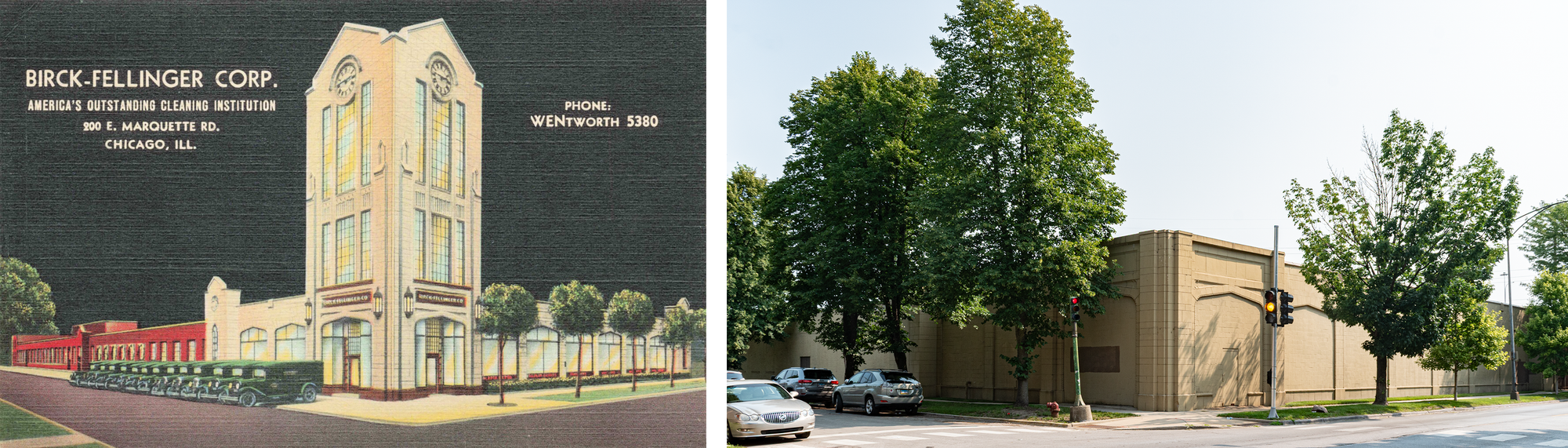

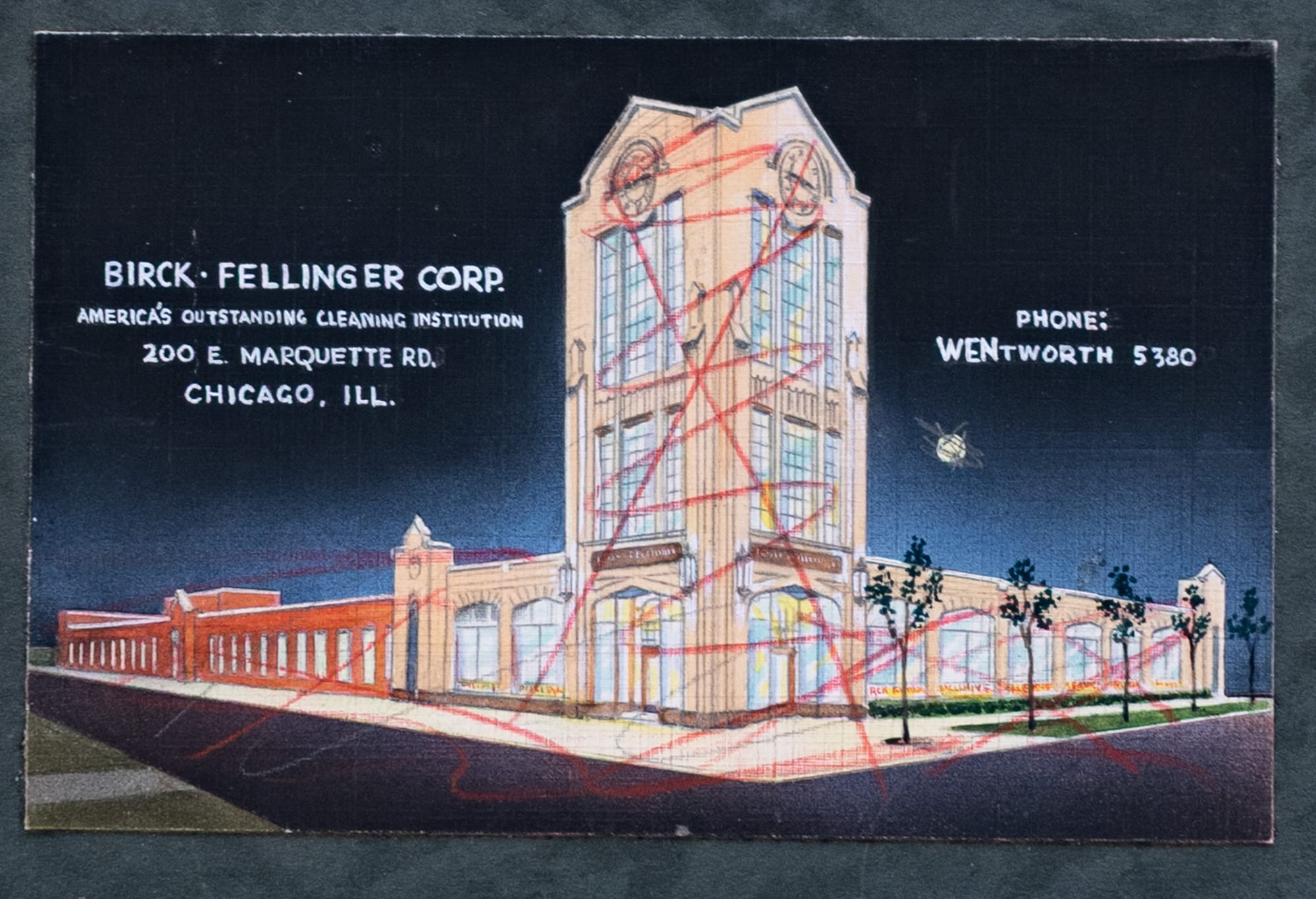

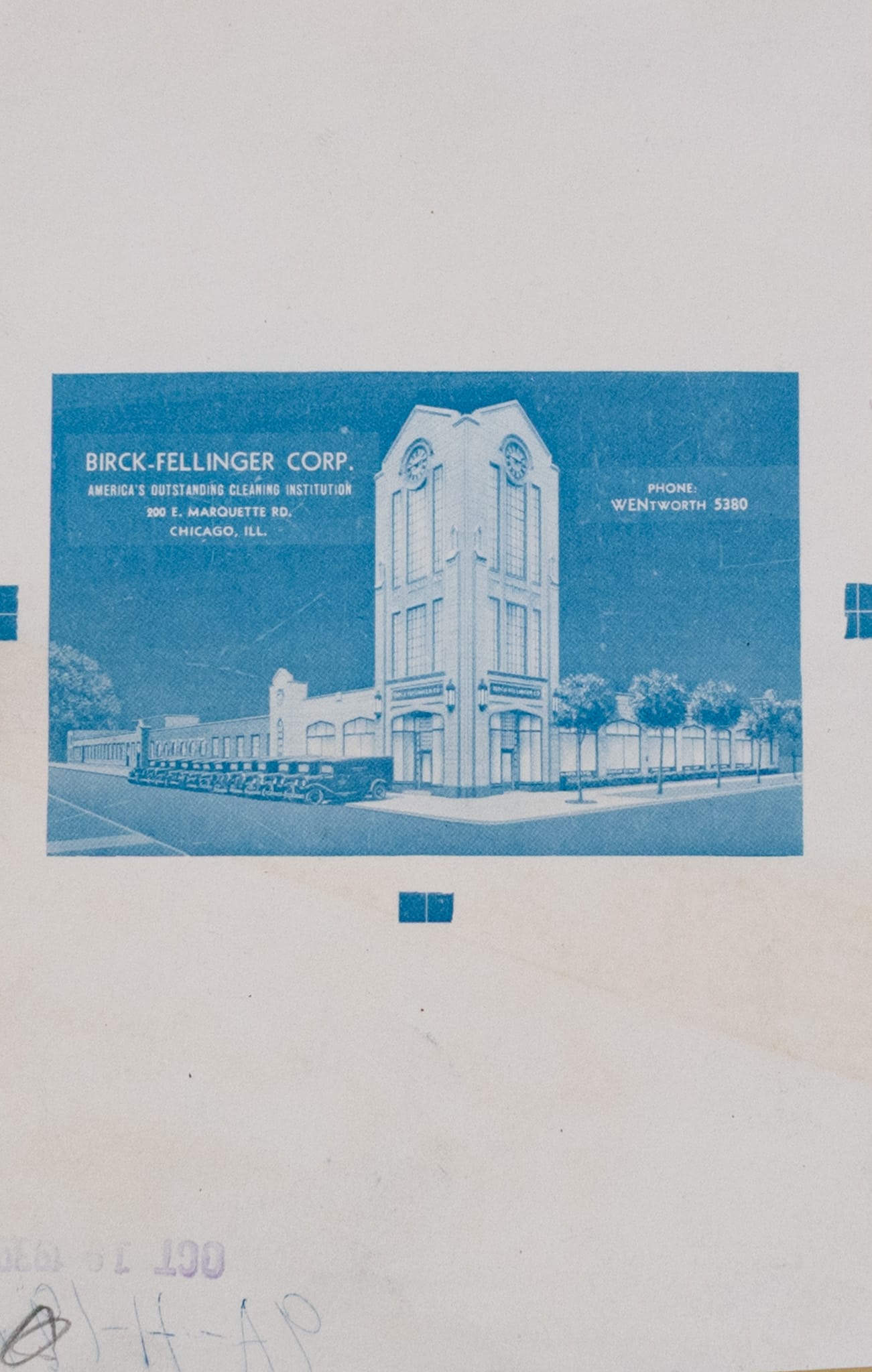

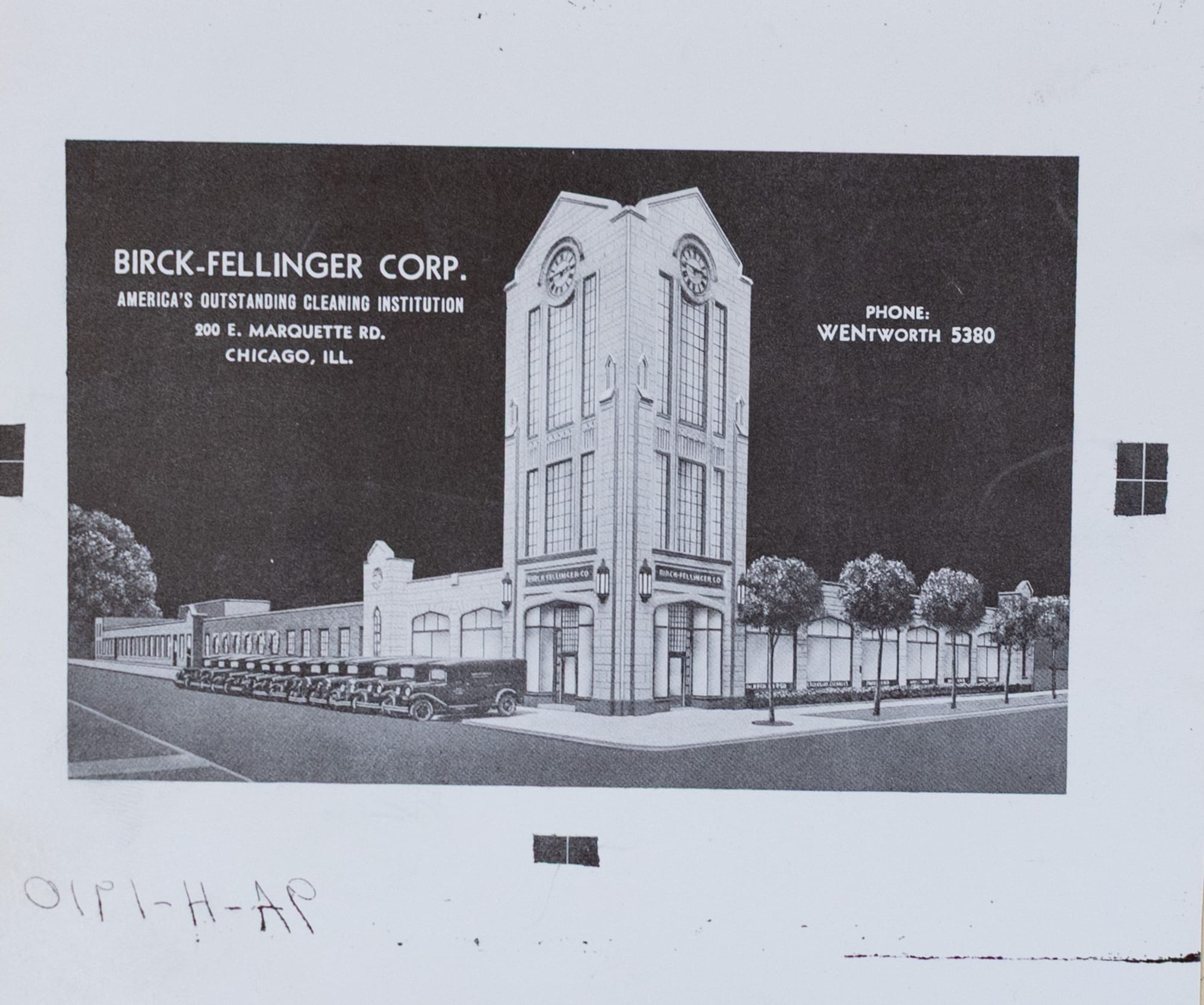

Designed by J.L. McConnell and built in 1928—when brash industrial cleaning plants and massive laundries sprouted smokestacks and water tanks across Chicago—the former Birck-Fellinger plant lost its tower in the late 1980s, as most of those old laundries and cleaners crumbled. Originally constructed for cleaning rugs, the cold storage of furs, and dry cleaning, the utilitarian leftovers of the Birck-Fellinger plant are now part of the Quam Nichols manufacturing complex, makers of commercial loudspeakers. A far cry from the industrial Gothic ambition of the 1920s, but hey—it’s an active manufacturing site in Chicago, which is still pretty neat.

So, what’s changed? Um, well, basically everything—but honestly, no judgement there. Many of these old cleaning plants were demolished, so I was pleasantly surprised to realize that this one was technically still hanging on.

- The arched shape of the old windows is still there, even if they’ve been bricked in.

- The tower—which I imagine held a water tank at the top—appears to have been removed sometime between 1988 and 1990.

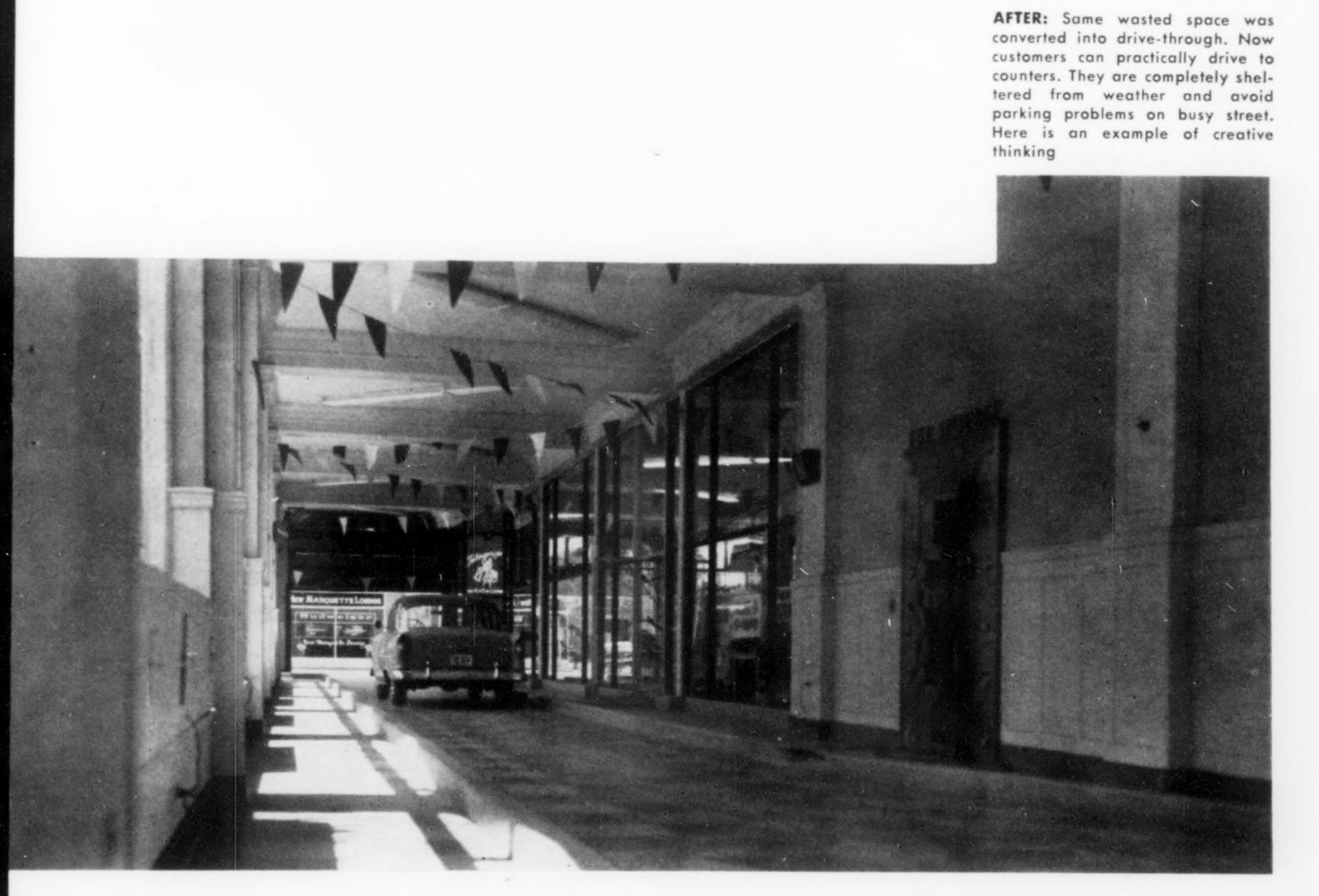

- It's barely perceptible after it was bricked up along with the rest of the windows, but a 1956 renovation punched a hole in the west elevation of the ground floor of the tower to create a drive-through.

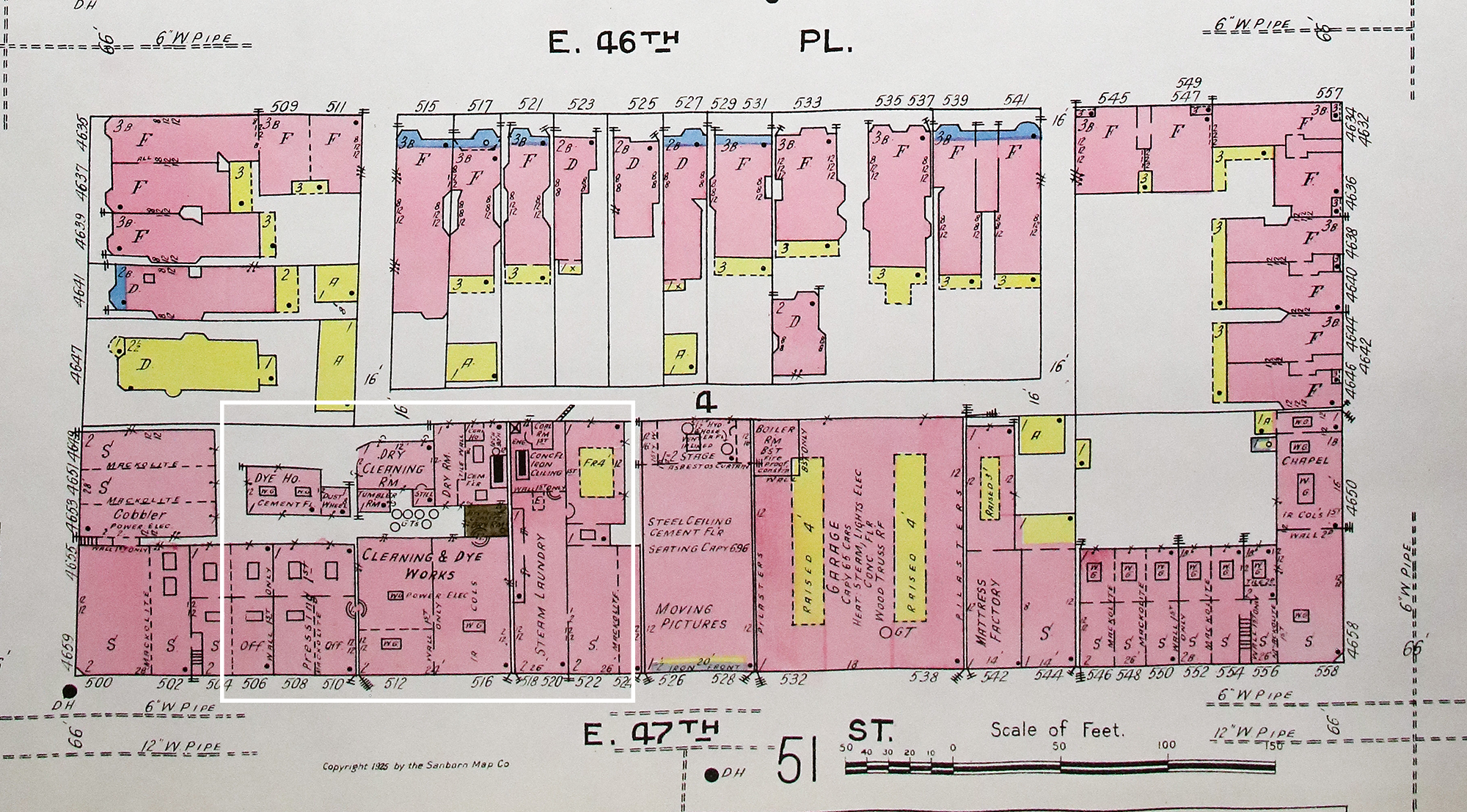

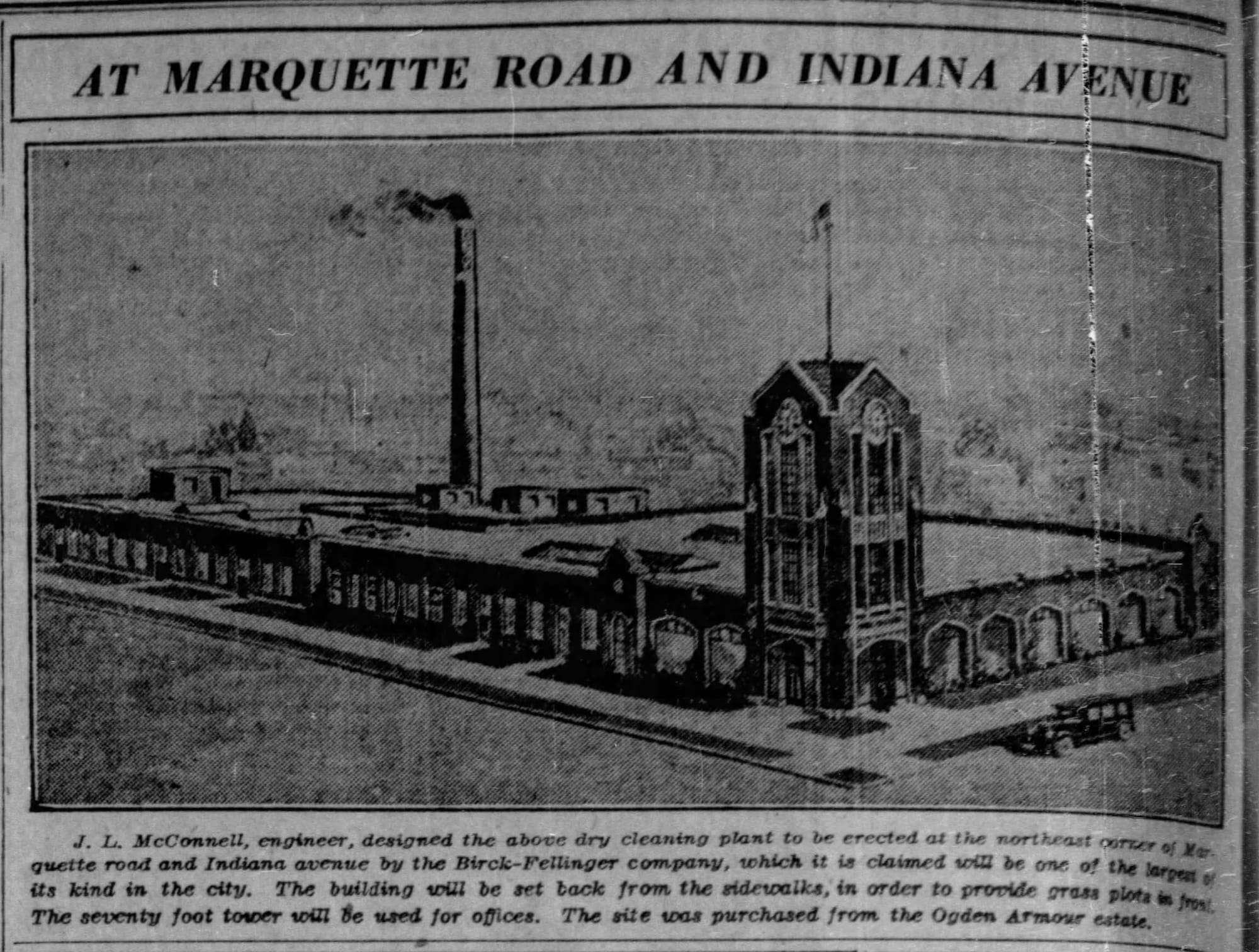

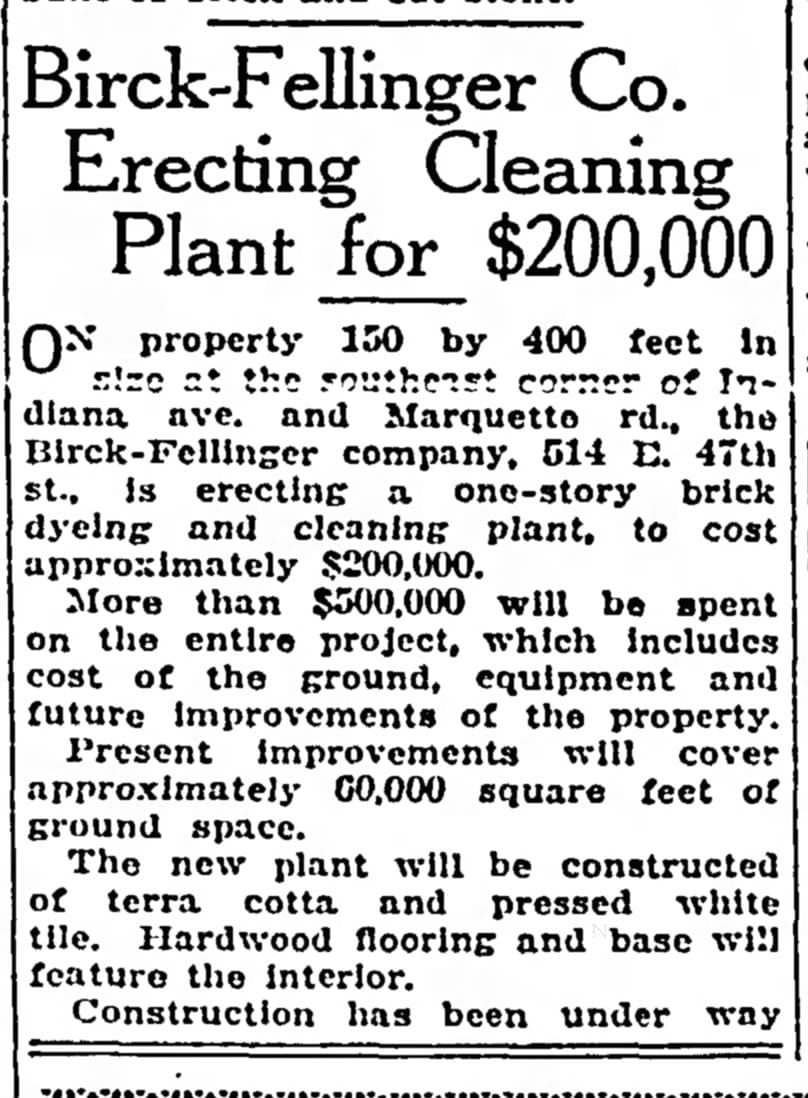

A successful South Side rug cleaning, dyeing, laundry, and dry cleaning establishment founded in 1898 by Robert M. Birck and Otto H. Fellinger, by the mid-1920s Birck-Fellinger had outgrown their hemmed-in location at 506 E. 47th Street. There was also probably an element of white flight as well, with that building squarely in Chicago’s Black Belt by the 1910s. For its new main plant and office, Birck-Fellinger bought a large greenfield site three miles south and hired J.L. McConnell to design one of the biggest industrial cleaning plants in the city.

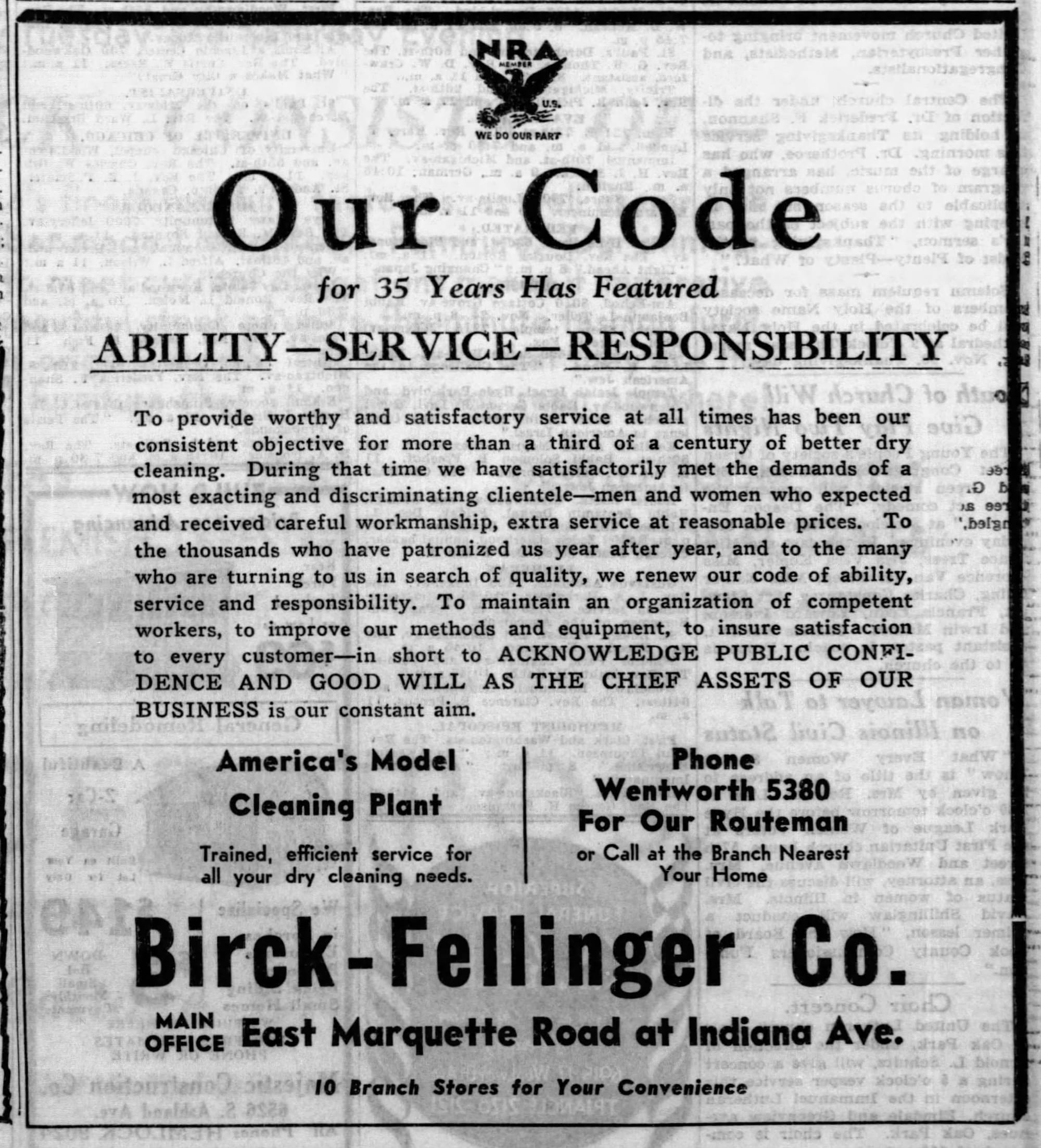

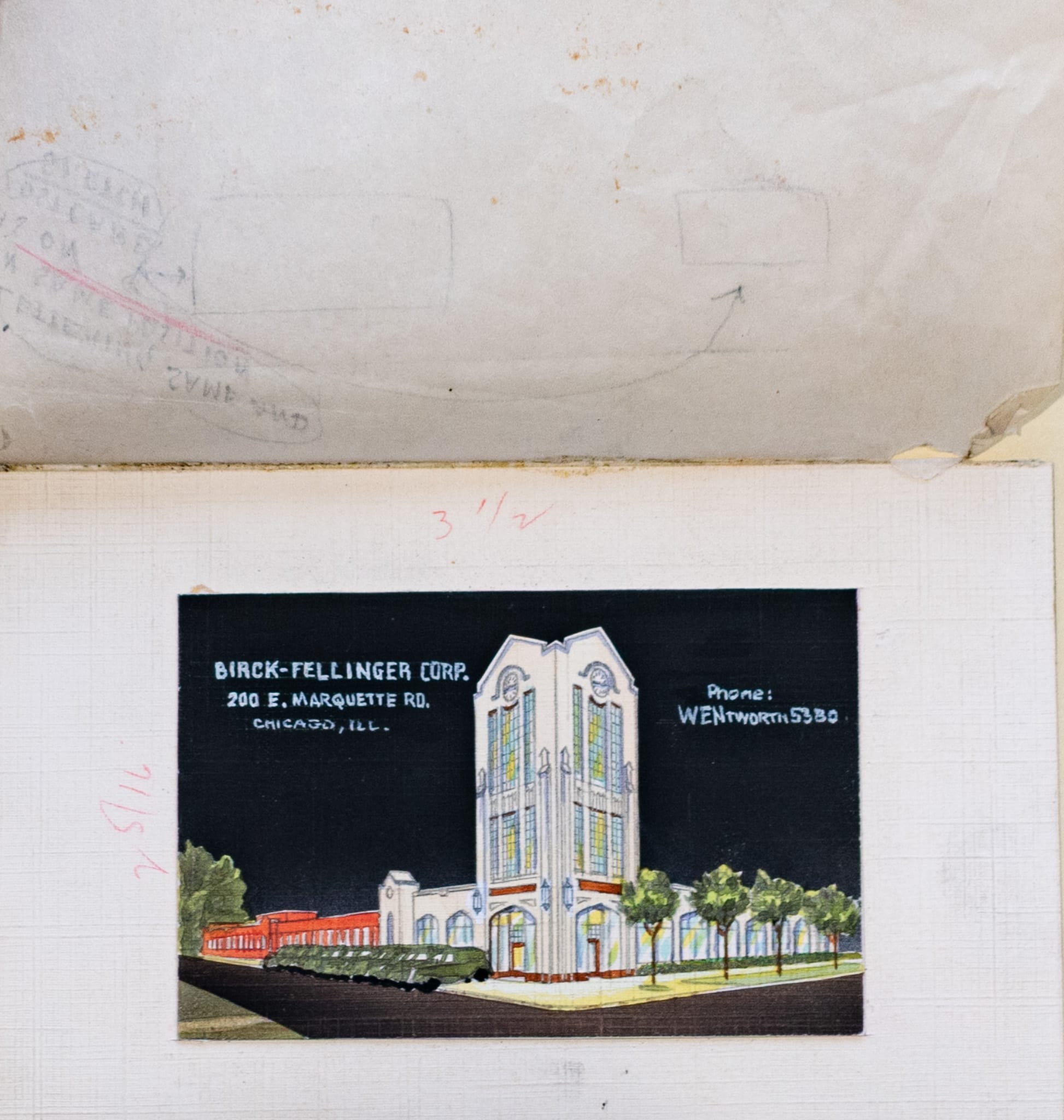

McConnell appears to have been more of an engineer than an architect, but his firm did design a clutch of industrial buildings around Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s (along with a stint as Chief of Construction & Utilities for the 1933 World’s Fair), so the Birck-Fellinger plant sits right in that portfolio. Marketed as "America’s Model Cleaning Plant", the company spent $3.75m in 2025 dollars building the facility—industrial Gothic clad in terracotta and white tile with terrazzo and hardwood floors. The building housed the company’s offices, pressing and laundry rooms, a dry cleaning operation, a rug and drapery cleaning department, and a cold storage area for furs.

Former Birck-Fellinger location, 1925 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map | Former Birck-Fellinger location on 47th Street, 2025 Google Streetview | 1927 rendering | 1928 article | 1928 ad | 1930, Seth Thomas Clock Company tower clock catalog, the Internet Archive | 1950 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map | 1950s interior photos, the National Cleaner and Dryer, 1956, the Internet Archive

The tower, decorated with a clock from the Seth Thomas Clock Company, topped out at 52 feet—industrial cleaning plants and laundries, with their smokestacks and water towers and need to reach customers, once played an influential role in Chicago’s neighborhood skylines.

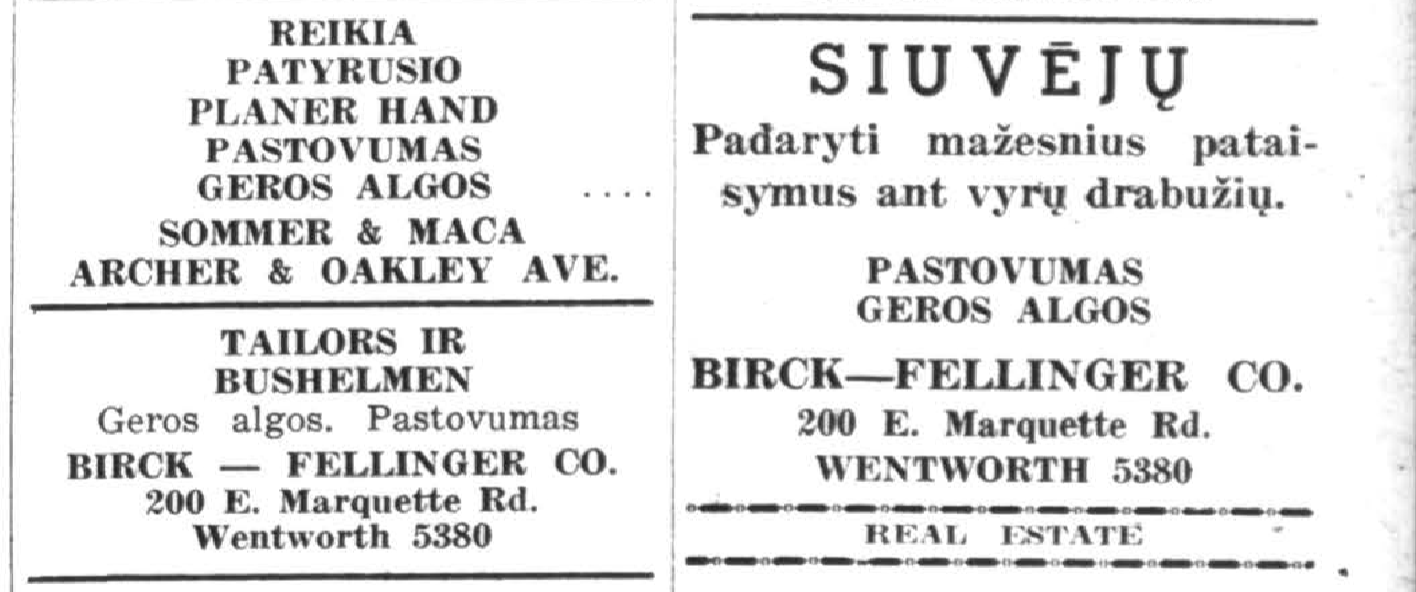

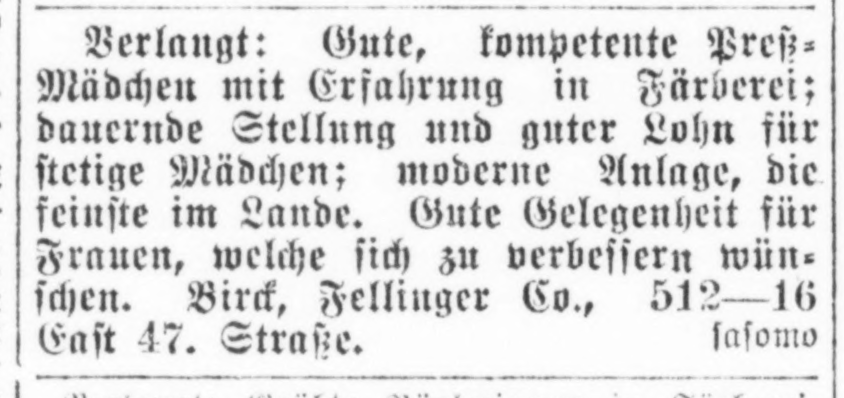

Birck-Fellinger survived the Great Depression—they were a member of the New Deal-era National Recovery Administration (the good NRA)—and continued growing in the 1940s and 1950s. Most dry cleaning plants in Chicago were racially integrated, and you can see Birck-Fellinger working to reach potential employees in the communities they lived in—the company ran help wanted ads in the Chicago Defender, one of the city’s African-American newspapers, but also in Draugas (Lithuanian) and Abendpost (German), amongst others. A 1947 job posting for a presser advertised wages of $2 an hour, the equivalent of $28 an hour today.

1933 ad with the National Recovery Administration eagle on it in the Chicago Tribune | 1944 ad in the Chicago Defender | 1948 ad in Draugas | 1916 ad in Abendpost, the Internet Archive | 1947 ad, $2 an hour, the Chicago Tribune

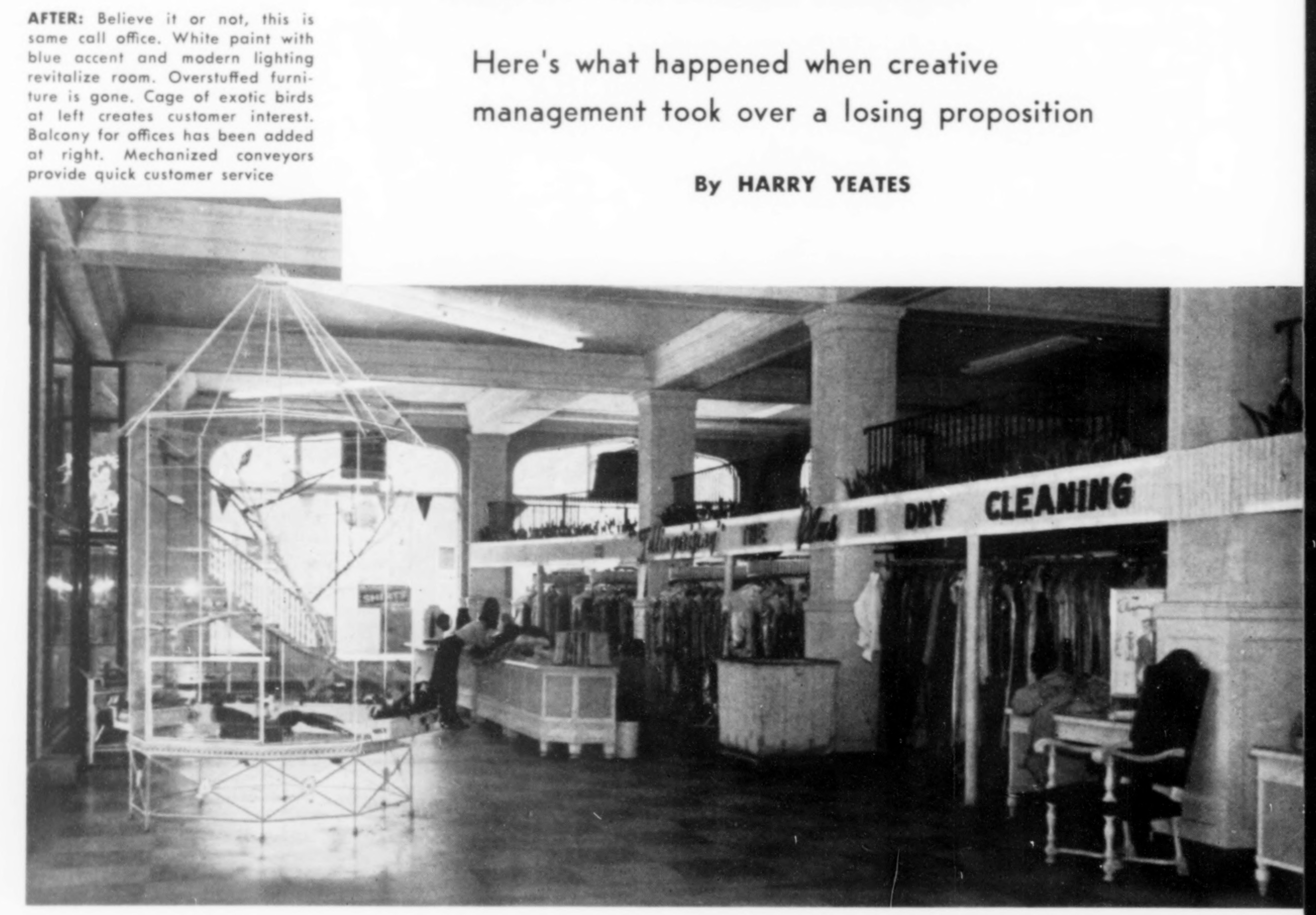

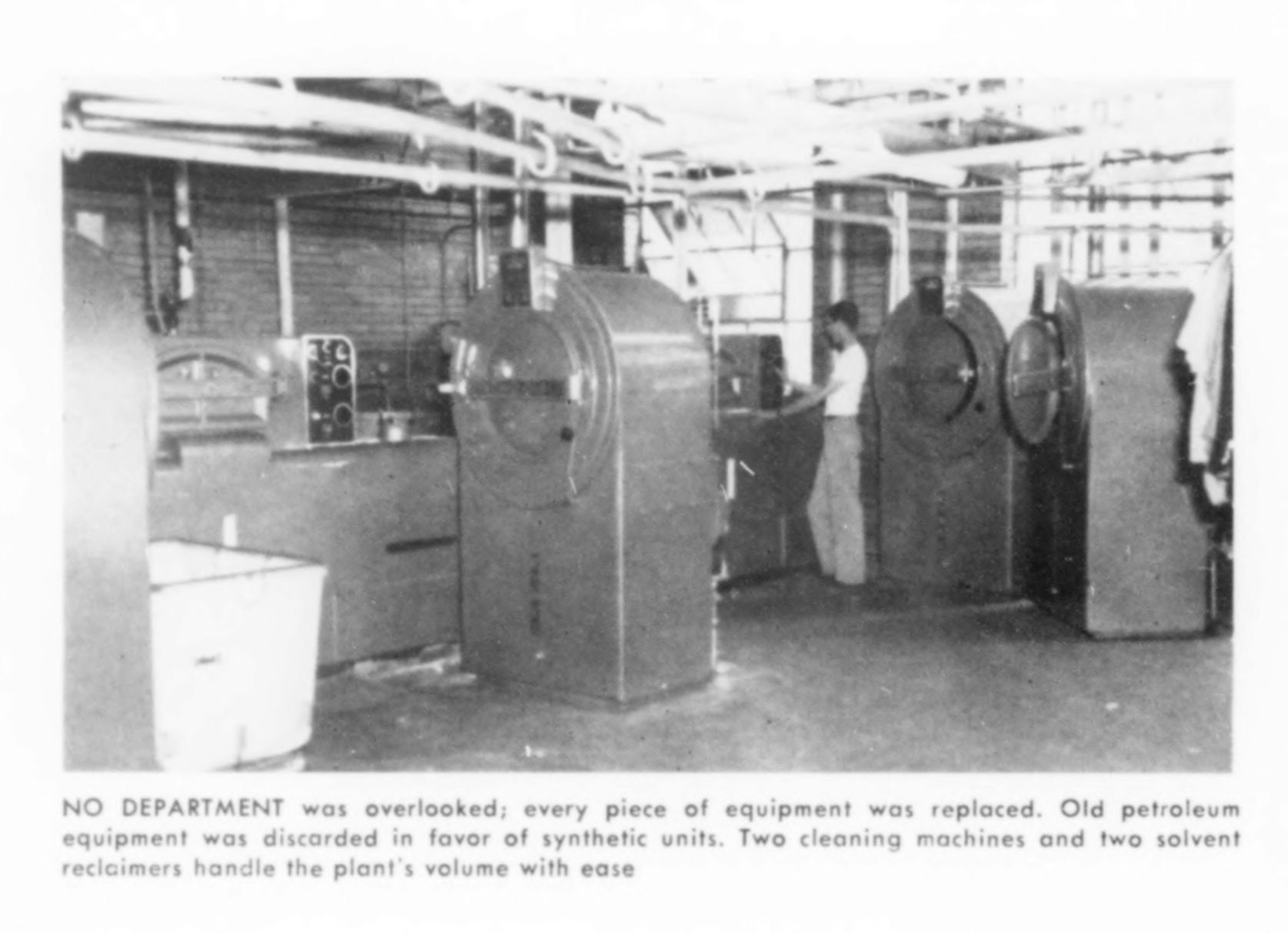

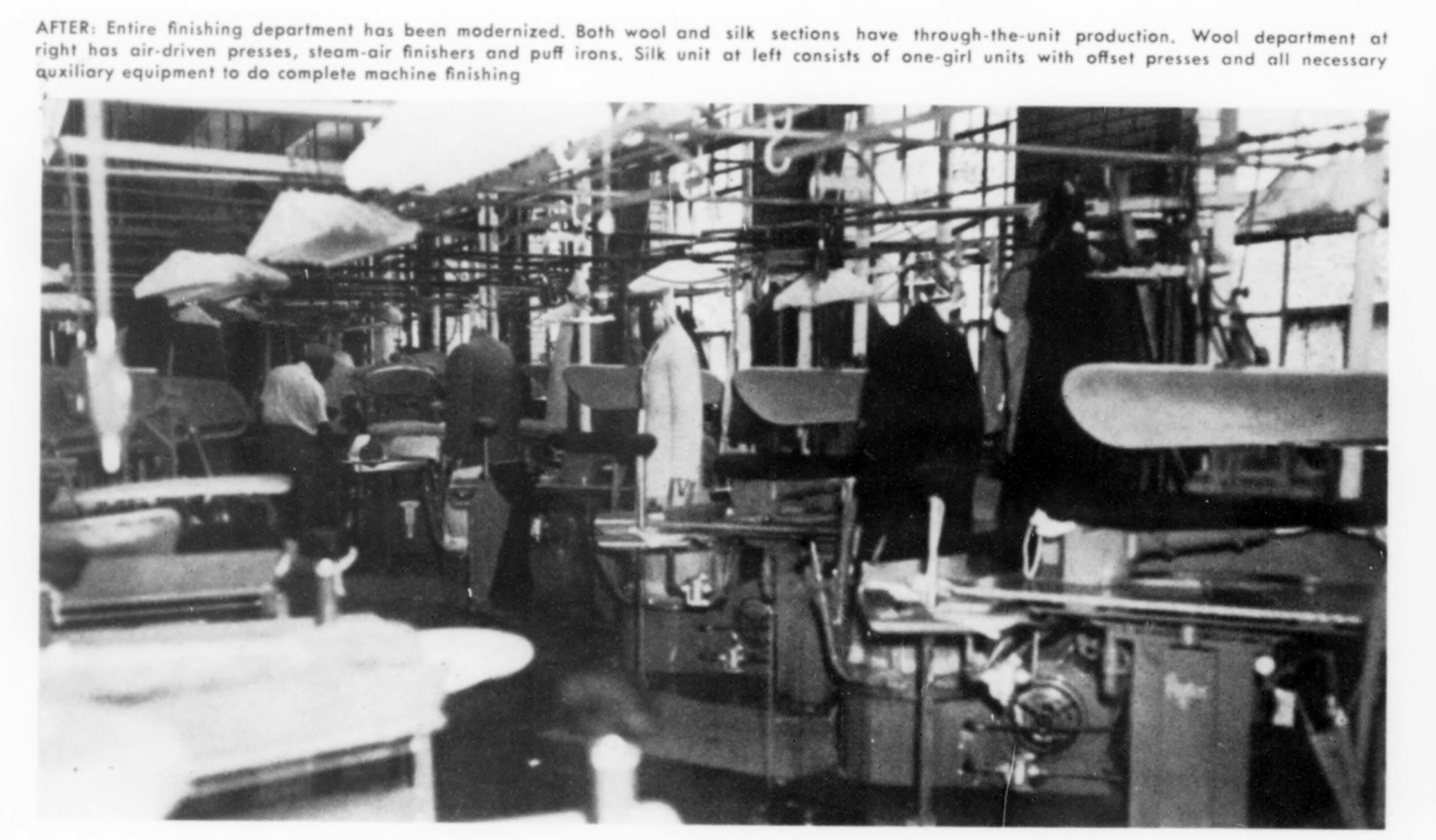

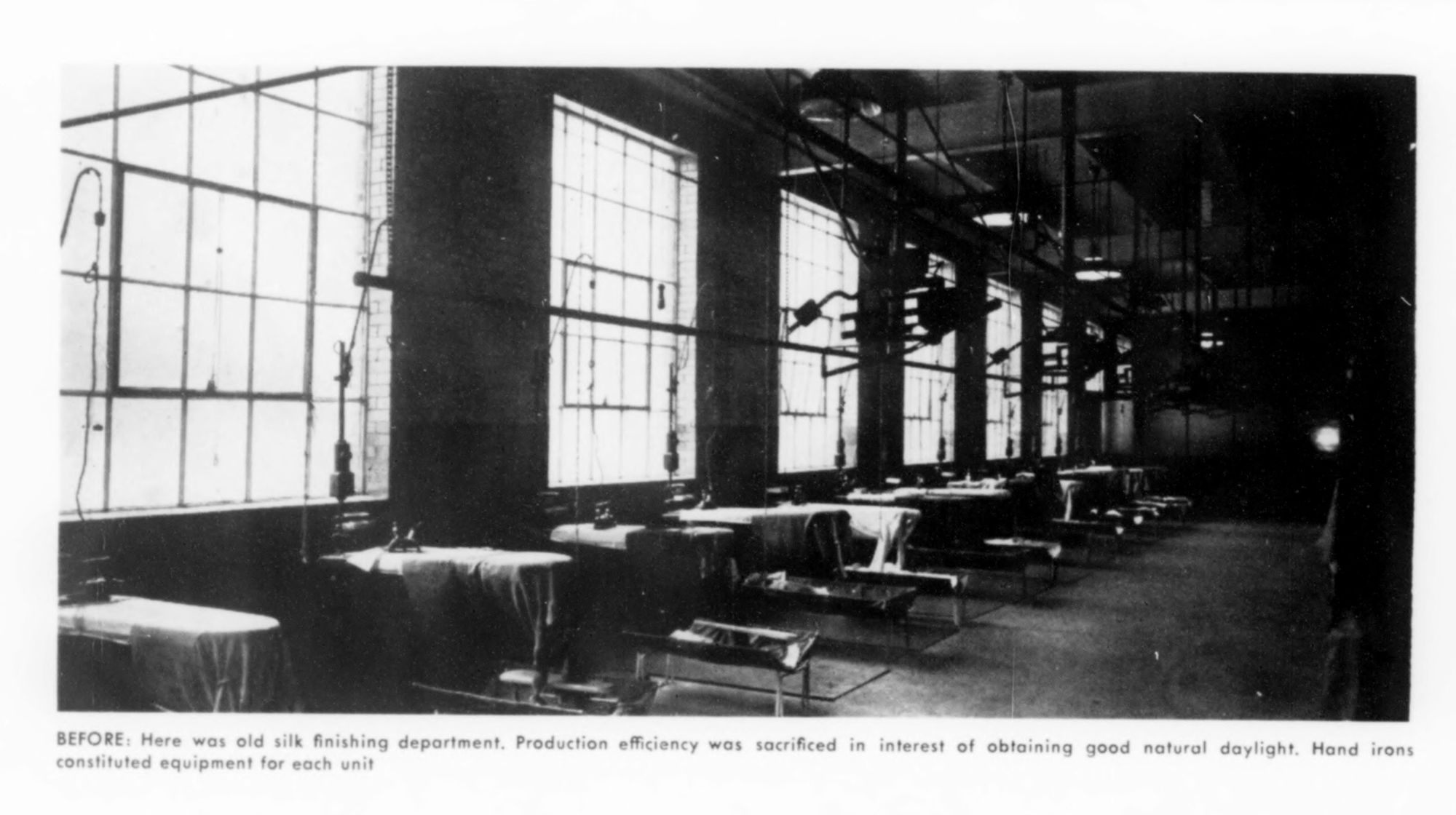

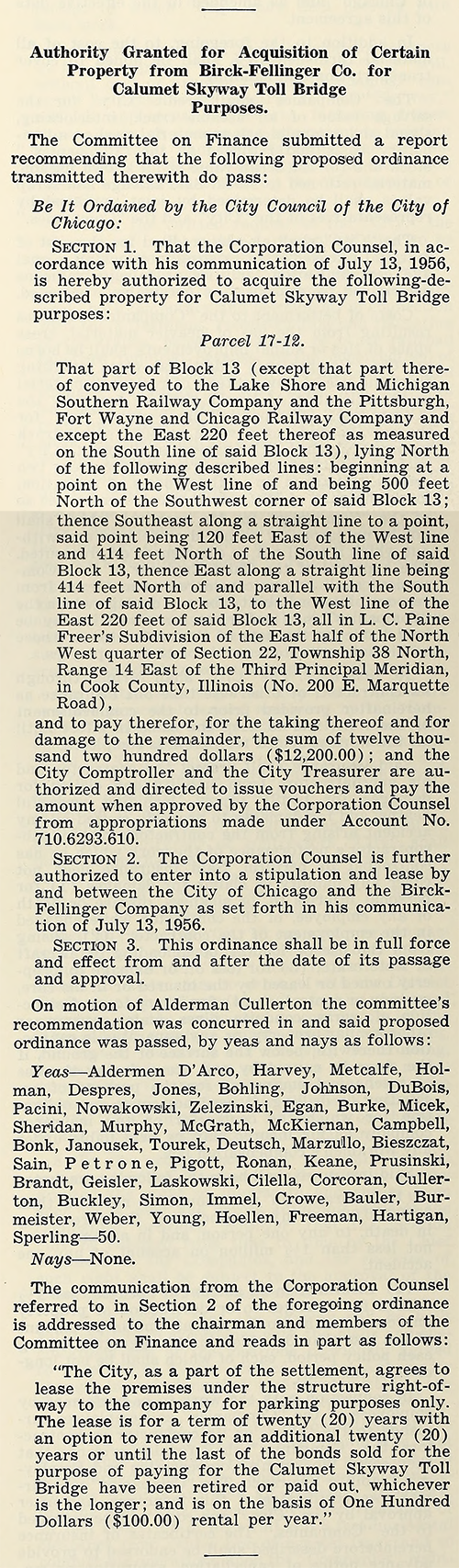

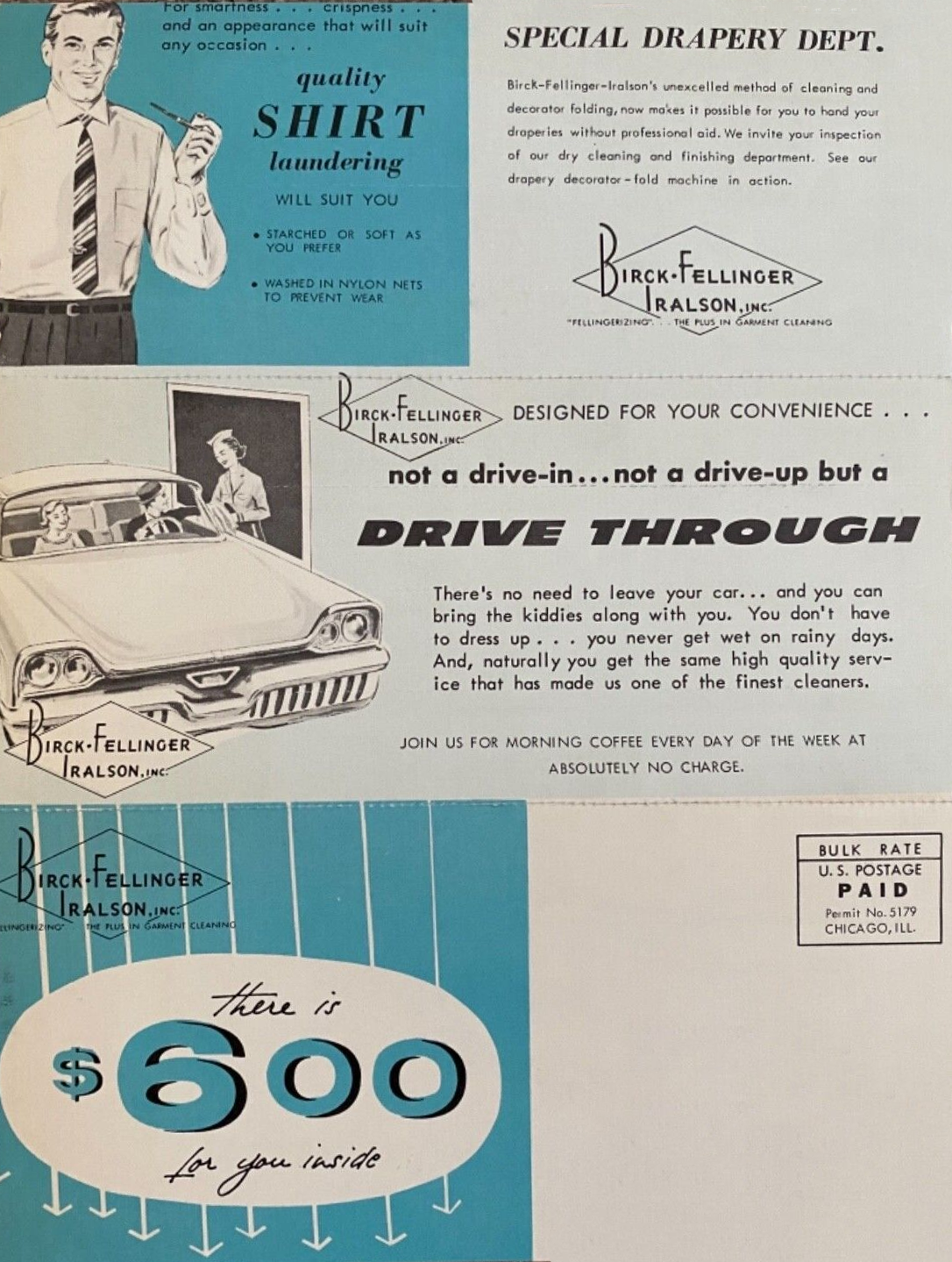

By the 1950s, Birck-Fellinger’s annual revenue exceeded $500k ($6m in 2025 dollars), and in 1955 C.A. Boushelle & Son, another rug cleaner, bought the company. The new owners quickly launched a renovation of the aging plant, turning the main office area (by the windows along Marquette Road) into a drive-through, cutting an opening into the base of the tower and a curb-cut onto Indiana Ave. They also replaced much of the equipment, reconfiguring the workflows, and…added a big bird cage with exotic birds to “create customer interest”? 1956 was a time of change in both the customer-facing and back-of-house parts of the Birck-Fellinger complex—the company sold a sliver of land at the back of the plant to the city for the Skyway Toll Bridge.

1955, Boushelle purchases Birck-Fellinger | The 1956 renovation in the National Cleaner and Dryer, the Internet Archive | 1956, Chicago City Council buys a portion of the site for the Skyway, the Internet Archive | 1958 open house ad | 1958 Boushelle Ad with the building visible

An open house to celebrate the refreshed cleaning plant featured pioneering WGES DJ Sam Evans, Illinois State Senator James Y. Carter, and 6th Ward Alderman Sydney Jones Jr. In 1958, DuPont commissioned a 12-minute-long color video, “Two Hour Miracle” that was shot here by Fred Niles Productions (I checked if the Hagley Library—which holds much of DuPont’s archives–had it, but it appears they only have the script). The renewed plant was once again a bit of a boast.

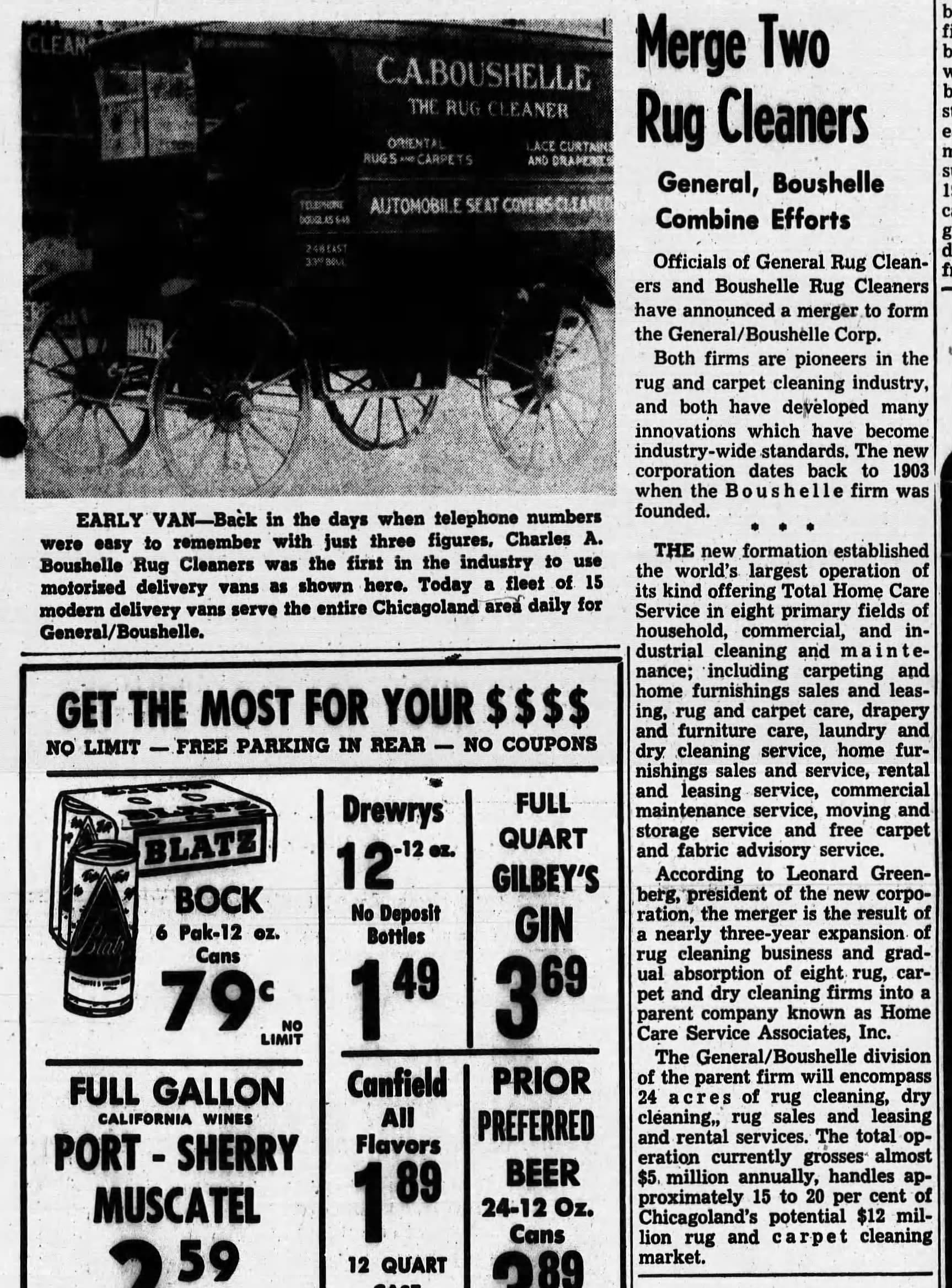

Boushelle merged with General Rug Cleaners in 1965 (the merged company’s jingle, “HUdson 3-2700” appears to have become a minor earworm in 1970s Chicagoland). This plant continued cleaning rugs and drapes and doing dry cleaning, but with some minor changes to names and organizational structure: Birck Fellinger Iralson, then David Webber Birck Fellinger (but always as a division of General Boushelle).

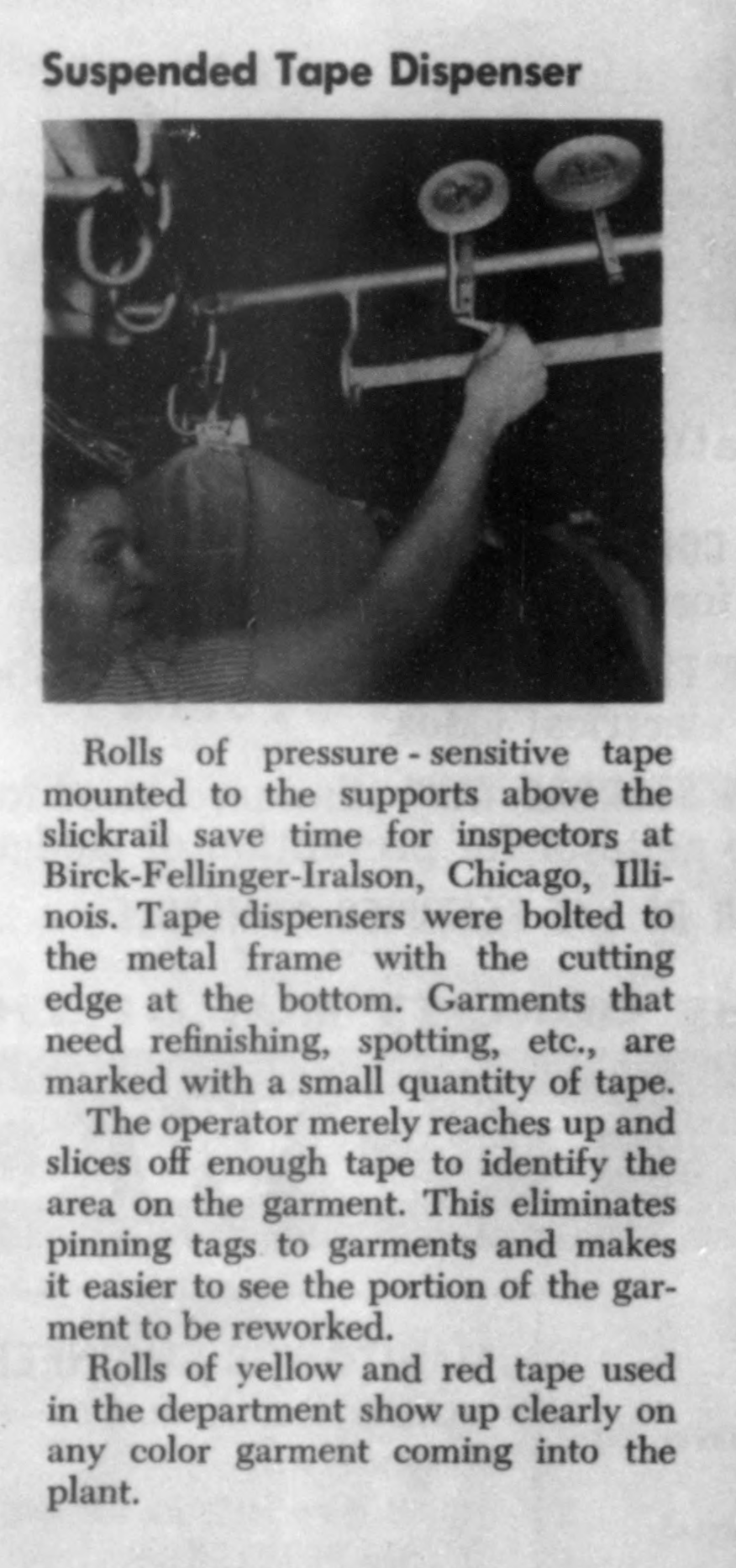

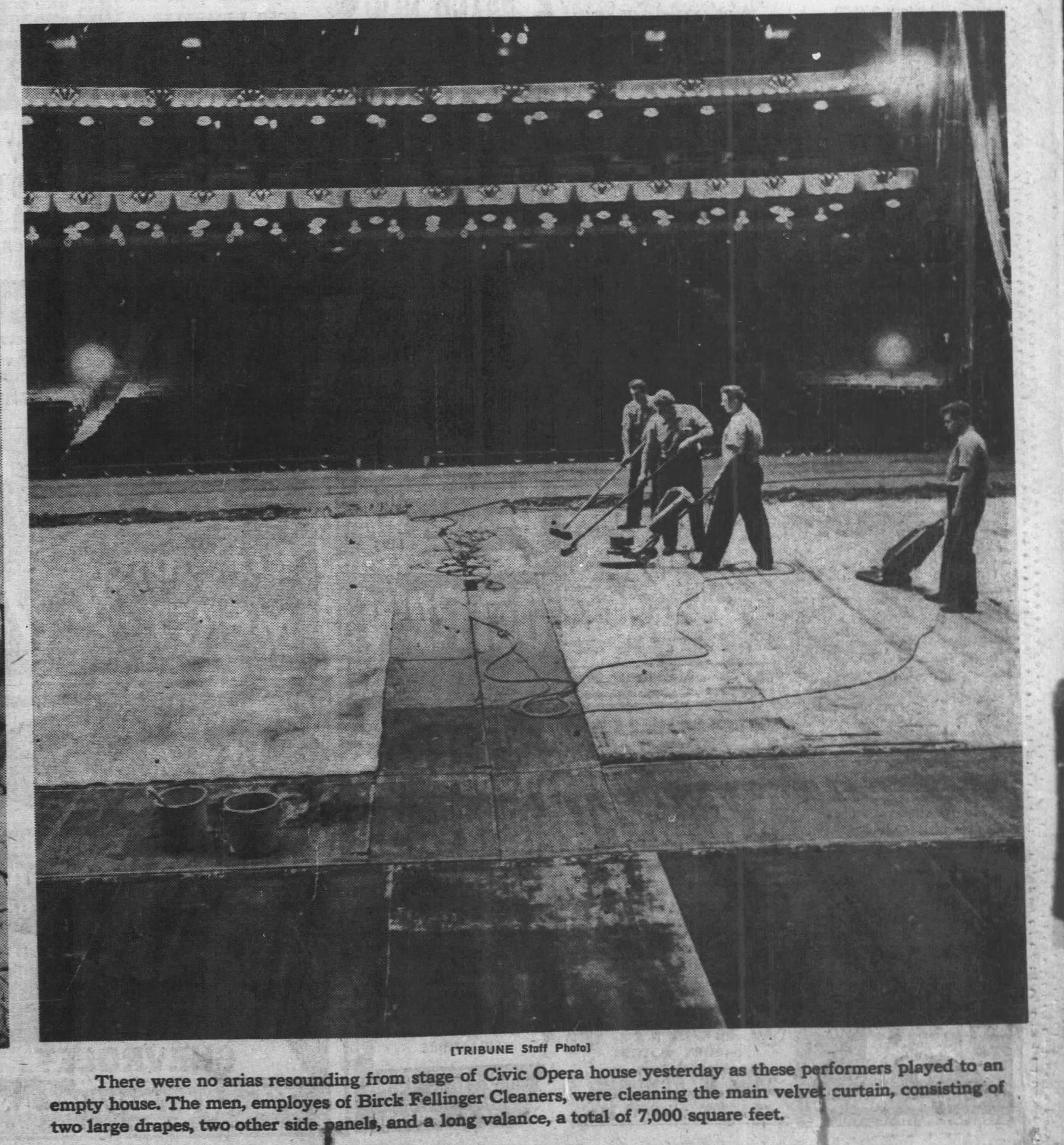

the drive through in the Chicago Defender, 1956 | 1958, plant using a suspended tape dispenser, the National Cleaner and Dryer, the Internet Archive | 1961 office view, the Laundry Journal, the Internet Archive | 1960s matchbook and coupon books | 1965 article on the formation of General Boushelle | 1965, Birck-Fellinger cleaners clean the Civic Opera House curtain | 1970s, Illinois State Historic Preservation Office

Do Americans have fewer rugs and drapes than they used to? At the very least, the rug cleaning industry doesn’t have the visibility it once had (see also the disappearance of the Magikist signs around Chicago), and it appears that General Boushelle and their Birck-Fellinger division vacated this building by the late 1970s.

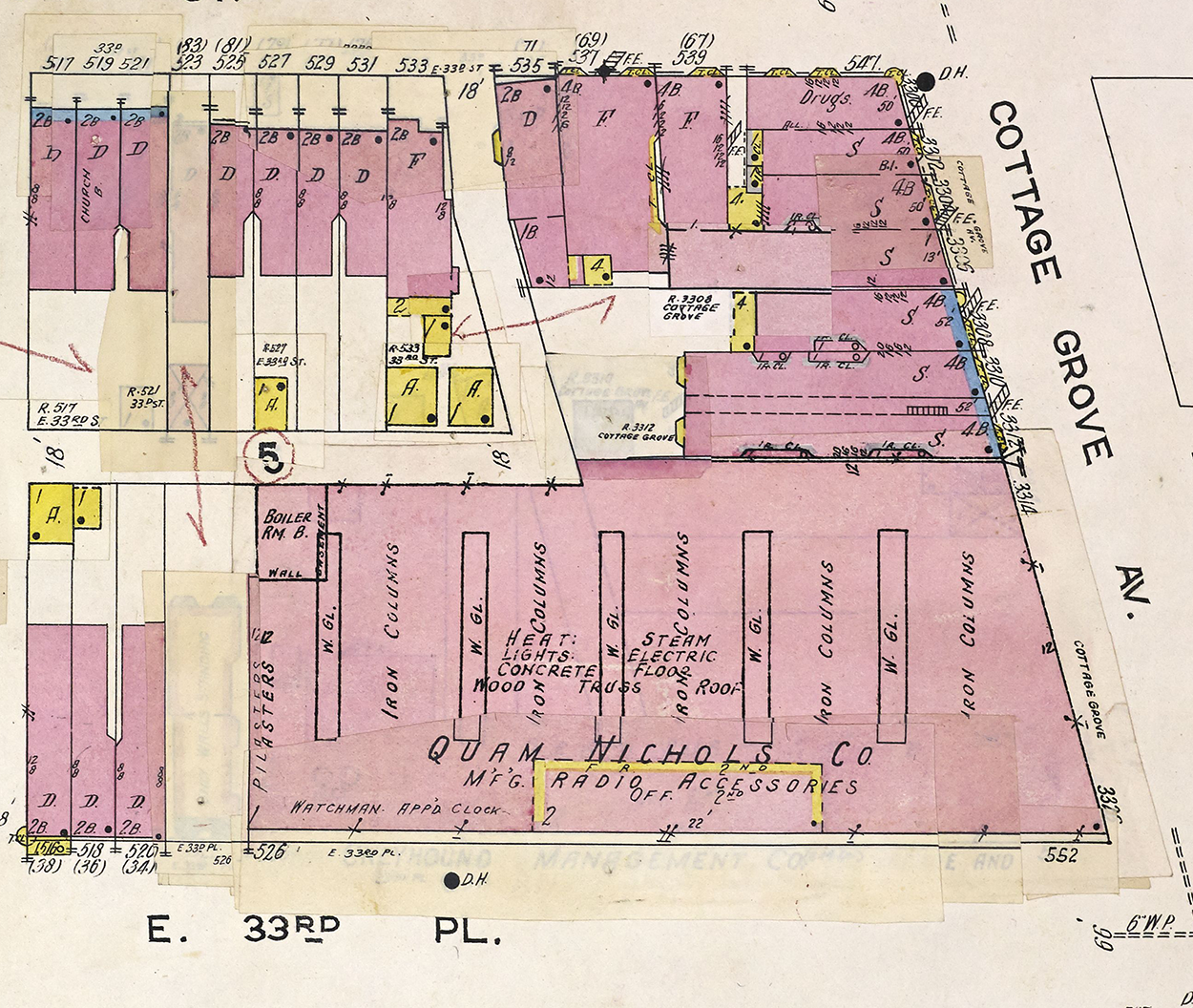

Quam Nichols, a loudspeaker manufacturing company (and like Birck-Fellinger, one long based in the Black Belt at 33rd & Cottage Grove), opened their new plant next door to Birck-Fellinger in 1953. With industrial cleaning plants closing across Chicago, it looks like Quam Nichols took over their next door neighbor sometime in the 1980s. From what I can tell through shadows on aerial photos, I think the tower was removed between 1988 and 1990—presumably the cost of maintenance combined with advances in water pressure making tanks like this a little redundant, along with a reduced need to advertise to a local clientele in the loudspeaker business.

Just about all the glamor of McConnell’s model cleaning plant is gone, but you know what—after 95 years Quam Nichols is still manufacturing in Chicago out of this location, so that’s something.

Aerials, 1938-2010

Production Files

Further reading:

- Full article on the 1956 renovation in the National Cleaner and Dryer

- "Negro-White Relations in a Chicago Dry Cleaning Plant", University of Chicago masters dissertation by Jack Fooden

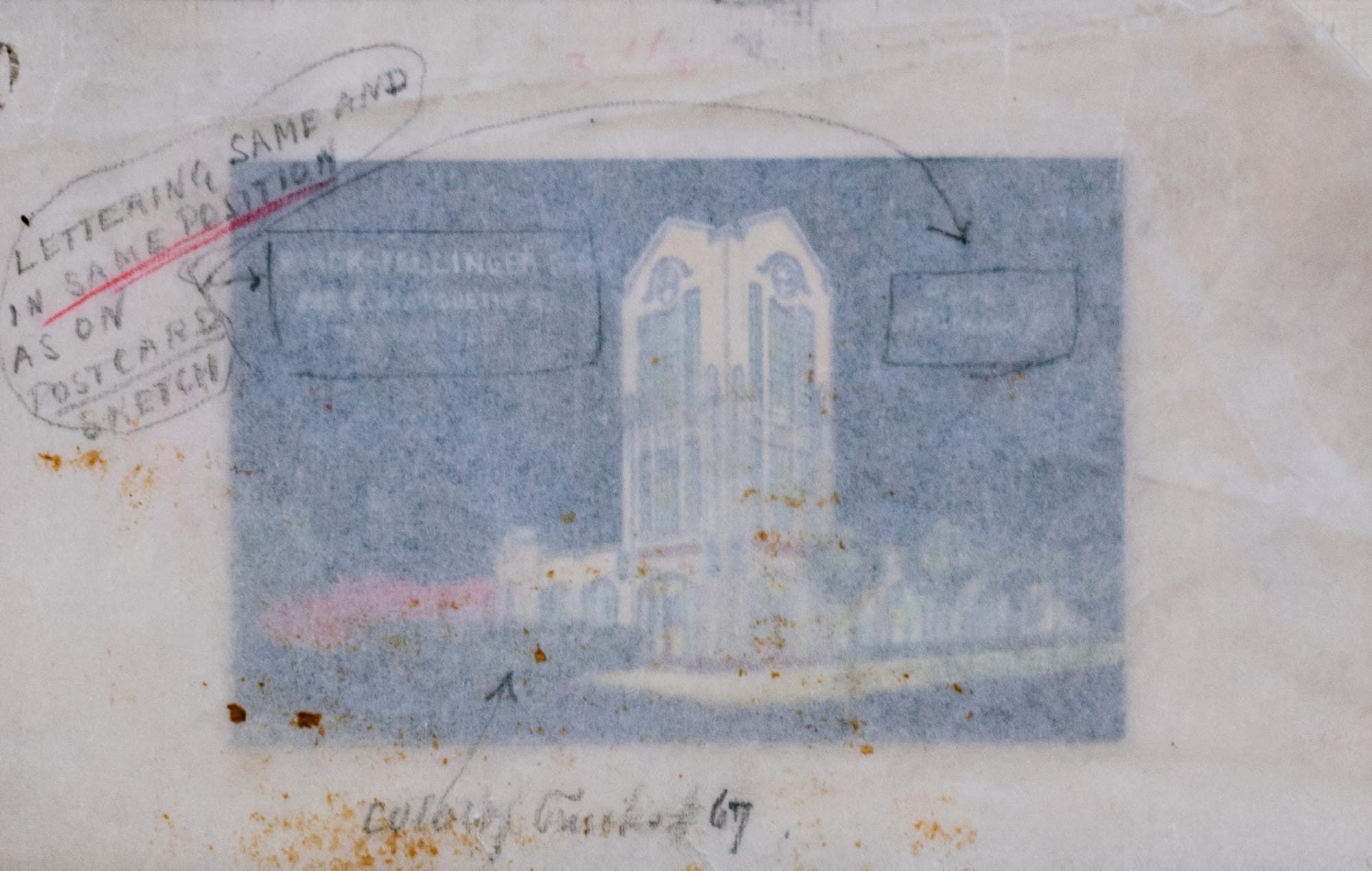

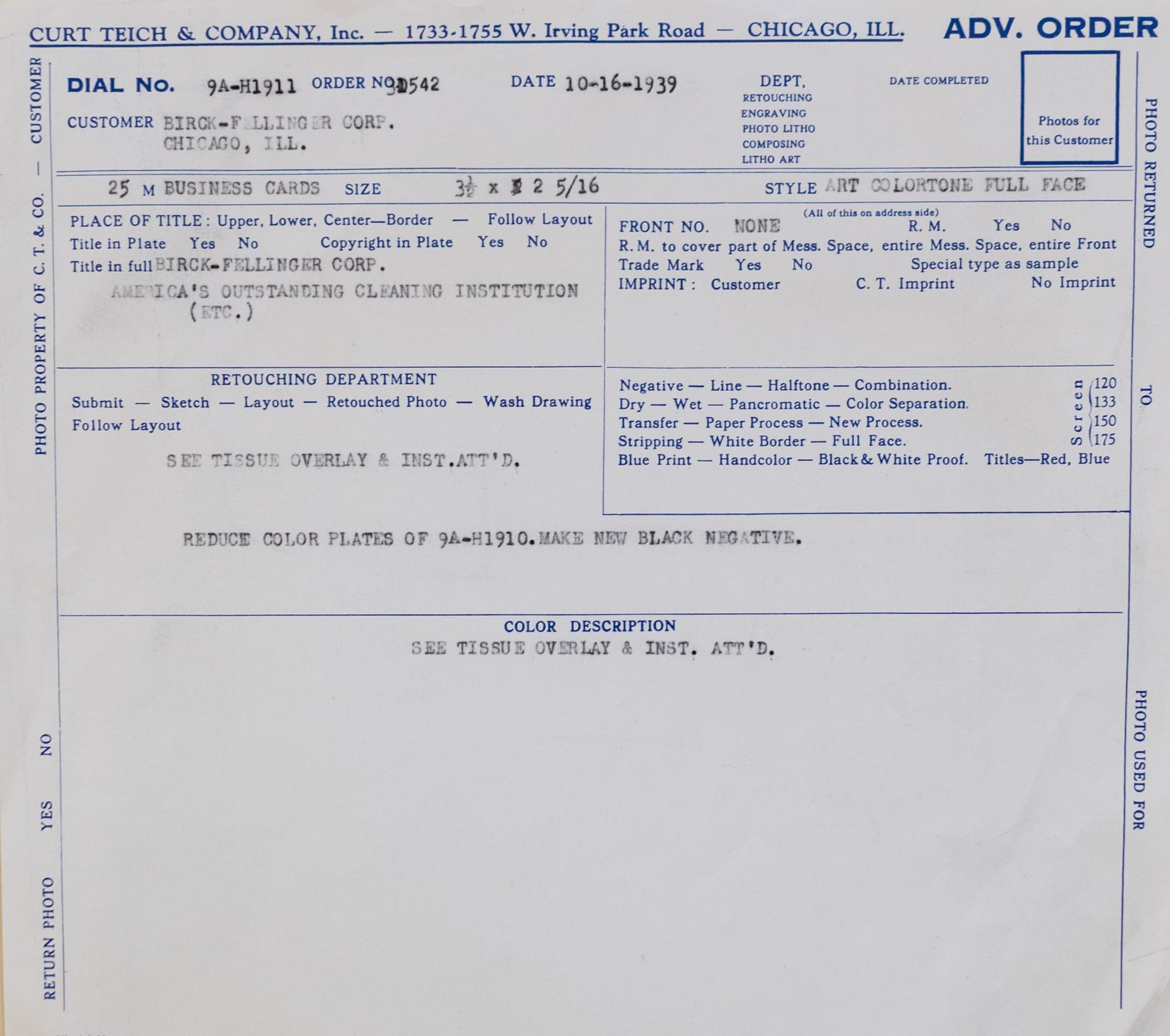

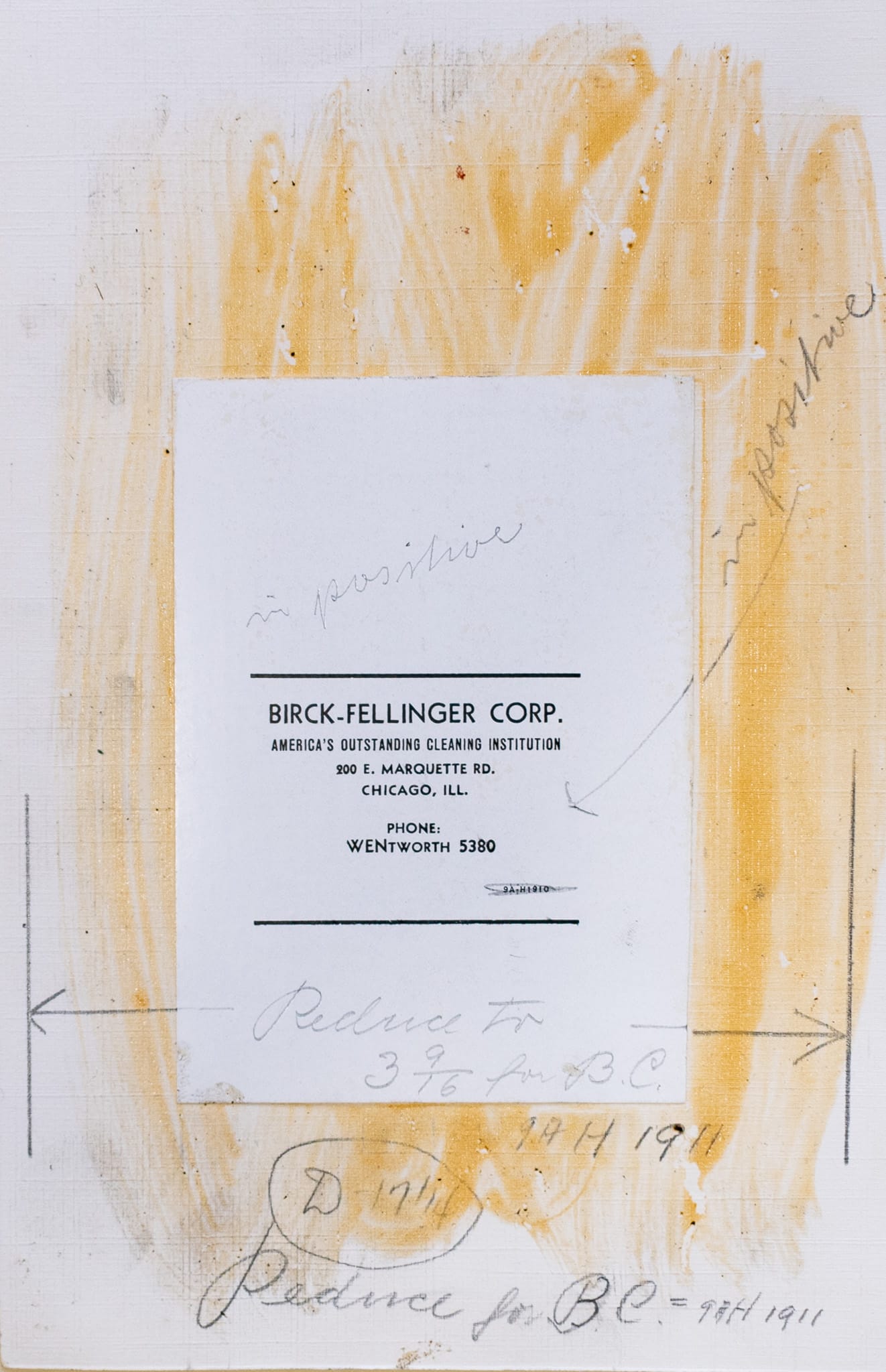

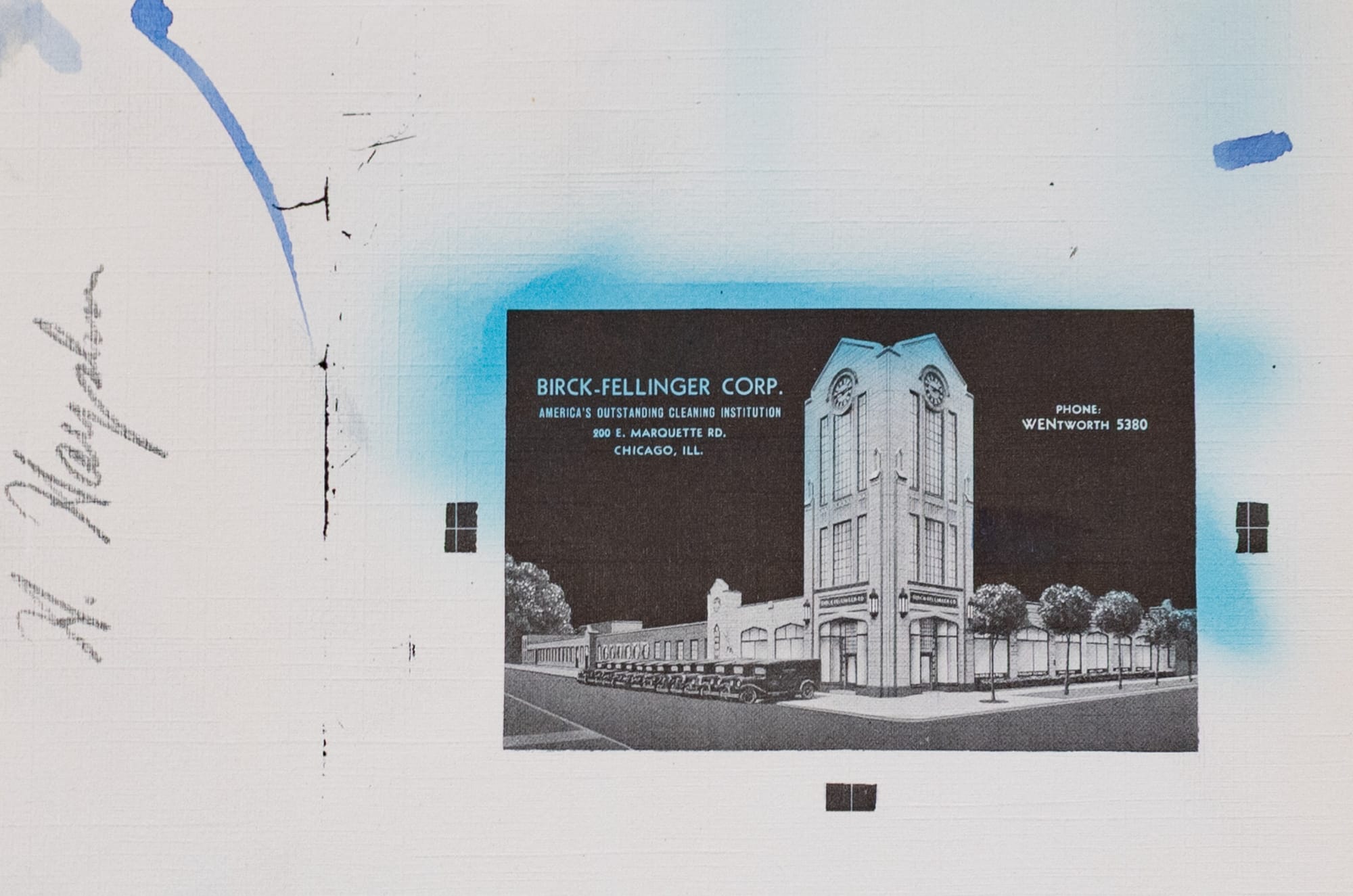

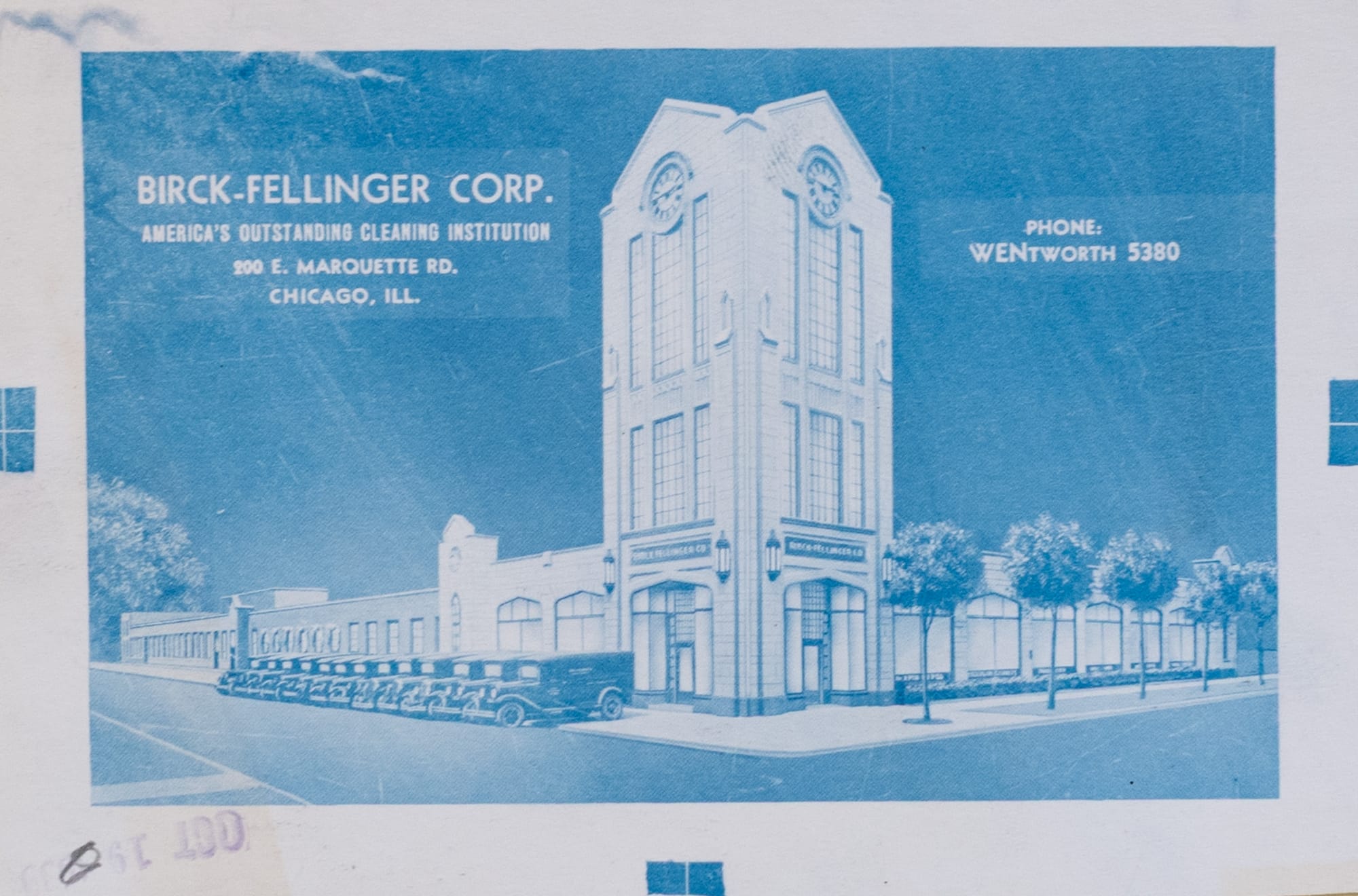

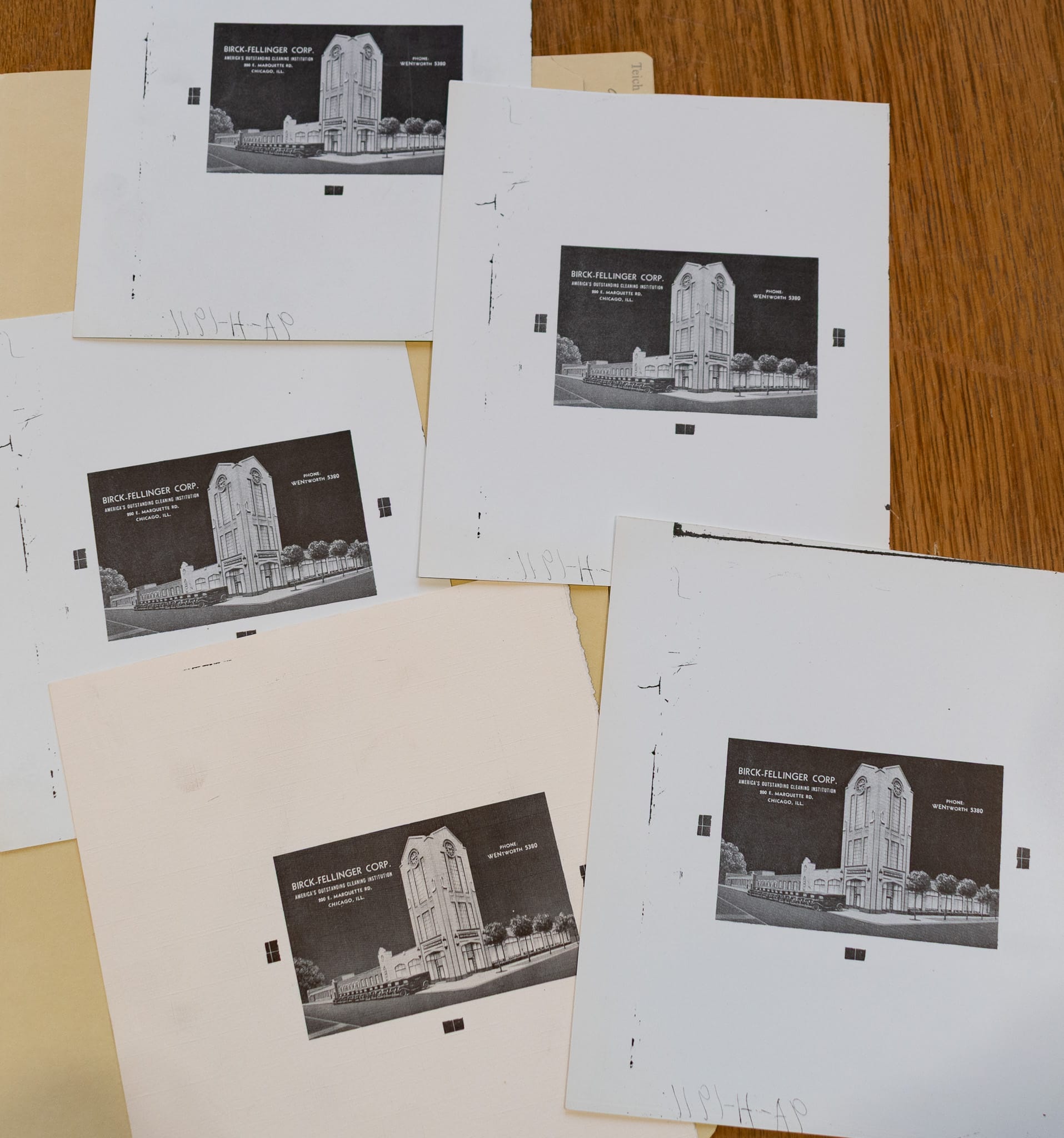

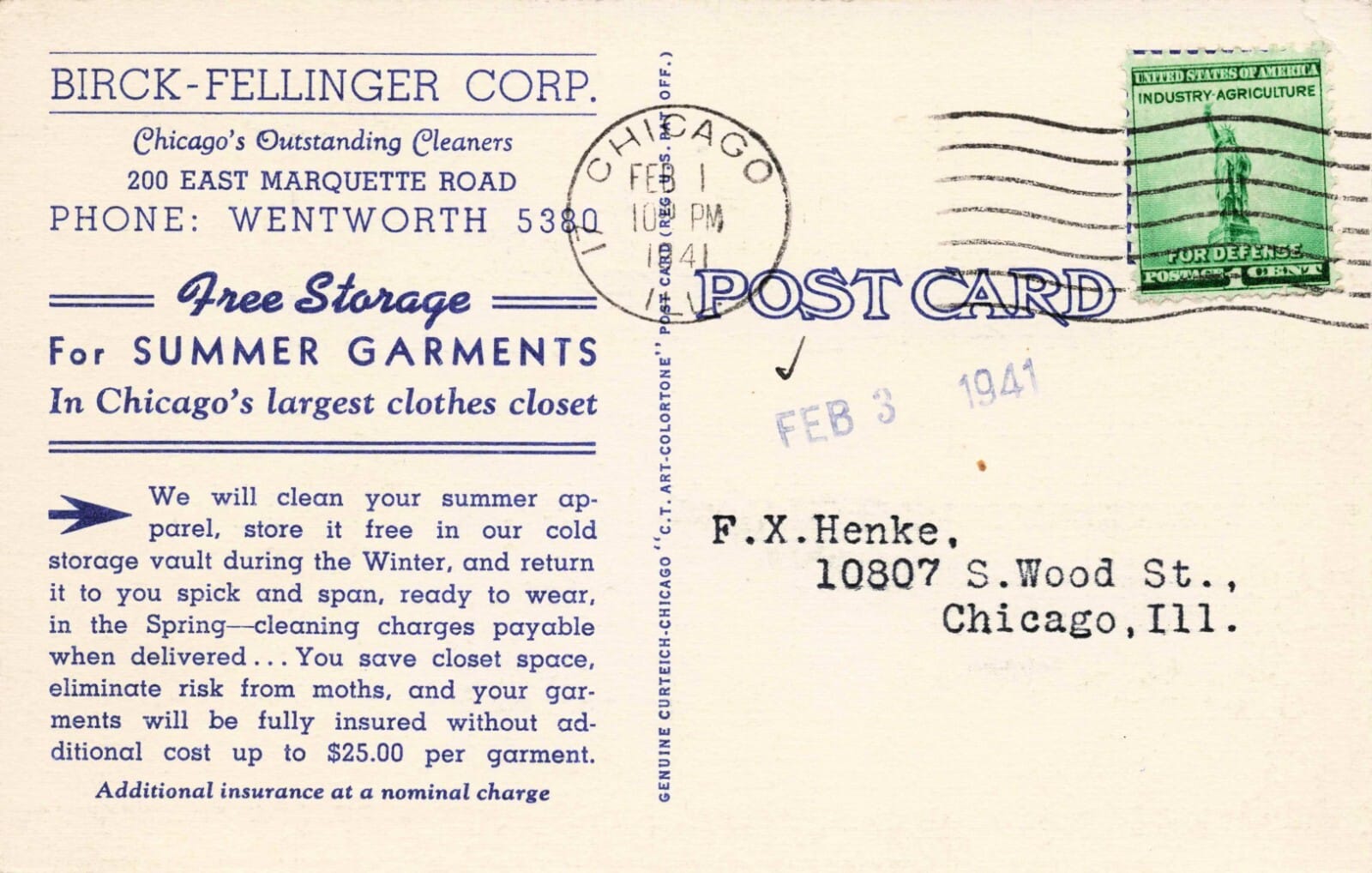

The actual production file at the Newberry was extremely rich for this one, full of tracing paper tissue overlays, retouching instructions, and mock-ups. From my understanding of the process, after a customer inquired about publishing a postcard, Curt Teich & Co. would come back with a roughly illustrated design like the below, with a little back-and-forth on style, coloring, and text.

Once the design was agreed on, they finalized it with an order, sending it on for full-scale retouching, production, and printing.

Retouching here included instructions on the color and material of the building, removing the smokestack, and adding small red neon signs along the windows.

Plus they had to add and position all the text for the front and back of the postcard.

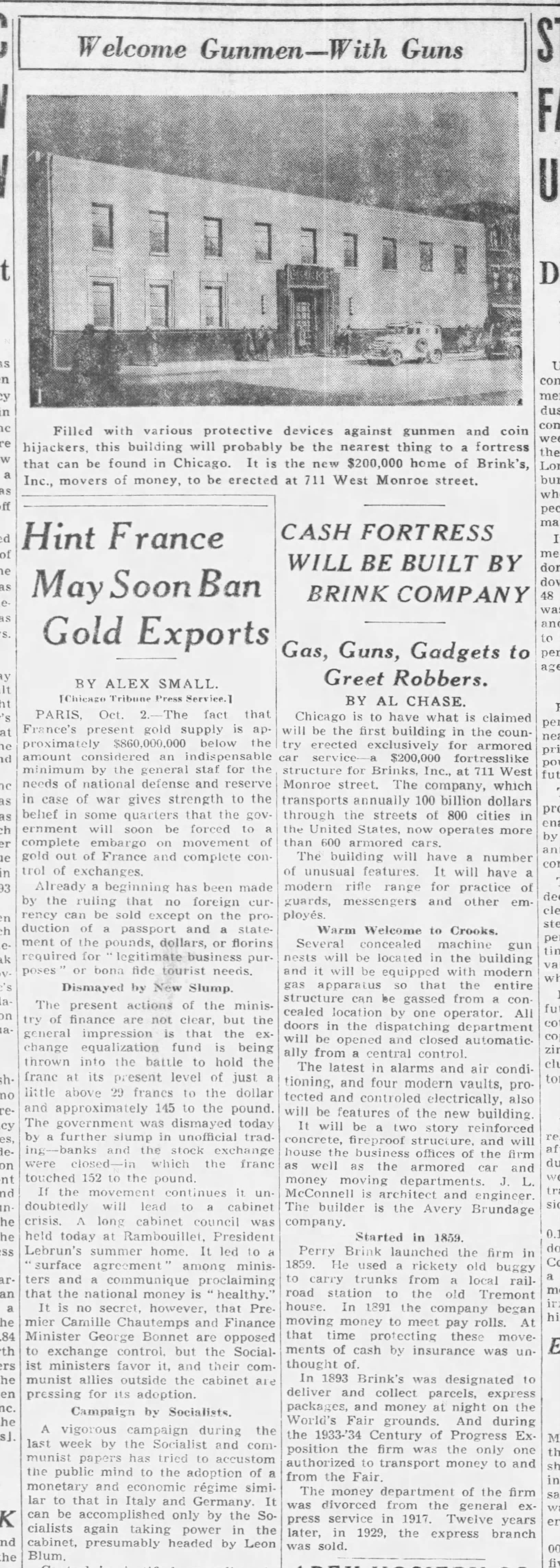

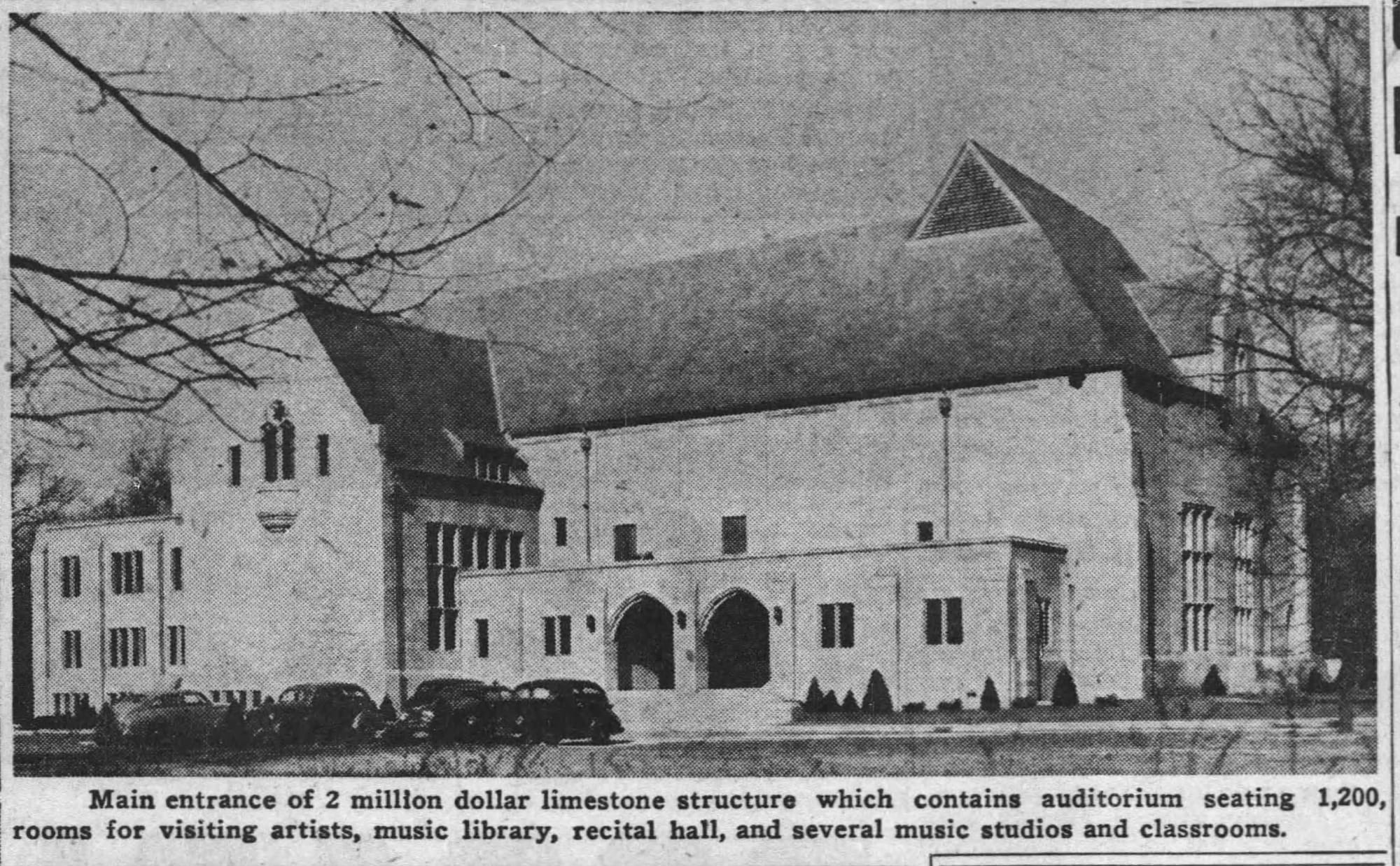

The architect, J.L. McConnell, was pretty obscure (and definitely more of an engineer), but there are a surprising handful of extent McConnell buildings around the city, including the Brinks Building on Monroe (1938, now the Archdiocese Of Chicago Archives & Records Center), Bates Valve Bag Co. (8240 S Chicago Ave), 1009 W Lake (fish smoking and sausage factory, extent), 322 S Green, and the Dominican University Performing Arts Center.

(that athletic club in Bronzeville was unfortunately never built as far as I can tell, although given the location it would've been demolished anyway)

1937, J.L. McConnell design the Brinks Building on Monroe | 2021 Google Streetview of the former Brinks building | 1923, McConnell designs an athletic club | 1921, McConnell designs an auto body factory on Green | 2019 Google Streetview of the building | 2018 Google Streetview of the McConnell-designed Bates Valve Bag Co. building on South Chicago Ave. | 2025 Google Streetview of the McConnell-designed building at 1009 W. Lake | 1952, McConnell's firm is the associate architect for Dominican University's Performing Arts Center

Quam Nichols was founded in 1930, briefly operated out of 1410 W. 59th in Englewood, then spent two decades at 33rd & Cottage Grove before building their facility here in 1952-1953.

1930, Quam Nichols moves to a site on Cottage Grove, Steel, the Internet Archive | Quam Nichols facility on Cottage Grove, 1950 Sanborn Fire Insurance map | new building on Marquette Road, 1953, Electrical Manufacturing, the Internet Archive | 1953, Illinois Business Review, the Internet Archive | 2025 Google Streetview

These were some of the leaders of Birck-Fellinger and General Boushelle.

Stanley Birck on Moth Seal Storage Bags in the National Cleaner and Dryer, 1955, the Internet Archive | Boushelle president Cecil Treadway filming a Birck-Fellinger ad, the National Cleaner and Dryer, 1956, the Internet Archive

A bunch of help wanted ads for various roles—that wool spotter ad from 1969 offering $130 a week (I think) would work out to $59k a year today.

1929, hat maker wanted | 1939, spotters and pressers wanted | 1943, night watchman wanted | 1943, shipping girls wanted | 1943, office and counter girls wanted | 1944, neat woman wanted | 1945, dyer wanted | 1953, routeman wanted | 1969, wool spotter wanted

And then some other regular ads.

1928 ad | 1929 fur storage ad | 1939 rug cleaning ad | 1940 cold storage ad | 1942 ad | 1956 ad in the Chicago Defender | 1956 drive-in ad | 1958 ad | 1961 ad

The aerials that went into making that animation.

1938 aerial, Illinois State Geological Survey | 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995 aerials, Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning | 2010 Google Earth

A few more random articles and ads:

- After completing this plant, Birck-Fellinger put their old location on 47th up for sale. Then, in 1931, tried to sell their other two branches in Black-majority neighborhoods.

- The office space in the tower was briefly used as the office for the leadership of the Greater South Side Chamber of Commerce.

1928 for sale ad | 1931 branches for sale | 1930, Greater South Side Chamber of Commerce office article | 1956 Bud Billiken Day ad | 1958 and 1964 articles about Boushelle taking over and being big | 1977 unclaimed fur sale ad

This is where I took the photo from.

Member discussion: