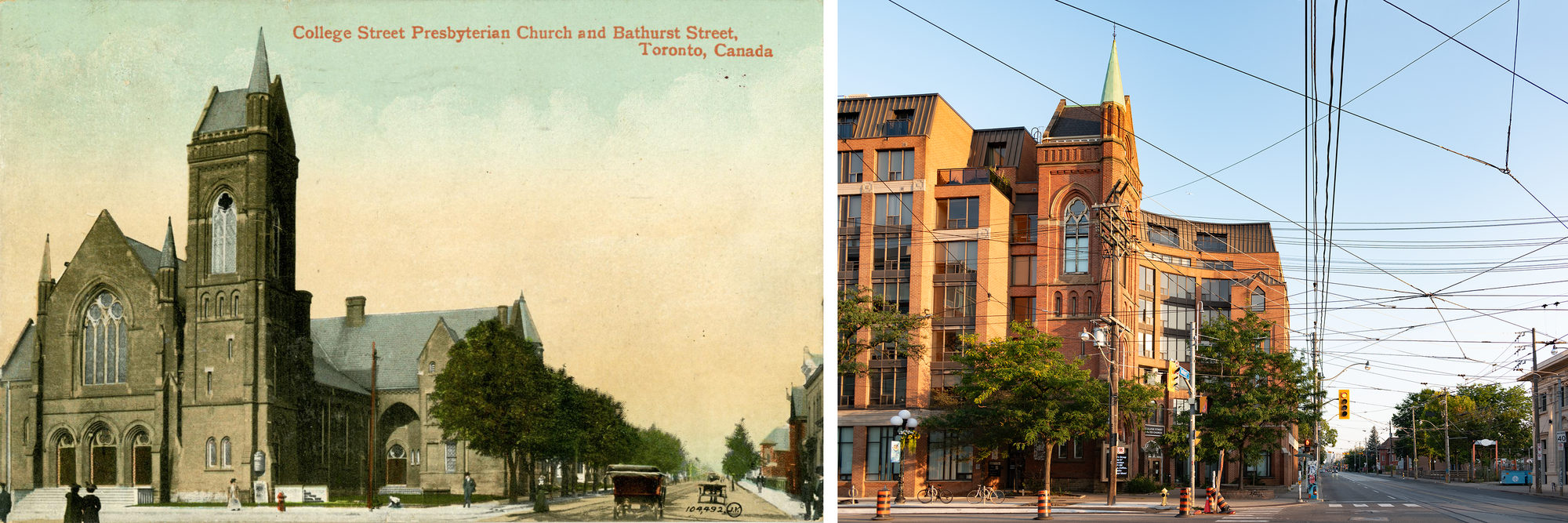

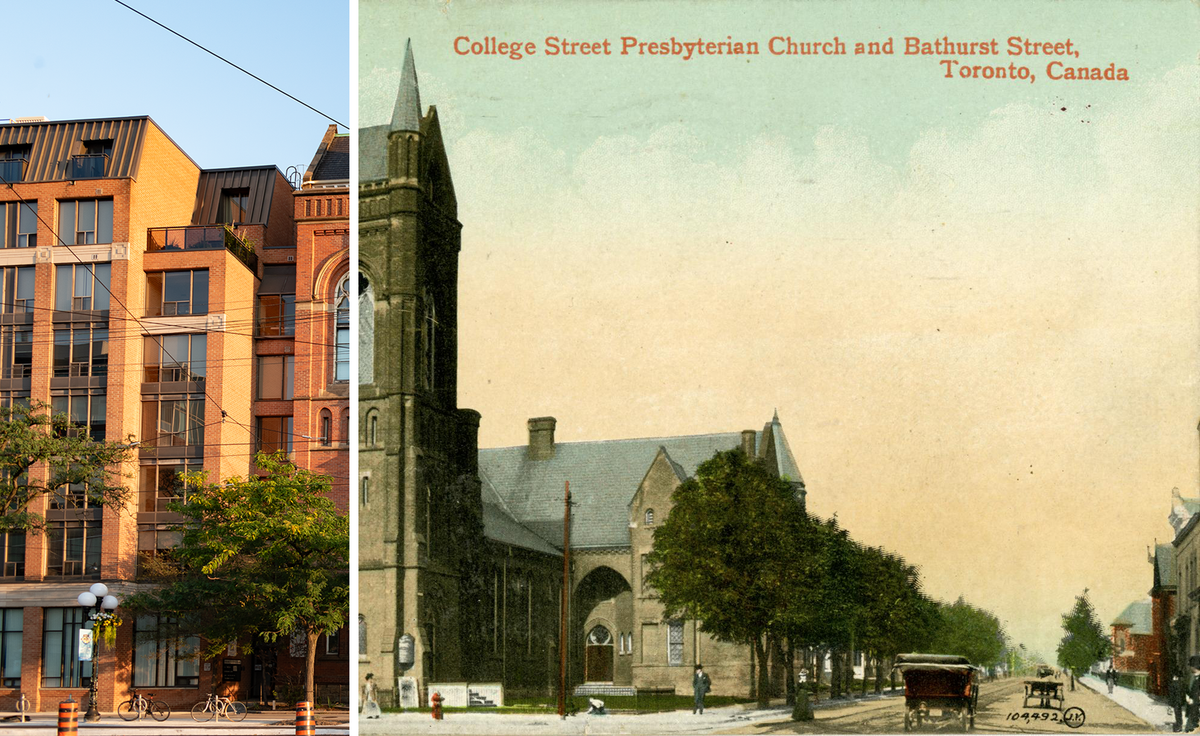

Comically clumsy, sure, but the Channel Club Condos and the College Street United Church are more interesting as an (un)holy mashup than it would’ve been as either a standard Gothic church or a teardown condo redevelopment—the kludgy result of a once-powerful congregation desperate to survive and the construction of 89 homes where there once were none. There's even a little bit of comedy here—originally marketed as the "Chanel Club Condos" at some point in the early 1990s someone slipped an extra N in there, presumably after a cease-and-desist from the French fashion house.

Completed in 1885 and designed by Smith & Gemmell, the College Street Presbyterian Church became the College Street United Church in 1925, when the vast majority of Canada’s Presbyterian, Methodist, and congregational churches voted to unite. Despite a deeply contentious redevelopment process, the church was mostly demolished in 1988—a 1986 conservation listing “saved” the tower portion.

So, what's changed? Well. lol. lmao.

(also there were definitely overhead catenary wires on College Street when this postcard was published in the 1910s, they were just airbrushed out)

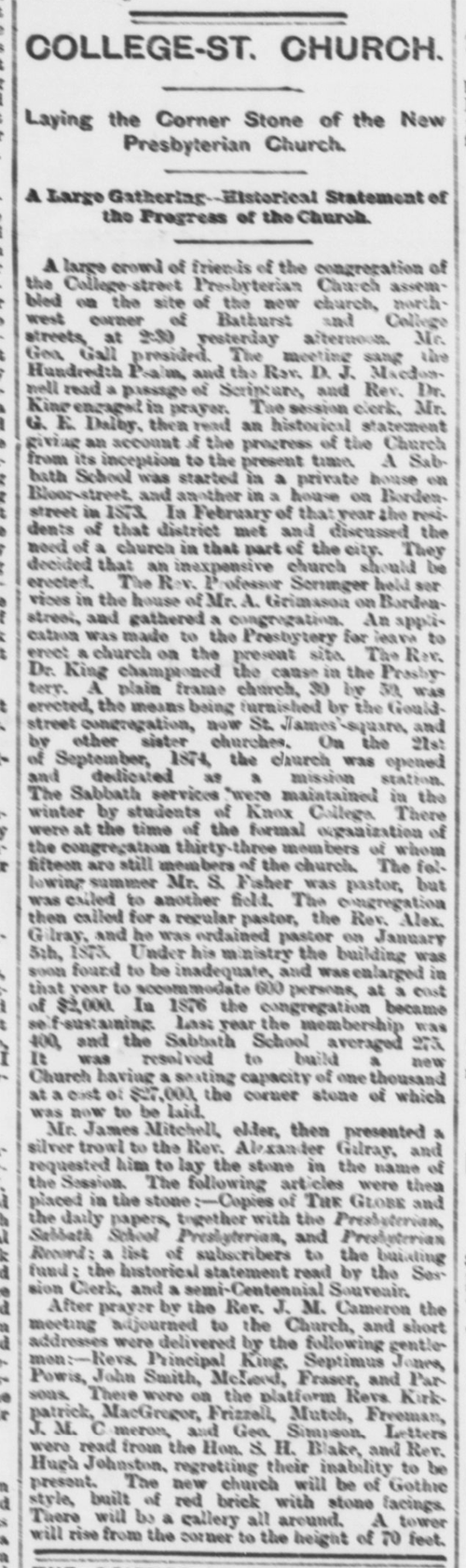

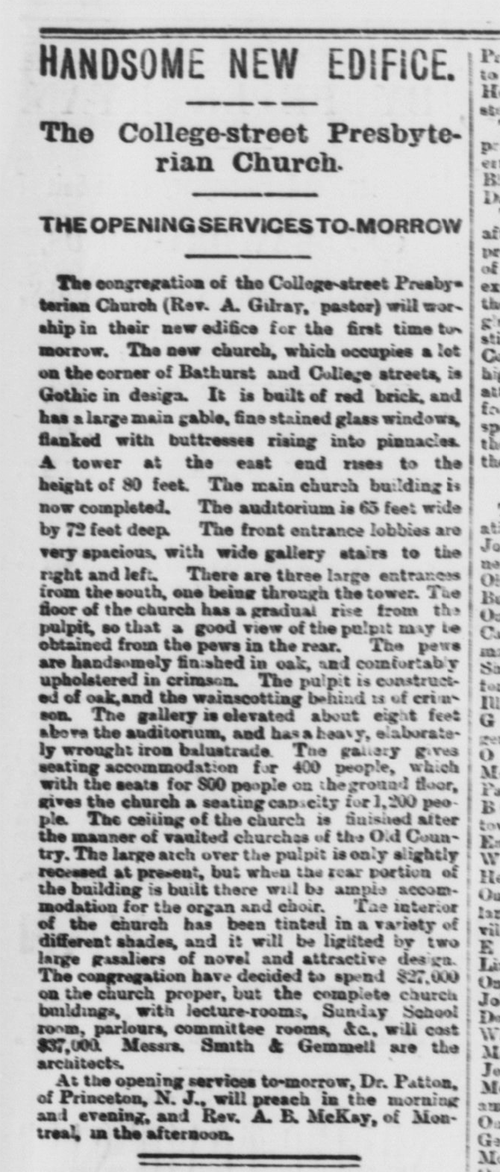

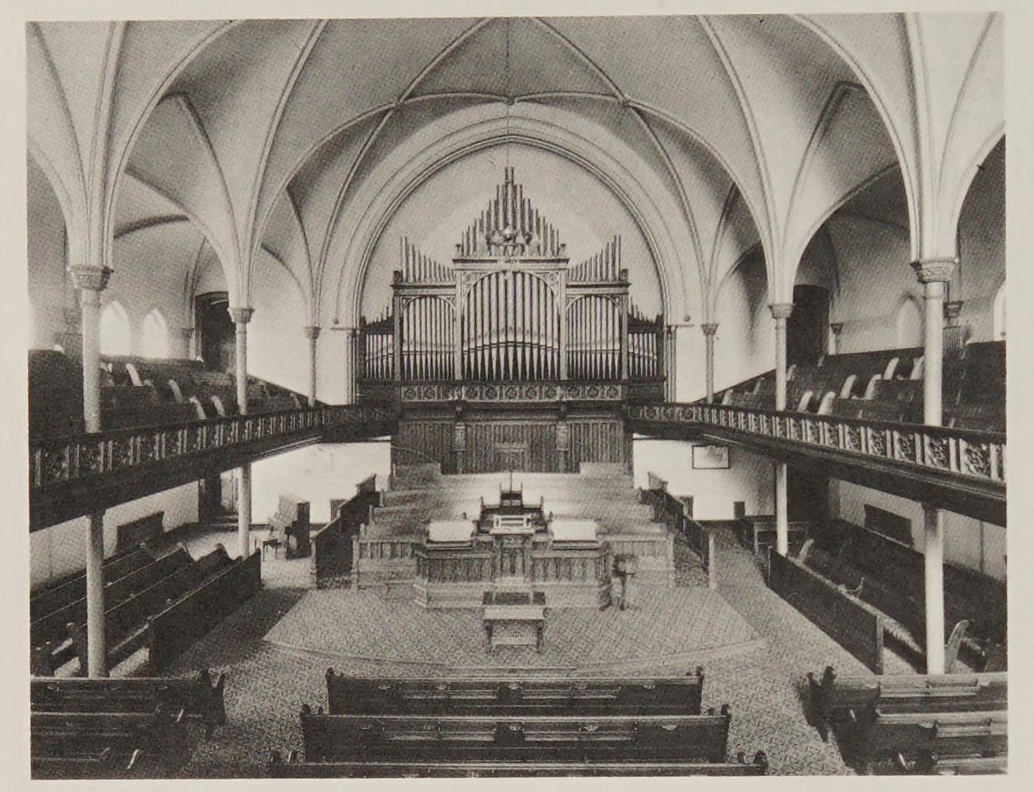

Part of Toronto’s third wave of church building, an ambitious Presbyterian congregation led by Rev. Alex Gilray hired the Toronto firm of Smith & Gemmell to build them an august new home on College Street. Opened in 1885, within a decade the congregation had rehired the architects to expand their building—the sanctuary had room for more than 1200 people. Gothic revival, a later critic would describe it as a “rather undistinguished Victorian pile”.

Cornerstone laying, 1884 | Opening, 1885 | Rev. Alexander Gilray, Presbyterian Pioneer Missionaries in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia, the Internet Archive

In 1925, the College Street Presbyterian Church voted 1,027 to 360 to unite with the Methodists and Congregationalists to form the United Church of Canada, joining the two-thirds of Canadian Presbyterian congregations that voted for union, and so the College Street Presbyterian Church became the College Street United Church.

1925, union vote and membership | 1937, in the background, Toronto Public Library | 1927, anniversary | 1938, interior | 1948, organ ad

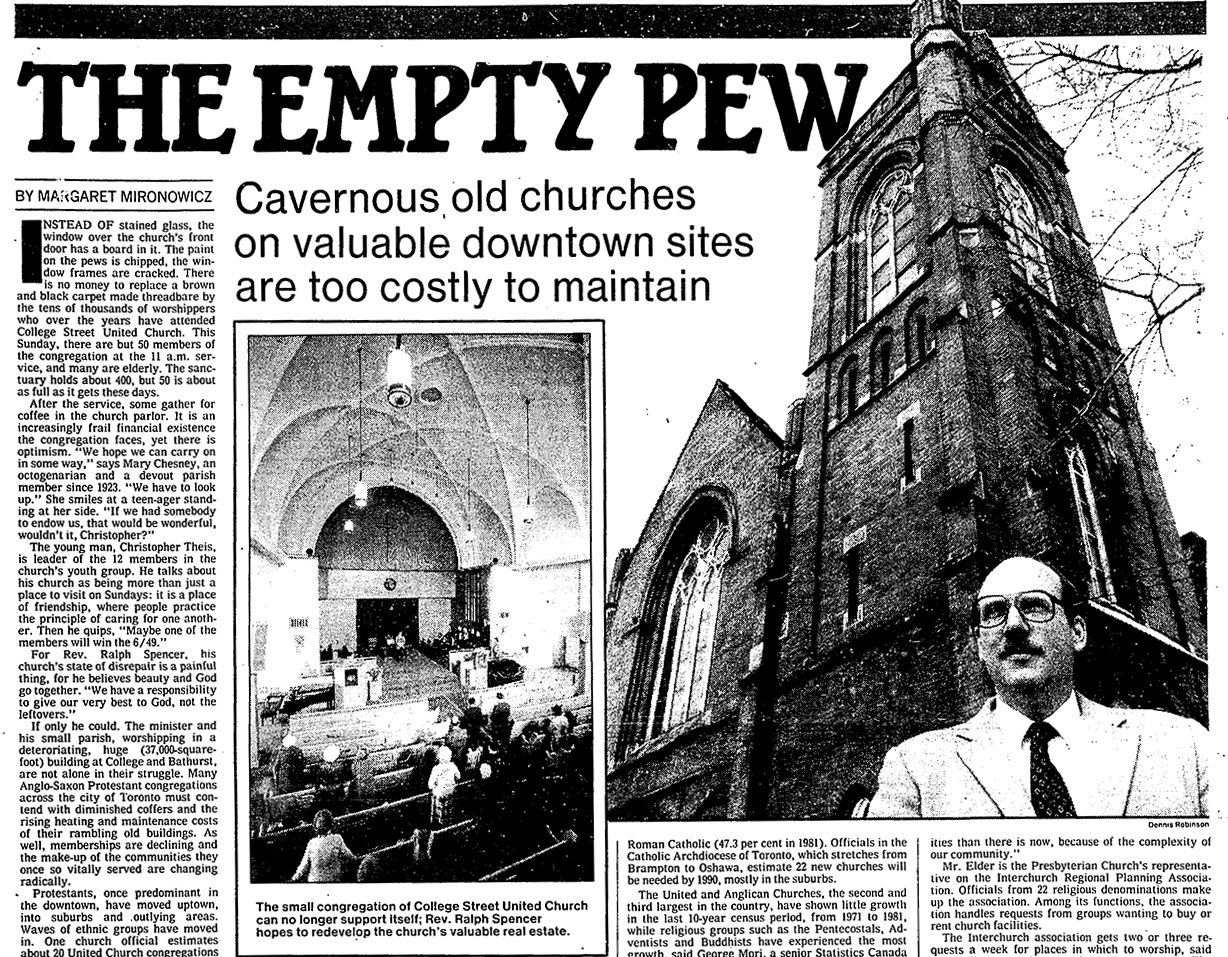

In retrospect, the union represented the College Street United Church’s membership peak. The congregation—which had 2,000 members in 1925—had dwindled to only 125 members in 1985.

It was a familiar story—a shrinking church straining under the weight of maintaining a crumbling, century-old pile built for a much larger congregation. However, unlike its peers in disinvested parts of American cities or the emptied-out quarters of rural North America, the College Street United Church had a valuable asset that could, if they played their cards right, guarantee the church’s future—their land. With Toronto in the midst of a (still mostly uninterrupted) development boom, Rev. Ralph Spencer embarked on a nearly ten-year-long development process that would—if successful—secure the congregation a new right-sized space (and maybe even a nice profit).

1956, James V. Salmon, Toronto Public Library | 1982, Roberto Lissia, Toronto Public Library | 1985 article about empty churches

To guarantee the church's future, Rev. Spencer proposed selling the old College Street United Church on the condition that any developer reserve them permanent space in the new development. He initially pursued plans to demolish the church for a medical arts office complex before pivoting to the condo plan. Alderman Dale Martin, the Toronto Historical Board, and even some other United Church congregations opposed Rev. Martin’s plan, castigating him for focusing on market-rate rather than affordable housing and “using church property for profit”.

…I don’t think the profit came, in the end. The redevelopment process was a long one. In 1986, the deteriorating building was designated under the Ontario Heritage Act, but with the redevelopment plans already underway, I suspect this was more a negotiating tool than a pure preservation play—the conservation listing gave the city a leverage point. That summer, the City of Toronto rejected the owner’s application to demolish the building, before turning around and approving the partial demolition that spared the tower a few months later.

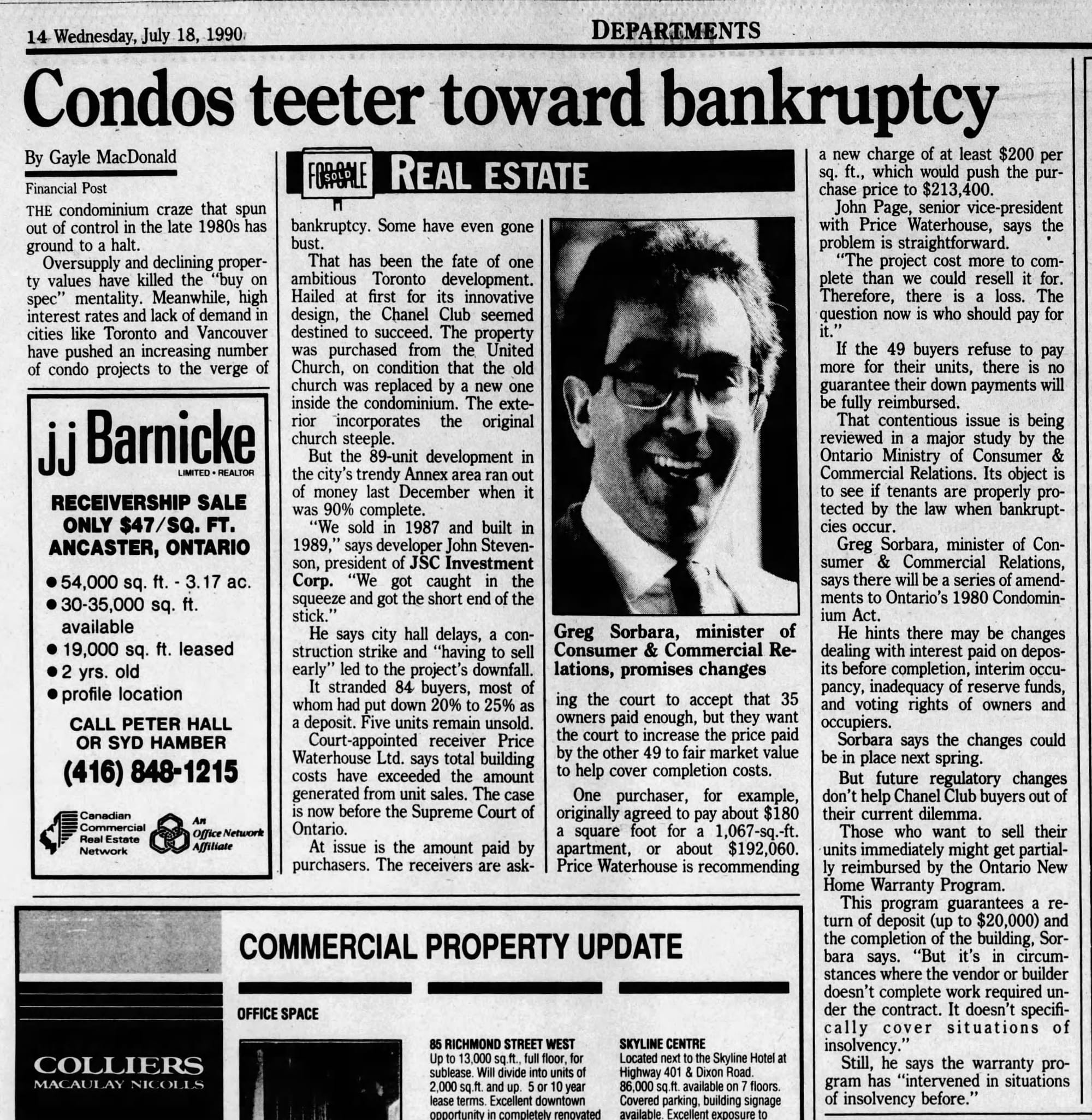

1986 heritage designation | 1986 demolition refusal | 1986 partial demolition approval | 1988 condos for sale | 1990 condo bust | 1990 church dedication | 1990 architectural criticism | 1990 receivership sale

Designed by Brian Luey of Carson Woods Architects, the developer–JSC Investments–started selling units in the condo redevelopment in 1987. Two years later the developer went bankrupt with the project 90% finished—it sounds like everyone took a bit of a bath, but the College Street United Church eventually did end up with a more manageable new home. Originally marketed as the “Chanel Club Condos”, at some point in the early 1990s someone quietly stuck an extra “n” in there, implying they received a cease-and-desist from the French fashion house, which cracks me up.

The Channel Club Condos and the College Street United Church might not strike the most elegant balance of architectural preservation and new housing, but they make legible a bunch of the compromises that accumulate in the redevelopment process—the existential decisions that face a shrinking church, how a congregation (and a city) balances profit and preservation, and the tumultuous impulses of the real estate market. It might be clumsy and confused, but at least it’s interesting—and from the perspective of the College Street United Church, it's clearly worked. The progressive Protestant congregation, once known as "The Church of the Open Door" continues to worship on the corner of Bathurst and College.

Production Files

Further reading:

- In their own words, the College Street United Church

- Enduring Witness: a history of the Presbyterian Church in Canada, by John S. Moir

- Altared places : the reuse of urban churches as loft living in the post-secular and post-industrial city by Nicholas Andrew Lynch

- The Growth of the Industrial City and Inner Toronto's Vanished Church Building by Jon Caulfield

If you’re absolutely desperate to see some intact ecclesiastical work from Smith & Gemmell, don’t fret. They were a busy firm in a growing Toronto in the 1880s and 1890s, and their Church of the Redeemer still stands on Bloor. They also designed the Architecture Faculty building at the University of Toronto (originally Knox College) and the Lager Brewery Building on River Street.

Member discussion: