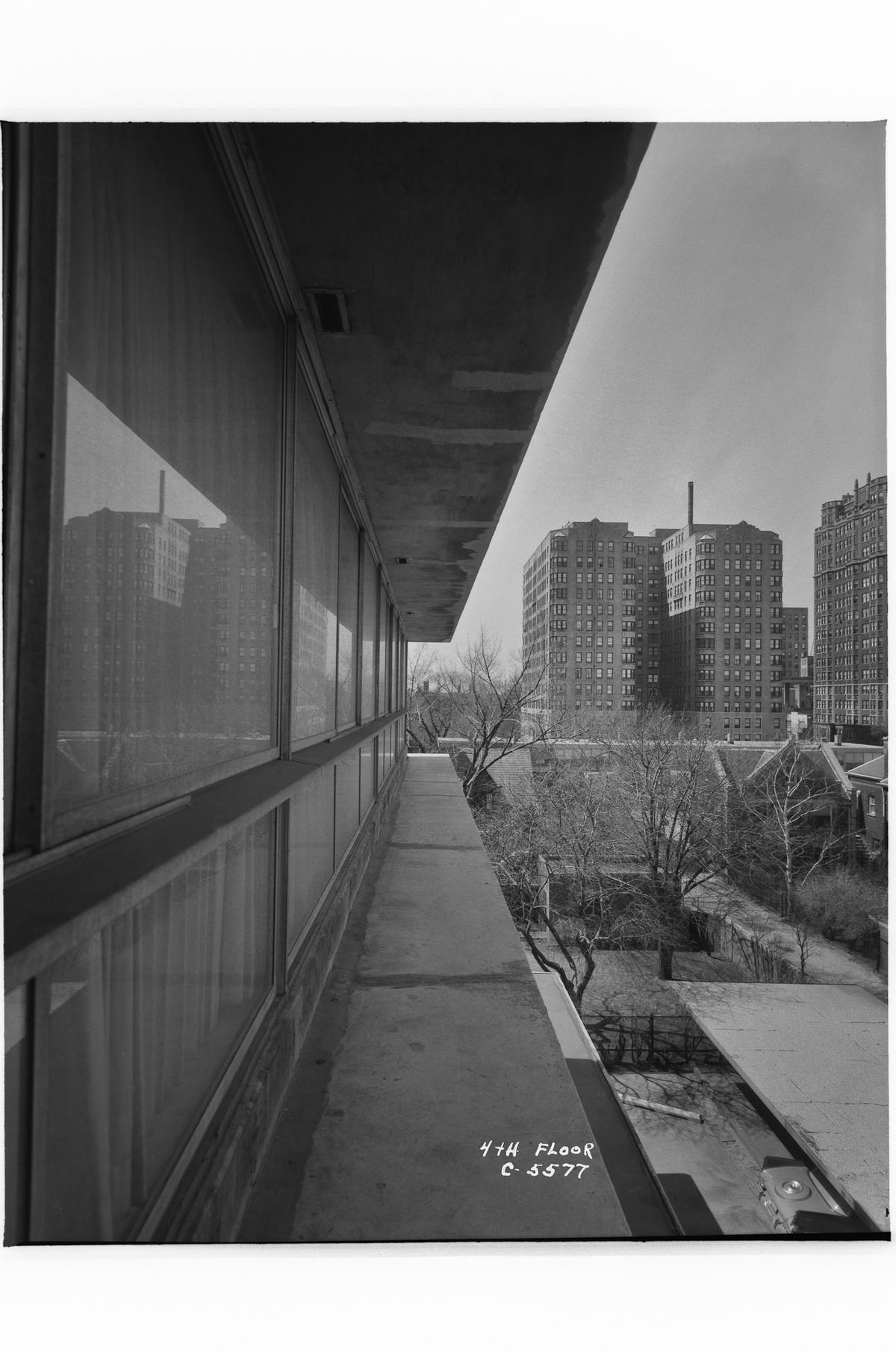

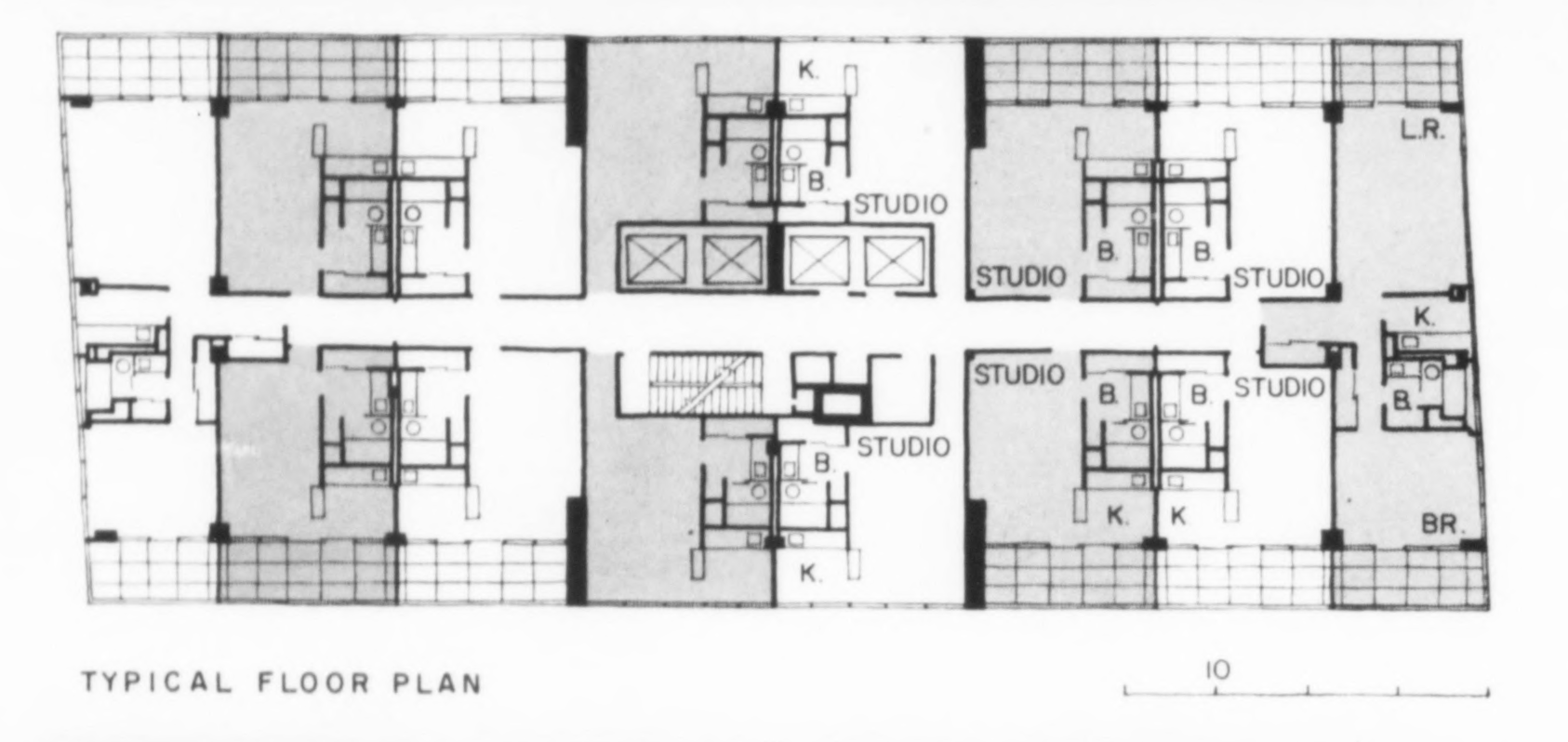

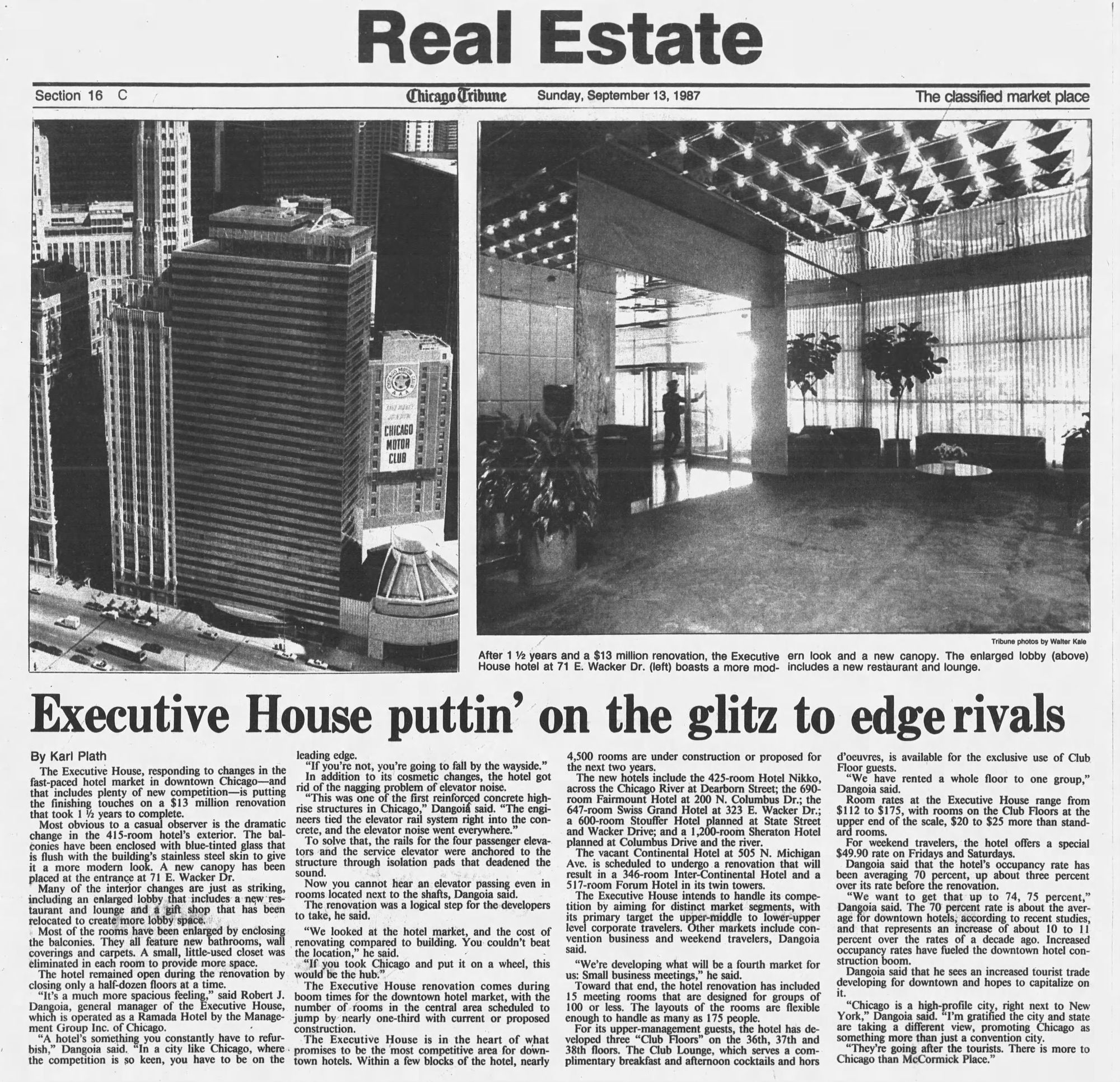

Changes: balconies? Balconies! I was surprised to see them, but the Executive House was ringed with inset balconies until a 1986 renovation glassed them in. A remnant from the initial plans to market the building as apartments, turning them into year-round hotel room square-footage was presumably an easy decision. The area in front of the hotel is lusher nowadays after Wacker Drive and the riverfront were reconfigured in the early 2000s, with green terraces stepping down to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. The third major change is the glassy, contextual addition to the London House that completed the Wacker Drive street wall. Slipped into the little gap between London House and Mather Tower and designed by Goettsch Partners, it was completed in 2016.

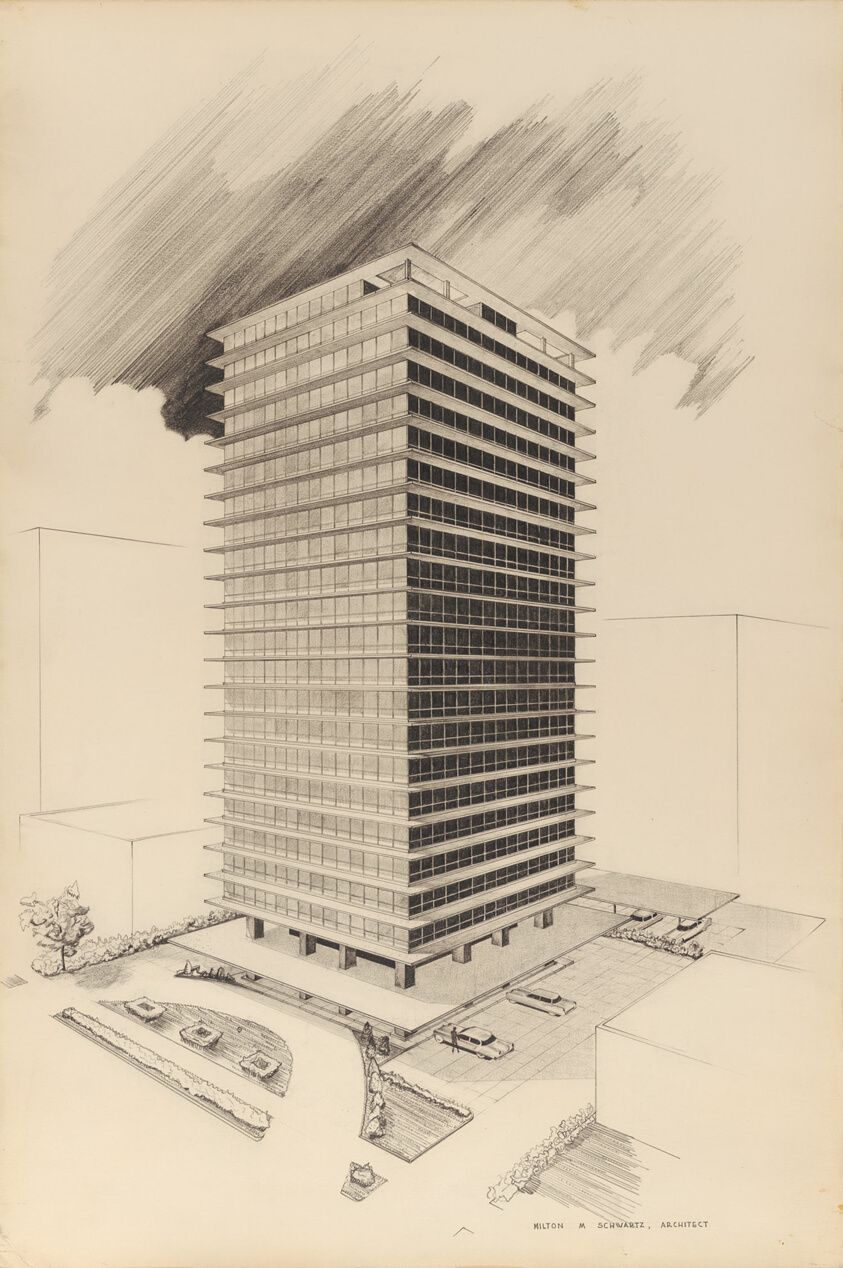

Architect Milton Schwartz first envisioned the Executive House as a circular, steel frame apartment tower. …it ended up a rectangular, reinforced concrete hotel.

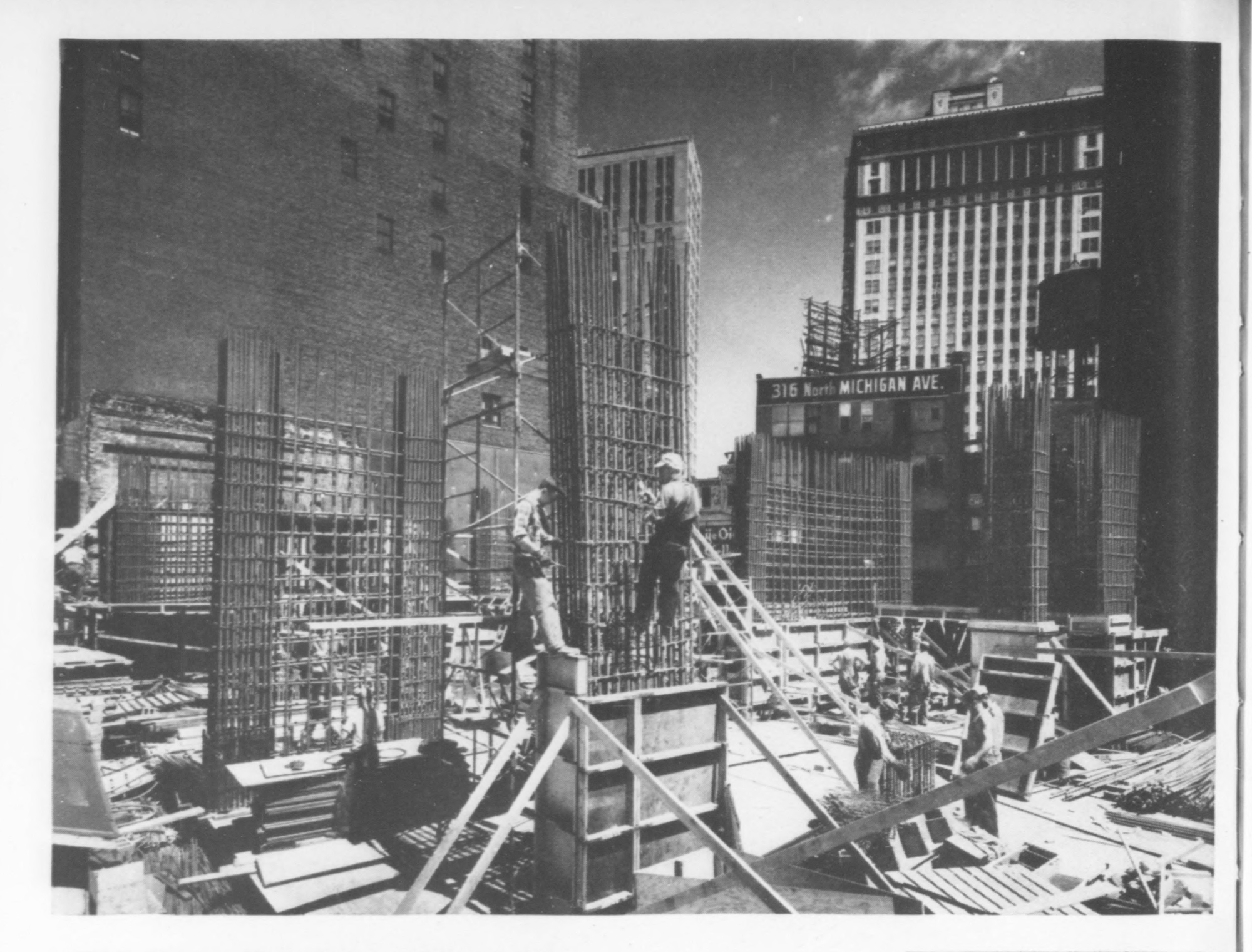

Then again, in the 1950s Schwartz envisioned everything circular–his first proposals for 320 W. Oakdale, a brilliant modernist apartment building in Lakeview, also called for a cylindrical tower. Bankers didn’t find his out-of-the-box ideas financially persuasive, so to secure financing the Executive House ended up rectangular–Milton must’ve been STEAMED when Bertrand Goldberg got Marina City built across the river only a few years later. Steel prices spiked in the mid-1950s so, with Schwartz’s firm experienced working with concrete, they pivoted from steel frame to reinforced concrete construction. Rather than pure apartments, they decided the Executive House would be an apartment hotel, with a minority of the hotel rooms available to rent long-term.

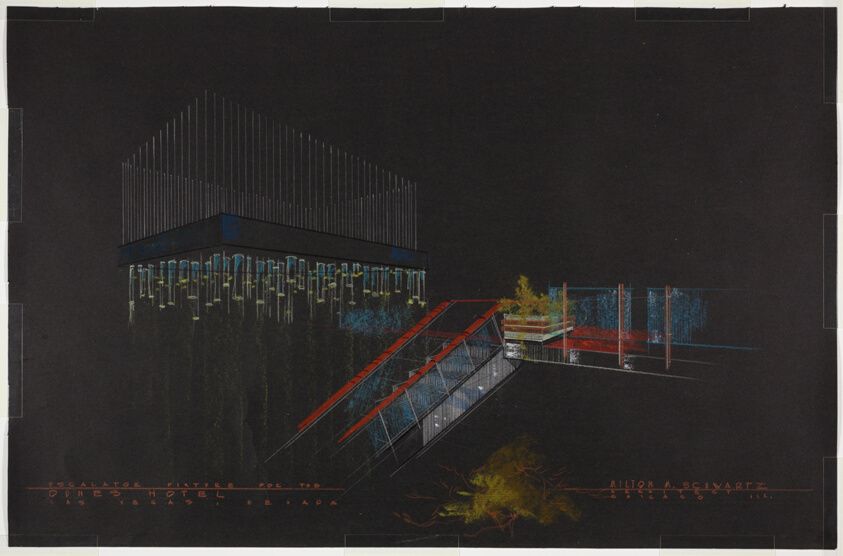

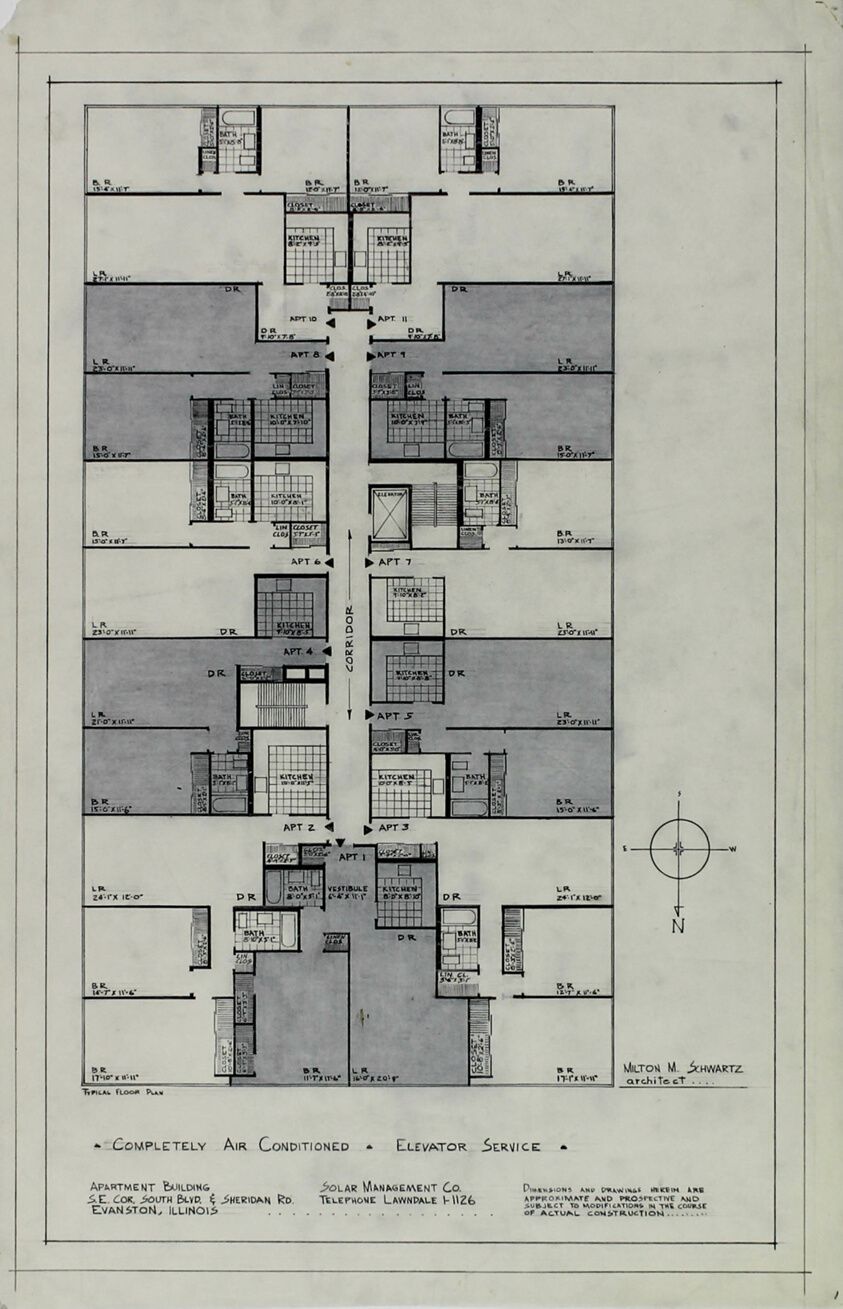

Milton Schwartz had an interesting career. Also a developer and a contractor at a time when architects considered that a professional breach, Schwartz learned to work with concrete through projects he won as a contractor at Great Lakes Naval Base after the war. The first building Schwartz’s firm designed might be their best–320 W. Oakdale, with its dramatic overhangs and floor-to-ceiling glass giving it a stack of modernist pillows kind of vibe. His firm also designed the Constellation in Gold Coast, the Statesman in Edgewater, and the Sanjil in Evanston (now the Shoreview apartments). After that run designing modernist apartment towers around Chicago, he spent years working on the Dunes hotel and casino in Las Vegas.

The most renowned alum from Schwartz’s firm was undoubtedly Stanley Tigerman, who worked there for a bit after leaving the Navy while the firm was working on the Executive House. Tigerman didn’t have much nice to say about Schwartz–although he notoriously didn’t have nice things to say about almost anyone–saying in Schwartz’s obituary, "I think Milt tried to be a good architect. He was not a commercial hack. He had a desire to do well." Damning with faint praise, but I think Tigerman was being unnecessarily rude here–the Executive House, on its own, is something to be proud of.

When it opened in 1959 the Executive House was the tallest reinforced concrete building in the US. Where were the taller ones globally? Argentina, Spain, and–the tallest–the Banespão in São Paulo, Brazil. Less than two years later it was surpassed domestically by the National Bank of Georgia Building (now One Park Tower) in Atlanta. The Executive House is one of a handful of buildings in Chicago to have held this title, including Marina City, the 1000 Lake Shore Plaza Apartments, Lake Point Tower, Water Tower Place, and 311 Wacker.

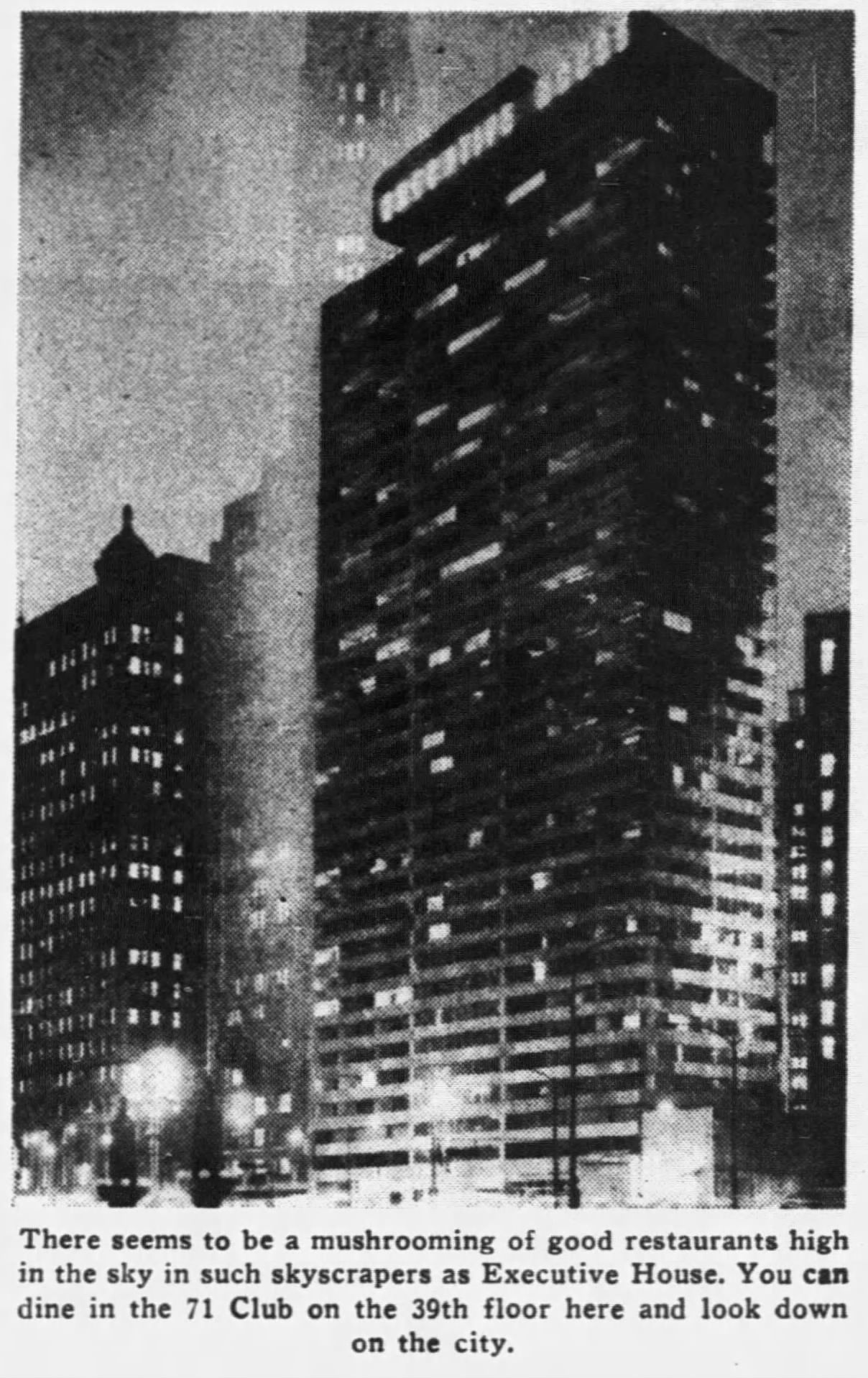

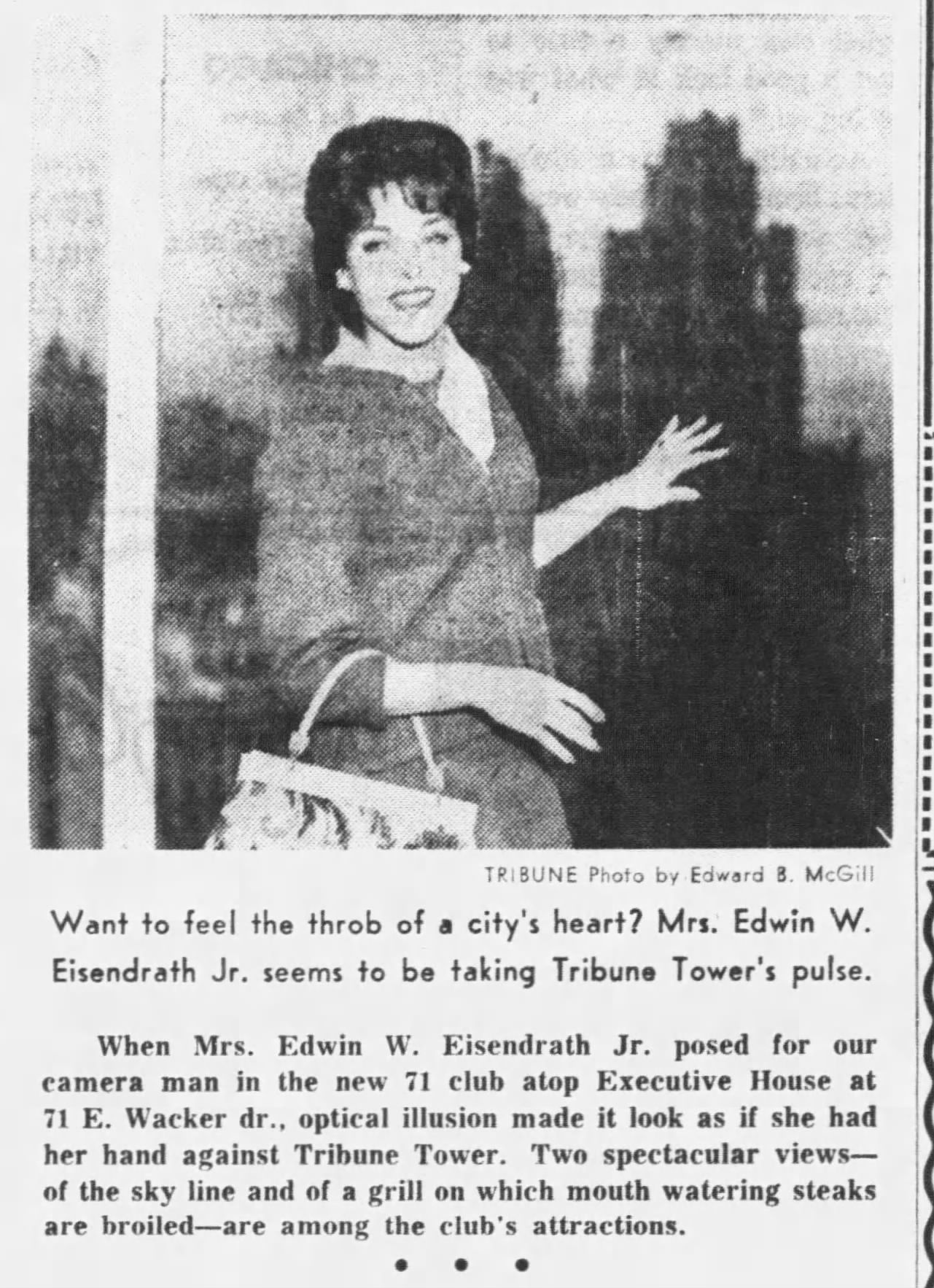

Milton Schwartz wanted to put a helipad on top, but the Daley administration nixed that. Plans for a grandiose penthouse apartment didn’t make sense after the owners pivoted to a hotel model, so the space on top was converted into a club (although it did play a penthouse apartment in a movie–this was Bruce Wayne’s apartment in the Dark Knight).

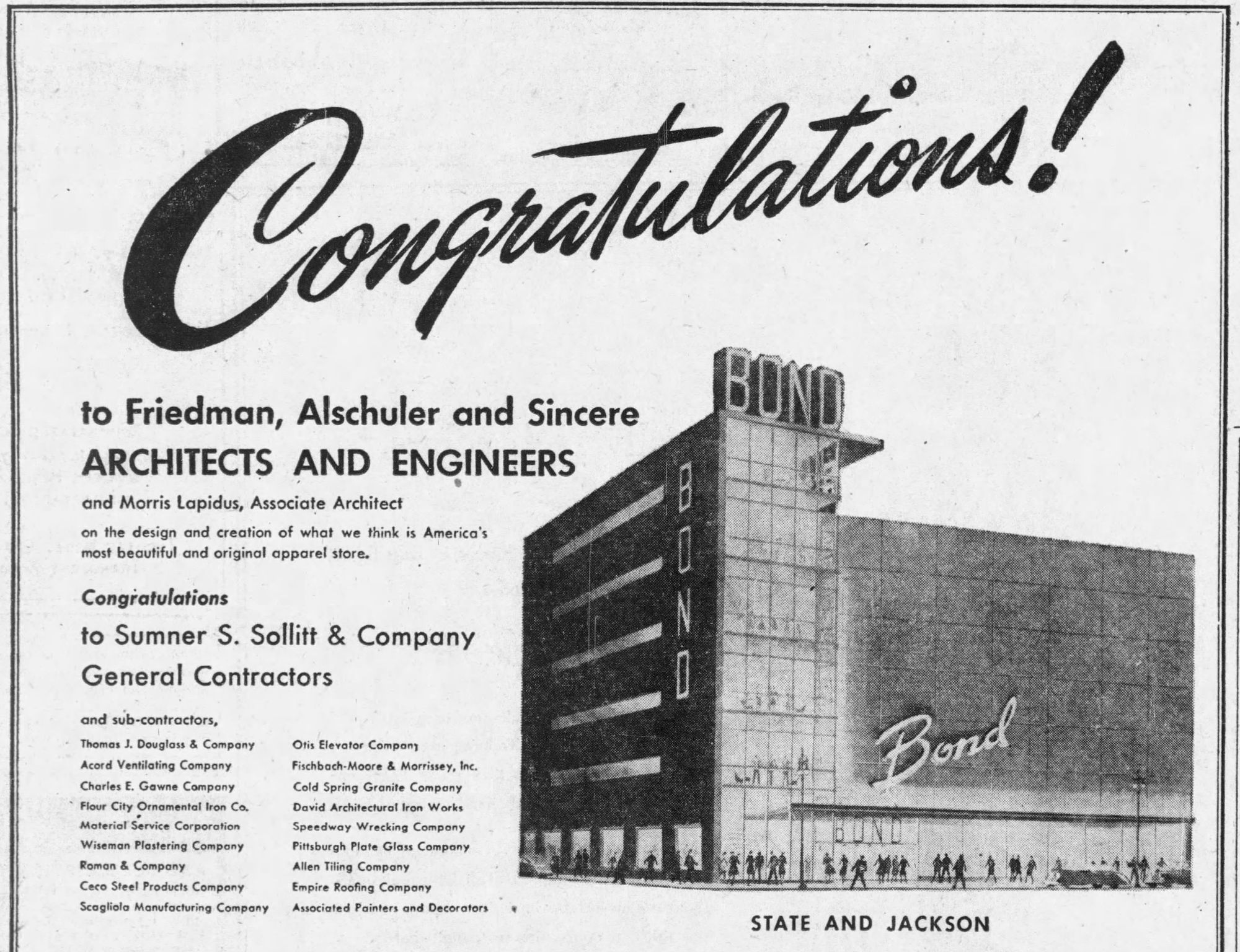

In unexpected twist for me, Morris Lapidus, the antithesis of a Chicago architect, designed the interiors. The man who defined Miami Modernism with a design philosophy of “more is more” and “form follows feeling”, this was one of only three projects Lapidus worked on in Chicago (none of which survive).

The Executive House units were mostly studios with a small kitchenette plus a smattering of one bedrooms. Monthly rent in the cheapest studios was $175 in 1959, equivalent to $1850 today (while less than a new studio would rent for in downtown Chicago today, it doesn’t seem like that much less).

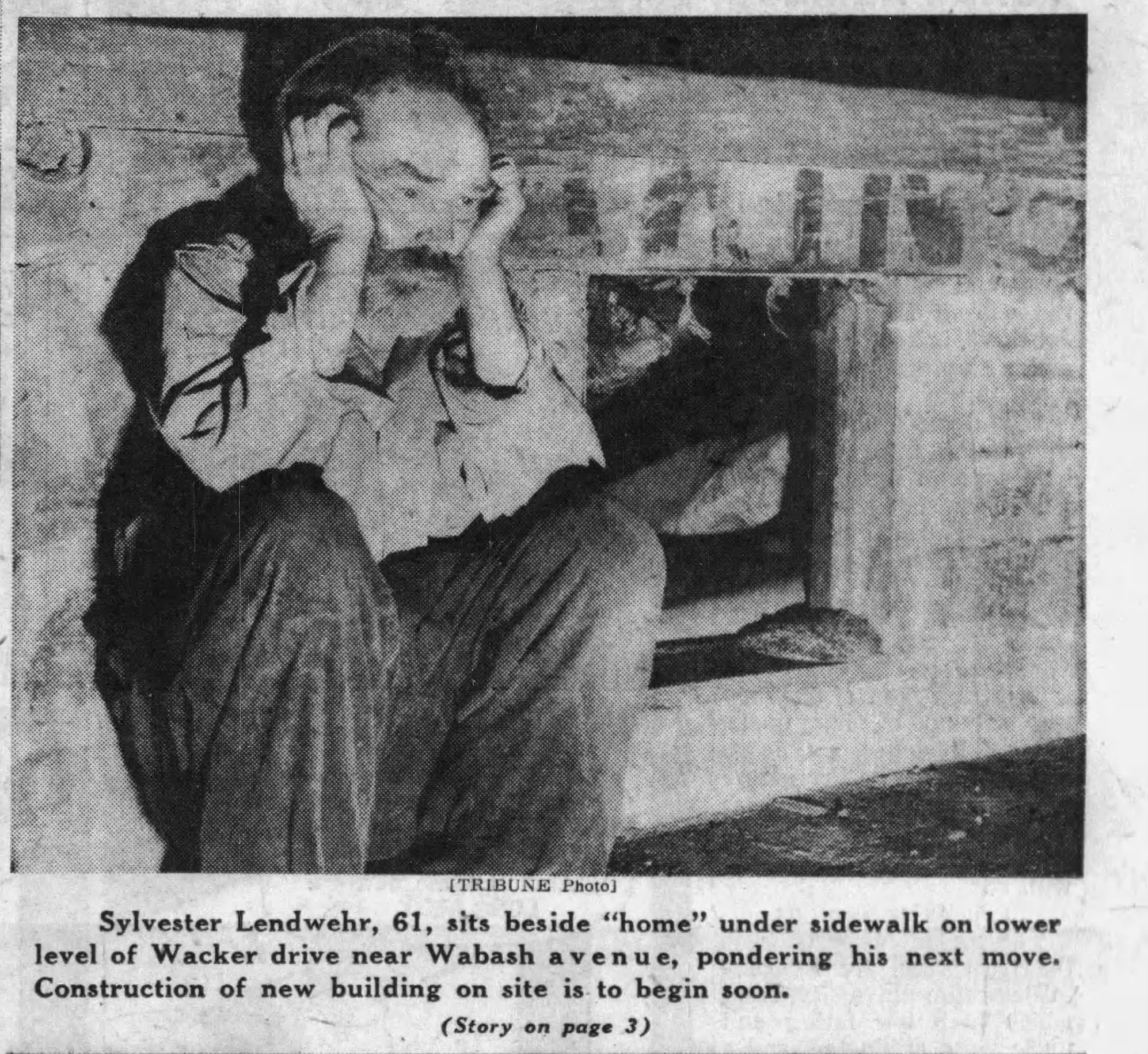

It was also a surprise to me that residential hotels had legs longer than I realized. Despite the stigma, regulatory pressures, and changing lifestyles, it was still possible to build a (very upscale, only partially residential) apartment hotel in the late 1950s. I was curious whether people actually did make the Executive House their permanent residence, and it turns out that they did, at least through the 1960s.

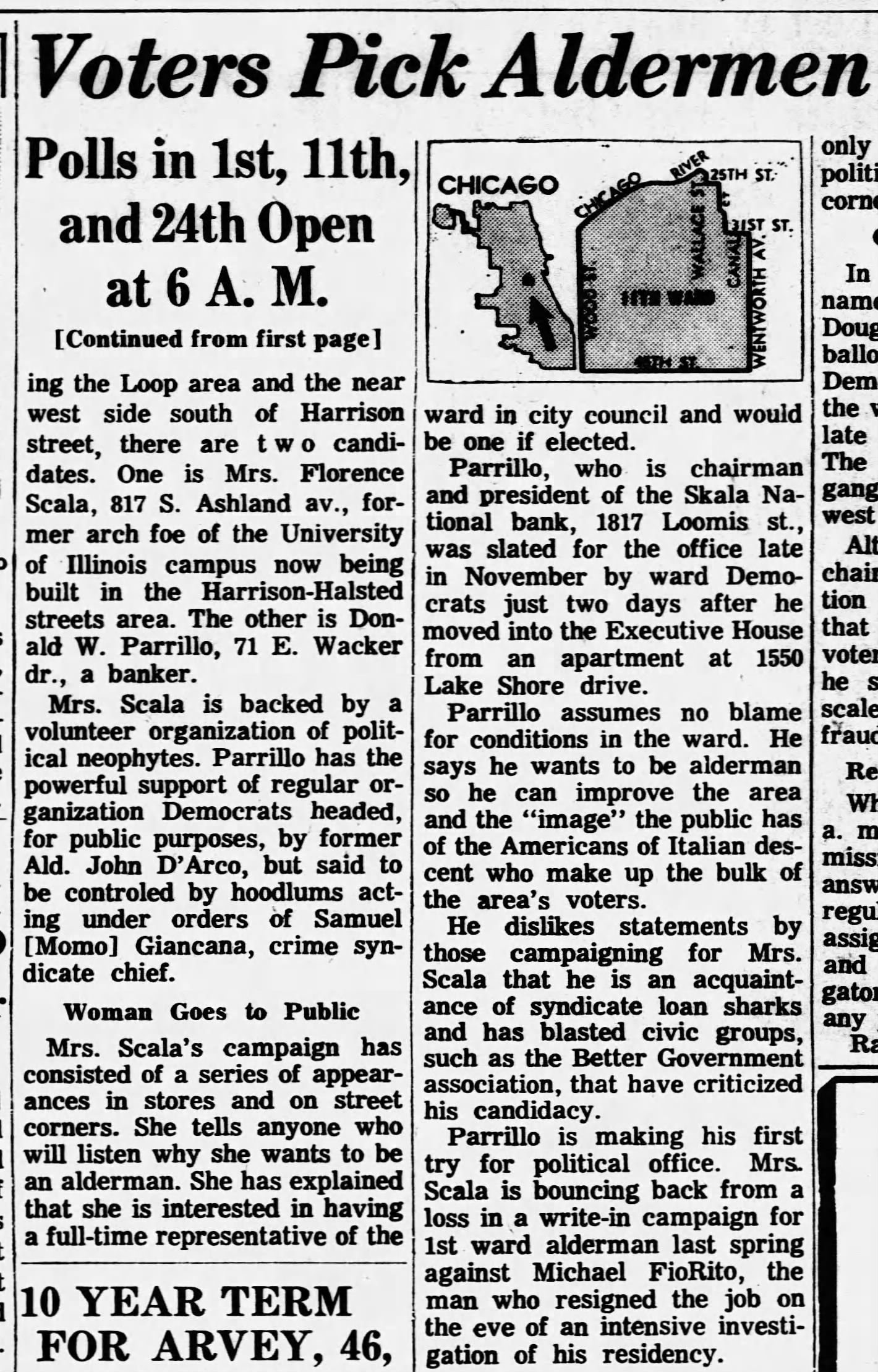

In one very Chicago case of someone permanently residing in the building, in 1964 a machine and mafia-affiliated aldermanic candidate, Donald Parrillo, moved into the Executive House to establish residency in the 1st Ward. Underlining that the fix was in, only two days after moving in the Democratic organization endorsed him. Opposing Parrillo in the 1964 election was Florence Scala, a Daley foe who unsuccessfully fought the city to save Little Italy and her home from being bulldozed for the UIC campus. Scala and her quixotic band of supporters lost here too, roughly 72% - 28%, but given the strength of the Chicago Machine at this point, 3500 votes was considered a victory.

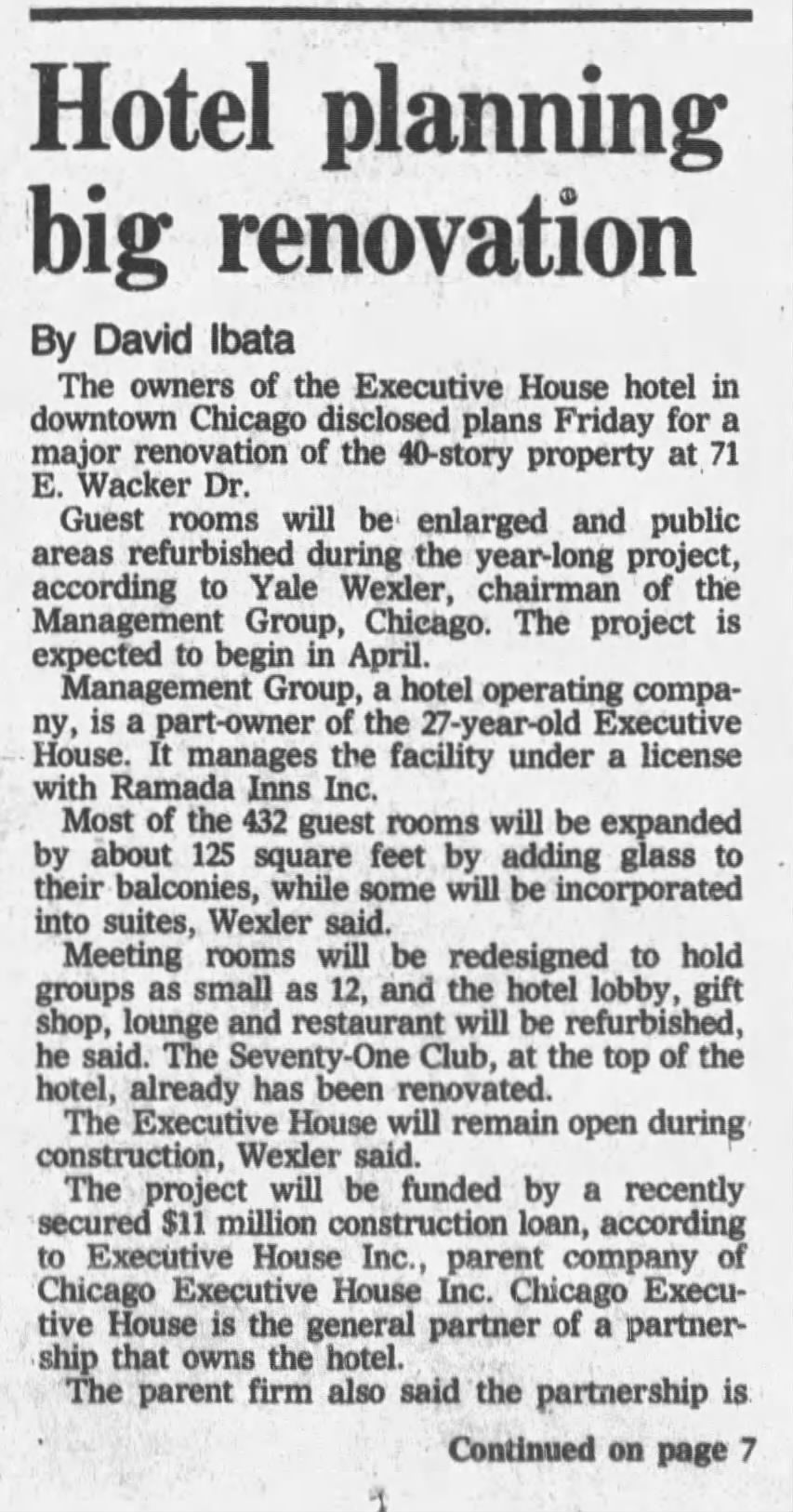

Executive House as a chain went bankrupt in the early 1970s. The owners here sold out in the 1980s, and the hotel became affiliated with Ramada. In 1986, a major renovation added the dark blue glass around the balconies and combined some units into suites. Since the early 1990s the hotel has averaged a new name and brand once a decade or so: renamed the Executive Plaza and was affiliated with Clarion in 1992, rebranded as Hotel 71 in 2002, then the Wyndham Grand in 2012. Since 2019, the hotel has operated as the Royal Sonesta–still fresh 65 years later.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Thomas Leslie had a good write up in his Architecture Farm blog

- Milton Schwartz in the Chicago Architects Oral History Project–there's quite a lot on the Executive House

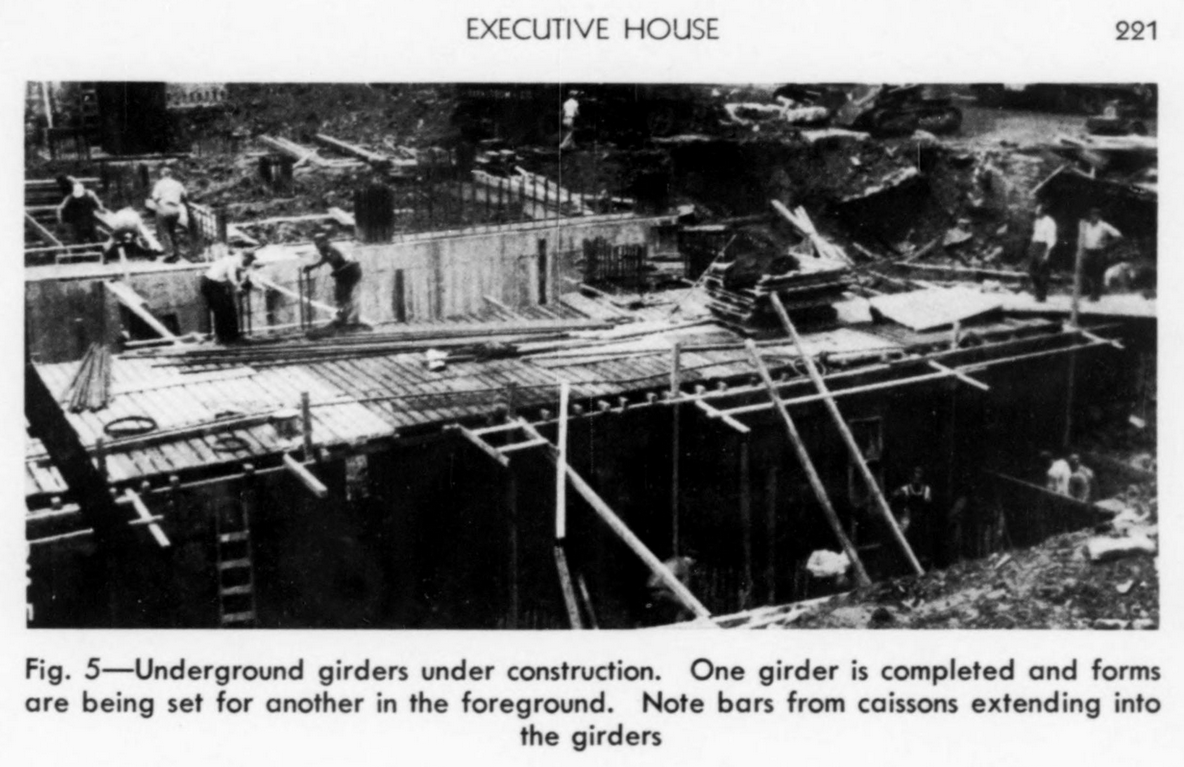

- Engineer Henry Miller writing about the building in 1959 in the Journal of the American Concrete Institute

- An article on the builing in Architectural Record in 1959

- A great WBEZ read on Florence Scala and the fight to save Little Italy from Mayor Daley

Member discussion: