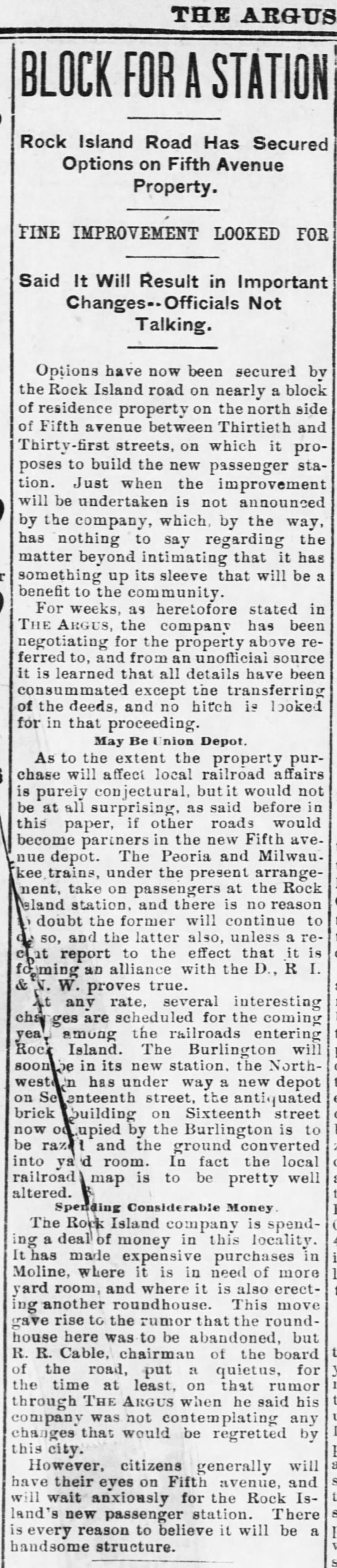

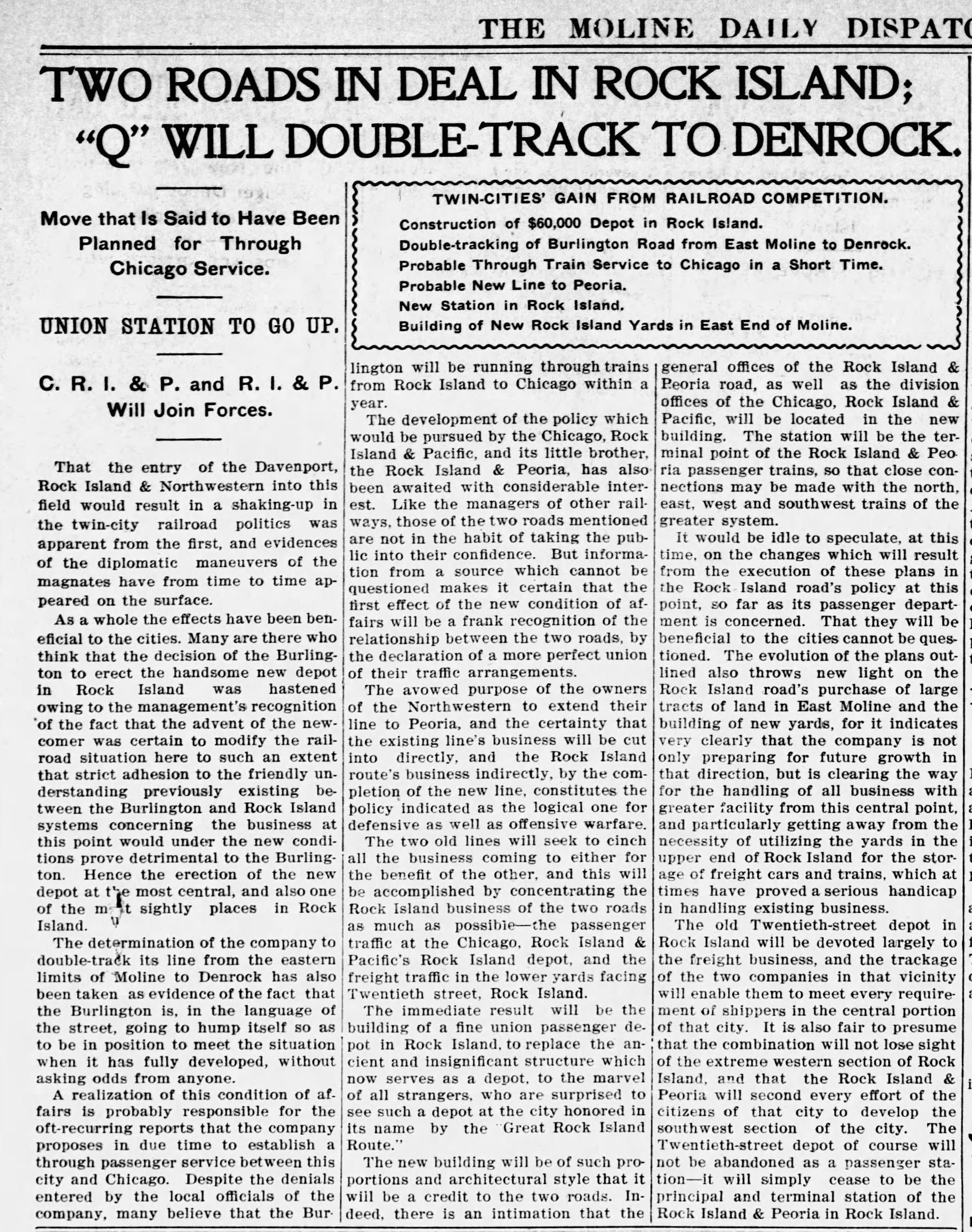

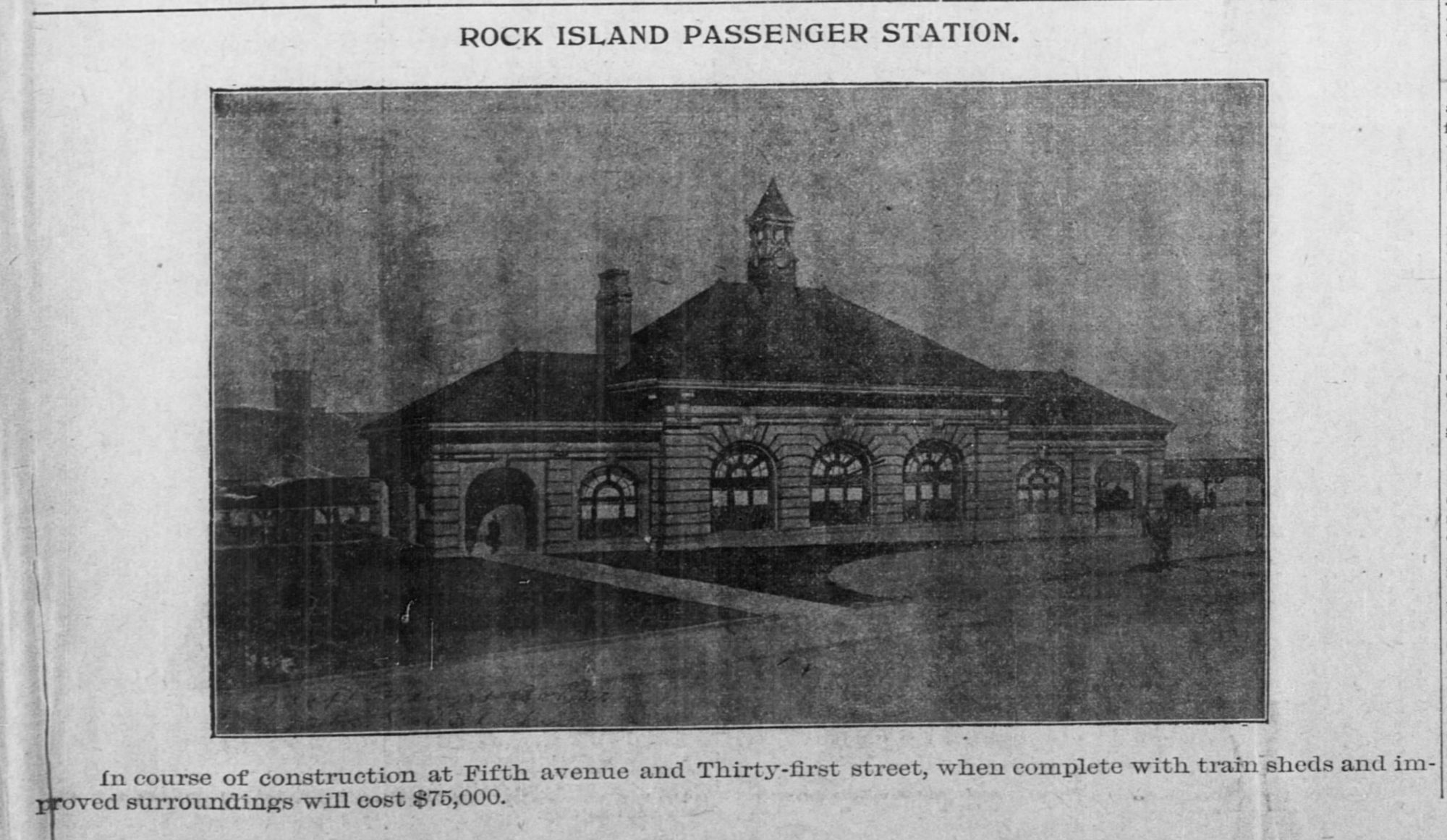

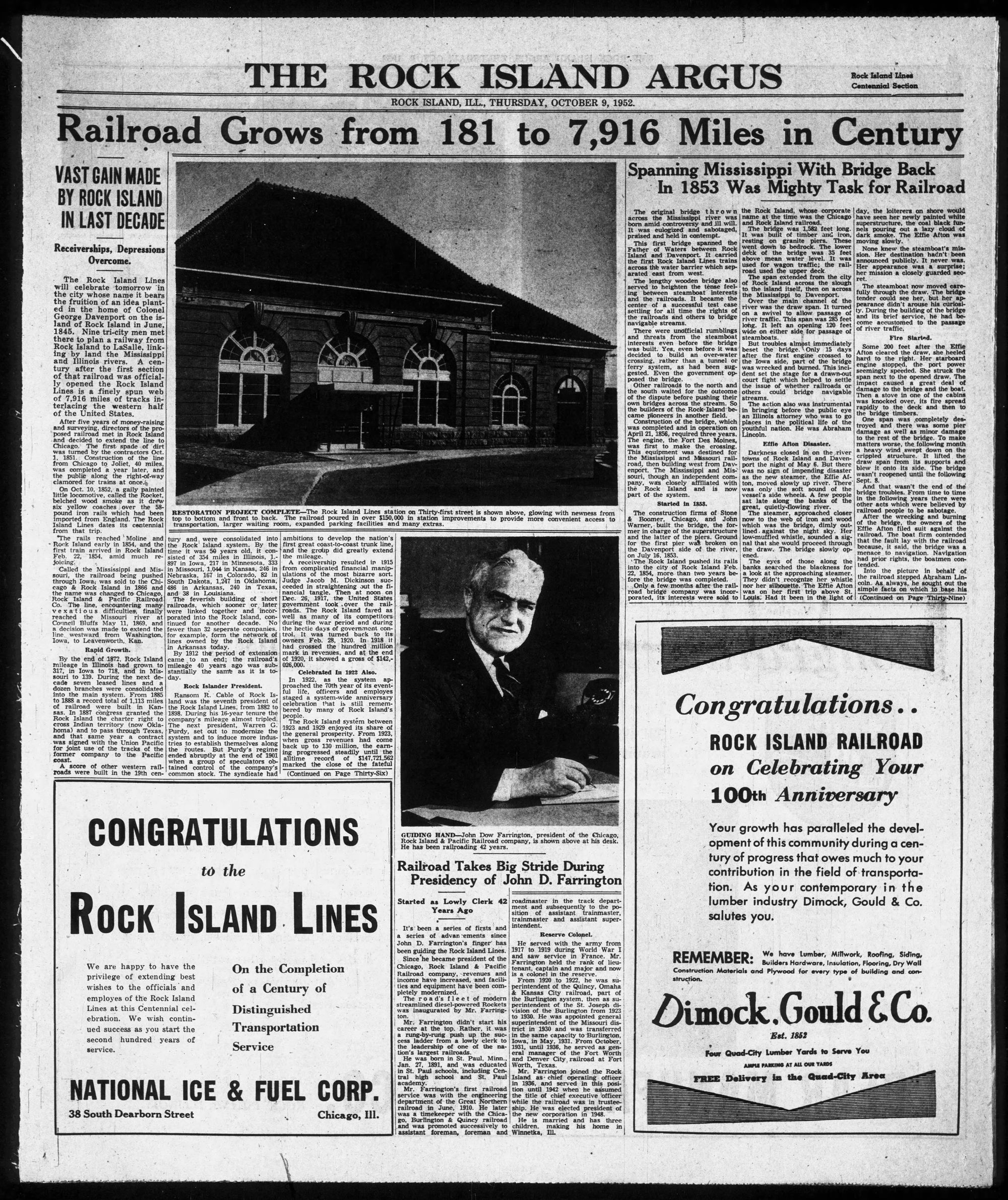

The Rock Island Line may have been a “mighty good road”, but the Chicago, Rock Island, & Pacific passenger station in its namesake city is surprisingly humble. Built in 1902 and designed by Frost & Granger out of Chicago, this was the CRI&P’s third (and final) passenger depot in Rock Island. Immortalized in a famous folk song written by African-American CRI&P workers in Arkansas, which was covered by Lead Belly, Johnny Cash, and Pete Seeger amongst others, the Rock Island was one of the greatest of the granger railroads that hauled the Upper Midwest’s harvests to market in Chicago–which explains the modesty of the depot here: freight was king.

I think in hindsight you can pretty convincingly argue that by the time this station was built, the rail importance of the city of Rock Island had already peaked—the relationship between the railroads and agricultural production was already changing, and the whole "first bridge across the Mississippi River" thing was ancient history.

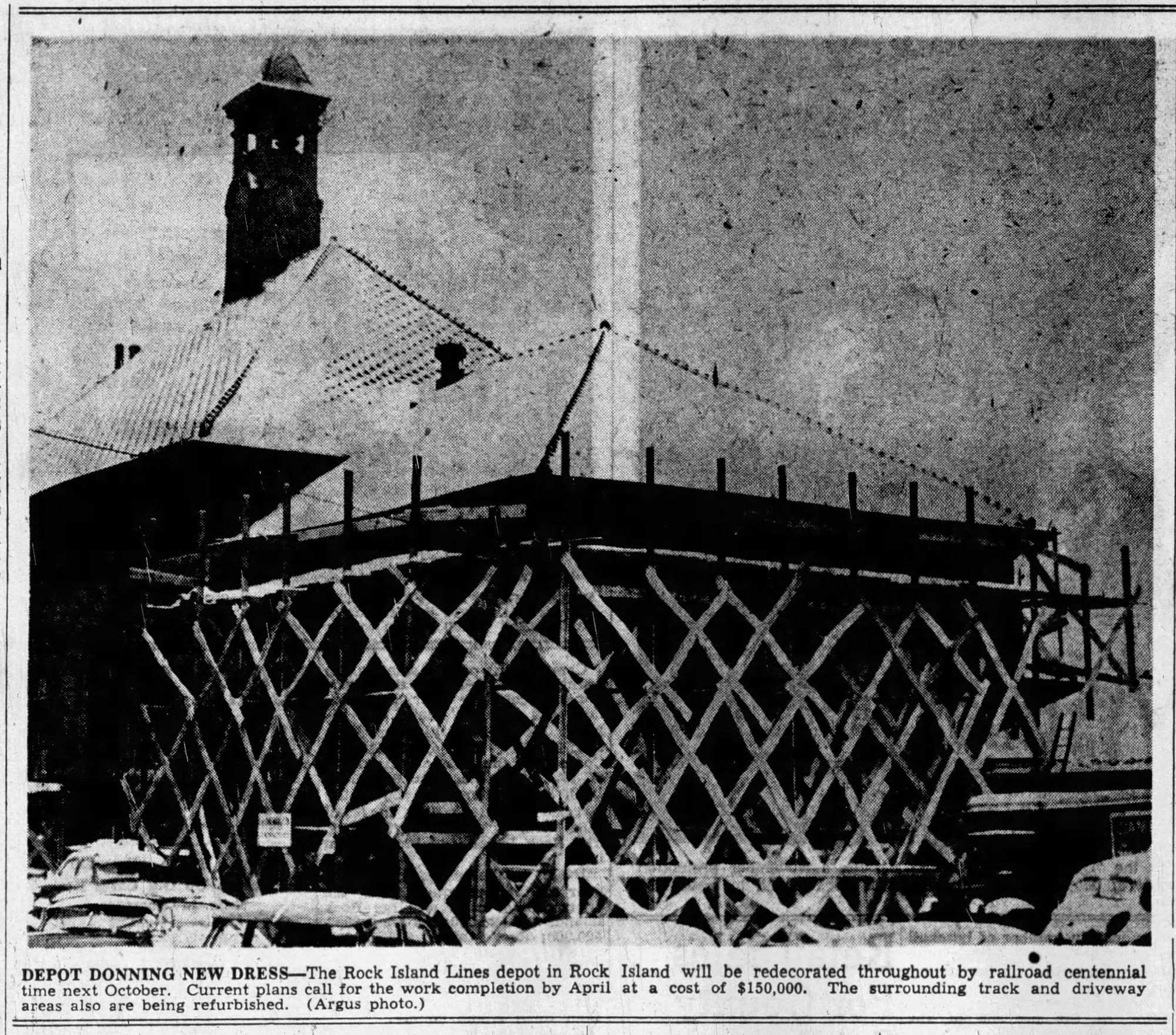

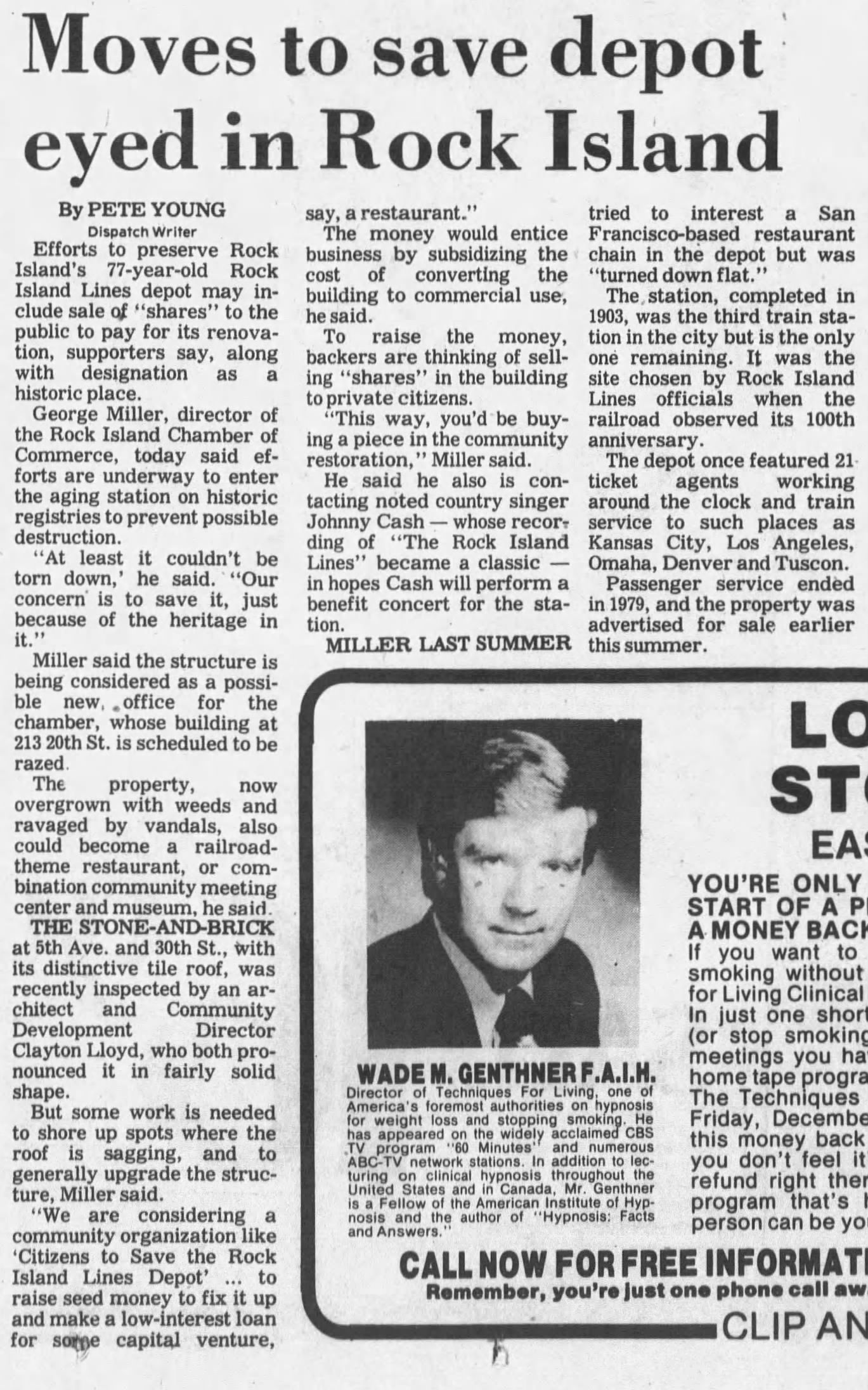

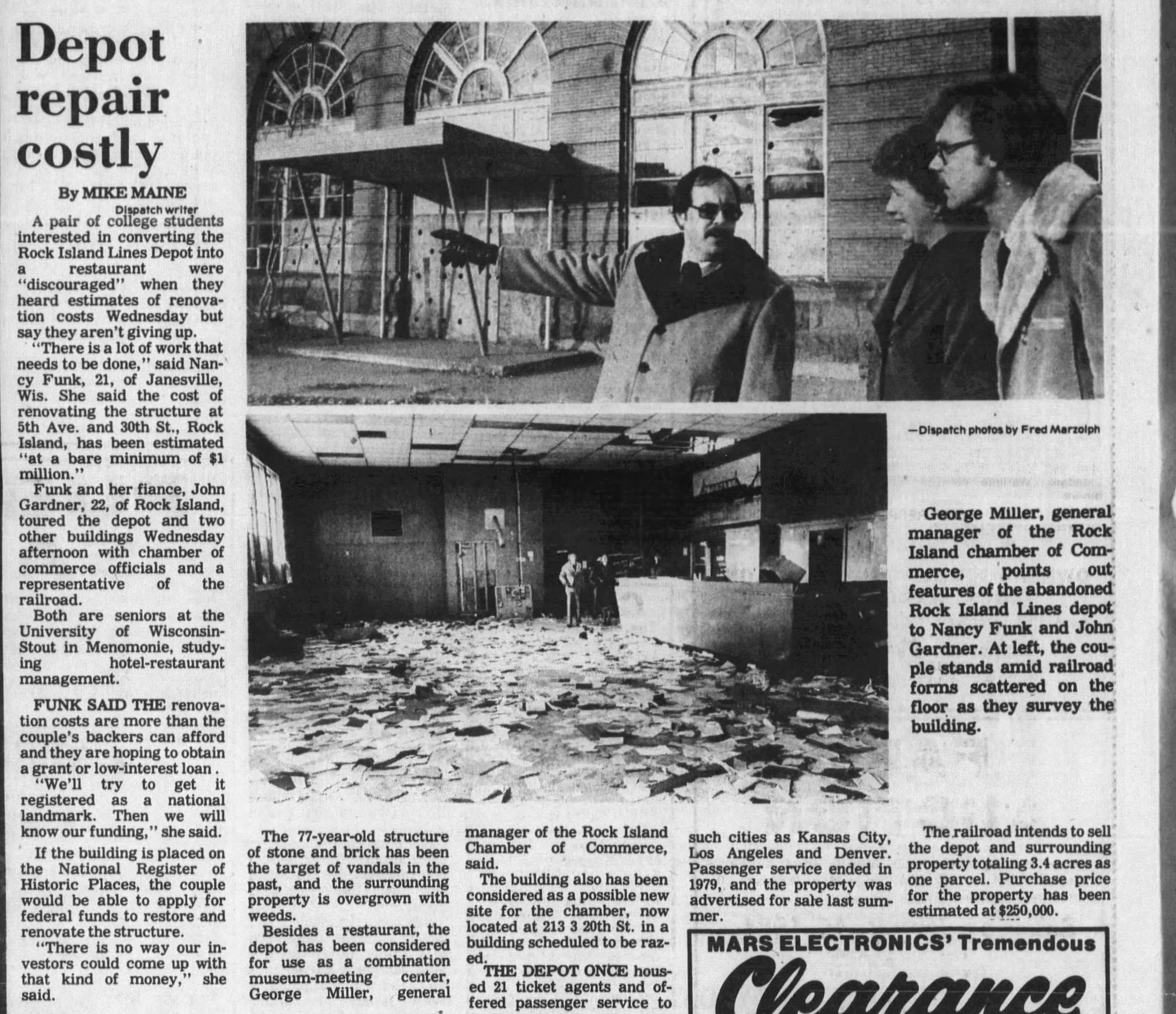

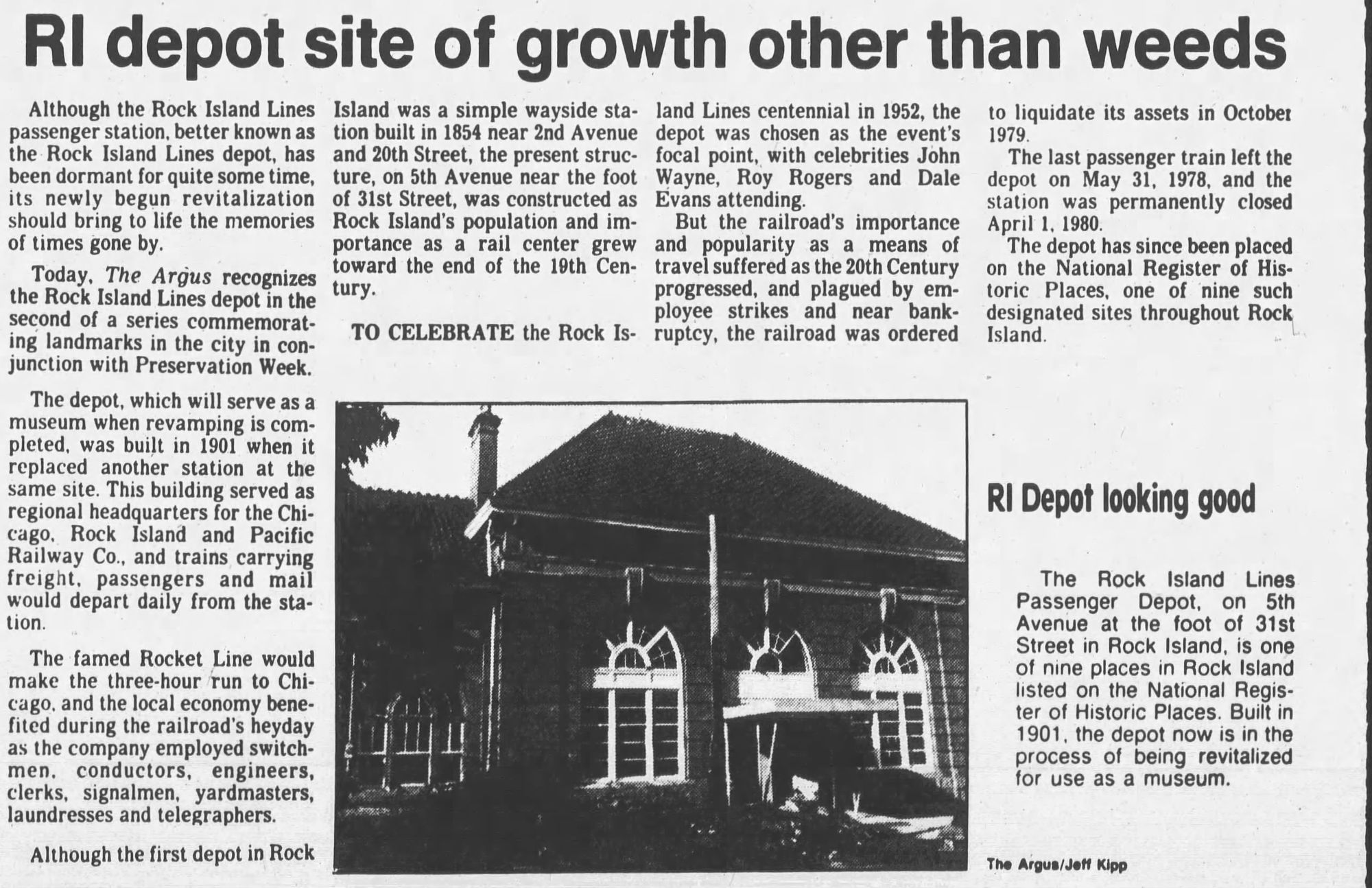

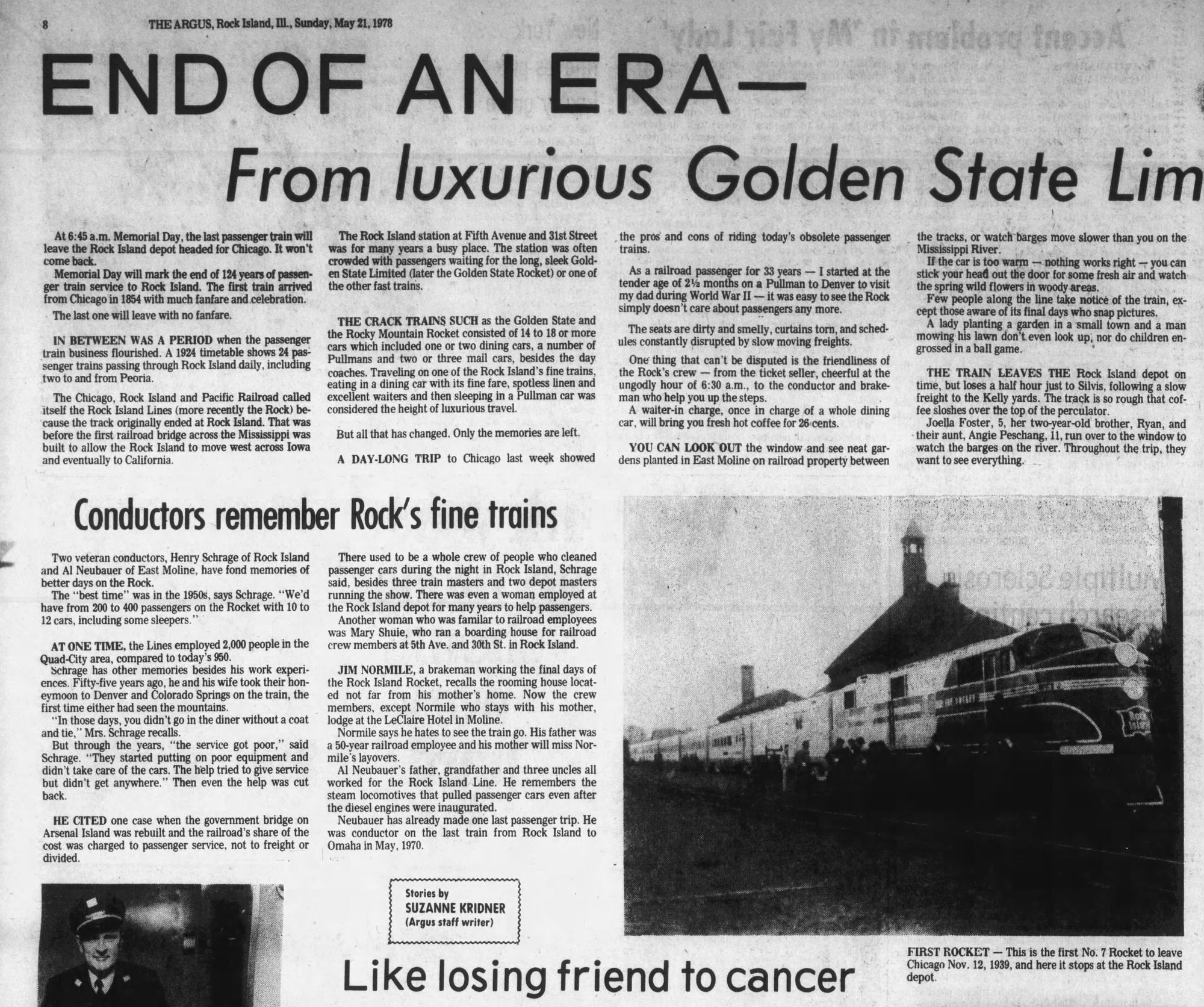

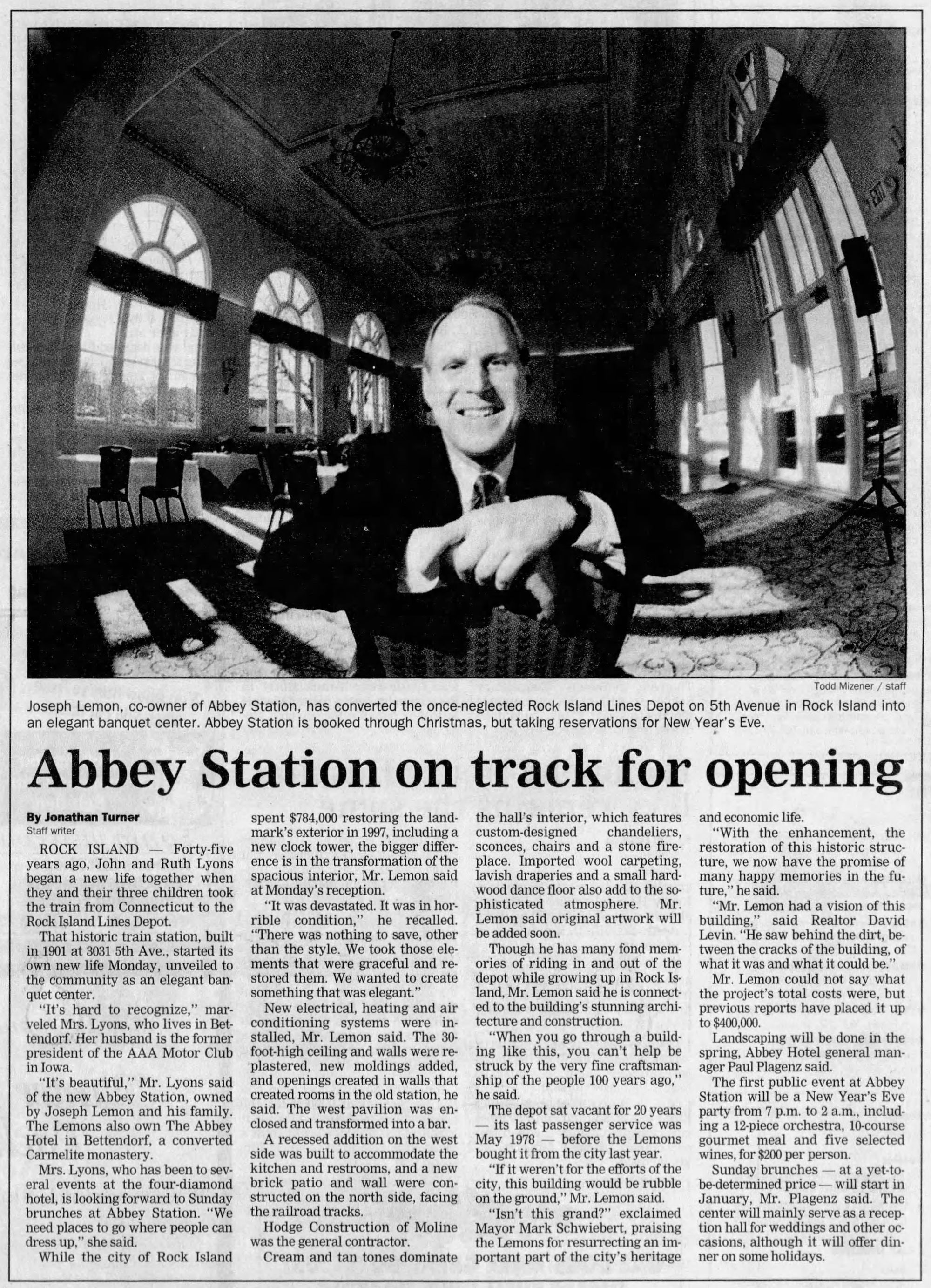

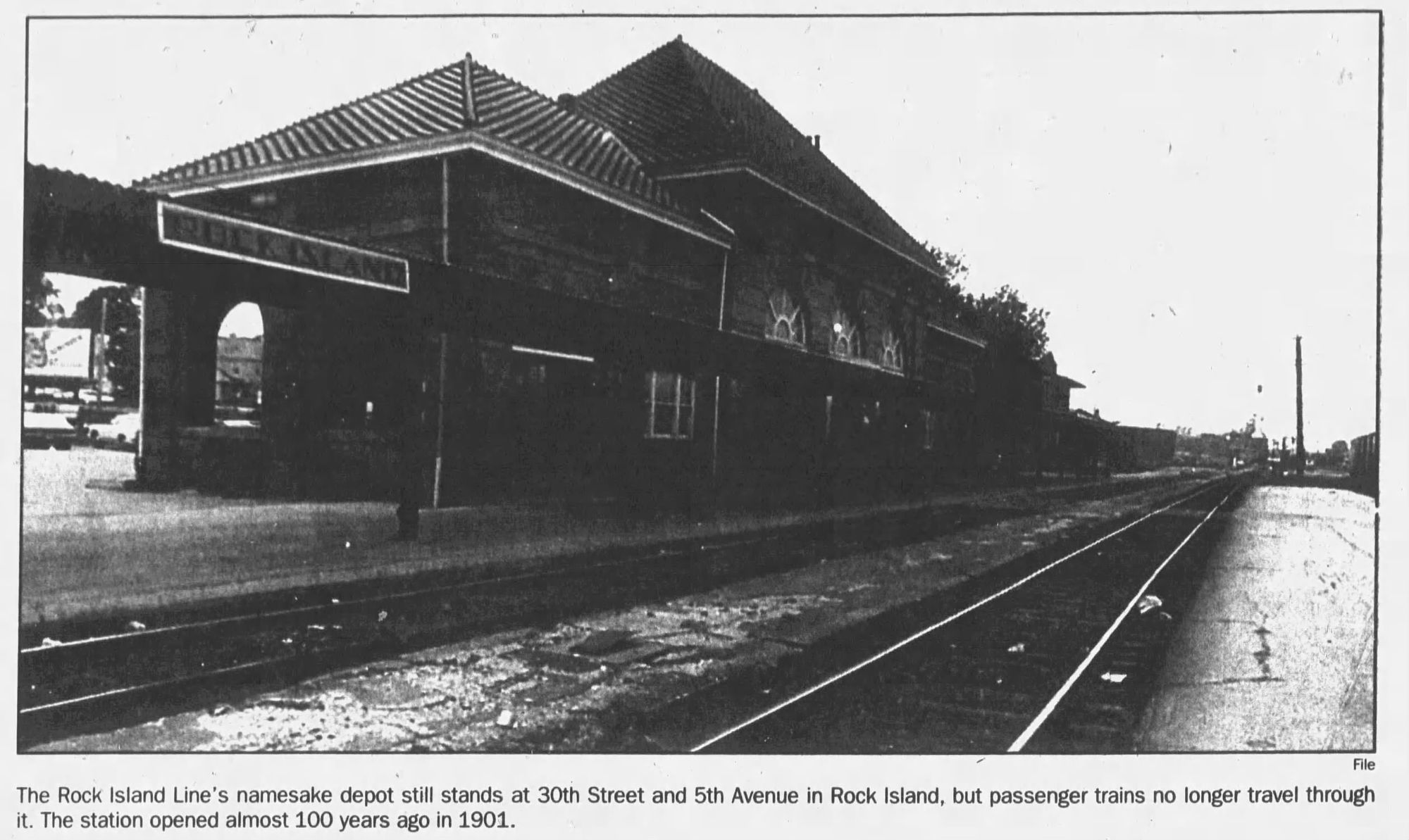

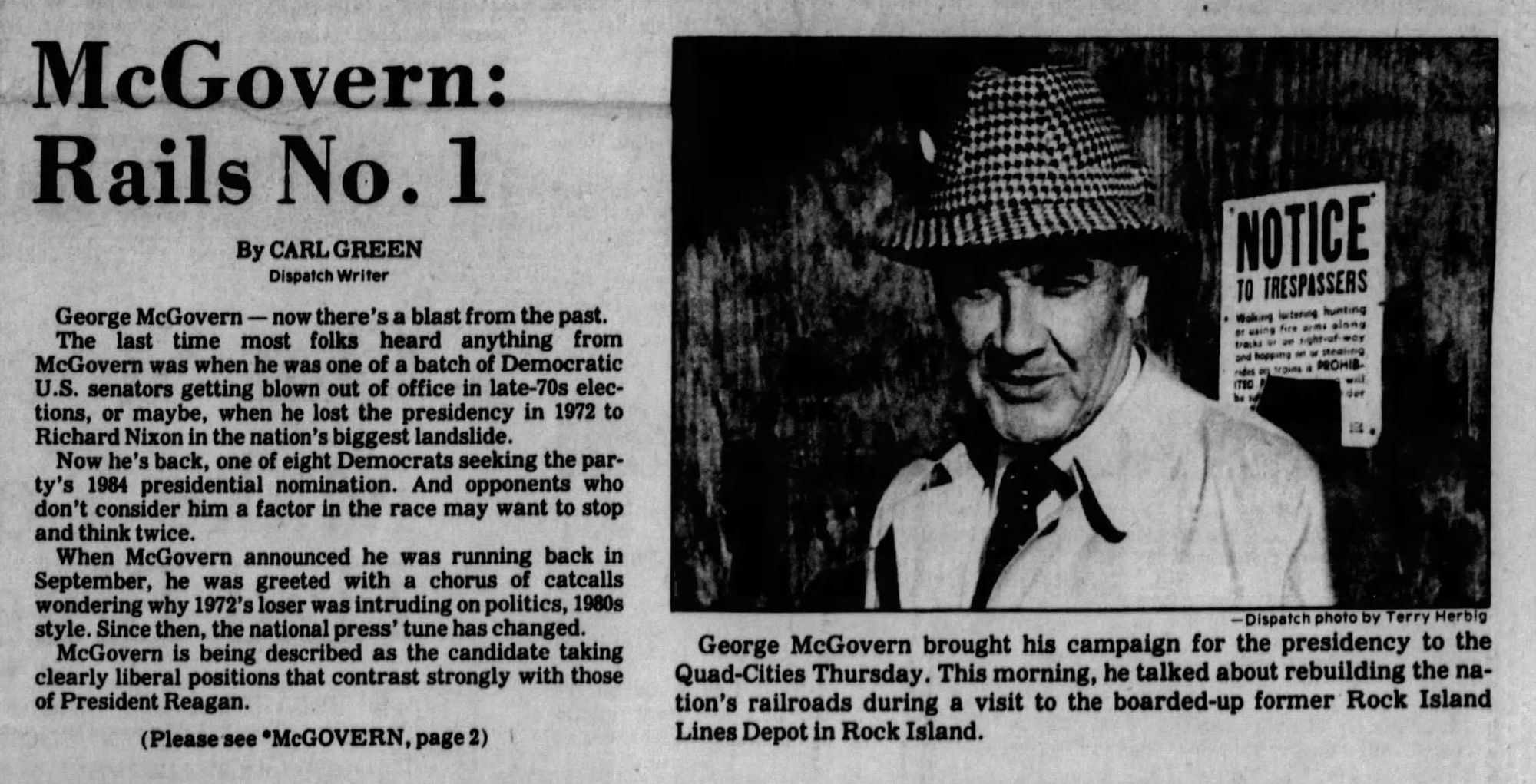

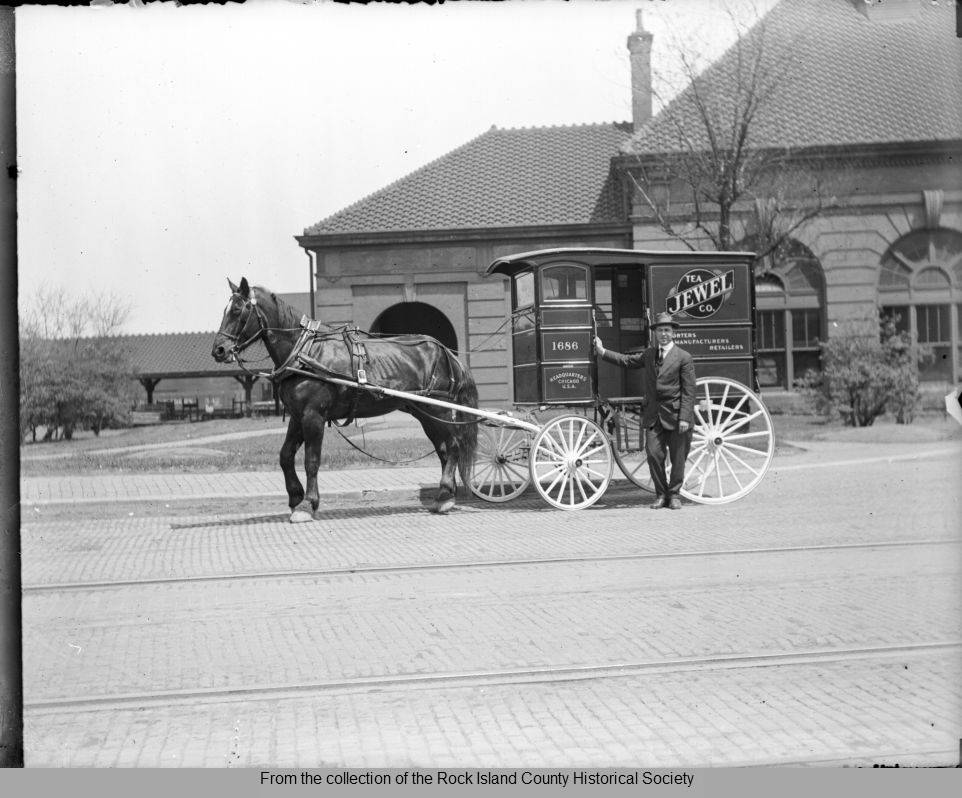

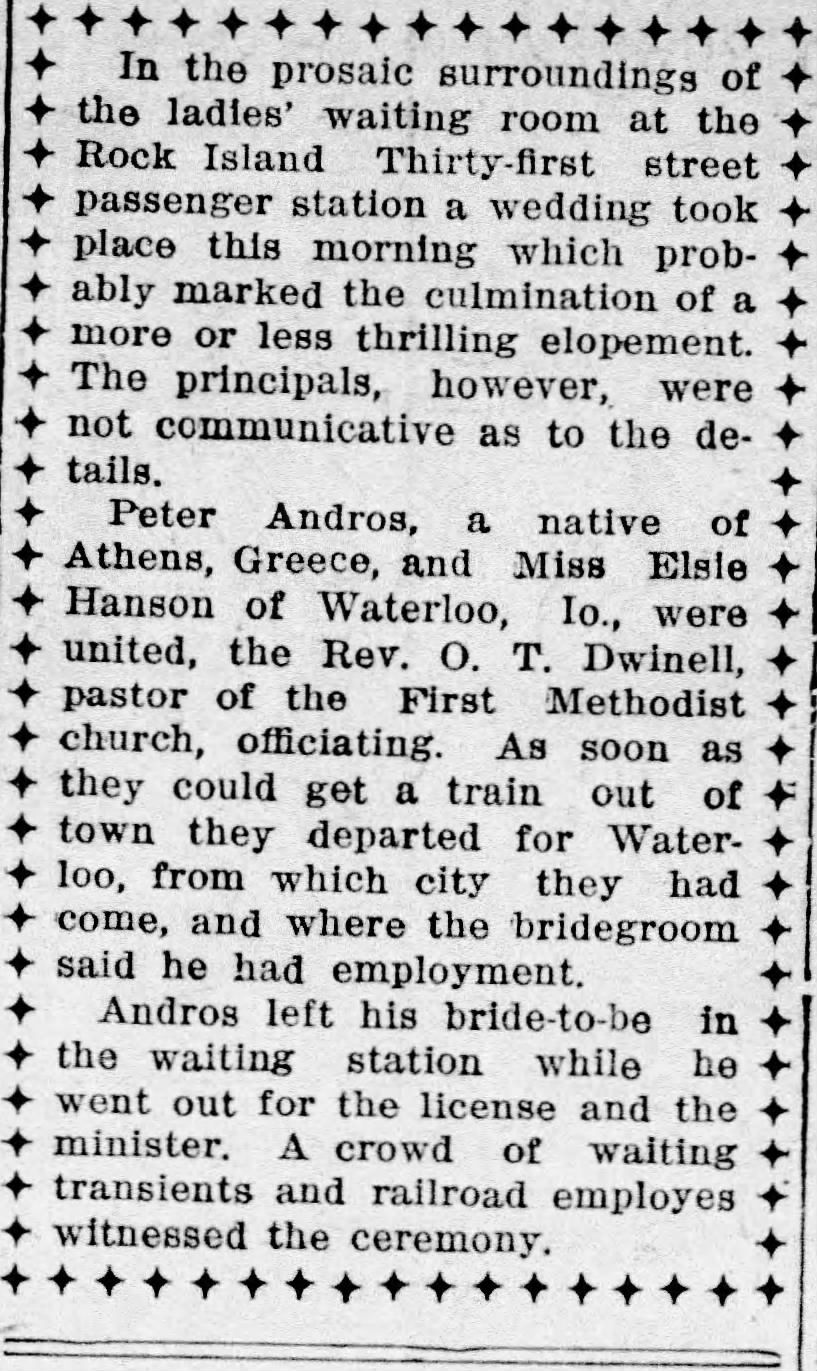

The Rock Island Line, on the other hand, had a boom-and-bust 20th century until it ceased operations in 1979, killed by deferred maintenance, cost-cutting, duplicative routes, and a failed ten year merger saga with Union Pacific. After years of appeals fighting to save the Quad Cities Rocket, the last passenger train left the Rock Island station December 31st, 1978. The dying railroad abandoned the station soon after. The deteriorating station could’ve easily been torn down, but the city government, armed with public funding and federal tax credits, swooped in to save it, before they handed it off to a private operator to complete the restoration. Rechristened as Abbey Station, the old CRI&P depot now serves as a banquet hall–not a bad place for a railfan wedding, I’d say.

The architects here, Frost & Granger, were a funny little partnership. Charles Sumner Frost, who'd previously worked with the venerable Henry Ives Cobb, married Mary Hughitt. Alfred Granger was married to...Belle Hughitt. They were both daughters of Chicago railroad executive Marvin Hughitt. Naturally, the brothers-in-law became the architects of choice for their father-in-law’s company, the Chicago and North Western Railroad. Frost & Granger designed 127 buildings for that railroad, the vast majority of their body of work together—this was part of the small portion of the firm's work outside the Chicago and North Western. When daddy retired from his company in 1910, the sons-in-law dissolved their partnership soon after. It’s a weird but illustrative little example of the kind of petty self-dealing and nepotism used by the wealthy to keep their money in the family—it doesn’t seem like an overstatement to say that the partnership of Frost & Granger existed mainly to extract commissions from the Chicago and North Western Railroad, a vessel for Marvin Hughitt to pass money to his daughters through architecture, with anything else (like this) was a bonus. After the partnership dissolved, Frost would go on to design Chicago's Navy Pier, amongst others (he seems like the more accomplished son-in-law).

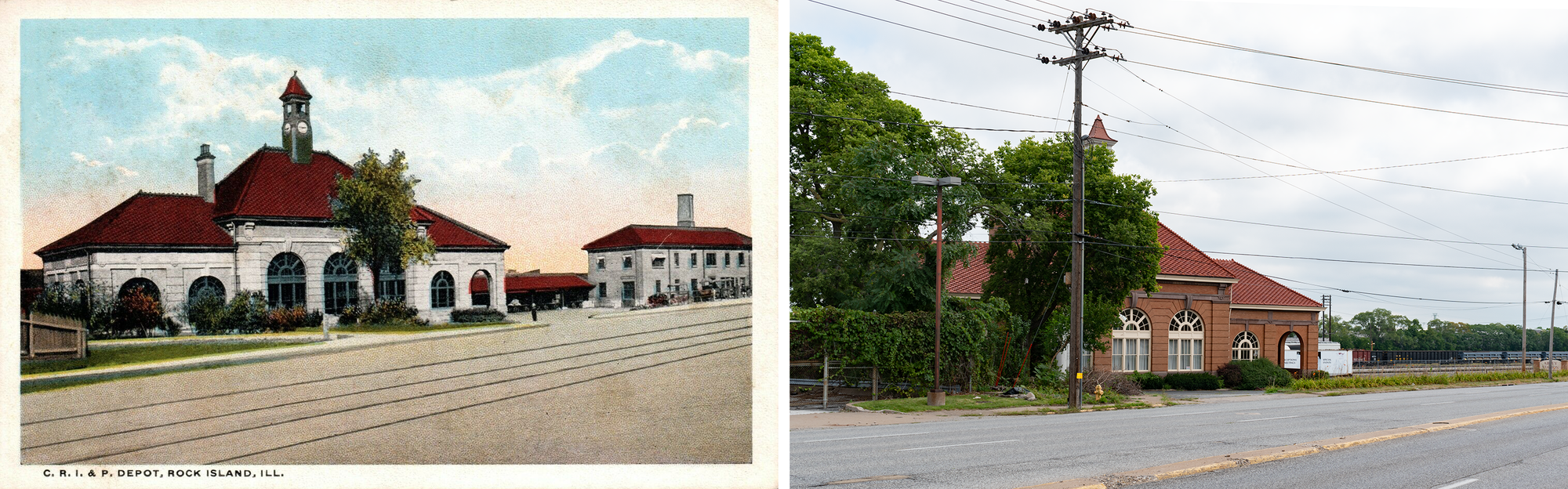

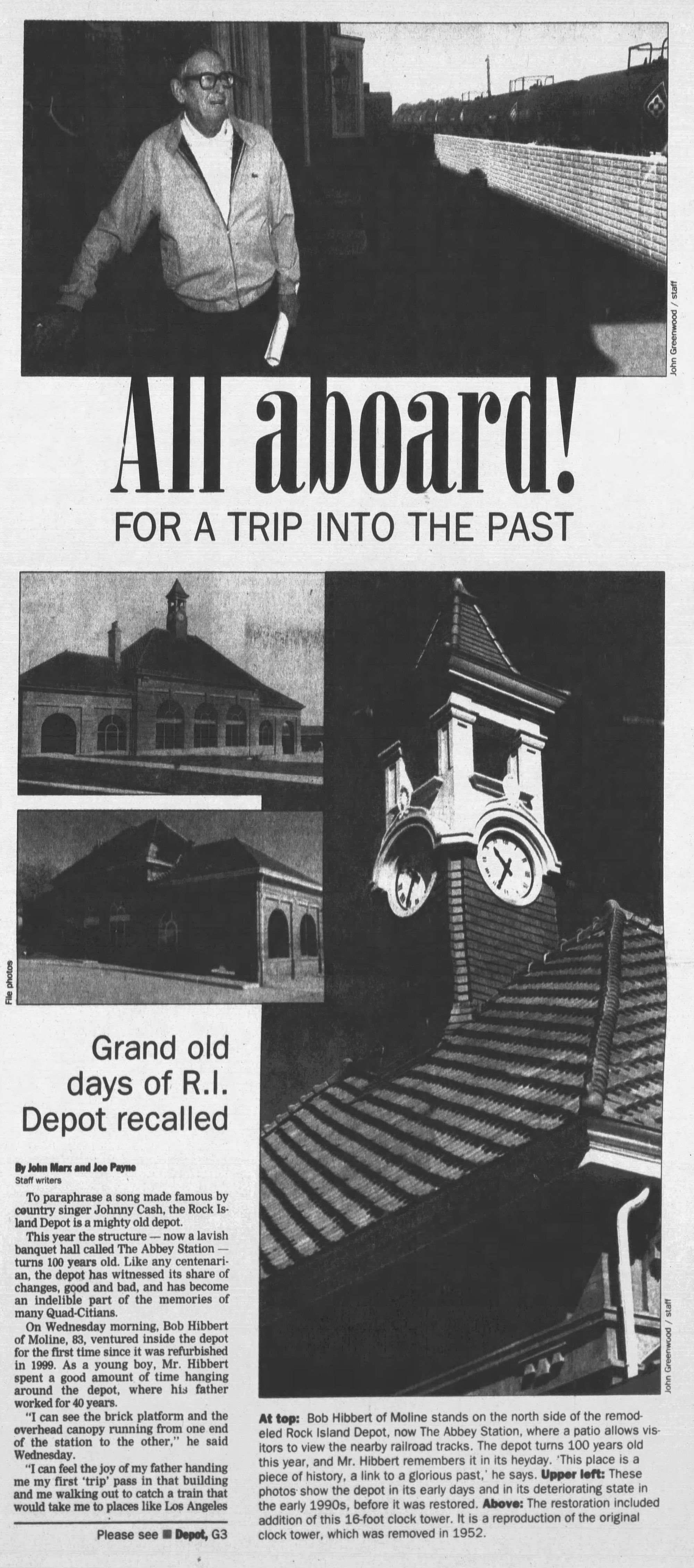

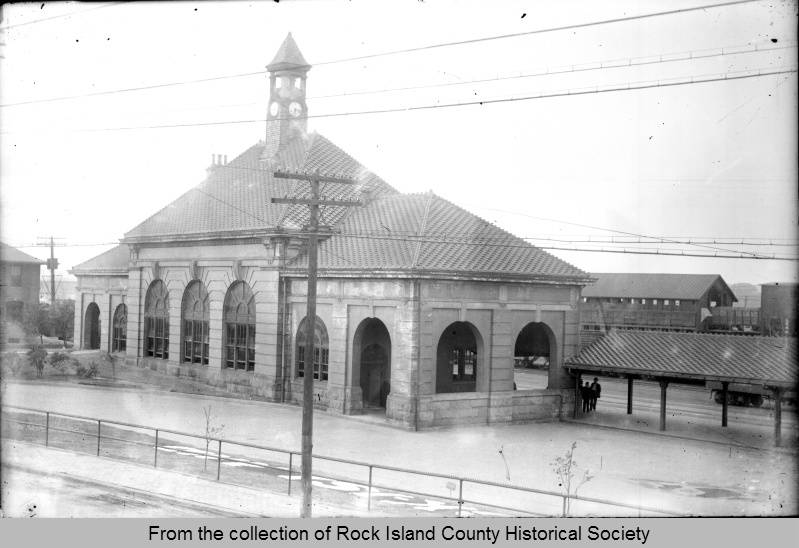

There’s one major difference between the postcard and the present-day photo–the baggage and express building on the right has been demolished. This was actually a four building complex when it was built in the early 1900s, with the passenger station accompanied by a laundry building and a commissary, as well as the baggage and express building. However, the other three were left out of the NRHP listing, and the laundry and commissary buildings were demolished pretty quickly after the Rock’s bankruptcy.

The baggage and express building, which housed office space, lacked “architectural distinction, visual appeal, sentimental attachment, and historical significance”, according to (pretty funny) contemporary accounts. It survived into the 1990s, but was then torn down to provide building materials for the restoration of the depot itself.

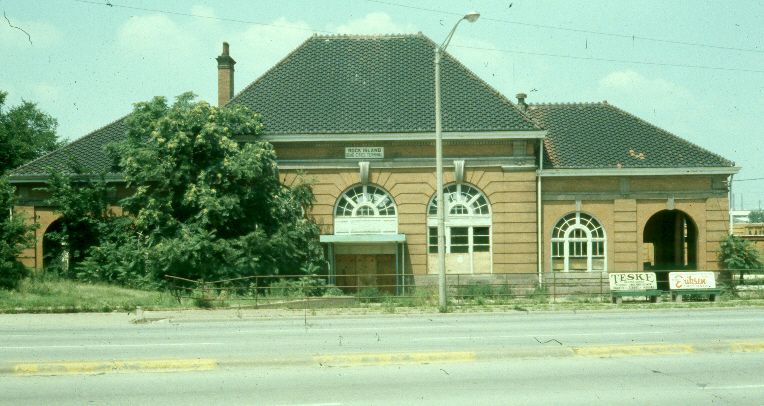

A more subtle change is the clocktower. It’s not the original, which was removed during renovations that gussied up the station for the CRI&P’s bicentennial in 1952. A reproduction was re-installed in 1996 during the city’s renovations of the exterior.

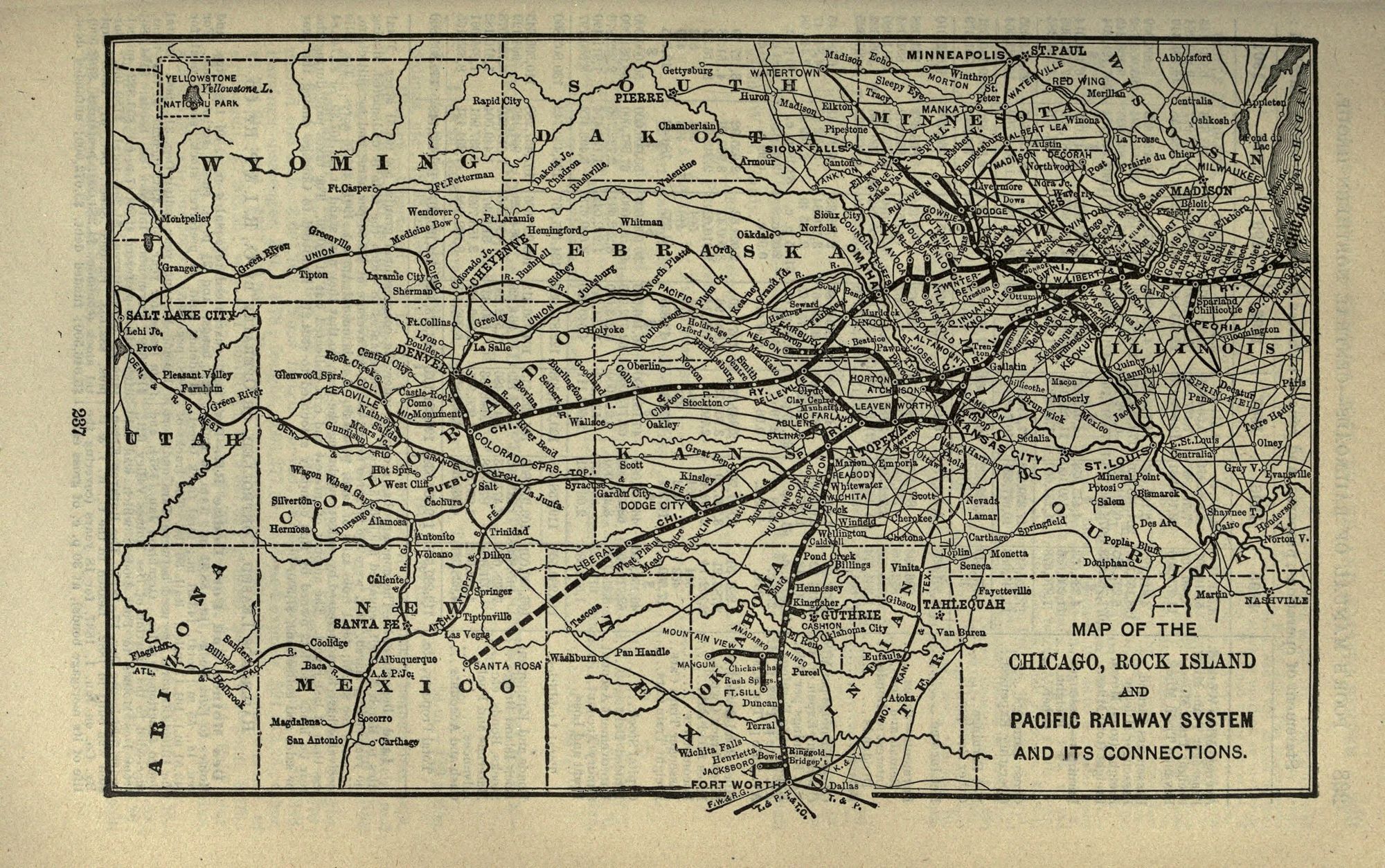

How did an obscure little Illinois city end up lending its name to one of the most important railroads in US history? Access to the agricultural hinterland, its location on the Mississipp0i River, and...luck/happenstance. The Chicago, Rock Island, & Pacific’s predecessor railroad planned on terminating at LaSalle, in central Illinois, but someone made the bright call to connect it all the way to a growing boomtown on the lake–Chicago. The first Chicago & Rock Island (...the Pacific part would come later) trains rolled into Rock Island in 1854. Two years later the railroad was the first to bridge the Mississippi River (a collision between a steamboat and the bridge led to a famous court case argued by…Abraham Lincoln!).

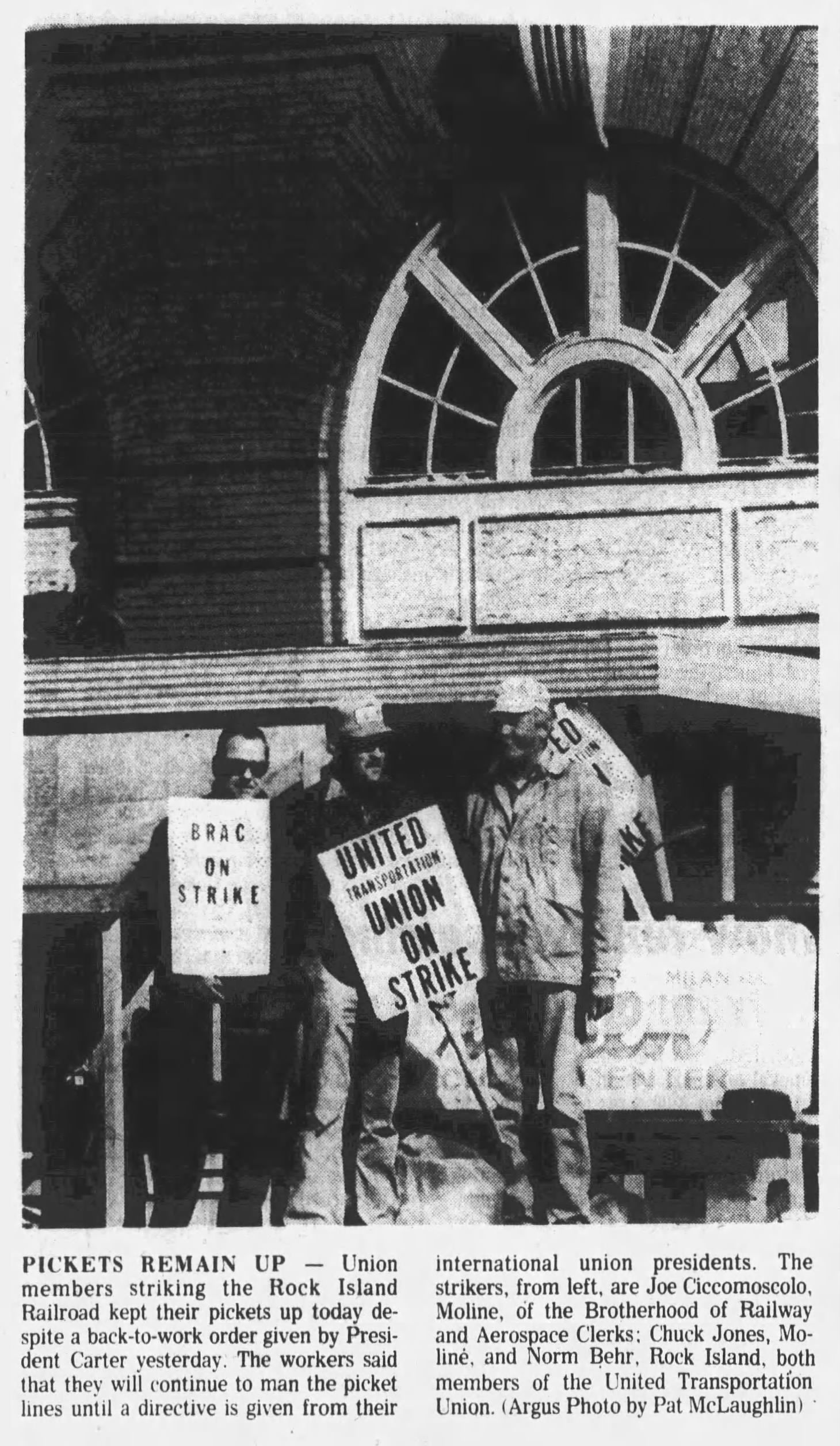

Incredibly influential in the westward expansion of rail and with agriculture its lifeblood, CRI&P track crisscrossed the Upper Midwest. However, the railroad never really diversified away from agriculture–so when agricultural traffic dwindled in the 1960s, the Rock Island Line had a big problem. Union Pacific proposed a merger in 1964, but the antitrust considerations were so large, and competing railroads so opposed, that it took the Interstate Commerce Commission 10 years to make a decision. In the meantime, the Rock Island cut costs, letting rolling stock and rail infrastructure deteriorate, waiting for the merger that never ended up closing. In the mid-1970s, no one left to merge with, left out of Amtrak, bedeviled by slow orders, and fighting with its labor unions, the railroad finally failed in 1979. Turns out the railroad was actually a decent business under all the debt and deferred maintenance–almost all the CRI&P’s major routes were picked up by competitors during the bankruptcy proceedings and are still in use. The liquidation of the railroad actually raised so much money that even after paying out all the creditors, the leftover company had enough capital to enter the...vacuum business? Renamed the Chicago Pacific Corporation, they bought Hoover.

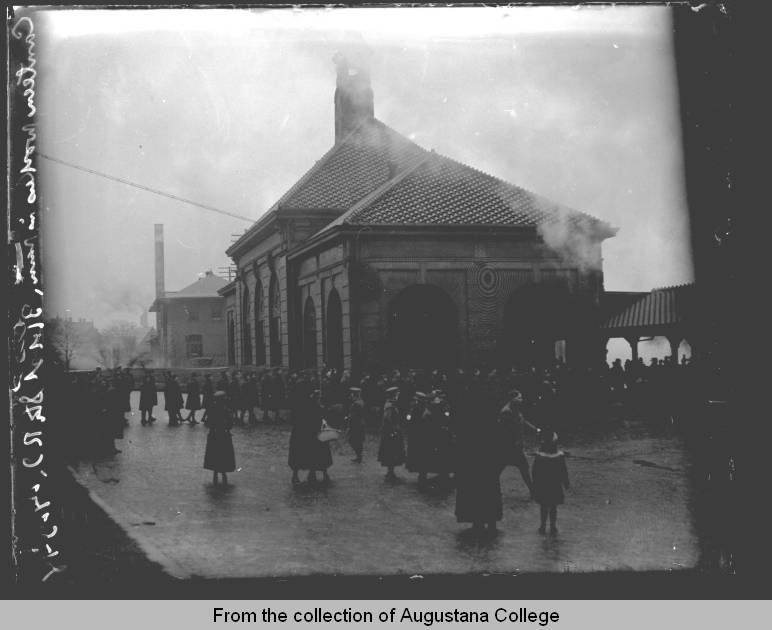

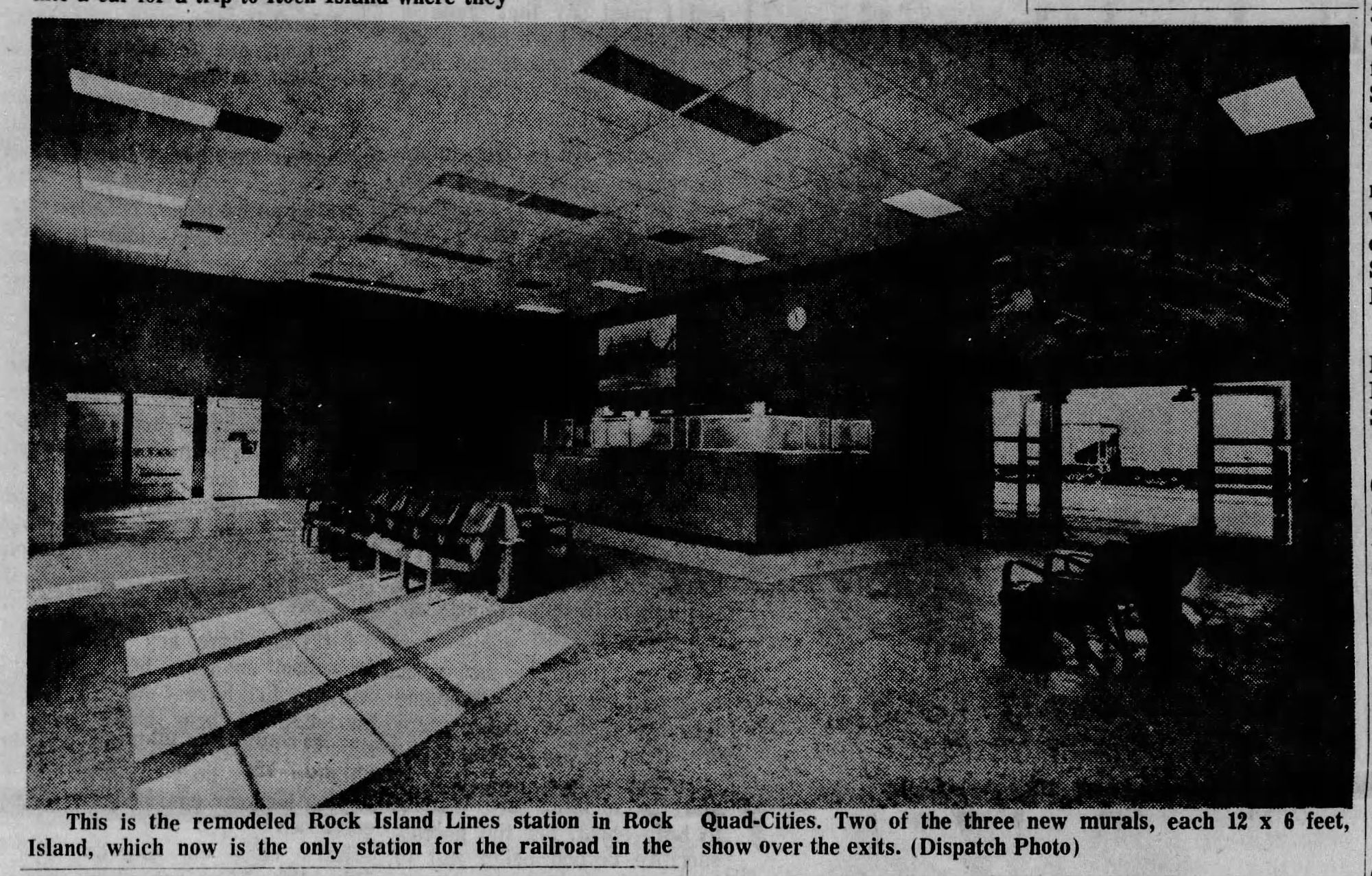

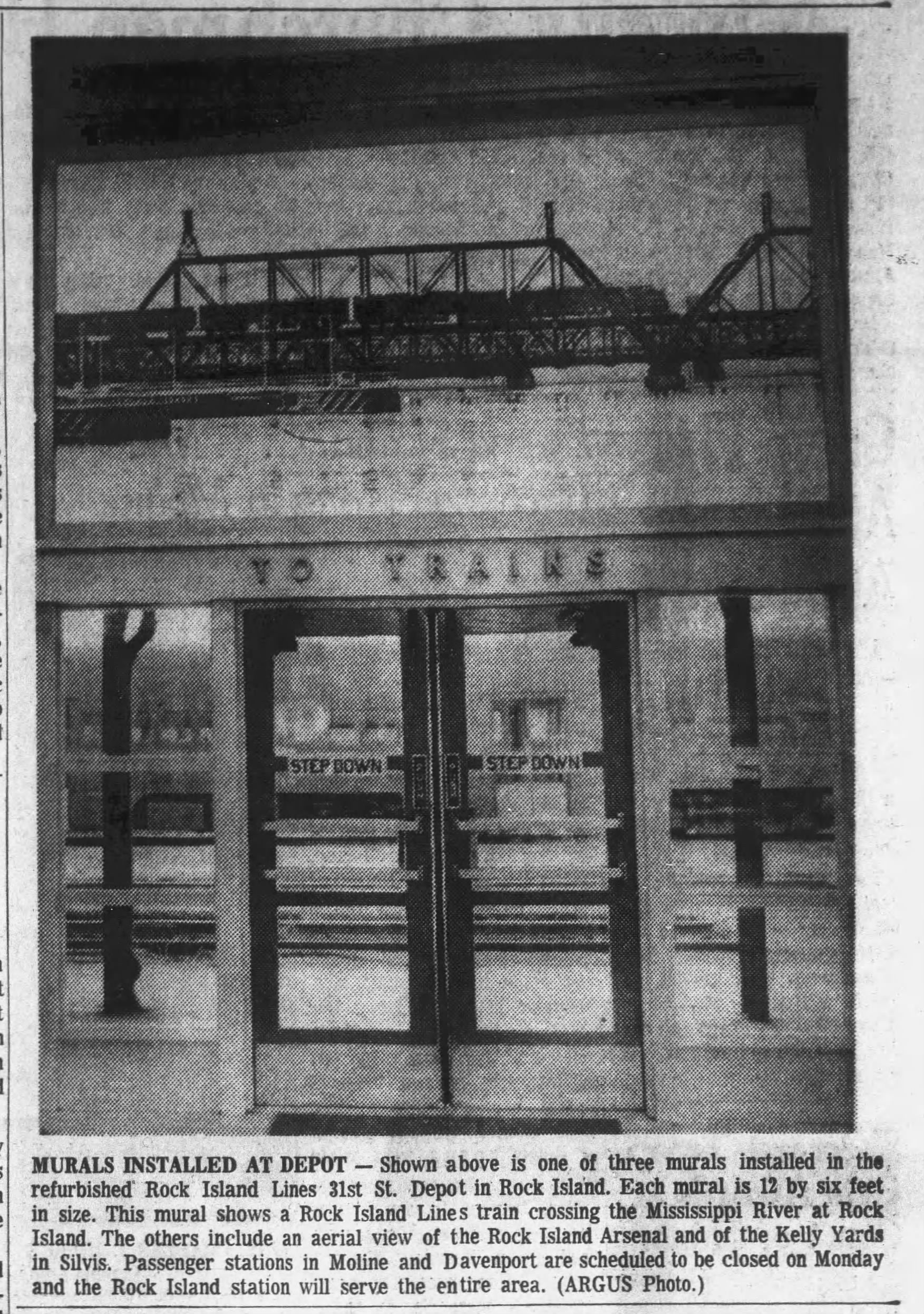

The trackage and buildings here, in Rock Island itself, were bought by the Iowa Interstate Railroad, a startup railroad which resurrected the CRI&P’s Chicago - Omaha main line. The Greater Quad City Railway Historical Society tried to open a railroad museum in the old passenger depot here in 1986, but couldn’t swing the financing. The depot and the express building stood vacant and crumbling for years until the city of Rock Island jumped in, purchasing the buildings for $8,400 in 1994. With funding from the federal government thanks to the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act, Gere-Dismer (now part of Studio483) working as the restoration architects, and presumably some tax credits from its NRHP listing in 1982, stabilization and restoration began.

After restoring the exterior, the city handed the building over to the Lemon Family, who restored and ran a hotel in Bettendorf. The Lemons completed the interior renovations, opening Abbey Station as a banquet hall in 1997. For more than 26 years now Abbey Station has been the last tangible bit of Chicago, Rock Island, & Pacific Railroad legacy in Rock Island itself–and it hosts weddings, too.

Production Files

Further reading:

- Read the National Register of Historic Places nomination yourself

- The Rock Island municipal landmark designation

- This very informative Rock Island Preservation Society blog post

- This Rock Island Argus article about its history

Member discussion: