Soon after first firing the crematorium here in 1909, the management at Oak Woods Cemetery turned around and instituted a color line—racist even in death, “we only burn white bodies here”. Today it’s the cemetery of choice for Chicago’s Black elite, but from the 1910s to the 1960s Oak Woods was—with a few notable exceptions like Ida B. Wells and Jesse Binga—a white-only cemetery.

Tearing down the cemetery’s color line took more than a decade of try-everything, kitchen-sink activism led by Black funeral directors like Marshall Bynum and A.R. Leak along with faith leaders. Poking and prodding for weaknesses and pressure points, they made a spectacle out of being refused use of the crematorium across races (Black undertaker, Black body? Denied. Black undertaker, white body? Denied). They passed city ordinances and state legislation and filed lawsuit after lawsuit. In 1963, they organized a protest attended by thousands. Ultimately, the pressure from the multipronged approach combined with overwhelming changes to the demographic-economic structure of the neighborhood around Oak Woods (which went from 6% Black in 1950 to 86% in 1960), and the cemetery desegregated in the mid-1960s.

So, what’s changed?

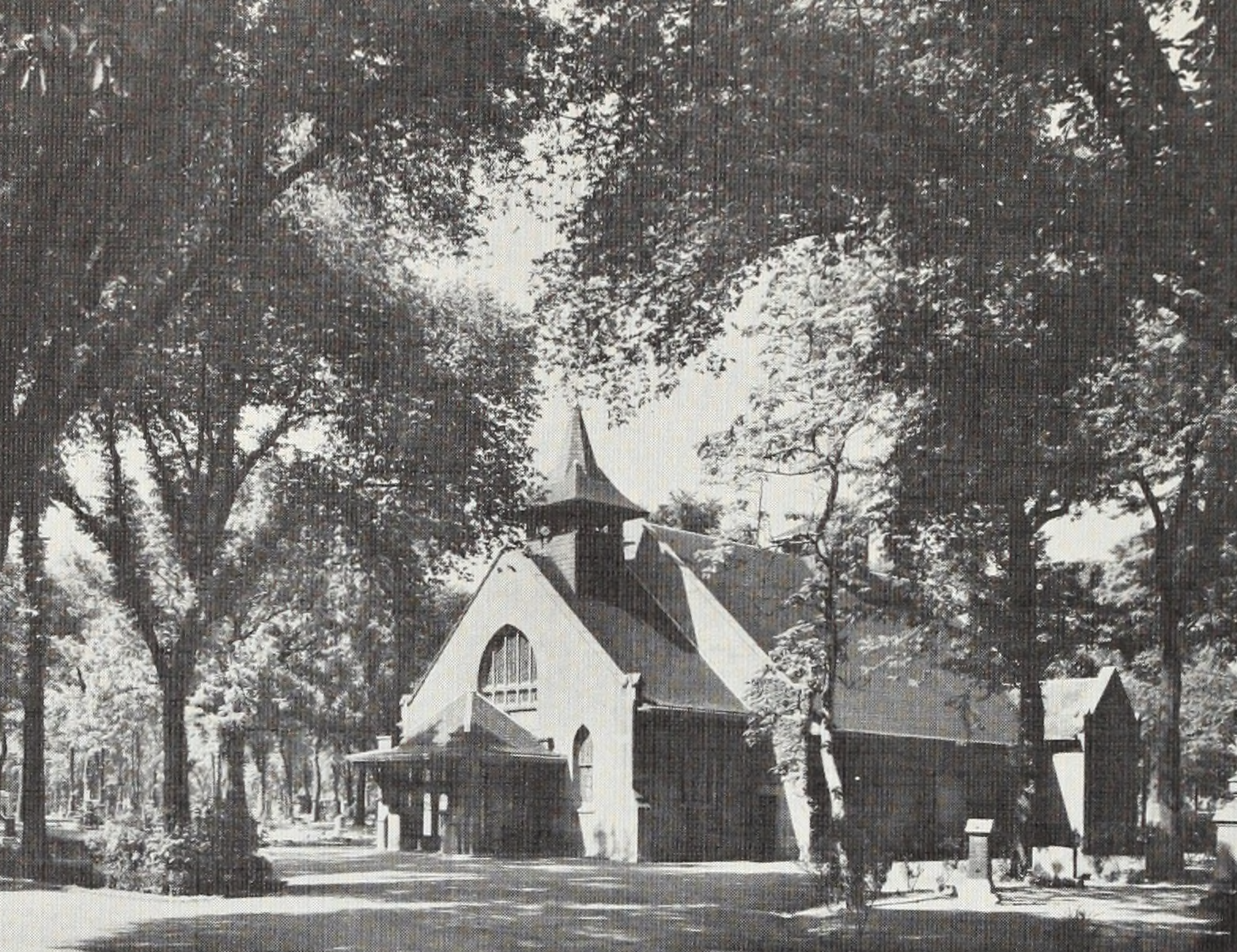

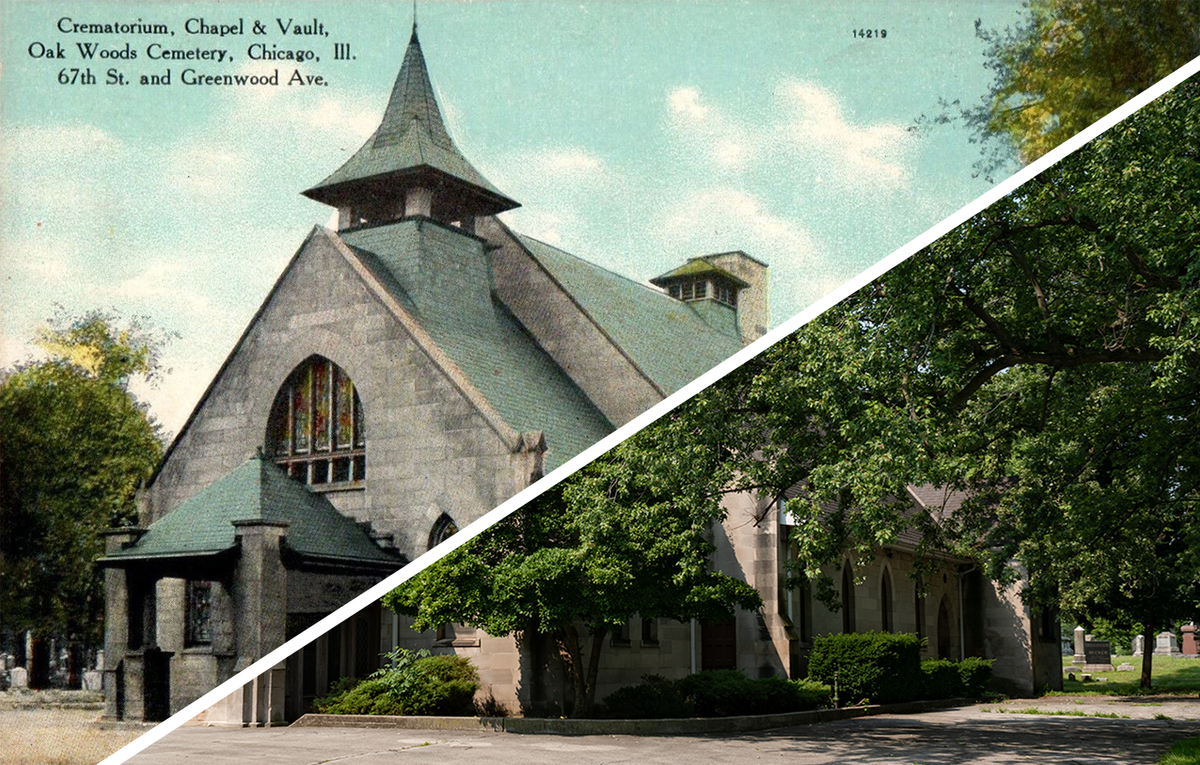

- They walled in the chapel’s porte-cochère at some point, turning it into an indoor foyer instead, and extended the curbs to its edge. Since it predates real automobile usage—it was built in 1903—I imagine it was too small for modern vehicles by mid-century.

- The chapel’s stained glass is still there, but it’s been covered with a protective layer that partially obscures it on the exterior.

- 110+ years of tree growth, look at ‘em go.

So not so much, superficially, but that superficial continuity conceals a century of social upheaval.

1905, W.C. Zimmerman appointed Illinois State Architect | 1909 ad in the Chicago Tribune | 1910 photo from Park and Cemetery, the Internet Archive | 1911 photos of the crematorium from Park and Cemetery, the Internet Archive | 1910 Chicago Tribune article about the proliferation of cremation and the operations at Oak Woods

Chartered in 1853, Oak Woods received its first burials in the 1860s. Some forty years later, by then the South Side’s premier cemetery, Oak Woods hired architect William Carbys Zimmerman to design this chapel, which opened in 1903*.

Running a busy practice from the late 1890s into the 1920s—including a stint as Illinois State Architect—Zimmerman designed homes, civic buildings, and industrial facilities across Chicagoland and the Midwest. Perhaps most notably, Zimmerman’s firm designed the fieldhouses at Dvorak Park, Eckhardt Park, Holstein Park, and—their best—Pulaski Park. Zimmerman practiced at the hinge of revivalist styles and more modern American movements like the Prairie Style and the Arts & Crafts movement, a dynamic hinted at here, with Zimmerman designing a little English Gothic village chapel with a trace of Prairie Style.

(*tbh I’m a little unconvinced on this dating—I can’t find contemporaneous sources or the permit and articles from 1910 call it “their new vault and chapel building” which seems like a weird thing to say about a seven-year-old building)

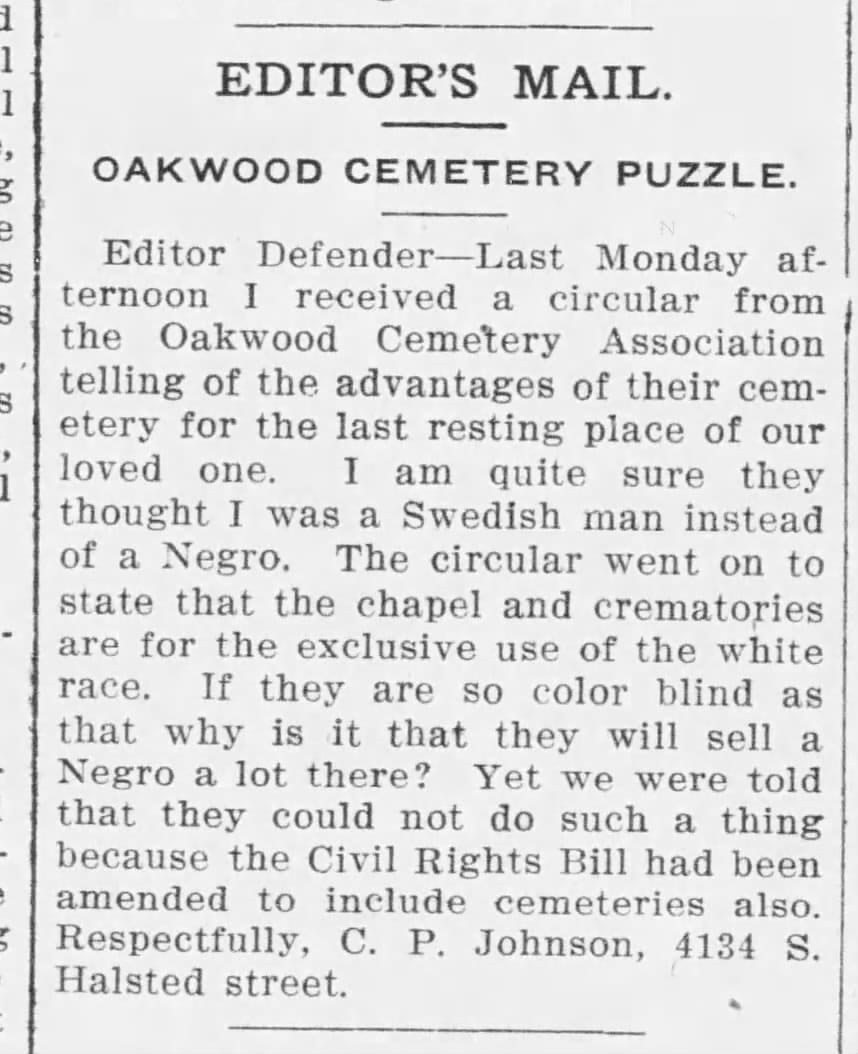

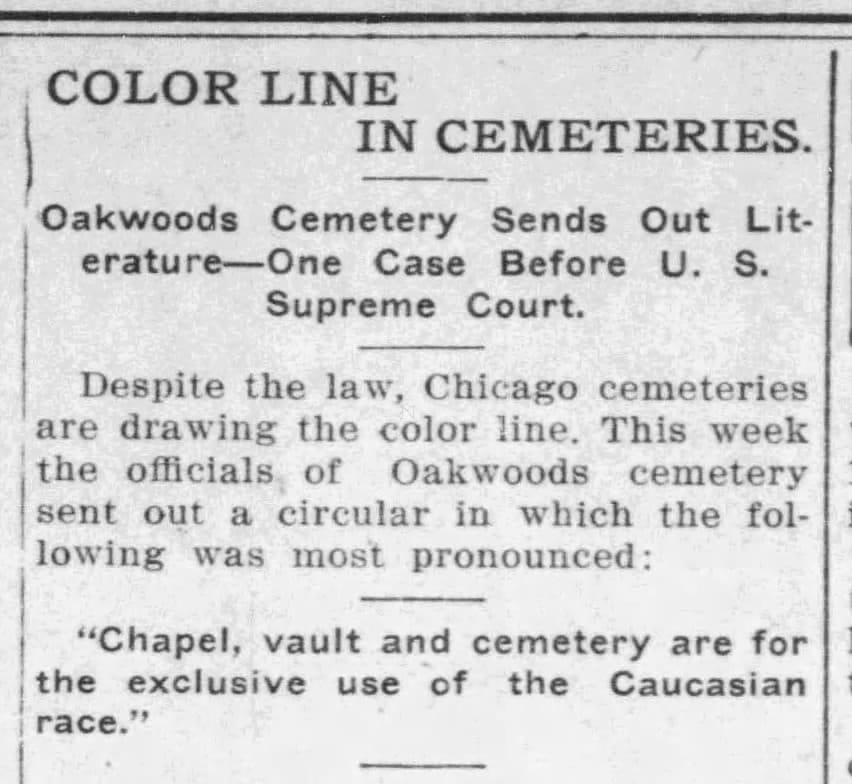

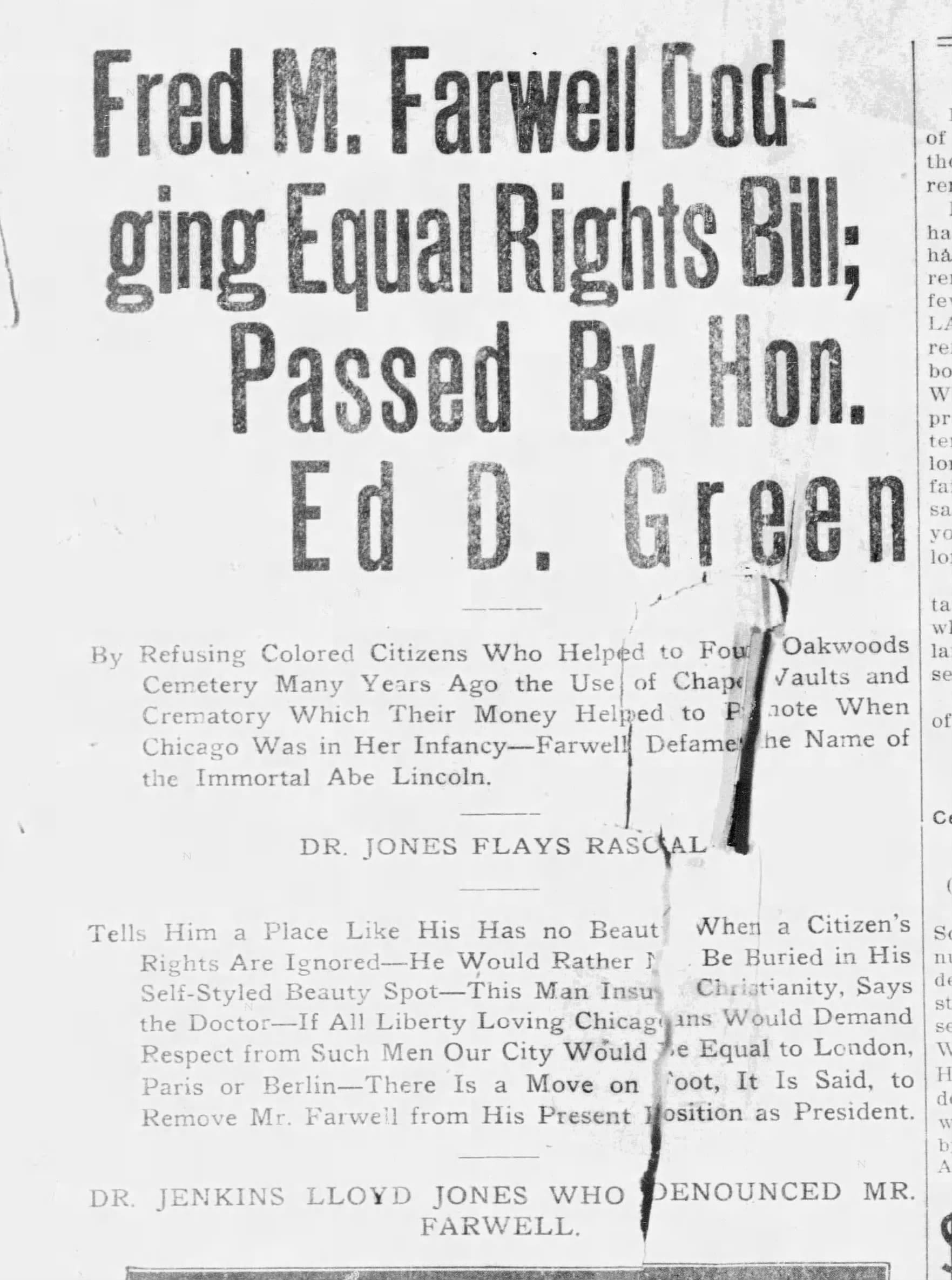

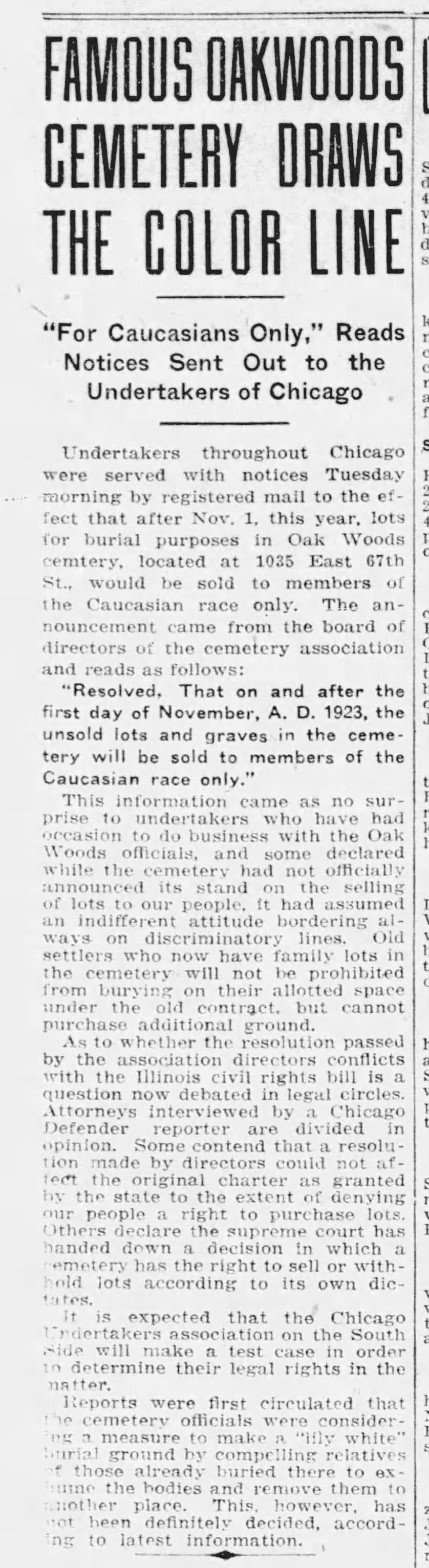

1910-1923 articles about racial discrimination and the color line at Oak Woods in the Chicago Defender

In 1909, Oak Woods turned on their cutting-edge new crematorium—they made a lot of noise about how it was the only one that exclusively burned natural gas in the US—and quickly decided that only white bodies would be cremated here. Oak Woods appears to have been lazily integrated initially (it doesn’t mean much to be integrated in 1900 when Black people made up less than 3% of Chicago’s population). However, as the Great Migration grew the city’s African American population in the 1910s, Oak Woods management—led by Superintendent Edward G. Carter—started erecting racist barriers to keep Black people out of the cemetery. They started with price gouging and shitty service, followed by racist anti-marketing (they literally sent out mailers saying the chapel, crematorium, and cemetery were for white people only), and eventually formalized the color line in 1923, decreeing that “unsold lots and graves will be sold to members of the Caucasian race only”.

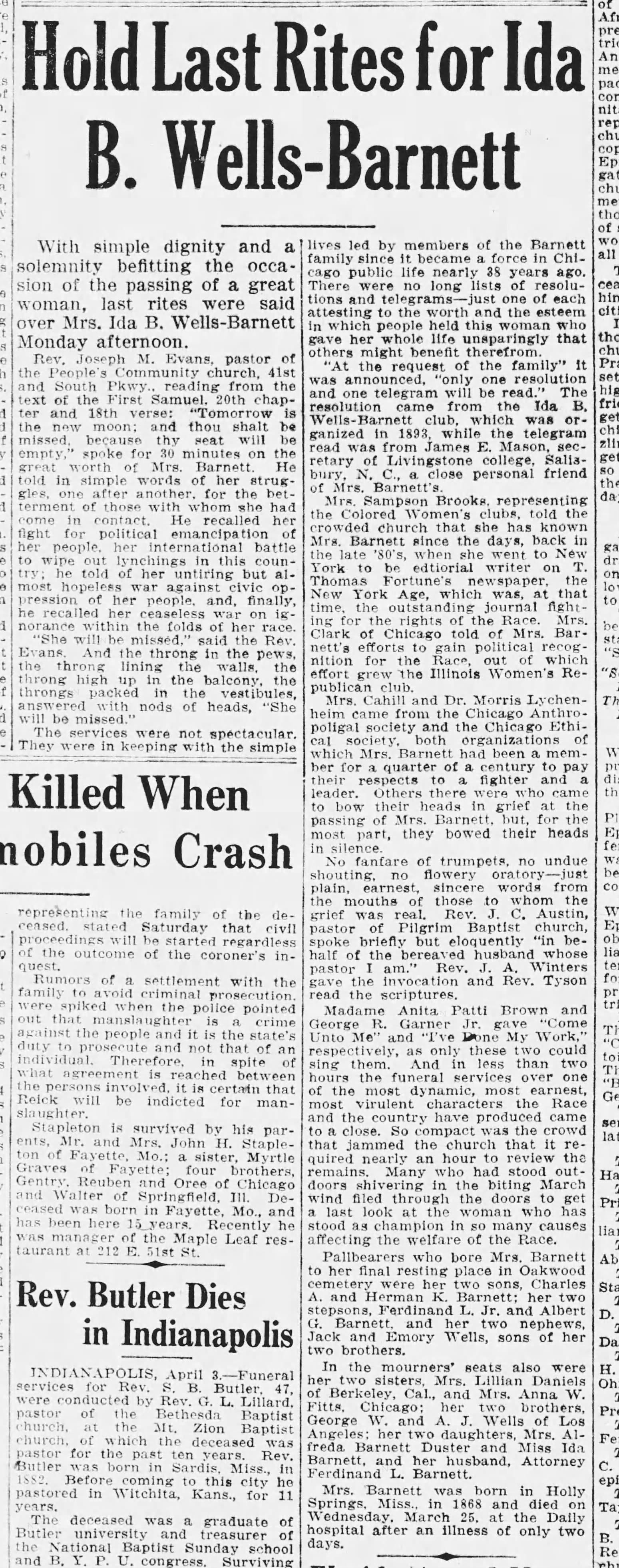

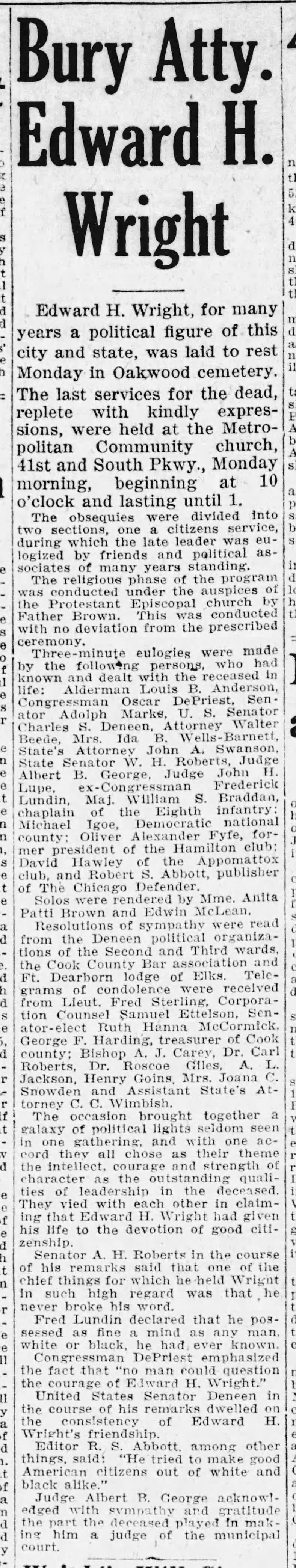

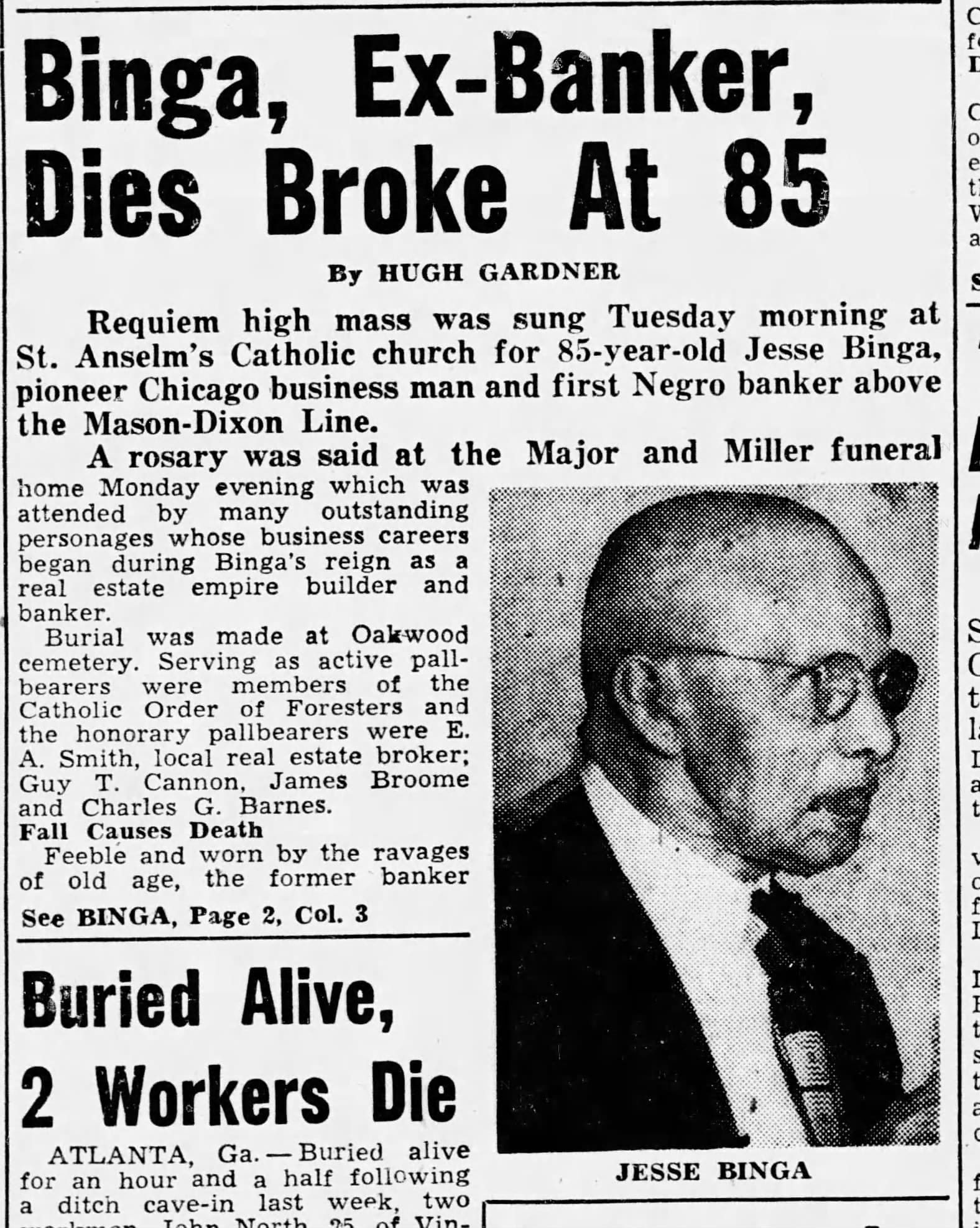

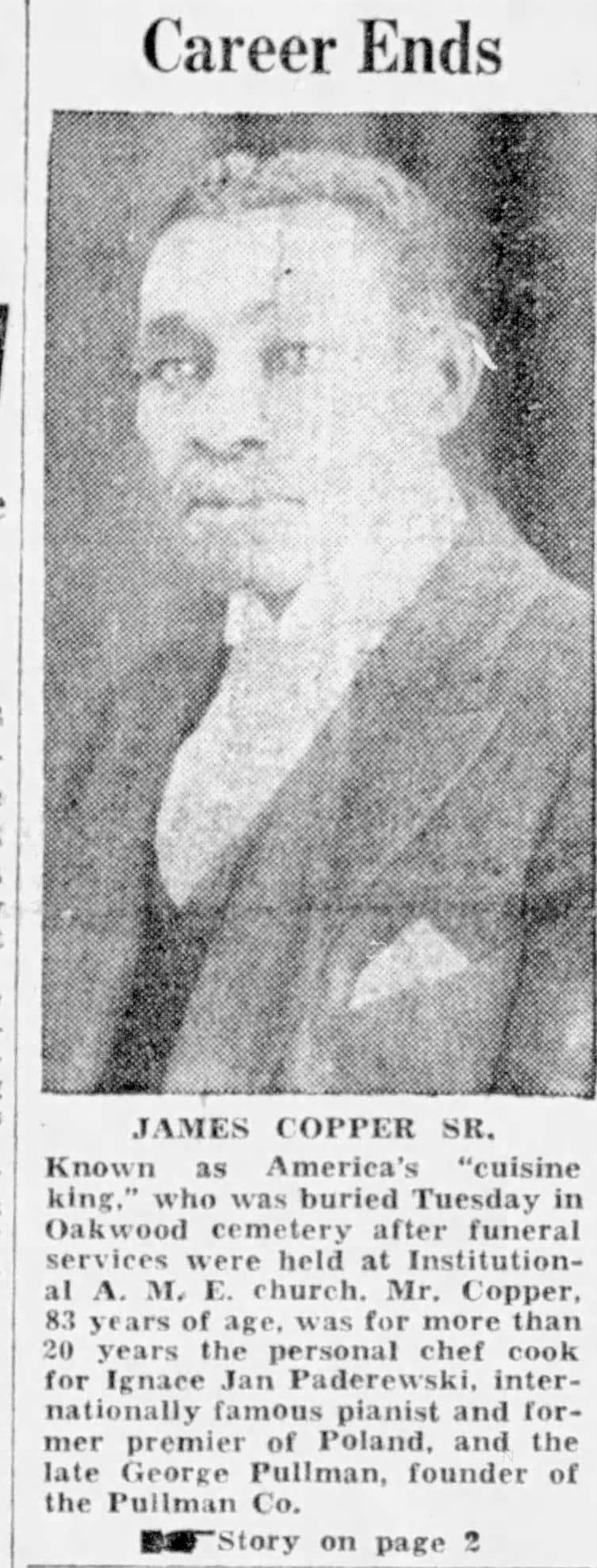

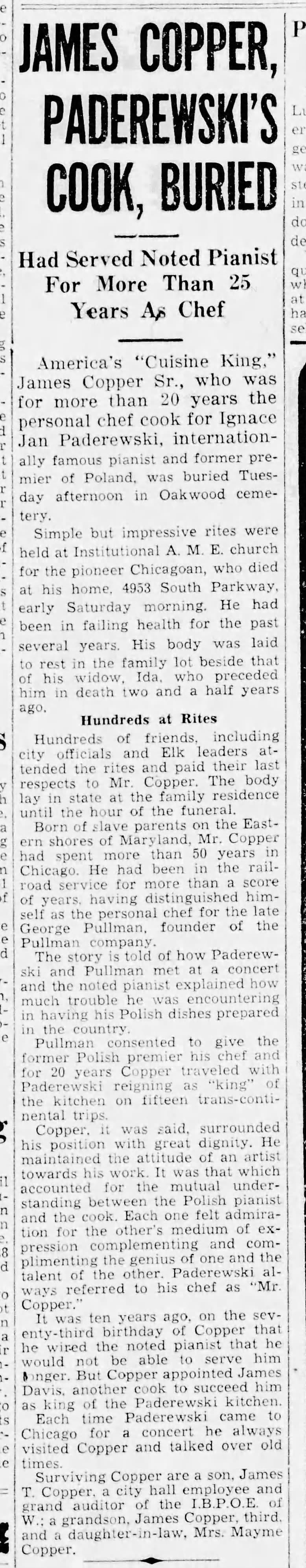

The Black community vigorously protested the discriminatory policies—the city’s Black Belt was just north of Oak Woods, so this would have been their local cemetery—but the new color line held. Black families who had purchased plots before the ban could still be interred at Oak Woods, as well as anyone who could find a white person to purchase a plot on their behalf. Journalist Ida B. Wells, businessman Jesse Binga, and politician Edward Wright were among those buried here while Oak Woods was a segregated cemetery. My favorite might be James Copper, a cook for the Pullman Company who served as the personal chef for Ignacy Jan Paderewski, a renowned concert pianist and the Prime Minister of Poland (fascinated by what that relationship would have been like).

1931, Ida B. Wells buried at Oak Woods | 1930, Edward H. Wright buried at Oak Woods | 1950, Jesse Binga buried at Oak Woods | 1912, Eudora Johnson-Binga buried at Oak Woods | 1937, James Copper buried at Oak Woods

Black people without a grandfathered plot or white connections mostly ended up at burial grounds outside the city—Lincoln Cemetery in Blue Island, Burr Oak in Alsip, or Mt. Glenwood in Glenwood (Catholic cemeteries in the city did accept African American Catholics). That distance added a time and a travel tax for the vast majority of Chicago’s Black population when visiting their departed relatives.

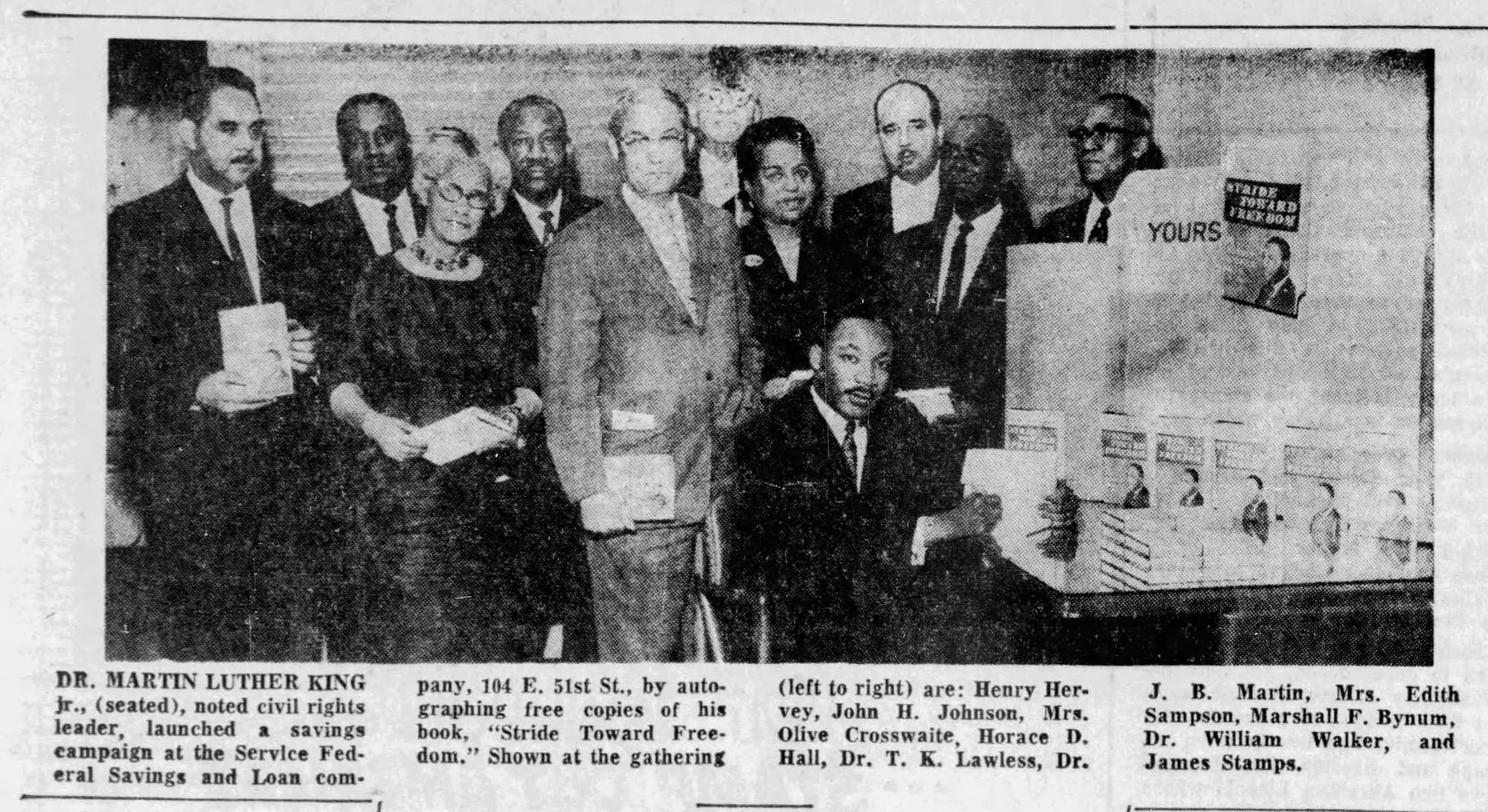

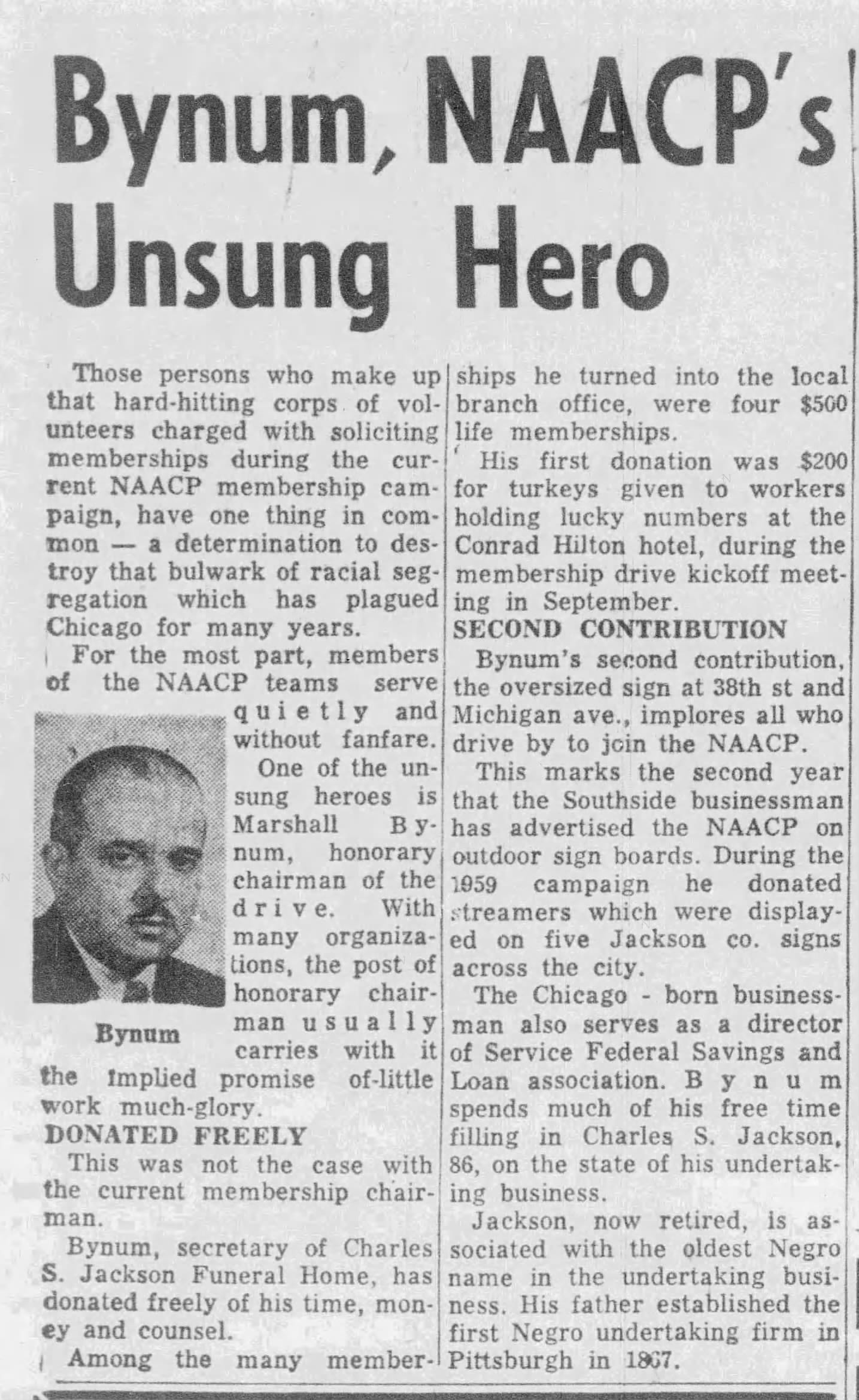

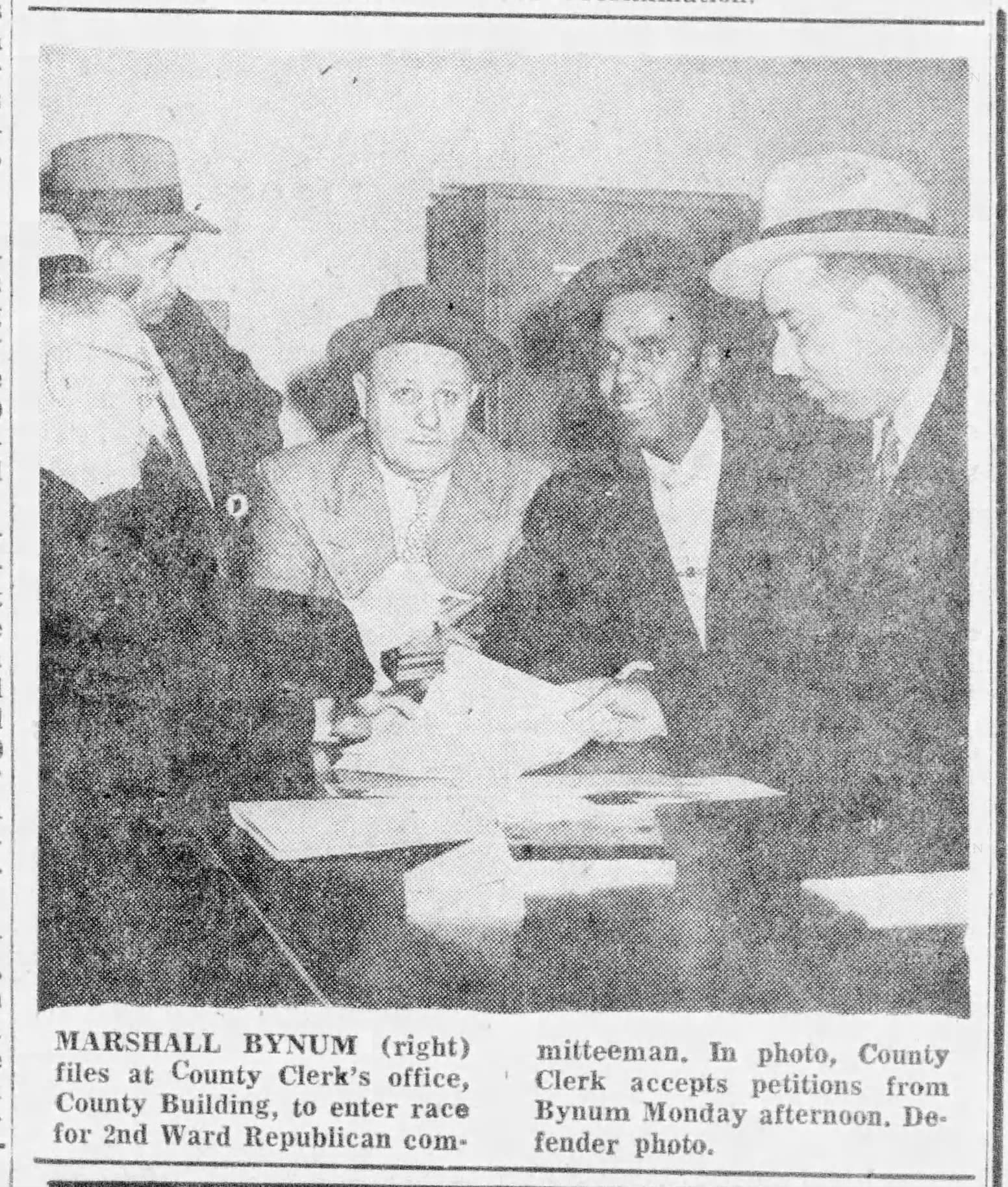

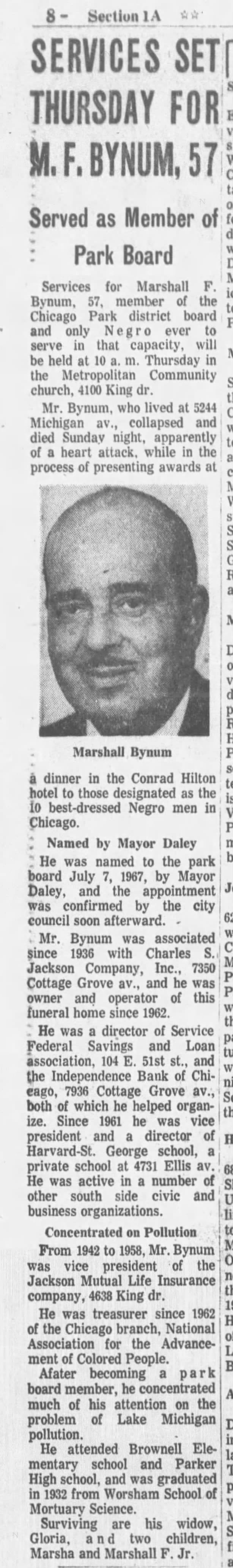

With the Civil Rights Movement picking up momentum in the 1950s, funeral director Marshall F. Bynum started chipping away at the color line at Oak Woods. Bynum was a bigwig in the Chicago branch of the NAACP, as well as an executive at the Charles Jackson Funeral Homes. There was both a moral and practical angle to his activism—Charles Jackson Funeral Homes had a location a few blocks away from Oak Woods, but because of the cemetery’s racist policies, they had to go all the way up to Graceland Cemetery on the North Side to use their crematorium.

1955 photo, the Internet Archive | 1955, Bynum attempts to cremate James Pickens at Oak Woods, Chicago Defender | 1958, Bynum attempts to cremate Helma McBowe at Oak Woods, Chicago Defender | 1959, Bynum attempts to cremate George Harney at Oak Woods, the Chicago Defender | 1959 article in the Chicago Defender

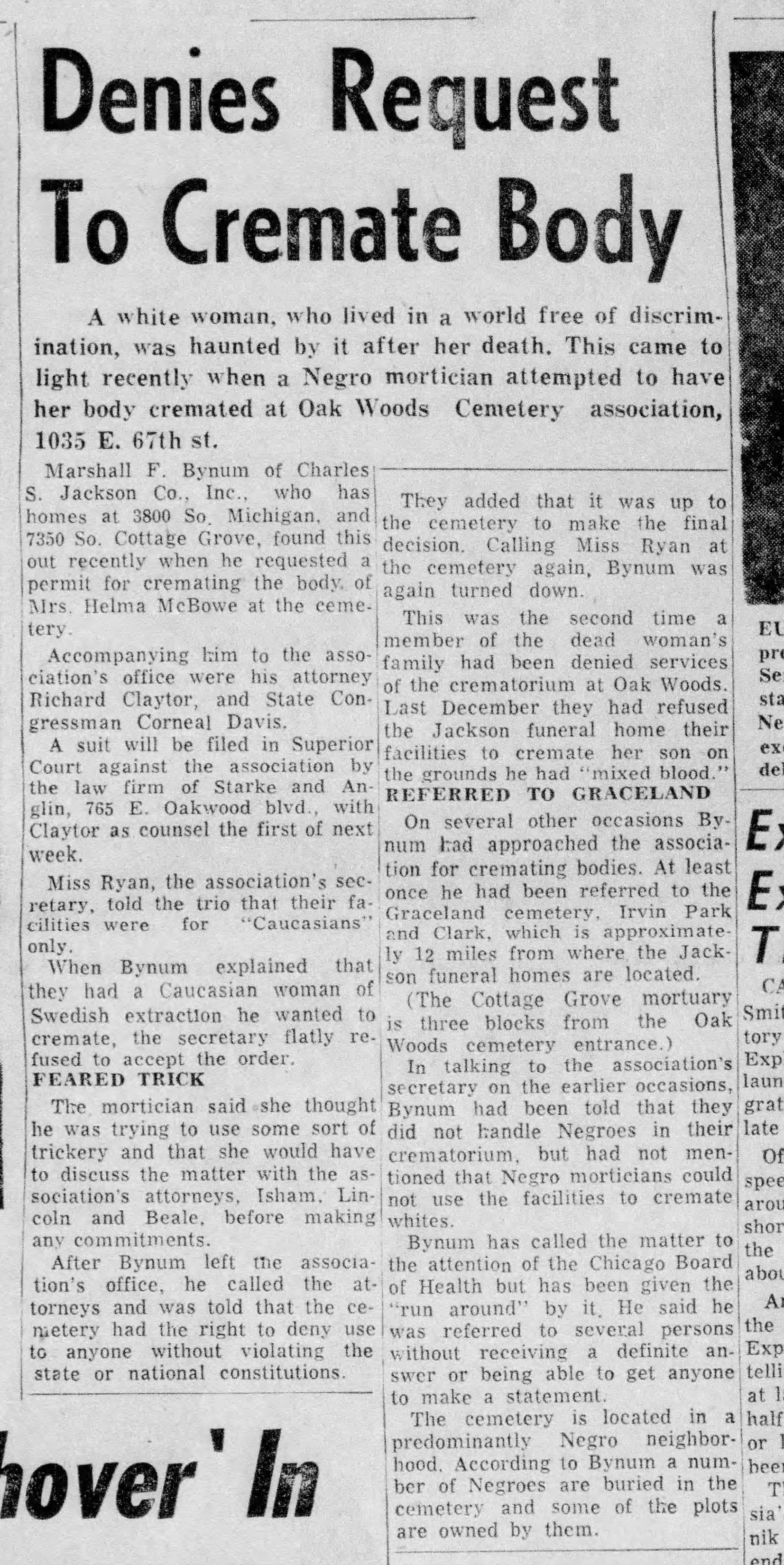

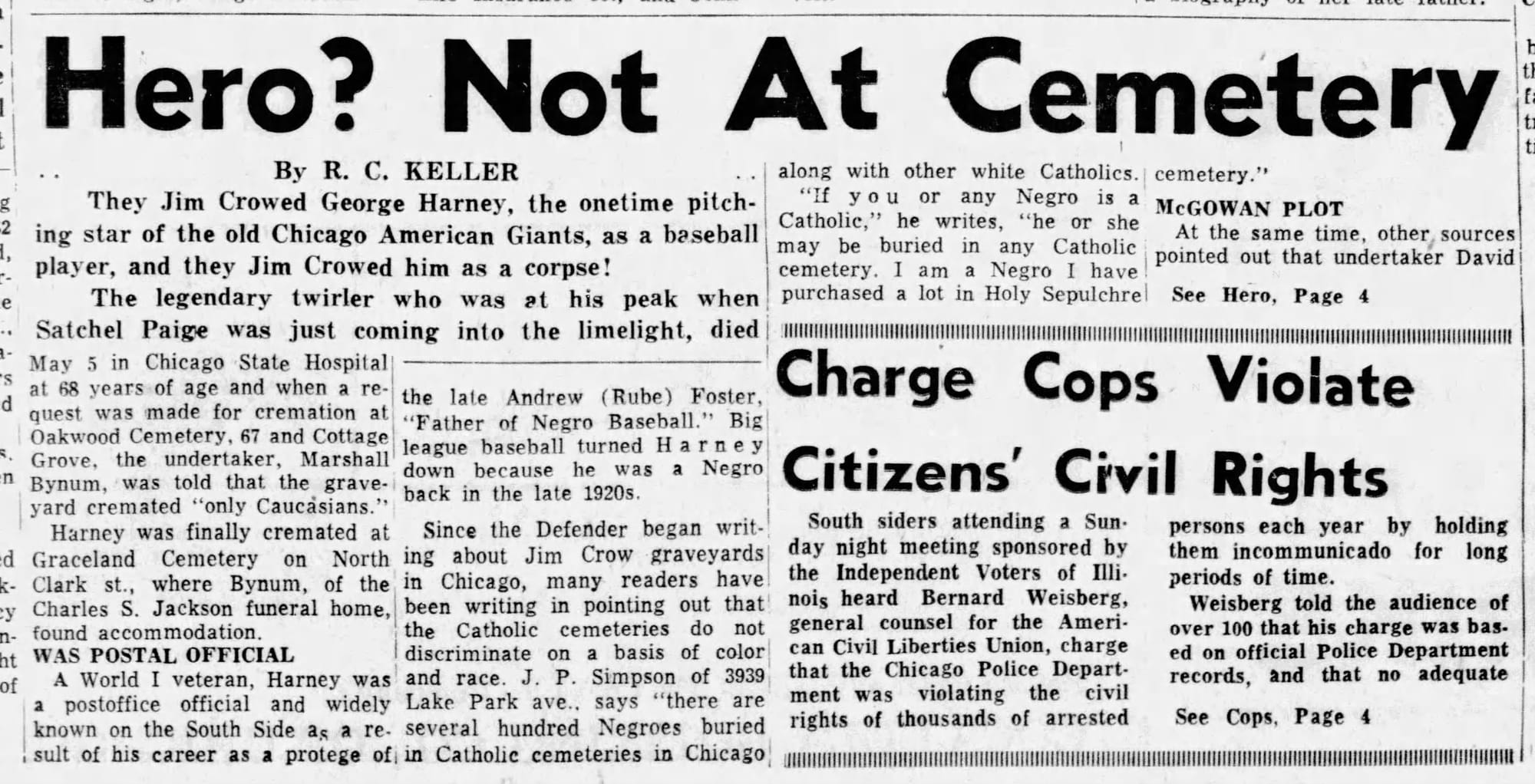

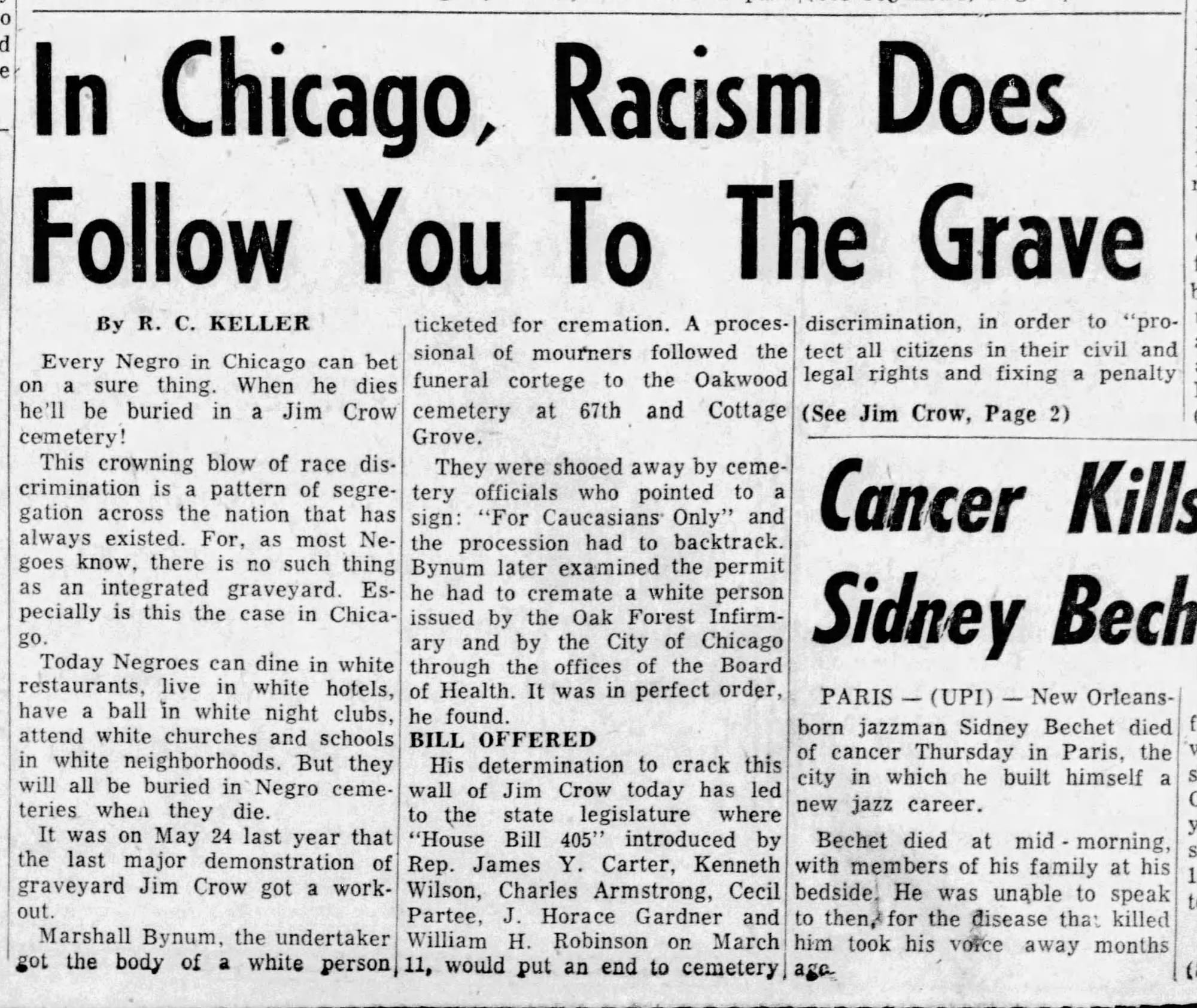

Bynum started hitting Oak Woods by creating a spectacle around getting turned away by their crematorium. In 1955, he attempted to cremate the body of a Black man, James Pickens, at Oak Woods—rejected. In 1958, he tried to cremate the body of white woman, Helma McBowe, at Oak Woods—denied, no Black morticians allowed. In 1959, trying the respectability and fame route, he tried to cremate the body of George Harney, a World War I veteran and former Negro Leagues star—rejected again (Harney is interred at Graceland).

(A quick aside on Helma McBowe: a Swedish immigrant who married the Kentucky-born Sydney McBowe, the family lived on the edges of the Black Belt. Sydney was a white-passing mixed-race man, meaning Helma was in an interracial marriage at a time when that was still illegal in much of the US. A year before Helma passed away, Oak Woods even turned away the body of their son, Edwin, because of his "mixed blood". Hard not to ascribe a poignant political meaning to Helma, even in death, striking a blow at a racist color line.)

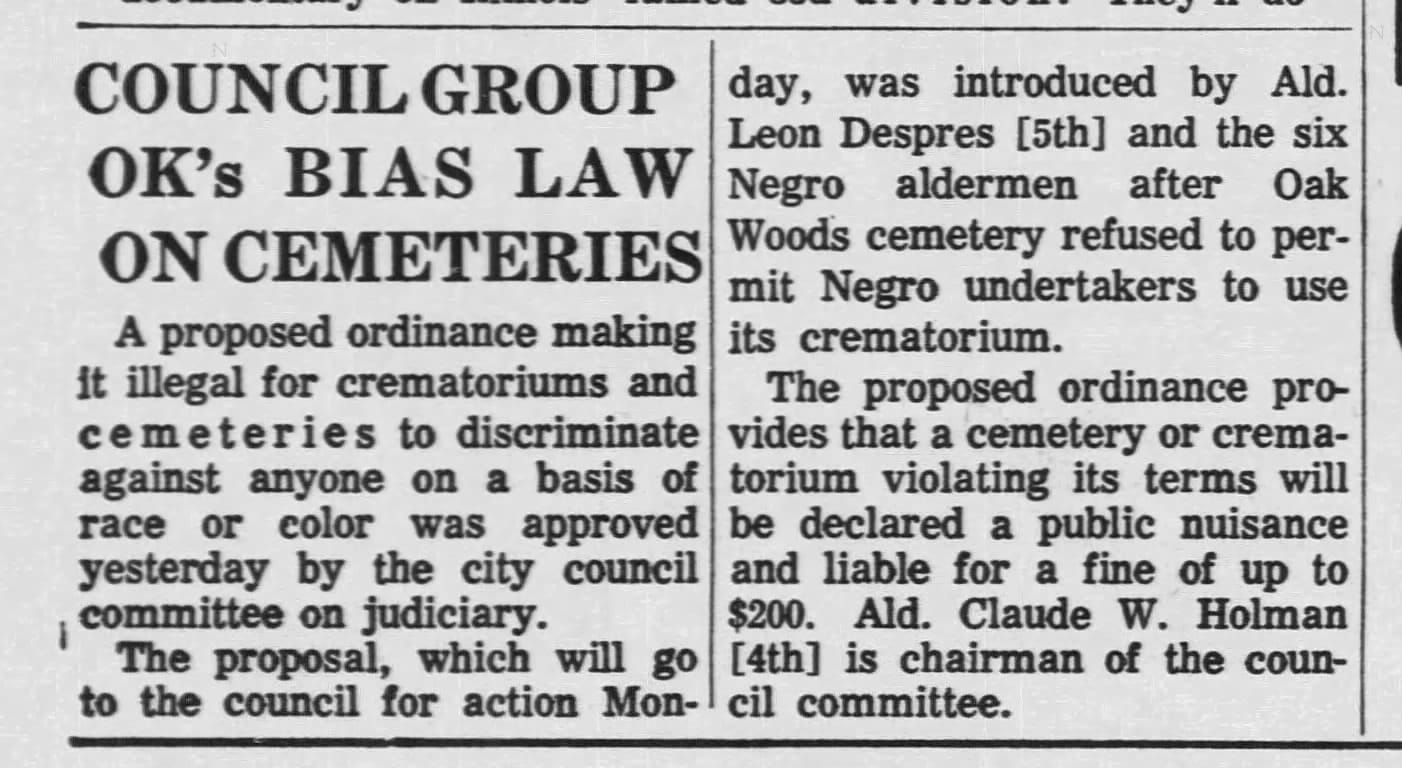

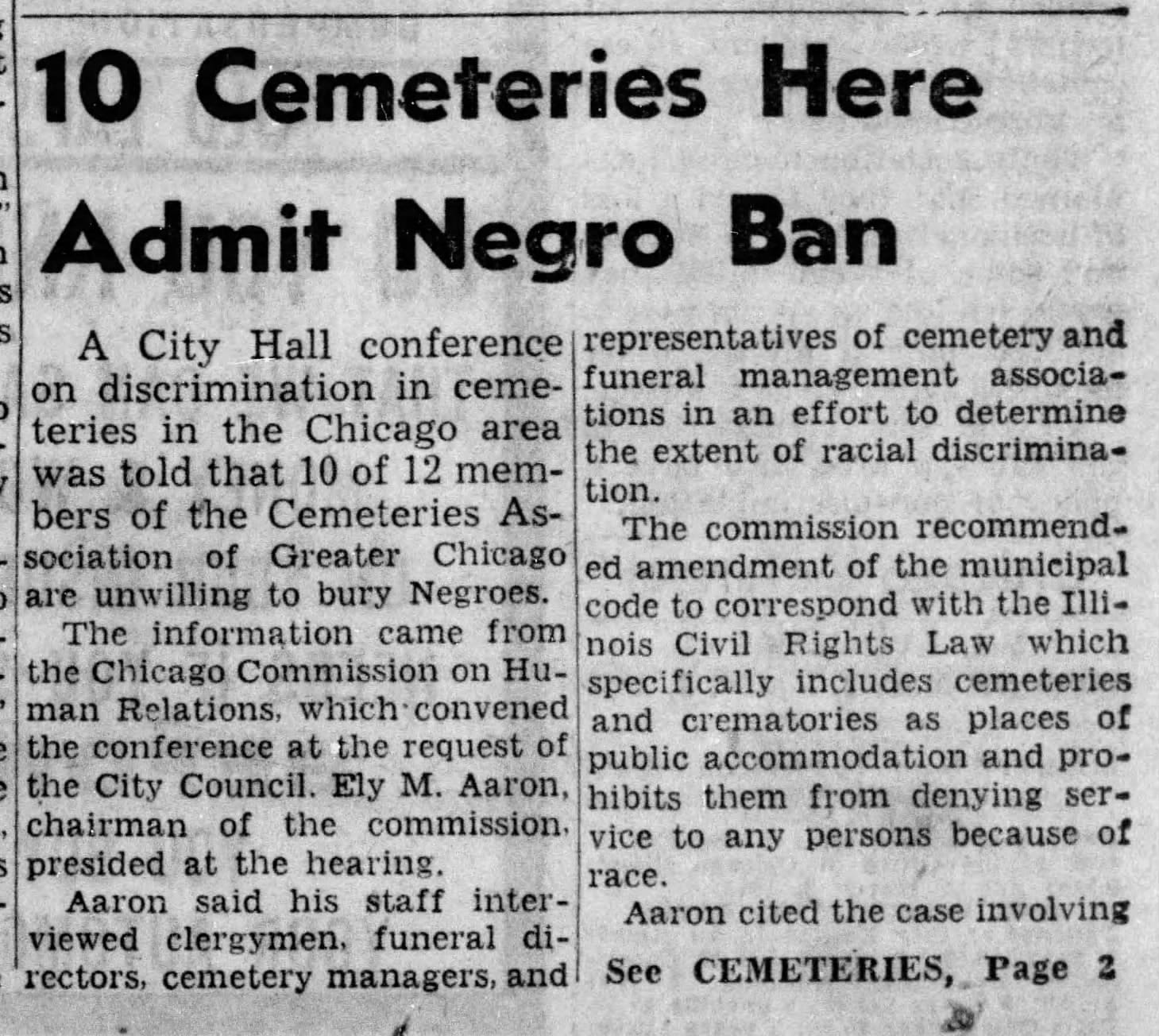

While Marshall Bynum forced Oak Woods Cemetery into increasingly embarrassing public positions to maintain its color barrier, the NAACP, faith leaders, and the funeral industry also pushed legislative change. Finally, in 1959, the Illinois state legislature passed a law outlawing racial discrimination in cemeteries.

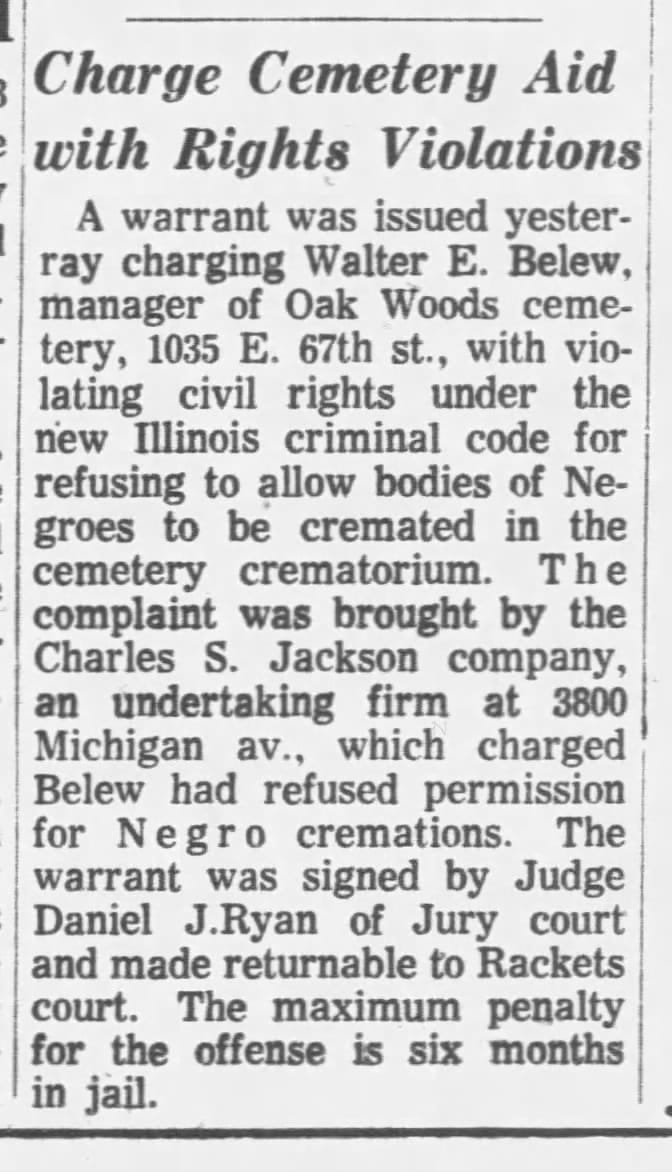

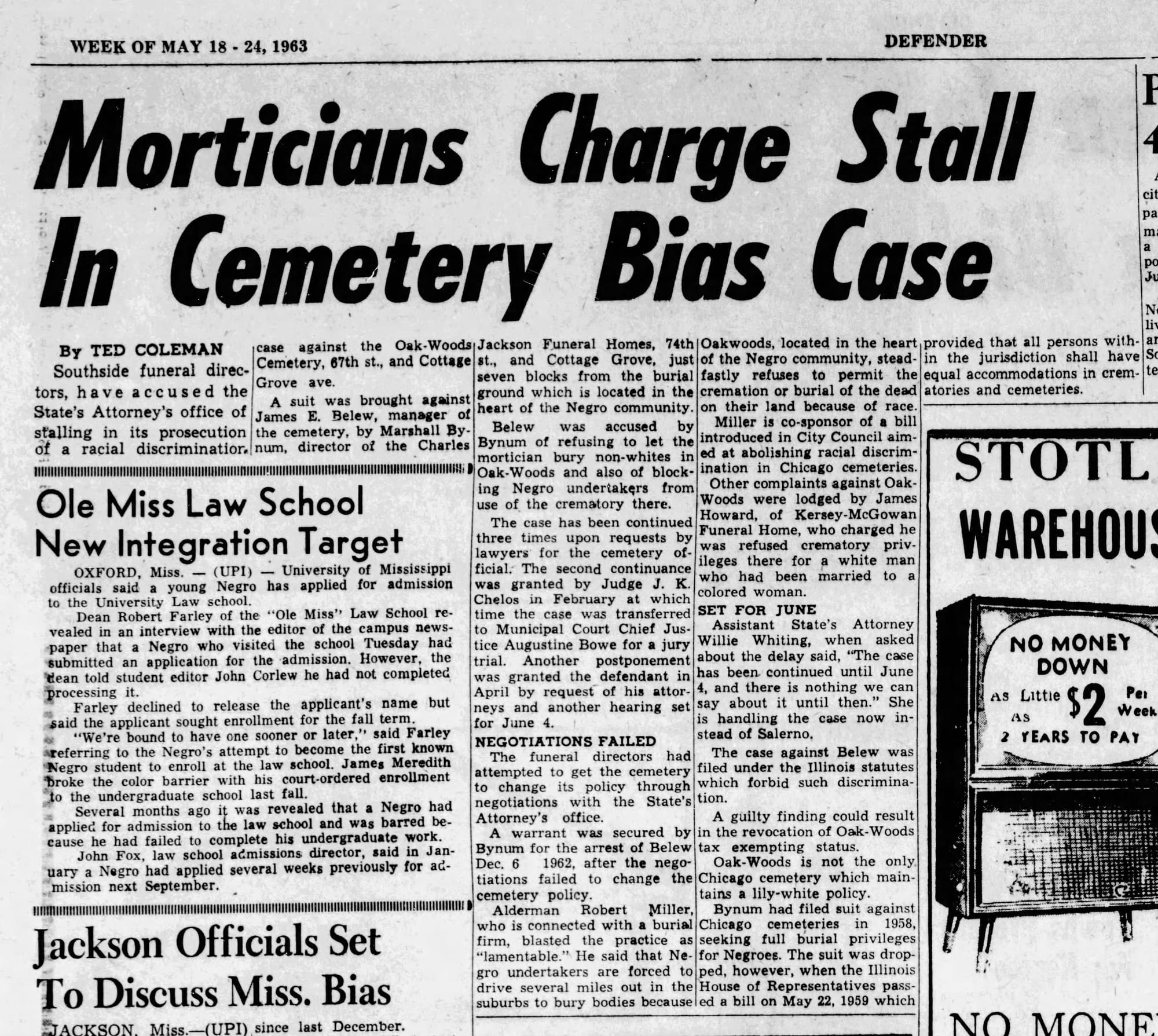

1962, "Charge Cemetery with Civil Rights Violations", Chicago Tribune | 1963, Chicago City Council outlaws racial bias in cemeteries, Chicago Tribune | 1963, state stalling on Oak Woods discrimination case, Chicago Defender| 1963, Admit Ban, Chicago Defender | 1963 articles on the protest in the Chicago Defender and Chicago Tribune

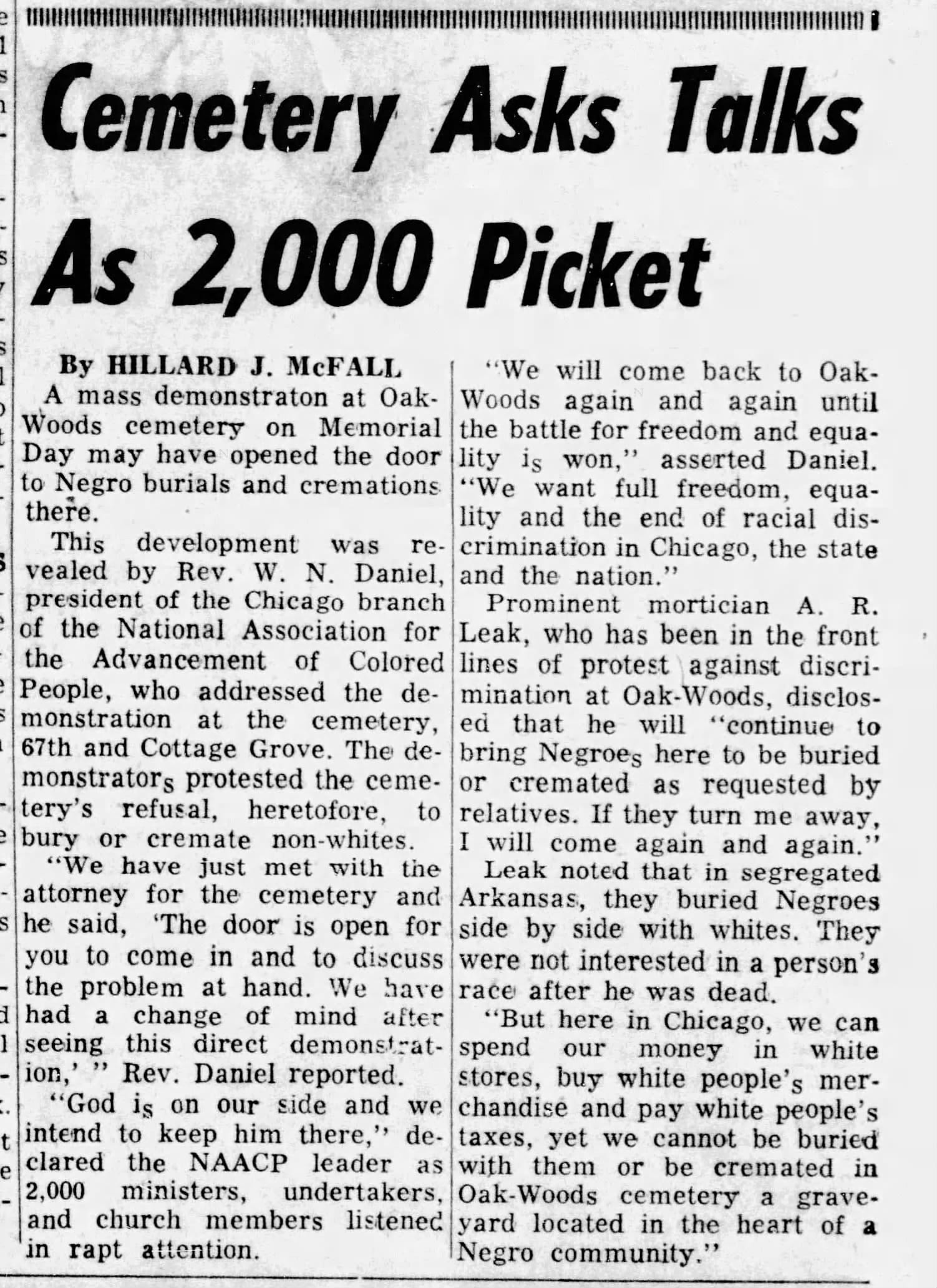

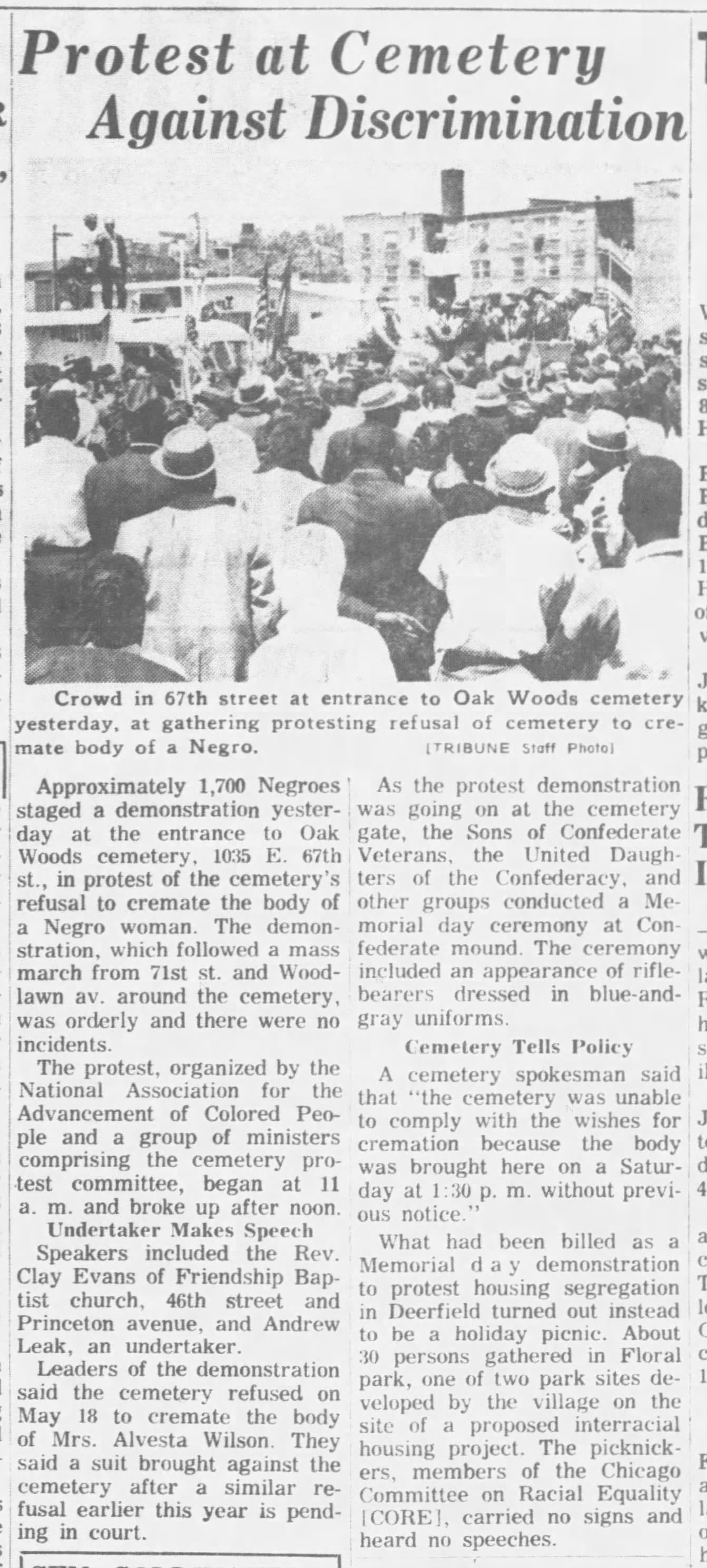

…and Oak Woods continued to refuse to cremate or bury Black people, with Oak Woods manager W.E. Belew maintaining the cemetery’s white-only policy. Already a facing a lawsuit for violating the state civil rights law, in May 1963, the cemetery once again refused to cremate the body of Black person—Mrs. Alvesta Wilson—and funeral director A.R. Leak joined with Rev. W.N. Daniel and Rev. Clay Evans to organize an NAACP-supported demonstration outside the cemetery gates, drawing thousands.

Oak Woods’ management was clearly deeply committed to their racism, but they also presumably needed to make money, and the neighborhood around the cemetery had changed immensely since they instituted the color line. Between 1950 and 1960, Greater Grand Crossing went from 6% Black to 86% Black. Pressured by protests and lawsuits, and faced with a serious commercial problem as their chosen customer base white fled, Oak Woods Cemetery finally integrated in 1963.

However, the Black community—understandably—didn’t immediately rush to bury their loved ones in the cemetery that had discriminated against them for decades. Chicago’s African American elite initially continued to patronize the suburban cemeteries who had been open to them all along—but Oak Woods was convenient and Oak Woods is beautiful.

2025

Things started to change in the 1980s—Olympian Jesse Owens was buried here in 1980—but it was the burial of Chicago Mayor Harold Washington that truly restored Oak Woods’ position as the South Side’s prestige cemetery. Mayor Washington died unexpectedly, early in his second term, with no burial plans—Chicagoland’s cemeteries knew that landing the resting place of the city’s first Black mayor would be a coup, so they competed for the honor. Oak Woods gifted the Washington family a large plot on a prime piece of land, and Mayor Washington was interred at Oak Woods on November 30th, 1987. It wasn’t even 25 years after Oak Woods' color line had fallen and cemetery management was falling over themselves to honor a Black politician—a small, belated victory, I guess.

Production Files

Further reading:

- "New Modern Crematory in Chicago" in Park and Cemetery in April, 1910

- "Perfecting Details of Crematory Service" in Park and Cemetery, 1911

- 1955 history from Oak Woods

Marshall F. Bynum seems like a very impressive guy—besides fighting Oak Woods Cemetery management, running a funeral home, and helping lead the Chicago branch of the NAACP, he was also the first Black man on Board of Commissioners of the Chicago Parks District.

1950s and 1960s articles on Bynum, mostly in the Chicago Defender, but with the park district board photo and obituary from the Chicago Tribune

Both Bynum and A.R. Leak also had practical reasons to want to desegregate Oak Woods—it was the closed cemetery and crematorium to their funeral homes by far.

Some other William Carbys Zimmerman buildings.

This is where I took the photo from.

Member discussion: