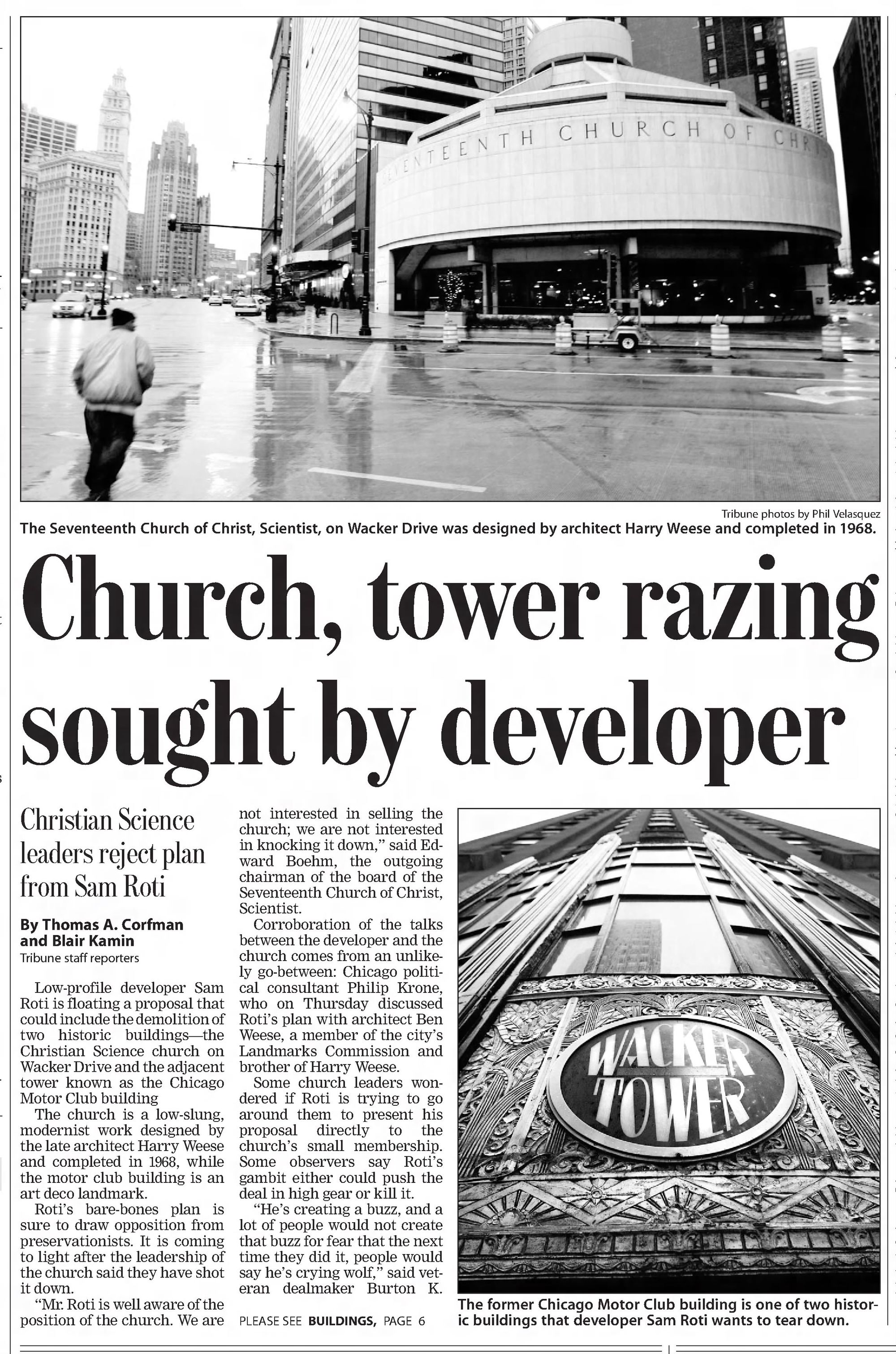

Chicago has filled in around it (...and the hotel next door filled in its balconies), but Harry Weese’s modernist Seventeenth Church of Christ Scientist, wedged into an oddly-shaped little lot, still looks as simultaneously ancient and futuristic as the day it opened in 1968.

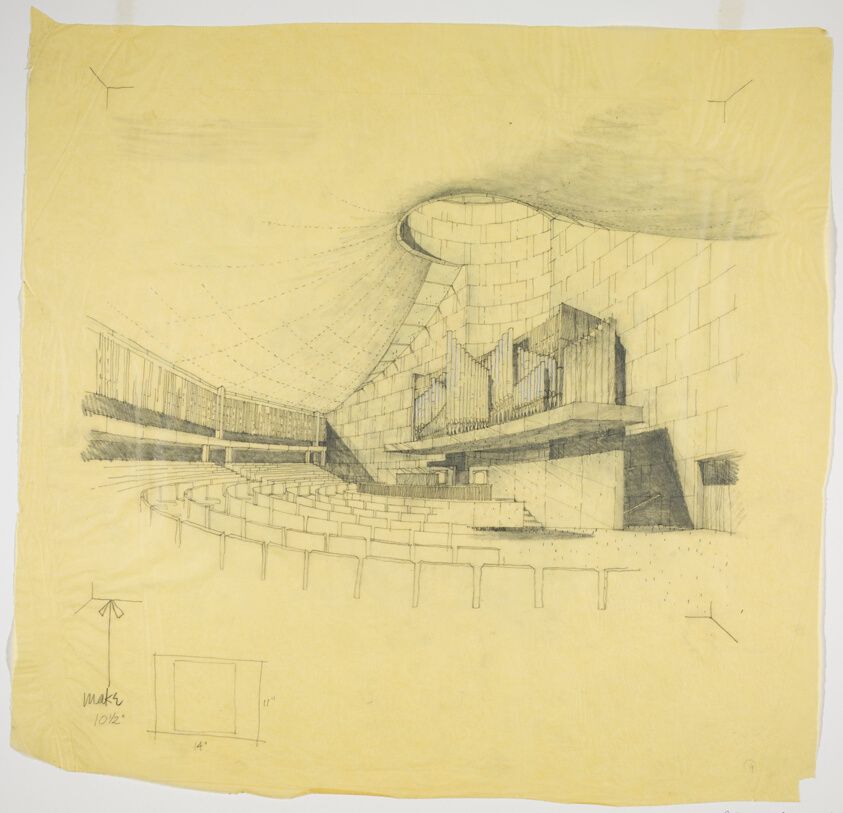

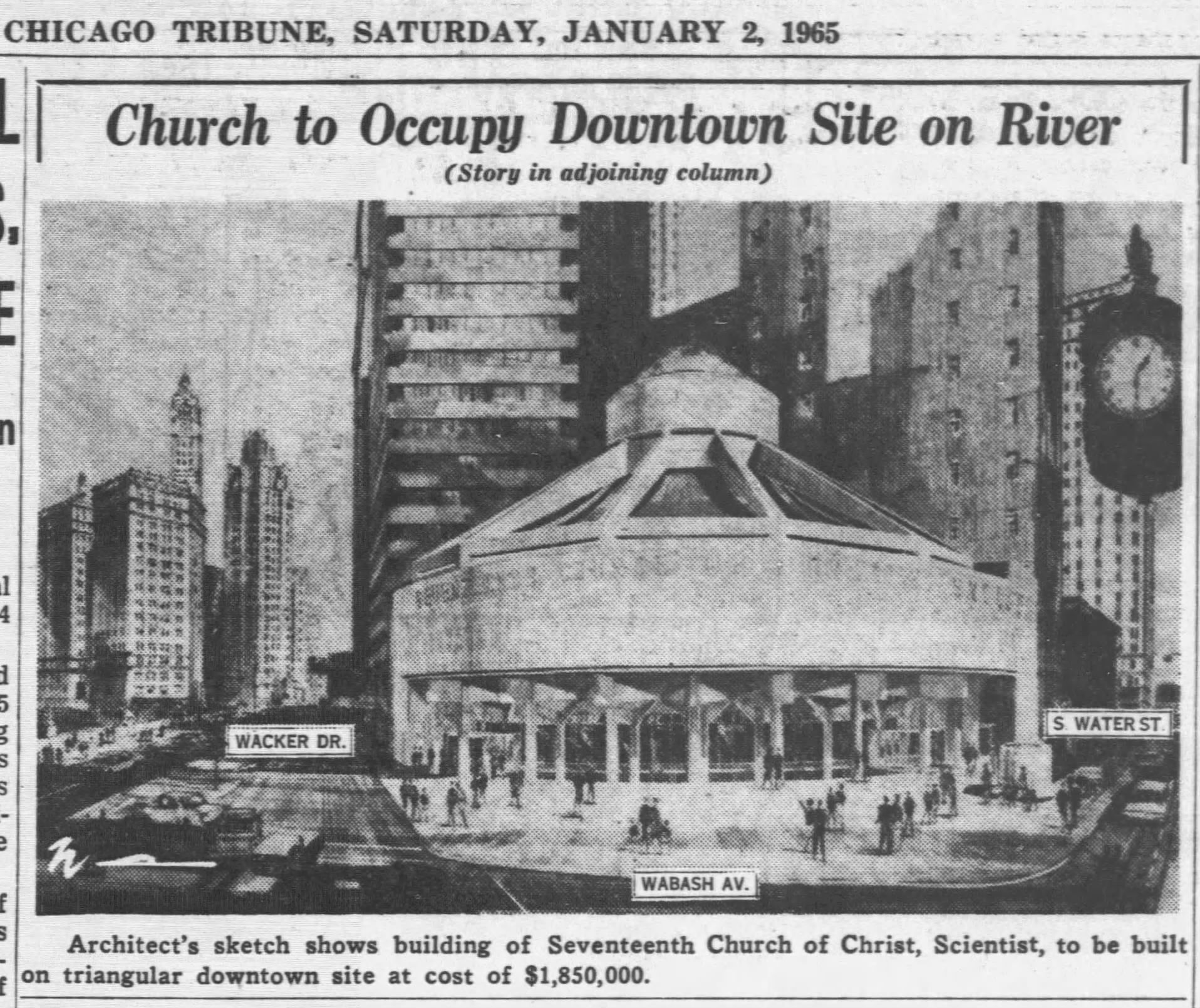

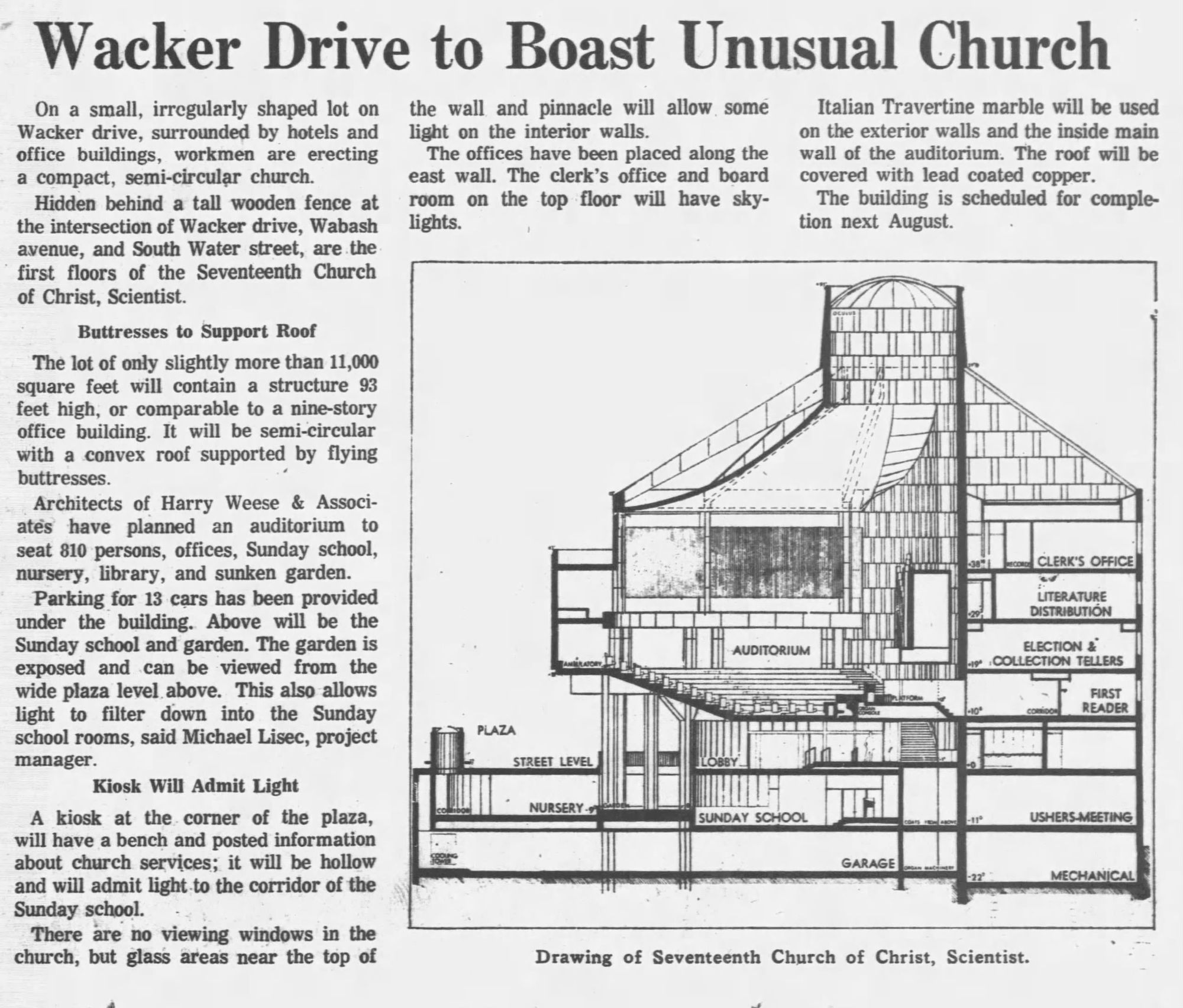

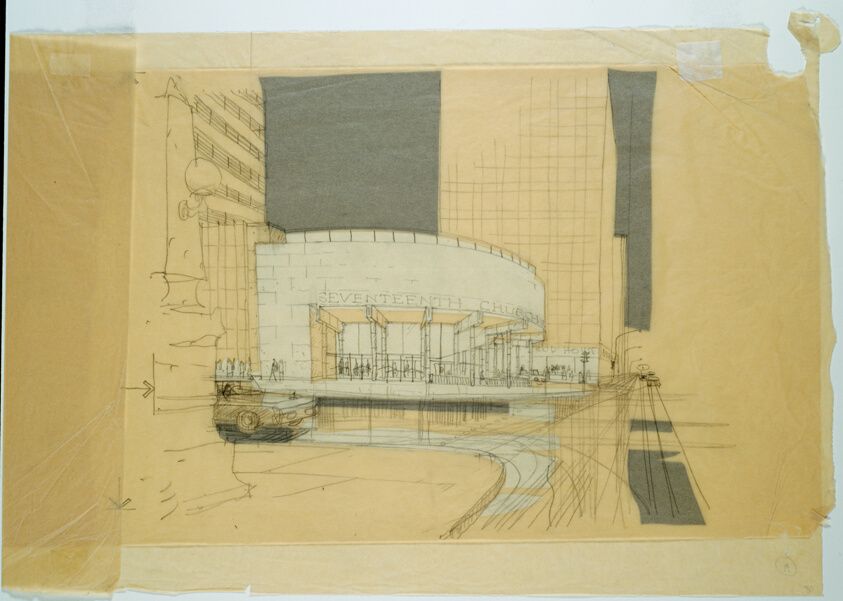

The church’s geometric monumentality reflects a modernist take on a classical amphitheater, with a hint of Brutalism–some raw concrete, yeah, but the facade is clad with travertine. The building’s unique shape stems from the constraints of the site, but is also a direct expression of the main interior space, a windowless semi-circular amphitheater lit with natural light from an oculus skylight.

Providing a diverse array of spaces—childcare and Sunday school rooms, church offices, a reading room, etc.—was a challenge for Weese & Associates. One much-heralded solution was a sunken garden, which enabled natural light to reach the subterranean nursery and Sunday school room (the sunken garden itself is a little sad and scruffy-looking, tbh—not great light for plants).

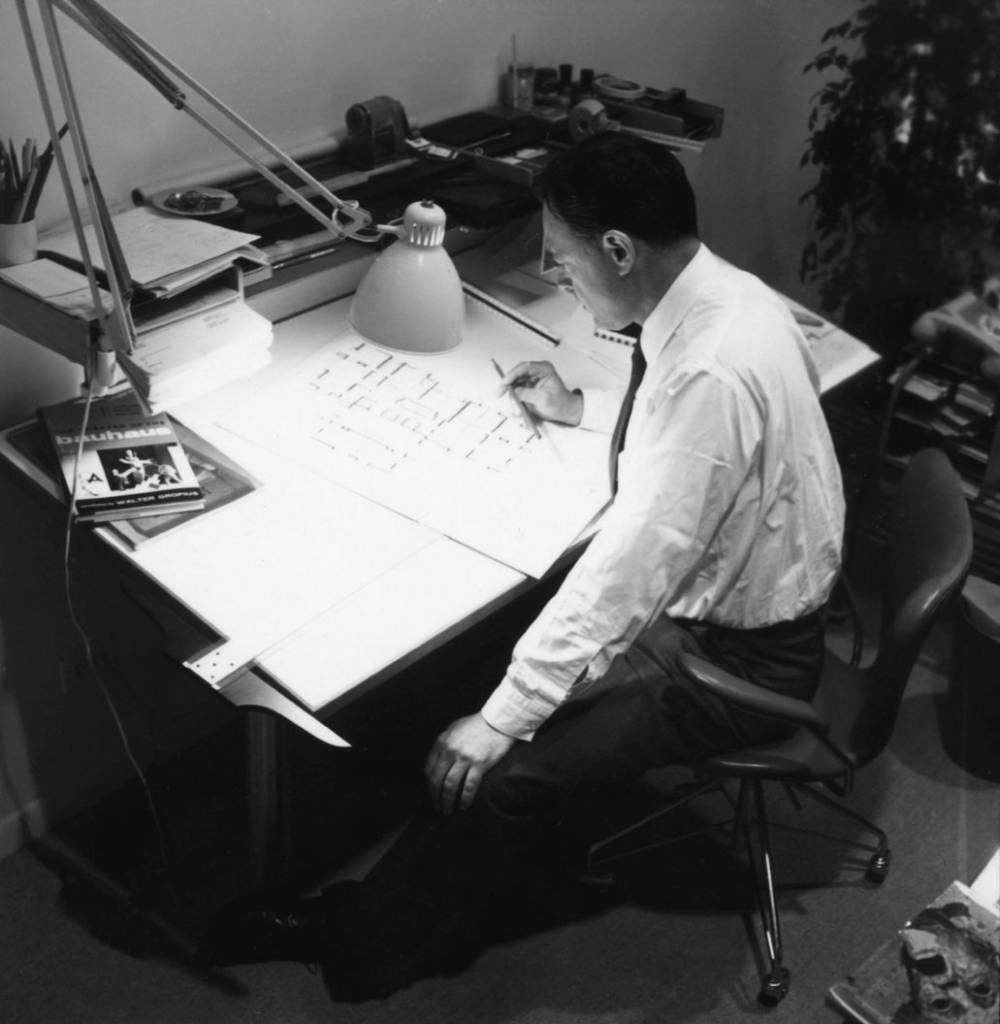

Weese was a fascinating architect. An unMiesian modernist and, later, a proto-postmodernist, he was an early preservationist and adaptive reuse pioneer, and a progressive urbanist during a time when white flight and highways were killing US cities. Weese tapped into a wealthy social network from his childhood on Chicago’s North Shore and his time at Cranbrook Academy to build his architecture practice. By the time he was chosen to design the Seventeenth Church, Weese’s career was at its peak, part of a five-year stretch when his firm also worked on the Washington Metro, the First Baptist Church in Columbus (IN), and the Time-Life Building in Chicago, as well as the restoration of Adler & Sullivan’s Auditorium Building. Alcoholism and personal misbehavior marred his later life and career, and the critical legacy of Weese’s work is probably hurt by its variety—like his classmate, Eero Saarinen, it’s so diverse that it defies categorization into a broader movement.

…but here Weese was really cooking.

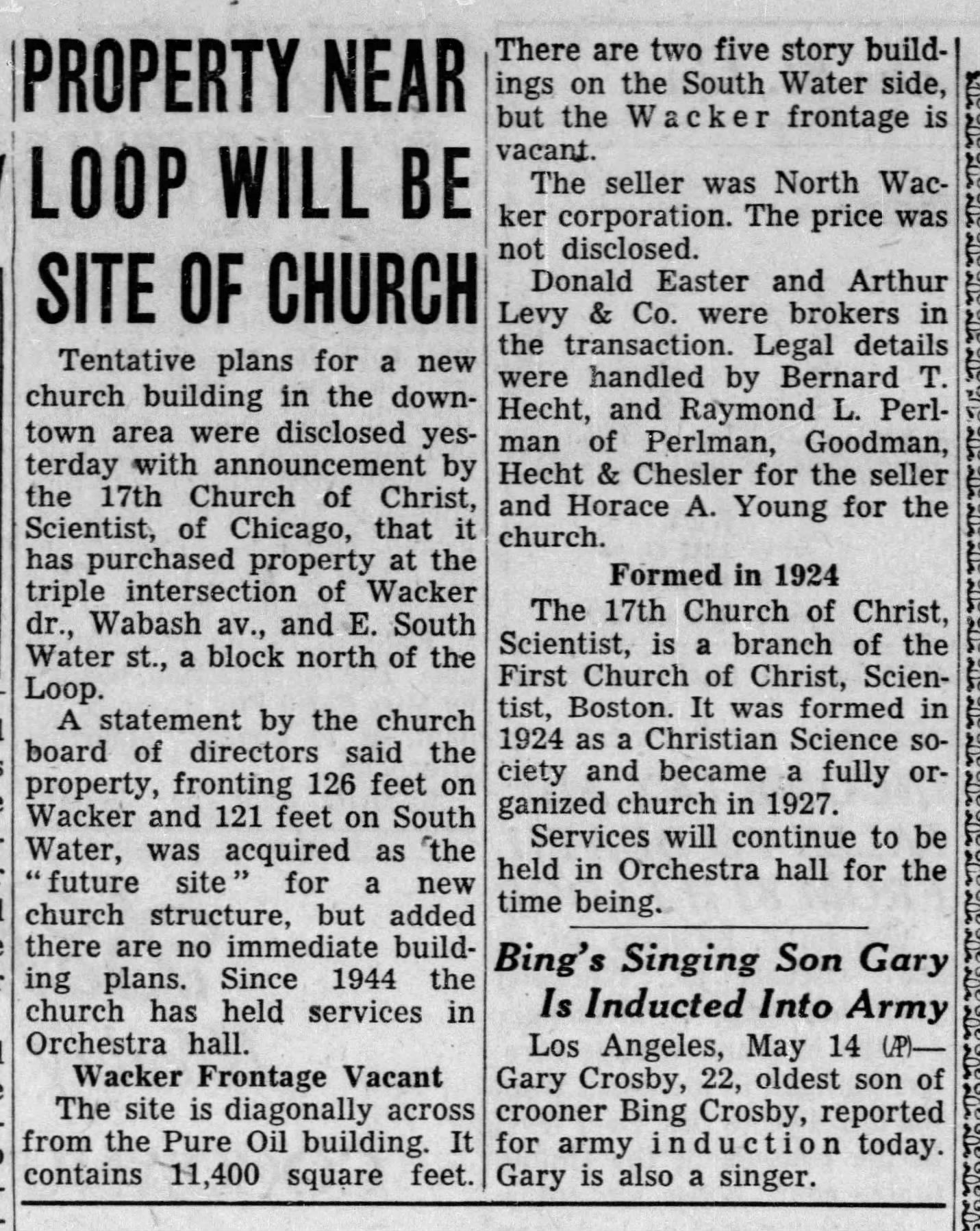

Established in 1924, Chicago’s Seventeenth Church of Christ Scientist rented out various venues for their first 40 years, including space at the New Masonic Temple Building (which today holds the Nederlander Theatre) and Orchestra Hall. Finally ready to settle down, the Seventeenth Church bought this lot in 1956. They considered 34 architects before selecting Weese. Some articles say Frank Lloyd Wright was considered, but his career was winding down by the time they bought this site and he'd been dead for four years when Weese was selected—I'm skeptical. Weese himself said that his main competition here was fellow Chicagoan Walter Netsch (which, that would’ve been interesting too). Not at all religious, when asked about his own religion by the congregation here Weese told them, “My father was Episcopalian, my mother Presbyterian, and I’m an architect.” Buoyed by their success here, Weese & Associates competed to design the Christian Science Center in Boston, the denomination’s mother church, but lost to I.M. Pei.

By the time the Seventeenth Church opened in 1968, the number of Christian Scientists was in decline. However, the Seventeenth Church has survived even as the denomination has shrunk from 17 congregations in the city to five.

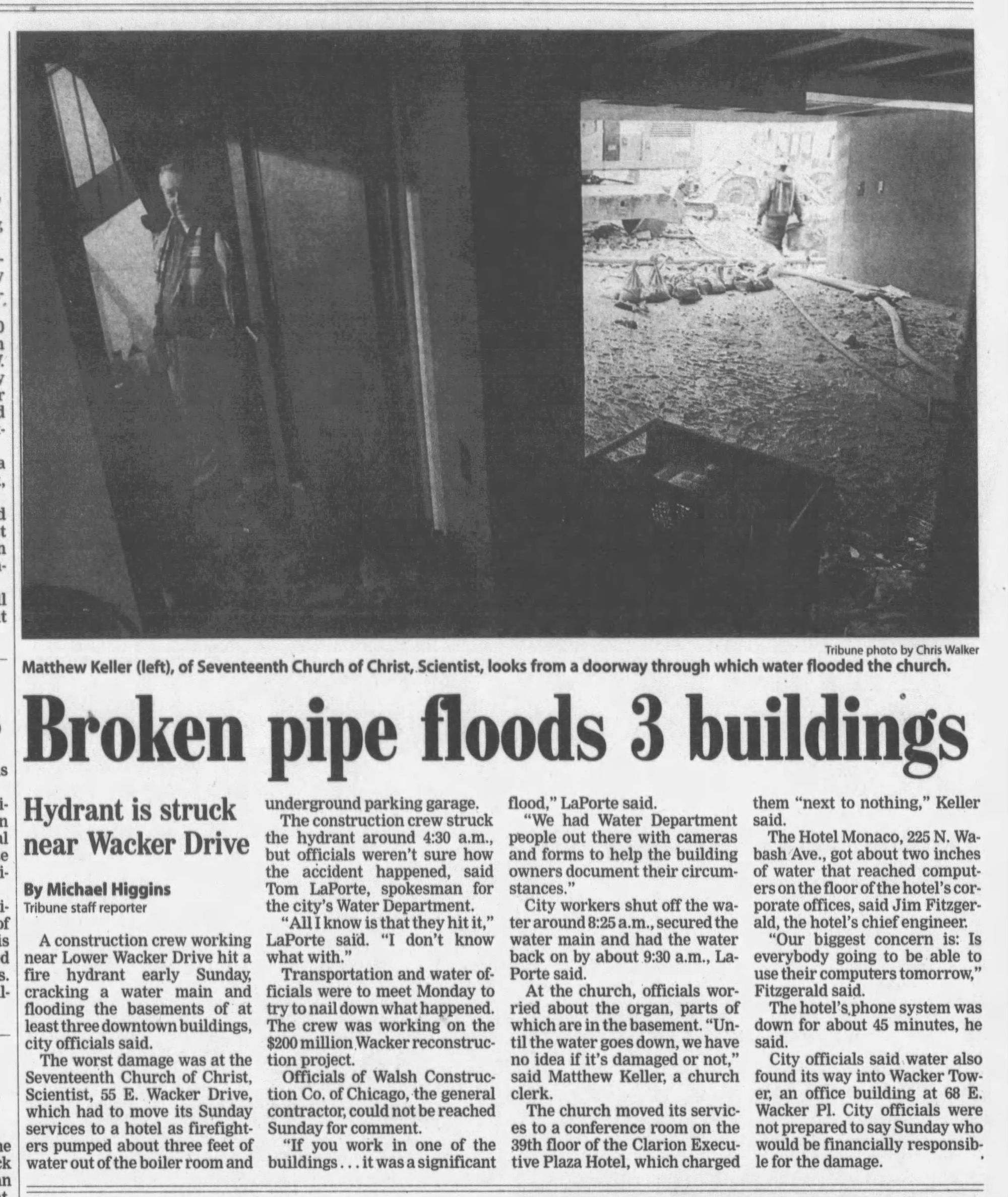

Developer Sam Roti floated a plan in the mid-2000s to buy the church and its neighbors and demolish them for a high-rise, a proposal made public potentially as a pressure tactic by the developer—the congregation had no interest in the idea. It remains a rare single-purpose Loop church today, occasionally open to the public for events like Open House Chicago or used for civic events like ward meetings.

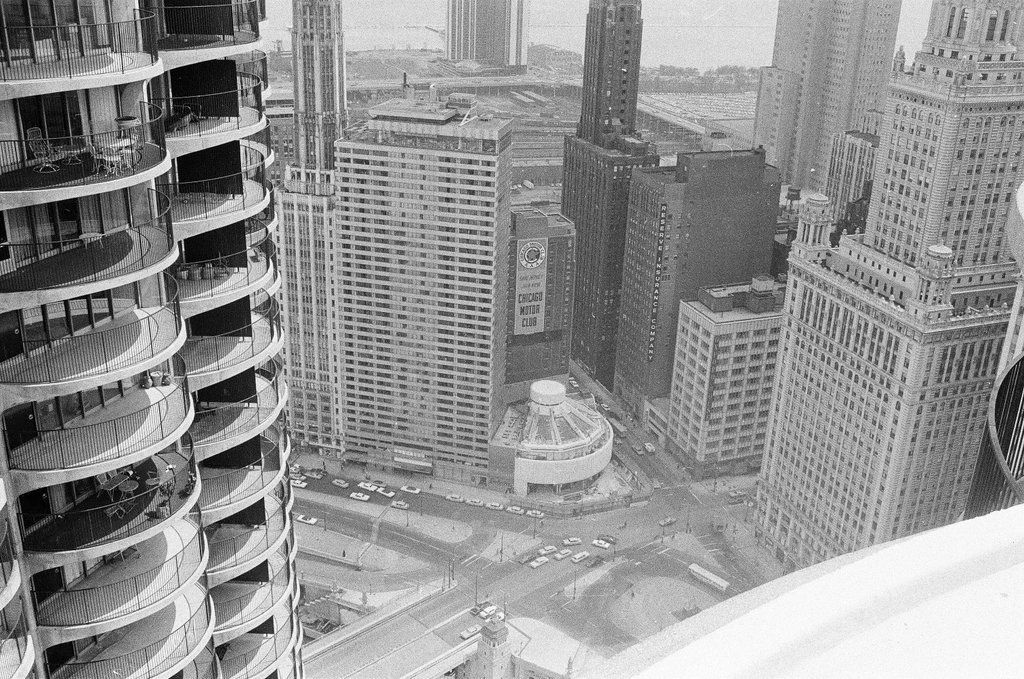

Behind the Seventeenth Church in the postcard is the Chicago Motor Club Building. A really lovely bit of Art Deco built in 1929 and designed by Holabird & Root, it’s still there, but was converted into a hotel in the mid-2010s.

That “JOIN NOW CHICAGO MOTOR CLUB” sign is long since painted over, but it wouldn’t be visible anyway—the gray pixelated facade is the Hilton Garden Inn, built in 2015 on the tiny lot in between the church and the Motor Club Building and designed by GREC Architects. With the hotel rooms oriented towards the north and south elevations of the building (...partially because the developer didn't want to buy the church's air rights to guarantee their west-facing view), instead of windows they clad the western elevation in a metal mosaic vaguely inspired by the Chicago River, an abstract representation of sunlight reflecting on water.

To the left of the church is Milton Schwartz’s criminally underrated Executive House Hotel, which looks remarkably contemporary for a building completed in 1960. I had no idea it once had open balconies, which in Schwartz’s telling gave the facade texture. The balconies, which make more sense when you learn that it was originally planned as an apartment building, were enclosed during a 1980s renovation. Milton Schwartz’s initial proposal for this site called for a circular apartment building, but they pivoted to a more traditional, bank-friendly rectangle to get financing—Schwartz must've been a little annoyed that Weese’s round church was built next door and Marina City went up across the river only a few years later.

Production Files

Further reading:

- The Society of Architectural Historians entry

- In the Christian Scientists own words

- The Harry Weese interview from the Chicago Architects Oral History Project

- Good article in WBEZ on the 17th Church

- Fascinating, sad article on Weese's life and career in Chicago Mag

- Excellent analyis of Weese's oeuvre in Places Journal

- On the gray pixelated facade of the Hilton Garden Inn

- Some nice photos of the church and the Hilton on GREC Architects' website

Member discussion: