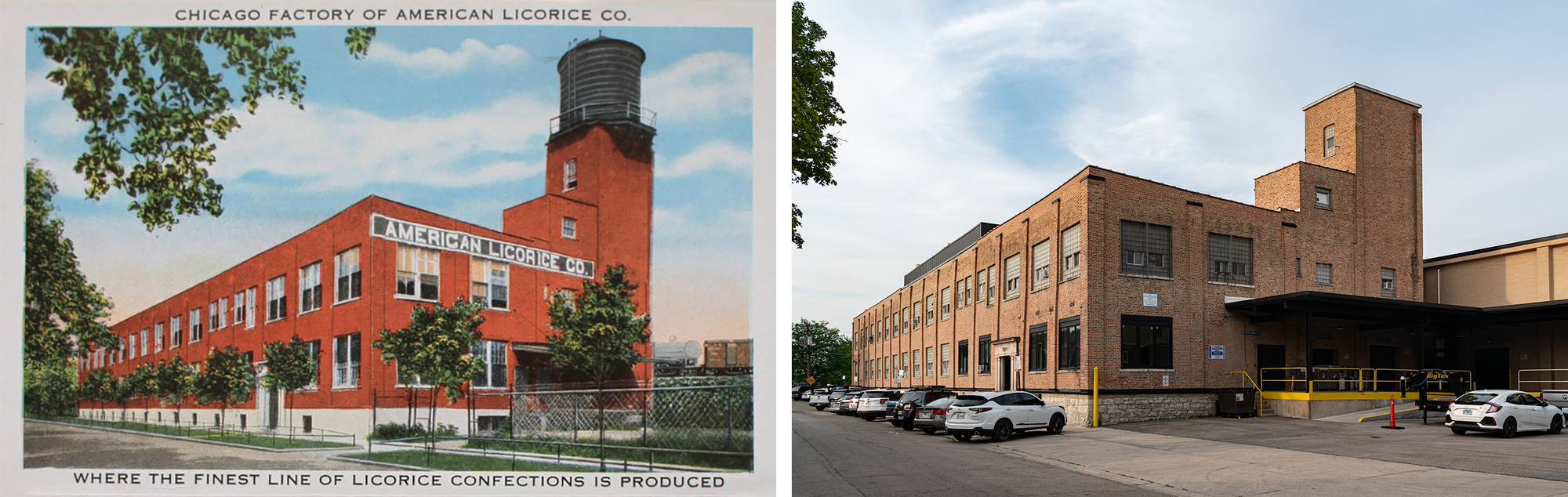

Chicagoland was (is?) the candy manufacturing capital of the US, but these pre-war factories have range—this one also pumped out munitions, shade cloth, steel springs, and lava lamps over the last 115 years. Completed in 1909 and designed by architect Niels Buck, for more than 50 years American Licorice Company cooked, cut, dried, and packaged licorice here, giving this corner of Hermosa a uniquely sweet smellscape. The makers of Red Vines, Super Rope, and Sour Punch moved out in the early 1980s—depriving the neighborhood of a top-notch trick-or-treating stop—and today the building is home to small studios, design agencies, and a vintage shop.

So, what’s changed?

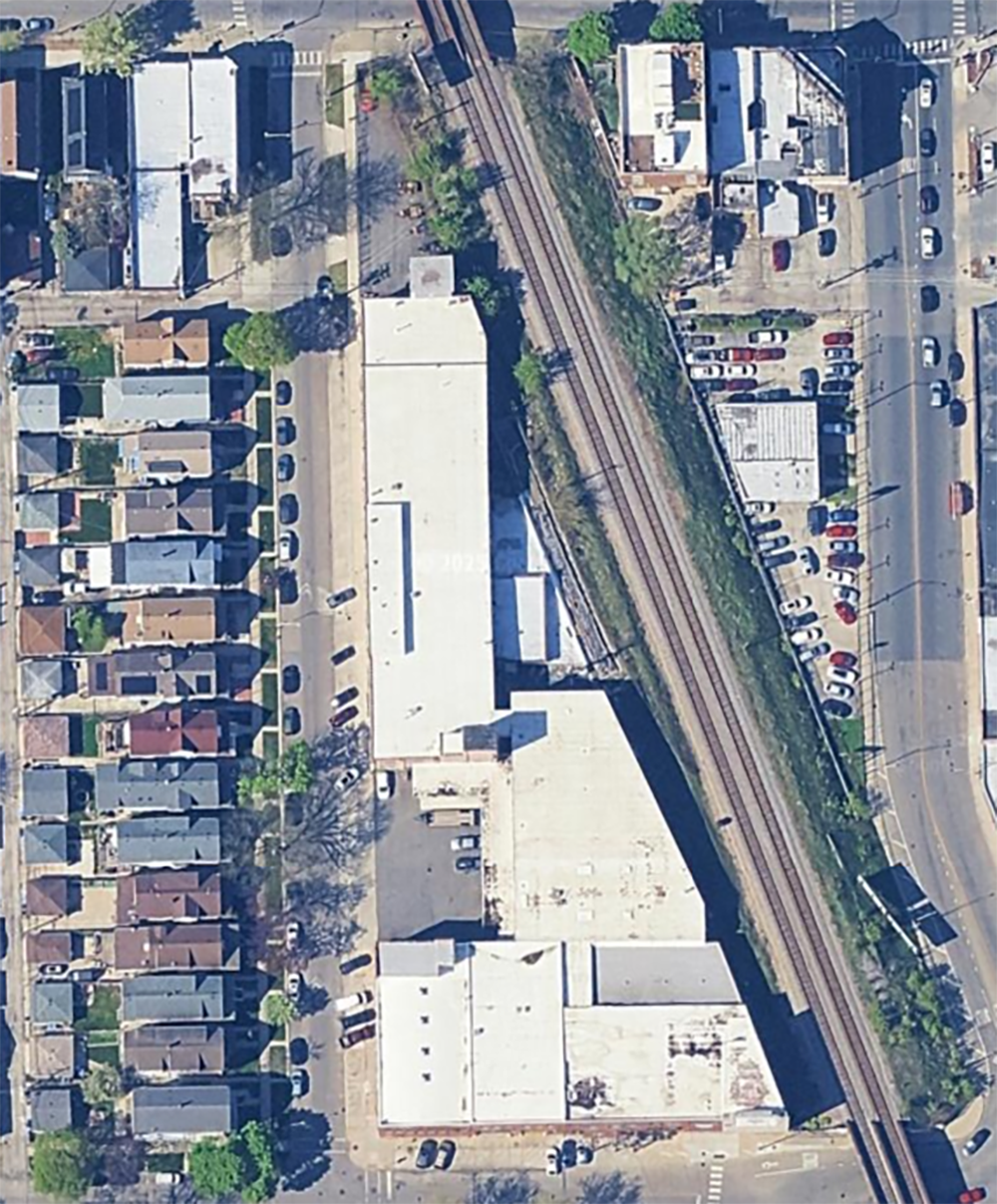

- A mid-century addition added a building to the southeast, eventually fusing the two distinct factories on this block into one big connected facility.

- Most of the windows were replaced with glass blocks—a more secure and better insulated window treatment in an environment of disinvestment or during an energy crisis.

- The water tank was removed—one of the thousand that have disappeared from Chicago’s skyline over the last half century.

- Ripping up the parkway and its street trees to make room for diagonal car parking was a particularly petty way to make this block just a little worse.

Still though—it’s recognizably the same building and in use for light production work after 115+ years, even after the removal of the railroad siding that once brought materials for manufacturing directly to the factory. Not a bad run.

1909 building permit | March 1910 building permit | February 1910 fire | 1910-1911 photo, Logan Square Preservation | 2025 photo

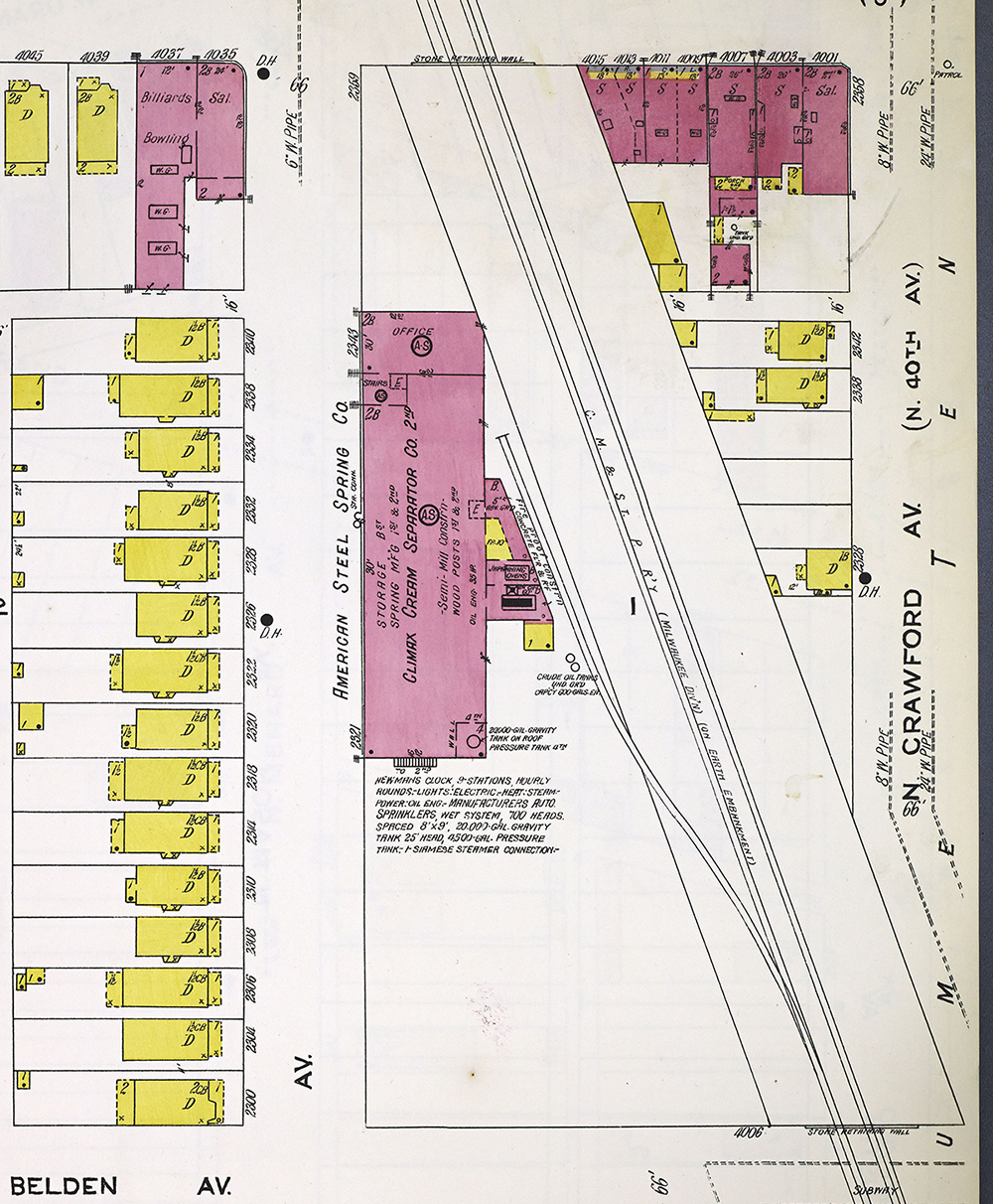

Industrialist Gustav J. Heimann developed this lot in 1909, building a single-story factory on 40th Court, present-day Keystone Ave. Designed by Danish-born Chicago architect and developer Niels Buck, the site had direct access to the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway’s Milwaukee Division tracks. This was a slightly odd commission for Buck’s firm, which specialized in single-family homes on the north side—particularly mass-produced residential.

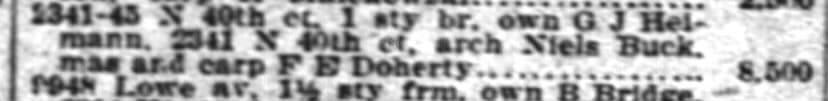

The first tenant was the National Shade Cloth Co., but the building burned in a fire soon after it was completed. With the northwest side of Chicago booming and the damaged building in need of renovation anyway, Buck’s firm was rehired to repair and expand the factory in 1910. By 1912 the shade cloth manufacturer was on its way out, the factory for sale or for lease, and Illinois Spring & Wire moved in. They went bankrupt in 1914, and the American Steel Spring Co. and Climax Cream Separator and Manufacturing Company, a dairy machinery manufacturer, ended up sharing the building in the late 1910s.

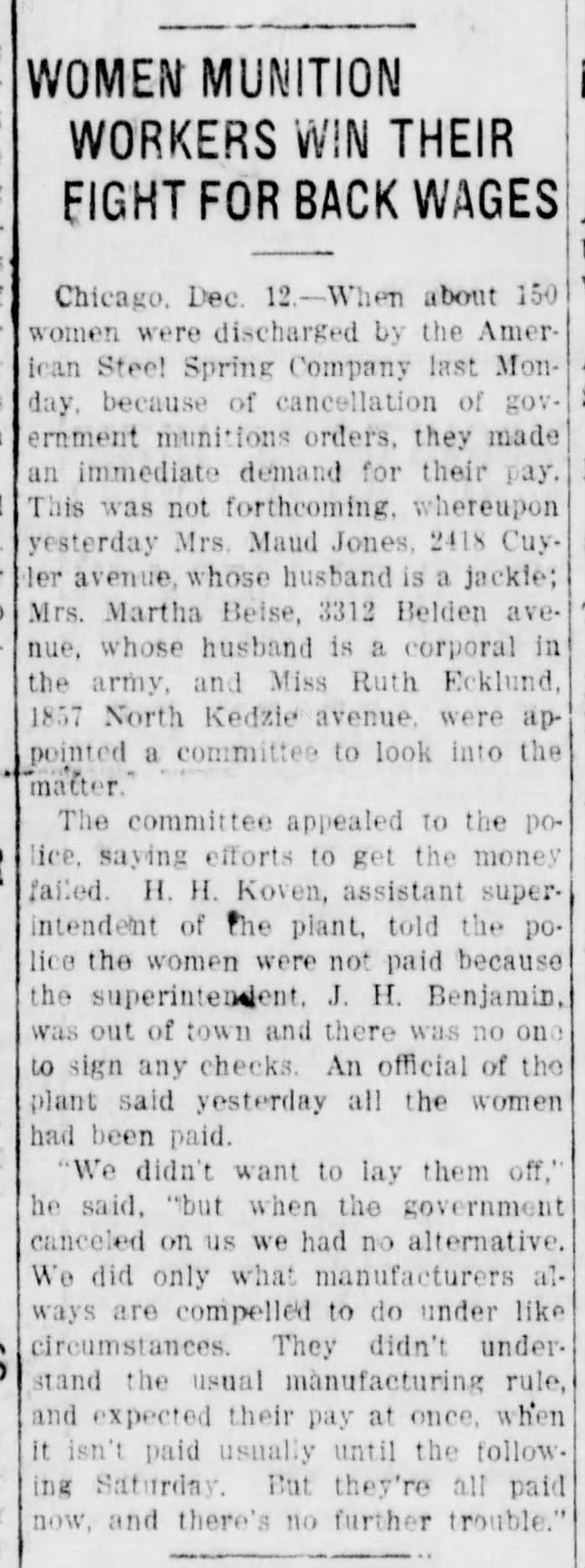

1911 National Shade Cloth salesmen wanted ad | 1912, opportunity to purchase or lease the factory | 1914, Illinois Spring bankrupt | 1915, Illinois Spring looking for co-tenants | 1916, Climax Manufacturing help wanted ad | | 1918 help wanted ads for American Steel Spring Co. | 1918, women munition workers fight for back wages

Federal government spending drives private sector growth, and after the US entered World War I, the steel spring manufacturer snagged a contract to manufacture munitions and expanded rapidly. They hired hundreds of women to fill factory positions in inspection and bench work…and then—less than a year later—fired them all once the fighting stopped and the government canceled the company’s procurement contract. Still flush with profits from federal spending, American Steel Spring bought a larger facility at Walnut and Sangamon near the river and moved out.

1918 - 2024

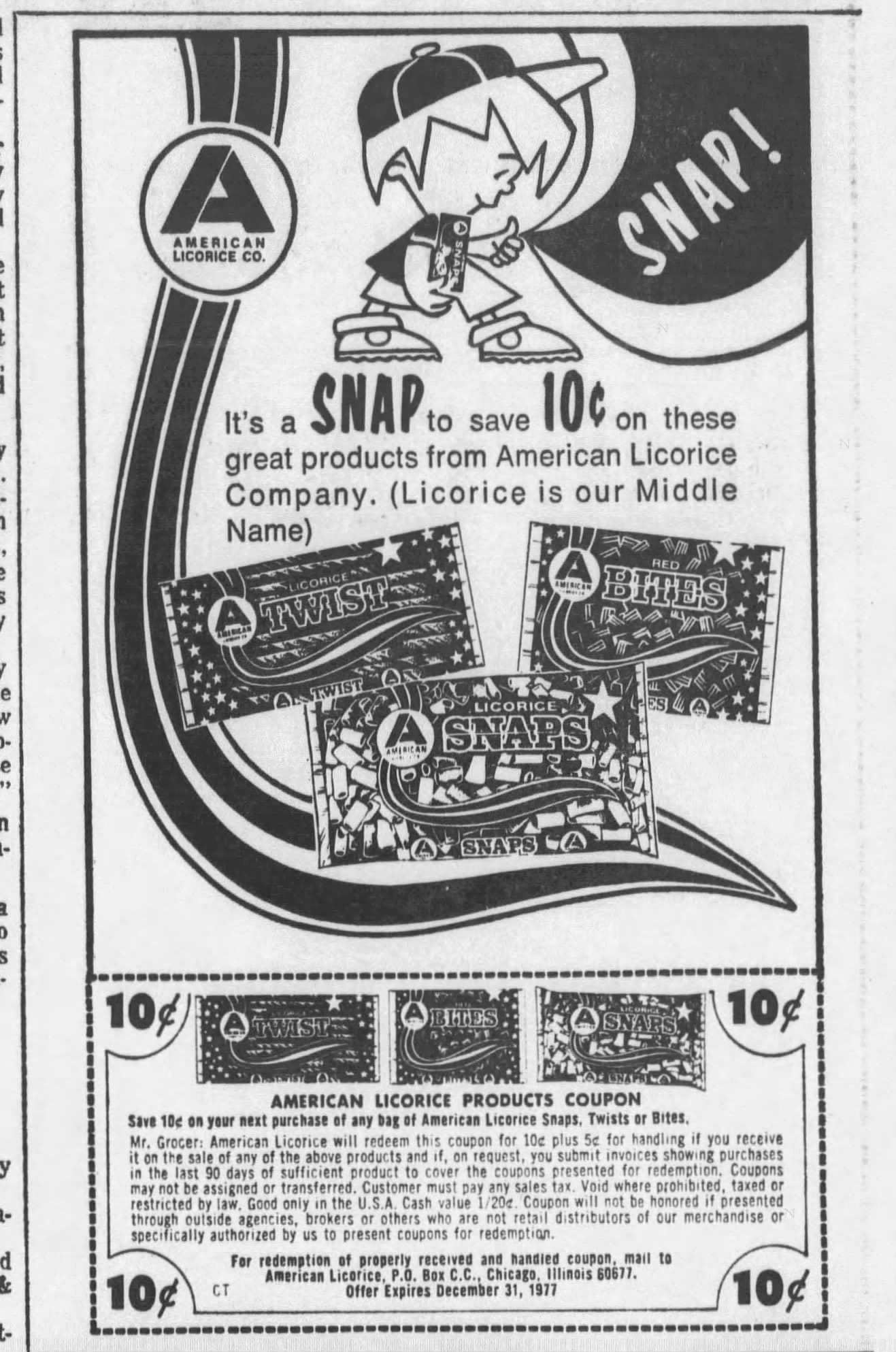

The American Licorice Company—established on Chicago’s West Side in 1914 by an unsuccessful chocolatier, Martin Kretchmer, who found black licorice a sweeter gig—took over the factory around 1920. At one point, Chicago companies produced more than 30% of the candy manufactured in the United States, an industry built on rail access, ingredients from Midwestern agriculture (corn syrup, corn starch, and dairy products), and agglomeration effects. American Licorice Co. grew into a successful cog in the city’s confectionery manufacturing cluster, which once employed more than 25,000 people. While the company—which still exists as an independent, family-owned candymaker based in Indiana—is best known for Red Vines, this plant produced black licorice twists, snaps, and bits (the company didn’t develop Red Vines until the 1950s, manufacturing them in California).

American Licorice Co. expanded the factory twice in the 1950s and 1960s—together with the Bresler’s Ice Cream factory just to the south, manufacturing facilities would eventually fill the entire block. It looks like the building lost its railroad siding around that time, presumably in connection with one of those expansions.

1922, 1948, and 1952 help wanted ads | 1965 expansion | 1968 help wanted ad | 1977 ad

After building a modern new plant in Union City, California in the late 1960s to replace their San Francisco operation, the American Licorice Co. looked at their aging factory on Keystone Ave and decided to repeat the trick—they acquired a more modern facility in Alsip, Illinois. Production started there in 1976, but American Licorice Co. kept this building open until 1982 as things ramped up in the suburbs.

From the late 1980s to the early 1990s, the building—by this point a complex of three contiguous buildings—was home to Lava-Simplex Internationale, the first US manufacturer of lava lamps (by that point it was a division of Haggerty Enterprises). The company, which acquired the exclusive US rights to make lava lamps from its British inventors in 1965, produced their Lava Lite lamps at three other Chicago locations (1735 N. Ashland, 1650 W. Irving Park, and 4041 S. Emerald) before they landed here.

Eazypower, a screwdriver tip and power tool accessory company, bought the complex in 1999. Headquartered here for more than twenty years, they sold the building in 2021 and moved to Skokie.

2025 photos

Production Files

Further reading:

- "WHAT’S BLACK (OR RED) AND YUMMY? IT’S A SECRET" in the Chicago Tribune in 1994

- Property flyer from when the building was on sale in 2021

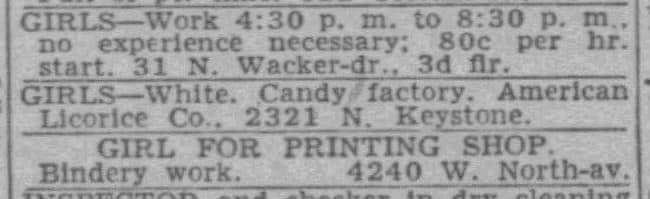

From what I could tell, this wasn't a common requirement in the licorice maker's help wanted ads, but still—a dark reminder of how normalized racist discrimination was (and is) in American workplaces.

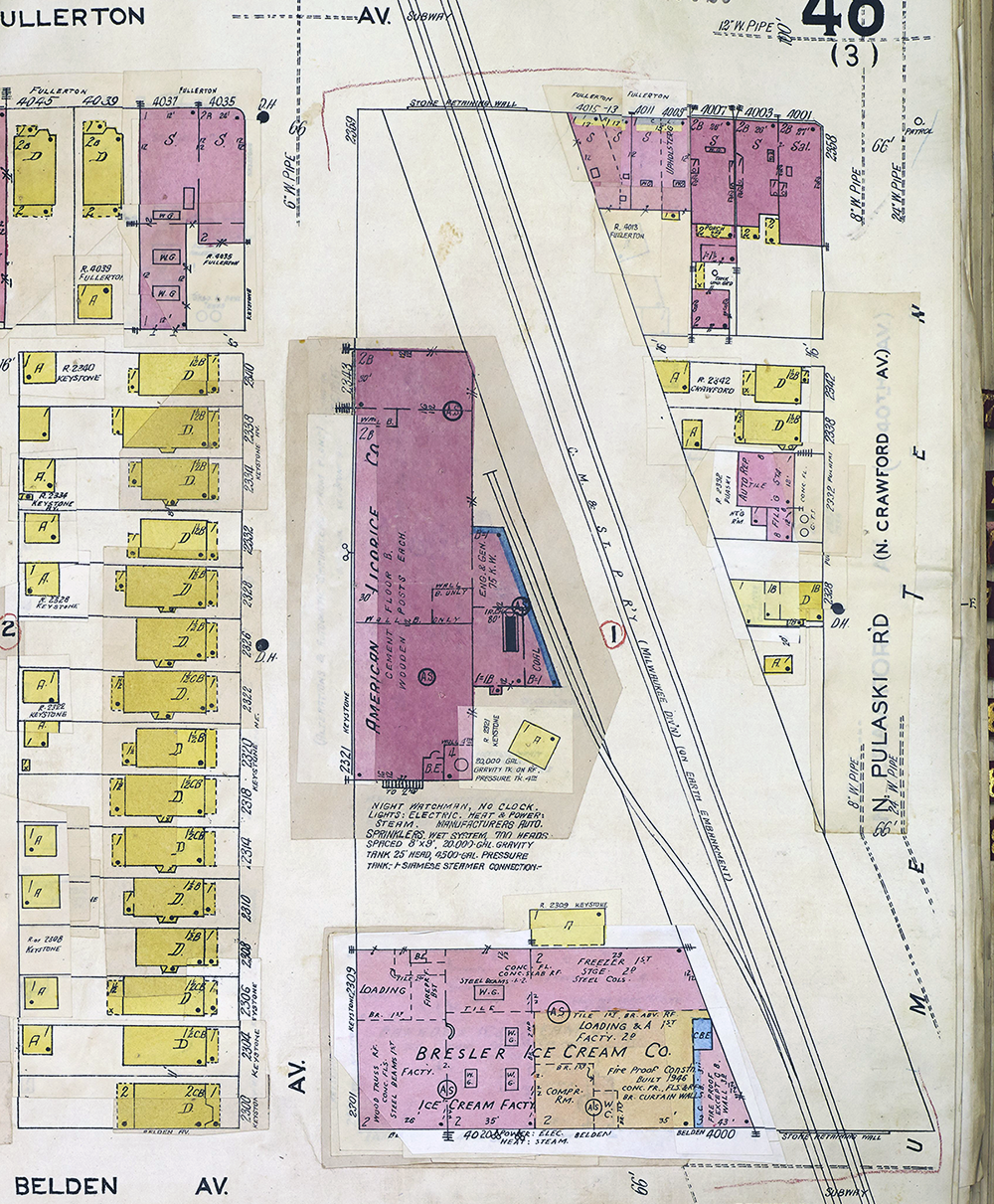

1918 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map | 1938 aerial, Illinois State Geological Survey | 1951 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map | 1970, 1980, 1990 aerials, Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning | 2024 Google Earth

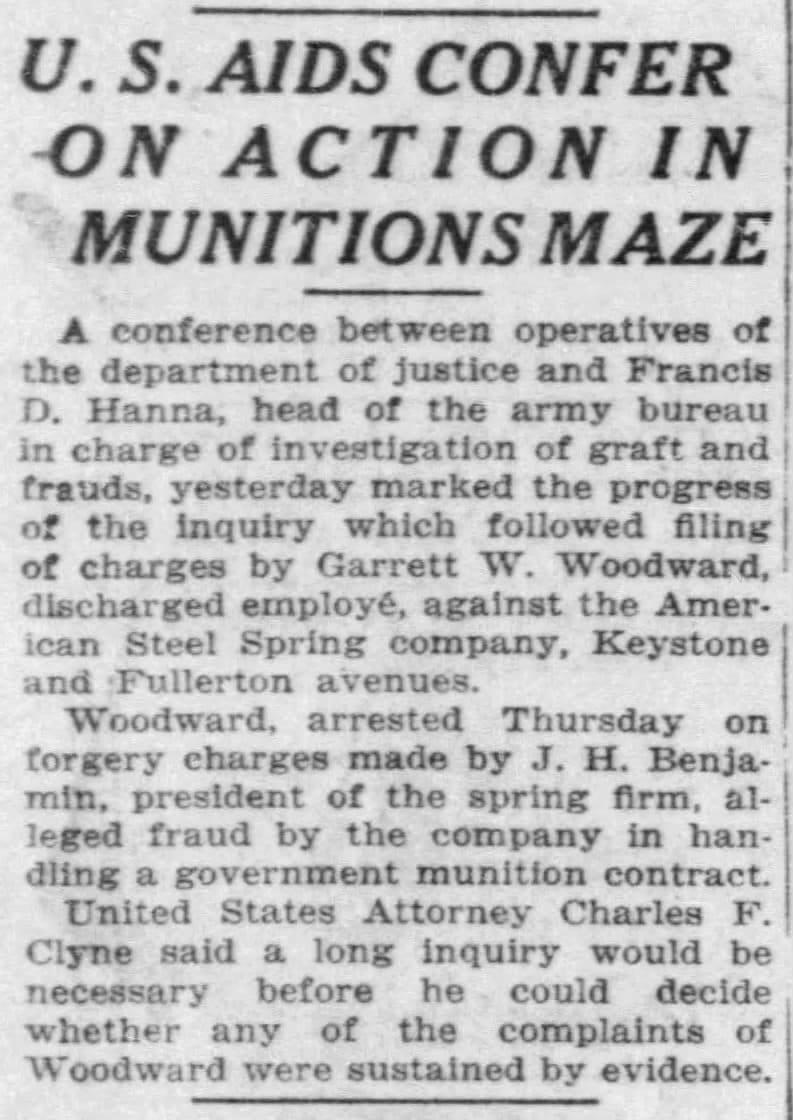

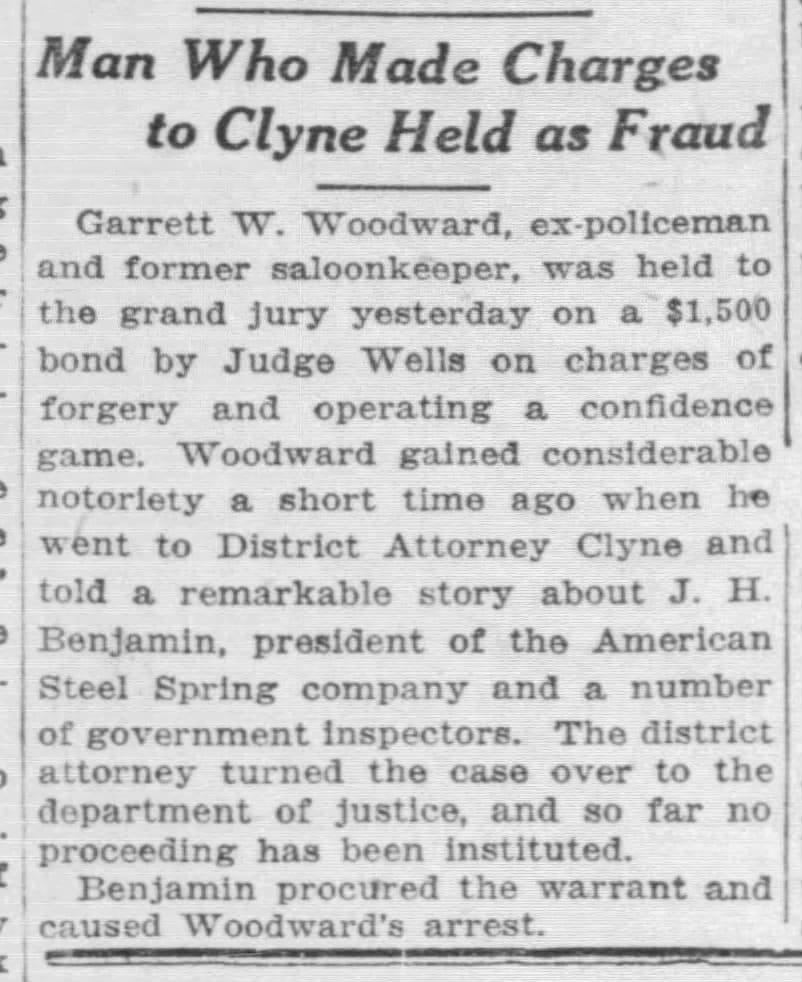

There was a kerfuffle about potential fraud in their federal munitions manufacturing contract.

1919 articles about a potential contracting fraud case

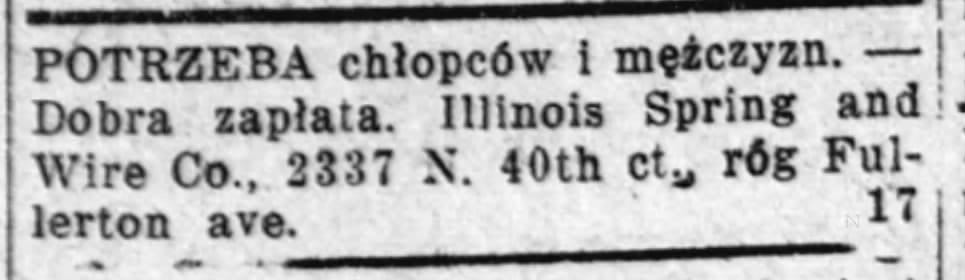

Gotta find your workforce where they're at, and the manufacturers based here regularly advertised in Polish-language media.

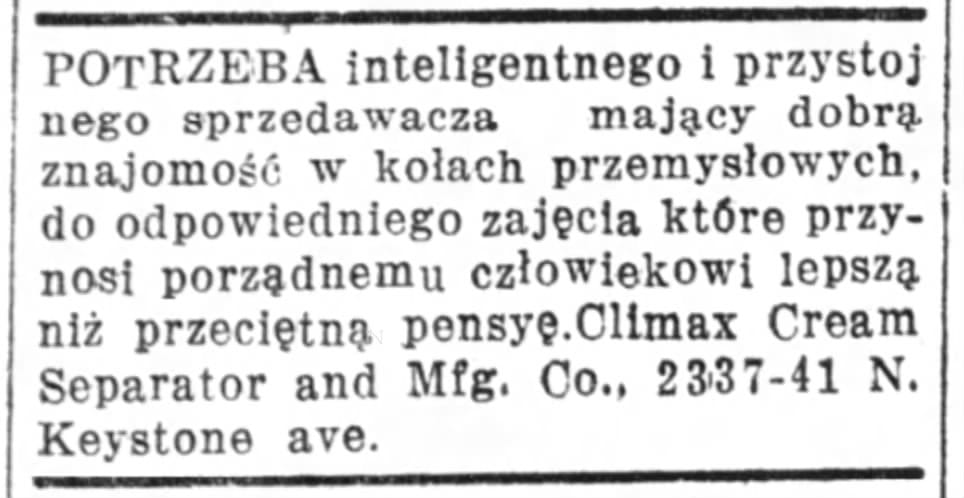

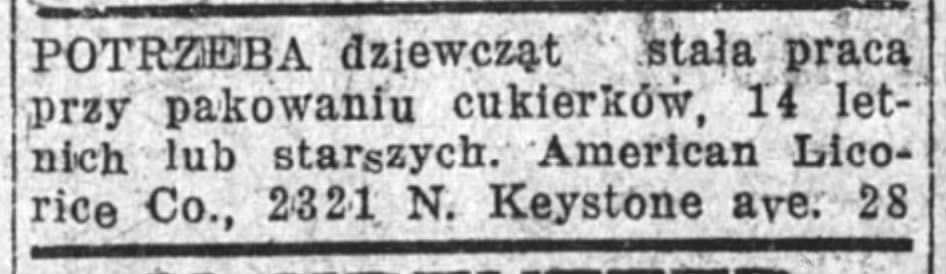

1912, 1917, and 1922 Polish-language help wanted ads for jobs in the building, Dziennik Chicagoski

The building's location near the Healy Metra stop is a strength—you can literally see it from the platform.

Where I took the photo from.

Member discussion: