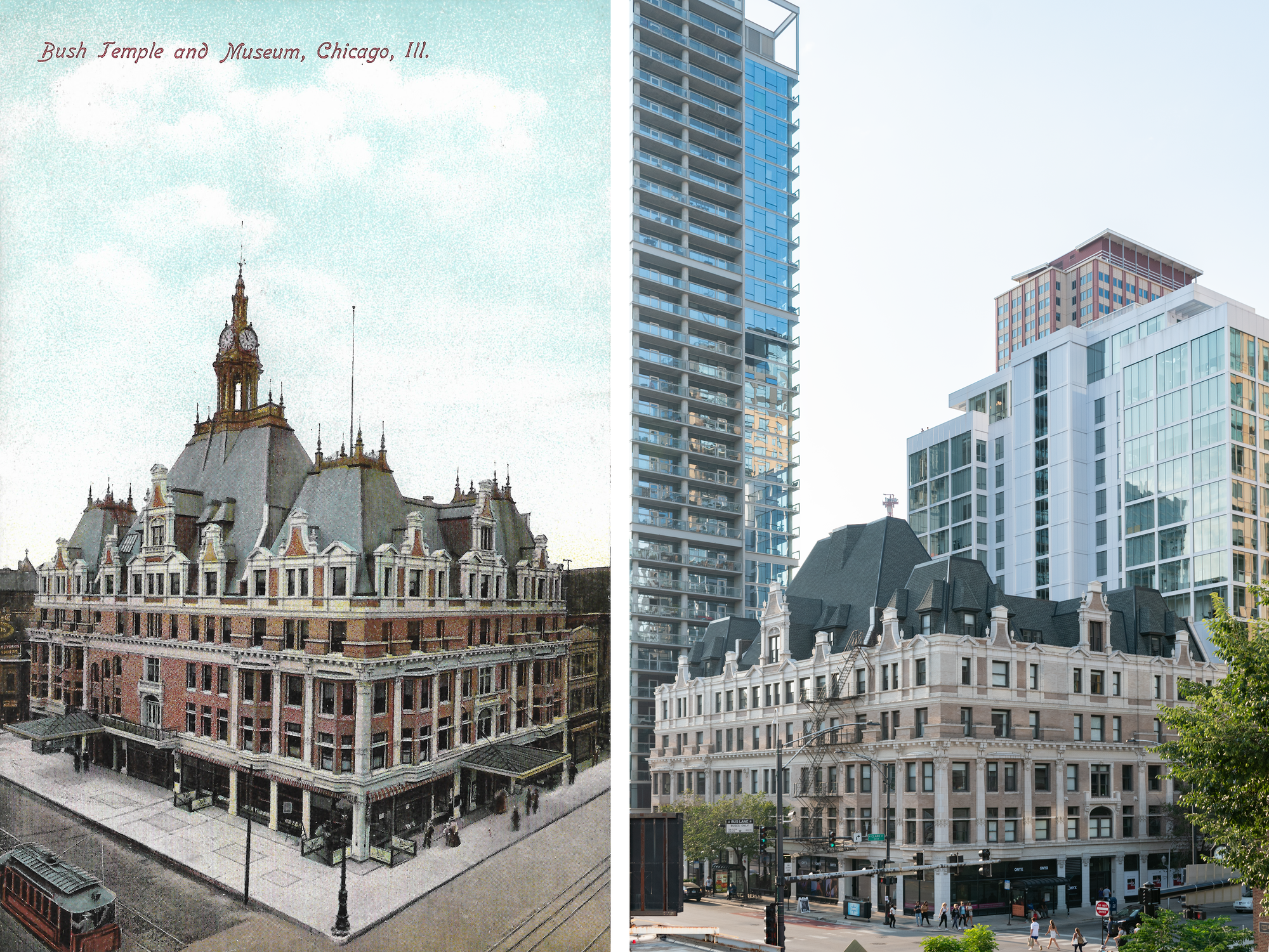

For all its Châteauesque grandeur–and as Chicago’s only French Renaissance Revival commercial building, it’s certainly grand–the initial version of the Bush Temple of Music was…kind of a failure? The piano company that built it–Bush & Gerts–moved out after only a decade, and the auditorium, studio space, and recital halls they hoped would drive demand for their pianos were demolished only twenty years after the building opened in 1902. For nearly a century, this extravagant exterior contained very ordinary offices, until the building was converted into apartments in 2017–it seems likely that this third iteration of the Bush Temple will be the most successful.

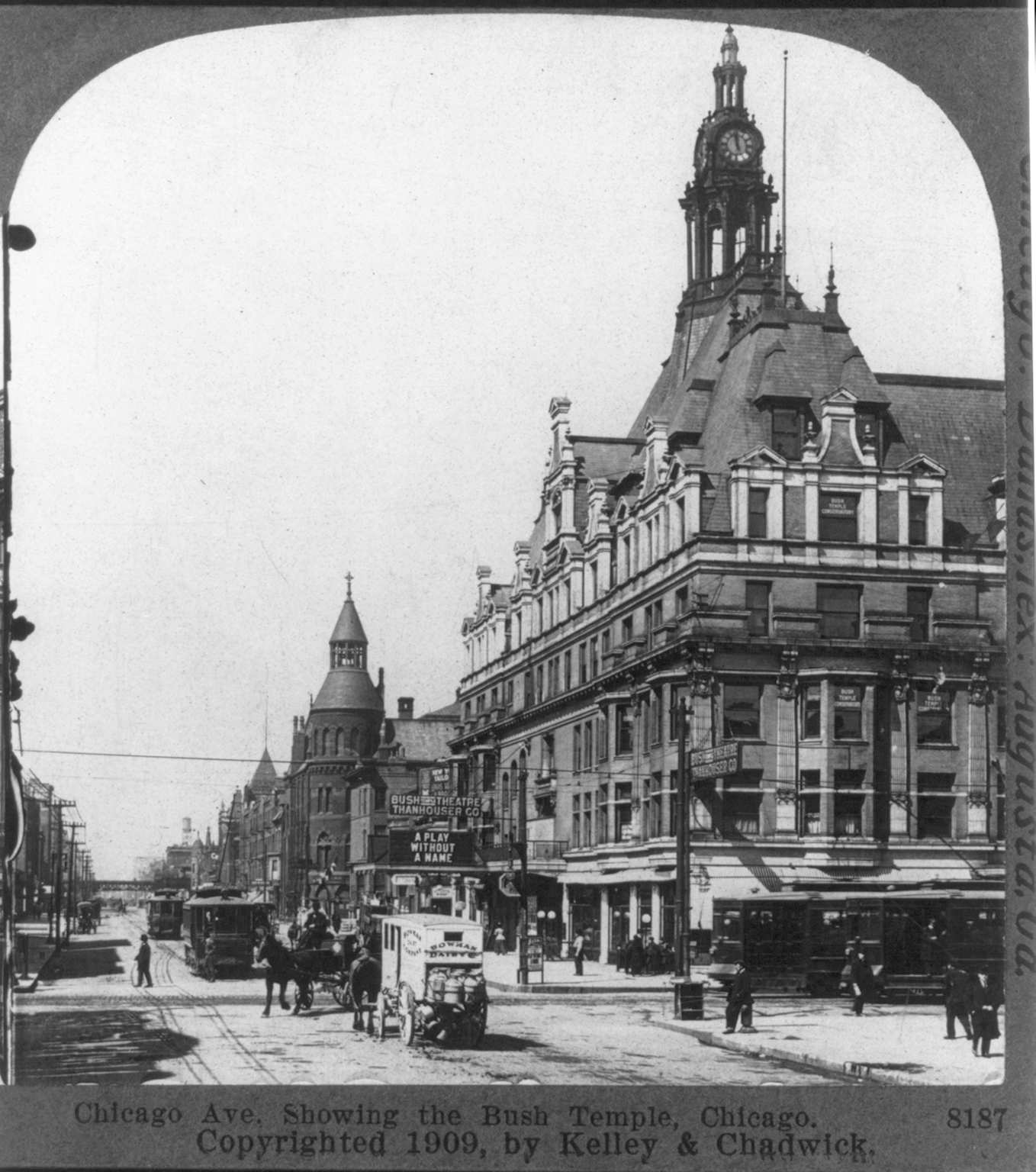

So what’s changed? The clocktower is the obvious thing, removed in 1922-1923 when the building was converted to offices. That renovation also removed the tiny second floor balcony on the Chicago Avenue elevation, got rid of the canopies over the entrances, and filled in the roof line on the fifth floor to bring it flush with the dormers. A bit of ornament has been lost here and there and some new windows have been added on the top floors, but otherwise the exterior is remarkably intact. The other big change is the streetcar–the last Chicago Avenue streetcar rattled the windows of the Bush Temple in 1952, when they were scrapped for buses. Oh, and I have no idea why the postcard says, "and Museum". Clearly a mistake on the postcard publisher's part, there was never a museum here.

The Bush & Gerts piano company, founded by William Bush, William Bush, and John Gerts, carved out a market manufacturing midrange pianos during absolute peak piano– in 1905 there were more pianos and organs in the US than bathtubs. William H. Bush, the big Bush, was a wealthy lumber baron, but his son, William L., didn’t want to join the family business. William L. Bush successfully convinced daddy to finance a piano company, and they partnered with John Gerts, a German immigrant who actually knew how to make pianos.

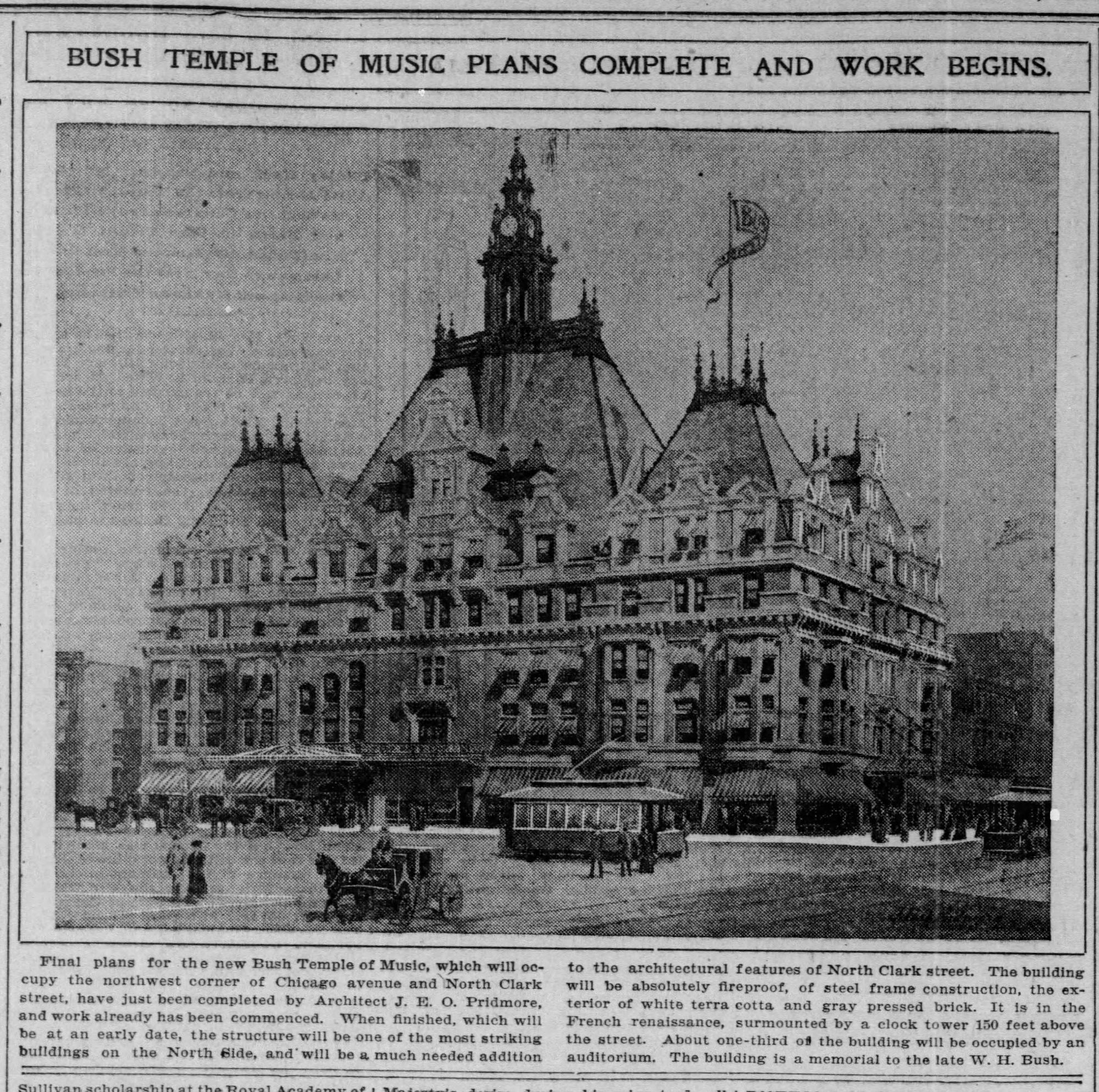

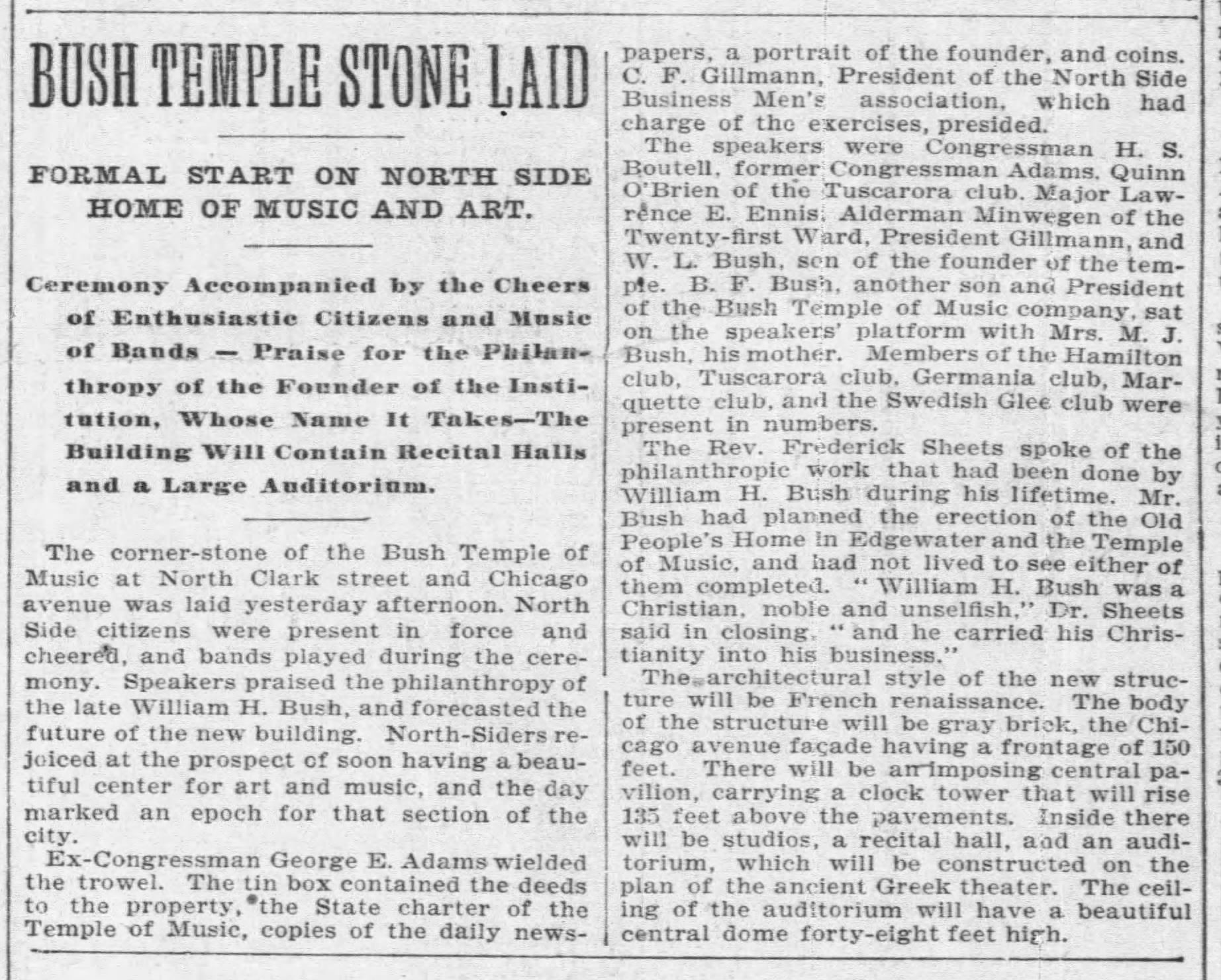

1901 articles on the plans for the building and its cornerstone laying | photo in the Inland Architect in 1902 | 1902 ad for the Bush & Gerts company | Ads in The Diapason (a journal for professional organists) for the music-related businesses that also occupied the building

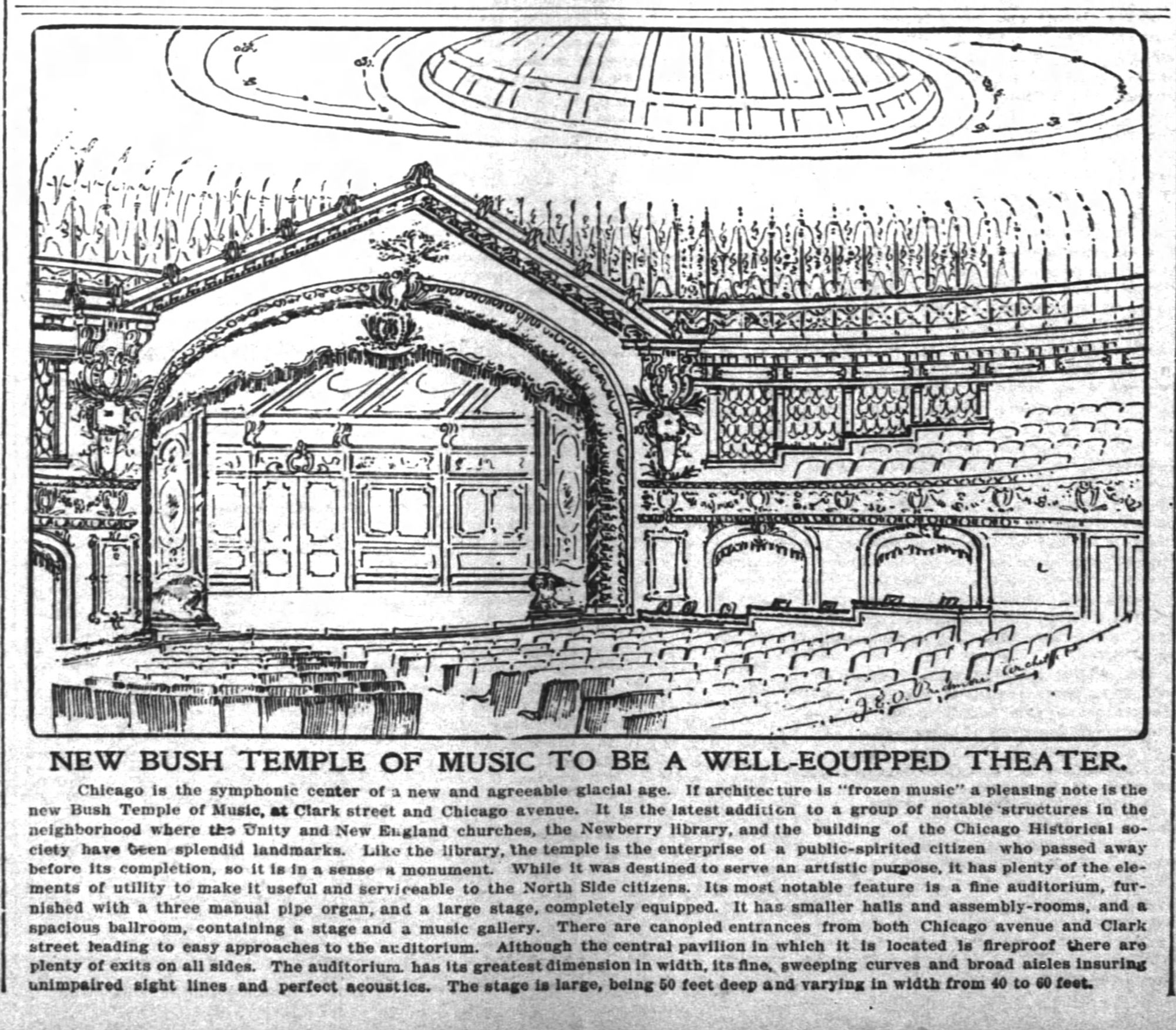

The company manufactured their pianos from a factory at Dayton St. & Weed St., but the Bushes aspired to something grander. They envisioned an extravagant piano showroom and office that would serve as an advertisement for Bush & Gerts pianos both inside and out. To stoke demand for their pianos, the building would also contain a conservatory to teach music, recital halls and studios to practice, and an auditorium for performances, as well as space for businesses providing complementary services and expertise–they meant the temple of music thing literally. To design their temple, they hired architect J.E.O. Pridmore.

The Manor House Apartments, Edgewater, the V. O. Hammon Collection, the Newberry Library | the Manor Apartments, Newberry Library via Chicago Collections | The Stickney School, 2016, Google Streetview | The Beaconsfield Apartments, 2015, Google Streetview,

This was Pridmore’s big break. In his early 30s and back out on his own after leaving a partnership with architect Leon Stanhope in 1899, the Bush Temple of Music set the tone for the rest of Pridmore’s career. Working on the Bush Temple of Music, Pridmore got really into theater design, and he spent the rest of his career designing theaters and luxury apartment buildings in opulent historic revival styles, mostly on Chicago’s North Side (Pridmore was a longtime Edgewater resident). Pridmore-designed buildings that still stand in Chicago include the Preston Bradley Center, the Manor House Apartments in Edgewater, the Beaconsfield-Hollywood Apartments, and the Stickney School (all his Chicago theaters have been demolished [the Vic Theatre on Sheffield is often misattributed to him]).

2023 photo, me | 2013 photo of the window details, Susan Baldwin Burian, NRHP registration form | 1905, Chicago History Museum, ICHi-074026 | 1909 stereograph, Library of Congress | 1902 article on the building's opening

This is a unique example of the Châteauesque style in Chicago, and boy did they lean into it, with that bonkers high-pitched multiple hipped roof, the alternating pressed brick and white terracotta, just about every type of ornament you could name, and that absurd clocktower.

For all its stylistic bombast–E. Charles Hemming, the draftsman, must’ve had a field day–the Bush Temple of Music also needed to function as a mixed-use building. In its first decade, the building housed a piano showroom, an auditorium, three recital halls, artist and music studios, a photo studio, a barbershop, a banquet hall, a cafe, a florist, and offices–so like, extremely mixed-use. Besides the music industry, offices in the building were also popular with unions. The Plumbers, Gas Fitters, Steam Fitters, & Steam Fitters Helpers Union, the Bakery and Confectionery Workers Union, and the International Glove Workers Union all had their national offices in the building in its first decade.

Again, though–Bush & Gerts opened their Temple of Music at peak piano, and it didn’t really work out (...and perhaps a temple wasn’t the right fit for a company focused on the midrange piano market?). After only ten years, the company moved their offices and showroom back to their factory. The Bush Conservatory of Music and Dramatic Art, intended to educate the next generation of stars (who’d use Bush & Gerts pianos) and which employed famous pianists including Fannie Bloomfield Zeisler, Julie Rivé-King, and Harold von Mickwitz as instructors, moved out in 1918. While the Bushes and their would-be piano empire had effectively disappeared, the auditorium remained a lively venue for meetings, musical performances, and theater–it was the home of Chicago’s German Theater company, amongst others.

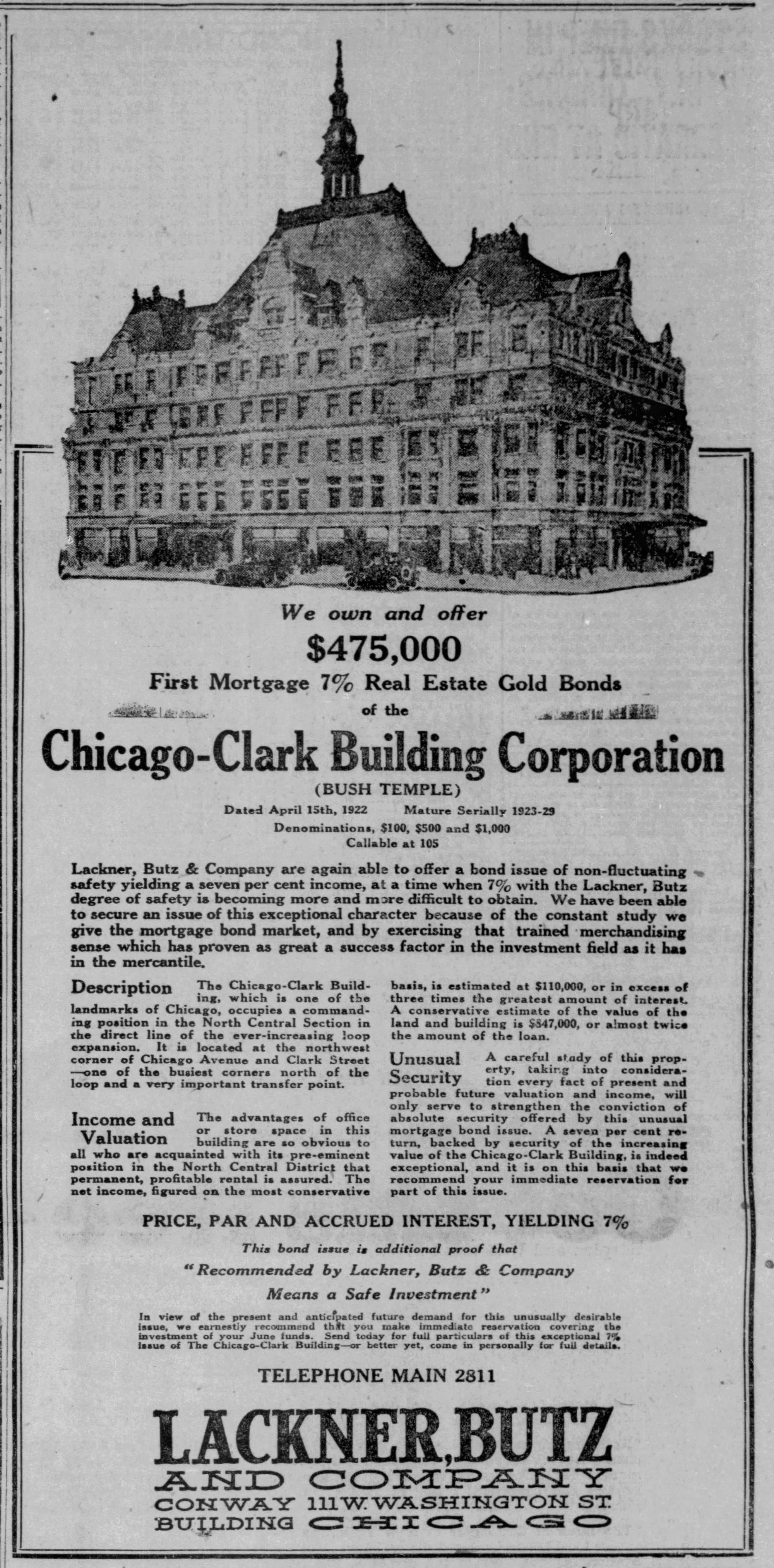

1902 ad for the Bush Conservatory | 1902 depiction of the auditorium in the building | 1919 German-language ad in the Abendpost, the Internet Archive | 19`2 classifieds about Bush & Gerts moving their showroom back to their factory and putting their space in the Bush Temple up for lease | 1922 article about the building sale and an advertisement for the bond sale to finance the conversion to offices

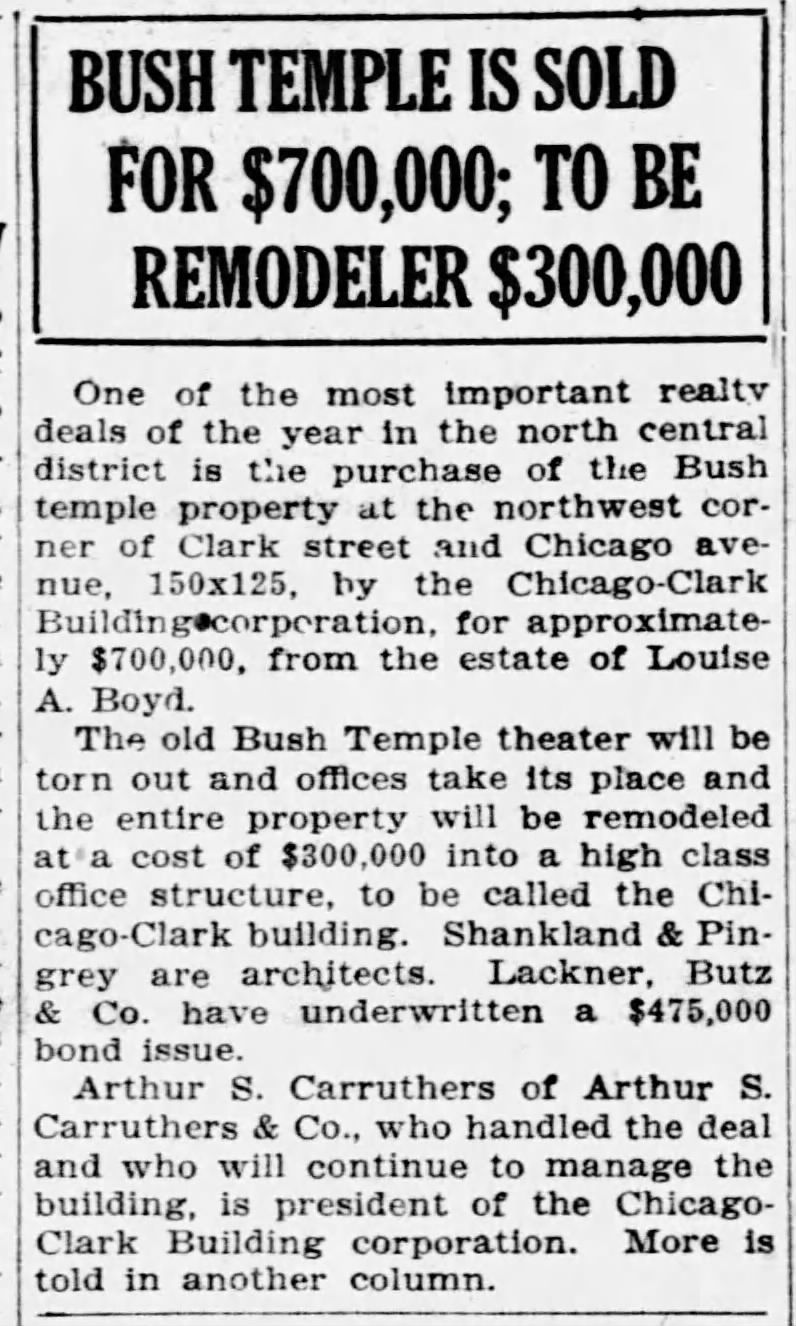

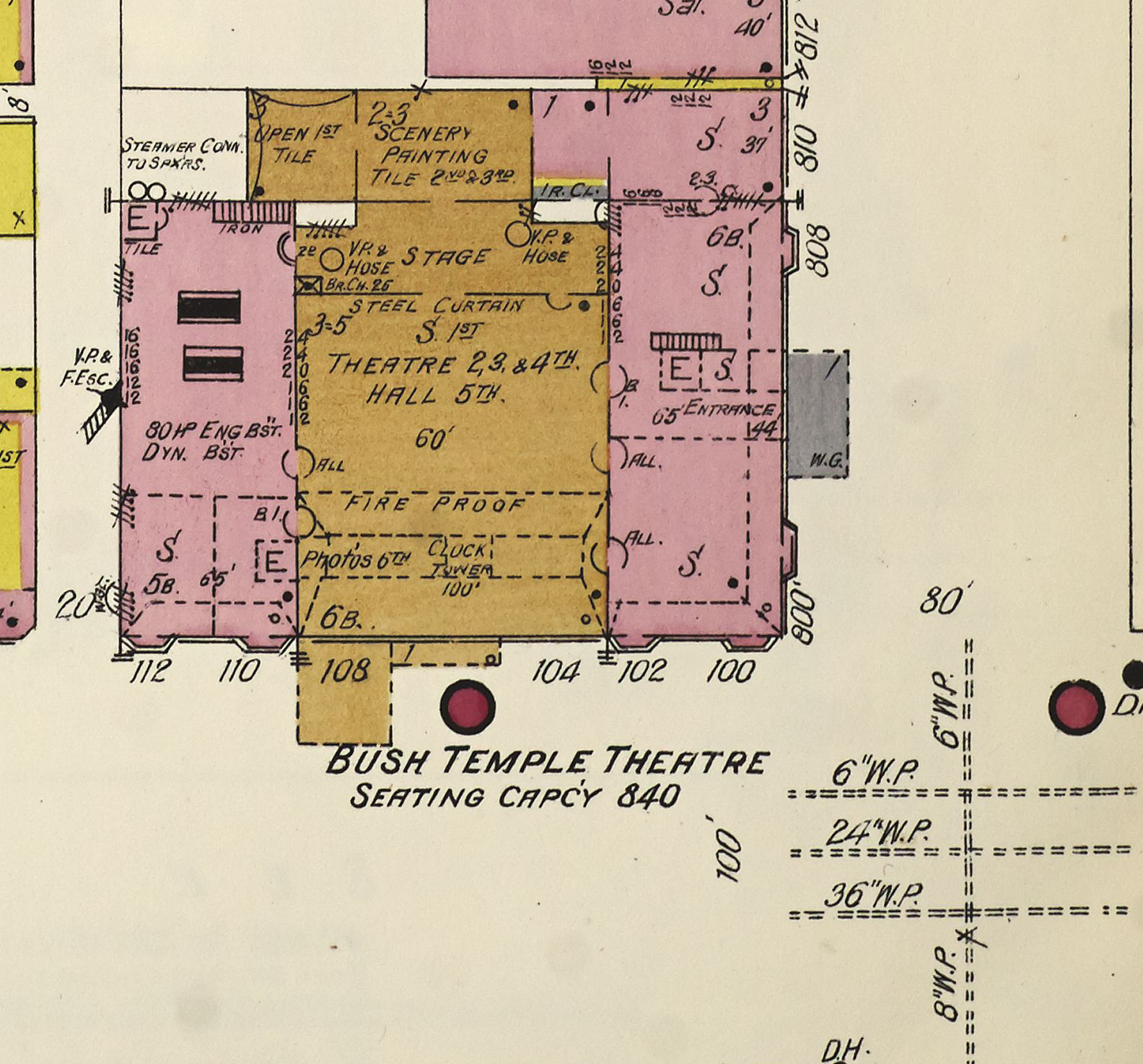

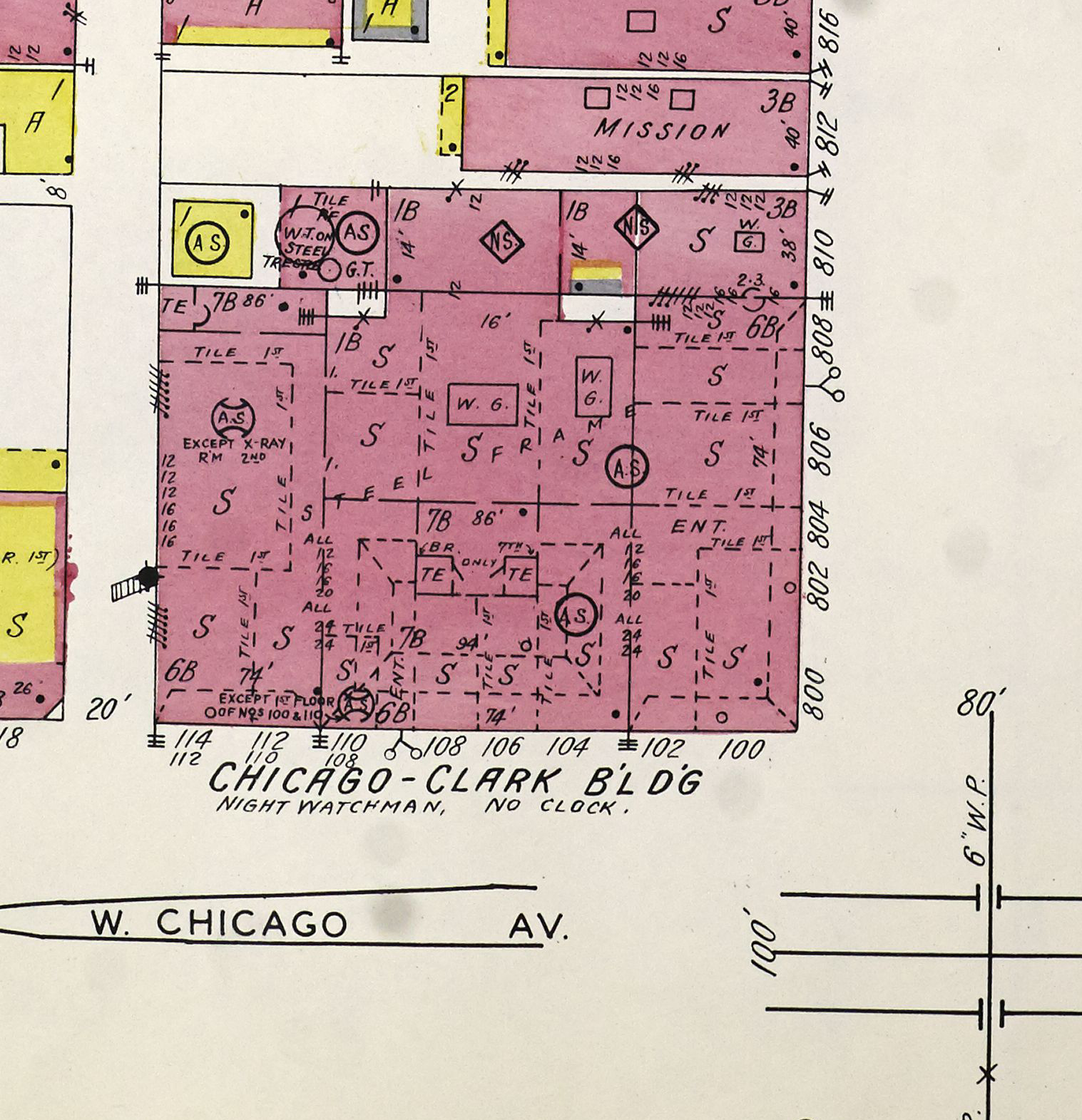

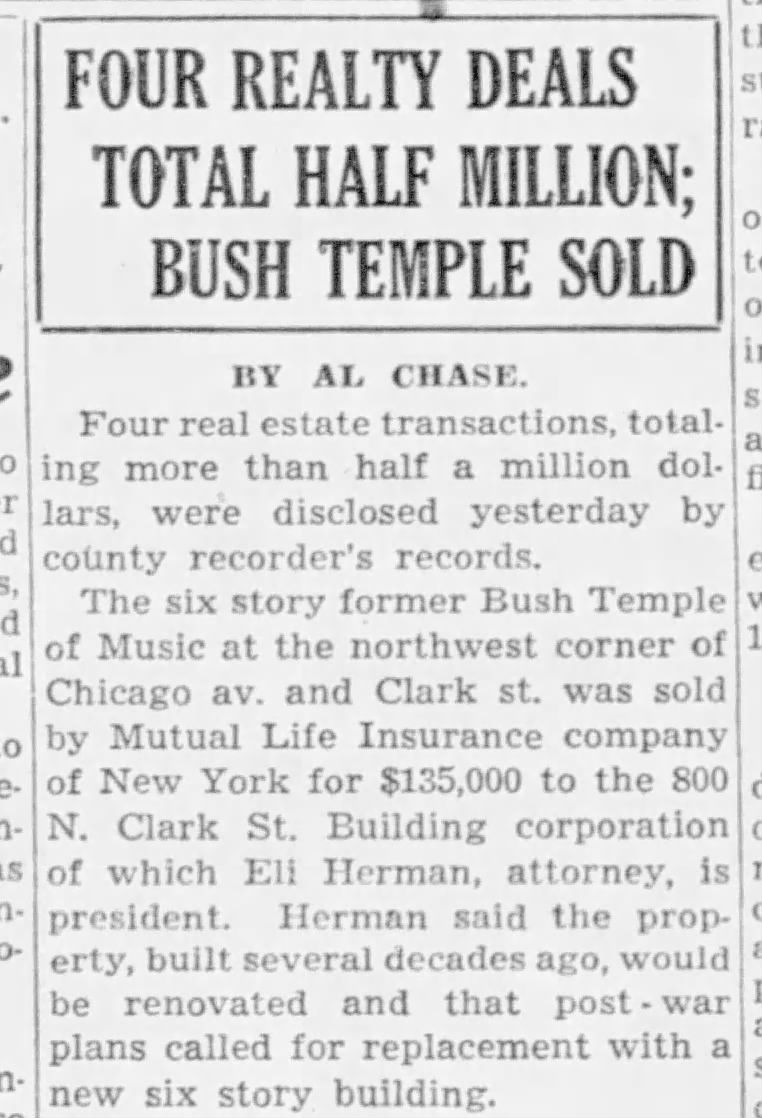

However, German plays weren’t enough to keep the lights on, and the Bush Temple was sold in 1922 to owners who converted the whole thing into offices. With Shankland & Pingrey the architects for the renovation, the clocktower, the auditorium and the recital spaces were razed and new office floors built out–the changes between the 1910 Sanborn map and the 1935 version really tell the story. Renamed the Chicago-Clark Building, a procession of publishers and journals, religious stuff (the Moody Bible Institute is nearby), lawyers, doctors, and dentists passed through the building over the next few decades.

1910 Sanborn map vs. 1935 Sanborn map

A new owner in the 1940s stated his intention to demolish and replace the Bush Temple, but it looks those plans never went anywhere. In the 1960s and 1970s civic and social organizations moved into the building: the City of Chicago rented office space here for their HR department, Chicago Public Schools operated a satellite location of Waller High School here (present-day Lincoln Park High), and it was the home of the Near North Center of the Chicago Committee on Urban Opportunity.

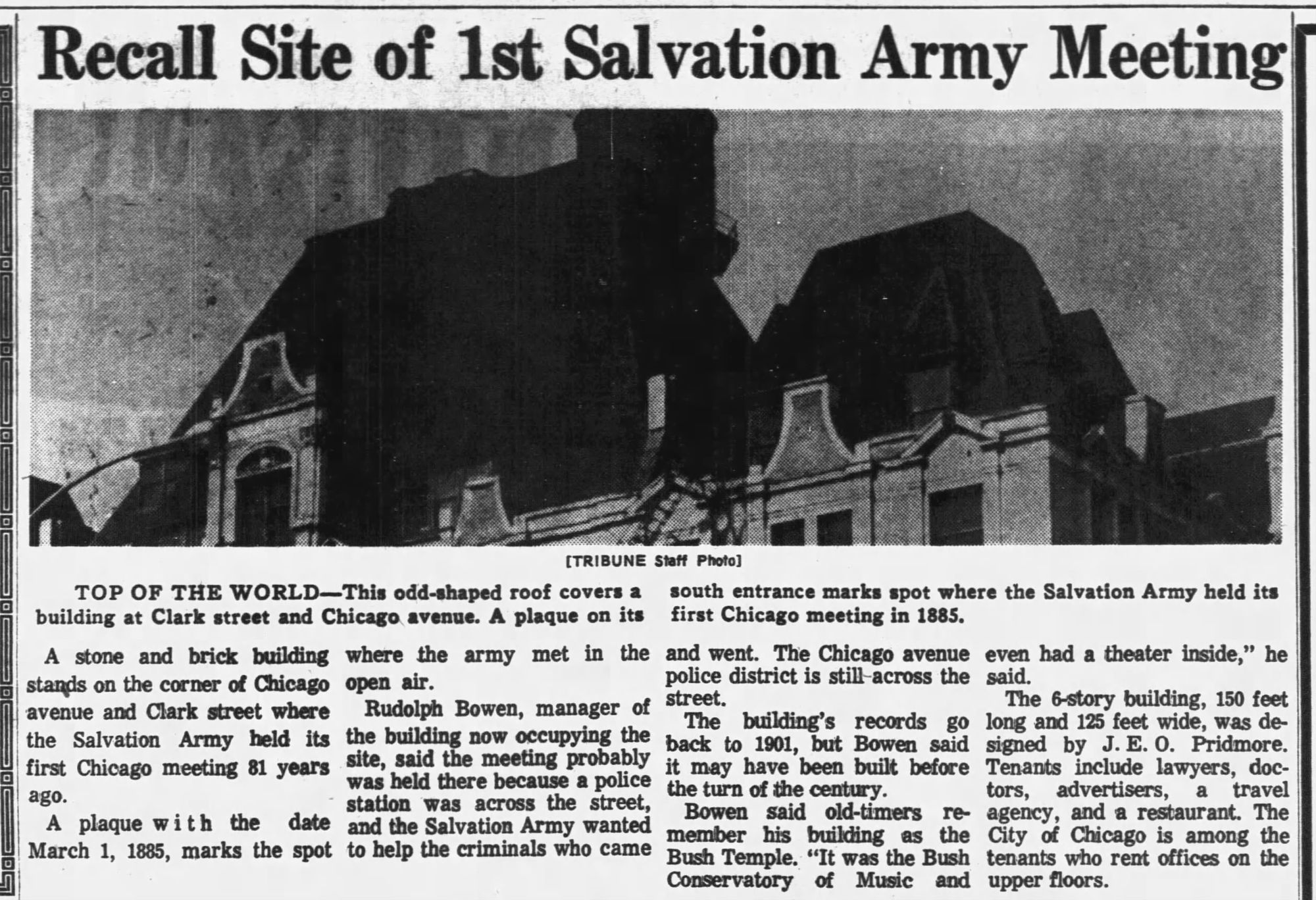

Article on the building's sale in 1945 | 1966 article recalling how the first meeting of the Salvation Army in Chicago happened at this site | 1970s photo, Illinois State Historic Preservation Office | 1970 article on the Waller High School satellite that operated in the building | 1976 photos, C. William Brubaker, UIC Library via Chicago Collections | 1980s photos, John P Keating Jr | 2013 photo, Susan Baldwin Burian, NRHP registration form

A Chicago landmark designation in 2001 prevented demolition, but the aging office space continued to slide downmarket and by the 2000s the building was mostly vacant. A 2013 listing on the National Register of Historic Places made it eligible for federal tax credits. Purchased by Cedar Street Companies, in 2015 the developer leveraged the Federal Historic Tax Credit and the Adopt-a-Landmark incentive to finance the building’s restoration and conversion into apartments. Hartshorne Plunkard designed the apartment conversion, which opened in 2017, part of a two-stage development that also included the construction of the white apartment tower to the north (they share a lobby).

Pridmore’s building is a delightful confection on the outside, but the Bush Temple has been weirdly unsuccessful for a building that's survived 120 years–feels this version will finally break that streak.

2023 photos, me

Production Files

Further reading:

- The Chicago Landmark Designation Report

- The National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

- The Edgewater Historical Society on J.E.O. Pridmore

- Chicagology on the Bush Temple of Music

- In the Inland Architect, 1902

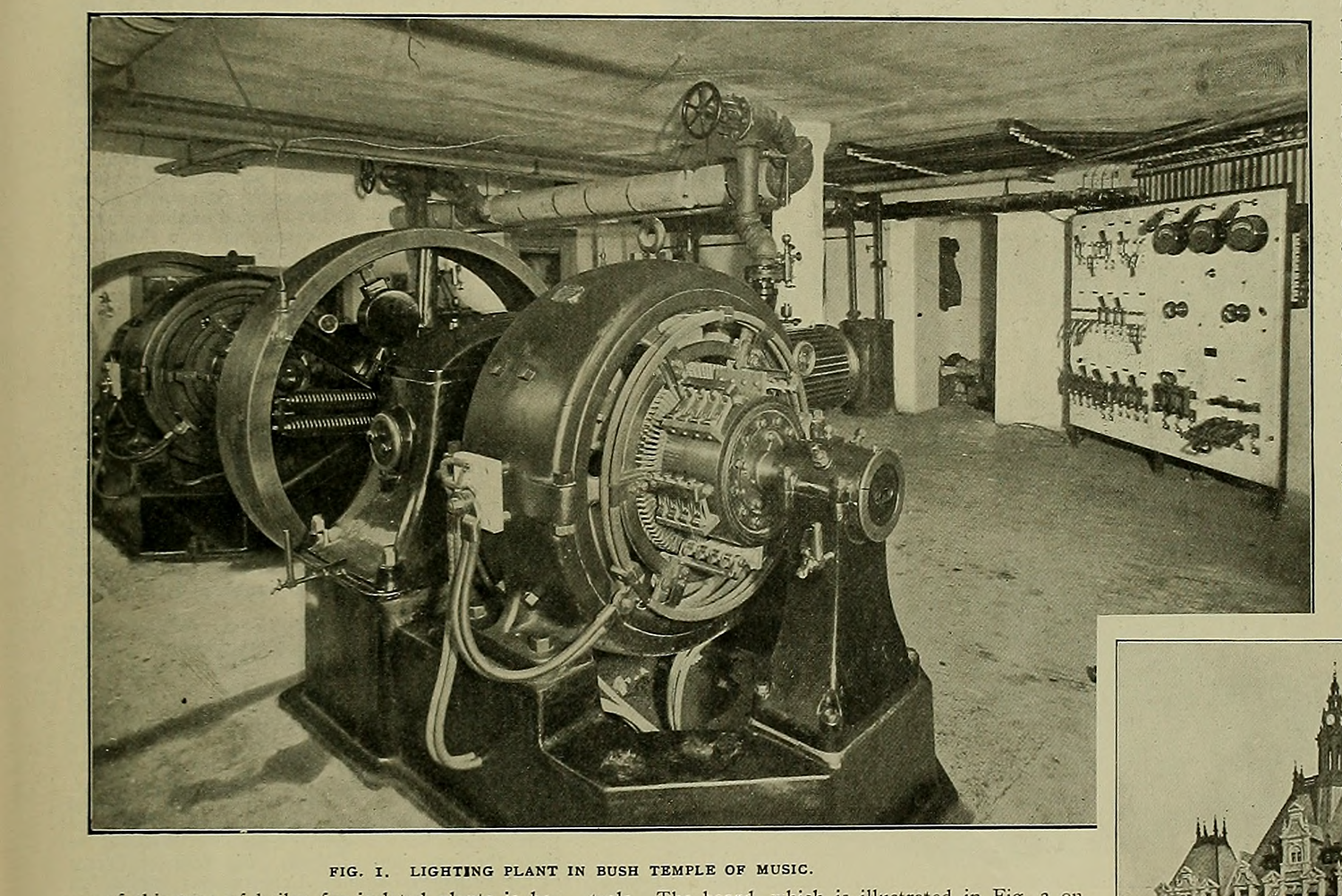

- Feature in Western Electrician on the lighting system in 1902

- In Chicago Design Slinger

- Various articles about the building pre-restoration, the restoration, and the reopening as apartments

There was an interesting labor conflict during the construction of the Bush Temple. The carpenter's union called for a boycott, because Bush the carpenters Bush hired were affiliated with a company union rather than an independent trade union. When Bush used non-union tile setters on the building's mosaics, the police stood guard.

More Susan Baldwin Burian photos from the 2013 NRHP registration form

A bunch of ads for businesses in the building

A 1909 ad for a theater performance in the building, with a play written by Wallace Rice, the designer of the Chicago flag | funny 1919 article about the painting of the spire | 1902 photo of the lighting plant in the basement of building in Western Electrician

Member discussion: