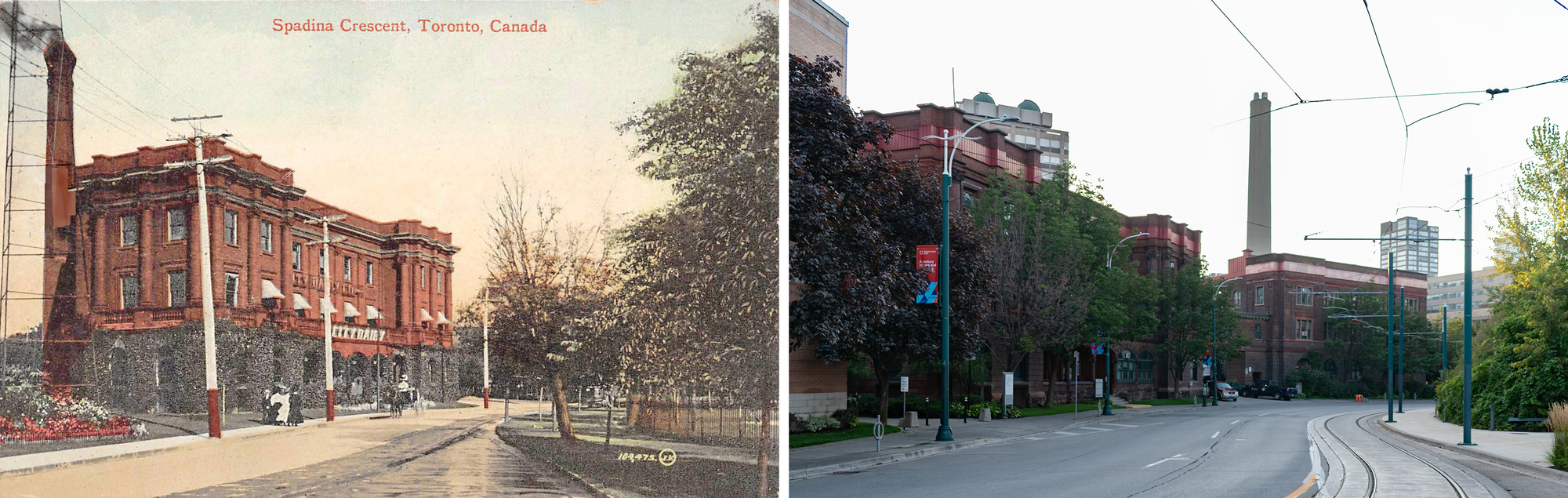

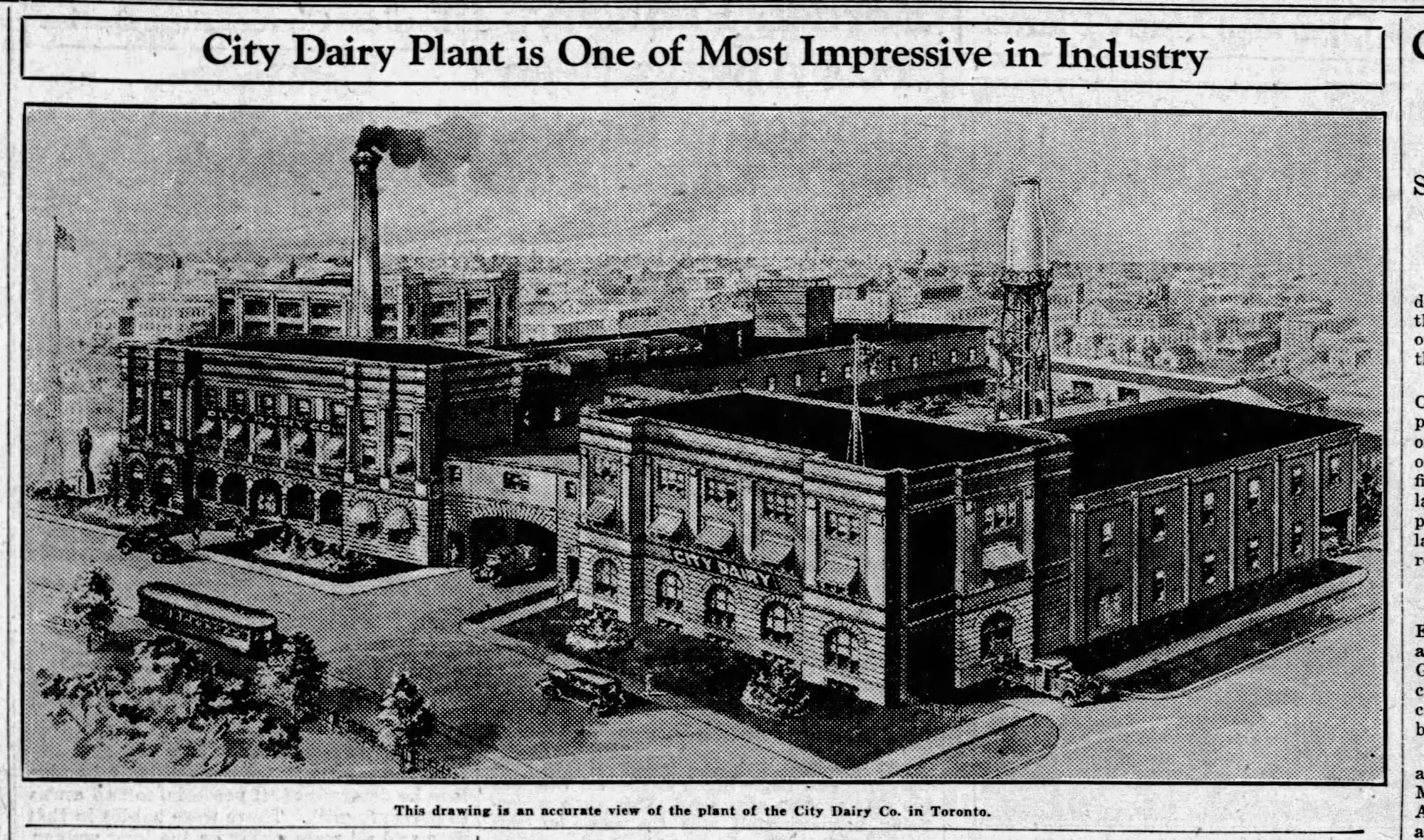

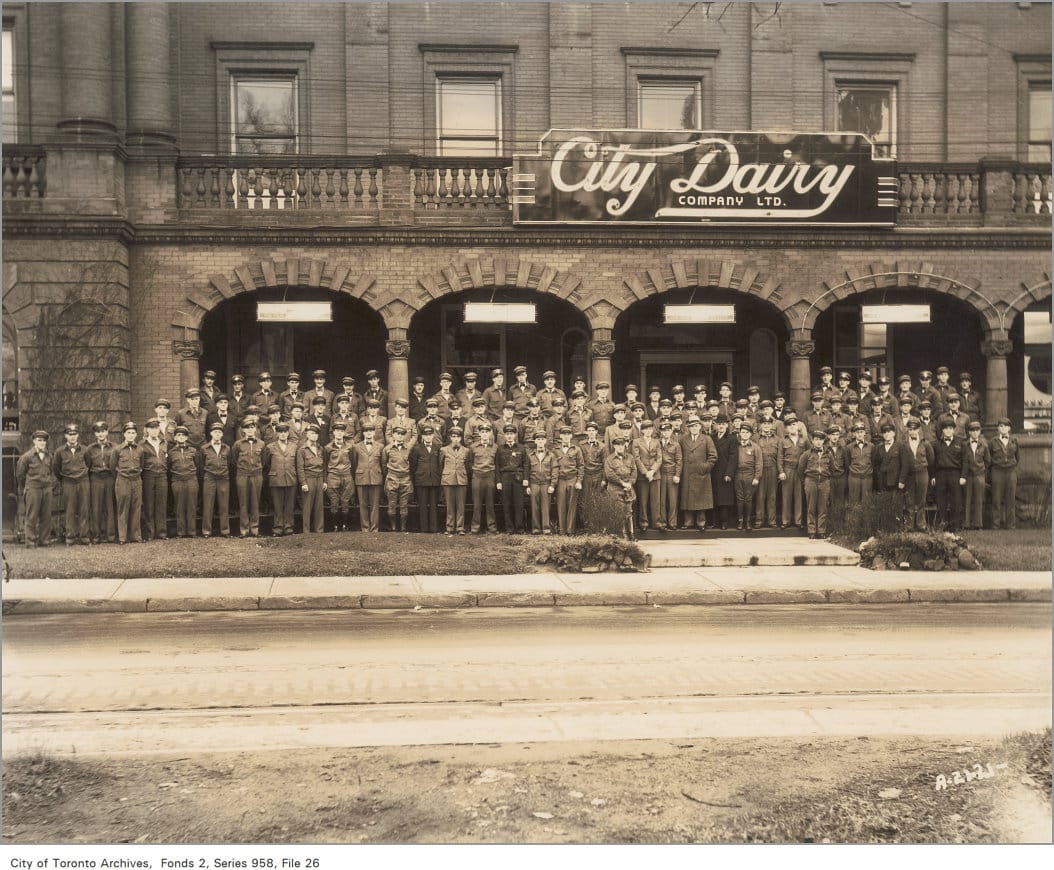

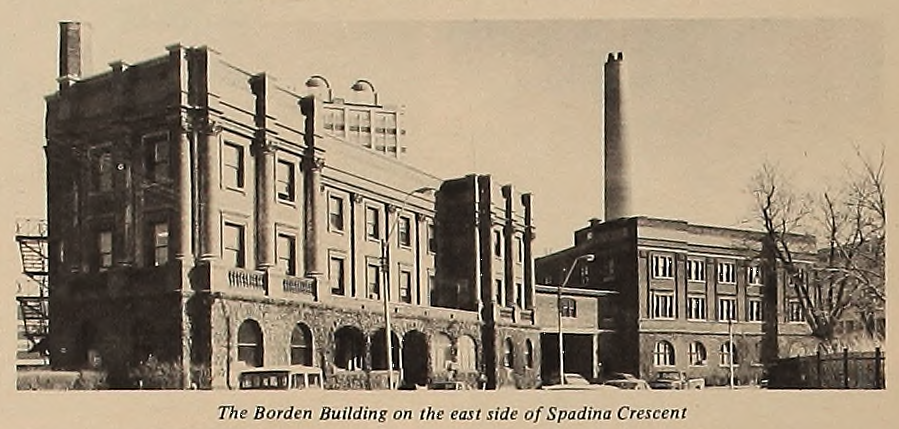

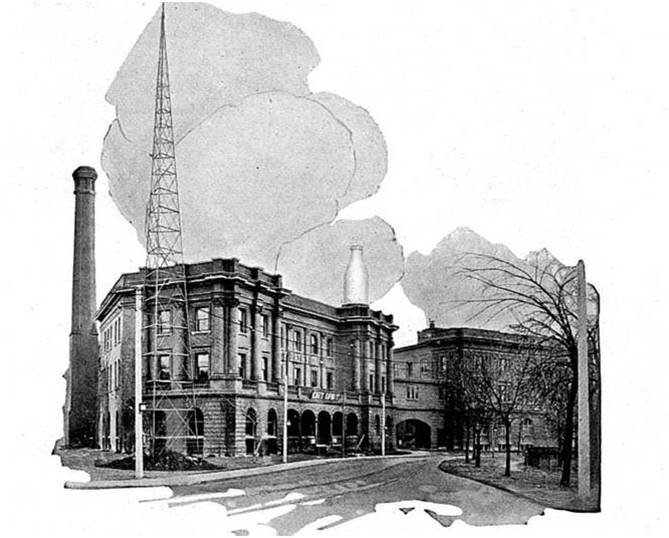

In a quirky and unusual example of adaptive reuse, the Borden Buildings on Toronto’s Spadina Crescent went from churning out butter, milk, and ice cream to churning out…sociologists, anthropologists, and foresters? Designed by architect George Martel Miller, the North Borden Building opened in 1901 as an industrial dairy processing plant for the City Dairy Company, one of the first Canadian adopters of milk pasteurization. From this complex the City Dairy Co. grew into one of the biggest dairies in Canada, with more than 40% of the Toronto milk market, before it was bought by the American dairy behemoth Borden in 1930. The University of Toronto St. George Campus swallowed up the Borden Buildings in the early 1960s.

In a sharp irony (and an example of triumphant resilience), where the Borden office here once participated in malnutrition experiments on indigenous kids in Canadian residential schools, today the North Borden Building houses U of T’s First Nations House and Centre for Indigenous Studies.

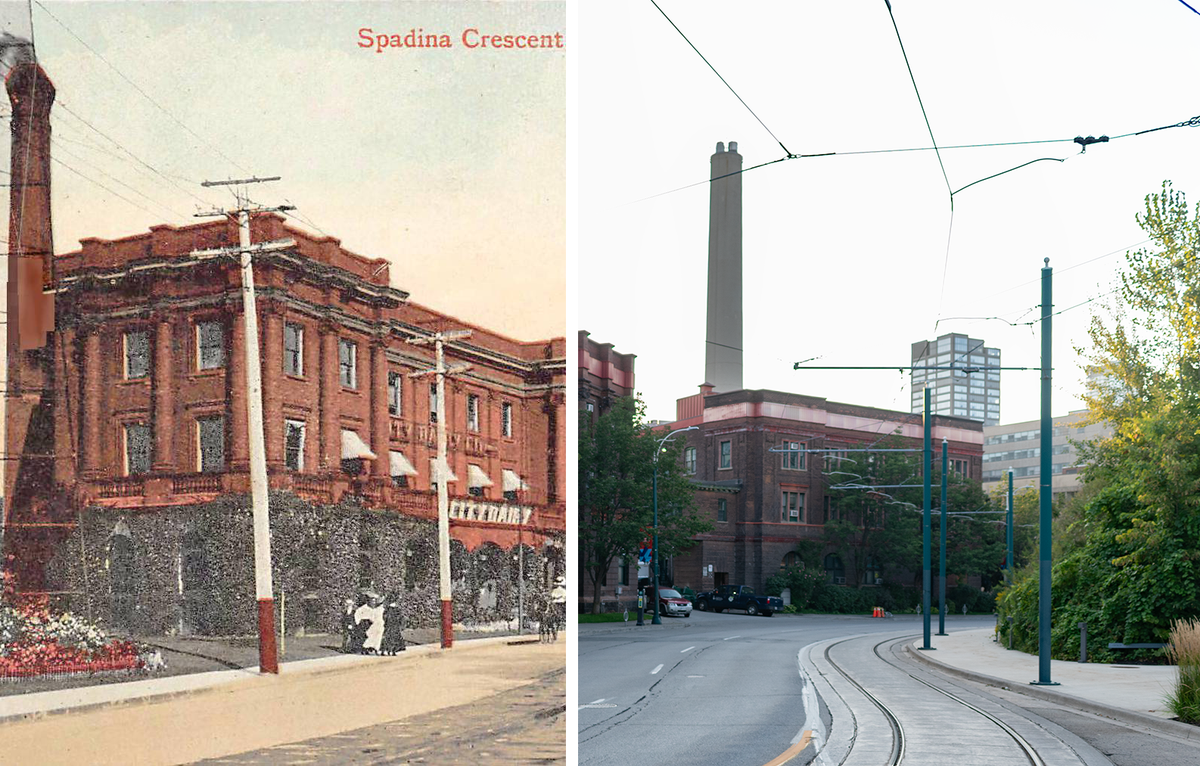

So, what’s changed?

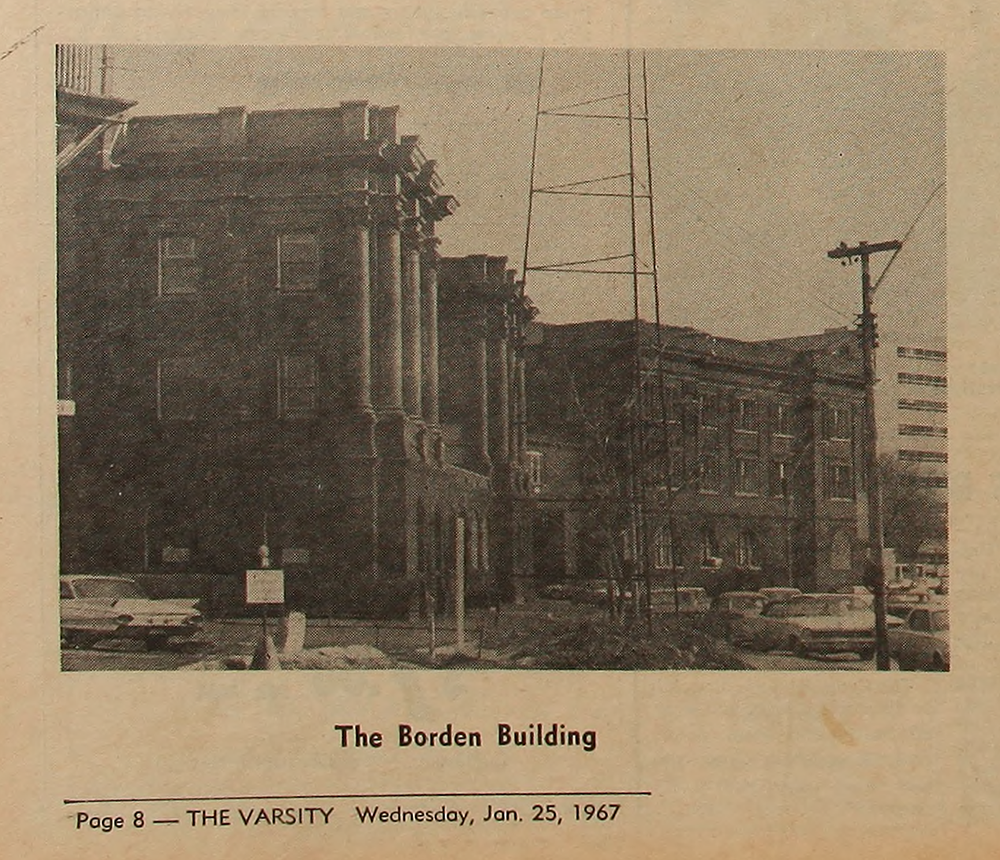

- The South Borden Building—where they manufactured ice cream, also designed by George Martel Miller—opened in 1910, and at some point they both lost their cornice, replaced by that shitty red metal band.

- The city widened Spadina Avenue (of course), chewing up some of the parkway in front of the Borden Buildings as well around the former Knox College building at the center of the circle.

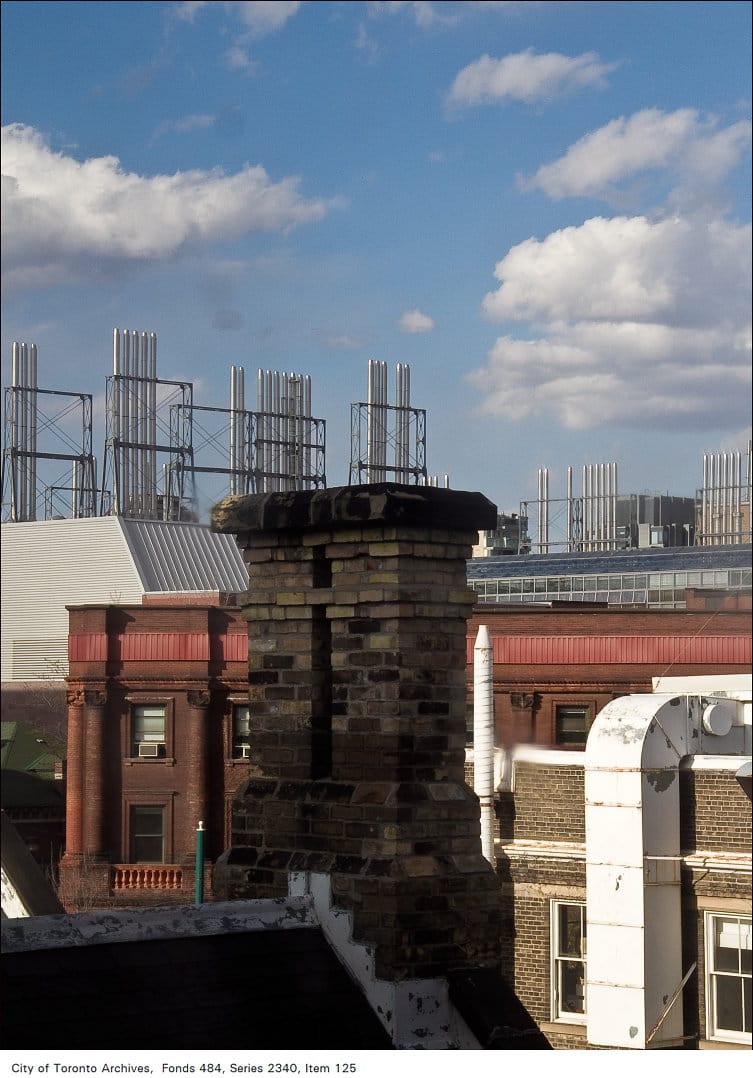

- The North Borden Building lost its brick smokestack…but this perspective gained another in 1952 with the completion of the Russell Street Central Steam Plant.

- Towers sprouted in the background include the McLennan Physical Laboratories building (left side, completed in 1967) and the Theory Condominium building (back right, opened in 2021).

- Another example of the extinction of awnings.

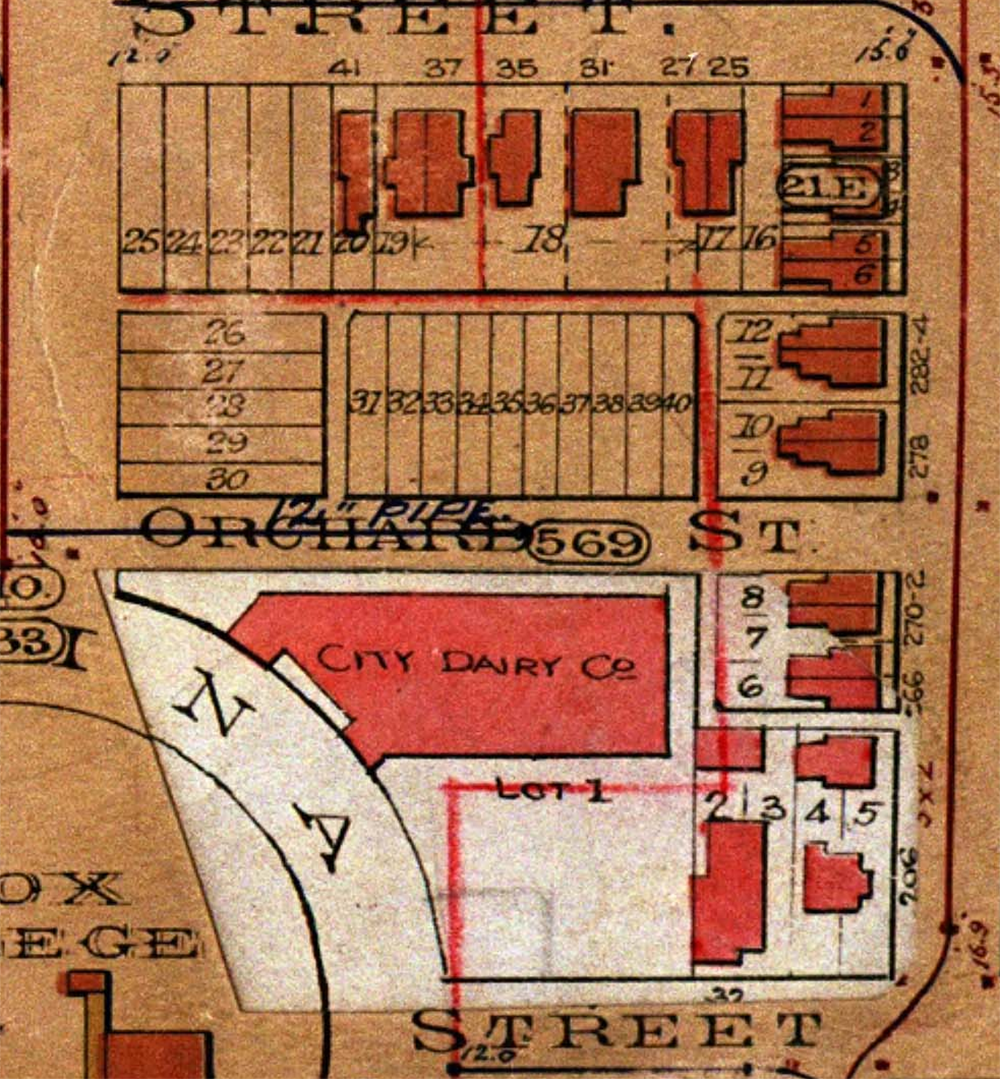

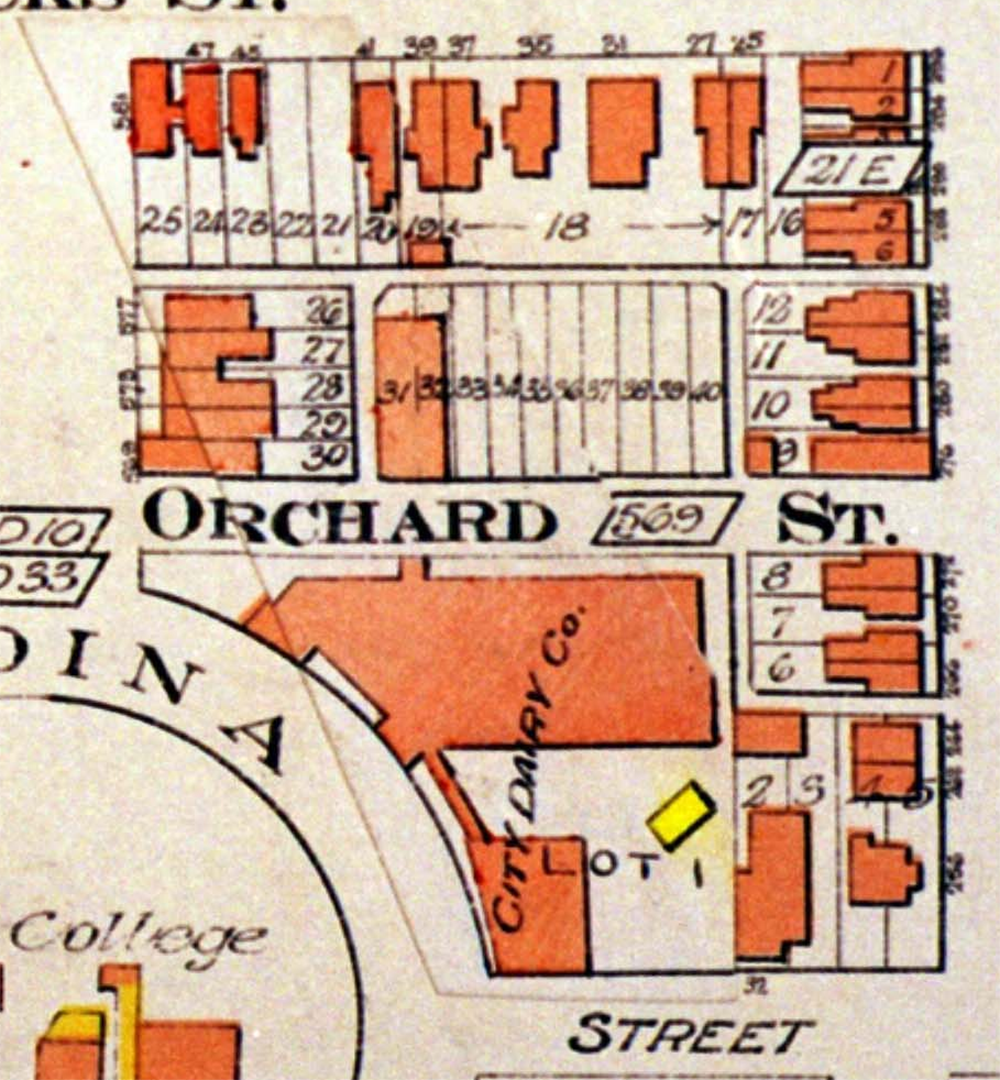

1899, 1903, 1913, 1923 fire insurance maps and 1947, 1959, 1969, 1977, 1987, and 2024 aerials, City of Toronto Archives

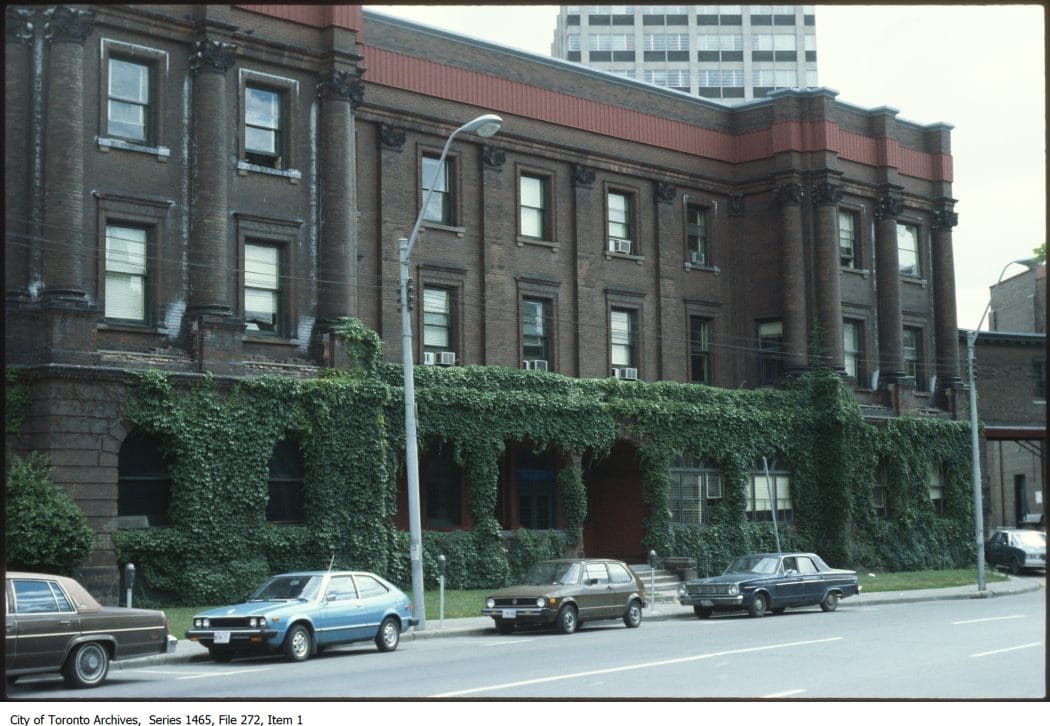

But still–in general, the North Borden Building remains recognizable, which is pretty wild for a 125-year-old dairy processing plant used by a university for more than 60 years, especially as its conversion to academic use was kind of awkward and half-assed. From the 1960s through the 2000s, U of T faculty and students regularly complained about the Borden buildings’ poor states of repair, calling them an eyesore, not fit for purpose, and even a threat to health. Renovations over the last decade appear to have brought the Borden buildings up to snuff, if not necessarily into the future.

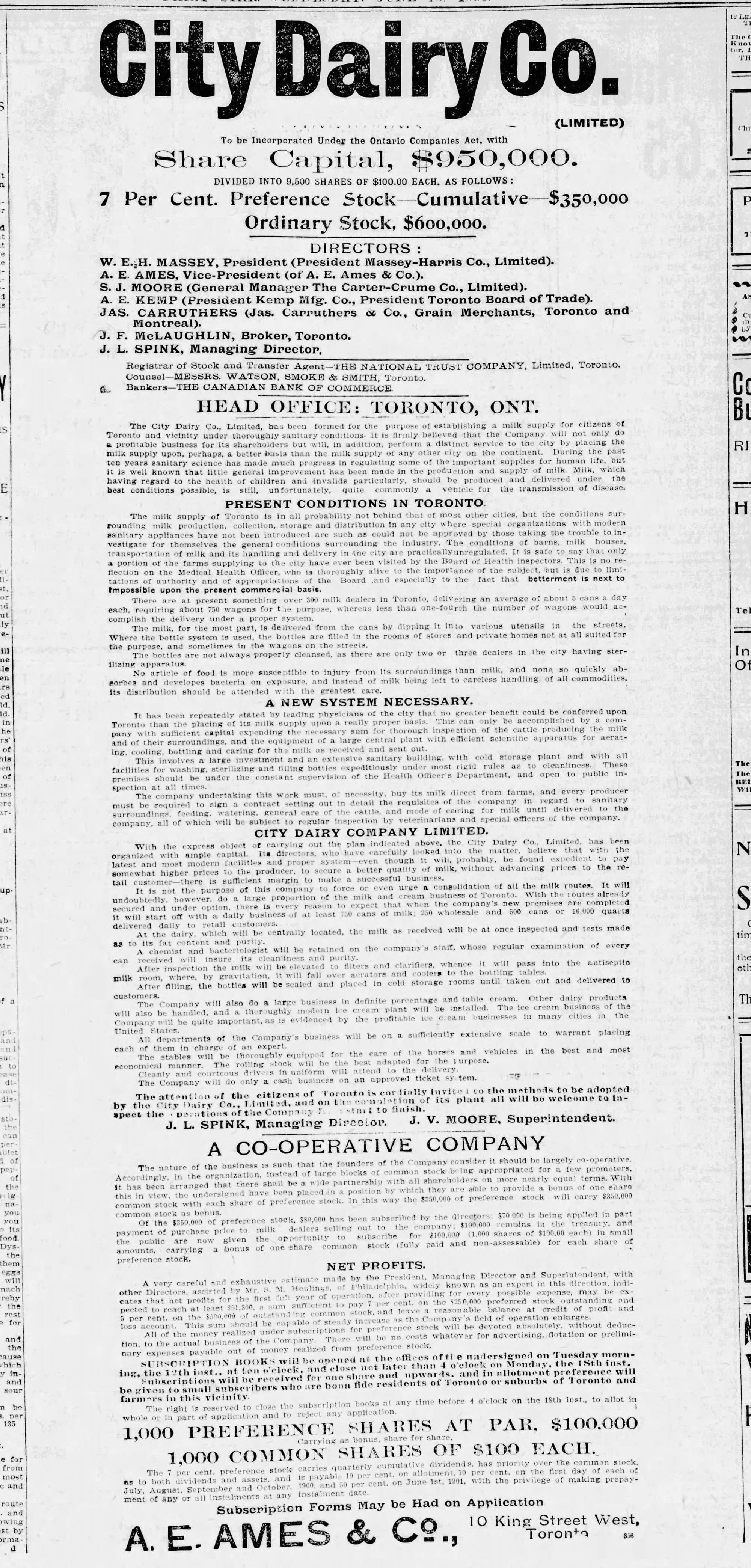

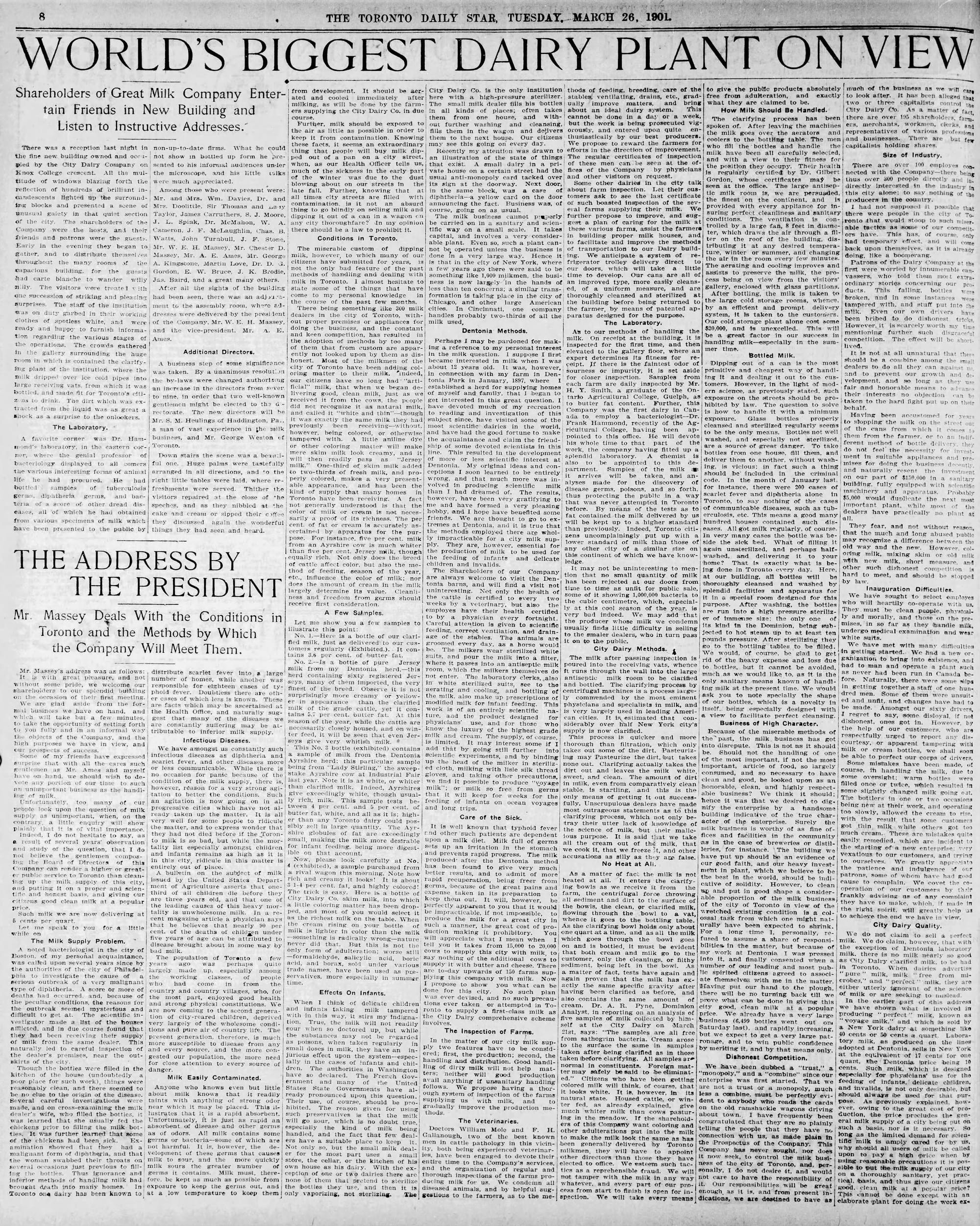

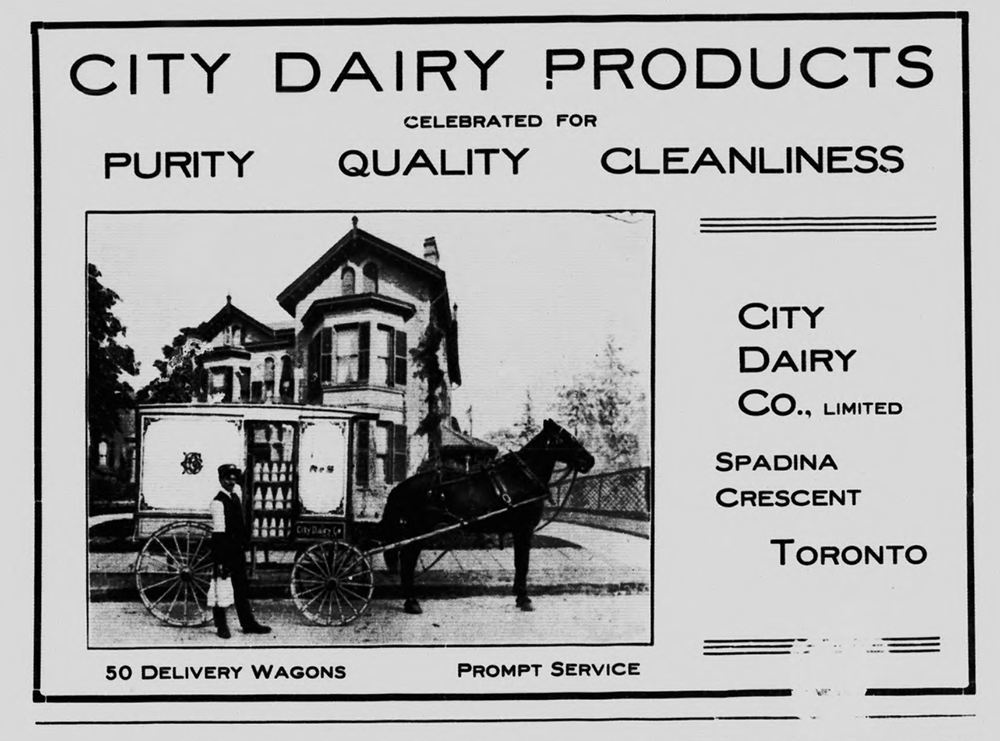

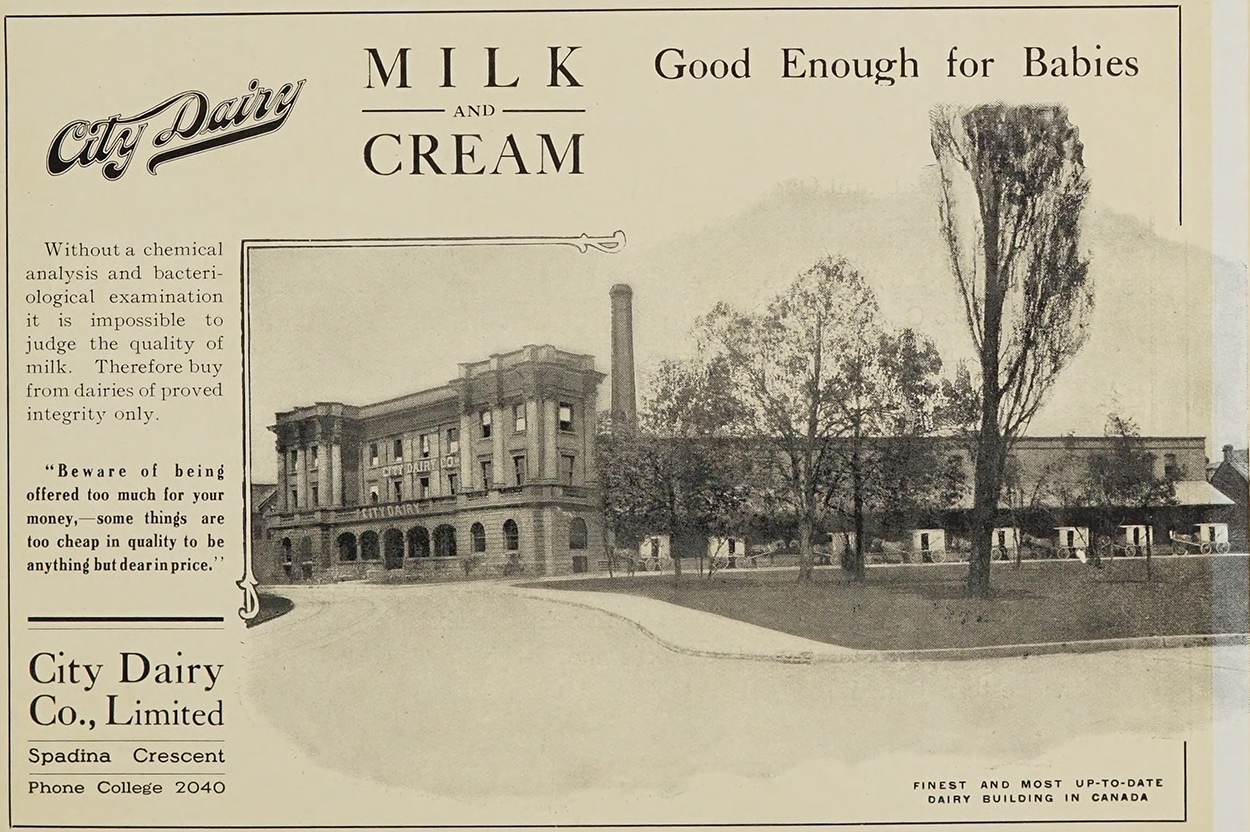

1900, City Dairy Co. incorporated | 1901 ads and articles about the cleanliness of City Dairy Co. milk

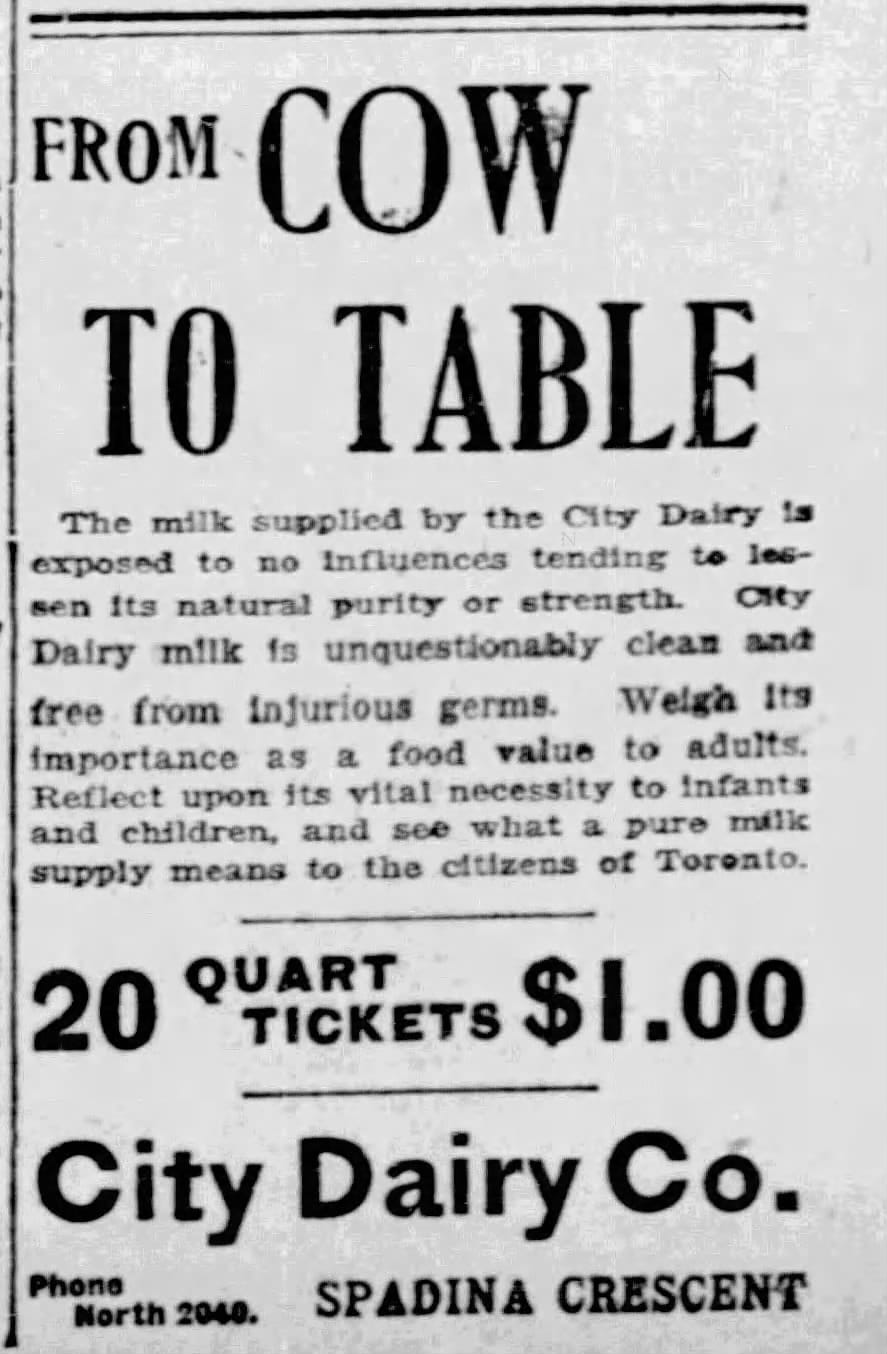

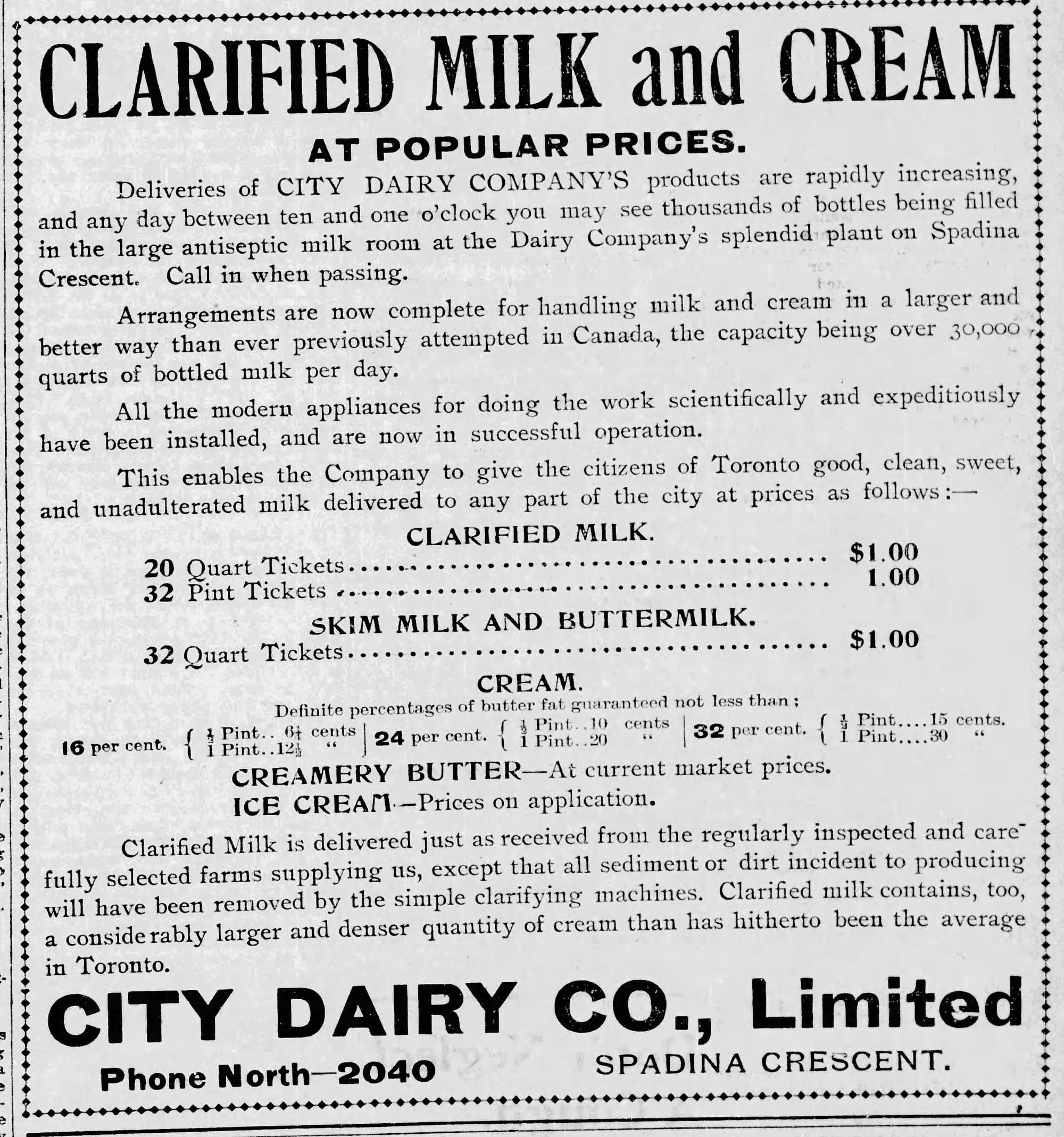

Coming in a kaleidoscope of colors and a major vector of tuberculosis, diphtheria, and typhoid, milk used to be disgusting (...not great that a particular sort of wacko—including the dipshit US Secretary of Health and Human Services—wants to kill kids and bring us back to those days!). Toronto’s City Dairy Company—founded in 1900 by Walter Massey, scion of a major industrialist family—pried open a market by changing that. Built to process milk supplied by cows from Massey’s model Dentonia Park farm, the City Dairy Co. positioned itself as the cleanest, most modern dairy plant in the British Commonwealth when it opened on Spadina Crescent in 1901, boasting about its “cow to table” milk. “Unquestionably clean” milk, “free of injurious germs” was a big deal at a time when other dairies were “colorwashing” their milk with dyes to mask spoilage and impurity and milk-borne disease was a whole category—and that was all before City Dairy installed pasteurization equipment here in 1903, the first pasteurized dairy in Toronto.

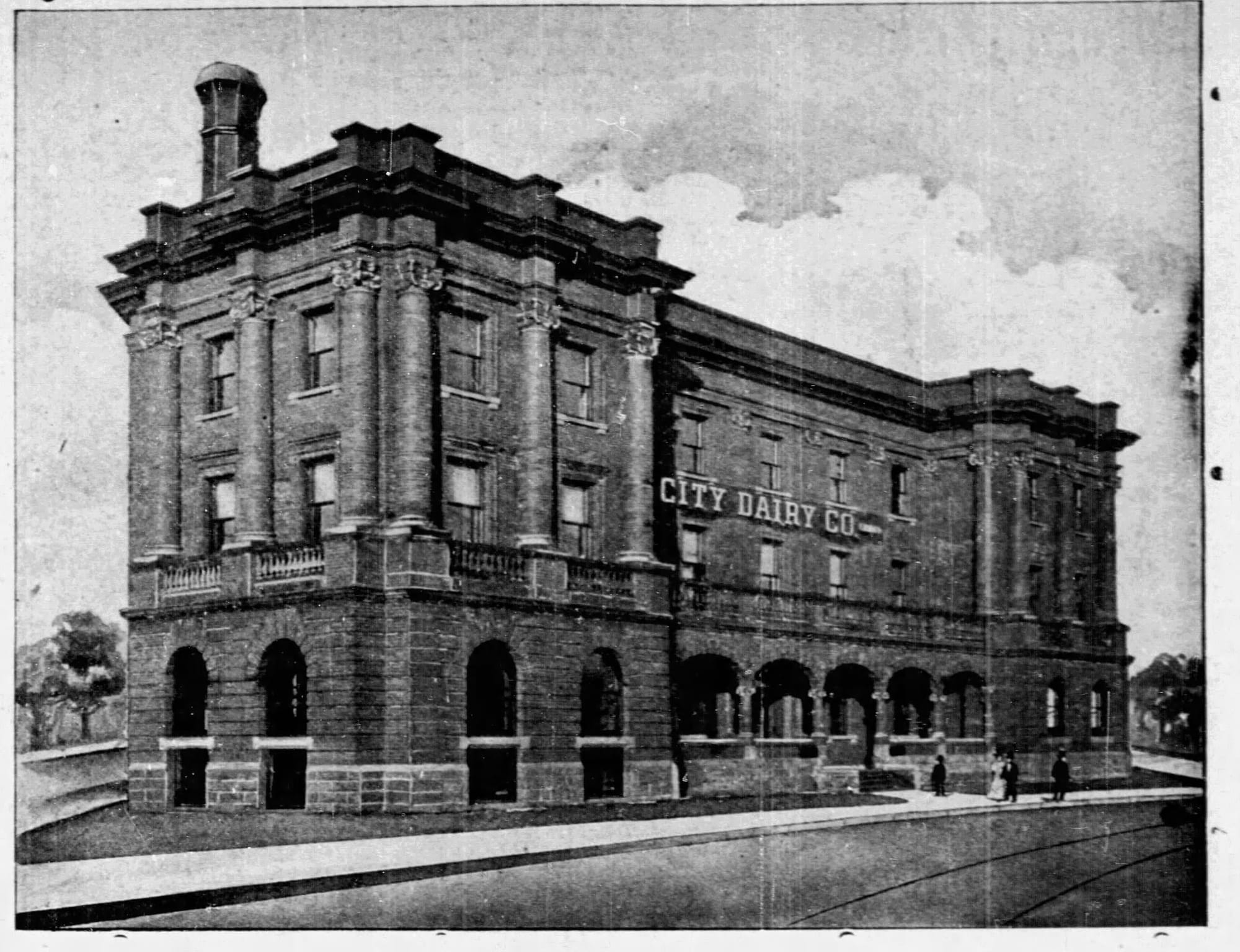

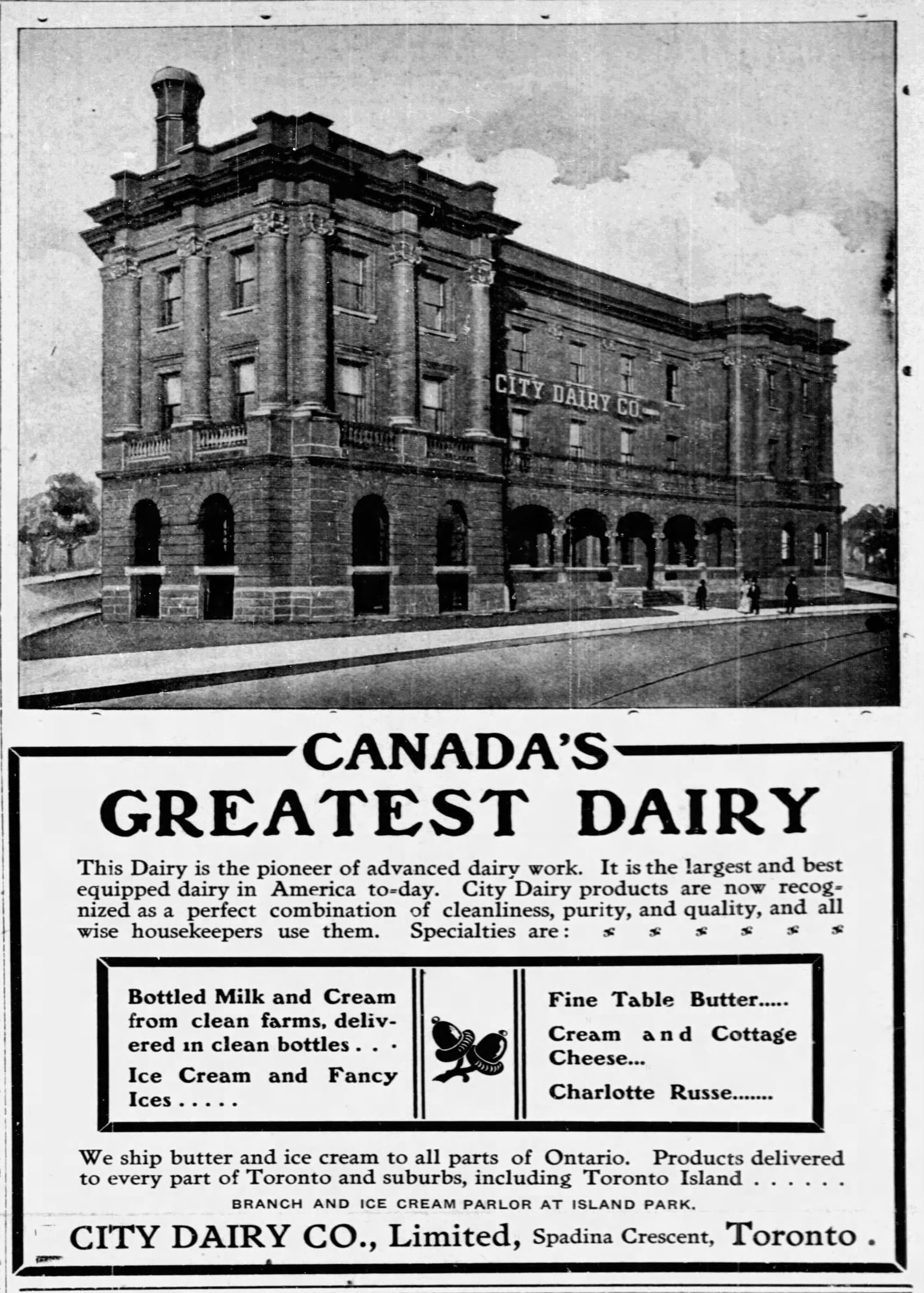

To design the new company’s showcase plant, City Dairy hired architect George Martel Miller—the Massey family’s architect of choice. Like seemingly every firm active in North America from the 1890s to the 1910s, Miller’s firm was wildly prolific. They designed a bunch of homes, civic buildings, churches, and industrial buildings around Toronto, including at least nine for Massey family members or organizations controlled by them.

1901 construction update | 1901, full page article on the dairy plant opening | 1901 articles about proposals to haul freight to the dairy plant using the streetcar lines | 1903 photo | 1906, Digital Archive of Ontario | 1910, Digital Archive of Ontario | 1903 and 1913 fire insurance maps | 1920s, City of Toronto Archives

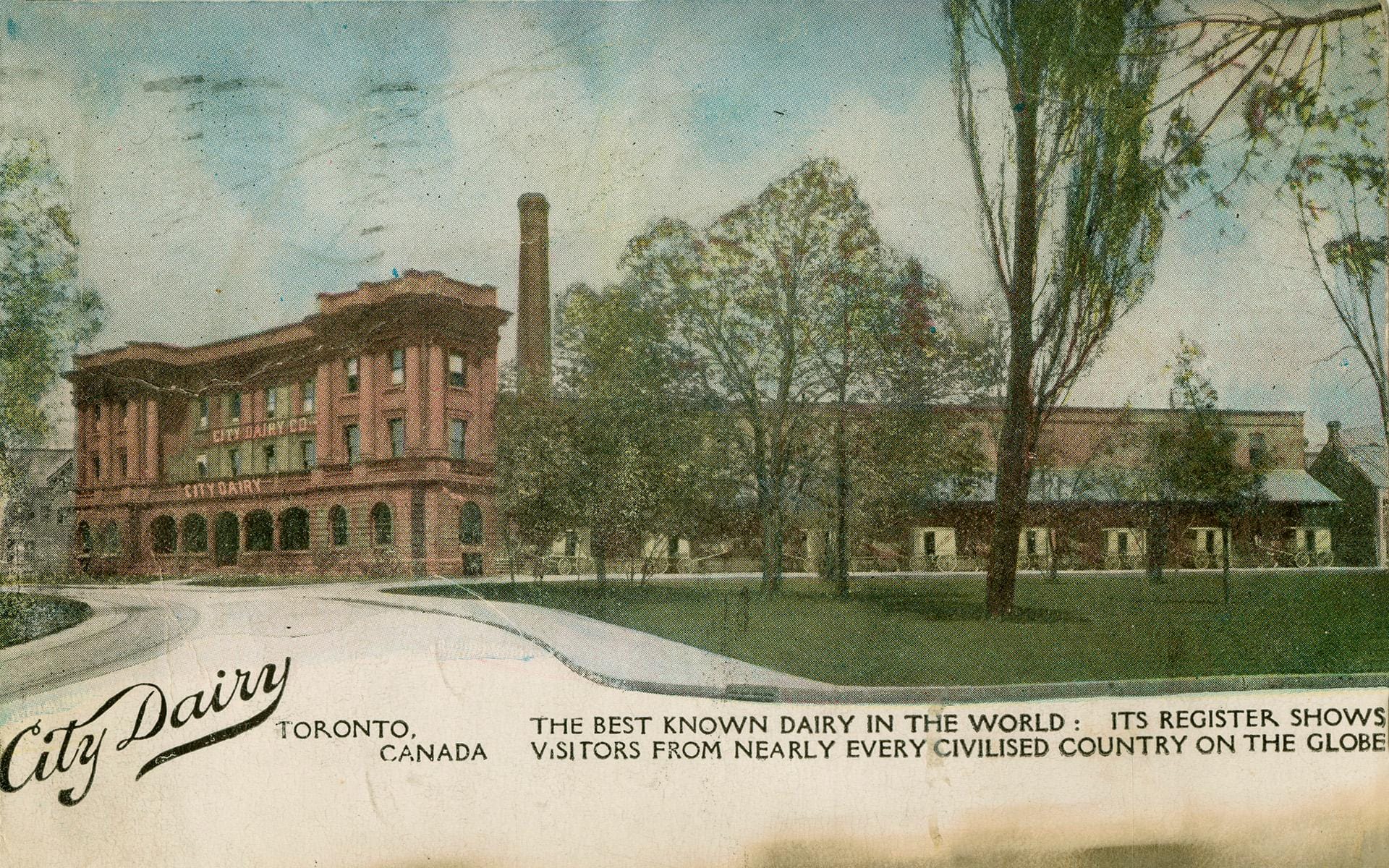

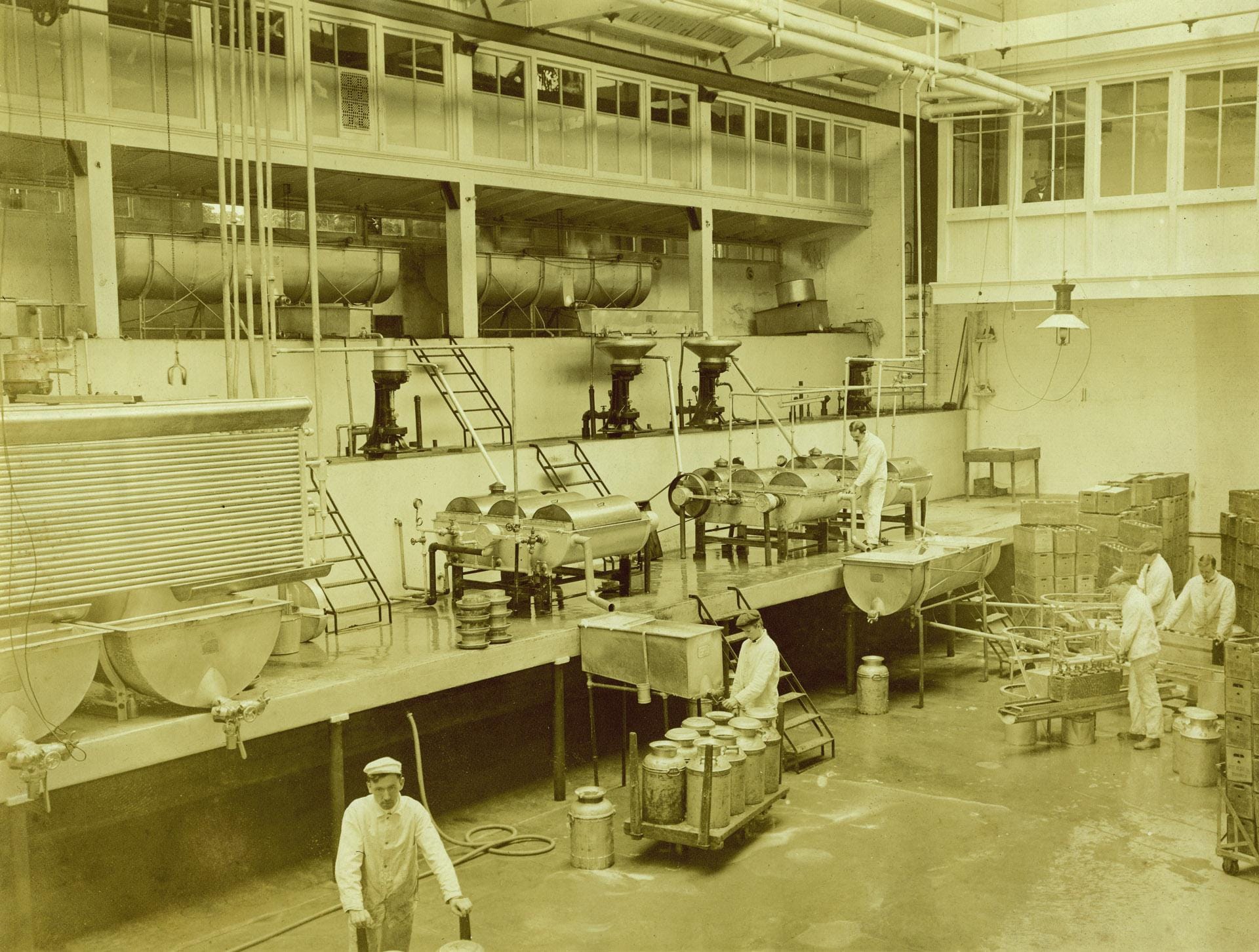

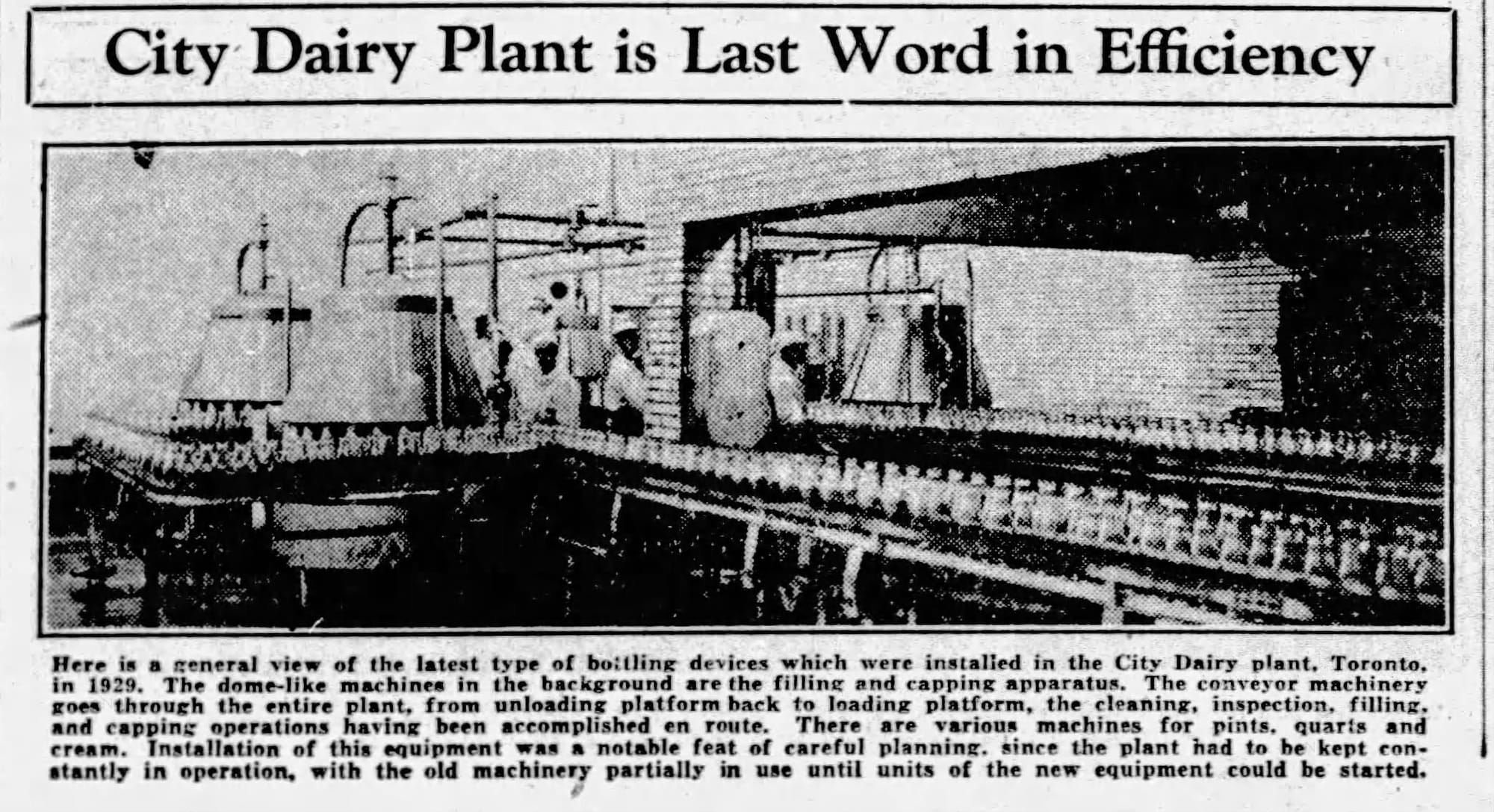

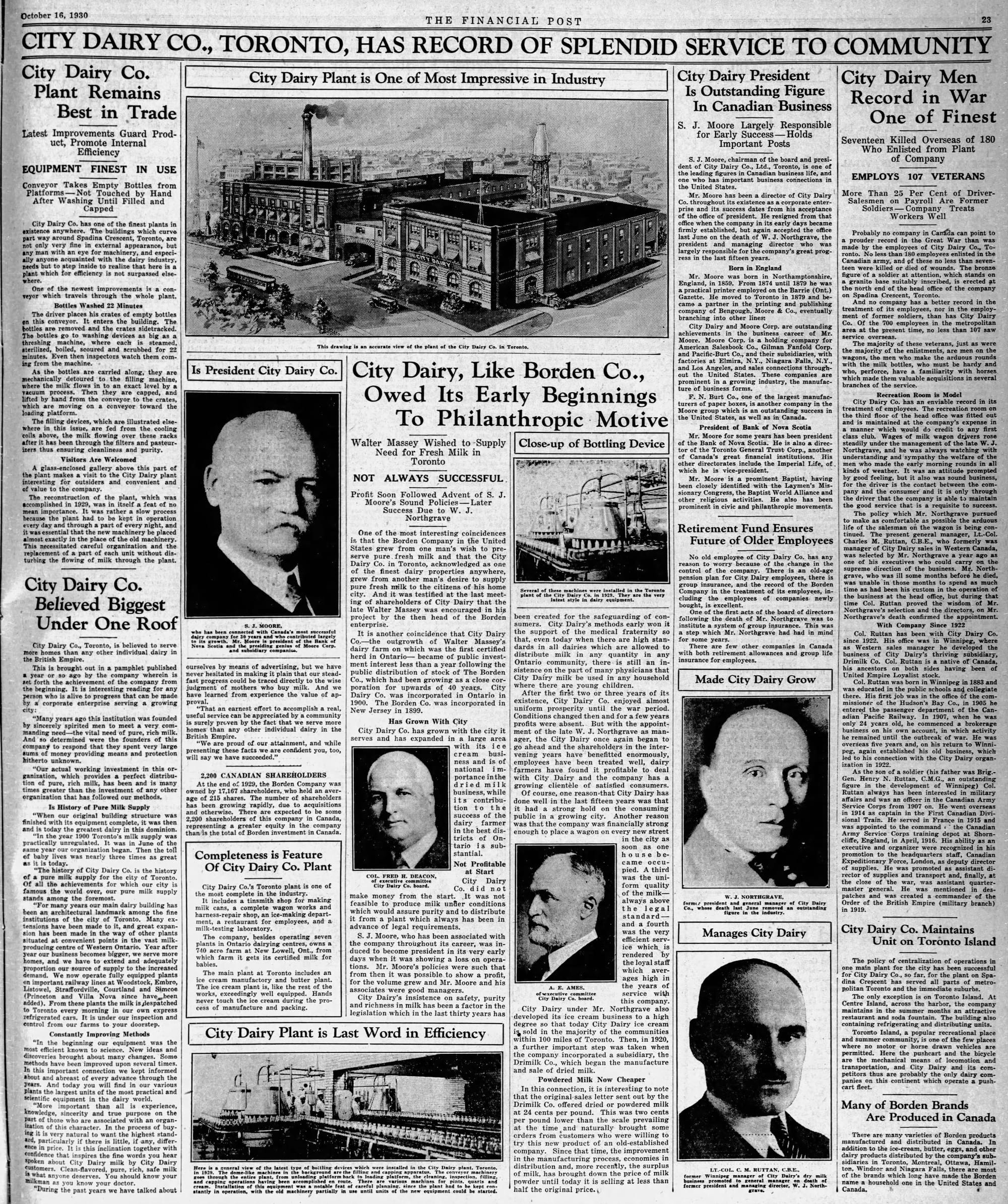

Miller’s original dairy plant—kind of an odd industrial Beaux Arts thing with a nod to Richardsonian Romanesque—housed butter and milk production, cold storage, and offices when it opened in 1901. Producing 365,000 bottles of milk in its first year, less than five years later City Dairy was producing more than 3.5 million, and Miller’s firm was rehired to build an addition—now Borden South—that opened in 1910. At its peak the complex had ice cream manufacturing, a tinsmith shop, a wagon works, a laboratory for testing, stables, and a restaurant—they even floated using the Spadina Avenue streetcar line for freight access. Visitors and tours were encouraged, a way for the dairy to demonstrate their confidence in the cleanliness and purity of their milk.

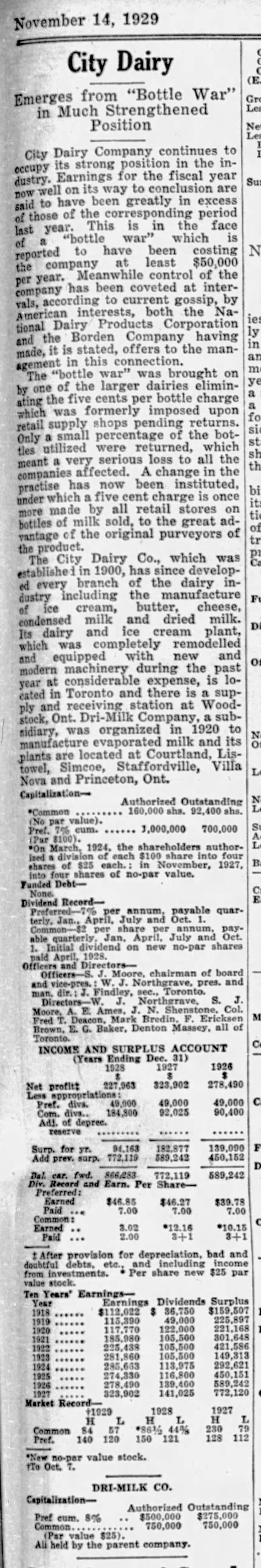

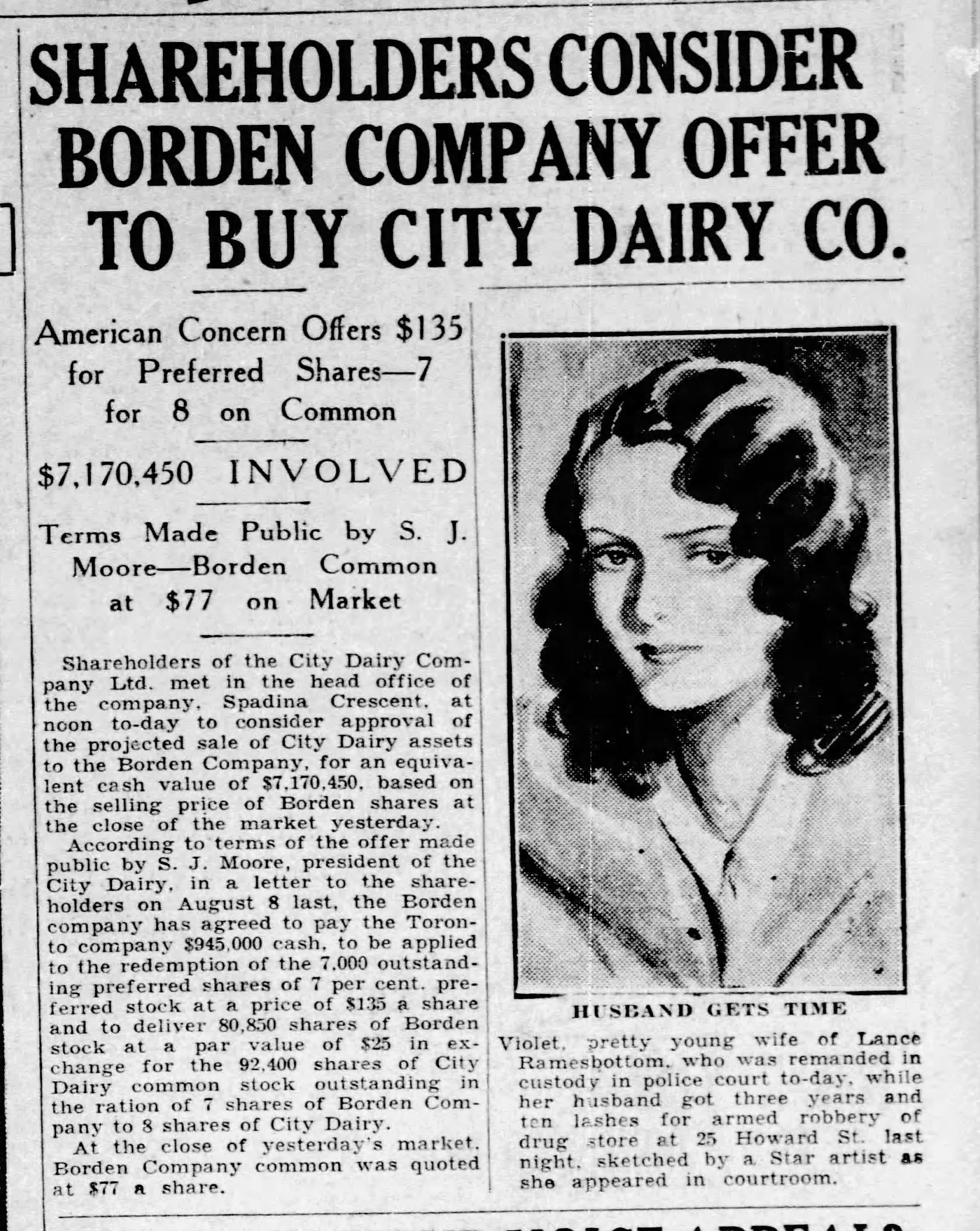

Known for its yellow wagons, City Dairy grew into one of the biggest players in Canada—they regularly claimed that this plant served more homes than any other dairy in the entire British Empire. Their growth caught American attention. American dairy giant Borden acquired City Dairy for CAD $7m in 1930 (the equivalent of $93m USD today), and Borden made this facility their Canadian headquarters.

In the 1940s, the Canadian government experimented on indigenous kids in residential schools, intentionally malnourishing them in order to study the effects—the First Nations nutrition experiments, an even sicker layer to an already shameful part of the Canadian story. Through decisions made from their offices here, Borden participated in those experiments, with the idea that by restricting nutrients to those kids, they could establish a baseline for the nutritional benefits of milk that would help them shift more product. Heinous stuff.

1930 articles about the City Dairy Co. complex and its acquisition by Borden | 1940 in front of the building, City of Toronto Archives | 1948 photo, City of Toronto Archives | 1962 articles about Borden's moving and University of Toronto moving in

By the 1950s, the 50-year-old multi-story industrial dairy in the downtown core of a growing city was just about obsolete. I imagine Borden spent the last decade or so squeezing as much productivity out of their aging plant as they could without making serious investments in modernization. In 1962, they moved to a modern, single-story dairy plant out in North York, and the University of Toronto moved into the building.

Demolishing the Borden buildings and replacing them with purpose-built academic space probably would have been the easy move, but an expanding U of T already had a massive capital building program underway. A bunch of departments—sociology, anthropology, and forestry—moved into the Borden Buildings temporarily…and then the university just kind of let them linger for decades.

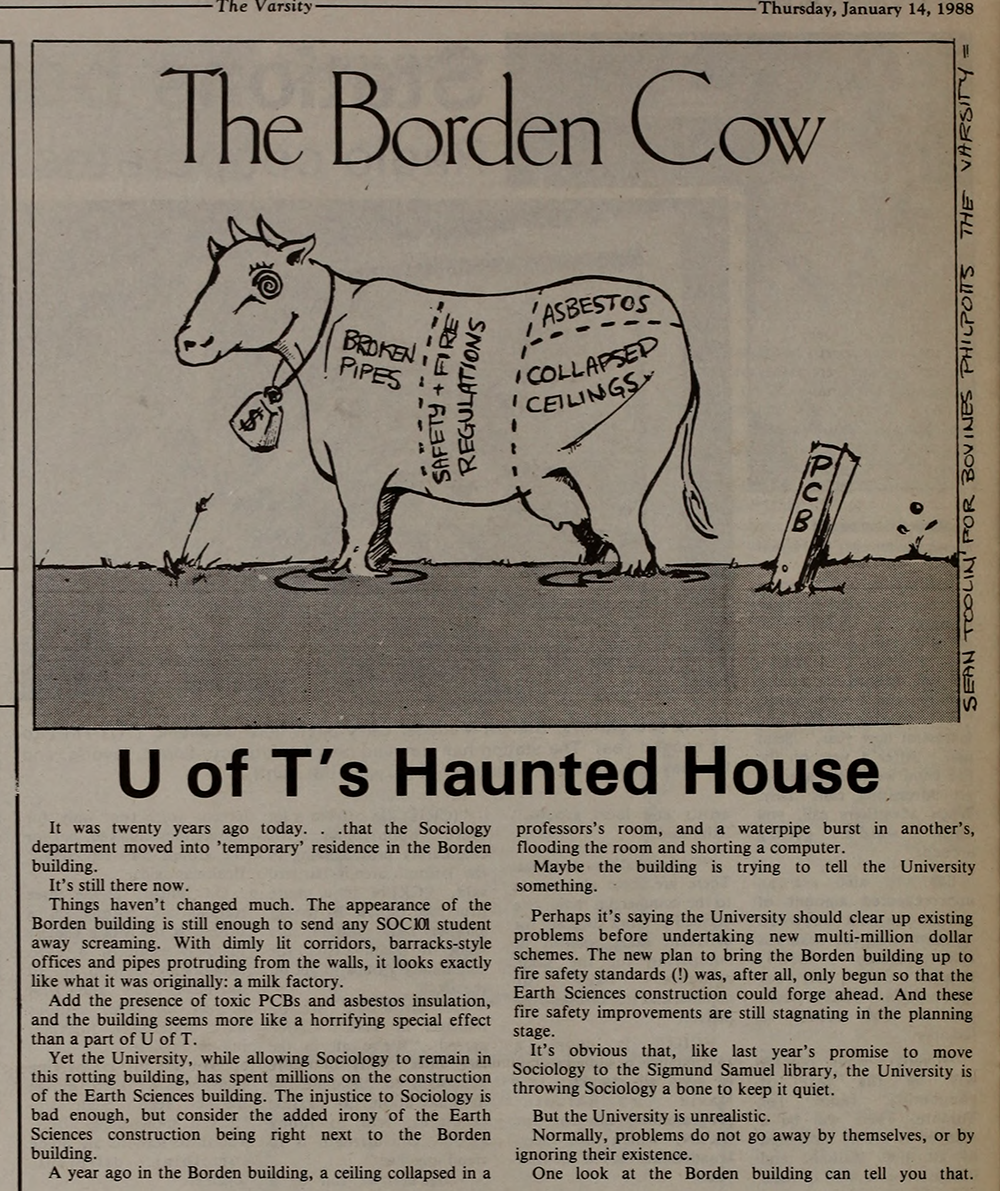

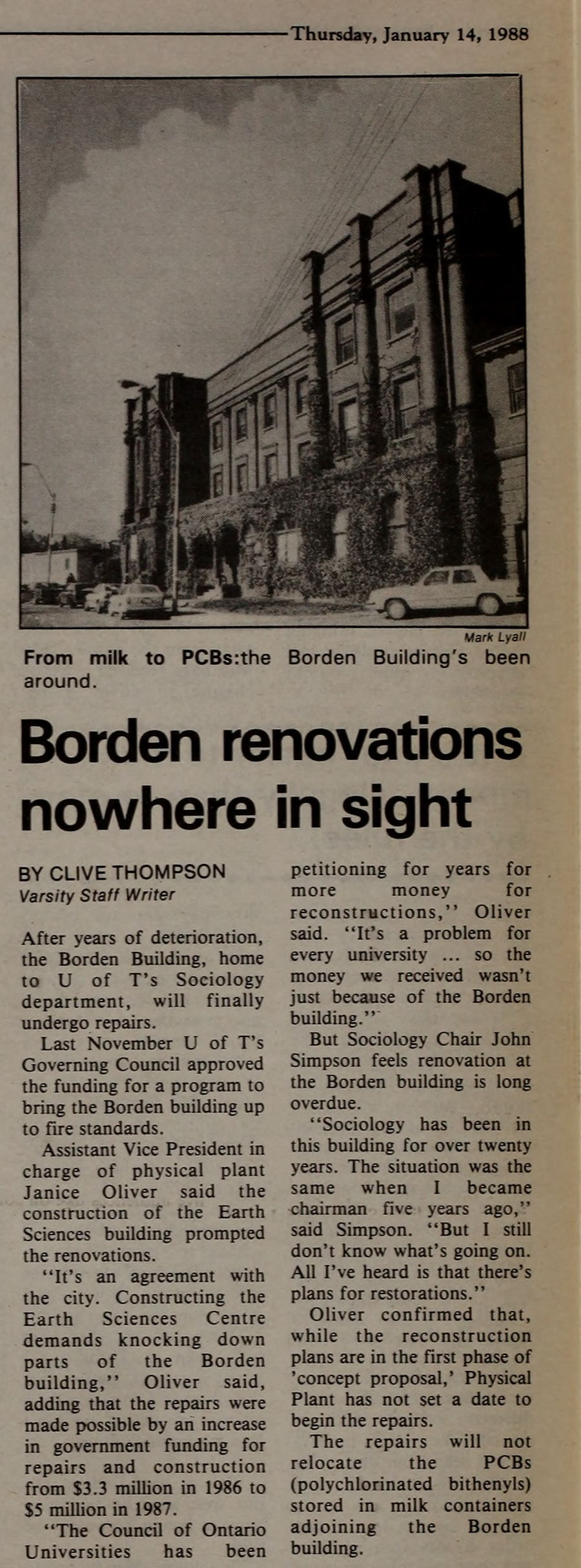

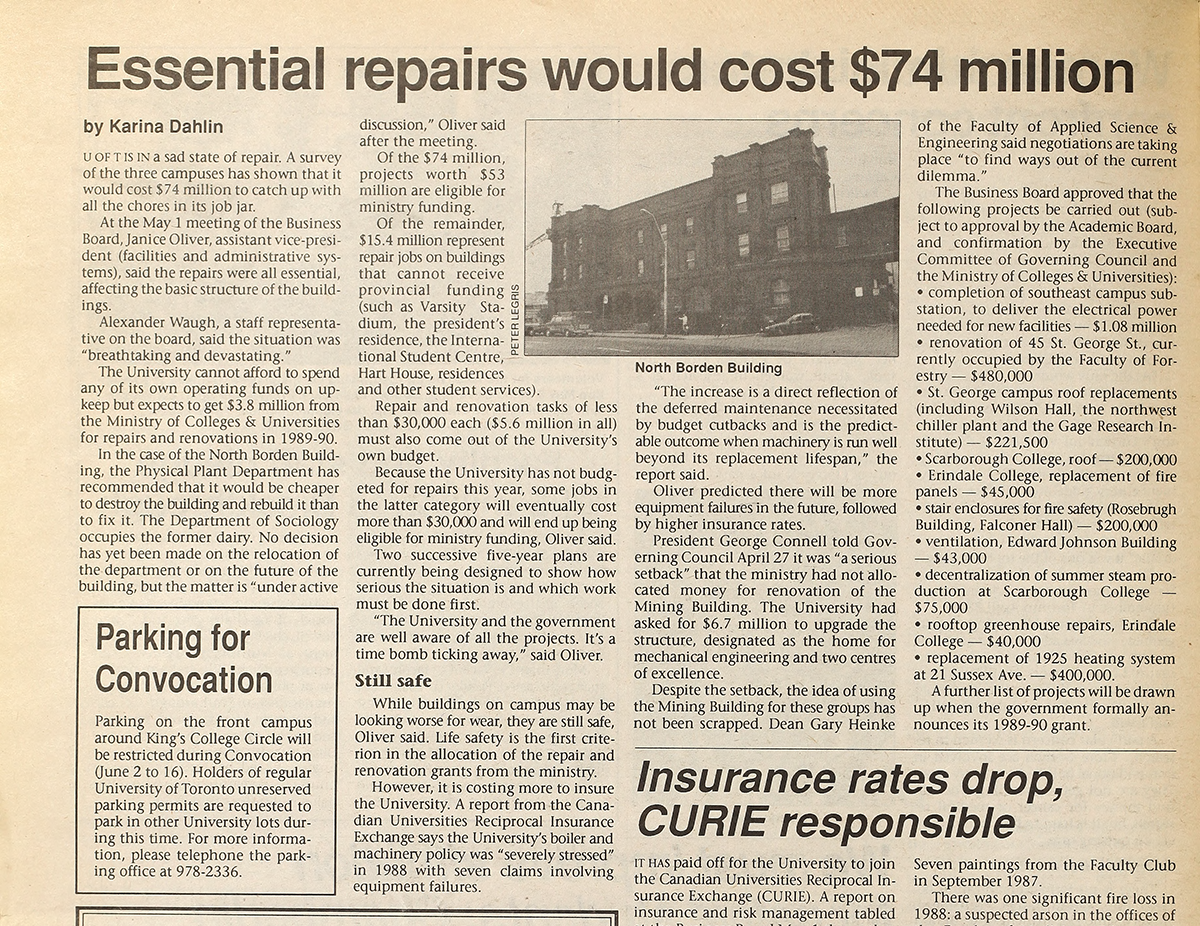

1967 in the Varsity, the Internet Archive | 1974, University of Toronto Graduate, the Internet Archive | 1980, asbestos crumbling, The Varsity, the Internet Archive | 1982, the Varsity, the Internet Archive | 1983, go-ahead for renovation, the Varsity, the Internet Archive | 1987, deteriorating conditions, the Varsity, the Internet Archive | 1987 cartoon, the Varsity, the Internet Archive | 1987, renovations nowhere in sight, the Varsity, the Internet Archive | 1989, essential repairs, the Varsity, the Internet Archive

It seems like this was actually a pretty half-assed case of adaptive reuse—students and faculty did their best to avoid the crumbling Borden Buildings. Labeled “U of T’s Haunted House”, the poorly ventilated buildings were full of asbestos and PCBs, and professors sought out cross-appointments with other departments so they could have an office elsewhere. Deferred maintenance piled up, and by the late 1980s the buildings needed at least $74m in repairs. It doesn’t seem like the university ever really undertook the full-scale (and full price) restoration the buildings needed to function as useful modern academic space, instead fixing problems piecemeal when they became too serious to ignore.

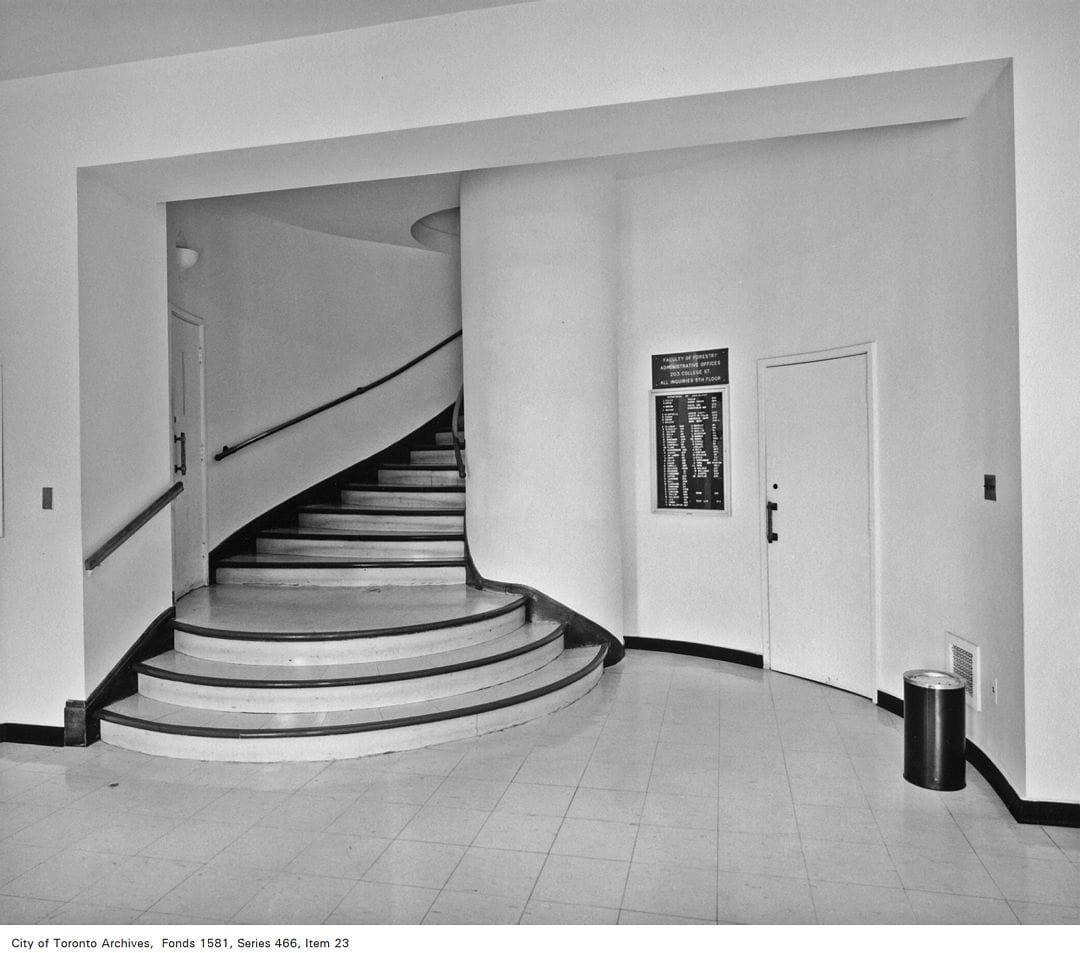

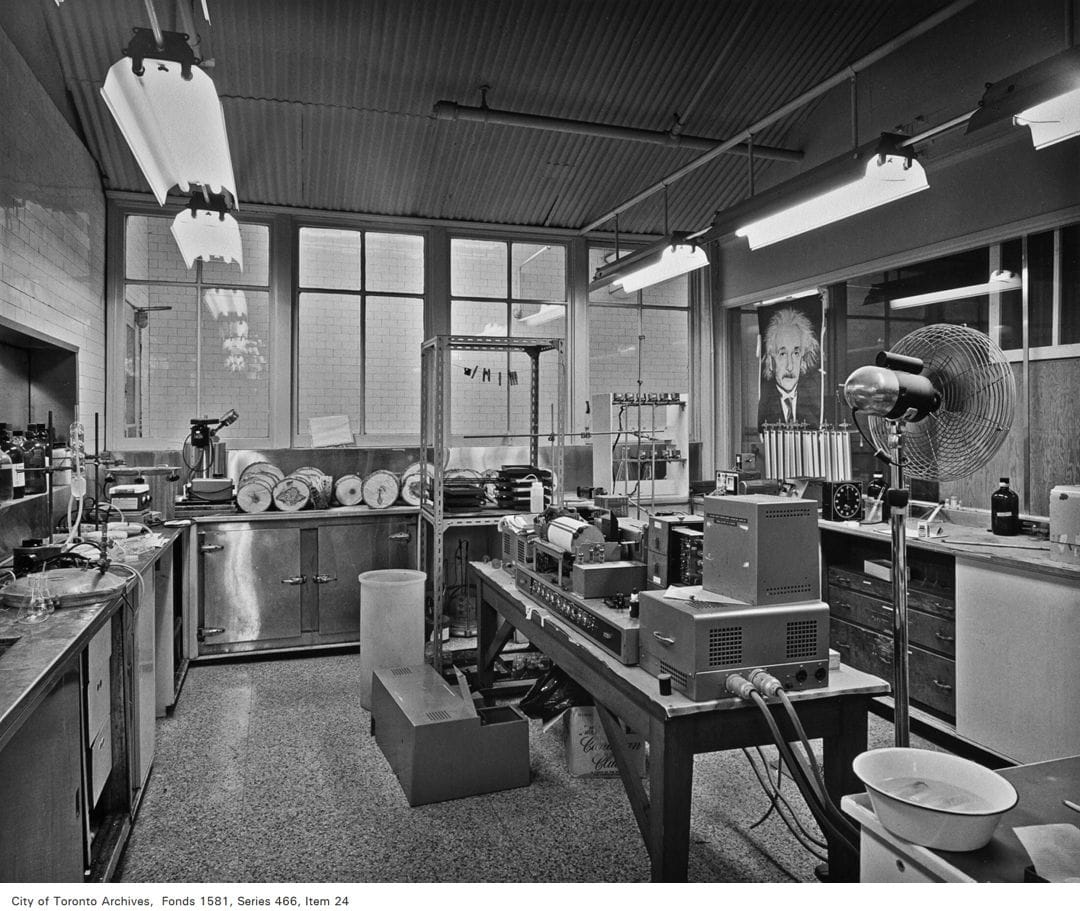

1980s-1990s, Bancroft looking west to Borden Building North, City of Toronto Archives | 1980s-1990s, Borden Building North, City of Toronto Archives | 1983, stairway, City of Toronto Archives | 1984, forestry department, City of Toronto Archives | 2010, James Jay Allen, City of Toronto Archives

The sociologists, anthropologists, and foresters eventually moved to other buildings. In the mid-2010s, the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design temporarily moved into the Borden Buildings as the University of Toronto turned One Spadina Crescent across the street into that faculty’s flashy new home (the FALD’s Visual Studies department still has classrooms, studios, and a darkroom in Borden South).

The university also moved the Centre for Indigenous Studies and the First Nations House into Borden North, the original City Dairy plant, in the early 1990s. Founded in 1992, the First Nations House is a culturally relevant hub providing student services—cultural programming, academic support, peer mentorship, a space to just be—for indigenous students at the University of Toronto.

Production Files

Further reading:

- City Dairy Toronto: A Yellow Wagon on Every Street by Paul Huntley

- University of Toronto: an architectural tour by Larry Richards

- Historicist: “If It’s City Dairy It’s Clean and Pure. That’s Sure.”

- Made in Toronto – Milk

A few more City Dairy ads.

1903 ad, Illustrated souvenir of the Letter Carriers Association of Toronto, the Internet Archive | 1903 ad | 1909 ice cream and plum pudding ads | 1909, Report on a comprehensive plan for systematic civic improvements in Toronto, the Internet Archive

A couple articles on the building's construction.

1901 construction update | 1902, factories as a way to adorn a city

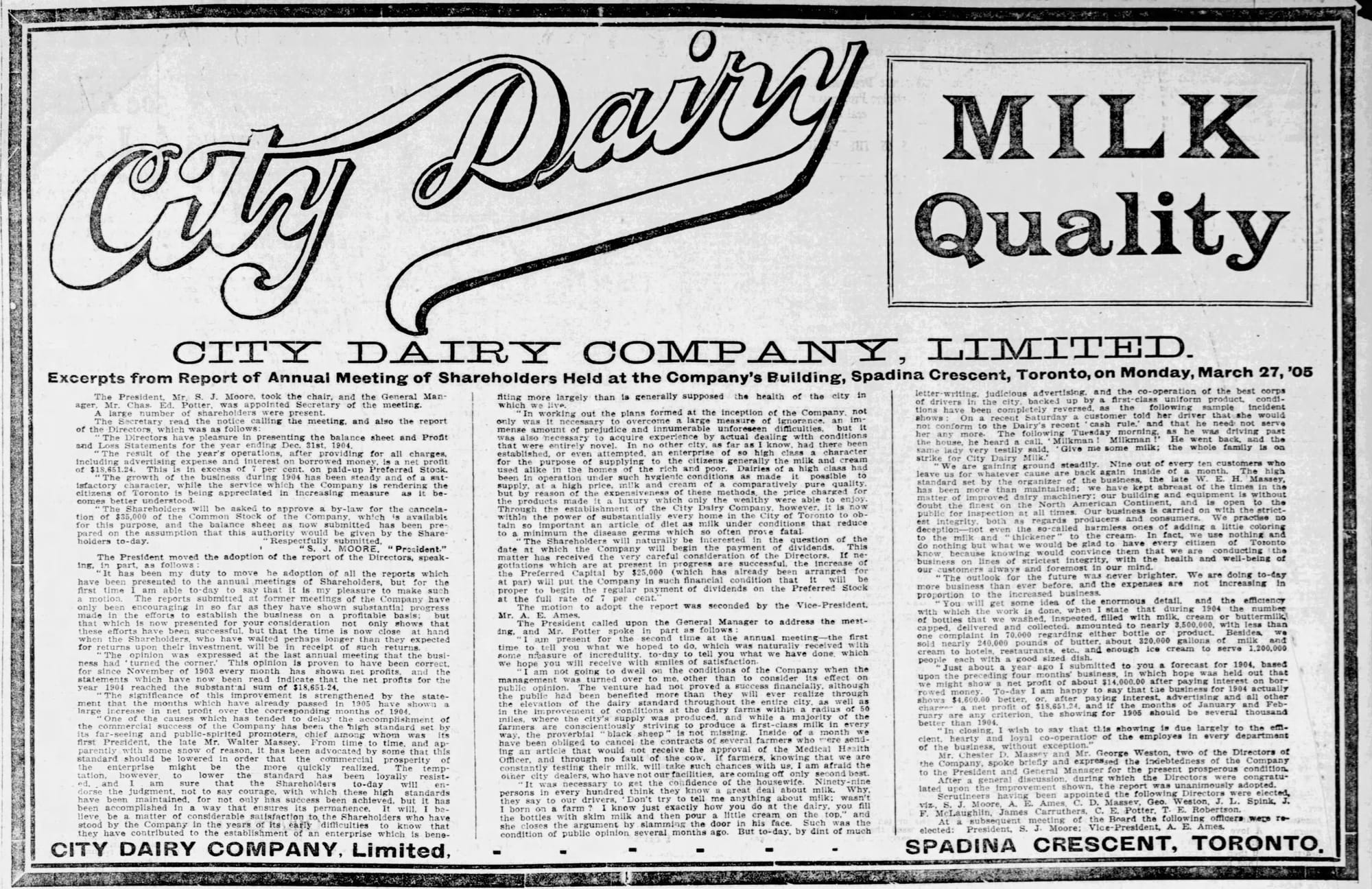

A little bit more on the City Dairy's business and the eventual sale to Borden.

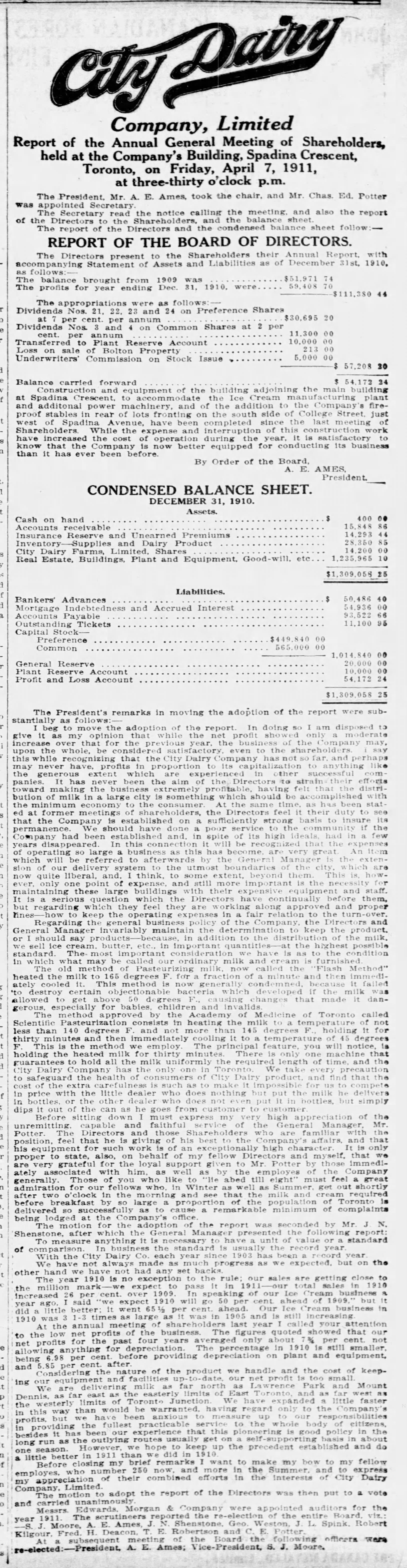

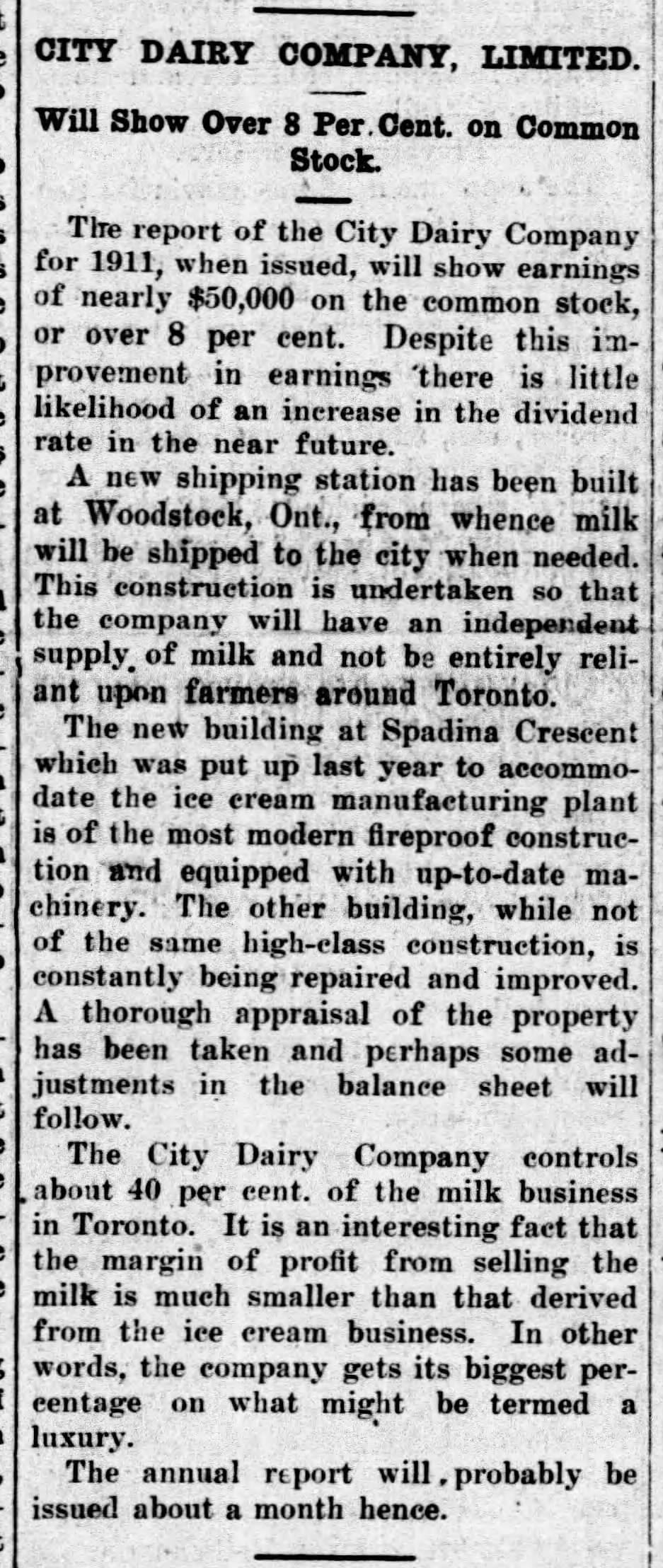

1905, 1911, and 1912 City Dairy Co. annual reports | 1929, City Dairy emerges from "bottle war" | 1930, shareholders consider Borden offer

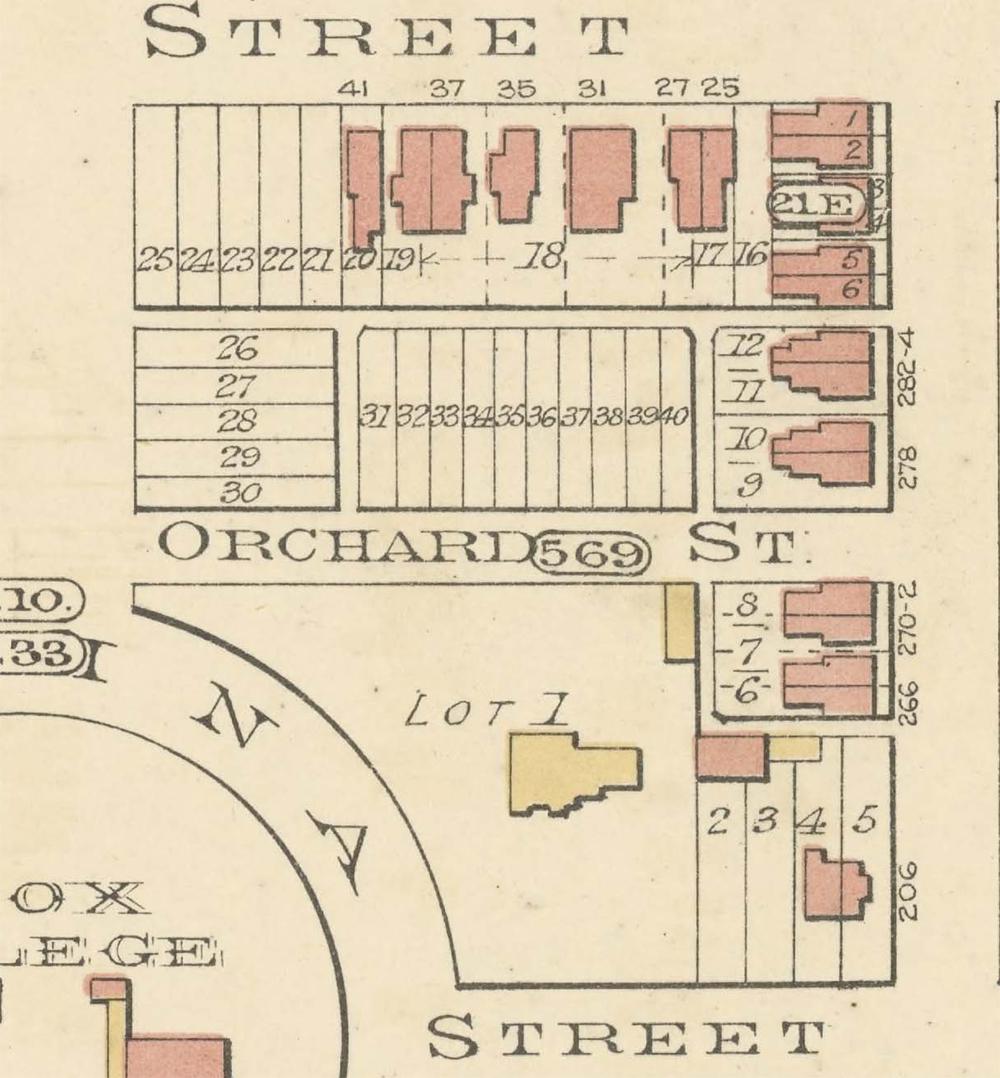

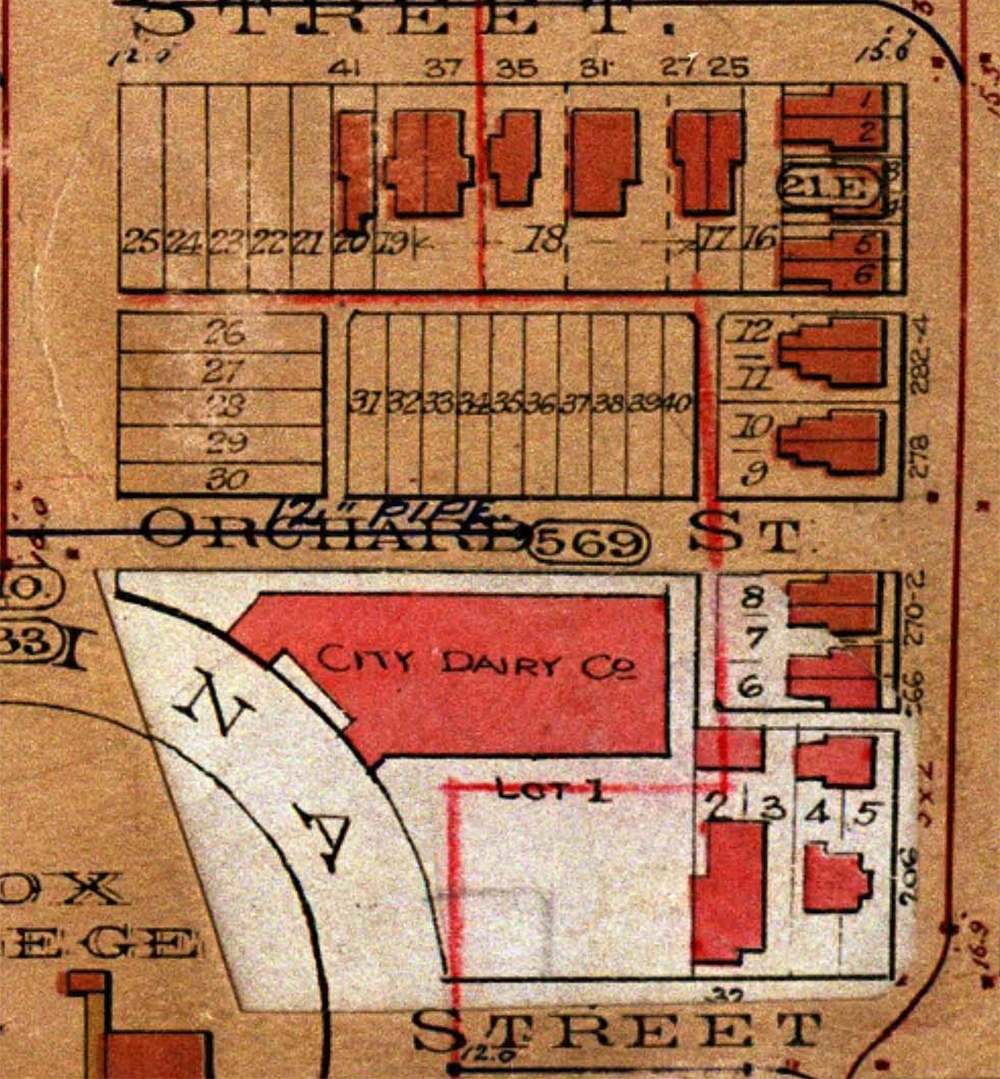

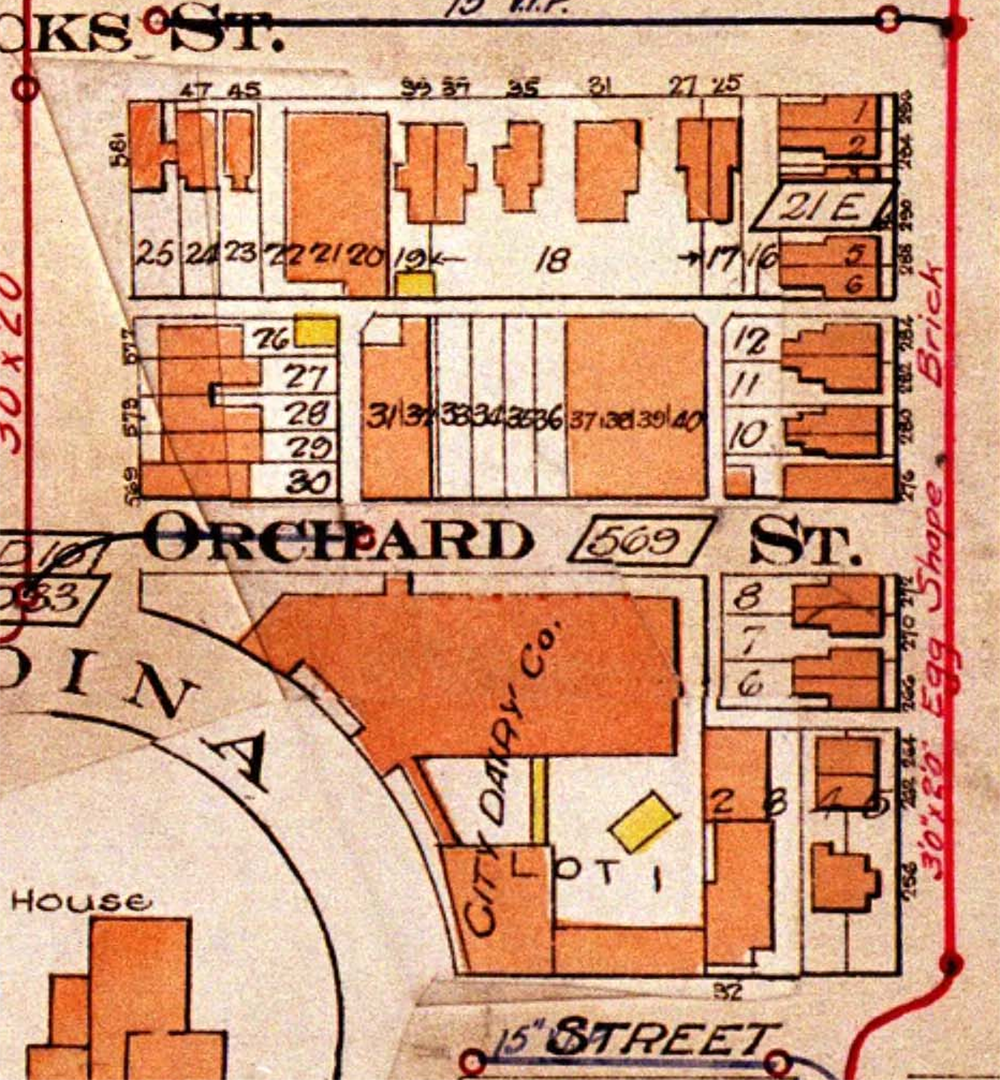

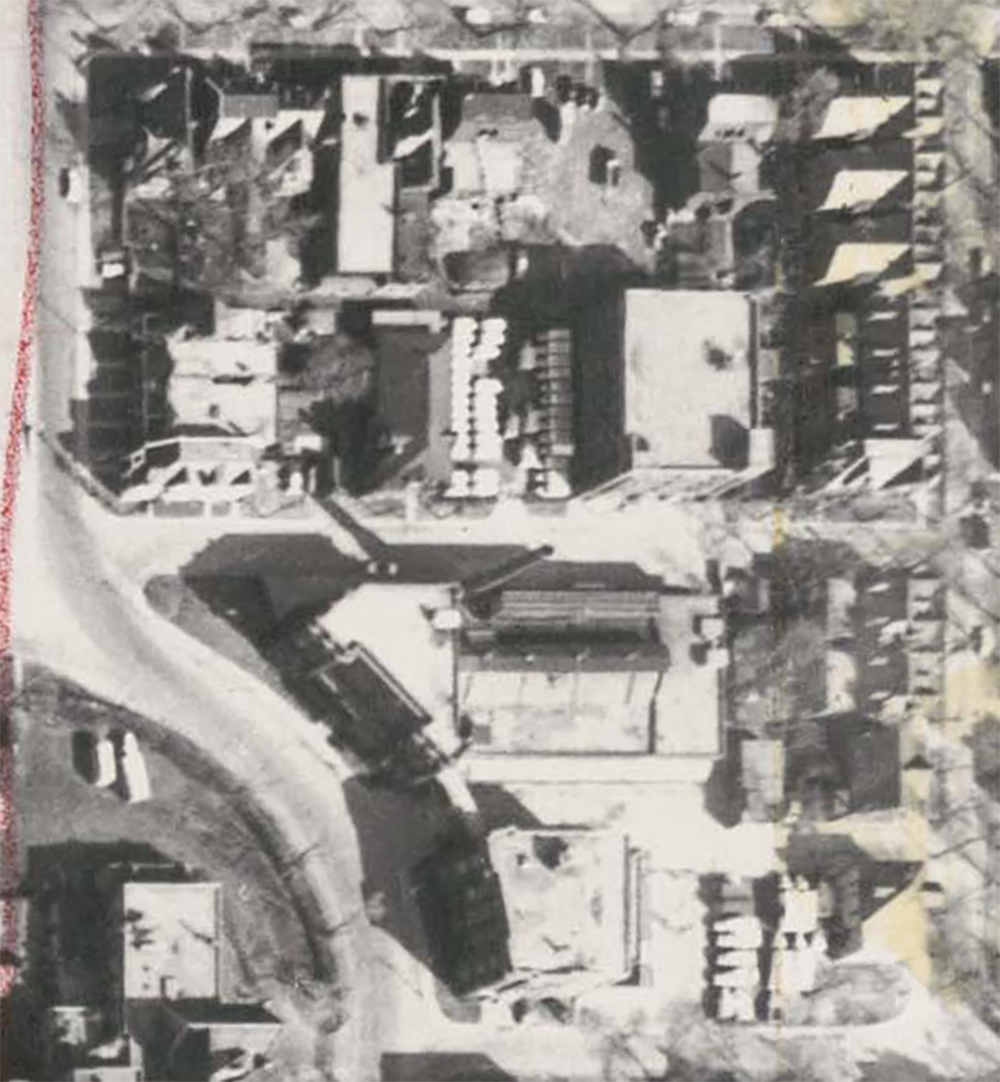

The block in fire insurance and aerial maps from 1899 to 2024.

1899, 1903, and 1923 fire insurance maps | 1947, 1959, 1969, 1977, 1987, and 2024 aerials

Member discussion: